Abstract

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, especially those involving Zn, Al, Zr (Negishi coupling) and B (Suzuki coupling), collectively have brought about “revolutionary” changes in organic synthesis. Thus, two regio- and stereodefined carbon groups generated as R1M (M = Zn, Al, B, Cu, Zr, etc.) and R2X (X = I, Br, OTs, etc.) may now be cross-coupled to give R1–R2 with essentially full retention of all structural features. For alkene syntheses, alkyne elementometalation reactions including hydrometalation (B, Al, Zr, etc.), carbometalation (Cu, Al–Zr, etc.), and haloboration (BX3 where X is Cl, Br, and I) have proven to be critically important. Some representative examples of highly efficient and selective (≥98%) syntheses of di-, tri- and oligoenes containing regio- and stereodefined di- and trisubstituted alkenes of all conceivable types will be discussed with emphasis on those of natural products. Some interesting but undesirable cases involving loss of the initial structural identities of the alkenyl groups are attributable to the formation of allylpalladium species, which must be either tamed or avoided. Some such examples involving the synthesis of 1,3-, 1,4-, and 1,5-dienes will also be discussed.

Introduction

Not long ago, the primary goal of the synthesis of complex natural products and related compounds of biological and medicinal interest was to be able to synthesize them, preferably before anyone else. While this still remains as a very important goal, a number of today's top-notch synthetic chemists must feel and even think that, given ample resources and time, they are capable of synthesizing virtually all natural products and many analogues thereof. Accepting this notion, what would then be the major goals of organic synthesis in the twenty-first century? One thing appears to be unmistakably certain. Namely, we will always need, perhaps increasingly so with time, the uniquely creative field of synthetic organic and organometallic chemistry for preparing both new and existing organic compounds for the benefit and well-being of the mankind. It then seems reasonably clear that, in addition to the question of what compounds to synthesize, that of how best to synthesize them will become increasingly more important. As some may have said, the primary goal would then shift from aiming to be the first to synthesize a given compound to seeking its ultimately satisfactory or “the last synthesis”.*

If one carefully goes over various aspects of the organic synthetic methodology, one would soon note how primitive and limited it had been until rather recently or perhaps even today. For the sake of argument, we may propose here that the ultimate goal of organic synthesis would be “to be able to synthesize any desired and fundamentally synthesizable organic compounds (a) in high yields, (b) efficiently (in as few steps as possible, for example), (c) selectively preferably all in ≥98-99% selectivity, (d) economically, and (e) safely, abbreviated hereafter as the y(es)2 manner.”

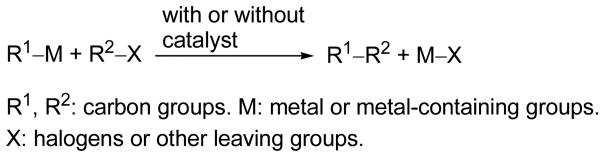

As an argumentative but heavy-handed Ph.D. student at the University of Pennsylvania, the senior author of this article was struck by a number of roundabout processes involved in well-known and important reactions, such as acetoacetic ester synthesis and malonic ester synthesis. “Why not devising more straightforward ways for the formation of all important C– C bonds?” This indeed was the starting point, if no more than a dream at that point, of his pursuit of C–C cross-coupling defined as shown in Scheme 1 and affectionately nicknamed LEGO game approach to synthesis. If any R1 and R2 groups, same or different, could be coupled in the y(es)2 manner, most, if not all, of the synthetic tasks would be reduced to that of preparing fragmentary and simpler precursors, R1M and R2X. Moreover, this straightforward “retrosynthetic” fragmentation can be repeated as many times as needed.

Scheme 1.

Half-a-century ago, however, only a limited number of cases of cross-coupling reactions using Grignard reagents and related organoalkali metals containing Li, Na, K, and so on were known. Their reactions with sterically less hindered primary and some secondary alkyl electrophiles (R2X) are generally satisfactory. Even so, the overall scope of their cross-coupling reactions was severely limited. One of their most serious limitations was their inability to undergo satisfactory C–C bond formation with unsaturated R2X containing unsaturated carbon groups, such as aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl groups, with some exceptions1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scope and Limitations of Uncatalyzed Cross-Coupling with Grignard Reagents and Organoalkali Metals

|

Note: Cu-promoted and Cu-catalyzed reactions have provided some satisfactory procedures. Conventional wisdom: Avoid cross-coupling! But, should we?

Evolution of the Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling

The cross-coupling methodology has evolved mainly over the past four decades into one of the most widely applicable methods for C–C bond formation in the y(es)2 manner, that is centered around the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling with organometals containing Al, Zn, Zr (Negishi coupling),2, 3 B (Suzuki coupling),2, 4 and Sn (Stille coupling)2, 5 as well as those containing several other metals including Cu,6 In,7 Mg,8 Mn,9 and Si10 (Hiyama coupling). Although of considerably more limited scope, both the seminal nature of the Ni-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling of Tamao and Kumada11a, 11b as well as of Corriu11c and its sustained practical synthetic values must not be overlooked in cases where its overall synthetic merits are comparable with or even superior to those Pd-catalyzed reactions mentioned above.

In this article where alkenylation, briefly supplemented with alkynylation, is the main topic, attention will be mainly focused on the Pd-catalyzed version of the Negishi coupling and Suzuki coupling with those metals displaying superior features in their hydrometalation (B, Zr, and Al), carbometalation (Al and Zr), and halometalation (B), as well as Zn which generally offers the most favorable overall profile featuring (i) arguably the highest intrinsic reactivity under Pd-catalyzed conditions leading to generally high product yields, (ii) high turnover numbers (TONs hereafter) often exceeding a million,12 (iii) nearly perfect (≥98%) retention of stereo- and regiochemical details in most cases, (iv) surprisingly favorable chemoselectivity, and (v) general absence of recognized inherent toxicity. It should be added that Zn salts can also serve as effective cocatalysts or promoters13 accelerating other Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions involving Al,13 Zr,13 B,14 Cu,6 Sn,15 and so on.

Evolutions within the authors' group actually began with the development of some selective C–C bond formation reactions of alkenylboranes leading to most probably the earliest highly selective (≥98%) syntheses of unsymmetrically substituted conjugated (E, E)- and (E, Z)-dienes16, following the pioneering studies of alkyne hydroboration by Brown17 and subsequent C–C bond formation by Zweifel18 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Despite these successes, however, the authors' group concurrently began exploring the possibility of promoting the C–C bond formation with alkenylboranes and alkenylborates with some transition metals. After a series of total failures with some obvious choices then, namely a couple of cuprous halides, which were later shown to be rather impure, our attention was turned to a seminal publication of Tamao reporting the Ni-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling (Tamao-Kumada-Corriu coupling).11 Our quixotic plans for substituting Grignard reagents with alkenylboranes and alkenylborates were uniformly unsuccessful.19 In retrospect, it must have been primarily due to the fact that all of our experiments were run at 25 °C in THF. As soon as we replaced alkenylboron reagents with alkenylalanes, however, smooth Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of (E)-1-alkenyldiisobutylalanes with several aryl bromides and iodides took place to provide the cross-coupling products of ≥99% E geometry.19a The corresponding Pd-catalyzed reactions were also observed but no apparent advantage in the use of Pd(PPh3)4 in place of Ni(PPh3)4 was noticed. As can be surmised from our preceding studies shown in Scheme 2, one of our main goals was to be able to synthesize stereo- and regio-defined conjugated dienes. Indeed, both Ni- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling of alkenylalanes with alkenyl iodides proceeded as desired.19b In these reactions, however, the Pd-catalyzed reactions, were distinctly superior to the corresponding Ni-catalyzed reactions in that the Pd-catalyzed reactions retained the original alkenyl geometry to the extent of ≥97%, mostly >99%, where the corresponding Ni-catalyzed reactions showed the formation of undesirable stereoisomers up to 10%.19b Our literature survey revealed that there was one paper by Murahashi8a reporting 4 cases of the Pd-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling in 1975. We later learned that two other contemporaneous papers by Ishikawa8c and Fauvarque8d published in 1976 also reported examples of the Pd-catalyzed variants of the Ni-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling. With our two papers published in 1976,19 we thus reported, for the first time, Ni- and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of non-Grignard reagents, namely organoalanes. Significantly, some unmistakable advantages associated with Pd over Ni was also recognized for the first time.19b

Sensing that the major player in the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling might be Pd rather than the stoichiometric quantity of a metal countercation (M) and that the main role of M of R1M in Scheme 1 might be to effectively feed R1 to Pd, ten or so metals were screened by using readily preparable 1-heptynylmetals containing them. As summarized in Table 2,3a, 20 we not only confirmed our earlier finding that Zn was highly effective8e but also found that B and Sn were nearly as effective as Zn, even though their reactions were much slower. We then learned that examples of Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling with allyltins by Kosugi5b had been reported a year earlier 1977 but that the reaction of the borate marked the discovery of the Pd-catalyzed organoboron cross-coupling. As is well known, extensive investigations of the Pd-catalyzed organometals containing B and Sn began in 1979.4c, 4d, 5c, 5d

Table 2.

Reactions of 1-Heptynylmetals with o-Tolyl Iodide in the Presence of Cl2Pd(PPh3)2 and iBu2AlH

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | temp (°C) | time (h) | product yield (%) | starting material (%) |

| Li | 25 | 1 | trace | 88 |

| Li | 25 | 24 | 3 | 80 |

| MgBr | 25 | 24 | 49 | 33 |

| ZnCl | 25 | 1 | 91 | 8 |

| HgCl | 25 | 1 | trace | 92 |

| HgCl | reflux | 6 | trace | 88 |

| BBu3Li | 25 | 3 | 10 | 76 |

| BBu3Li | reflux | 1 | 92 | 5 |

| AliBu2 | 25 | 3 | 49 | 46 |

| AlBu3Li | 25 | 3 | 4 | 80 |

| AlBu3Li | reflux | 1 | 38 | 10 |

| SiMe3 | reflux | 1 | trace | 94 |

| SnBu3 | 25 | 6 | 83 | 6 |

| ZrCp2Cl | 25 | 1 | 0 | 91 |

| ZrCp2Cl | reflux | 3 | 0 | 80 |

On the basis of a “three-step” mechanism consisting of (i) oxidative addition of R2X to Pd(0)Ln species, where Ln represents an ensemble of ligands, (ii) transmetalation between R2Pd(II)LnX and R1M, and (iii) reductive elimination of R1R2Pd(II)Ln to give R1R2 (Scheme 3) widely accepted as a reasonable working hypothesis,3-5, 8, 11 we reasoned that, as long as all three microsteps are kinetically accessible, the overall process shown in Scheme 1 would be thermodynamically favored in most cases by the formation of MX. In view of the widely observed approximate relative order of reactivity of common organic halides toward Pd(0) complexes also indicated in Scheme 3, a wide range of Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of aryl, alkenyl, alkynyl, benzyl, allyl, propargyl, and acyl halides and related electrophiles (R2X) as well as R1M containing these carbon groups were further explored. In view of distinctly lower reactivity of alkyl halides including homobenzylic, homoallylic, and homopropargylic electrophiles, the use of alkylmetals as R1M was considered.

Scheme 3.

A couple of dozen papers published by us during the first several years in the 1980s on Pd-catalyzed (i) alkylation with alkylmetals,21 (ii) cross-coupling between aryl, alkenyl, or alkynyl groups and benzyl, allyl, or propargyl groups,22 (iii) the use of heterosubstituted aryl, alkenyl, and other R1M and R2M,21d, 23 as well as acyl halides,24 and (iv) allylation of metal enolates containing B and Zn that are not extra-activated by the second carbonyl group25 amply supported the optimistic notion that the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling might be very widely applicable with respect to R1 and R2 to be cross-coupled.

Current Profile of the Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling

Today, the overall scope of the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling may be shown as summarized in Table 3. Although any scientific progress is evolutionary, comparison of Table 3 with Table 1 does give us an impression that the progresses made in this area have been rather revolutionary. Regardless, it would represent one of the most widely applicable methods for C–C bond formation that has begun rivaling the Grignard- and organoalkali metal-based conventional methods as a whole for C–C bond formation. Much more importantly, these two, one modern and the other conventional, methods are mostly complementary rather than competitive with each other. As is clear from Table 3, approximately half of the seventy-two classes of cross-coupling listed in Table 3 generally proceed not only in high yields but also in high selectivity (≥98%) in most of the critical respects. As further detailed later, in approximately two dozen other classes of cross-coupling, the reactions generally proceed in high overall yields, but some selectivity features need to be further improved. Only the remaining dozen or so classes of cross-coupling reactions either have remained largely unexplored or require major improvements. Fortunately, in most of these three dozen or so less-than-satisfactory cases, the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling methodology offers satisfactory alternatives requiring modifications as simple as (a) swapping the metal (M) and the leaving group (X), (b) shifting the position of C–C bond formation by one bond, and (c) using masked or protected carbon groups, as exemplified later.

Table 3.

LEGO Game Approach to C–C Bond Formation via Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions

|

At this point, it is useful to briefly discuss some of the fundamentally important factors contributing to the current status of the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling.

(1) Use of metals (M) of moderate electronegativity represented by Zn

The transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling may have started as Grignard or organoalkali metal reactions with organic electrophiles to which transition metal-containing compounds were added in the hope of catalyzing or promoting such reactions. The earlier seemingly exclusive use of Grignard reagents and organoalkali metals as R1M in Scheme 1 strongly suggests that their high intrinsic reactivity was thought to be indispensable. In reality, however, there have been a rather limited number of publications on the reactions of organoalkali metals catalyzed by Pd complexes,8b,26 and the results are mostly disappointing except in some special cases. The current profile of the Pd- or Ni-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling is considerably more favorable.8,11 In the overall sense, however, its scope is significantly more limited than those employing Zn and B supplemented with Al and Zr. It has become increasingly apparent that Grignard reagents and organoalkali metals are intrinsically too reactive for allowing Pd to efficiently participate in the putative three-step catalytic cross-coupling cycle (Scheme 3). Indeed, under the stoichiometric conditions, alkali metals and Mg are often as effective as or even more effective than Zn and other metals.27 These results suggest that their excessive reactivity may serve as Pd-catalyst poisons. Another major difficulty with Grignard reagents and organoalkali metals is their generally low chemoselectivity in the conventional sense. As one of the important advantageous features of the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling is that it permits pre-assembly of functionally elaborated R1M and R2X for the final or nearly final assemblage of R1–R2, the low chemoselectivity of Grignard reagents and organoalkali metals is a critically serious limitation. Despite these shortcomings, however, the Pd- or Ni-catalyzed Grignard cross-coupling8,11 should be given a high priority in cases where it is competitively satisfactory in the overall sense, because Grignard reagents often serve as precursors to other organometals. In the other cases, metals of moderate electronegativity (1.4-1.7), such as Zn (1.6), Al (1.5), In (1.7), and Zr (1.4), where the numbers in parentheses are the Pauling electronegativity values, should offer a combination of superior reactivity under Pd-catalyzed conditions and high chemoselectivity. The surprisingly high chemoselectivity of Zn has made it desirable to prepare organozincs without going through organoalkali metals or Grignard reagents, and intensive explorations by Knochel28 are particularly noteworthy. Although B in boranes may be highly electronegative (2.0) rendering organoboranes rather non-nucleophilic, its electronegativity can be substantially lowered through borate formation. This dual character of B makes it an attractive metal in the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling.4

(2) Pd as the optimal catalyst component

Although Cu,29 Ni,11,13,19,30 Fe,31 and even some other d-block transition metals have been shown to be useful elements in C–C cross-coupling, it is Pd that represents the currently most widely useful catalyst in catalytic cross-coupling. In a nutshell, it shares with other transition metals some of the crucially important features, such as ability to readily interact with non-polar π-bonds, such as alkenes, alkynes, and arenes, leading to facile, selective, and often reversible oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination shown in Scheme 3 and discussed later in some detail.

In contrast with the high reactivity of proximally π-bonded organic halides, most of the traditionally important heteroatom-containing functional groups, such as various carbonyl derivatives except acyl halides, are much less reactive toward Pd, and their presence is readily tolerated. These non-conventional reactivity profiles associated with some d-block transition metals have indeed provided a series of new and general synthetic paradigms involving transition metal catalysts, such as Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling and olefin metathesis.32

But, why is Pd so well suited for the transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling? If we compare Pd with the other two members of the Ni triad, the heavier and larger Pt is also capable of participating in the three microsteps in Scheme 3, but R1R2PtLn are much more stable than the corresponding Pd- or Ni-containing ones, and their reductive elimination is generally too slow to be synthetically useful, even though fundamentally very interesting.33 On the other hand, smaller Ni appears to be fundamentally more reactive and versatile than Pd. Whereas Pd appears to strongly favor the 0 and +2 oxidation states separated by two electrons, Ni appears to be more prone to undergoing one-electron transferring redox processes in addition to the desired two electron redox processes, leading to less clean and more complex processes. Our recent comparisons of the TONs of various classes of Ni- and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions between two unsaturated carbon groups12,34 have indicated that the Ni-catalyzed reactions generally display lower TONs by a factor of ≥102 and lower levels of retention of stereo- and regiochemical details, readily offsetting advantages stemming from the lower cost of Ni relative to Pd. On the other hand, cleaner Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions often display TONs of ≥106. In some cases, TONs reaching or even surpassing 109 have been observed.34 Thus, for example, the reactions of phenylzinc bromide with p-iodotoluene and of (E)-1-decenylzinc bromide with iodobenzene in the presence of Cl2Pd(DPEphos) in THF exhibited TONs of 9.7×109 and 8.0×107, respectively, while producing the desired products in ≥97% and 80% yields, respectively.34 At these levels, not only the cost issues but also some alleged Pd-related toxicity issues should become significantly less serious.

(3) Critical comparison of R1M and R1H

It is generally considered that the use of R1H in place of R1M would represent a step in the right direction toward “green” chemistry. This statement would be correct and significant provided that all of the other things and factors are equal or comparable. In reality, however, the other things and factors are rarely equal or comparable, and valid comparisons must be made by taking into consideration all significant factors. In Pd-catalyzed alkenylation and also alkynylation, development of Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling versions using Zn, B, Sn, and others as M in R1M were, in fact, preceded by the R1H versions, namely Heck alkenylation35 and Heck-Sonogashira alkynylation.36 Thus, evolution of the cross-coupling version took place in the R1H-to-R1M, rather than R1M-to-R1H, direction. Despite some inherent advantages associated with the R1H versions over the corresponding R1M versions, the synthetic scopes of the R1H versions are generally more limited than the R1M versions, as briefly summarized below.37 Such differences must be clearly delineated for potential users of these reactions. At the same time, efforts to continuously expand the scopes of satisfactory protocols for all available synthetic options must be made. Clearly, most, if not all, of the good and viable synthetic methods are complementary with each other, and synergistic development and applications would be highly desirable. To this end, however, it is critically needed to delineate the scope and limitations of all available satisfactory reactions for given synthetic tasks. From the perspective of synthesizing conjugated di- and oligoenes in the y(es)2 manner, the following difficulties and limitations of Heck alkenylation must be noted.

need for certain activated and relatively unhindered alkenes, such as styrenes and carbonyl-conjugated alkenes, for satisfactory results,38

inability to produce either pure (≥98%) E or Z isomer from a given alkene used as R1H which can be readily and fully overcome by the use of stereo-defined isomerically pure (≥98%) alkenylmetals as R1M,39

frequent formation of undesirable regioisomeric and stereoisomeric mixtures of alkenes35,39 leading to lower yields of the desired alkenes, and

lower catalyst TONs (typically ≤102-103) except for the syntheses of styrenes having an additional aryl, carbonyl, or proximal heterofunctional group35c as compared with those often exceeding 106 for the corresponding R1M version, especially with Zn as M,34 significantly affecting cost and safety factors.

Both fundamental and practical merits of using metals (M) as (a) regio- and stereo-specifiers, (b) kinetic activators, and (c) thermodynamic promoters are abundantly clear, and these differences must not be overlooked. Of course, in those specific cases where the R–H versions of alkenylation and alkynylation are more satisfactory than the R1M version in the overall sense including all y(es)2 factors, their use over the R1M versions may be well justified. Thus, it would still remain important and practically useful to continuously seek and develop additional R1H processes that would proceed in the y(es)2 manner and would be considered superior to the R1M version for a given synthetic task. After all, when one specific chemical transformation is desired, it is the best optimal process for that case rather than the process of the widest scope and general superiority, that is to be chosen.

(4) Advantage associated with the two-stage (LEGO game) processes of the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling

In the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling, the step of the final molecular assembly involves formation of a C–C single bond. As long as it proceeds with full retention of all structural details of the R1 and R2 groups of R1M and R2X, an isomerically pure single product (R1–R2) would be obtained except in those cases where formation of atropisomers are possible.** Furthermore, the preparation of R1M and R2X can be performed in totally separate steps by using any known methods and, for that matter, any satisfactory methods yet to be developed in the future as well. Significantly, a wide range of R1M and R2X containing “sensitive” functional groups in a conventional sense, such as amides, esters, carboxylic acids, ketones, and even aldehydes, may be prepared and directly cross-coupled, as eloquently demonstrated by both regio- and chemoselective preparation and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling of a wide range of aryl and related compounds, notably by Knochel28 and Snieckus.41

As such, the two-stage processes for the synthesis of R1–R2 offer certain distinct advantages over other widely used processes in which some critical structural features, such as chiral asymmetric carbon centers and geometrically defined C=C bonds, are to be established in the very steps of skeletal construction of the entire molecular framework. Such processes include an ensemble of conventional carbonyl addition and condensation (olefination) reactions as well as modern olefin metathesis.32 For example, synthesis of (Z)-alkenes by intermolecular cross-metathesis has just made its critical first step42 towards becoming a generally satisfactory route to (Z)-alkenes in the y(es)2 manner.

(5) Why d-block transition metals? Some fundamental and useful structural as well as mechanistic considerations

The three-step mechanistic hypothesis shown in Scheme 3 has provided reasonable bases not only for understanding various aspects of the seemingly concerted Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling but also for making useful predictions for exploring various types of concerted Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Of course, what is shown in Scheme 3, which evolved from those seminal studies with Ni,11,43 may be applicable to other transition metal-catalyzed processes. At the same time, it is important to be reminded that few mechanistic schemes have ever been firmly established and that they are, in most cases, not much more than useful working hypotheses for rational interpretations and predictions on the bases of the numbers of protons, electrons, and neutrons as well as space for accommodating them including orbitals accommodating electrons, which bring yet another fundamentally important factor, namely symmetry. The fundamental significance of the molecular orbital (MO) theory represented by the frontier orbital (HOMO–LUMO) theory of Fukui,44 synergistic bonding of Dewar,45 exemplified by the so-called Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson (DCD) model (Scheme 4), and the orbital symmetry theory of Woodward and Hoffmann46 can never be overemphasized.

Scheme 4.

In the area of C–C cross-coupling in the y(es)2 manner with Pd and other d-block transition metals as the central catalyst components, at least the following two factors must be critically important:

ability to provide simultaneously one or more each of valence-shell empty orbitals serving as LUMOs and filled non-bonding orbitals serving as HOMOs (Scheme 4) and

ability to participate in redox processes occurring simultaneously in both oxidative and reductive directions under one set of reaction conditions in one vessel.

The first of the two is partially shared by singlet carbenes and related species and therefore termed “carbene-like”. With one each of empty and filled non-bonding orbitals, carbenes are known to readily interact with non-polar π-bonds and even with some σ-bonds. The mutually opposite directions of HOMO–LUMO interactions which significantly minimize the effect of activation energy-boosting polarization in each HOMO–LUMO interaction should be firmly recognized. These features readily explain the facile and selective formation of stable π-complexes with d-block transition metals, which is not readily shared by main group elements, such as B and Al, as they cannot readily provide a filled non-bonding orbital together with an empty orbital.

Despite the above-discussed similarity between carbenes and transition metals, there are some critically significant differences between them. Thus, many transition metal-centered “carbene-like” species are not only of surprising thermal stability, even commercially available as chemicals of long shelf-lives at ambient temperatures, e.g., ClRh(PPh3)3 and Cl2Pd(PPh3)2, but also reversibly formed in redox processes permitting high catalyst TONs often exceeding a million or even a billion.12,34 The authors are tempted to call such species “super-carbenoidal”. Significantly, the “super-carbenoidal” properties of d-block transition metals do not end here. In addition to numerous 16-electron species with one valence-shell empty orbital, there are a number of 14-electron species including surprisingly stable and even commercially available ones, such as Pd(tBu3P)2. In the oxidative addition step in Scheme 3, Pd must not only act like singlet carbene to generate π-complexes for binding, it must also interact with the proximal C–X bond with either retention or inversion, presumably in concerted manners, for which the σ-bond version of the synergistic bonding may be envisioned (Scheme 4). For such processes of low activation barriers, an “effective” 14-electron species may be considered to be critically desired. Although the transmetalation step in Scheme 3 is not at all limited to transition metals, the reductive elimination step, for which a concerted microscopic reversal of oxidative addition discussed above appears to be a reasonable and useful working hypothesis, must once again rely on the “super-carbenoidal” transition metals to complete a redox catalyst cycle. Of course, many variants of the mechanism shown in Scheme 3 are conceivable, and they may be useful in dealing with some finer details.

Alkyne Elementometalation–Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Routes to Alkenes

Historical Background of Alkene Syntheses

Before the advent of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation19,47 and alkynylation37 in the 1970s, syntheses of regio- and stereodefined alkenes had been mostly achieved by (a) carbonyl olefination which must proceed via addition–elimination processes, such as Wittig reaction48 and its variants, such as Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction49 and its later modifications including Z-selective Still-Gennari50 and Ando51 versions as well as (b) Peterson olefination52 and its variants including Corey-Schlessinger-Mills methacrylaldehyde synthesis,53 and (c) Julia54 and related olefination reactions. Even today, many of these reactions collectively represent the mainstay of alkene syntheses. From the viewpoint of alkene syntheses in the y(es)2 manner, however, these conventional methods have been associated with various frustrating limitations to be overcome. With the exception of the alkyne addition routes, many of which can proceed in high (≥98%) stereoselectivity, most of the widely used conventional methods including all of the carbonyl olefination reactions mentioned above must involve β-elimination, which fundamentally lacks high (≥98%) stereoselectivity and often tends to be regiochemically capricious as well.

As discussed earlier, the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation is thought to proceed generally via reductive elimination, although some involving the use of relatively non-polar C–M bonds, such as C–B, C–Si, and C–Sn, are known to proceed at least partially via carbometalation–β-elimination. In sharp contrast with β-elimination, reductive elimination, which is predominantly a σ-bond process, can proceed in most cases with full retention of all alkenyl structural details (See later discussions for significant exceptions due to the intermediacy of allylmetals). Moreover, the scope of Pd-catalyzed alkenylation is fundamentally limited only by the availability of the required alkenyl precursors, as either R1M or R2X, and a wide range of methods for their preparation, both known and yet to be developed, may be considered and utilized. As discussed in detail, many of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation reactions have displayed highly favorable results as judged by the y(es)2 criteria. Thus, the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation has evolved since the mid-1970s into arguably the most general and highly selective (≥98%) method of alkene synthesis known to date (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

At this point, it is both useful and important to classify the alkenyl groups, R1 and/or R2 in R1M and/or R2X, into the following ten structural types (Table 4). Since our attention is mainly focused on those cases where both regio- and stereochemical details critically matter, no intentional discussion of Types I and II alkenyl groups is presented. Although Types IX and X trisubstituted alkenyl groups for the syntheses of tetrasubstituted alkenes are of interest to us, those that are acyclic are substantially more scarce than di- and trisubstituted alkenes in nature. Perhaps, in part, for this reason, the methodology for their syntheses is still underdeveloped and therefore will be only briefly discussed.

Table 4.

Classification and Definition of Ten Types of Alkenyl Groups

| Type | Alkenyl Descriptor | Structure | Regiodefined? | Stereodefined? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Vinyl | No | No | |

| II | α-Monosubstituted |  |

Yes | No |

| III | (E)-β-Monosubstituted |  |

Yes | Yes |

| IV | (Z)-β-Monosubstituted |  |

Yes | Yes |

| V | α, β-cis-Disubstituted |  |

Yes | Yes |

| VI | α, β-trans-Disubstituted |  |

Yes | Yes |

| VII | (E)-β, β′-Disubstituteda |  |

Yes | Yes |

| VIII | (Z)-β, β′-Disubstituteda |  |

Yes | Yes |

| IX | (E)-α, β, β′-Trisubstituteda |  |

Yes | Yes |

| X | (Z)-α, β, β′-Trisubstituteda |  |

Yes | Yes |

RL takes a higher priority than RS according to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rule.

In this article, a relatively brief discussion of well-developed methods for the preparation of Types III and IV β-monosubstituted alkenyl derivatives and their use for the syntheses of α,β-disubstituted alkenes will be followed by more detailed discussion of the preparation of Types V-VIII trisubstituted alkenyl derivatives (highlighted in yellow in Table 4) and their use for the syntheses of trisubstituted alkenes. In the syntheses of trisubstituted alkenes via Types V or VI alkenyl derivatives, construction of the monosubstituted end, conveniently termed here the tail and abbreviated as T, is completed first, and the disubstituted end, termed the head and abbreviated as H, is completed in the final Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling step, i.e., T-to-H construction. Those via Types VII or VIII alkenyl groups then involve H-to-T construction (Scheme 6). As examples of those cases where the modes (or directions) of construction are important, the following pair of syntheses of the C7-C16 fragment (2) of the side-chain of scyphostatin (3) may be presented (Scheme 6). In the earlier H-to-T construction,55 4 (Z = TBDPS) was sequentially tosylated, ethynylated, methylaluminated, and subjected to an “SN2” reaction with (S)-EtO2CCH(Me)OTf to give 5 in 34% yield in 3 steps, which was then converted to 2 in 54% yield in three steps or in 18% yield in six linear steps from 4. In the T-to-H construction,56 4 (Z = TBS) was iodinated and cross-coupled with 6 to give 2 just in two steps in 82% yield after deprotection, while the key intermediate 6 was prepared from allyl alcohol in 30% yield over 7 steps.

Scheme 6.

Elementometalation

Addition of element–metal bonds (E–M), where E is H, C, a heteroatom (X), or a metal (M′), to alkynes and alkenes may be collectively termed elementometalation. As long as M is coordinatively unsaturated, providing one or more valence shell empty orbitals, syn-elementometalation should, in principle, be feasible and facile, as suggested by the synergistic bonding scheme involving the bonding and antibonding orbitals of an E–M bond as a HOMO and LUMO pair for interacting with a π*- and π-orbital pair of alkynes and alkenes, as shown in Scheme 7 for hydrometalation, carbometalation, “heterometalation”, and metallometalation. As such, these processes are stoichiometric, and the metals (M and M′) must be reasonably inexpensive. Besides this practically important factor, there are other chemical factors limiting the available choices of M. Thus, the generally high lattice energies of hydrides and other EM′s of alkali metals and alkaline earth metals make it difficult to observe their favorable elementometalation reactions. In reality, B and Al are just about the only two reasonably inexpensive and non-toxic main group metals capable of readily participating in highly satisfactory uncatalyzed elementometalation reactions. Among d-block transition metals, Zr and Cu readily participate in stoichiometric syn-elementometalation reactions and nicely complement B and Al. For cost reasons, Ti, Mn, and Fe are also attractive, but their elementometalation reactions need further explorations. Likewise, transition metal-catalyzed elementometalation reactions of Si, Ge, and Sn are promising,57 but their adoption will have to be fully justified through objective overall comparisons with B, Al, Zr, and Cu. In this article, no specific discussion of alkyne metallometalation is intended.

Scheme 7.

Importantly, the four metals mentioned above are mutually more complementary than competitive. As summarized briefly in Table 5, hydroboration is the broadest in scope and the most highly chemoselective in the “conventional” sense among all currently known alkyne hydrometalation reactions. Although somewhat more limited in scope and chemoselectivity, Zr tends to display the highest regioselectivity. More significantly, its reactivity in the subsequent Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling is considerably higher than that of B. In many cases where Zr works well, it therefore tends to be the metal of choice. Overall, B and Zr are the two best choices for hydrometalation. Difficulties associated with the relatively high cost of commercially available HZrCp2Cl and its relatively short shelf-life have been finally resolved by the development of an operationally simple, economical, clean, and satisfactory reaction of ZrCp2Cl2 with one equivalent of iBu2AlH in THF for generating genuine HZrCp2Cl (Scheme 8).58

Table 5.

Current Profiles of Hydro-, Carbo-, and Halometalation Reactions with B, Zr, Al, and Cu

| syn-Elementometalation | B | Zr | Al | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| syn-Hydrometalation (Types III-VI) |

|

|

|

|

| syn-Carbometalation (Types VII&VIII) |

|

|

|

|

| syn-Halometalation (Types VII&VIII) |

|

|

|

|

Scheme 8.

In marked contrast, direct and uncatalyzed four-centered carboboration is still essentially unknown. This may tentatively be attributed to the very short, sterically hindered C–B bond. Currently, alkylcoppers61 appear to be the only class of organometals that undergo satisfactory uncatalyzed, stoichiometric, and controlled single-stage carbometalation with alkynes. Although trialkylaluminums do react with terminal alkynes at elevated temperatures, it is complicated by terminal alumination.62 This difficulty was overcome for the single-most important case of alkyne methylalumination through the discovery and development of the Zr-catalyzed methylalumination of alkynes with Me3Al (ZMA reaction).13a,63,64 Ethyl- and higher alkylaluminums64,65 as well as those containing allyl and benzyl groups66 react readily but display disappointingly low regioselectivity ranges due mainly to intervention of cyclic carbozirconation,65 which must be further improved.

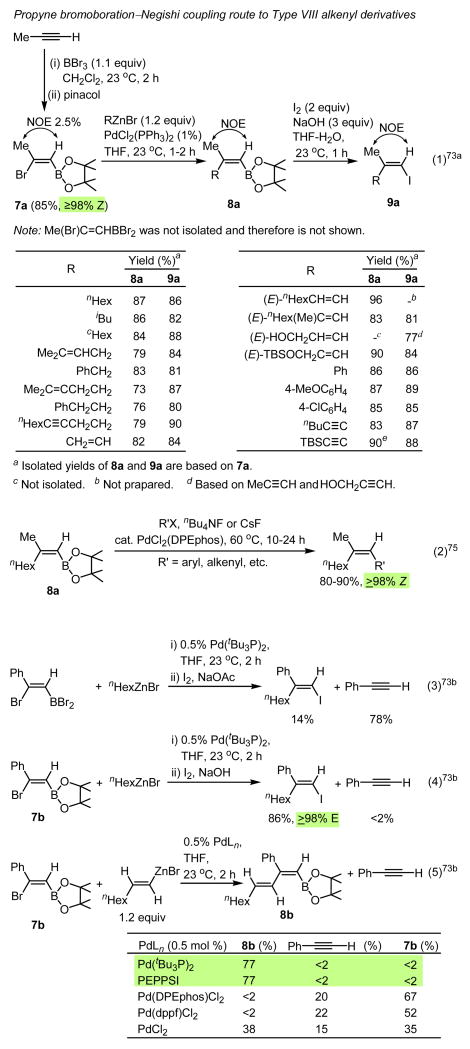

In view of the above-mentioned limitations associated with carbometalation reactions, alkyne haloboration reactions discovered by Lappert67 in the early 1960s and developed by Suzuki68 in the 1980s are of considerable interest. In particular, the alkyne bromoboration–Negishi couping tandem process69 promised to provide a broadly applicable method for the head-to-tail (H-to-T) construction of various types of trisubstituted alkenes (Scheme 9). In reality, however, there were a number of undesirable limitations, of which the following were some of the most critical:

Scheme 9.

formation of (E)-β-haloethenylboranes through essentially full stereoisomerization,70

partial stereoisomerization (≥10%) in the arguably single-most important case of propyne haloboration,71

competitive and extensive β-dehaloboration to give the starting alkynes in cases where 1-alkynes contain unsaturated aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl groups.

sluggish second Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions under the reported Suzuki coupling conditions.69 To avoid this difficulty, use of the second Negishi coupling via B→I72-74 and even B→I→Li74 transformations have been reported as more satisfactory, if circuitous, alternatives.

Although no investigation of the item (i) has been attempted, highly satisfactory procedures have been developed for fully avoiding the difficulty described in the item (ii)73a (Eq. 1, Scheme 9) and substantially improving the second-stage Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling by the direct use of alkenylborane intermediates75 (Eq. 2, Scheme 9). Additionally, a major step towards establishment of highly general and satisfactory alkene synthetic methods based on elementometalation–Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling has been taken with recent development of the hitherto unknown arylethyne bromoboration–Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling tandem process74b (Eqs. 4-7, Scheme 9). At present, however, use of conjugated enynes and diynes in place of arylethynes appears to be even more challenging than the cases of arylethynes, and it is currently under investigation.

Even at the current stage, the alkyne elementometalation–Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling tandem processes summarized in Table 5 provide collectively by far the most widely applicable and satisfactory routes to various types of acyclic alkenes.

Alkyne syn-Elementometalation Followed by Stereo- and/or Regioisomerization

(a) syn-Hydroboration of 1-halo-1-alkynes

syn-Hydroboration of internal alkynes tends to give a mixture of two possible regioisomers. In cases where 1-halo-1-alkynes are used as internal alkynes, the reaction is nearly 100% regioselective placing B at the halogen-bound carbon. The resultant (Z)-α-haloalkenylboranes can be used to prepare (i) (Z)-1-alkenylboranes (Type IV),76 (ii) (Z)-α,β-disubstituted alkenylboranes (Type V),79 and (iii) (E)-α,β-disubstituted alkenylboranes (Type VI)77,78 as summarized in Scheme 10.

Scheme 10.

(b) syn-Hydrometalation of 1-metallo-1-alkynes

syn-Hydrozirconation of 1-silyl-1-alkynes80 and 1-boryl-1-alkynes81 gives 1,1-dimetallo-1-alkenes. By taking advantage of the higher reactivity of the C–Zr bond in various reactions, such as protonolysis, iodinolysis, and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling, Types IV and VI alkenylmetals and other derivatives can be obtained, as demonstrated in Scheme 11.82 Many other possibilities await further explorations.

Scheme 11.

(c) syn-Hydroboration of 1-alkynes followed by halogenolysis with either retention or inversion

Hydroboration of 1-alkynes followed by iodinolysis proceeds with retention to give (E)-1-iodoalkenes (Type III) of >99% purity,83 whereas the corresponding brominolysis in the presence of NaOMe in MeOH produces the stereoinverted Z-isomer (Type IV) of >99% purity84 (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12.

(d) syn-Zr-catalyzed carboalumination (ZMA) of proximally heterofunctional alkynes followed by stereoisomerization

The ZMA reaction of homopropargyl alcohol followed by treatment with AlCl3 at 50 °C for several hours provides the corresponding Z isomer.85 Its mono- and diiodo derivatives have proven to be useful Type VIII alkenyl reagents for the synthesis of a variety of Z-alkene-containing terpenoids, as discussed later in detail (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

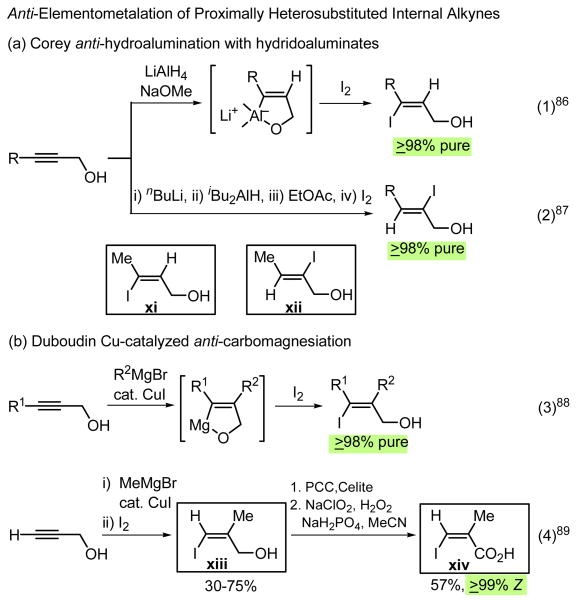

Highly Selective anti-Addition Reactions of Alkynes

The syn-elementometalation reactions of alkynes discussed above may be supplemented with various other addition reactions of alkynes, of which the following two classes of reactions have been particularly useful: (i) anti-hydrometalation and anti-carbometalation reactions of proximally heterosubstituted alkynes, and (ii) conventional anti-addition reactions of alkynes with readily polarizable compounds (X–Y).

(i) anti-Hydrometalation and anti-carbometalation reactions of proximally heterosubstituted alkynes

A fair number of proximally heterosubstituted internal alkynes react with coordinatively saturated metal-containing reagents (E–M) to undergo highly anti-selective (often ≥98% anti) elementometalation reactions. Some representative examples of high synthetic values are shown in Scheme 14.

Scheme 14.

Although the Duboudin anti-carbomagnesiation of propargyl alcohol itself needs to be further improved, this reaction (Eq. 4 in Scheme 14) and the ZMA reaction of propargyl alcohol, which also needs further improvement, can serve as useful synthons, as exemplified by their application in a highly stereoselective synthesis of freelingyne89 (Scheme 15). The Sonogashira90 alkynylation-based Lu-Huang-Ma91 alkynylation–lactonization cascade process was plagued by side reactions, especially alkyne homodimerization. Although not applied to the synthesis of freelingyne, the difficulties associated with this protocol have been resolved by recent development of Negishi alkynylation–Ag-catalyzed lactonization two-step tandem process.37,92

Scheme 15.

(ii) Conventional anti-additions of alkynes of high regio- and/or stereoselectivity

Various polar and readily polarizable halogen-containing reagents (X–Y) are known to add readily to alkynes and alkenes. As long as they are highly (≥98%) regio- and/or stereoselective, they may serve as useful cross-coupling partners, R1M and/or R2X. In the cases of alkene addition, they must also participate in satisfactory elimination reactions. Those di- and triheterofunctional alkenyl reagents i-xxv shown in boxes (Schemes 8 and 13-16) have been widely used as Types III-VIII alkenyl synthons, especially in complex natural product syntheses, as demonstrated throughout this article.

Scheme 16.

Highly (≥98%) Selective and Efficient Syntheses of Dienes, Enynes, and Their Oligomeric Homologues with Emphasis on Those of Biological and Medicinal Interest

In the preceding sections, the basic framework of alkyne elementometalation–Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling route to alkenes in the y(es)2 manner was briefly discussed. In this section, its applications to the syntheses of dienes, enynes and their oligomeric homologues will be discussed with emphasis on those of biological and medicinal interest performed by the authors' group. At this point, it should be reminded that the numbers of possible stereo- and regioisomers of dienes and oligoenes increase exponentially as the degree of oligomerization increases in sharp contrast with oligoynes, as indicated in Table 6 for conjugated dienes. There are more than 50 types of both stereo- and regio-defined conjugated dienes. Gratifyingly, it does appear that, as long as the two required alkenyl groups are obtainable in the y(es)2 manner, Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling, especially under the Negishi and/or Suzuki coupling conditions, will, in the majority of cases, provide the desired dienes also in the y(es)2 manner, as detailed below.

Table 6.

|

Although only the conjugated acyclic diene structures are shown, they may be readily modified to generate the corresponding 1,4- and 1,5-dienes. In this article, no systematic discussion of cyclic structures is intended.

Attention in this article is focused on those 21 dienes (and oligoenic homologues) containing both regio- and stereodefined Types III-VIII alkenyl groups highlighted in yellow.

RL represents a group of higher priority relative to RS according to Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rule.

(1) Conjugated Dienes, Enynes, and Their Oligomeric Homologues Containing One or More Types III and/or IV Alkenyl Groups

As mostly discussed earlier, Type III alkenyl derivatives, i.e., (E)-R1CH=CHM(or X), are widely and satisfactorily generated by:

alkyne hydrometalation (M = B, Zr or, in some cases, Al, etc.) (Table 5, Scheme 8)

polar addition reactions to generate xvi, xvii, and xx (Scheme 16), and additionally,

anti-bromoboration of ethyne70 followed by Negishi coupling (Eq. 1, Scheme 17)

Scheme 17.

On the other hand, Type IV alkenyl derivatives may be prepared by:

Normant alkylcupration of ethyne61b (Eq. 2, Scheme 17),

Zr-catalyzed alkylalumination of ethyne (Eq. 3, Scheme 17),

syn-hydroboration of 1-halo-1-alkynes followed by hydride-induced inversion of configuration76 (Scheme 10),

hydroboration of 1-alkynes followed by brominolysis (but not iodinolysis) with inversion,84 and

syn-hydrozirconation or syn-hydroalumination of 1-boryl- or 1-silyl-1-alkynes followed by protonolysis of the C-Al or C-Zr bond80, 100, 101 (Eq. 4, Scheme 17).

The methods listed above are by no means intended to be exhaustive, even though most, if not all, of the Types III and IV alkenyl reagents may now be prepared by one or more of them. Some other known routes to them that are by and large either not yet well-developed or not selectively applicable to the syntheses of acyclic unsymmetrically substituted alkenes are not cited here. It should also be mentioned that further explorations and developments in this general area are very desirable.

Critical comparison of Negishi and Suzuki versions of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation, Heck alkenylation, and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) olefination as well as its Still-Gennari and Ando modifications

For rigorous comparison of some of the widely used methods for the syntheses of conjugated dienes and oligoenes, syntheses of the four possible isomers of ethyl undeca-2,4-dienoates (13-16) by (i) Negishi alkenylation (Zr and/or Zn),3 (ii) Suzuki alkenylation,4 (iii) Heck alkenylation,35 (iv) HWE olefination,49 and (v) its Still-Gennari50 or Ando modification51 have been carried out. The choice of the conjugated dienoic esters was dictated by the definition of the carbonyl olefinations, i.e., iv and v, requiring α, β-unsaturated carboxylic acid derivatives. At the outset, it was noted that a report on catalyst optimization for the synthesis of ethyl (2Z,4E)-nona-2,4-dienoates by Suzuki alkenylation4e indicated stereo-scrambling occurring to variable extents, 5-80%, at the α,β-C=C bond (Scheme 18). In contrast, all four possible stereoisomers of ethyl undeca-2,4-dienoates (13-16) were prepared in >98% stereoselectivity by Negishi alkenylation (Scheme 19).39a Moreover, the catalyst turnover number (TON) for the synthesis of the 2Z,4E isomer 15 was shown to be at least 105 by using 0.001 mol% of PEPPSI39a (Pyridine-Enhanced Precatalyst Preparation Stablization and Initiation).102 These favorable results shown in Scheme 19 prompted us to re-investigate the stereoselectivity in the Suzuki alkenylation route to 2,4-dienoic esters, such as 15. Although this study is still ongoing, the use of CsF or nBu4NF (TBAF) as a promoter base promises to provide a widely applicable and highly selective (≥98%) Pd-catalyzed alkenylation route to various types of mono-, di-, and oligoenes.39a Thus, for example, 15 was obtained in 88% yield in ≥98% stereoselectivity. We then noticed in our recent literature survey that, although 2,4-dienoic esters were not prepared, Molander's alkenylation103 with potassium alkenyltrifluoroborates prepared by treatment of alkenylboranes with KHF2 of Vedejs104 would provide selectively in 85-88% yields all four stereoisomers of 9-chloro-1-phenylnona-3,5-dienes. Further details of these seemingly related protocols are under investigation.

Scheme 18.

Scheme 19.

The practically acceptable scope of Heck alkenylation with respect to alkenyl halides is wide, but that with respect to the non-halogenated alkene partner is rather limited, usually requiring proximally π-bonded, e.g., Ar, and/or heterofunctional, groups for satisfactory results.38 Furthermore, in cases where stereo-undefined 1-alkenes (H2C=CHR) are used, only one, namely E, isomer can be obtained as the major product thereby making the other isomer inaccessible via this route. In principle, stereo-defined E or Z XCH=CHR may be used in place of H2C=CHR. However, it has been difficult to attain a high (≥98%) stereoselectivity by using (Z)-BrCH=CHCO2Et, as exemplified in Eq. 3, Scheme 20. This and related cases are currently being further clarified. Furthermore, even in favorable cases of Heck conjugated diene synthesis, the TONs reported in the literature,35e using 70% as the lowest acceptable product yield, have been mostly limited to ≤102-103.

Scheme 20.

By definition, the scope of HWE as well as its Still-Gennari50 and Ando51 modifications are limited to the syntheses of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl derivatives. Within this limitation, HWE reactions are widely applicable and used. Unless there is at least one additional stereo-controlling factor, such as the use of aryl aldehyde, however, the reported stereoselectivity for the preparation of 2,4-dienoate esters has been typically ≤90%.39 Using KN(SiMe3)2 and 18-crown-6 (≥2 equiv),105 Still-Gennari olefination provided ≥98% isomerically pure ethyl (2Z,4E)-hex-2,4-dienoate (17) in 98% yield.39 On the other hand, its capricious behaviors, especially in the syntheses of (2Z,4Z)-5-stannylpenta-2,4-dienoic esters, have also been noted. For such Sn-substituted cases, the Ando version was shown to be better than the Still-Gennari version but still only marginally satisfactory (Scheme 21).105 This reaction has recently been applied to the synthesis of (+)-sorangicin A106 (Scheme 21). Clearly, further methodological development in this area is highly desirable.

Scheme 21.

The current profile of various methods for the syntheses of 1,4-disubstituted conjugated dienes are summarized in Table 7. At present, the Pd-catalyzed Negishi alkenylation is the only method permitting highly (≥98%) stereoselective syntheses of all four possible 2,4-dienoic esters. Furthermore, the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation in general represented by Negishi and Suzuki coupling is the only method that can accommodate a wide variety of carbon groups without requiring carbonyl and other activating groups. Some representative earlier examples of the syntheses of natural products containing 1,4-disubstituted 1,3-dienes are shown in Scheme 21.

Table 7.

Current Scopes of the Conjugated Diene Syntheses by Negishi and Heck Alkenylations as well as by HWE and SG&A Olefinations

| Method |  |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd-cat. cross-coupling (Negishi coupling with Zr or Zn) |

|

|

|

|

| Heck alkenylation |

|

|

|

|

| HWE olefination (Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| SG&A olefination (Still-Gennari and Ando olefination) |

|

|

|

|

A brief exploration for developing Pd-catalyzed Negishi alkenylation–HWE olefination synergy has led to the development of a highly (≥98%) selective and efficient Negishi alkenylation route to the di- and oligoenic phosphonoesters for subsequent HWE olefination. Unfortunately, however, the stereoselectivity in the final HWE olefination step is seldom higher than 90% with alkyl-substituted aldehydes. Especially disappointing is that ≥98% pure (Z)-α,β-alkenyl groups preset by Negishi coupling (Eq. 4, Scheme 22) cannot be retained in the subsequent carbonyl olefination step (Eqs. 5 and 6, Scheme 22). On the contrary, all Pd-catalyzed Negishi alkenylation processes fully (≥98%) retains the preset stereochemistry (Eq. 7, Scheme 22). An exceptionally high (≥98%) stereoselectivity observed in the syntheses of (all-E)- and (6E,10Z)-2′-O-methylmyxalamides D (27 and 28) is a pleasant surprise to be pursued further (Eqs. 8 and 9, Scheme 22). Further clarification of all of the factors affecting the stereoselectivity in HWE olefination appears desirable.

Scheme 22.

Carbonyl olefination (acetylenation)–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation synergy

In the preceding section, the current scope and limitations of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation–carbonyl olefination synergy were discussed. Despite the fact that HWE olefination and its modifications often display ≤90% stereoselectivity, carbonyl olefination reactions as a whole and related carbonyl acetylenation reactions have proven to be indispensable for the synthesis of α-chiral alkenes and di- and oligoenes containing such alkenes. For the syntheses of (all-E)- and (6E, 10Z)-2′-O-methylmyxalamides D shown in Scheme 22, the required ≥98% pure γ-chiral α,β-unsaturated aldehydes were prepared by Corey-Schlessinger-Mills modified (CSM hereafter) Peterson olefination52, 53 and SG-modified HWE olefination,50 respectively. The products of these reactions are also carbonyl compounds, prompting yet another round of carbonyl olefination, i.e., HWE olefination, for completion of the desired syntheses.

For carbonyl olefination–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation synergy, those reactions that permit carbonyl olefination-to-alkenylation cross-over are required. Currently, Corey-Fuchs reaction116 (Eq. 1, Scheme 23) is the most widely used reaction of this class. Although further improvement is desirable, iodomethylenation of Takai117 (Eq. 2, Scheme 23) is promising. 1,1-Dihalo-1-alkenes prepared by Corey-Fuchs reaction may then be stereoselectively converted to di- or trisubstitued alkenes by selective halogen substitution reactions. trans-Selective monosubstitution was adequately developed by earlier workers, notably Tamao118 and Roush,119 while more demanding second substitution either with retention120 or with unexpected and nearly complete (≥97-98%) inversion121 have been satisfactorily developed only recently by the authors' group, as detailed later. Perhaps more widely useful is to convert aldehydes to 1-alkynes. Once 1-alkynes are obtained, they may then be used as the starting compounds for alkyne elementometalation–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation. At present, base-induced elimination of 1,1-dihalo-1-alkenes obtained by Corey-Fuchs reaction116 (Eq. 1, Scheme 23) and Ohira-Bestmann122 modification of Seyferth-Gilbert carbonyl acetylenation123 (Eq. 3, Scheme 23) are two of the most widely used protocols.

Scheme 23.

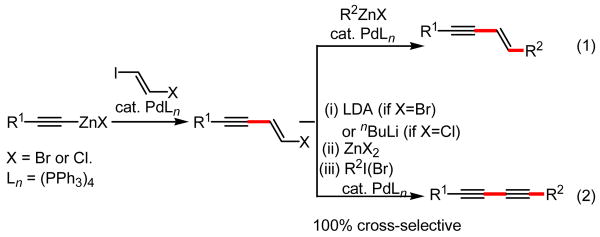

Aside from the synthesis of α-chiral 1-alkynes, 1-alkynes in general for use in alkyne elementometalation–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation are most widely accessible via none other than Pd-catalyzed alkynylation.37 There are two discrete protocols, i.e., (1) Heck-Sonogashira alkynylation discovered in 1975,36 of which the Cu-cocatalyzed Sonogashira version36b may have been more widely used, and (2) Negishi alkynylation discovered in 1977-197820, 124 and its variants.37 Although both are widely applicable and have indeed been widely applied, the currently available data indicate that the Heck-Sonogashira alkynylation is of considerably limited scope, as summarized below and that all of these difficulties can be readily overcome by using Negishi alkynylation (Scheme 24). It is important to note that free terminal alkynes (HC≡CR) are reactive in multiple and rather undisciplined manners, as compared with metalated derivatives (MC≡CR). Thus, ethyne is capable of reacting at both ends, and the second alkynylation tends to be faster (Eq. 1, Scheme 24). When substituted with electron-withdrawing groups, alkynes tend to react as electrophiles, e.g., Michael acceptors, etc. Furthermore, neutral alkynyl groups in free terminal alkynes are far more prone to homo-dimerization than MC≡CR.

Scheme 24.

Noteworthy in Scheme 24 is the use of (E)-1,2-iodobromoethene (xvi) in Eq. 6. As dicussed below, (E)-β-bromoenynes formed as the product can be subjected to the second Pd-catalyzed alkenylation to give a variety of enynes containing Type III alkenyl groups.126 Alternatively, they can be cleanly converted to 1,3-diynylmetals that can be further converted to various 1,3-diynes in a perfectly (100%) cross-selective manner23b, 128 (Scheme 25). For this purpose, however, (E)-1,2-iodochloroethene (xvii) may be preferable to xvi, even though both are satisfactory.

Scheme 25.

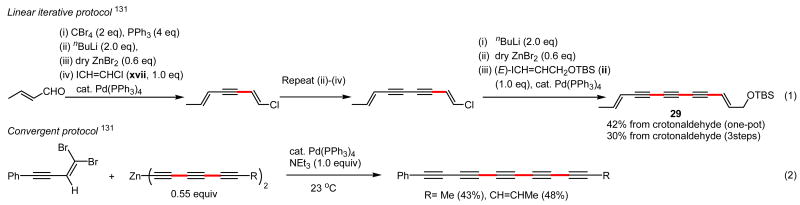

Of various conventional conjugated diyne syntheses, the Cu-catalyzed Cadiot-Chodkiewicz protocol129 has been known for its applicability to the synthesis of unsymmetrical conjugated diynes. In reality, however, its cross-selectivity seldom is very high (≥98% or even ≥95%). Many attempts to develop highly (≥98%) cross-selective Pd-catalyzed alkynyl–alkynyl coupling procedures by the authors' group as well as by others have not yet been very successful, either. However, it now is practically feasible to achieve 100% cross-selective synthesis of a wide range of unsymmetrical conjugated diynes via Pd-catalyzed alkynyl–alkenyl coupling with roughly comparable efforts, as detailed in Scheme 26. Furthermore, the new enyne route can also be applied to highly efficient syntheses of conjugated oligoynes in a linear iterative manner (Eq. 1, Scheme 27), which can even be made partially convergent (Eq. 2, Scheme 27).131 Unfortunately, these exciting conjugated oligo- and poly-ynes have been reported to potentially explosive.132 For this reason, efforts in the authors' group were prematurely terminated, but shorter oligoynes are known to exhibit interesting biological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal, antiinflammatory, antiangiogenic, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and larvicidal activities,133 and their syntheses in the y(es)2 manner, as shown in Schemes 26 and 27, promise to facilitate studies in these areas.

Scheme 26.

Scheme 27.

Although no detailed discussion is intended, conjugated enynes can serve as useful precursors to conjugated dienes containing Type IV alkenyl groups. The alkyne hydroboration–protonolysis protocol of Zweifel18b which has been applied to the stereoselective syntheses of symmetrical (Z,Z)-1,3-dienes18b and unsymmetrical (E,Z)-1,3-dienes16b,c (Scheme 2). With the development of 100% cross-selective route to conjugated diynes, a wide range of unsymmetrical conjugated (Z,Z)-dienes should be accessible in the y(es)2 manner. Perhaps more attractive and satisfactory is to further develop transition metal-catalyzed selective partial hydrogenation of conjugated enynes and diynes in the y(es)2 manner.

It goes without saying that conjugated enynes themselves represent a very important class of natural products, and the Pd-catalyzed alkynyl–alkenyl and alkenyl–alkynyl coupling reactions have provided highly satisfactory routes to them in the y(es)2 manner, as exemplified in Schemes 15 and 28.

Scheme 28.

(2) Conjugated Dienes, Enynes, and Their Oligomeric Homologues Containing One or More Trisubstituted Alkenes

Trisubstituted alkenes are either E or Z. Although a wide variety of synthetic methods are available, the conventional carbonyl olefination and the modern Pd-catalyzed alkenylation appear to be the two representative and widely applicable methods. At present, the former is indispensable for accommodating chiral groups α to C=C bonds. Aside from this critically important aspect, the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation methodology as a whole is comparatively even more advantageous than in the cases of disubstituted alkene synthesis detailed in the preceding section, especially in terms of stereochemical control (≥98%). In cases where carbonyl olefination reactions satisfy the y(es)2 factors, however, they should and will be considered and used.

Of the four types of alkenyl groups highlighted in yellow in Table 4, Types V and VI alkenyl reagents may be used for preparing either E or Z trisubstituted alkenes in the tail-to-head (T-to-H) manner, whereas the stereochemical outcome in their syntheses via Types VII and VIII alkenyl reagents are preset in essentially all known cases. As a brief reminder, the following summary (Table 8) is presented and this summary should also be supplemented with pertinent information presented in Scheme 16.

Table 8.

Summary of Elementometalation Route to Types V-VIII Alkenyl Reagents

| Elementometalation |  |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (Scheme 8, limited) | – | – | – | |

| Yes (Scheme 10) | Yes (Scheme 10) | – | – | |

| Yes | Yes (Scheme 11) | – | – | |

| – | Yes (Scheme 14) | Yes (Scheme 14) | Yes (Scheme 14) | |

| – | – | Yes (Scheme 29) | Yes (Scheme 29) | |

| – | – | Yes (Scheme 13) | Yes (Scheme 13) | |

| – | – | Yes (Scheme 14) | Yes (Scheme 14) | |

| – | – | Yes (Scheme 9) | Yes (Scheme 9) |

Most of the reactions indicated in Table 8 were discussed in some specific details, but a brief discussion of the widely used syn-carbometalation of 1-alkynes is in order at this point.

(a) Zr-catalyzed methylalumination of alkynes (ZMA reaction) and related reactions

The Zr-catalyzed methylalumination of alkynes (ZMA reaction) discovered in 197863 is a genuine bimetallic process requiring both Zr and Al at the crucial moment of carbometalation64,136 (manifestation of the “two is better than one principle”137). The reaction is broad in scope with respect to R1 in the single-most important case of methylalumination. Some other organoaluminum compounds, such as those containing benzyl and allyl, react similarly. Although many other alkylaluminiums also undergo Zr-catalyzed reactions with alkynes, triisoalkylalanes, e.g. iBu3Al, undergo β-H-transfer hydroalumination under otherwise the same conditions,59 while ethyl- and n-alkyl-containing alanes undergo mechanistically highly intriguing Zr-catalyzed cyclic carboalumination.65,138 Both of these reactions must be attributable to favorable β-agostic interaction of alkylzirconium species. It is clearly desirable to overcome these difficulties. In the meantime, however, the ZMA reaction has been applied to the stereoselective syntheses of well over 150 natural products and related compounds as of 2006.3b Some critical aspects of the ZMA reaction are summarized in Scheme 29, and the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation with the alkenylalanes are discussed below.

Scheme 29.

(b) Alkylcupration

The ZMA reaction and alkylcupration are complementary in that ethyl- and higher unhindered alkylcupration proceed readily, although methylcupration is sluggish.61,139 While the products of alkylcupration of ethyne (Type IV) have been used in their Pd-catalyzed alkenylation,6 the corresponding reactions of the Types VII and VIII alkenylcoppers do not appear to have been adequately investigated. Even so, once the alkenylcoppers are converted to alkenyl halides and other derivatives, they will serve as useful Types VII and VIII alkenyl regents.

(c) Haloboration

In view of the brief discussion of the current scope and limitations of alkyne carbometalation presented above, recent development of the alkyne bromoboration–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation protocol, especially those involving the use of propyne73a and arylethynes73b highlighted earlier and summarized in Scheme 9, represents a significant breakthrough in the selective syntheses of Types VII and VIII alkenyl derivatives.

It goes without saying that any additional methods and procedures that satisfy the y(es)2 criteria would contribute to further development of Pd-catalyzed alkenylation methodology. Although somewhat more specialized, those routes to Types V-VIII alkenyl reagents based on hydrometalation (Schemes 8, 10, 11 and 14) and proximal hetero-atom guided carbometalation reactions (Schemes 13 and 14) along with those reagents shown in Scheme 16 have firmly established themselves as important and indispensable parts of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation methodology.

(d) Applications of Types V-VIII alkenyl reagents to the synthesis of natural products containing conjugated di- and oligoenes

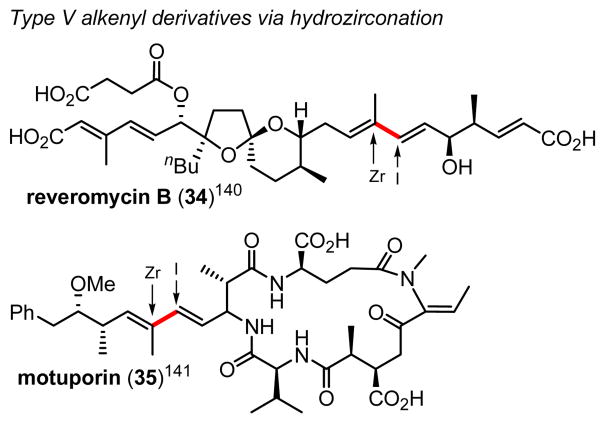

(i) Type V alkenyl derivatives

As indicated in Table 8, Type V alkenyl derivatives are most widely and stereoselectively prepared by syn-hydrometalation of internal alkynes. One generally observed problem is that with internal alkynes with two carbon substituents (R1C≡CR2), the reaction may be of low regioselectivety, unless the two carbon groups are markedly dissimilar. In this respect, hydrozirconation displays two features leading to high regioselectivity levels. One is its ability to undergo facile regioisomerization in the presence of an excess of HZrCp2Cl, and the other is the conversion of proximally O-substituted internal alkynes having a Me group at the other end of the C≡C group with in situ generated HZrCp2Cl+iBu2AlCl·THF (Reagent I) (Eq. 6, Scheme 8). Although limited in scope, these special cases have proven to be of considerable usefulness, as demonstrated in the synthesis of reveromycin B140 and motuporin141 (Scheme 30). More dependable and widely applicable is to resort to syn-hydroboration of 1-halo-1-alkynes followed by Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling (Eq. 3, Scheme 10). Following a promising lead provided by Suzuki,79 this new protocol has been developed in the authors' group,75 and it promises to provide a widely applicable route to Type V alkenyl derivatives.

Scheme 30.

(ii) Type VI alkenyl derivatives

As shown in Scheme 14, anti-hydroalumination of propargylic alcohols provides two kinds of Type VI alkenylaluminum derivatives that can be readily converted to the corresponding iodides of ≥98% Z geometry,86,87 and they have been used for the synthesis of various natural products of terpenoid origin. Potentially more general is the 1-halo-1-alkyne hydroboration–migratory insertion route to Type VI alkenylboranes77,78 (Scheme 10). Although their Pd-catalyzed Suzuki coupling had been problematic,78 their in situ transmetalation to the corresponding Zn derivatives have been shown to readily undergo highly demanding Type VI–Type IV and even Type VI–Type VIII alkenyl–alkenyl coupling, as exemplified by the synthesis of potential intermediates for callystatin A142 and archazolid A or B143,144 (Scheme 31). More recently, a simple and highly satisfactory procedure for direct Suzuki coupling has also been developed in the authors' group, which promises to provide an ultimately satisfactory 1-halo-1-alkyne bromoboration–Negishi–Suzuki coupling tandem protocol.75

Scheme 31.

(iii) Type VII alkenyl derivatives

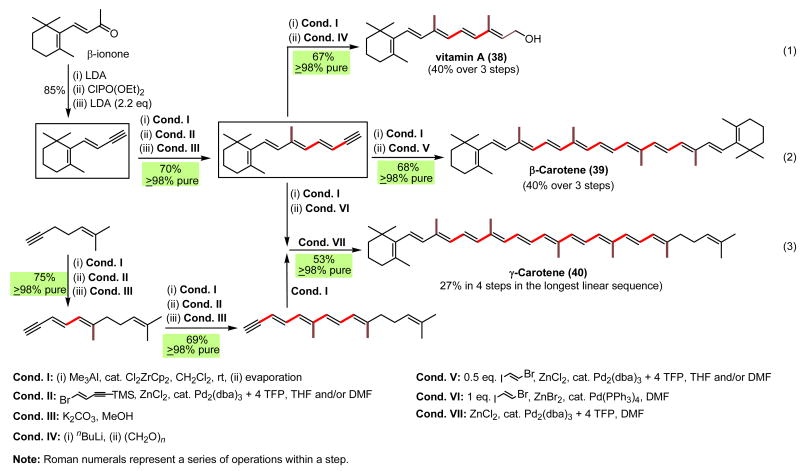

A highly (≥98%) stereoselective synthesis of vitamin A145,146 via alkyne ZMA–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation protocol (Eq. 1, Scheme 32) was followed by exceedingly efficient and selective synthesis of β- and γ-carotenes146 (Eqs. 2 and 3, Scheme 32). In the latter, the use of (E)-ICH=CHBr (xvi) as a 2C linchpin should be noted. Although no rigorous comparisons were attempted, the overall superiority of the Pd-catalyzed alkenylation route over the conventional carbonyl olefination route147 appears to be rather clear.

Scheme 32.

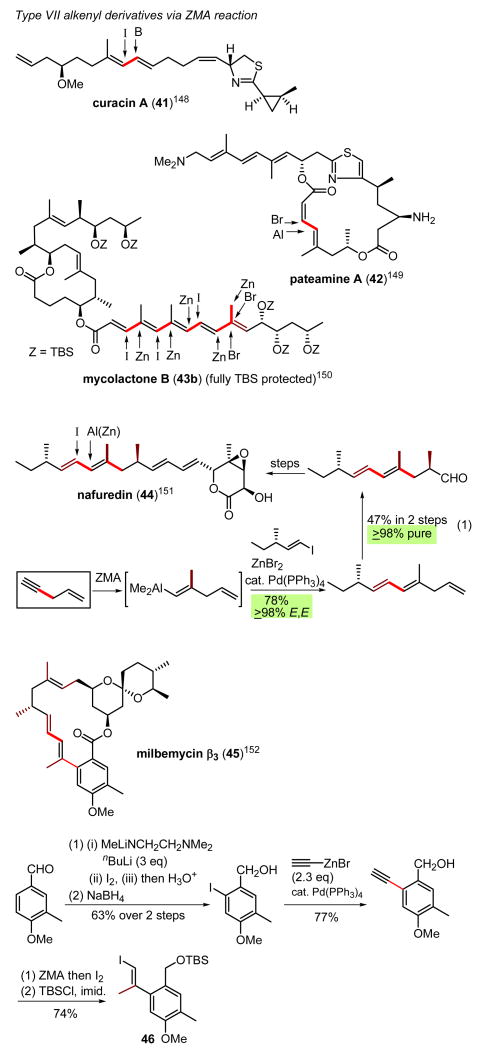

Shown in Scheme 33 are just a few representative examples of the preparation and application of Type VII alkenyl derivatives via ZMA reaction for the synthesis of conjugated di- and oligoenes.148-152 Those examples shown in Eqs. 1 and 2 in Scheme 33 demonstrate the use of 1,4-pentenyne for both ZMA and ZACA reactions in efficient and selective terpenoid syntheses.151,152

Scheme 33.

(iv) Type VIII alkenyl derivatives

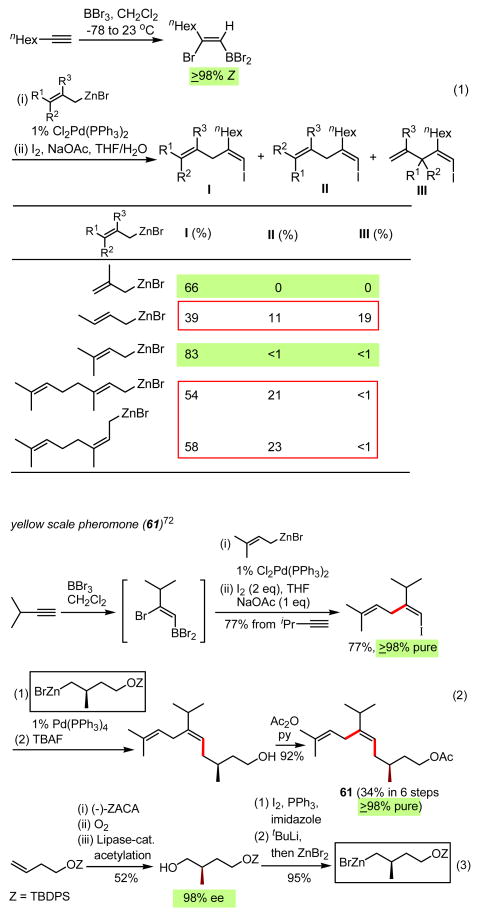

Some of the basic results of the alkyne bromoboration–Pd-catalyzed alkenylation protocol were presented in Scheme 9. Its applications to some natural products syntheses are shown in Scheme 34.

Scheme 34.

In addition to the alkyne elementometalation routes to Types V-VIII alkenyl derivatives, some highly selective alkyne polar addition routes to Types V-VIII alkenyl derivatives, such as xviii, xix, xxiii, and xxv shown in Scheme 16, along with many other Types III and IV alkenyl derivatives, have been shown to be synthetically useful, and their applications are shown throughout this article. Applications of some of the less widely used ones are summarized in Scheme 35.

Scheme 35.

(e) Unexpected stereoisomerization and its prevention in the Pd-catalyzed double substitution of 1,1-dihalo-1-alkenes

“Be aware of capricious allylics! Tame them or avoid them.” Ni- or Pd-catalyzed monosubstitution of 1,1-dihalo-1-alkenes was shown to exhibit surprisingly high (≥98%) trans-stereoselectivity, if a sufficient excess of an organometallic reagent is used to selectively convert the minor cis-monosubstitution product with the faster reacting trans-halogen atom.118,119 This selective monosubstitution has been used widely, notably by Roush,119 for natural products synthesis. Progress in the development of the second substitution was sluggish until a high-yielding and stereoselective reaction proceeding with surprising and nearly full (≥97-98%) stereoinversion121 was discovered (Scheme 36). It was soon found that the use of highly active Pd-catalysts, such as Pd(tBu3P)2 and Pd2(dba)3 used in conjunction with N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs),155 would almost completely (≥98%) suppress stereoinversion mentioned above.120 Thus, other stereoisomers may now be obtained as ≥97-98% pure conjugated dienes.

Scheme 36.

Although precise mechanistic details are still under investigation, 2-bromo-1,3-dienes (51) are simultaneously alkenylic and allylic. Their bulky PdLn-containing derivatives must possess strong desire to acquire the trans-alkenyl geometry (R′ and Pd being trans to each other) on one hand and a good opportunity to do so through reversible allylic rearrangement with inversion. In the second substitution of alkynylated, partial isomerization occurs,121 while the extent of isomerization with arylated derivatives is ≤5%. It should also be noted that, as anticipated, the use of unsaturated groups as R1 can almost completely suppress the stereoisomerization.121

It is gratifying to learn that both processes, one with inversion (Eq. 4, Scheme 36) and the other with retention (Eq. 5, Scheme 36), have been satisfactorily applied to the syntheses of complex natural products (Scheme 37).

Scheme 37.

One of the widely observed limitations in Pd-catalyzed selective substitution of 1,1-dihalo-1-alkenes has been the difficulty in selectively effecting the first trans-selective substitution with an alkyl group. Although this still remains as an important challenge, the first monoalkylation of 1,1-dichloro-1-alkenes with alkylzincs of both RZnX (X=Cl, Br, etc.) and R2Zn type including Me2Zn in DMF in the presence of catalytic amounts of Cl2Pd(DPEphos) has been shown to proceed well to give the desired ≥98% isomerically pure trans-monoalkylated products in 70-90% yields. The second substitution also proceeds in high yields with organomagnesiums containing alkyl, aryl, alkenyl, and allyl groups through the use of highly active catalysts, such as Pd(Cy3P)2162 (Eq. 1, Scheme 38). trans-Selective monoalkylation can proceed well even with 1,1-dibromo-1-alkenes containing certain favorable substituents, such as conjugated Me3SiC≡C group150b (Eq. 2, Scheme 38). It is anticipated that this reaction may be further developed through reaction parameter optimization. It should also be noted that lithiation at -110 °C with tBuLi (2 equiv) of a 2-bromo-1,3-diene derivative shown in Eq. 3, Scheme 38, followed by treatment with CO2 proceeded with full retention of configuration to give the desired carboxylic acid, which was subsequently converted to an antibiotic, lissoclinolide synthesized in 32% overall yield in 9 steps from propargyl alcohol.163

Scheme 38.

(3) 1,4-Dienes via Pd-Catalyzed Alkenyl–Allyl and Allyl–Alkenyl Coupling and 1,4-Enynes via Pd-Catalyzed Alkynyl–Allyl Coupling

Allylic or propargylic organometals containing a coordinatively unsaturated metal can readily undergo facile allyl or propargyl–allenyl rearrangement. In many cases, they may even be considered as resonance hybrids. After all, these rearrangements are nothing more than intramolecular carbometalation processes. As might be predicted from the simple reasoning presented above, the reactions of allylic halides and related derivatives should be more likely to proceed with retention of allylic structural integrity than the corresponding reactions of allylmetals. This generalization has been repeatedly supported by experimental observations.

One of the earliest demonstrations of Pd-catalyzed allylation with ≥98% stereoretention was one-step synthesis of (E)- and (Z)-α-farnesenes in ≥98% selectivety (Eqs. 1 and 2, Scheme 39).22a However, these cases are aided by the fact that geranyl and neryl chlorides are γ,γ-disubstituted allylic derivatives. With γ-monosubstituted allylic derivatives, full stereo- and regiochemical retention has been generally difficult, both stereo- and regio-scrambling occurring typically to the extents of roughly up to 10% (Eq. 3, Scheme 39).22c Nevertheless, it has recently been found that, if the γ-substituent is bulky, e.g., secondary alkyl, clean allylation may be observed (Eq. 4, Scheme 39).150b This favorable δ-branching effect was profitably exploited in recent synthesis of mycolactone core (Eq. 5).150b Although finer details are not clear, applications of the Pd-catalyzed alkenyl–allyl coupling involving the use of B164 and Sn165 shown in Scheme 39 further demonstrate synthetic utility of this reaction.

Scheme 39.

With allylmetals as reagents, the Pd-catalyzed allyl–alkenyl coupling appears to generally produce thermodynamically equilibrated mixtures (Eq. 1, Scheme 40). Nonetheless, in cases when no isomerization is possible, such as allylation with the parent allyl, 2-substituted allyl, and symmetrically γ,γ-disubstituted allyl derivatives, it offers a useful alternative, especially when the complementary alkenyl–allyl coupling is not a viable option, as in the highly efficient and selective synthesis of yellow scale pheromone (61) (Eq. 2, Scheme 40).72

Scheme 40.