Abstract

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) in patients with a large fibroid burden is controversial. Anecdotal reports describe serious complications and limited clinical results. We report the long-term clinical and magnetic resonance (MR) results in a large series of women with a dominant fibroid of >10 cm and/or an uterine volume of >700 cm3. Seventy-one consecutive patients (mean age, 42.5 years; median, 40 years; range, 25–52 years) with a large fibroid burden were treated by UAE between August 2000 and April 2005. Volume reduction and infarction rate of dominant fibroid and uterus were assessed by comparing the baseline and latest follow-up MRIs. Patients were clinically followed at various time intervals after UAE with standardized questionnaires. There were no serious complications of UAE. During a mean follow-up of 48 months (median, 59 months; range, 6–106 months), 10 of 71 patients (14%) had a hysterectomy. Mean volume reduction of the fibroid and uterus was 44 and 43%. Mean infarction rate of the fibroid and overall fibroid infarction rate was 86 and 87%. In the vast majority of patients there was a substantial improvement of symptoms. Clinical results were similar in patients with a dominant fibroid >10 cm and in patients with large uterine volumes by diffuse fibroid disease. In conclusion, our results indicate that the risk of serious complications after UAE in patients with a large fibroid burden is not increased. Moreover, clinical long-term results are as good as in other patients who are treated with UAE. Therefore, a large fibroid burden should not be considered a contraindication for UAE.

Keywords: Fibroids, Embolization, Uterus

Introduction

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is an accepted alternative to surgery in the management of symptomatic patients with uterine fibroids [1–7]. However, the role of UAE in symptomatic women with a large fibroid burden is subject to debate. In several small studies, response to UAE was judged insufficient in patients with a large fibroid, >8 cm, with a higher rate of need for additional therapy after UAE [8, 9]. In addition, there is general unspecified fear of an excessive effect after embolization in these patients due to rapid ischemia and necrosis. This fear is based on several early case reports describing rare but serious complications shortly after UAE for large fibroids, such as unbearable pain, infection, septic uterine necrosis, and lethal sepsis [10–12]. On the other hand, some studies suggest that results of UAE in patients with a large fibroid burden are as good as in other patients with symptomatic fibroids, with comparable low rates of serious complications [13–15]. However, long-term follow-up studies in this special subset of patients have not been performed to date.

In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the long-term results of UAE in symptomatic women with a large fibroid burden.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, with a waiver for informed consent. From an institutional database with prospectively collected data on 431 women with symptomatic uterine fibroids treated with UAE between August 2000 and April 2005, 71 consecutive women were selected with a large fibroid burden, defined as a dominant fibroid with a longest axis >10 cm and/or a uterine volume of >700 cm3. Diagnosis of uterine fibroid disease was established by history, clinical gynecological examination, and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI). All women had previous medical therapies for their complaints without sufficient clinical results. Exclusion criteria for UAE were pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, gynecological malignancy, pure adenomyosis, and thin-stemmed pedunculated fibroids.

All 71 women were premenopausal, with a mean age of 42.5 years (median, 40 years; range, 25–52 years). Presenting symptoms of 71 women were bleeding in 60 (85%), pain in 41 (58%), and bulk-related symptoms in 64 (90%). Of 71 women, 42 (59%) had a fibroid >10 cm, and 30 of these 42 women had an overall uterus volume of >700 cm3. The remaining 29 women (41%) had a uterus volume of >700 cm3 but no fibroid larger than 10 cm.

Patients were categorized into three subgroups: group A, patients with a dominant fibroid diameter of >10 cm and a uterine volume of <700 cm3 (>10 cm, <700 cm3); group B, patients with a dominant fibroid of >10 cm and an uterine volume of >700 cm3 (>10 cm, >700 cm3); and group C, patients with a uterine volume of >700 cm3 and with fibroids smaller than 10 cm (<10 cm, >700 cm3). Presenting symptoms of the subgroups of patients are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presenting symptoms of 71 patients with a large fibroid burden in three subgroups

| Group | Bleeding | Pain | Bulk-related symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 12): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 9 | 6 | 11 |

| B (N = 30): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 25 | 16 | 26 |

| C (N = 29): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 26 | 19 | 27 |

| All (N = 71) | 60 | 41 | 64 |

MRI at Baseline and Follow-up

All patients had native and contrast-enhanced MRI prior to embolization and at various intervals postembolization. From baseline MRI, the dimensions and volumes of the fibroids and uterus were assessed. Volume calculation was done using the formula of a prolate ellipse (length × depth × width × 0.5233). Dominant fibroid infarction rate and overall fibroid infarction rate after UAE were assessed by two observers in consensus on the latest MRI by visual estimation of a decrease in enhancement compared to the baseline MRI as described by Siskin [16]. Infarction of <80% was considered insufficient.

Embolization Procedure

UAE was performed after selective catheterization of both uterine arteries via a unilateral approach. The use of a microcatheter was left to the discretion of the physician. In women who desired future pregnancy, embolization was performed simultaneously on both sides to limit radiation exposure. Various embolic agents (Contour SE, EmboGold, Bead Block, and Embosphere Microspheres) ranging in size from 500 to 900 μm were used. The end point was complete occlusion of arteries to the perifibroid plexus, with sluggish flow in the ascending segment of the uterine artery, leaving the main uterine artery, cervico-vaginal branches, and uteroovarian anastomoses patent [17]. Complications were recorded.

Clinical Follow-up

Baseline clinical status was assessed by an interview using a standardized questionnaire on patient’s symptoms of bleeding, pain, and bulk. At various time intervals after UAE patients returned for a follow-up MRI and an interview by a nurse practitioner to assess the evolution of symptoms using the same questionnaire. For the purposes of this study, in July 2009 all women were requested to fill out the validated Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life questionnaire (UFS-QOL) [18]. In addition, women were asked to fill out the standardized questionnaire, aiming at the long-term evolution of their baseline symptoms, additional therapy, and adverse events such as vaginal dryness and discharge, menopausal complaints, or fibroid expulsion. In women who did not return the questionnaire of July 2009, data of the latest previously available follow-up interval were considered the final result.

Data Analysis

Complications are expressed as a proportion. The fibroid diameter change during follow-up and the rate of uterine volume reduction were assessed for all patients and the three subgroups by comparison of the latest MRI with baseline. Volume reduction of large fibroid and uterus was calculated as a proportion of the initial volume. Differences in volume reduction of dominant fibroid and uterus and differences in infarction rates were evaluated among the three subgroups. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of proportions, and t-test for comparison of means. p-Values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was done with MedCalc statistical software (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Imaging Results

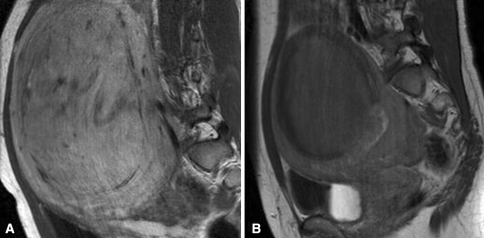

Mean MRI follow-up was 13.8 months (median, 12 months; range, 4–47 months). The dominant fibroid diameter and volume reduction, uterine volume reduction, and infarction rates of the dominant fibroid and overall fibroid infarction rate for all patients and the three subgroups are reported in Table 2, and a representative image is shown in Fig. 1. After UAE, mean infarction rates of both the dominant fibroid and the overall fibroid infarction rate were high (85–90%) in all three subgroups. On an individual basis, in 20 of 71 patients (28%) the infarction rate was considered insufficient, at <80%. One patient had recurrent symptoms without additional therapy, and eight patients had good clinical results despite the insufficient infarction rate. The remaining 11 patients had additional therapy during follow-up.

Table 2.

Baseline of 71 patients and follow-up MR findings of 70 patients with a large fibroid burden treated with uterine artery embolization, including results per subgroup

| Group | Dominant fibroid diameter (cm; mean and range) | Dominant fibroid diameter reduction (%) | Dominant fibroid volume (cm3; mean and range) | Dominant fibroid volume reduction (%) | Uterine volume (cm3; mean and range) | Uterine volume reduction (%) | Fibroid infarction rate (mean and range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Dominant | Overall | ||||

| A (N = 12): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 10.6 | 7.7 | 27 | 379 | 177 | 53 | 591 | 385 | 35 | 90% | 80% |

| 10–13 | 6.4–9.5 | 297–547 | 68–254 | 471–691 | 225–621 | 40–100% | 50–100% | ||||

| B (N = 30): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 12.6 | 9.4 | 25 | 723 | 353 | 51 | 1358 | 760 | 44 | 85% | 85% |

| 10–16 | 6.0–13.4 | 417–1265 | 79–1127 | 788–3037 | 134–1796 | 20–100% | 20–100% | ||||

| C (N = 29): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 18 | 199 | 131 | 34 | 1105 | 20 | 45 | 90% | 90% |

| 4.3–9.6 | 3.4–9.6 | 42–424 | 18–343 | 653–1855 | 58–1526 | 40–100% | 50–100% | ||||

| All (N = 71) | 10.3 | 8 | 22 | 450 | 233 | 44 | 1125 | 639 | 43 | 86% | 87% |

| 4.3–16 | 3.4–13.4 | 42–1265 | 18–1127 | 471–3037 | 58–1796 | 20–100% | 20–100% | ||||

Fig. 1.

Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI in a 31-year woman. After embolization, the fibroid is completely infarcted with a volume reduction of 60%

Adverse Events

Adverse events were reported by 21 patients (29.5%). Transient amenorrhea occurred in five women, and permanent amenorrhea in another five (one 43-year-old woman and four women older than 47 years). One woman reported a fibroid expulsion 2 months after UAE, three reported fibroid sloughing, and two had vaginal discharge. Three women needed additional pain medication. Three women developed an unspecified urogenital infection, successfully treated with antibiotics. None of the patients developed severe postembolic syndrome. There was no emergency surgery after UAE.

Additional Therapy During the Follow-up

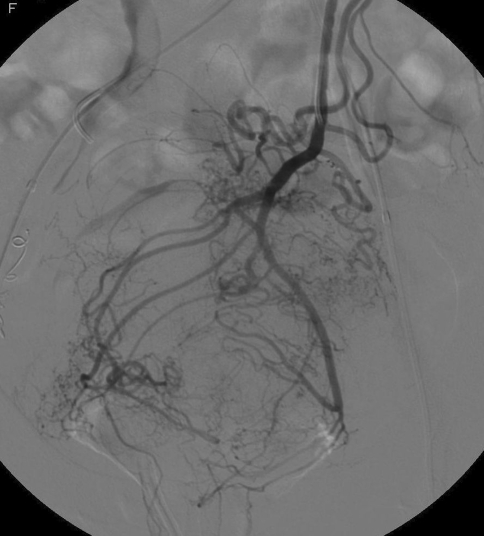

During a mean follow-up of 48 months (median, 59 months; range, 6–106 months), 18 of 71 patients (25%) underwent additional therapy. The distribution of patients with additional therapy in the three subgroups is reported in Table 3. Eight women had a second embolization. In six of eight women fibroids were initially completely devascularized but showed revascularization on later MRI. In the other two women the fibroids were initially not completely devascularized due to additional vascular supply from the ovarian artery and the inferior mesenteric artery (Fig. 2); this was corrected in the repeat embolization. After repeat UAE all fibroids remained devascularized on subsequent MRI.

Table 3.

Additional therapy after uterine artery embolization (UAE) during mean follow-up of 48 months in 71 patients with a large fibroid burden and in the three subgroups

| Group | Additional UAE | Hysterectomy | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 12): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 1 | 2 | 3 (25%) |

| B (N = 30): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 4 | 5 | 9 (30%) |

| C (N = 29): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 3 | 3 | 6 (21%) |

| All (N = 71) | 8 | 10 | 18 (25%) |

Fig. 2.

Angiogram 14 months after insufficient result of first embolization in a 44-year-old woman with a large fibroid burden demonstrates a substantial additional vascular supply to the uterus from the inferior mesenteric artery, not appreciated at first embolization

Ten women had a hysterectomy due to insufficient relief of clinical symptoms. In one patient, with fever and vaginal discharge, a hysterectomy was performed early, at 7 weeks after UAE. Pathological examination showed normal uterine stroma, without signs of necrosis. In one patient hysterectomy was performed after recurrence of symptoms 4 years after UAE.

Evolution of Presenting Symptoms

The late follow-up questionnaire in July 2009 was returned by 44 of 71 patients (62%) and these patients had a mean follow-up duration of 68 months (median, 73 months; range, 48–106 months). Of these 44 patients, 13 had additional therapies and were censored from final follow-up. The long-term evolution of symptoms in the remaining 31 patients is reported in Table 4. The second part of the questionnaire, the UFS-QOL was filled out by 35 of the 44 patients: 7 patients had a hysterectomy, 1 a second embolization, and 1 patient was menopausal at the age of 54, 6 years after UAE. Results are reported in Table 5. After UAE the symptom severity score and the health-related quality-of-life (HRQL) total score of our patient group are within the range of normal women; scores for the other subscales are in the range of mildly symptomatic patients.

Table 4.

Long-term clinical follow-up results after a mean of 68 months in 31 patients treated with uterine artery embolization for a large fibroid burden who returned the late questionnaire and had no additional therapy

| Group | Bleeding (no. improved) | Pain (no. improved) | Bulk-related symptoms (no. improved) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 6): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 4 of 4 | 3 of 3 | 6 of 6 |

| B (N = 13): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 11 of 11 | 6 of 6 | 13 of 13 |

| C (N = 12): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 4 of 4 | 3 of 3 | 6 of 6 |

| All (N = 31) | 19 of 19 | 12 of 12 | 25 of 25 |

Table 5.

Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life questionnaire after a mean of 68 months in 35 patients treated with uterine artery embolization for a large fibroid burden who returned the late questionnaire and had no additional therapy

| Group | Symptom severity | Concern | Activities | Energy mood | Control | Self-conscious | Sexual function | HRQL total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 7): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 17.4 | 78.6 | 75 | 69.9 | 72.9 | 78.6 | 58.9 | 86.6 |

| B (N = 16): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 12.1 | 62.6 | 66.9 | 84.8 | 66.3 | 59.5 | 65 | 84.6 |

| C (N = 12): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 22.5 | 87.3 | 94.2 | 95.8 | 94.1 | 91.7 | 81.8 | 92.5 |

| All (N = 35) | 16.6 | 72.1 | 75.4 | 82.8 | 74.7 | 72.1 | 67.3 | 87.7 |

Of the 71 patients, 27 patients did not return the long-term questionnaire and had a shorter mean follow-up, of 14 months (median, 12 months; range, 6–40 months). In 5 of 27 patients additional therapies were performed. Evolution of symptoms of the remaining 22 women is reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Clinical follow-up after a mean of 14 months in 22 patients treated with uterine artery embolization for a large fibroid burden who did not return the late questionnaire and had no additional therapy

| Group | Bleeding | Pain | Bulk-related symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 3): >10 cm, <700 cm3 | 3 of 3 improved | 1 of 1 improved | 2 of 2 improved |

| B (N = 8): >10 cm, >700 cm3 | 5 of 6 improved | 1 of 3 improved | 5 of 6 improved |

| 1 of 6 unchanged | 2 of 3 unchanged | 1 of 6 unchanged | |

| C (N = 11): <10 cm, >700 cm3 | 7 of 8 improved | 9 of 10 improved | 8 of 10 improved |

| 1 of 8 unchanged | 1 of 10 unchanged | 2 of 10 unchanged |

Data Analysis

Statistical evaluation of the differences in dominant fibroid volume reduction, uterine volume reduction, and infarction rates among the three subgroups did not show significant results.

Discussion

UAE is, at present, gaining acceptance as an alternative to hysterectomy or myomectomy in symptomatic women with uterine fibroids. Many women appreciate the results that can be obtained with UAE: improvement or elimination of symptoms and reduction of uterine size, with maintenance of the uterus and preservation of fertility. In many studies the good long-term results and low complication rates of this treatment have been reported [5–7]. Despite these overall satisfying results, in the subgroup of patients with a large fibroid burden, a higher rate of serious ischemic, necrotic, and infectious complications is ascribed, based on several anecdotal reports [9–11].

Our results show that a large fibroid burden does not decrease the efficacy of UAE and there is no higher complication rate. Our results in patients with a large fibroid burden are comparable and in the same range as in large studies reporting on results of UAE in unselected patients [6, 7]. In the vast majority of our patients there is a significant volume reduction of the fibroids in combination with good clinical results.

The rate of adverse events after UAE in patients with a large fibroid burden was very low, and emergent surgery was never necessary. These results are valid for patients with a very large dominant fibroid, as well as for patients with a large uterine volume from many smaller fibroids or the combination. During long-term follow-up, the frequency of additional embolization and hysterectomy in our selected patients was in the same range as in previous studies on unselected patients [6]. Our findings suggest that, in women with a large fibroid burden who are reluctant to undergo hysterectomy, UAE is a valuable alternative with a high rate of success in preserving the uterus.

Our study has several limitations. Long-term clinical follow-up was not available for all patients. The UFS-QOL was assessed only at long-term follow-up, and not at baseline. However, strong points of our study were the follow-up duration of more than 5 years in the majority of patients and the complete clinical follow-up in terms of additional treatments.

Our study is the first on UAE in patients with a large fibroid burden in a large patient group and with long-term follow-up. Several studies on limited patient groups and with a shorter follow-up have reported good results similar to ours [13, 14].

Some authors consider a large fibroid burden a risk factor for serious complications such as infections and ischemic uterine injury requiring emergent hysterectomy, and it is advocated that UAE should not be performed for multiple fibroids >10 cm in diameter or a large uterine volume. However, the presumption to refrain from UAE in these patients is based on a few early case reports describing serious complications [9, 11]. Katsumori was the first to report on results of UAE in 47 patients with large fibroids as part of a cohort of 152 patients with a mean follow-up of 17 months [19]. The conclusion of that study was that there was no increased risk to patients undergoing UAE for fibroids on the basis of size. Later, these good results were confirmed in a smaller study with the limited follow-up of 12 months [13].

In conclusion, our results confirm previous reports that the risk of serious complications after UAE in patients with large fibroids is not increased. Moreover, clinical long-term results are as good as in other patients with symptomatic fibroids treated with UAE. Therefore, a large fibroid burden should not be considered a contraindication for UAE.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Watson GMT, Walker WJ. Uterine artery embolisation for treatment of symptomatic fibroids in 114 women: reduction of the fibroids and women’s view of the success of the treatment. BJOG. 2002;109:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker WJ, Pelage PJ. Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: clinical results in 400 women with imaging follow up. BJOG. 2002;109:1262–1272. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worthington-Kirsch RL, Popky GL, Hutchins FL. Uterine arterial embolization for the management of leiomyomas: quality-of-life assessment and clinical response. Radiology. 1998;208:625–629. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.3.9722838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spies JB, Bruno J, Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Magee ST, Ascher SA, Jha RC. Long-term outcome of uterine artery embolization of leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5; Pt 1):933–939. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000182582.64088.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin SC, Spies JB, Worthington-Kirsch RL, Peterson E, Pron G, Li S, Myers ER, Fibroid Registry for Outcomes Data (FIBROID) Registry Steering uterine artery embolization for treatment of leiomyomata: long-term outcomes from the FIBROID Registry. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296526.71749.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohle PNM, Voogt M, de Vries J, van Oirschot C, Smeets A, Vervest HAM, Lampmann LEH, Boekkooi PF. Long term outcome of uterine artery embolization in women with symptomatic fibroids. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MD, Lee HS, Lee MH, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Sun HC (2008) Long-term results of symptomatic fibroids treated with uterine artery embolization: in conjunction with MR evaluation. Eur J Radiol (epub ahead of print, Dec 10) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Marret H, Cottier JP, Alonso AM, Giraudeau B, Body G, Herbreteau D. Predictive factors for fibroids recurrence after uterine artery embolisation. BJOG. 2005;112:461–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Fozan H, Tulandi T. Factors affecting early surgical intervention after uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol Surg. 2002;57:810–815. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin SC, McLucas B, Lee M, Chen G, Perrella R, Vedantham S, Muir S, Lai A, Sayre JW, DeLeon M. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata midterm results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/S1051-0443(99)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vashisht A, Studd J, Carey A, Burn P. Fatal septicaemia after fibroid embolisation. Lancet. 1999;354:307–308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02987-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelage JP, Le Dref O, Soyer P, Kardache M, Dahan H, Abitbol M, Merland JJ, Ravina JH, Rymer R. Fibroid-related menorrhagia: treatment with superselective embolization of the uterine arteries and midterm follow-up. Radiology. 2000;215:428–431. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ma11428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prollius A, de Vries C, Loggenberg E, du Plessis A, Nel M, Wessels PH. Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: the effect of the large uterus on outcome. BJOG. 2004;111:239–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirsadraee S, Tuite D, Nicholson A. Uterine artery embolization for ureteric obstruction secondary to fibroids. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2008;31:1094–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firouznia K, Ghanaati H, Sanaati M, Jalali AH, Shakiba M. Uterine artery embolization in 101 cases of uterine fibroids: do size, location, and number of fibroids affect therapeutic success and complications? Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2008;31:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siskin GP, Beck A, Schuster M, Mandato K, Englander M, Herr A. Leiomyoma infarction after uterine artery embolization: a prospective randomized study comparing tris-acryl gelatin microspheres versus polyvinyl alcohol microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampmann LE, Smeets AJ, Lohle PN. Uterine fibroids: targeted embolization, an update on technique. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:128–131. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spies J, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves S. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:290–300. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsumori T, Nakajima K, Mihara T. Is a large fibroid a high-risk factor for uterine artery embolization? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1309–1314. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]