Abstract

The photocytotoxicity of a series of anticancer trans-dihydroxido [Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] (X = alkyl or aryl amine) platinum(IV) diazido complexes has been examined and the influence of cis-trans isomerism investigated. A series of photoactivatable PtIV-azido complexes has been synthesized: the synthesis, characterisation and photocytotoxicity of six mixed-ligand ammine/amine PtIV diazido complexes, cis,trans,cis,-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] where X = propylamine (4c), butylamine (5c), pentylamine (6c) and aromatic complexes X= pyridine (7c) 2-methylpyridine (8c), 3-methylpyridine (9c) are reported. Six all-trans isomers have also been studied where X = methylamine (2t), ethylamine (3t), 2-methylpyridine (8t), 4-methylpyridine (10t), 3-methylpyridine (9t) and 2-bromo-3-methylpyridine (11t). All the complexes exhibit intense azide-to-PtIV LMCT bands (ca. 290 nm for trans and ca. 260 nm for cis). When irradiated with UVA light (365 nm) the PtIV complexes undergo photoreduction to PtII species, as monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy. The trans isomers of complexes containing aliphatic or aromatic amines were more photocytotoxic than their cis isomers. One of the cis complexes (9c) was non-photocytotoxic despite undergoing photoreduction. Substitution of NH3 ligands by MeNH2 or EtNH2 results in more potent photocytotoxicity for the all-trans complexes. The complexes were all non-toxic towards human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and A2780 human ovarian cancer cells in the dark, apart from the 3-methylpyridine (9t) 2-bromo-3-methylpyridine (11t) and 4-methylpyridine (10t) derivatives.

Introduction

Cisplatin (cis-[PtIICl2(NH3)2]) is a well-established potent anticancer drug. The mechanism of toxic action of cisplatin has been demonstrated to involve binding of the platinum to guanine residues of nuclear DNA, at the N7 position. The resulting DNA lesions trigger cell death and result in destruction of tumor tissue. Since cisplatin does not discriminate between cancerous and healthy tissue, severe dose-limiting side-effects are a serious problem; as is both intrinsic and acquired resistance to the drug. The handful of Pt drugs currently in the clinic and recent trials show small, yet significant, steps towards addressing these problems, however, there is still much scope for improvement (1).

Inactive drug precursors (prodrugs) can be activated by light, following administration, to create a reactive species specifically where it is required, for example at the tumor site (2). Light-triggered drug release has been investigated for other therapeutic benefits too, e.g. for drugs such as ibuprofen (3,4). Photoactivation of a drug provides a degree of spatial and temporal control over drug dosage, and this strategy is being investigated for a number of metal-based anticancer drugs (5). Photoactive drugs are currently used in the clinic in the modality of photodynamic therapy (PDT), which is an extremely effective treatment for a number of cancers including those of the skin, lung, brain and oesophagus (6,7). The selectivity of PDT that results from the cytotoxic species being produced only where it is required has advantages over other forms of therapy including surgery, chemo- and radiotherapy, in that it can spare the normal tissue and structure of the organ and can be repeated as often as required (2,8). A limitation of PDT is that the cytotoxic mechanism requires oxygen, which can be problematic since tumors are often hypoxic (9). Photochemotherapy which is less dependent on oxygen for the cytotoxic effect is therefore desirable (10). We have previously shown that photoactivation of non-toxic PtIV-azido complexes such as trans,trans,trans-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(py)] can generate potent, cytotoxic species (up to 90× more cytotoxic following irradiation than treatment with cisplatin) capable of causing cell death in a number of cell lines by a mechanism distinct to that of cisplatin (11). PtIV complexes such as these demonstrate good aqueous solubility in comparison to their PtII counterparts, and are much less biologically reactive – a general feature of PtIV complexes (12) – which minimises the potential for side-reactions (and thus the cytotoxicity) of the prodrug on the way to its cellular target.

Time-dependent density functional theoretical (TD-DFT) studies of complexes such as cis,trans,cis-[PtIV(N3)2(OAc)2(bpy)] (bpy = bypyridine) have shown that photoactivation of these PtIV-azido species populates strongly dissociative electronically excited states, which supports the observation that rapid dissociation of the azido ligands – and concomitant reduction to PtII species – is seen following irradiation (13). Although Pt-crosslinking of DNA is subsequently detected, it is still unclear whether this is the main cause of cell death. For trans,trans,trans-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(py)] cell death may occur via a caspase-independent pathway, and is clearly distinct from the molecular changes observed which follow treatment with cisplatin (11). If platinum-based photoactivated chemotherapy (PACT) is not dependent on the presence of oxygen in cells then the system combines the selectivity of PDT with the potency of the platinum cytotoxic agent.

For PtII complexes, the anticancer potential offered by the distinct mechanism of action of trans complexes has been known for some time (14), but only recently has that potential been exploited in depth (15-18), with most research concentrating on cis-Pt complexes. We have previously demonstrated that for photoactivated PtIV–azido complexes both cis- and trans-isomers can show anticancer potential (19). The photodecomposition pathways appear to depend on both the complex and on the environment; 14N NMR spectroscopic experiments monitoring the photodecomposition of cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)2] have demonstrated that in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution, free azide is detected, which does not decompose to N2 gas, whereas if the irradiation is conducted in acidic aqueous solution, no free azide is detected, and instead, O2 is evolved and N2 formed via nitrene intermediates (20).

In this report we discuss the synthesis, characterisation and biological activity of a series of six “cis” dia(m)mine PtIV diazido complexes, with the general formula cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] (X = amine). We also report for the first time the photo and cytotoxicity data for six all-trans complexes of the form trans,trans,trans-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] (X = amine). We have recently reported the syntheses of five of these (21). The ligands attached to the Pt center play a pivotal role in determining the solubility, pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action of a given complex (22), however, until now, structure-activity correlations have not been studied in detail for these systems. Recent work has shown that inclusion of amine ligands such as methylamine (H2NMe) and iPr (isopropylamine) can significantly improve the cytotoxicity of PtII anticancer complexes, thought to be due to slower aquation of the leaving ligands but also likely to be a result of differing stabilities/recognition of the Pt-DNA adducts which are formed (23).Our aim in the present study is to assess the effect of different structural features in a wide range of diazido PtIV complexes incorporating a range of aliphatic and aromatic amines on photoactivity, dark stability, DNA cross-linking and cytotoxicity so as to allow optimization of these features in the design process.

Experimental Procedures

Materials and Methods

K2PtCl4 (Precious Metals Online, Australia), amines, NaN3, AgNO3 and H2O2 (30% solution) were used as received except for 2-methylpyridine, 3-methylpyridine and propylamine which were freshly distilled before use. Syntheses and manipulations of all azido complexes were undertaken under reduced lighting conditions. Positive ion electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) were recorded using a Platform II mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK) or a MAXIS UHR-Qq-TOF (Bruker). Electronic absorption spectra were recorded on a CARY 300 Scan UV-Vis spectrophotometer. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on either Bruker DMX 500 MHz or Bruker AVA 800 MHz spectrometers in (90% H2O/10% D2O), internally referenced to dioxane (δ(1H) 3.76 ppm). Water suppression was achieved by pulse field gradients. 2D TOCSY NMR spectra were recorded using a 20 ms mixing time. Proton assignments for alkylamine CH2 groups are labelled α, β, γ etc. as the groups get progressively further from the Pt, with the α-NH2 directly attached to the Pt.

Irradiation studies were carried out using a UV lamp (2 ×15 W tubes, model VL-215 L; Merck Eurolab, Poole, UK) operating at 365 nm. Samples were irradiated at a distance of 10 cm from the lamp, where the power is 1.5 mW.cm−1, delivering a dose of 10 J.cm−1 over 2 h. Irradiations were monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy (samples irradiated directly in a sealed quartz cuvette). Platinum concentrations required for the calculation of extinction coefficients were determined using an ICP-OES Perkin Elmer Optima 5300 DV Optical Emission Spectrometer equipped with an AS-93 plus autosampler and WinLab32 for ICP (version 3.0.0.0103). Calibrations were achieved using standard Pt solutions (1000 ± 5 ppm, BDH Laboratory Supplies) diluted over the range of 0 – 100 ppm in water, analysed at 265.945 nm and 299.797 nm.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was carried out on an Agilent ChemStation 1200 Series instrument, with a DAD detector. The final concentration used in these samples was ca. 1 mM. For all purity tests, a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 100 Å, 5 μm, Agilent) was used, eluting with 15-95% methanol gradients over varying time intervals with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as an ion-pairing agent and with UV detection at 254 and 210 nm.

Syntheses

Caution! No problems were encountered during this work, however heavy metal azides are known to be shock sensitive detonators, therefore it is essential that any platinum azide compound is handled with care.

Trans complexes trans,trans,trans-[PtIV(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] (where X = MeNH2 {2t}, EtNH2 {3t}, 2-methylpyridine {8t}, 3-methylpyridine {9t} and 4-methylpyridine {10t}) were synthesised as previously reported (21).

Preparation of trans,trans,trans-[PtIV(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(2-bromo,3-methylpyridine)], (11t)

Cisplatin (0.133 g, 0.443 mmol) was suspended in H2O (4 mL) and 2-bromo-3-methylpyridine added (1.328 mmol, 0.148 mL). After refluxing for 4.5 h the solution was cooled to room temperature and HCl (12 mol. eq. 0.443 mL) added. After stirring at 90 °C for 24 h the solution was cooled and placed on ice, the resulting yellow precipitate was filtered off, washed (H2O, EtOH, ether) and dried under vacuum to give trans-[PtCl2(NH3)(2-bromo-3-methylpyridine)] 84.1 mg (41.8 %). Trans-[PtCl2(NH3)(2-bromo,3-methylpyridine)]: 1H NMR (d6-acetone): δ = 8.69 (d, H6, 1J5,6 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, H4, 1J4,5 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, H5, 1H), 3.79 (br s, NH3, 3H), 2.46 (s, CH3, 3H).

Trans-[PtCl2(NH3)(2-bromo-3-methylpyridine)] (37.5 mg, 0.082 mmol) was suspended in H2O (15 mL); DMF (200 μL) and AgNO3 (1.99 mol eq, 27.9 mg) were added. The solution was stirred at 60 °C for 24 h and AgCl was removed by filtration (Whatman, Anotop 10, 0.02 μm). NaN3 (0.82 mmol, 53.3 mg) was added and the suspension stirred for 24 h. The solvent was removed and ice-cold water added, the yellow precipitate was filtered off, washed (H2O, EtOH, ether) and dried under vacuum to give 25.1 mg (65.3 %) of trans-[Pt(N3)2(NH3)(2-bromo,3-methylpyridine)]: 1H NMR (d6-acetone): δ = 8.83 (d, H6, 1J5,6 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, H4, 1J4,5 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (dd, H5, 1H), 3.67 (br s, NH3, 3H), 2.52 (s, CH3, 3H).

19.4 mg (0.050 mmol) of trans-[Pt(N3)2(NH3)(2-bromo-3-methylpyridine)] was suspended in H2O (200 mL) and H2O2 (30%, 0.2 mmol 20.4 μL) added before stirring overnight at room temperature. The volume was reduced to 20 mL and the solution filtered (Whatman, Anotop 10, 0.02 μm). The solvent was removed and acetone was added to precipitate the product, which was collected by filtration and washed with minimal ice cold water, ethanol and diethyl ether, then dried under vacuum to give trans,trans,trans-[PtIV(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(2-bromo,3-methylpyridine)] (11t) (Yield 14.4 mg, 68 %). ESI-MS calculated for [C6H11BrN8O2Pt + Na]+, 523.97, found 524.92. HPLC: 86% purity. 1H NMR (90% H2O/10% D2O): δ = 8.59 (d, Jo,m 6.0 Hz, JHPt 25 Hz, 1H, Hortho), 8.09 (d, Jp,m 7.5 Hz, 1H, Hpara), 7.62 (dd, 1H, Hmeta), 2.59 (s, CH3, 3H). UV-vis: λmax = 287 nm.

Cis complexes

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] complexes (X = PrNH2 {4c}, BuNH2 {5c}, PentNH2 {6c}, py {7c}, 2-methylpyridine {8c}, 3-methylpyridine {9c}).

General method (for individual variations see the relevant compound)

The cis-[PtI2(NH3)(X)] precursors were prepared from the [PtCl3(NH3)]− ion (24); an aqueous solution (8 ml) of KI (3 mmol) and [PtCl3(NH3)]− (1 mmol) was stirred at RT for 30 min to form [PtI3(NH3)]−. The appropriate amine “X” (1.2 mol eq.) was added and the solution was stirred in the dark at RT for 2 h, in accordance with previous methods (25). The resulting yellow solid was filtered, washed (cold H2O) and dried under vacuum before resuspending in minimal H2O. AgNO3 (1.95 mol equiv) was added to the aqueous solution containing cis-[PtI2(NH3)(X)], and the solution was stirred (60 °C, overnight) in the dark. After cooling to RT, AgI was removed by filtration (Whatman, Anotop 10, 0.02 μm) and NaN3 (5 mol eq.) was added to the filtrate which was then stirred in the dark at RT for 4 h. The solution was concentrated and stored overnight at 5 °C, producing a yellow precipitate. Solid [Pt(N3)2(NH3)(X)] was filtered off under suction, washed with ethanol and ether and dried in vacuo for characterisation. The PtII diazido complex was then suspended in water (ca. 40 mL), H2O2 (30%, 10 mol eq.) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 24 h. The solution was concentrated and left at 5 °C overnight. The resulting yellow cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] solid was filtered off, washed (EtOH, ether) and dried in vacuo.

Characterisation of cis complexes

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(propylamine)], (4c)

Propylamine (92 μL, 1.12 mmol) was added to the [PtI3(NH3)]− solution. Yield from [PtI3(NH3)]− (3 steps) 10 mg, 4 %. Crystals of 4c suitable for x-ray diffraction were obtained from an aqueous solution at 4 °C. ESI-MS calculated for [C3H14N8O2Pt + Na]+, 412.1; found 412.2. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C3H14N8O2Pt (389.2): C 9.26, H 3.62, N 28.79; found C 9.87, H 3.69, N 28.12. 1H NMR (90%H2O/10% D2O): δ = 0.95 (t, 3H, γ-CH3), 1.68 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.74 (m, 2H, α-CH2), 5.55 (br s, NH2). UV-Vis (H2O): λmax(ε) = 257 nm (17,500 M−1cm−1).

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(butylamine)], (5c)

NaN3 (20 mol eq.) and H2O2 (20 mol eq.) were used. Yield from [PtI3(NH3)]− (3 steps), 17 mg, 5% . ESI-MS calculated for [C4H16N8O2Pt + K]+, 442.1, found 441.7. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C4H16N8O2Pt (403.30): Calc C 11.91; H 3.99; N 27.78 Found C 12.24, H 3.98, N 27.11.1H NMR (90%H2O/10% D2O): δ = 0.92 (t, 3H, J 8 Hz, δ-CH2), 1.38 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.66 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 2.76 (m, 2H, α-CH2), 5.54 (br s, NH2).UV-Vis (H2O): λmax (ε)= 258 nm (16,000 M−1cm−1).

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(pentylamine)], (6c)

H2O2 (40 mol eq.) was added. (Yield from [PtI3(NH3)]− (3 steps) 98 mg, 25%).ESI-MS calculated for [C5H18N8O2Pt +Na]+, 440.1; found 440.0. 1H NMR (D2O/H2O): δ = 5.54 (br, NH2), 3.02 (NH3), 2.77, (2H, α, CH2) 1.69 (2H, β, CH2), 1.35 (γ/δ, 4H, CH2), 0.89 (CH3, 3H, ε). UV-Vis (H2O): λmax(ε)= 258 nm (15,500 M−1 cm−1).

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(pyridine)], (7c)

For the oxidation, cis-[Pt(N3)2(NH3)(pyridine)] (50 mg) was dissolved in the minimum amount of water (~ 500 mL) and 400 μL of H2O2 (30 % solution) was added. (Yield from [PtI3(NH3)]− (3 steps) 32 mg, 0.08 mmol, 8%). ESI-MS calculated for [C5H10N8O2Pt +Na]+, 432.04, found 431.86.NMR (90%H2O/10% D2O): δ = 7.77 (t, 4H, J 7Hz, Hmeta), 8.23 (t, 2H, J 8Hz, Hpara), 8.68 (d, 4H, JHH 6Hz, JHpt 25 Hz, Hortho). UV-Vis (H2O): λmax (ε)= 258 nm (18,600 M−1 cm−1).

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(2-methylpyridine)] (8c)

(Yield from cisplatin (2 mmol) (4 steps) 58 mg, 0.14 mmol, 7%). ESI-MS calculated for [C6H12N8O2Pt +H]+, 424.08, found 424.2. Calculated for [C6H12N8O2Pt +Na]+, 446.06, found 446.1. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C6H12N8O2Pt (423.3): C 17.02, H 2.86, N 26.47: found C 16.70, H 2.72, N 25.98. 1H NMR (90% H2O/10% D2O): δ = 2.92 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.48 (t, 1H, Ar-H, Hpara) & 7.53 (d, 1H, Ar-H, Hmeta {adjacent to CH3}) overlapping, 8.04 (t, 1H, Hmeta), 8.59 (d, 1H, Ar-H, Hortho). UV-Vis (H O): λmax (ε)= 258 nm (20,000 M−1 cm−1).

cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(3-methylpyridine)], (9c)

The azido complex was made directly from the cis-[PtI2(NH3)(3-methylpyridine)] intermediate using 5 mol eq. NaN3. Yield from [PtI3(NH)3]− (3 steps) 83 mg, 0.19 mmol, 19%).ESI-MS calculated for [C6H12N8O2Pt +Na]+, 446.06, found 446.0. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for PtN8C6O2H12 (423.2): C 17.02, H 2.86, N 26.47: found C 16.66, H 2.35, N 25.53. H NMR (90% H2O/10% D2O): δ = 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.65 (t, 1H, Ar-H, Hmeta), 8.06 (d, 1H, Ar-H, Hpara), 8.47 (d, 1H, Ar-H, Hortho) & 8.51 (s, 1H, Ar-H, Hortho’) (overlapping). UV-Vis (H2O): λmax (ε)= 259 nm (20,000 M−1cm−1).

Irradiations monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy

An aqueous sample (~50 μM) was irradiated directly from above the quartz cuvette and spectra taken at regular intervals between 0 and 120 min. (see Figure S3).

Phototoxicity Studies

Human HaCaT keratinocytes (a kind gift from Professor N. Fusenig, Heidleberg, Germany) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% non-essential amino acids. A2780 human ovarian carcinoma cells and the cisplatin-resistant derivative cell line A2780CIS were maintained in RPMI containing 10% FBS. Cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37 °C in the absence of antibiotics, and were tested regularly for mycoplasma contamination. Test compounds were prepared in Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution (EBSS) and filtered immediately before use. Chlorpromazine (CPZ) was used as the positive control and cell viability of untreated cells +/− UV was >90%. After washing with phosphate buffered salt solution (PBS), cells were treated for 1 h at 37 °C with EBSS containing the test compound. After this time the cells were irradiated by a bank of 2 × 6 ft Cosmolux RA Plus (Cosmedico) 15500/100W light sources (1.77 mW cm−2: λmax 365 nm), filtered to attenuate wavelengths below 320 nm. Irradiance was measured with a Waldmann PUVA meter, calibrated to the source using a double grating spectroradiometer (Bentham, UK). Control cells were treated identically to the test cells and sham irradiated. Phototoxicity was assessed using the neutral red uptake assay as previously described. (19). An IC50 value (the concentration required to inhibit dye uptake by 50%) was determined for each complex using non-linear regression (Graphpad Prism). Goodness of fit was determined from the R2 values of the curves and 95% confidence intervals.

Comet assay

DNA reactivity was assessed using the single cell gel electrophoresis assay as previously described (19, 26).

Results

Chemistry

Synthesis and characterisation of PtIV complexes

The six cis complexes; X = propylamine (4c), butylamine (5c), pentylamine (6c) and aromatic complexes X= pyridine (7c) 2-methylpyridine (8c), 3-methylpyridine (9c) and one all-trans complex trans,trans,trans-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(2-bromo-3-methylpyridine)], (11t) (Table 1) were synthesised via oxidation of the respective cis PtII ammine/amine diazido complexes using adapted literature methods (24,25). The complexes all showed good aqueous solubility. Attempts to synthesise cis PtIV complexes cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)(X)] where X= ethylamine, hexylamine, 2-hydroyethylaminepyridine, and isopropylamine proved unsuccessful: in the case of ethylamine, the PtII precursor cis-[PtII(N3)2(NH3)(EtNH2)] was observed to oxidise spontaneously during synthesis.

Table 1. Structures of complexes discussed in this work.

Spectroscopy

Assignment of alkyl-CH2 groups and overlapping signals in the low-field aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectra of the novel PtIV-azido hydroxido complexes e.g. of 8c and 9c, was aided through the use of 2D TOCSY NMR spectroscopy experiments, since the intensities of TOCSY cross-peaks are related to the number of bonds over which the proton-proton interactions occur. In general for the alkylamine complexes, oxidation of the PtII precursor resulted in deshielding and increased chemical shifts of both the alkyl NH2 resonances (which moved from ca. 4.5 to 5.6 ppm) and the aliphatic protons (e.g. α-CH2 moved from ca. 2.6 to 2.7 ppm). The electronic absorption spectra (H2O) of all new cis complexes are given in Figure S2. These spectra show intense azide-to-metal charge-transfer bands (LMCT) with maxima ranging between 257 –287 nm, with extinction coefficients of 16–20 × 103 M−1 cm−1.

Irradiations with UVA light monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy

For each complex, the intensity of the LMCT band decreased upon exposure to low–power UVA light over a period of 90 min, indicative of photoinduced loss of the azido ligand(s): this was monitored by UV-vis (see Figure S3 for irradiations of the cis complexes {4c-9c}). In the case of 4c, the absorption band decreased in intensity and shifted to a longer wavelength upon irradiation. This band shift was not observed for the other cis complexes.

Photobiology

Photo-cytotoxicity was investigated following UVA irradiation in three cell lines. The methodology used is designed specifically to identify potential human phototoxins using procedures agreed by convention (27). The test compares the effects of the drug alone compared to the drug plus a very low dose of long wave UV irradiation. In this respect it is not the same as a conventional constant challenge cytotoxicity test as the contact time of the photoactivated drug with the target cell is very short (about 60 min). The dose of UVA irradiation used was 5 J cm−2, which is equivalent to approximately 60 minutes exposure or less to midday sunlight (56°N; Dundee, Scotland). The established phototoxin chlorpromazine, and also cisplatin were used as controls. During clinical PDT, the drug-light interval varies between 3 – 48 h and irradiation is usually less than 1h.

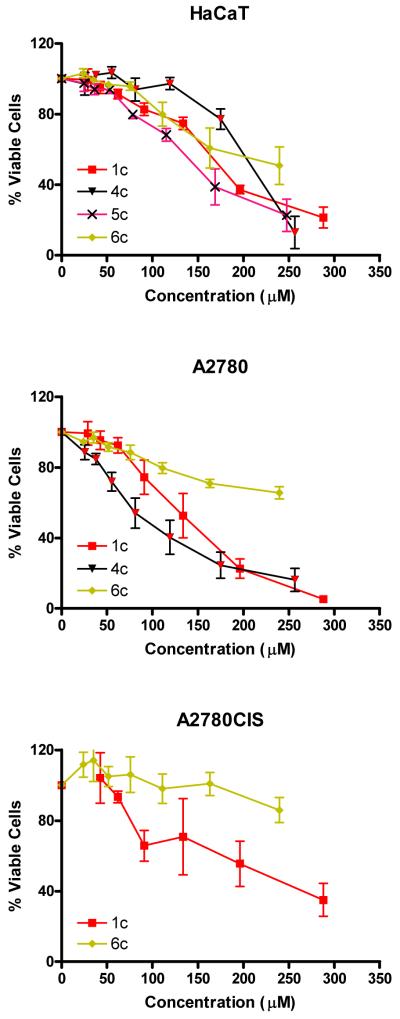

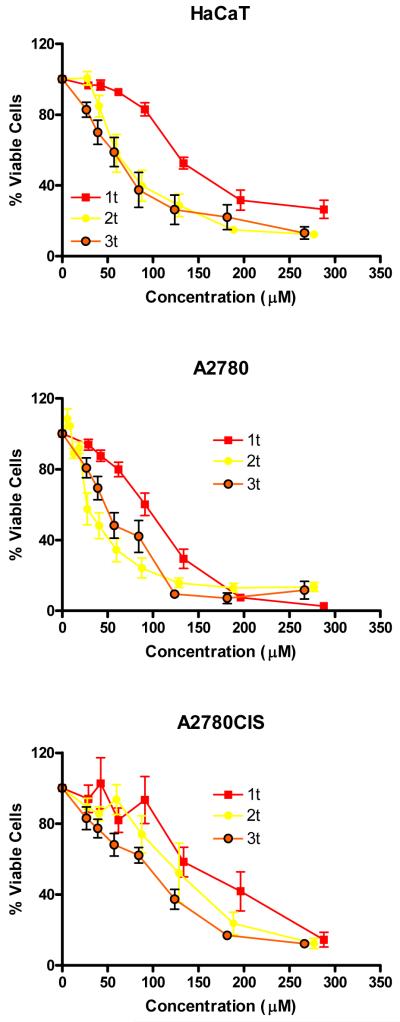

Generally, A2780 carcinoma cells were more sensitive to the effects of the complexes compared to either immortalized keratinocytes or the cisplatin-resistant derivative ovarian carcinoma cell line (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of UV (λmax 365 nm) on toxicity of diazido PtIV complexes towards human keratinocytes (HaCaT), wild-type (A2780) and cisplatin-resistant A2780 (A2780CIS) ovarian cancer cells in comparison with cisplatin (CisPt) and chlorpromazine (CPZ)

| Complex | IC50 (μM)[a] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HaCaT | A2780 | A2780CIS | ||||

| +365 nm | Dark | +365 nm | Dark | +365 nm | Dark | |

| 1c [b] | 169.3 | >287.9[c] | 135.1 | >287.9 | 204.9 | >287.9 |

| 1t [b] | 121.2 | >287.9 | 99.2 | >287.9 | 163.6 | >287.9 |

| 2t | 65.6 | >276.8 | 39.8 | >276.8 | 128.7 | >276.8 |

| 8c | 131.0 | >236.3 | 65.9 | >236.3 | 165.2 | >236.3 |

| 8t | 54.0 | >236.3 | 51.0 | >236.3 | 59.7 | >236.3 |

| 7c | 100.9 | >244.4 | 79.6 | >244.4 | 108.7 | >244.4 |

| 7t [b] | 6.8 | >244.4 | 1.9 | >244.4 | 16.9 | >244.4 |

| 9c | >236.2 | >236.2 | 63.6 | >236.2 | >236.2 | >236.2 |

| 9t | 22.0 | 144.1 | 2.6 | 26.8 | 2.9 | 57.7 |

| 3t | 68.3 | >266.5 | 58.4 | >266.5 | 90.1 | >266.5 |

| 11t | 61.0 | 108.0 | 15.8 | 31.3 | 38.2 | 54.4 |

| 10t | 7.1 | 97.8 | 4.2 | 108.7 | 5.4 | 134.9 |

| 4c | 203.9 | >256.9 | 93.4 | >256.9 | NT | NT |

| 5c | 149.9 | >247.9 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 6c | 224.3 | >239.6 | >239.6 | >239.6 | >239.6 | >239.6 |

| CisPt | 144.0 | 173.3 | 151.3 | 152.0 | 261.0 | 229.0 |

| CPZ | 9.0 | 239.7 | 5.7 | 193.9 | 4.9 | 112.0 |

IC50: concentration of complex that reduced neutral red dye uptake by 50%. Data were calculated from non-linear regression of concentration-response curves obtained from 2-4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Goodness-of-fit was determined by the 95% confidence intervals and the R2 value

No IC50 value determined within concentration range used. NT = Not tested.

In all instances, trans complexes were more photoactive than their cis isomers (Table 2). The trans pyridine complex (7t) which we previously reported (11) to have very high potency was the most phototoxic molecule tested, taking into account its cytotoxicity (“dark” toxicity: Table 2) and activity across the three cell lines. Two complexes (9t & 10t) were more or equally as phototoxic to A2780CIS cells as 7t, but both these complexes were also cytotoxic under the conditions of the assay. Figure 4 summarizes this by ranking the complexes according to the fold difference toxicity in the presence of irradiation compared to its absence.

Figure 4. Phototoxic index.

PtIV azido complexes ranked in order of decreasing phototoxic index for the three cell lines (HaCaT A2780, A2780cis). The phototoxic index is defined as the fold difference in toxicity +/− UV.

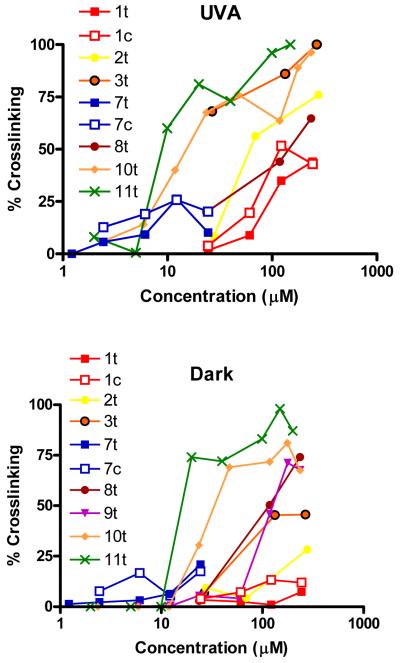

Some complexes were tested for DNA reactivity using the comet assay. The ability of the analogues to antagonize H2O2-mediated strand breaks (indicating DNA crosslinking) showed that in general, DNA reactivity detected by the comet assay was not predictive of phototoxicity (Figure 5). For example, 7c was approximately 10-fold less phototoxic to HaCaT cells than 7t, but was more effective at inhibiting DNA migration (at low doses). The sham-irradiated samples demonstrated decreased crosslinking as might be expected from the toxicity data, but some degree of inhibition of DNA migration was noted even with molecules that showed no detectable cytotoxicity under the experimental conditions (e.g. 3t). The cytotoxic complexes effectively inhibited DNA migration even in the absence of irradiation.

Figure 5. Single cell gel electrophoresis assay.

A: Individual cell nuclei are embedded in an agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis. Relaxation of DNA supercoiling as a result of strand breaks results in the DNA being pulled out of the nucleus to form a comet ‘tail’. The fluorescence intensity of the image and extent of DNA migration can be quantified by image analysis. B: Crosslinking molecules antagonise the extent of DNA migration. Top panel: HaCaT nuclei treated with Cisplatin showing no DNA migration; Middle panel: HaCaT nuclei treated with clastogen to introduce strand breaks and produce significant DNA migration; Bottom panel: combination of cisplatin and clastogen showing inhibition of DNA migration caused by the crosslinking effect of cisplatin.

Discussion

All of the complexes exhibited good aqueous solubility.

Photochemistry

UV-visible spectroscopy showed the rapid loss of the LMCT band characteristic of the PtIV complexes on irradiation of aqueous solutions of the six cis complexes 4c-9c with low-power UVA light (λ = 365 nm) indicating that the complexes were being photoreduced to PtII. The photodecomposition pathways can involve azide or ammonia release and reduction of PtIV to PtII with N2 production (20). The photochemistry of PtII azido complexes has been studied in more detail than that of PtIV azido complexes (28), and from this we reflect that possible mechanisms of photochemical reactivity could include photosubstitution, photodissociation, photoisomerisation as well as the observed photoreduction. It is also possible that the photosensitised production of singlet oxygen could be involved, and work is underway to determine if this is the case. In general, we believe that the exact pathway is highly dependent on the solution conditions. The cytotoxic mechanism could therefore involve PtII species analogous to cisplatin (more reactive than their PtIV prodrugs) but also the other released low-molecular-weight species.

Dark toxicity

Whilst all of the cis complexes tested were stable in the dark, the all-trans derivatives containing 3-methyl- (10t) or 4-methylpyridine (9t) ligands showed moderate dark toxicity whereas the 2-methylpyridine all-trans isomer (8t) did not. One possible explanation for dark toxicity might be the chemical reduction of PtIV to PtII in the absence of irradiation, a process which is induced by biological reductants such as glutathione (GSH) (29). The mechanism of biological reduction is not well-understood. The activity of this series of isomers (and compared to the pyridine derivative 7t) suggests steric and/or electronic effects could be responsible. The 2-methyl group is likely to afford greater steric protection from attack at the PtIV center. However, inclusion of a bromine atom in the ortho 2-position of 3-methylpyridine (11t) results in greater, not lesser toxicity as compared to the 3-methylpyridine complex 9t, and so steric effects alone are not sufficient to stabilise the complex from attack. Electron transfer to PtIV from a reducing agent can occur through the ligands (29). Studies of the related complex trans,trans,trans-[Pt(OH)2(N3)2(NH3)(2-bromopyridine)] (data not shown) show that this complex is readily reduced by GSH which supports this hypothesis. One of the aims of this research is to design complexes which can be photoactivated by longer wavelength light; however, in general it appears that complexes with strong absorption bands at such wavelengths are more susceptible to chemical reduction.

Phototoxicity

Amine chain length

Of the complexes containing cis aliphatic amines, the butylamine containing complex 5c was the most phototoxic, when compared to complexes with both longer and shorter alkyl chains. This includes the previously reported ammine complex cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)2] 1c, which has IC50 values of 167 μM and 137 μM with UVA and blue light, respectively (see Table 2). Similarly, in the all-trans derivatives replacement of NH3 by alkylamines increased the phototoxicity: the all-trans methylamine (2t) and ethylamine (3t) complexes which were more phototoxic than the previously reported bis ammine complex 1t, trans,trans,trans-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)2] the latter of which shows IC50 values of 121.2 and 104.9 μM in HaCaT cells with UVA and blue light respectively.

Aromatic versus aliphatic amine ligands

For both cis and trans isomers there is a significant improvement in phototoxicity following inclusion of pyridyl derivatives as ligands. The most photoactive compounds were those containing pyridine itself or a methylated pyridine. These complexes were significantly more potent than cisplatin tested under identical experimental conditions (Table 2). Despite having minimal absorption at wavelengths above 400 nm, preliminary experiments show that some of the complexes were photoactivated with blue visible light (Table 3: TL03: λmax = 420 nm, filtered to cut-off wavelengths below 400 nm). Photoactivity is reproducible, but this is an observation that requires further investigation. Theory predicts the presence of very weak absorption bands in the visible region of some diazido complexes (20c). Predicting photoreactivity from absorption spectra can be difficult and in many cases can only identify a likely waveband. Spectra are generally determined in optically clear solvents, of the parent compound, and not in the biological milieu. The yield of excited state molecule, which we have not measured and which is influenced by the physical environment of the chromophore, is a critical factor in determining whether a molecule is likely to have phototoxic potential. There is precedent for the photoreactivity of a photoactive metal complex to be significantly different from what might be predicted from its absorption spectrum, postulated to result from the direct population of low lying triplet states upon irradiation with visible light (30).

Table 3.

Effect of visible light (λmax 420 nm) on toxicity of diazido PtIV complexes towards HaCaT cells

| Complex | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| 7t | 85.9 |

| 2t | 163.3 |

| 3t | 98.3 |

| 8t | 89.9 |

| 10t | 11.9 |

| 9t | 14.6 |

| 7c | 116.5 |

Inclusion of an aromatic ligand appears to provide a significant increase in photocytotoxicity, but can also introduce instability in the dark. Since 7t represents the most phototoxic complex which still maintains dark stability, introducing longer alkyl chains (methyl-, ethyl-, propylamine) in place of the NH3 group may increase phototoxicity whilst maintaining dark stability, since the trans methyl and ethylamine aliphatic complexes, 2t and 3t were more phototoxic than the NH3 derivative (1t). It seems likely that longer chain amines do not dissociate following irradiation as readily as NH3 does; by analogy, loss of NH3 from cisplatin adducts on DNA is known to be detrimental to its cytotoxic effect (31).

Isomers with aromatic amines

Different pyridyl ring substitutions also had significant effects on the phototoxicity. Of the cis pyridyl complexes, the 3-methylpyridine complex 9c was the least phototoxic, and since it did not show significant phototoxicity in HaCaT cells it was not tested further. The only difference in the structures of 8c and 9c is the position of the methyl group on the pyridine ring. In contrast to 9c, the pyridine complex 7c and 2-methylpyridine complex 8c were both phototoxic, showing comparable phototoxicity across the three different cell lines. In the analogous PtIV chlorido complexes cis,trans,cis-[PtCl2(OH)2(NH3)(R)], for R = 2-methylpyridine the complex is reduced (without irradiation) more easily than the R = pyridine analogue; a feature attributed to the destabilising influence of the steric bulk of the 2-methylpyridine (32). Since 8c was not cytotoxic in the absence of irradiation it is concluded that this steric bulk is not sufficiently destablising to cause spontaneous reduction of 8c (or 8t) in the dark.

The products of photoreduction of these octahedral PtIV complexes are likely to be square-planar PtII complexes, and so it is relevant to consider the reactivity of the potential PtII reduction products. For the complexes with pyridyl derivatives as ligands, the PtII-2-methylpyridine complex is the most highly sterically hindered, with the methyl group lying directly over the platinum square plane. This steric bulk of the 2-methylpyridine ligand may also allow for stereoselective interactions with target biomolecules (33) and limit deactivation (34). The lack of steric bulk about the platinum centre of 9c may promote deactivation within the cells, accounting for the low toxicity of this complex.

Cis-trans isomerism

8c and 7c were the most phototoxic cis compounds investigated. The fact that cis analogues were less potent than their trans isomers in all cases is of interest given the clinical ineffectiveness of transplatin compared to cisplatin. Transplatin is also much less effective in cell culture models. Since transplatin is now known to be a “special case” (15-18), recent data on trans diamine PtII complexes and the present data on photoactivated PtIV complexes suggest that trans platinum complexes have potential as future anticancer agents. We also note that despite the lower activity of the cis complexes, the irradiated complexes are still more toxic towards HaCaT, A2780 and cisplatin-resistant A2780 (A2780cis) cells than cisplatin tested under the same experimental conditions (Table 2), and show no toxicity in the absence of irradation.

The phototoxicity of the PtIV complexes does not readily correlate with that of the corresponding PtII chlorido derivatives, which suggests that these PtIV azido complexes are not simply acting as prodrugs of their PtII precursors. It is likely that the phototoxicity is dependent on a number of factors of which the toxicity of the released PtII species is just one. Furthermore, there is no simple correlation between absorbance (extinction coefficient) at the wavelength of irradiation (e.g. 365nm) and photocytotoxicity. Further work needs to be done to investigate the structure-activity relationships for complexes of this type.

Comet Assay

The comet assay is a relatively rapid method of screening for DNA reactivity. In this study, we used a sub-toxic dose of H2O2 to produce DNA strand breaks following the photoactivation of the Pt complex. The strand-nicking activity of the peroxide will relax and break the DNA within the nucleus, allowing it to move through a gel during electrophoresis. Crosslinking will antagonise the DNA migration (35). In our hands this approach is very reproducible compared to other ways of achieving this effect, and works well with other photoactivated crosslinkers such as psoralens. For the PtIV complexes tested, the comet assay showed that DNA crosslinking increased upon irradiation, suggesting that DNA is a target for these compounds. The nature of these DNA lesions remains to be determined (the assay cannot distinguish between different types of lesions unless specific DNA recognition/repair enzymes are included), as some of the complexes showed similar ability to inhibit DNA migration but had very different phototoxicities. This opens up the possibility that distinct DNA adducts are involved and/or processing by the DNA damage and repair machinery. Other cellular targets may also be involved in the lethal response.

In the dark, some complexes induced significant DNA crosslinking despite being non-cytotoxic under the experimental conditions used. This is similar to what is observed with tranplatin, which can effectively inhibit DNA migration in the comet assay but has minimal ability to kill cells.

Variability of toxicity across different cell lines

Some complexes (e.g. 8t) were similarly toxic to all three cell lines, while others (e.g. 9c) demonstrated cell-type specific differences. The cause of this remains unexplored and could reflect differences in uptake and retention of the complexes; or differences in the cytotoxic protective mechanisms of the cells (detoxification systems and DNA repair capacity). Morphologically, the cell lines are visually distinct from one another, with the A2780 cells presenting the smallest surface area. Understanding how the individual complexes are handled by the cell will help direct the design of future phototoxic molecules.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Phototoxicity of Pt complexes.

In HaCaT, A2780 cells and A2780CIS cells. Cells were irradiated with 5 J cm−2 filtered UVA as described in the methods section. Data are the mean ± SE of 4/6 monolayers from 2/3 independent experiments. The viability of cells irradiated with 5 J cm−2 UVA compared to those kept in the dark was > 90% in all experiments. Figure subdivided by complexes a) 7c, 8c, 9c; b) 7t, 8t, 9t, 10t, 11t; c) 1c 4c 5c 6c; d) 1t, 2t, 3t.

Figure 2. Cytotoxicity of Pt complexes.

Panel A: HaCaT cells; Panel B: A2780 cells; Panel C: A2780CIS cells. Cells were treated identically as for Figure 1, but were given a sham irradiation. These experiments were conducted in parallel with the phototoxicity experiments (ie. each complex was tested in a “light” & “dark” plate). Data are the mean ± SE of 4/6 monolayers from 2/3 independent experiments. Figure subdivided by complexes a) 7c, 8c, 9c; b) 7t, 8t, 9t, 10t, 11t; c) 1c 4c 5c 6c; d) 1t, 2t, 3t.

Figure 3. Induction of DNA crosslinking by photoactivated Pt complexes.

DNA migration was induced by incubating irradiated cells with H2O2 before cells were processed in the comet assay. Migration of coded samples was assessed by image analysis (Komet v. 5.5) and the degree of crosslinking calculated. A: Irradiated samples; B: Sham irradiated samples (5 J cm−2 UVA). Data points represent the mean of 4/6 monolayers from 2/3 independent experiments. Background DNA migration: +UVA: 9.9 ± 1.5%; Sham: 8.8 ± 1.1%.

Table 4.

Fold difference in toxicity of photoactivated Pt complexes compared to cisplatin tested under identical conditions (i.e. values > 1 indicate greater potency for photoactivated complexes)

Acknowledgement

We thank Scottish Enterprise (Proof-of-Concept Award), the EPSRC (EP/G006792/1) and the MRC (G070162) for support, and members of EC COST Action D39 for stimulating discussions. We thank Science City/AWM/ERDF for funding the MAXIS mass spectrometer. We thank Ana Pizarro for HPLC and Simon Parsons for acquiring and solving the X-ray crystallographic structure of 4c given in the SI.

Table of Contents Graphic

Footnotes

Supporting information available. X-ray crystallographic data (deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as CCDC 750126) collection details, figures showing thermal ellipsoids and crystal packing of 4c. Irradiation studies of complexes 4c-9c as followed by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy.

References

- (1).Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sharman WM, Allen CM, van Lier JE. Photodynamic therapeutics: basic principles and clinical applications. DDT. 1999;4:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McCoy CP, Rooney C, Edwards CR, Jones DS, Gorman SP. Light-Triggered Molecule-Scale Drug Dosing Devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9572–9573. doi: 10.1021/ja073053q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jiang MY, Dolphin D. Site-Specific Prodrug Release Using Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4236–4237. doi: 10.1021/ja800140g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Farrer NJ, Sadler PJ. Photochemotherapy: Targeted Activation of Metal Anticancer Complexes. Aust. J. Chem. 2008;61:669–674. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Brown SB, Brown EA, Walker I. The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ibbotson SH, Moseley H, Brancaleon L, Padgett M, O’Dwyer M, Woods JA, Lesar A, Goodman C, Ferguson J. Photodynamic therapy in dermatology: Dundee clinical and research experience. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2004;1:211–223. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).a) Stewart F, Baas P, Star W. What does photodynamic therapy have to offer radiation oncologists (or their cancer patients)? Radiother. Oncol. 1998;48:233–248. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nyst HJ, Tan IB, Stewart FA, Balm AJM. Is PDT a good alternative to surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck cancer? Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2009;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Harris AL. Hypoxia - a key regulatory factor in tumor growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bednarski PJ, Mackay FS, Sadler PJ. Photoactivatable platinum complexes. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2007;7:75–93. doi: 10.2174/187152007779314053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Mackay FS, Woods JA, Heringova P, Kasparkova J, Pizarro AM, Moggach SA, Parsons S, Brabec V, Sadler PJ. A potent cytotoxic photoactivated platinum complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:20743–20748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707742105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hall MD, Mellor HR, Callaghan R, Hambley TW. Basis for design and development of platinum (IV) anticancer complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3403–3411. doi: 10.1021/jm070280u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mackay FS, Farrer NJ, Salassa L, Tai H-C, Deeth RJ, Moggach SA, Wood PA, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. Synthesis, characterization and photochemistry of PtIV pyridyl azido acetato complexes. Dalton Trans. 2009;13:2315–2325. doi: 10.1039/b820550g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).a) Goddard PM, Orr RM, Valenti MR, Barnard CFJ, Murrer BA, Kelland LR, Harrap KR. Novel trans platinum complexes: Comparative in vitro and in vivo activity against platinum-sensitive and resistant murine tumors. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Coluccia M, Boccarelli A, Mariggio MA, Cardellicchio N, Caputo P, Intini FP, Natile G. Platinum(II) complexes containing iminoethers: a trans platinum antitumour agent. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1995;98:251–266. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(95)03650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Coluccia M, Nassi A, Boccarelli A, Giordano D, Cardellicchio N, Locker D, Leng M, Sivo M, Intini FP, Natile G. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity and cellular pharmacological properties of new platinum-iminoether complexes with different configuration at the iminoether ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;77:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kelland LR, Sharp SY, O’Neill CF, Raynaud FI, Beale PJ, Judson IR. Discovery and development of platinum complexes designed to circumvent cisplatin resistance. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;77:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Aris SM, Farrell NP. Towards antitumor active trans-platinum compounds. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009:1293–1302. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200801118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Natile G, Coluccia M. Current status of trans-platinum compounds in cancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001;216–217:383–410. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ramos-Lima FJ, Vrána O, Quiroga AG, Navarro-Ranninger C, Halámiková A, Rybnícková H, Hejmalová, Brabec V. Structural characterization, DNA interactions, and cytotoxicity of new transplatin analogues containing one aliphatic and one planar heterocyclic amine ligand. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:2640–2651. doi: 10.1021/jm0602514. and L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Najajreh Y, Kasparkova J, Marini V, Gibson D, Brabec V. Structural characterization and DNA interactions of new cytotoxic transplatin analogues containing one planar and one nonplanar heterocyclic amine ligand. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005;10:722–731. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mackay FS, Woods JA, Moseley H, Ferguson J, Dawson A, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. A photoactivated trans-diammine platinum complex as cytotoxic as cisplatin. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:3155–3161. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).a) Ronconi L, Sadler PJ. Unprecedented carbon-carbon bond formation induced by photoactivation of a platinum(IV)-diazido complex. Chem. Commun. 2008;2:235–237. doi: 10.1039/b714216a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Phillips HIA, Ronconi L, Sadler PJ. Photoinduced reactions of cis,trans,cis-[PtIV(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)2] with 1-methylimidazole. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:1588–1596. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Salassa L, Phillips HIA, Sadler PJ. Decomposition pathways for the photoactivated anticancer complex cis,trans,cis-[Pt(N3)2(OH)2(NH3)2]: insights from DFT calculations. PCCP. 2009 doi: 10.1039/b912496a. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mackay FS, Moggach SA, Collins A, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. Photoactive trans ammine/amine diazido platinum(IV) complexes. Inorg. Chim. Act. 2009;362:811–819. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Farrell N. Transition Metal Complexes as Drugs and Chemotherapeutic Agents. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 1989. pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cubo L, Quiroga AG, Zhang J, Thomas DS, Carnero A, Navarro-Ranninger C, Berners-Price SJ. Influence of amine ligands on the aquation and cytotoxicity of trans-diamine platinum(II) anticancer complexes. Dalton Trans. 2009;18:3457–3466. doi: 10.1039/b819301k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Abrams MJ, Giandomenico CM, Vollano JF, Schwartz DA. A convenient preparation of the amminetrichloroplatinate(II) anion. Inorg. Chim. Act. 1987;131:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Barton SJ, Barnham KJ, Habtemariam A, Sue RE, Sadler PJ. pKa values of aqua ligands of platinum(II) anticancer complexes: [1H, 15N] and 195Pt NMR studies of cis- and trans-[PtCl2(NH3)(cyclohexylamine)] Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1998;273:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Woods JA, Young AJ, Gilmore IT, Morris A, Bilton RF. Menadione induced DNA damage as measured by the comet assay. Free Radical Res. 1997;26:113–124. doi: 10.3109/10715769709097790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Spielmann H, Lovell WW, Hclzle E, Johnson BE, Maurer T, Miranda MA, Pape WJW, Sapora O, Sladowski D. In vitro phototoxicity testing: The report and recommendations of ECVAM workshop 2. ATLA Altern. Lab. Anim. 1994;22:314. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hennig H, Stich R, Knoll H, Rehorek D, Stufkens DJ. Photochemistry and photocatalytic reactions of mixed-ligand azido transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1991;111:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lemma K, Shi T, Elding LI. Kinetics and mechanism for reduction of the anticancer prodrug trans,trans,trans-[PtCl2(OH)2(c-C6H11NH2)(NH3)] (JM335) by thiols. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:1728–1734. doi: 10.1021/ic991351l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Loganathan D, Morrison H. Effect of Ring Methylation on the Photophysical, Photochemical and Photobiological Properties of cis-dichlorobis(1,10-Phenanthroline) - Rhodium(III)Chloride. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006;82:237–247. doi: 10.1562/2005-01-19-RA-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lau JK-C, Deubel DV. Quantum chemical studies of metals in medicine. IV. Loss of ammine from platinum(II) complexes: Implications for cisplatin inactivation, storage, and resistance. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:2849–2855. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Battle AR, Choi R, Hibbs DE, Hambley TW. Platinum(IV) Analogues of AMD473 (cis-[PtCl2(NH3)(2-picoline)]): Preparative, Structural, and Electrochemical Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:6317–6322. doi: 10.1021/ic060273g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Chen Y, Parkinson JA, Guo Z, Brown T, Sadler PJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:2060–2063. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990712)38:13/14<2060::AID-ANIE2060>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kelland LR. In: Cisplatin: chemistry and biochemistry of a leading anticancer drug. Lippert B, editor. Wiley-VCH; Zurich: 1999. pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Pfuhler S, Wolf HU. Detection of DNA-crosslinking agents with the alkaline comet assay. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1996;27:196–201. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1996)27:3<196::AID-EM4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.