Abstract

We determined the complete nucleotide sequences of the small (S) and medium (M) RNA genome segments of a Kairi virus (KRIV) isolate from the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. The S segment consists of 992 nucleotides, and the M segment consists of 4,619 nucleotides. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted on each genomic segment, and these data are discussed. A 526 nucleotide region of the large (L) segment was also sequenced. This is the first study to present sequence and phylogenetic data for a KRIV isolate from Latin America.

The family Bunyaviridae is the largest family of arthropodborne viruses and consists of five genera: Orthobunyavirus, Phlebovirus, Hantavirus, Nairovirus, and Tospovirus [11]. The genus Orthobunyavirus is divided into 18 serogroups, including the Bunyamwera (BUN) serogroup. Kairi virus (KRIV) belongs to this serogroup, as do Bunyamwera, Cache Valley and Fort Sherman viruses. KRIV is a poorly characterized virus originally isolated from mosquitoes in Trinidad in 1955 [1] and later isolated from mosquitoes, monkeys and a rodent in Brazil, mosquitoes in Columbia and Mexico, and a febrile horse in Argentina [4, 5, 8, 10]. Antibodies to KRIV were detected in 5% of humans sampled in Argentina in 2004 and 2005 [12]. It is not known if KRIV is associated with human illness.

All viruses in the family Bunyaviridae contain a tripartite, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome [7, 11]. The three RNA segments have been designated as small (S), medium (M), and large (L). All three RNA segments of a virus have the same complementary nucleotide sequences at their 3′ and 5′ termini. Base pairing of these terminal sequences results in the formation of panhandle structures that may serve as transcriptase-recognition structures. The genome encodes four structural proteins and a variable number of nonstructural proteins, depending on the genus. Two nonstructural proteins are encoded by the Orthobunyavirus genome. The S segment codes the nucleocapsid protein (N) and a nonstructural protein NSS in overlapping reading frames. The M RNA segment codes for a polyprotein that is post-translationally processed to yield two glycoproteins (Gn and Gc) and a nonstructural protein NSM. The L RNA segment codes for the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). There is a limited amount of sequence data for KRIV. The complete S RNA segment for the prototype KRIV (strain TRVL-8900) has been sequenced, and almost all of the M RNA segment and a 587-nt region of the L RNA segment of TRVL-8900 have also been sequenced (GenBank accession nos. X73467, EU004186, and EU004191, respectively [2, 6]. There are no sequence data available for any other KRIV strains. The purpose of this study was to sequence the complete S and M RNA segments and part of the L RNA segment of a KRIV isolate (designated KRIV-Mex07) from the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico in 2007 [8].

Primers for the RT-PCR and sequencing of KRIV-Mex07 were designed using the nucleotide sequence data of TRVL-8900. Complementary DNAs were generated using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and PCRs were performed using Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The nucleotide sequences at the extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the S and M RNA segments were determined by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends as described previously [8]. PCR products were purified using a PureLink gel extraction kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced using a 3730×1 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

The complete nucleotide sequences of the S and M RNA segments and part of the nucleotide sequence of the L RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 were determined (GenBank accession nos. EU879063, GQ118699, and GQ118700, respectively). The S RNA segment consists of 992 nucleotides and is 95.0% identical to the S RNA segment of TRVL-8900. 19 of the 21 terminal nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the KRIV-Mex07 S RNA segment are complementary. Exceptions are the A and C at nucleotide positions 9 and 984, respectively, and the G and U at nucleotide positions 19 and 974, respectively (nucleotide numbers correspond to the positive-sense RNA). The same two mismatches are also present at the terminal ends of the TRVL-8900 S RNA segment [6] and the KRIV-Mex07 M RNA segment. The S RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 contains two open reading frames (ORFs). The most 5′ AUG initiates the longest ORF, which encompasses nucleotide positions 82–783 and encodes the N protein. The predicted translation product consists of 233 amino acids and is 97.4% identical and 98.7% similar to the N protein of TRVL-8900. The second ORF encompasses nucleotide positions 104–430 and encodes the NSS protein. The predicted translation product consists of 108 amino acids. KRIV-Mex07 contains a single AUG at the start of this ORF. Most viruses in the BUN serogroup, including TRVL-8900, contain a tandem AUG at the beginning of this ORF. The NSS protein of KRIV-Mex07 is 98.1% identical and 98.1% similar to the NSS protein of TRVL-8900.

The M RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 consists of 4,619 nucleotides and is 93.3% identical to the M RNA segment of TRVL-8900. This alignment revealed that the TRVL-8900 M RNA segment has not been fully sequenced; it is predicted that 19 and 14 nucleotides are missing from the distal 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. A notable difference between the M RNA segments of KRIV-Mex07 and TRVL-8900 is the presence of an 18-nt insertion in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of KRIV-Mex07 at nucleotide positions 141–158. The M RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 contains a single ORF that encodes a polyprotein of 1,437 amino acids that is predicted to yield Gn, Gc and NSM proteins of 286, 865 and 69 amino acids, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences of the Gn proteins of KRIV-Mex07 and TRVL-8900 are 98.6% identical and 99.3% similar, the Gc proteins are 98.0% identical and 99.2% similar, and the NSM proteins are 97.1% identical and 100% similar. Last, a 526-nucleotide fragment of the KRIV-Mex07 L RNA segment was sequenced. Alignment of this nucleotide sequence to the homologous region of TRVL-8900 revealed that these sequences are 93.2% identical. This sequence encodes the first 168 amino acids of the RdRp and is 97.0% identical and 98.8% similar to the homologous region of TRVL-8900.

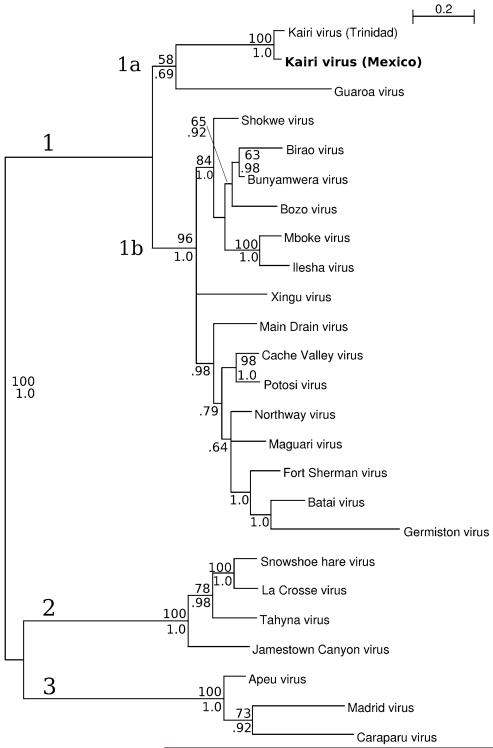

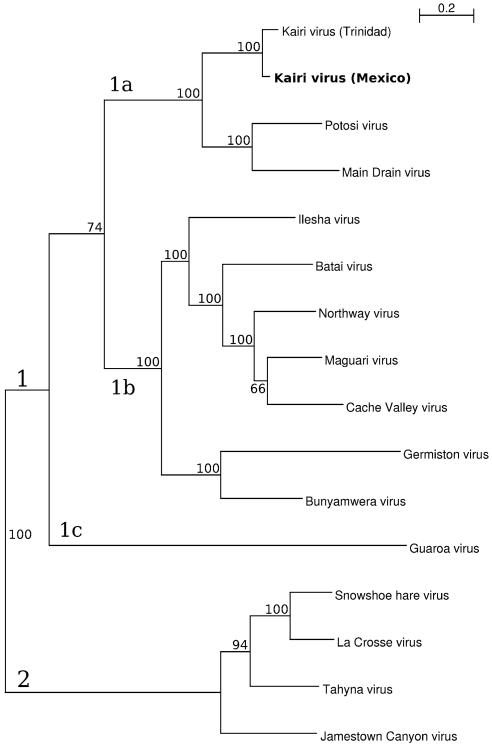

Phylogenetic trees were constructed with Bayesian methods using the entire nucleotide sequences of the S and M RNA segments of KRIV-Mex07 and other selected bunyaviruses (Figs. 1, 2). In the Bayesian tree constructed using S segment sequences, KRIV-Mex07 shares a close phylogenetic relationship with TRVL-8900 (Fig. 1). The bootstrap and posterior support for this topological arrangement are 100% and 1.0, respectively. Phylogenetically, the S segments of these two isolates are most closely related to the homologous region of Guaroa virus (GROV). These three isolates, together with the 15 other members of the BUN serogroup used in the analysis, comprise a distinct clade (denoted as 1). Viruses in the California (CAL) and Group C serogroups comprise clades 2 and 3, respectively. In the Bayesian tree constructed using M segment sequences, two distinct clades (denoted as 1 and 2) were observed (Fig. 2). Clade 1 contains BUN serogroup viruses, and clade 2 contains CAL serogroup viruses. Group C serogroup viruses were not included in the analysis because none have had their complete M RNA segment sequenced. Clade 1 further separates into three nested clades (1a, 1b and 1c). KRIV-Mex07 and TRVL-8900, together with Potosi virus (POTV) and Main Drain virus (MDV), comprise clade 1a. The bootstrap and posterior supports for this clade are 100% and 1.0, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the S RNA segment of a Kairi virus isolate from Mexico (KRIV-Mex07). The displayed phylogeny was estimated by using the program MRBAYES, version 3.1 [9]. The phylogenetic analysis is based on the complete S RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 and 23 other bunyavirus isolates. All branches are labeled with bootstrap support (out of 100) above and posterior support below. Bootstrap support is based on maximum-likelihood analysis using Phyml as described previously [8]. An unrooted tree was inferred but is shown rooted using the midpoint method. Support values for the rooting branch are shown at the far left. KRIV-Mex07 is denoted in bold

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the M RNA segment of a Kairi virus isolate from Mexico (KRIV-Mex07). The displayed phylogeny was estimated by using the program MRBAYES, version 3.1 [9]. The phylogenetic analysis is based on the complete M RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 and 15 other bunyavirus isolates. All branches are labeled with bootstrap support (out of 100) above. Bootstrap support is based on maximum-likelihood analysis using Phyml as described previously [8]. Posterior support was 1.0 on every branch and is not shown. KRIV-Mex07 is denoted in bold

The relative phylogenetic positions of the S and M RNA segments of most viruses are similar. Two exceptions are POTV and MDV; both viruses have a close phylogenetic relationship to KRIV in the tree constructed using M RNA segment sequences, but their phylogenetic relationship is closer to Cache Valley virus when S RNA segment sequences are used. These findings are consistent with earlier reports that POTV and MDV are natural reassortants that acquired their M RNA segments from another BUN serogroup virus [3]. The distribution of the S and M RNA segments of GROV also differs; it is most closely related to KRIV in the tree constructed using S RNA segment sequences but is almost genetically equidistant to BUN and CAL serogroup viruses when M RNA segment data are used. These findings are consistent with other bunyavirus phylogenetic studies [2, 6].

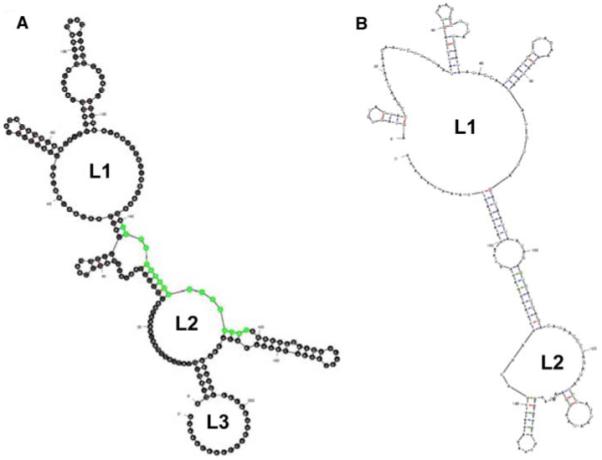

As noted earlier, the M RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 contains a 18-nt region in its 5′UTR that is absent in the corresponding 5′UTR of TRVL-8900. These two regions and the first 100-nt of their respective ORFs were analyzed using the Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction [13]. One representative suboptimal structure for each 5′ UTR is presented (Fig. 3). This analysis revealed that the 5′ UTRs of the Mex07 and TRVL-8900 M RNA segments could fold into considerably different secondary structures. One common feature of both 5′ UTRs is that they are predicted to form two large (>20-nt) interior loops (denoted as L1 and L2), between which is a long stem structure containing a smaller interior loop. However, the 5′ UTR of the Mex07 M RNA segment contains a large (24 to 36-nt) hairpin loop (L3) that is absence for the corresponding region of TRVL-8900 M RNA segment.

Fig. 3.

Potential secondary structures located in the 5′ UTRs of the KRIV-Mex07 and TRVL-8900 M RNA segments as predicted by MFOLD version 3.0 [13]. One of the four suboptimal structures is shown for KRIV-Mex07 (a), and one of the seven suboptimal structures is shown for TRVL-8900 (b). The first 100-nt of the corresponding ORFs were also used in the analysis. Both 5′ UTRs are predicted to form two large (>20-nt) interior loops (denoted as L1 and L2). The 5′ UTR of the Mex07 M RNA segment was also predicted to form a large (24 to 36-nt) hairpin loop (denoted as L3). Green indicates extra sequence present in KRIV-Mex07

In summary, the complete S and M RNA genome segments of a KRIV isolate from Mexico were sequenced. Sequence data are available for one other KRIV isolate, TRVL-8900, which was collected in Trinidad more than 50 years prior. One notable genetic difference between these isolates is that the M RNA segment of KRIV-Mex07 contains an 18-nt insertion in its 5′UTR. As a consequence of this insertion, differences in the secondary structures of the 5′UTRs of the KRIV-Mex07 and TRVL-8900 M RNA segments are predicted to occur. Additional research is needed to ascertain whether this insertion has an effect on the phenotype of KRIV.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant 5R21A I067281-02 from the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Victor Soto, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA.

Karin S. Dorman, Department of Genetics, Development and Cell Biology, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA

W. Allen Miller, Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA.

Jose A. Farfan-Ale, Laboratorio de Arbovirologia, The Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico

Maria A. Loroño-Pino, Laboratorio de Arbovirologia, The Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico

Julian E. Garcia-Rejon, Laboratorio de Arbovirologia, The Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico

Bradley J. Blitvich, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA

References

- 1.Anderson CR, Aitken TH, Spence LP, Downs WG. Kairi virus, a new virus from Trinidadian forest mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1960;9:70–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1960.9.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briese T, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI. Analysis of the medium (M) segment sequence of Guaroa virus and its comparison to other orthobunyaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3071–3077. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briese T, Kapoor V, Lipkin WI. Natural M-segment reassortment in Potosi and Main Drain viruses: implications for the evolution of orthobunyaviruses. Arch Virol. 2007;152:2237–2247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calisher CH, Oro JG, Lord RD, Sabattini MS, Karabatsos N. Kairi virus identified from a febrile horse in Argentina. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:519–521. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Causey OR, Causey CE, Maroja OM, Macedo DG. The isolation of arthropod-borne viruses, including members of two hitherto undescribed serological groups, in the Amazon region of Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961;10:227–249. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1961.10.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn EF, Pritlove DC, Elliott RM. The S RNA genome segments of Batai, Cache Valley, Guaroa, Kairi, Lumbo, Main Drain and Northway bunyaviruses: sequence determination and analysis. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:597–608. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-3-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott RM. Molecular biology of the Bunyaviridae. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:501–522. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-3-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farfan-Ale JA, Lorono-Pino MA, Garcia-Rejon JE, Hovav E, Powers AM, Lin M, Dorman KS, Platt KB, Bartholomay LC, Soto V, Beaty BJ, Lanciotti RS, Blitvich BJ. Detection of RNA from a Novel West Nile-like virus and high prevalence of an insect-specific flavivirus in mosquitoes in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:85–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanmartin C, Mackenzie RB, Trapido H, Barreto P, Mullenax CH, Gutierrez E, Lesmes C. Venezuelan equine encephalitis in Colombia, 1967. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1973;74:108–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmaljohn CS, Nichol ST. Bunyaviridae. In: Knipe DM, editor. Fields virology. 5th edn. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1741–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tauro LB, Almeida FL, Contigiani MS. First detection of human infection by Cache Valley and Kairi viruses (Orthobunyavirus) in Argentina. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:197–199. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]