Abstract

A novel method for B1+ field mapping based on the Bloch-Siegert shift is presented. Unlike conventionally applied double-angle or other signal magnitude-based methods it encodes the B1 information into signal phase, resulting in important advantages in terms of acquisition speed, accuracy and robustness. The Bloch Siegert frequency shift is caused by irradiating with an off-resonance RF pulse following conventional spin excitation. When applying the off-resonance RF in the kHz range, spin nutation can be neglected and the primarily observed effect is a spin precession frequency shift. This shift is proportional to the square of the RF field magnitude B12. Adding gradient image encoding following the off-resonance pulse allows one to acquire spatially resolved B1 maps. The frequency shift from the Bloch-Siegert effect gives a phase shift in the image that is proportional to B12. The phase difference of two acquisitions, with the RF pulse applied at two frequencies symmetrically around the water resonance is used to eliminate undesired off-resonance effects due to B0 inhomogeneity and chemical shift. In-vivo Bloch Siegert B1 mapping with 25 seconds / slice is demonstrated to be quantitatively comparable to a 21 minute double-angle map. As such this method enables robust, high resolution B1+ mapping in a clinically acceptable time frame.

Keywords: B1 mapping, RF mapping, flip angle, Bloch Siegert shift, off resonance, parallel transmit

INTRODUCTION

A wide variety of B1 mapping methods have been developed to date, however no single one has emerged yet in widespread application. B1 mapping is used in diverse applications in MR- including transmit gain adjustment to produce specific flip angle RF pulses, design of multi-transmit channel RF pulses (1-3), T1 mapping and other quantitative MRI (4), and chemical shift imaging.

Generally, B1 mapping methods fall into two classes: signal magnitude, or signal phase-based. The large majority of B1 mapping methods depend on changes in signal magnitude based on RF flip angle. Existing methods in this category include fitting progressively increasing flip angles (5), stimulated echoes (6), image signal ratios (7-10), signal null at certain flip angles (11), and comparison of spin echo and stimulated echo signals (12).

These methods suffer from combinations of the following problems: T1 dependence, long acquisition times-mainly from acquiring many images, and/or a long TR to mitigate the T1 dependence, inability to use some of these methods with slice-selection, or in a multi-slice acquisition, inaccuracy over a large range of B1 especially at low flip angles or flip angles close to 90° or 180°, and large RF power deposition in the case of B1 mapping sequences based on large flip angles or reset pulses to mitigate the T1 dependence.

There are far fewer phase-based B1 mapping methods. One method by Morrell uses the phase accrued from a 2α - α flip angle sequence to determine B1 (13). This method has the same long TR requirement as the signal magnitude-based sequences, although it is effective and more accurate over a larger range of flip angles than a double-angle signal magnitude-based B1 map (14). A very different phase-based approach was proposed by J.Y. Park and M. Garwood, where they utilize the B1-dependent phase produced by adiabatic hyperbolic secant half- and full-passage pulses (15). This method nicely eliminates the problems of T1 and B0 dependence, however SAR is a significantly limiting factor in applying this clinically at high field.

Here, we describe a novel phase-based B1 mapping method based on the Bloch-Siegert shift(16). This Bloch-Siegert shift is utilized to create a |B1|-dependent signal phase. The resulting B1 mapping method is shown here to be robust to TR, T1 relaxation, flip angle, chemical shift, background field inhomogeneity, and magnetization transfer. Because of this insensitivity, accurate Bloch-Siegert based B1 maps can be acquired very quickly with a short TR.

THEORY

The term Bloch-Siegert shift has been used to describe the effect where the resonance frequency of a nucleus shifts when an off-resonance RF field is applied (16,17). This effect is an additional contribution to the static B0 field that arises from the off-resonance component of the RF field. In the case where RF is applied either far enough off-resonance and/or with a pulse shape such that it does not cause spin excitation, the spins experience a change in precession frequency without excitation (18). The spin precession frequency shifts away from the off-resonance irradiation, and is dependent on the magnitude of the B1 field, and the difference between the spin resonance and RF frequency ωRF.

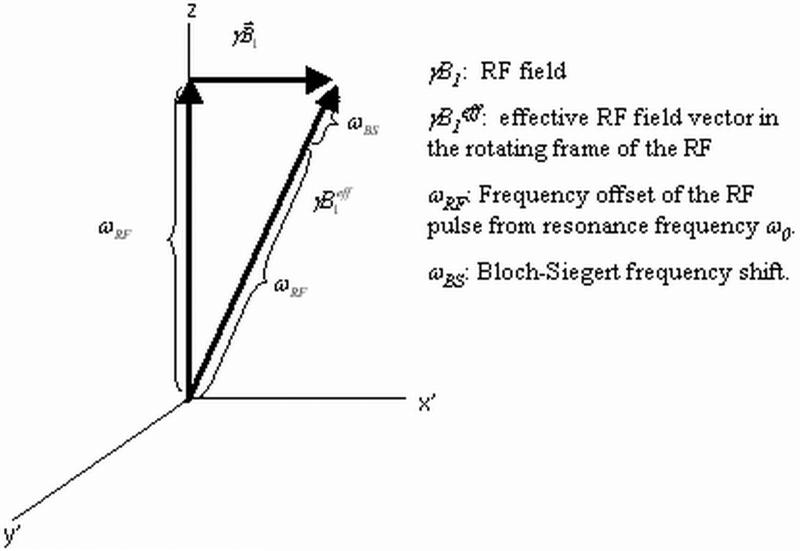

Figure 1 shows the effective B1 field in the RF rotating frame (B1eff) when the RF is applied off-resonance at frequency ωRF. The frequency difference between spin precession and the RF frequency can be visualized as a constant magnetic field along z. In this rotating frame the B1eff field is constant, and is given by Eqn 1:

| [1] |

For a large off resonance ωRF >> γB1 this results in the component ωBS of the B1eff field vector which is a small constant field approximately along the main magnetic field axis. This additional field constitutes the Bloch-Siegert shift and results in the spin precession frequency shift coming from off-resonance RF irradiation.

Figure 1.

B1 field in the rotating frame of the RF. The frame rotates at frequency ω0 + ωRF. In this frame, the B1 field is static, where as the spins rotate at ωRF. The Bloch-Siegert frequency shift ωBS is a constant field in this rotating frame along the effective RF field vector γB1eff.

A simple analytical relationship for the Bloch-Siegert shift ωBS can be derived from Figure 1. Under the assumption of large, relative off-resonance:

| [2] |

a trigonometric identity can by used to solve for ωBS according to:

| [3] |

| [4] |

This derivation is described in detail by Ramsey in a theoretical paper in Phys Rev. 1955 (17). This paper first describes the case dealt with here where a single non-resonant frequency is applied, and later deals more generally with irradiation at multiple non-resonant frequencies.

In practical application, the Bloch-Siegert shift has been used for determining the magnitude of a B1 decoupling field in solid state spectroscopy (19,20). However to the best knowledge of the authors this has never been applied in MR imaging.

The Bloch-Siegert shift can be applied to B1 field mapping as follows: An off-resonance RF pulse of frequency ωRF is applied immediately after excitation in an imaging sequence. The RF pulse shape and frequency is chosen such that it does not excite spins in the sample. The frequency shift of spins during the off-resonant RF pulse results in a phase shift in the image that can be used to determine the spatial B1 magnitude. The phase shift φBS due to the Bloch-Siegert shift is given by:

| [5] |

The expected phase shift can be calculated from Eqn. 5 for any arbitrary pulse B1(t) with constant or time dependent frequency offset ωRF(t).

The relationship between Bloch-Siegert phase shift and the peak B1 of a generalized RF pulse is given by Eqn. 6:

| [6] |

| [7] |

KBS is a constant that describes the phase shift (radians/gauss2) for a given RF pulse. For example: for a hard pulse, 4 kHz off resonance, KBS = 14.23 radians/gauss2/msec. B1,peak is the magnitude of the maximum point in the RF waveform B1(t).

Phase-based methods usually require taking the difference of two scans to remove additional, undesired phase effects in the image. The difference in phase between the two scans gives the Bloch-Siegert phase shift, removing transmit excitation and receive phases, other sequence related phase, and the phase shift from off-resonance B0. All these phase factors are the same in both scans. Acquiring two scans- one with the RF pulse at +ωRF, and one at −ωRF enables one to calculate B1. Applying the off-resonance RF symmetrically around the water peak removes the B0-inhomogeneity and chemical shift dependence of the Bloch-Siegert shift as well. For off-resonance spins precessing at frequency ω0 + ωB0, Eqn. 4 for the Bloch Siegert frequency shift becomes:

| [8] |

By a 2nd order Taylor expansion, assuming ωB0 << ωRF:

| [9] |

The Bloch-Siegert phase shift of a spin at B0 offset of ωB0 is given by:

| [10] |

The ωB0 dependent term drops out when one takes the phase difference between two scans with the off-resonance pulse at symmetric +/− ωRF frequencies. The result is a phase shift that is up to first order independent of off-resonance frequency.

The percentage error in B1 calculated from the phase difference of two scans with off-resonance RF applied at +/− ωRF, where there is a B0 offset of ωB0 is given by Eqn’s 11 and 12:

| [11] |

| [12] |

This percentage error in B1 calculation as a function of B0 offset is shown in Figure 2. The error is shown for RF pulses at off-resonance frequencies 2, 4, and 8 kHz, over a range of +/− 1 kHz B0 inhomogeneity.

Figure 2.

Percentage error in B1 calculation as a function of B0 offset over a range of 1 kHz. The error is calculated from Eqns. 11 and 12, for RF pulses at off-resonance frequencies of 2, 4, 8 kHz.

METHODS

The sequences in Figure 3 were implemented on a 3 Tesla GE DVMR scanner, (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). 15 human subjects were studied in accordance with institutional review board guidelines for in-vivo research. All subjects provided informed consent. A basic gradient echo sequence was modified by including an off-resonance Fermi pulse immediately following excitation. A basic spin echo sequence was modified by including two Fermi pulses, applied around a refocusing pulse. All gradient echo images shown in this work were acquired with an 8 msec Fermi saturation pulse, and frequency offsets of ωRF = +/− 4 kHz relative to water. All spin echo B1 maps were acquired with two 6 msec Fermi saturation pulses, and frequency offsets of ωRF = +/− 4 kHz relative to water. Figure 4 shows the 8 msec Fermi pulse, and its frequency excitation profile. A frequency profile with minimal on-resonance excitation is necessary to not excite spins in the sample.

Figure 3.

Gradient and spin echo sequences, modified for B1 mapping. The gradient echo sequence has an 8 msec off-resonance Fermi pulse at off-resonance frequency ωRF following excitation. The spin echo sequence has two 6 msec off-resonance Fermi pulses. The first pulse is at off-resonance frequency ωRF and the second at −ωRF .

Figure 4.

Normalized B1(t) and corresponding frequency excitation profile for an 8 msec Fermi pulse, and ωRF = 4 kHz.

For the 8 msec 4 kHz off resonance Fermi pulse used in the gradient echo experiments described here, KBS = 74.01 radians/gauss2. For the 6 msec 4 kHz off resonance Fermi pulse used in the spin echo experiments described here, KBS = 55.26 radians/gauss2. The spin echo sequence contains two 6 msec Fermi pulses for a total KBS for the sequence of 110.52 radians/gauss2. The relationship between phase shift and B1,peak is shown in Figure 5 for the 8 msec Fermi pulse. Also shown is a comparison between the phase shift predicted by the analytical expression in Eqn. 6 and the phase shift predicted by numerical Bloch simulation of this off-resonance pulse.

Figure 5.

Phase shift φBS vs. |B1| for an 8 msec Fermi pulse at 4 kHz. Simulated by the analytical expression of Eqn. 6, and numerical Bloch simulation.

The Fermi RF pulse is used regularly for magnetization transfer preparation- which has similar RF pulse requirements as our case here (21,22). The relationship between phase shift and B1,peak can be calculated similarly for any arbitrary RF pulse. Figure 6 shows a comparison of KBS for four choices of RF pulses: the hard pulse, Fermi, and adiabatic sech/tanh, and tanh/tan pulses (23). Also shown is a comparison of the width of the frequency band that contains 99% percent of spin excitation for these pulses.

Figure 6.

Comparison of four RF pulses, all of 8 msec pulse length, at 4 kHz off-resonance, relative to water. The hard pulse, Fermi, adiabatic hyperbolic secant (with a time varying frequency sweep ωRF(t) of +/−2kHz around 4 kHz), and the adiabatic tanh/tan pulse (with a time varying frequency sweep ωRF(t) of +/−20kHz around 4 kHz). KBS (radians/gauss2) is calculated for these four pulses, as well as the frequency range that contains 99% of spin excitation. This Fermi pulse is used for all subsequent experiments shown here.

RESULTS

Gradient echo Bloch-Siegert B1 maps and double angle maps were acquired from a silicon oil phantom, and a saline phantom with three inner subcompartments filled with milk to assess sensitivity of this method to chemical shift and to magnetization transfer. A GE birdcage transmit/receive head coil was used for RF transmission and reception.

Figure 7a shows a double angle B1 map of the silicon oil phantom. The two gradient echo images were acquired with TE = 10 msec, TR = 5 sec, flip angles α = 60°, 2α =120°, slice thickness 1 cm, in plane resolution 128×128. The flip angle map for the 60° image was calculated by (24):

| [13] |

where S2α and Sα are the signal magnitudes of the 2x and 1x flip angle images. The B1 map calculated for the 60° flip angle RF pulse is shown here for comparison with the Bloch-Siegert B1 maps. Figure 7b shows two Bloch-Siegert B1 maps taken with TE = 15 msec, and TR of 70 and 2000 msec, which demonstrate lack of TR-dependence. Figure 7c shows the percent difference between the double angle map and the 70 msec TR Bloch-Siegert map. These match to within 2%.

Figure 7.

a. Double angle B1 map, calculated from two scans acquired with a 3.2 msec sinc pulse having flip angles of α = 60°, 2α = 120°, TE = 10 msec, TR = 5 sec. Slice thickness = 1 cm, 128×128 resolution. b. Gradient echo Bloch-Siegert B1 map, acquired with TE = 15 msec, TR = 70 msec (left), 2 sec. (right), 8 msec, +/−4 kHz Fermi pulse. c. Error between the two methods: Double Angle map / Bloch-Siegert map * 100% d. B1 maps acquired with the amplifier output at 0.33, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.5 * B1,peak, where B1,peak = 0.073 gauss B1 field produced at the center of the slice. The B1 maps are displayed rescaled to 0.073 gauss for comparison. e. Bloch-Siegert B1 maps of a saline phantom with three milk compartments acquired with the 8 msec Fermi pulse at off-resonance frequencies of 2, 4, 6, and 8 kHz relative to the water resonance.

Figure 7d shows Bloch-Siegert B1 maps as a function of peak B1 power. Four Bloch-Siegert B1 maps were acquired with B1,peak = 0.11, 0.073, 0.055, 0.037, 0.024 gauss. B1,peak was controlled by scaling the exciter output by 1.5, 1.0, 0.75, 0.5, 0.33. The B1 maps are scaled by these factors for easier comparison.

Figure 7e shows Bloch-Siegert maps of the saline/milk phantom acquired with the 8 msec Fermi pulse at off-resonance frequencies of 2, 4, 6, and 8 Hz relative to the water resonance. No effect of chemical shift or magnetization transfer is evident in the milk or water compartments.

The B1 maps in Figure 7d and e were acquired with TR = 70 msec. Total scanning times were 21.3 min. for the double angle map, and 18 sec. for the Bloch-Siegert maps.

This was repeated in-vivo in the brain, sagittal orientation, with a GE birdcage transmit/receive head coil (Figure 8). There is a small difference in the magnitude images with the off-resonance pulse (Figure 8a, b.) and without the off-resonance pulse (Figure 8c). This is likely the result of magnetization transfer, however this does not cause any obvious artifacts in the B1 map. The double angle map in Figure 8d overestimates the B1 field in the CSF, resulting from the known T1 dependence of this method and the less than optimal TR of 3 seconds. T1 dependence is not evident in the Bloch Siegert B1 map of Figure 8e.

Figure 8.

a, b. Magnitude gradient echo images with 8 msec off-resonance Fermi pulse, ωRF = +/− 4 kHz. c. Same image acquisition, without the off-resonance pulse. d. Double angle B1 map, 128×128, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, TE = 12 msec, TR = 3 sec. Flip angles α = 45° 2α = 90°. e. Bloch Siegert map calculated from the phase difference between images a. and b. The peak B1 of the Bloch-Siegert map was twice the peak B1 used in the double angle map. Resolution 128×128, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, TE = 12 msec, TR = 100 msec, off resonance pulse: 8 msec Fermi, ωRF = +/− 4 kHz.

Additional gradient echo double angle and Bloch-Siegert B1 maps acquired in vivo in a human leg, sagittal orientation, using a GE birdcage transmit/receive knee coil are presented in Figure 9. No effects are evident in the Bloch-Siegert B1 map from either magnetization transfer or chemical shift from lipids.

Figure 9.

a. Double angle B1 map, resolution 128×128, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, TE = 12 msec, TR = 5 sec. Flip angles α = 60° 2α = 120°. b. Gradient echo Bloch-Siegert map, resolution 128×128, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, TE = 12 msec, TR = 100 msec, off resonance pulse: 8 msec Fermi, ωRF = +/− 4 kHz.

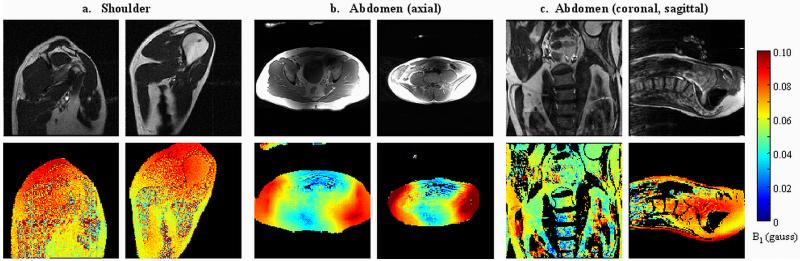

Figure 10 shows spin echo images and corresponding spin echo Bloch-Siegert B1 maps acquired in vivo in two subjects in the shoulder (10a), and four in the abdomen (10b,c). A GE DVMR whole-body transmit coil was used for the shoulder images. The abdomen B1 maps were acquired on a GE Signa Excite HDx system using the body transmit coil. Signal reception was done with the body transmit/receive coil for the shoulder, and a local 8-channel receive array (GE) for the abdomen. All images were acquired without breath holding. These images show no discontinuity in the B1 maps between water and lipids. The abdomen B1 maps have artifacts along the phase-encoding direction from breathing and blood flow through large vessels, but not to an extent that significantly impacts the B1 maps.

Figure 10.

Spin echo Bloch-Siegert B1 maps, acquired with two 6 msec, +/− 4 kHz off-resonance Fermi pulses, applied symmetrically around a 3.2 msec sinc refocusing pulse. The Fermi pulses had the same peak B1 as the excitation pulse. TE = 28 msec, TR = 200 msec, resolution = 128×128, slice thickness = 1 cm. a. Shoulder, two subjects, taken with GE DVMR whole body transmit/receive coil. b. Abdomen, axial orientation two subjects, taken with whole body transmit, GE 8-channel torso receive array. c. Abdomen, sagittal and coronal orientations.

DISCUSSION

The Bloch-Siegert shift gives a fast, accurate, robust, and conceptually straightforward method for measuring B1 field maps. The Bloch-Siegert shift provides a detectable phase shift to use for B1 mapping, providing one uses a long enough off-resonance RF pulse with amplitudes compatible with clinical applications. The associated increase in echo time can be afforded for most in-vivo applications. In general, phase sensitive B1 mapping methods have a significant advantage over signal magnitude based methods in scan time and accuracy over a wide dynamic range of flip angles (14). The Bloch-Siegert method in particular is shown here to be insensitive to T1, TR, chemical shift, magnetization transfer, and inhomogeneous B0 within a range reasonably expected in vivo.

This method will work with a large variety of off-resonance pulse shapes. The optimal pulse shape for this method would be one that maximizes the integral in Eqn. 5, but does not directly excite spins in the sample. Several pulse shapes were considered- the hard pulse, adiabatic hyperbolic secant, Gaussian, as well as the Fermi pulse. The latter offered a good choice in terms of maximizing the integral of Eqn. 5, and minimizing on-resonance excitation.

The Bloch-Siegert phase shift produced by a single off-resonance RF pulse is B0 dependent. However, the phase difference between two scans with the off-resonance pulse at approximately symmetric frequencies around the on-resonance water peak, is independent of B0 for ωB0 << ωRF. One would choose the RF off-resonance frequency ωRF to satisfy this condition, as well as to avoid on-resonance excitation. The off-resonance frequency ωRF of 4 kHz was chosen for this pulse based on the criteria that the pulse excite <1% of spins within a ±1 kHz range around the center resonance frequency.

The off-resonance Fermi pulse used here to produce the Bloch-Siegert shift is similar to off-resonance RF pulses typically used in a magnetization transfer sequence. There is a magnitude difference between in-vivo images acquired with and without the off-resonance RF pulse that is likely due to magnetization transfer, flow, and motion. There is a small asymmetry in the magnitude of the two images with the off-resonance pulse on either side of the water peak (25). However, no phase contribution from the magnetization transfer is evident in any of the in-vivo experiments, or the milk compartment phantom experiments.

Because of the insensitivity of this method to relaxation and TR, one would likely use as short a TR as possible. The SNR of a Bloch-Siegert B1 map is dependent on the base SNR of the two acquired images, and the phase shift between the images. Scan time in most cases will be limited at lower field by a tradeoff between imaging time and SNR, and at high field (≥ 3 Tesla) by clinical SAR limits.

The Bloch-Siegert phase shift scales with the integrated area of B12, as does SAR. For the gradient echo sequence: All imaging demonstrated here in vivo including acquisitions with TR of 50 msec was within all SAR limits as measured by conventional scanner power monitoring. At 3 Tesla, with a TR of 35 msec, and peak B1 of 0.2 gauss, we skirt the short term (10 second) SAR limits. However, our in-vivo experiments gave more than adequate signal to noise with peak B1 = 0.07 gauss and TR of 50 msec. This was well within the long-term SAR limits for continuous scanning. At higher field strengths, one can extend the TR. The spin echo sequence presented here was more SAR intensive, but could be run continuously with a body transmit coil with a peak Fermi pulse B1 of 0.1 gauss with a TR of 200 msec.

Even at longer TR the time advantage of this method is maintained. This method is fully compatible with EPI, spiral readout, or other imaging acceleration methods, which can additionally reduce scan time and/or SAR.

The Bloch-Siegert shift was used in this work to measure the magnitude of the B1+ field, needed in a large number of MR applications. A subclass of these applications may also benefit from knowledge of the phase of the B1+ field, or of the receive B1− sensitivity. While the B1+ phase and the B1− profile can not be determined directly from the Bloch-Siegert shift, they may be obtained using information collected in the Bloch-Siegert B1+ mapping scans. For example, in a manner similar to the one described by Wang et al. (26), the B1− profile can be obtained using a fast third acquisition with the contrast between tissues minimized, and the B1+ map from the Bloch-Siegert shift. B1 phase is conventionally determined from the phase difference between images where each coil transmits individually. One could similarly take the phase difference between images used for Bloch-Siegert B1 maps where each coil is used individually for excitation. It may be the case that acquiring B1 magnitude from the Bloch-Siegert shift, and B1 receive from a second scan is a beneficial method for parallel transmit applications as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Mohammed Khalighi and W. Thomas Dixon for useful discussions on obtaining the phase of the B1+ field, and off-resonance error in Bloch-Siegert B1 maps.

This research was supported by NIH grant 5R01EB005307-02.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katscher U, Börnert P, Leussler C, van den Brink JS. Transmit SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:144–150. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y. Parallel excitation with an array of transmit coils. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:775–784. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu D, King KF, Zhu Y, McKinnon GC, Liang ZP. Designing multichannel, multidimensional, arbitrary flip angle RF pulses using an optimal control approach. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:547–560. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warntjes JB, Leinhard OD, West J, Lundberg P. Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: Optimization for clinical usage. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:320–329. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hornak JP, Szumowski J, Bryant RG. Magnetic field mapping. Magn Reson Med. 1988;6:158–163. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akoka S, Franconi F, Sequin F, Le Pape A. Radiofrequency map of an NMR coil by imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;11:437–441. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(93)90078-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stollberger R, Wach P, McKinnon GC, Justich E, Ebner F. RF field mapping in vivo; Proceedings of the 7th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; San Francisco, CA, USA. 1988.p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier JK, Glover GH. Method for mapping the RF transmit and receive field in an NMR system. US Patent 5001428. 1991

- 9.Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Nayak KS. Saturated double-angle method for rapid B1+ mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1326–1333. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr AB, Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Piel JE, Giaquinto RO, Watkins RD, Zhu Y. Accelerated B1 mapping for parallel excitation; Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Berlin, Germany. 2007.p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell NG, Tofts PS. Fast, accurate, and precise mapping of the RF field in vivo using the 180° signal null. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:622–630. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiru F, Klose U. Fast 3D radiofrequency field mapping using echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1375–1379. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrell GR. A phase-sensitive method of flip angle mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:889–894. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrell GR, Schabel M. A noise analysis of flip angle mapping methods; Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, HI, USA. 2009.p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JY, Garwood M. B1 mapping using phase information created by frequency-moduated pulses; Proceedings of the 16th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Canada. 2008.p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloch F, Siegert A. Magnetic resonance for nonrotating fields. Phys Rev. 1940;57:522–527. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey NF. Resonance transitions induced by perturbations at two or more different frequencies. Phys Rev. 1955;100(4):1191–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steffen M, Vandersypen LMK, Chuang IL. Simultaneous soft pulses applied at nearby frequencies. J Magn Reson. 2000;146(2):369–374. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vierkotter SA. Applications of the Bloch-Siegert shift in solid-state proton-dipolar-decoupled 19F MAS NMR. J Magn Reson. 1996;118:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michal CA, Hastings SP, Lee LH. Two-photon Lee-Goldburg nuclear magnetic resonance: Simultaneous homonuclear decoupling and signal acquisition. J Chem Phys. 2008;128(5):052301. doi: 10.1063/1.2825593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin C, Bernstein MA, Gibbs GF, Huston Reduction of RF power for magnetization transfer with optimized application of RF pulses in k-space. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(1):114–121. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Grist TM, Mistretta CA. Dispersion in magnetization transfer contrast at a given specific absorption rate due to variations of RF pulse parameters in the magnetization transfer preparation. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(6):957–962. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang TL, van Zijl PC, Garwood M. Fast broadband inversion by adiabatic pulses. J Magn Reson. 1998;133(1):200–203. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Mao W, Qiu M, Smith MB, Constable RT. Factors influencing flip angle mapping in MRI: RF pulse shape, slice-select gradients, off-resonance excitation, and B0 inhomogeneities. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:463–468. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakely J, Smith SA, van Zijl PC, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(4):786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Qiu M, Constable RT. In vivo method for correcting transmit/receive nonuniformities with phased array coils. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:666–674. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]