Abstract

Background/Objectives

Vegans and to a lesser extent vegetarians have low average circulating concentrations of vitamin B12; however, the relation between factors such as age or time on these diets and vitamin B12 concentrations is not clear. The objectives were to investigate differences in serum vitamin B12 and folate concentrations between omnivores, vegetarians and vegans and to ascertain whether vitamin B12 concentrations differed by age and time on the diet.

Subjects/Methods

A cross-sectional analysis involving 689 men (226 omnivores, 231 vegetarians and 232 vegans) from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Oxford cohort.

Results

Mean serum vitamin B12 was highest among omnivores (281, 95% CI: 270-292 pmol/l), intermediate in vegetarians (182, 95% CI: 175-189 pmol/l), and lowest in vegans (122, 95% CI: 117-127 pmol/l). Fifty-two percent of vegans, 7% of vegetarians and one omnivore were classified as vitamin B12 deficient (defined as serum vitamin B12 < 118 pmol/l). There was no significant association between age or duration of adherence to a vegetarian or a vegan diet and serum vitamin B12. In contrast, folate concentrations were highest among vegans, intermediate in vegetarians, and lowest in omnivores, but only two men (both omnivores) were categorised as folate deficient (defined as serum folate < 6.3 nmol/l).

Conclusion

Vegans have lower vitamin B12 concentrations, but higher folate concentrations, than vegetarians and omnivores. Half of the vegans were categorised as vitamin B12 deficient and would be expected to have a higher risk of developing clinical symptoms related to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Keywords: vitamin B12, folate, vegetarian, vegan

Introduction

While individuals who consume vegetarian or vegan diets may have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (Key et al., 1999, Key et al., 2009), there may also be a greater risk of developing nutritional deficiencies, owing to the exclusion from the diet of meat and fish in vegetarians, and all animal products in vegans. Vitamin B12 is naturally present only in foods of animal origin, and vegans who do not consume sufficient quantities of foods fortified with vitamin B12 such as some breakfast cereals, plant-based milks, soy products and yeast extract, or regularly take a vitamin B12 supplement, will have an increased risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency.

Results from previous studies have shown that vegans have lower average serum concentrations of vitamin B12 in comparison to omnivores and vegetarians (Herrmann et al., 2003, Krajčovičová-Kudláčková et al., 2000, Majchrzak et al., 2006), with evidence from some (Herrmann et al., 2003, Hokin & Butler, 1999, Hung et al., 2002, Krajčovičová-Kudláčková et al., 2000, Mann et al., 1999), but not all (Haddad et al., 1999, Herrmann et al., 2001, Majchrzak et al., 2006,) studies suggesting that serum vitamin B12 concentrations are also lower in vegetarians compared to omnivores. Several reports also indicate that a considerable proportion vegans (Haddad et al., 1999, Waldmann et al., 2004) and vegetarians (Herrmann et al., 2003, Koebnick et al., 2004) have circulating concentrations of vitamin B12 indicative of depleted stores (serum vitamin B12 < 150 pmol/l). Previous research in populations consuming a mixed diet suggests that, on average, serum vitamin B12 concentrations are lower in older individuals (Baik & Russell, 1999); however, few studies have assessed this in older vegetarians and vegans. Moreover, it is not clear to what extent the length of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet is associated with serum concentrations of vitamin B12.

The objective of the present study was to compare the serum vitamin B12 and folate concentrations and dietary intake of these micronutrients in British men consuming an omnivorous, vegetarian or vegan diet and to assess the associations of age and duration of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet with serum concentrations of vitamin B12.

Methods

Study population

The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Oxford cohort study recruited more than 65 000 participants between 1993 and 1999. Full details of the recruitment methods and the study participants have been described elsewhere (Davey et al., 2003). The protocol for the EPIC-Oxford study was approved by the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Clinical Research Ethics Committee, the Central Oxford Research Ethics Committee and local research ethics committees, and all participants gave written informed consent.

This study population sample consists of 689 men who provided a blood sample at recruitment to the EPIC-Oxford cohort between 1994 and 1997 and who had no history of cancer. In order to maximise the heterogeneity of dietary exposure, approximately equal numbers of men with different dietary habits were selected with no matching criteria; omnivores who reported consuming 3 or more servings of meat per week, lacto-ovo vegetarians who reported consuming soya-milk and/or soya products and vegans. There were 226 omnivores, 231 vegetarians, and 232 vegans included in these analyses. The ethnicity of 96% of the study sample was white and the other 4% were Bangladeshi or Chinese.

Omnivores were defined as people reporting meat consumption. Vegetarians were defined as people who reported consuming dairy products (including milk, cheese, butter, and yogurt) and eggs (including eggs in cakes and other baked foods) but no meat or fish. The majority of vegetarians were lacto-ovo vegetarians (88%), consuming both dairy products and eggs, with smaller proportions avoiding eggs (8%) or dairy products (4%). Vegans were defined on the basis that they did not consume any foods of animal origin (meat, fish, dairy products or eggs). The duration of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet was calculated as the age at recruitment minus the age at which the respondent last ate meat or fish, or any of meat, fish, dairy products or eggs, respectively.

Assessment of dietary and lifestyle variables

All participants completed a validated semi-quantitative 130-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) at baseline (Bingham et al., 1994, Bingham et al., 1995). Regular use of a vitamin supplement over the past 12 months was assessed in the FFQ and based on the detailed information of the type used, participants were categorised on the basis that they regularly used a vitamin B12 supplement or not and whether they regularly used a folate supplement or not. The daily intakes of vitamin B12 and folate obtained from supplements were also calculated. The 12 men who did not provide any information on the use of vitamin B12 or folate supplements were categorised as non-users for each of these variables.

Participants self-reported their height and weight and Quetelet’s body mass index (BMI; weight (kg)/height (m2)) was calculated. Participants were further characterised by their smoking status (“never”, “former”, “current”) and level of education (“some secondary school”; “higher secondary school”, “university degree or equivalent”).

Laboratory methods

Following recruitment, blood was collected at local general practice surgeries into 10-mL Safety-Monovettes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). The samples were sent by post in sealed containers at ambient temperature to the EPIC laboratories in Norfolk where they were centrifuged and aliquots were stored in liquid nitrogen (−196°C) until analysis. Concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate in serum were measured with the use of a Quantaphase II B12/Folate Radioassay (Bio-Rad, CA) at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, King’s College Hospital, London. The inter-batch coefficients of variation (CV) for vitamin B12 was 7.9% and for folate it was 7.7%. Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 less than 118 pmol/l and serum folate concentrations less than 6.3 nmol/l were used as cut-points to categorise deficiency as used in United Kingdom National Diet and Nutrition Survey (Ruston et al., 2004).

Follow-up data

In 2001, the vegan men who had a serum vitamin B12 measurement were contacted and asked to provide another blood sample. Out of the 227 surviving vegan men contacted, 65 (29%) had another blood sample collected. Full blood counts were made on a Sysmex cell counter (Sysmex UK Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK), serum vitamin B12, serum holotranscobalamin (holoTC), plasma methylmalonic acid (MMA) and plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) were measured as described in detail elsewhere (Lloyd-Wright et al., 2003).

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software (release 9; Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX). Where necessary, the dietary variables and serum vitamin B12 and folate concentrations were log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution. To assess the effect of duration of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet on serum vitamin B12 concentrations, vegetarians and vegans were divided into four categories (< 5, 6-10, 11-15, ≥ 16 y) according to the time they had been on these diets. The geometric mean and 95% CI for serum B12 were calculated for 9 diet-duration groups (omnivores, 4 groups of vegetarians and 4 groups of vegans) by using multiple linear regression. Categories of BMI (< 22.5, 22.5-24.9, ≥ 25 kg/m2), use of a vitamin B12 supplement, smoking status, level of education, number of days the blood sample spent in the post (1, 2 or ≥ 3 d) and alcohol consumption (quartiles) were included as covariates but only BMI, education and supplement use were included in the final model. Similar analyses were performed to investigate the associations of age and education with serum vitamin B12 concentrations. P values for trend for the association between time of adherence to the diet and age with serum concentrations of vitamin B12 were assessed separately for each diet group by treating age and duration on the diet as continuous variables in the regression models. All tests were two-tailed and differences were regarded as statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 47 y; omnivores were on average 7 y older than vegetarians and 10 y older than vegans (Table 1). Vegans had the lowest mean BMI and a greater proportion of omnivores were categorised as having some secondary school level of education compared to vegetarians and vegans. The median time that vegetarian men had adhered to their diet was 11 years and for vegan men it was 7 years. Among the omnivores, 4% regularly took a supplement containing vitamin B12 compared to 19% of both vegetarians and vegans.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the EPIC-Oxford men by diet group

| Omnivores n = 226 |

Vegetarians n = 231 |

Vegans n = 232 |

P 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) [mean (s.d.)] | 52.8 (10.7) | 46.2 (11.7) | 42.8 (13.1) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) [mean (s.d.)] | 26.1 (3.7) | 23.4 (3.0) | 22.7 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20-39 | 15 (7) | 75 (32) | 104 (45) | < 0·001 |

| 40-49 | 85 (38) | 79 (34) | 64 (28) | |

| 50-59 | 55 (24) | 40 (17) | 31 (13) | |

| 60-78 | 71 (31) | 37 (16) | 33 (14) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 22.5 | 37 (16) | 93 (40) | 125 (54) | |

| 22.5-24·9 | 58 (26) | 87 (38) | 70 (30) | < 0·001 |

| ≤ 25·0 | 131 (58) | 51 (22) | 37 (16) | |

| Education | ||||

| Some secondary school | 54 (24) | 35 (15) | 32 (14) | |

| Higher secondary school | 71 (31) | 69 (30) | 82 (35) | 0·023 |

| University degree or equivalent | 101 (45) | 127 (55) | 118 (51) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 109 (48) | 121 (52) | 139 (60) | |

| Former | 80 (35) | 90 (39) | 70 (30) | 0·015 |

| Current | 37 (16) | 20 (9) | 23 (10) | |

| Vitamin B12 supplement users | ||||

| Yes | 10 (4) | 45 (19) | 43 (19) | < 0.001 |

| No | 216 (96) | 186 (81) | 189 (81) | |

| Time on vegetarian or vegan diet (y)2 | ||||

| ≤ 5 | - | 54 (23) | 89 (38) | |

| 6-10 | - | 56 (24) | 69 (30) | |

| 11-15 | - | 44 (19) | 44 (19) | |

| ≥ 16 | - | 74 (32) | 29 (13) |

Abbreviations: EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Values are n (%), except where indicated otherwise.

Differences in means for continuous variables were assessed using ANOVA and differences in proportions were assessed by using a chi-square test.

Time on a vegetarian and vegan diet was available for 228 and 231 vegetarians and vegans, respectively.

The mean intake of dietary vitamin B12 among omnivores not taking a vitamin B12 supplement was 8.8 μg, which was almost five times greater than the mean intake in vegetarians (P < 0.001) and 36 times higher than the mean intake in vegans (P < 0.001, Table 2). Only 3% of the vegan men not taking a vitamin B12 supplement reported a dietary intake of vitamin B12 above the UK RNI of 1.5 μg/day compared to 31% of the vegetarians and all omnivores. Among vitamin B12 supplement users, 89% of vegetarians and 63% of vegans met the RNI for vitamin B12 intake. Vegans not taking a folic acid supplement had a significantly higher intake of folate than both vegetarians (P = 0.001) and omnivores (P < 0.001) and the mean intake of folate in the vegetarians was higher than in the omnivores (P = 0.014). Dietary intake of folate was above the RNI (200 μg/day) in 96% of the omnivores, 99% of the vegetarians and 98% of the vegans. All supplement users had an intake of folate (from diet and supplements) that was above the RNI.

Table 2.

Estimated daily intake among omnivores, vegetarians and vegans1

| Omnivores (n = 226) |

Vegetarians (n = 231) |

Vegans (n = 232) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 intake (μg/day) [mean (95% CI)] | |||

| Non-supplement users | 8.76 (7.93 - 9.68)a | 1.92 (1.72 - 2.13)b | 0.24 (0.21 - 0.26)c |

| Supplement users2 | 11.06 (6.21 - 19.67)a | 3.39 (2.58 - 4.46)b | 3.17 (2.39 - 4.20)b |

| Folate intake (μg/day) [mean (95% CI)] | |||

| Non-supplement users | 342 (329 - 357)a | 369 (353 - 386)b | 420 (402 - 438)c |

| Supplement users | 595 (513 - 690) | 610 (566 - 658) | 611 (564 - 663) |

| Total energy intake (MJ) | 10.6 (2.7) | 9.2 (2.5) | 8.5 (2.6) |

| Carbohydrate (% total energy) | 43.6 (5.9) | 51.5 (6.4) | 53.4 (7.8) |

| Fat (% total energy) | 34.0 (5.3) | 31.0 (5.7) | 29.9 (7.4) |

| Protein (% total energy) | 16.5 (2.7) | 13.2 (2.0) | 12.7 (1.9) |

Values are mean (s.d.) except where indicated otherwise.

Differences in the means between the diet groups were tested for by using ANOVA.

Includes intake from diet and supplements.

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.05

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.05

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.05

The mean serum vitamin B12 in vegans was 33% lower than in vegetarians and 57% lower than in omnivores, and was 35% lower in vegetarians compared to omnivores (Table 3). Fifty-two percent of vegans and 7% of vegetarians had vitamin B12 concentrations below the cut-point for biochemical deficiency (< 118 pmol/l). A further 21%, 17% and 1% of vegans, vegetarians and omnivores, respectively, had a serum vitamin B12 indicative of depletion (118 to 150 pmol/l). There was no significant difference in mean serum concentration of vitamin B12 between men who reported taking a vitamin B12 supplement compared to non-users of supplements in any of the diet groups (results not shown).

Table 3.

Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate according to diet group

| Omnivores (n = 226) |

Vegetarians (n = 231) |

Vegans (n = 232) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Vitamin B12 (pmol/l) [mean (95% CI)] | 281 (270 - 292)1a | 182 (175 - 189)b | 122 (117 - 127)c |

| “Deficient” < 118 pmol/l | 1 (0) | 16 (7) | 121 (52) |

| “Depleted” 118 to 149 pmol/l | 3 (1) | 40 (17) | 48 (21) |

| “Sufficient” ≥ 150 pmol/l | 222 (98) | 175 (76) | 63 (27) |

| Serum Folate (nmol/l) [mean (95% CI)] | 20·0 (19·1 - 21·0)a | 28·0 (26·7 - 29·4)b | 37·5 (35·8 - 39·3)c |

| “Deficient” < 6·3 nmol/l | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| “Sufficient” ≥ 6.3 nmol/l | 224 (99) | 231 (100) | 232 (100) |

Values are n (%), except where indicated otherwise

Differences in the means between the diet groups were tested for by using ANOVA.

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.001

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.001

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences, P < 0.001

The mean concentration of serum folate in vegans was 34% higher than in vegetarians and 88% higher than in omnivores (Table 3). Very few men (< 1% of omnivores) were categorised with biochemical folate deficiency (< 6.3 nmol/l). Vegetarians who reported taking a folate supplement had significantly higher mean serum folate concentration compared to non-supplement users (P = 0.015) but mean serum folate concentrations between supplement and non-supplement users did not differ for omnivores (P = 0.738) or vegans (P = 0.072, results not shown).

Among participants not taking a supplement, dietary intake of vitamin B12 was significantly correlated with serum vitamin B12 concentrations (Spearman’s ρ = 0.72, P < 0.001). The correlation between dietary folate intake and serum concentrations of folate was weaker but statistically significant (ρ = 0.12, P = 0.002).

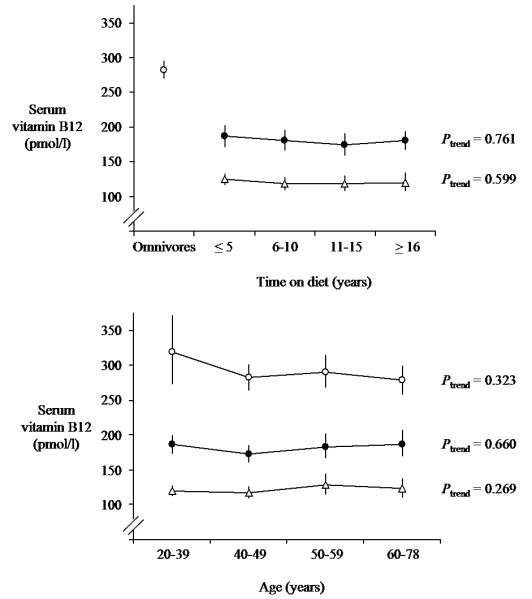

The adjusted mean concentrations of serum vitamin B12 by time of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet and by age are shown in Figure 1. There was no significant association between the length of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet and serum vitamin B12 concentrations. There was also no significant association between age or education and serum concentrations of vitamin B12 in any diet group (results for education not shown). All results were similar when restricted to non-users of vitamin B12 supplements (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Mean serum concentrations of vitamin B12 in omnivores (n = 226), vegetarians (n = 231) and vegans (n = 232) by duration of adherence to a vegetarian or a vegan diet (top panel) and age (bottom panel). The results in the figure show the geometric mean and 95% CI adjusted for BMI, level of education and use of a vitamin B12 supplement, by diet group (○, omnivores; ●, vegetarians; and Δ, vegans). P values for trend by duration of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet and age within each diet group were obtained by treating the number of years since becoming vegetarian or vegan and age as continuous variables in the regression analyses, respectively.

Of the 65 vegan men with repeat measures of serum vitamin B12 taken approximately 6 years later, 34% were considered biochemically vitamin B12 deficient (serum vitamin B12 < 118 pmol/l) and 8% were categorised as deplete (118 to 150 pmol/l) (Table 4). There was a strong positive association between serum vitamin B12 concentration and holoTC (r = 0.77, P < 0.0001) and an inverse association with MMA and tHcy (r = −0.74 and r = −0.73, respectively; P < 0.0001 for both). Among the 22 men who had serum vitamin B12 concentrations below 118 pmol/l, 82% had concentrations of holoTC that would indicate vitamin B12 deficiency (< 35 pmol/l) but only 32% had a combination of a MMA greater than 0.75 μmol/l and tHcy greater than 15 μmol/l that would identify men who were likely to have a vitamin B12 deficiency.

Table 4.

Mean (95% CI) concentrations of selected biochemical measurements according to categories of serum vitamin B12 concentrations in 65 vegan men with follow-up data.

| < 118 pmol/L n = 22 |

118-149 pmol/L n = 5 |

≥ 150 pmol/L n = 38 |

P 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum vitamin B12 (pmol/l) | 51 (40 - 64) | 131 (81 - 213) | 302 (253 - 360) | |

| HoloTCII (pmol/l) | 26.0 (20.8 - 32.6) | 29.7 (18.6 - 47.6) | 77.3 (65.1 - 91.6) | < 0.001 |

| HoloTCII < 35 pmol/l (%) | 82 | 60 | 13 | |

| MMA (μmol/l) | 0.68 (0.52 - 0.89) | 0.45 (0.26 - 0.79) | 0.18 (0.15 - 0.22) | < 0.001 |

| tHcy (μmol/l) | 26.0 (21.2 - 31.8) | 15.9 (10.4 - 24.2) | 10.8 (9.3 - 12.6) | < 0.001 |

| MMA > 0.75 μmol/l and tHcy > 15 μmol/l (%) | 32 | 40 | 3 |

Abbreviations: HoloTCII, holotranscobalamin II; MMA, methylmalonic acid; tHcy, total homocysteine

Differences in the means between the categories of serum vitamin B12 were tested for by using ANOVA

Discussion

The results from this study show that mean serum concentrations of vitamin B12 reflected the level of intake of meat and animal products; omnivores had the highest concentrations of serum vitamin B12 and vegans the lowest. In addition, over half of men consuming a vegan diet and 7% of men consuming a vegetarian diet were categorised – according to their serum vitamin B12 concentrations – as being vitamin B12 deficient. Very few men were categorised as being folate deficient (only two omnivores).

The finding that vegans have lower serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and a greater prevalence of biochemical vitamin B12 deficiency than both omnivores and vegetarians is in agreement with results from several other studies (Krajčovičová-Kudláčková et al., 2000, Majchrzak et al., 2006, Obeid et al., 2002). However, the results from some but not all studies have shown that vegetarians have lower vitamin B12 concentrations compared to omnivores and a greater proportion of vegetarians had serum vitamin B12 concentrations indicative of deficient or depleted stores (Haddad et al., 1999, Herrmann et al., 2001, Herrmann et al., 2003, Hokin & Butler, 1999, Hung et al., 2002, Krajčovičová-Kudláčková et al., 2000, Majchrzak et al., 2006, Mann et al., 1999). The results from this study do not support the idea that vegetarians, because they consume some animal products, are not at risk of developing a vitamin B12 deficiency (Herbert, 1994).

These results showed no evidence that serum vitamin B12 concentrations decreased with increasing duration on a vegetarian or vegan diet among non-supplement users, which is in agreement with results from one other small study (Rauma et al., 1995) but not with another where an inverse correlation between serum vitamin B12 concentrations and time on a vegan diet (r = −0.18, p = 0.047) was reported (Waldmann et al., 2004). Evidence from an intervention study suggests that when the intake of vitamin B12 is restricted, serum concentrations of vitamin B12 may decline much more rapidly than previously believed. In 13 lacto-ovo vegetarians, mean serum vitamin B12 concentrations were reduced from 345 pmol/l to 226 pmol/l within two months of consuming a vegan diet (Crane et al., 1994). Only two men in this study had recently started consuming a vegan diet (< 1 year) and therefore, the effect on vitamin B12 concentrations of a short term dietary change could not be assessed. It is possible that once vitamin B12 stores decline to a certain level, serum concentrations are maintained despite a very low intake over a prolonged period via a number of mechanisms that might include an increased absorption of vitamin B12 in the gut, reduced vitamin B12 excretion, and an increased capacity to absorb recycled vitamin B12 from the bile via the enterohepatic circulation (Herbert, 1994).

Another group at risk of becoming vitamin B12 deficient is the elderly due to a greater prevalence of gastric atrophy and hypochlorhydria, which both lead to an insufficient absorption of food bound vitamin B12 (Baik & Russell, 1999). Indeed, others have reported a decrease in average serum vitamin B12 concentrations with advancing age in elderly populations (> 65 y) (Den Elzen et al., 2008, Green et al., 2005, Loikas et al., 2007, Nilsson-Ehle et al., 1991, Wahlin et al., 2002). There was no evidence of an age-related decline in serum concentrations of vitamin B12 among any of the diet groups in this study, which is similar to that reported in the United Kingdom National Diet and Nutrition Survey (Ruston et al., 2004) and may be because these studies did not include many elderly participants.

The finding that over 95% of vegans and 31% of vegetarians who were not using supplements failed to meet the RNI for daily vitamin B12 intake (1.5 μg/day from foods) was similar to that reported by others (Draper et al., 1993, Koebnick et al., 2004). Furthermore, even though vegetarian and vegan men who reported taking a vitamin B12 supplement had a higher intake of vitamin B12, serum concentrations of vitamin B12 were not affected. It is possible that supplement use was not accurately reported, some of the vitamin B12 supplements taken contained a type of inactive plant based vitamin B12 (Watanabe, 2007) or that a proportion of men taking a vitamin B12 supplement had been recently diagnosed with a vitamin B12 deficiency. There appears to be a degree of awareness among these participants of the need to supplement vegan and vegetarian diets, inasmuch as 20% of vegans and vegetarians reported taking vitamin B12 supplements regularly. However, because there was little difference in serum vitamin B12 between supplement and non-supplement users, it may be necessary to improve the understanding of the need to regularly consume supplements containing adequate amounts of the active form of vitamin B12.

Subclinical abnormalities are thought to emerge when serum concentrations of vitamin B12 fall below 111 pmol/l (Herbert, 1994). Over half of the vegans had serum vitamin B12 concentrations below 118 nmol/L and thus, these men have a higher risk of developing clinical symptoms related to vitamin B12 deficiency. Evidence of severe neurological damage as result of chronic vitamin B12 deficiency in vegans and vegetarians is rare; however, several case reports have shown neurological impairment that includes irreversible degeneration of the spinal cord, as well as difficulty in walking and handling utensils (Brocadello et al., 2007, Takahashi et al., 2006). There are very few studies that have looked for milder neurological symptoms among vegetarians and vegans who are vitamin B12 deficient.

In this study, serum concentration of vitamin B12 was used as a biomarker of vitamin B12 status, although recent evidence suggests that serum holoTC may be a more sensitive and specific biomarker of vitamin B12 status (Clarke et al., 2007, Hvas & Nexo, 2005). HoloTC is the fraction of vitamin B12 bound to transcobalamin that delivers vitamin B12 to cells that synthesise DNA and is thus considered the physiologically active component of vitamin B12 (Gibson, 2005). The concentrations of holoTC, MMA and tHcy were measured in a subgroup of the study participants; approximately 80% of men with serum vitamin B12 concentrations below the cut-point of 118 pmol/l had values for holoTC indicative of vitamin B12 deficiency. On the other hand, only a third of these men had values for both MMA and tHcy above the cut-points considered as biochemically vitamin B12 deficient. Moreover, whilst the cut points used in this study to identify those at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency has been used elsewhere (Ruston et al., 2004), others have used a higher cut-point (250 pmol/l) to define vitamin B12 deficiency (Lindenbaum et al., 1994). It is possible therefore that the true proportion of individuals with a vitamin B12 deficiency reported herein has been underestimated.

In conclusion, the results from this study show that vegetarians and vegans have much lower concentrations of serum vitamin B12 but higher concentrations of folate in comparison to omnivores. Mean serum vitamin B12 was not associated with the duration of adherence to a vegetarian or vegan diet, which may indicate that mechanisms that maintain circulating concentrations of vitamin B12 are upregulated in vegetarians and vegans. Further research into the health effects of vitamin B12 deficiency and depletion in vegans and vegetarians is warranted and vegetarians and vegans should ensure a regular intake of sufficient vitamin B12 from fortified foods and/or supplements.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in the EPIC-Oxford cohort for their invaluable contribution to the study, as well as the laboratory staff at King’s College London for the measurement of serum vitamin B12 and folate concentrations. This research was conducted during tenure of a Girdlers’ New Zealand Health Research Council Fellowship (FLC) and we further acknowledge the Dutch Cancer Society (AMJG).

Funding: Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, UK and the European Commission.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest TJK is a member of the Vegan Society, UK. The other authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- Baik HW, Russell RM. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:357–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham SA, Cassidy A, Cole TJ, Welch A, Runswick SA, Black AE, et al. Validation of weighed records and other methods of dietary assessment using the 24h urine nitrogen technique and other biological markers. Br J Nutr. 1995;73:531–50. doi: 10.1079/bjn19950057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A, Day K, Cassidy A, Khaw KT, et al. Comparison of dietary assessment methods in nutritional epidemiology: Weighed records v. 24 h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J Nutr. 1994;72:619–43. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocadello F, Levedianos G, Piccione F, Manara R, Pesenti F Francini. Irreversible subacute sclerotic combined degeneration of the spinal cord in a vegan subject. Nutrition. 2007;23:622–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Sherliker P, Hin H, Nexo E, Hvas AM, Schneede J, et al. Detection of vitamin B12 deficiency in older people by measuring vitamin B12 or the active fraction of vitamin B12, holotranscobalamin. Clin Chem. 2007;53:963–70. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.080382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane MG, Sample C, Patchett S, Register UD. Vitamin B12 Studies in Total Vegetarians (Vegans) J Nutr Environ Med. 1994;4:419. [Google Scholar]

- Davey GK, Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Knox KH, Key TJ. EPIC-Oxford: Lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:259–68. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Elzen WPJ, Westendorp RGJ, Frölich M, De Ruijter W, Assendelft WJJ, Gussekloo J. Vitamin B12 and folate and the risk of anemia in old age: The Leiden 85-plus study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2238–44. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper A, Lewis J, Malhotra N, Wheeler E. The energy and nutrient intakes of different types of vegetarian: A case for supplements. Br J Nutr. 1993;69:3–19. doi: 10.1079/bjn19930004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson RS. Principles of Nutritional Assessment. 2nd Ed Oxford University Press Inc.; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green TJ, Venn BJ, Skeaff CM, Williams SM. Serum vitamin B12 concentrations and atrophic gastritis in older New Zealanders. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:205–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad EH, Berk LS, Kettering JD, Hubbard RW, Peters WR. Dietary intake and biochemical, hematologic, and immune status of vegans compared with nonvegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:586–593S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.586s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert V. Staging vitamin B-12 (cobalamin) status in vegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1213–1222S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1213S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann W, Schorr H, Obeid R, Geisel J. Vitamin B-12 status, particularly holotranscobalamin II and methylmalonic acid concentrations, and hyperhomocysteinemia in vegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:131–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann W, Schorr H, Purschwitz K, Rassoul F, Richter V. Total homocysteine, vitamin B12, and total antioxidant status in vegetarians. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1094–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokin BD, Butler T. Cyanocobalamin (vitamin B-12) status in Seventh-day Adventist ministers in Australia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:576–578S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.576s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C, Huang P, Lu S, Li Y, Huang H, Lin B, et al. Plasma homocysteine levels in Taiwanese vegetarians are higher than those of omnivores. J Nutr. 2002;132:152–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvas A, Nexo E. Holotranscobalamin - A first choice assay for diagnosing early vitamin B12 deficiency? J Intern Med. 2005;257:289–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key TJ, Fraser GE, Thorogood M, Appleby PN, Beral V, Reeves G, et al. Mortality in vegetarians and nonvegetarians: Detailed findings from a collaborative analysis of 5 prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70 doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.516s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key TJ, Appleby PN, Spencer EA, Travis RC, Roddam AW, Allen NE. Mortality in British vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford) Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1613S–1619. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnick C, Hoffmann I, Dagnelie PC, Heins UA, Wickramasinghe SN, Ratnayaka ID, et al. Long-term ovo-lacto vegetarian diet impairs vitamin B-12 status in pregnant women. J Nutr. 2004;134:3319–26. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajčovičová-Kudláčková M, Blažíček P, Kopčová J, Béderová A, Babinská K. Homocysteine levels in vegetarians versus omnivores. Ann Nutr Metab. 2000;44:135–8. doi: 10.1159/000012827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbaum J, Rosenberg IH, Wilson PWF, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Allen LH, et al. Prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in the Framingham elderly population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:2–14. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Wright Z, Hvas A, Møller J, Sanders TAB, Nexø E. Holotranscobalamin as an Indicator of Dietary Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Clin Chem. 2003;49:2076–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.020743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loikas S, Koskinen P, Irjala K, Löppönen M, Isoaho R, Kivelä SL, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the aged: A population-based study. Age Ageing. 2007;36:177–83. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak D, Singer I, Manner M, Rust P, Genser D, Wagner K, et al. B-Vitamin Status and Concentrations of Homocysteine in Austrian Omnivores, Vegetarians and Vegans. Ann Nutr Metab. 2006;50:485. doi: 10.1159/000095828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann NJ, Li D, Sinclair AJ, Dudman NPB, Guo XW, Elsworth GR, et al. The effect of diet on plasma homocysteine concentrations in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:895–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson-Ehle H, Jagenburg R, Landahl S, Lindstedt S, Svanborg A, Westin J. Serum cobalamins in the elderly: A longitudinal study of a representative population sample from age 70 to 81. Eur J Haematol. 1991;47:10–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1991.tb00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid R, Geisel J, Schorr H, Hübner U, Herrmann W. The impact of vegetarianism on some haematological parameters. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:275–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauma A, Torronen R, Hanninen O, Mykkanen H. Vitamin B-12 status of long-term adherents of a strict uncooked vegan diet (‘living food diet’) is compromised. J Nutr. 1995;125:2511–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.10.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruston D, Hoare J, Henderson L, Gregory J, Bates CJ, Prentice A, et al. Nutritional status (anthropometry and blood analytes), blood pressure and physical activity. 2004.

- Takahashi H, Ito S, Hirano S, Mori M, Suganuma Y, Hattori T. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord in vegetarians: Vegetarian’s myelopathy. Intern Med. 2006;45:705–6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlin A, Bäckman L, Hultdin J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG. Reference values for serum levels of vitamin B12 and folic acid in a population-based sample of adults between 35 and 80 years of age. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:505–11. doi: 10.1079/phn200167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann A, Koschizke JW, Leitzmann C, Hahn A. Homocysteine and cobalamin status in German vegans. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:467–72. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability. Exp Biol Med. 2007;232:1266–74. doi: 10.3181/0703-MR-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]