Dear Editor:

Although research on sex among elder individuals challenges cultural stereotypes, there is increasing epidemiologic and biologic research that reveals elders as a potentially important HIV risk group.1 It is known that the prevalence of sexual activity declines with age among those over 50 (elders); however, clinicians often fail to elicit a complete sexual history from elder patients and patients may be hesitant about providing details regarding their sexual behaviors.2 Additionally, most sexual behavior surveillance programs focus on the 15–49 age group, perpetuating the assumption that elders have limited sexual risk. While health programs for young patients routinely include sexual health, there are fewer initiatives and public health programs for subsets of elders shown to be at risk for sexually transmitted infection (STI) and HIV. Existing research suggests that compared with younger individuals, elders may not only have a higher per-sex act risk of HIV acquisition, but also have a longer delay between start of symptoms and seeking care and more rapid disease progression.1

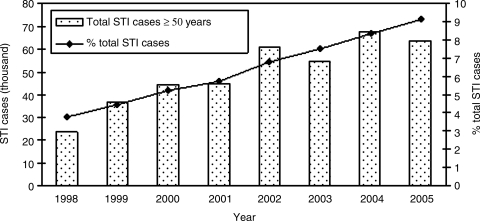

The population in China is steadily aging, with elders comprising 18% of the population in 2000 and estimated to reach 32% of the total population in 2020.3 Demographic changes of historic proportions have increased both the absolute and relative numbers of elders in China. Similar to reports from other countries,4 elders in China constitute a growing proportion of total STI cases. Reported STI cases are defined by criteria set by the Chinese Ministry of Health and include both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. In 1998, 3.8% of all reported STI cases were among elders in China; this proportion of elder STI cases increased to 9.1% in 2005 (Fig. 1).5 The National STD Surveillance System of the Chinese CDC collects sentinel data on the incidence of five STIs; syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, condylomata acuminate, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. For these STIs, male elders account for 15.8% of all cases, and female elders make up 9.8% of all cases. There is male predominance in all reported STIs, with the exception of gonorrhea, where elder females account for approximately 20% of all cases, with elder men constituting less than 9% of sentinel cases. Recent data collected from these sites show that approximately 30% of syphilis cases, 11% of condylomata acunimata, and 9% of HSV cases are in elder men. Except for gonorrhea, elder men have roughly double the number of cases of each respective STI compared to female elders.6 Demographic factors also help describe the population of elders with increasing prevalence of STIs. For example, syphilis cases have increased 28% in those patients who are self-described as retired. Additionally, roughly 60% of all reported cases are in the eastern and southern coastal cities and provinces, where many elders reside in the densely populated urban centers.7 As elder individuals continue to shoulder a greater burden of disease, careful attention should be given to this growing population in order to reduce morbidity and decrease transmission to sexual partners.

FIG. 1.

Trends of sexually transmitted infection (STI) in elders (≥50 years) in China during the period 1998–2005.5 Absolute number of reported STI cases and percent of total STI cases are shown.

There are a range of behavioral, social, and biologic factors that may underpin increasing STI risk among the elders in China, including physiologic factors, use of commercial sex, infrequent condom use, cross-generational sexual networks, and low rates of STI testing. Physiologic changes of the aging process, such as increased friability of the vaginal mucosa and ensuing microabrasions as a result of sexual intercourse, can facilitate STI transmission in elder women.4 In this population, there is likely a low level of awareness regarding the risk factors for STI and HIV transmission or for proper diagnosis and treatment of STIs.

Unfortunately, information on the sexual risk factors of elders in China is scant. Commercial sex in China is widespread,8 and high rates of STI have been documented among commercial sex workers.9 In certain areas of China, elder individuals are more likely to purchase commercial services from low-tier sex workers in whom syphilis prevalence was more than 30%.10 Additionally, condom use is particularly low among elders, in part because older individuals may view condom use primarily as a contraceptive measure, and may be less aware of its role in preventing STI.4

Unlike commercial sex workers and others at high-risk for STIs, the sexual networks and social norms of elders have not been routinely studied in China and could contribute significantly to risk factors such as consistent condom usage.11

Especially in light of China's expanding syphilis epidemic, these risk factors raise concern for HIV/STI transmission among elders. Syphilis infection has become a major public health threat in China.9,12 After virtually eliminating all STI in China by 1964, in the past two decades China has seen a tremendous resurgence of syphilis, based on data from mandatory case reporting and sentinel surveillance sites. Syphilis incidence rose from 0.2 cases per 100,000 in 1993 to 21 cases per 100,000 in 2008.7 The 15- to 49-year-old population group constitutes 70% of all syphilis infections in China7 and thus most studies on syphilis have focused on this population. However, age-stratified analysis of syphilis incidence in China reveals a bimodal distribution, with an initial peak in sexually active adults at approximately 37 years,12 and a second peak among older age groups (Fig. 2). As a result of ignorance to this subgroup, there are limited data on syphilis prevalence among elders. Despite these limitations, both the total number of STI among elders in China and the percentage of total STI cases among elders has increased from 1998 to 2005 (Fig. 1). More detailed data during 2006–2008 suggests that a greater proportion of syphilis cases in China are attributable to elders, with over a quarter of total reported cases in those over 50 years in 2008.7

FIG. 2.

Reported incidence of syphilis cases per 100,000 by age group in China in 2008.7

The increase in reported syphilis cases among elder patients can be explained several ways. The increased number of cases could reflect a true increased incidence in the elder population. Simultaneously, more thorough screening efforts, now standard protocol for hospital admission, have likely captured latent syphilis cases that might have gone otherwise undetected and untreated. Because elders tend to have higher numbers of hospital admissions than the 20–25 age group, this could help explain the increase in reported syphilis incidence. Any overreporting of cases in elders relative to younger age groups could also impact the age-stratified analysis of cases. Although studies do not differentiate between active and latent syphilis infection, current descriptions of sexual activity in elder individuals2 suggests that new infections are possible, in addition to latent cases that are increasingly discovered through screening programs.

A closer look at elder individuals from the largest STI patient study in China to date confirms a high burden of risky sexual behaviors and syphilis infection. This cross-sectional study of 11,461 STI clinic patients from eight cities in Guangxi Province included 944 individuals 50 years and older.8 Among elders, 46% acknowledged purchasing commercial sex, nearly 24% stated they had multiple sexual partners and less than 4% acknowledged condom use (unpublished data). Syphilis infection was present in 12.7% and HIV infection was detected in 1.4% of elders. Nearly three quarters of these syphilis cases had rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titers higher than 1:8. Syphilis infection was significantly associated with reporting multiple sexual partners.8 In the elder subpopulation sample, over 60% of syphilis infected individuals reported purchasing commercial sex. Eight percent of elder clients of commercial sex workers reported condom use at their most recent sexual encounter. The prevalence of same sex behaviors among elders is also unclear although it has been observed in this subgroup in China, and this demands greater research.11 The data suggest that some elders share common sexual risk factors with younger age groups and are at increased risk of HIV and STIs.

An expanding older population and changing sexual behaviors act synergistically to help explain the steady increase in syphilis among China's elder population and all documented cases should be treated in order to prevent further transmission or complications of the disease. Clinician training should emphasize awareness and sensitivity to manifestations of STIs in elder patients. For example, the waning immune system in elder persons is more likely to allow for reactivation of latent syphilis, leading to cardiovascular or neurologic complications that can be mistakenly attributed to the normal aging process.

Traditional control efforts and prevention programs for HIV and other STIs in China are notable for their lack of heterogeneity in target populations, focusing almost exclusively on high risk populations such as injection drug users and female sex workers. Given that these groups mainly consist of young persons, older persons are often overlooked despite sexual behaviors, such as patronizing commercial sex workers,9,10 which also put them at risk of acquiring STI. Novel sexual health campaigns targeting elder populations should be investigated, drawing on the successes and failures of behavioral approaches that have been used in other age groups. In order for sexual health programs to effectively target this growing, at-risk population of older individuals, sexual behaviors among elders need to be better defined and monitored.

While it is acknowledged that syphilis predominantly affects younger age groups, empiric evidence in China demonstrates that elder people's sexual behaviors also put them at risk for infection. Unfortunately, general practitioners respond to later life sexuality stereotypes, rather than the reality of elder people's experiences, thus more provider education is needed to properly screen and counsel elder patients about sexual health. STI counseling regarding safer sex practices should be considered for persons of all ages, and culturally appropriate, age-specific messaging should be developed and directed toward this group in order to raise awareness of syphilis and other STIs.

Understanding the epidemiology of syphilis and other STIs in the aging population in China is an important first step in improving care for this growing population. Increased monitoring of disease prevalence among this group, more comprehensive understanding of the sexual networks of elders, and consideration for the health-seeking behaviors of this population should lead to a better understanding of this group and their risk factors for STIs. Further behavioral research projects are needed to understand the reasons for elder sexual risk in China. This information will pave the way for better prevention and the development of specific elder interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Center for STD Control of China CDC, the UNC Center for AIDS Research, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center.

Funded by UNC Fogarty AIDS International Research and Training Program (NIH FIC D43 TW01039) and UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Project (A70577).

References

- 1.Schmid GP. Williams BG. Garcia-Calleja JM, et al. The unexplored story of HIV and ageing. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:162–A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindau ST. Schumm LP. Laumann EO. Levinson W. O'Muircheartaigh CA. Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Database. www.census.gov/cgi-bin/ipc/idbagg. [Apr 8;2009 ]. www.census.gov/cgi-bin/ipc/idbagg

- 4.Xu F. Schillinger JA. Aubin MR. St Louis ME. Markowitz LE. Sexually transmitted diseases of older persons in Washington State. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:287–291. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200105000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCSTD/CCDC. 2005 National report of epidemiological data on syphilis and gonorrhea. Bull STI Prev Control. 2006;20:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCSTD/CCDC. 2008 National report of epidemiological data on STDs from sentinel sites in China. Bull STI Prev Control. 2009;23:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.NCSTD/CCDC. 2008 National report of epidemiological data on syphilis and gonorrhea. Bull STI Prev Control. 2009;23:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SP. Yin YP. Gao X, et al. Risk of syphilis in STI clinic patients: A cross-sectional study of 11,500 cases in Guangxi, China. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:351–356. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruan Y. Cao X. Qian HZ, et al. Syphilis among female sex workers in southwestern China: Potential for HIV transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:719–723. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218881.01437.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang QQ. Yang P. Gong XD. Syphilis prevalence and high risk behaviors among female sex workers in different settings. Chin J AIDS STD. 2009;15:398–401. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H. Feng T. Feng H. Cai Y. Rhodes AG. Grusky O. Egocentric networks of Chinese men who have sex with men: Network components, condom use norms, and safer sex. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:885–893. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ZQ. Zhang GC. Gong XD, et al. Syphilis in China: Results of a national surveillance programme. Lancet. 2007;369:132–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]