Abstract

In-vivo electrophysiological recordings from cell bodies of primary sensory neurons are used to determine sensory function but are commonly performed blindly and without access to voltage-(patch-clamp) electrophysiology or optical imaging. We present a procedure to visualize and patch-clamp the neuronal cell body in the dorsal root ganglion, in vivo, manipulate its chemical environment, determine its receptive field properties, and remove it either to obtain subsequent molecular analyses or to gain access to deeper lying cells. This method allows the association of the peripheral transduction capacities of a sensory neuron with the biophysical and chemical characteristics of its cell body.

Keywords: In vivo visualization, Primary sensory neuron, Dorsal root ganglion, Patch-clamp electrophysiology, Calcium imaging

1. Introduction

Peripheral somatic sensory neurons are functionally heterogeneous, encompassing both nociceptive and non-nociceptive types which transduce a variety of stimuli from touch to temperature. An understanding of the mechanistic basis of sensory transduction requires the correlation of ion channel expression and other molecular processes with sensory modality. However, current methodologies have limited ability to achieve this aim. Dissociation of peripheral sensory neurons allows patch clamp recording for measurement of receptor- and ion-channel activity as well as optical imaging, and the harvesting of single neurons for gene expression analysis. But dissociation eliminates the peripheral field resulting in an inability to test sensory modality or the response of the peripheral field to chemical agents. The neuronal cell body (soma) is unlikely to have exactly the same molecular properties as those of the terminal endings (Zimmermann et al., 2009). In addition, dissociation, by itself, alters the excitability, intracellular signaling and gene expression of neuronal somata (Ma and LaMotte, 2005; Zheng et al., 2007; Zimmermann et al., 2009). Alternatively, sharp electrode recordings from intact ganglia retain peripheral properties (Koerber et al., 1988; Lawson et al., 1997) but offer limited ability for voltage control or manipulation/ harvesting of an identified neuron since it is not visualized and its membrane is tightly bound to other cells. The cells are also not accessible for optical imaging or patch-clamp recording of ion channels and isolated currents.

We provide a procedure to apply the advantages of the in-vitro methods in vivo. Using a physiological preparation designed for adult mice and rats, we describe how to a) visualize the neuronal soma in vivo, b) control/manipulate its external chemical environment, c) determine its receptive field properties without damage, d) image its ionic activities and those of its non-neuronal neighboring cells, e) make it accessible to patch-clamp electrophysiological recording, and/or f) remove it for the purpose of subsequent molecular analyses and to gain access to deeper lying cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 180-250 g (n = 34) and male CD1 mice weighting 35-40 g (n = 28) or C57BL/6 mice weighing 25-30 g (n = 2) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Groups of three or four animals were housed together in a climate-controlled room under a 12 hour light/dark cycle. The use and handling of animals were in accordance with guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain and received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine.

2.2 In-vivo physiological preparation

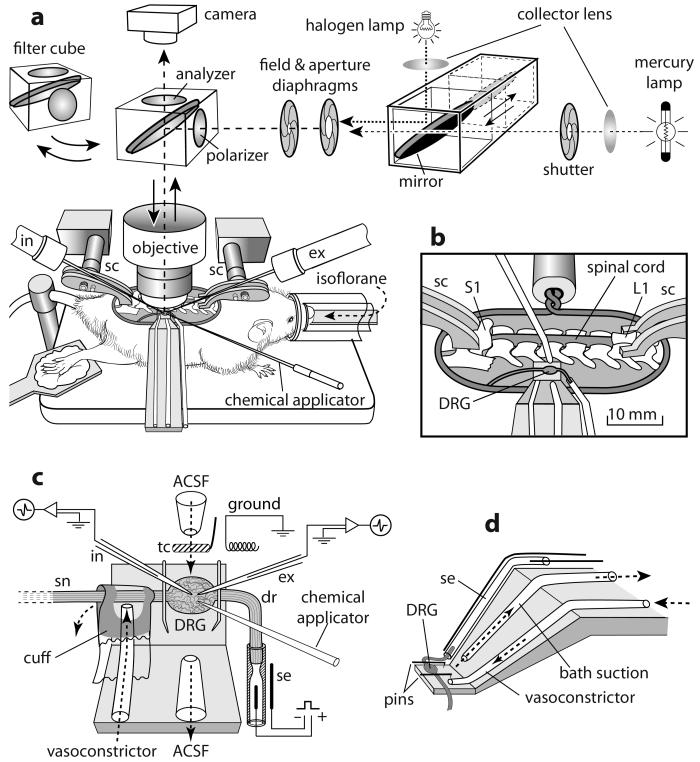

A surgical procedure for the rat (Ma and LaMotte, 2007) was adapted to the mouse by reducing the size of the ring, vertebral clamps and platform for the DRG (Fig. 1a). Rats and mice were anesthetized, respectively, with pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal, 50 mg/kg i.p. initial dose and 20 mg/kg i.p. supplemental dose) and isoflurane inhalation (1-2% via a nose cone). After a laminectomy at the levels of L2-L6, the L3 or L4 DRG with the corresponding spinal nerve and dorsal root were exposed and isolated from the surrounding tissue. Oxygenated ACSF (Ma et al., 2003) was dripped periodically on to the surface of the ganglia to prevent drying and hypoxia. Two lumbar vertebrae (L1 and S1) were clamped to posts attached to a “base plate” that held the animal (Fig. 1a, b). The skin was sewn to a ring (fixed to a post on the base plate) to hold a pool of warm, oxygenated, artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). The ACSF contained (in mM): 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, and 10 Dextrose. The solution was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and had a pH of 7.4 and an osmolarity of 290~310 Osm. A vasoconstricting drug, [Arg8]-Vasopressin (10 μM in oxygenated ACSF, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was applied via a syringe attached to a soft cuff wrapped around the spinal nerve just distal to the DRG and sealed at each end with Vaseline (Fig. 1c). The vasoconstrictor stopped or substantially reduced the blood flow to the capillary bed in the DRG - thereby preventing the bleeding that otherwise would occur after the subsequent application of collagenase. A successful blockade of blood flow was achieved in 91% (31/34) of rats and 97% (29/30) of mice. The epineurium covering the DRG was removed under a dissection microscope. Then, the base plate with the animal was transferred and mounted to a frame under the objective of an upright, light microscope (BX51WI, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) on a pneumatic vibration isolation table. The dorsal root was cut and the DRG lifted onto a small platform that was fixed to the base plate. The DRG was continuously superfused at a rate of 3 ml/min by the oxygenated ACSF that was preheated by an in-line heater (TC-344A, Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT, USA) to achieve a desired temperature of 37 °C (via feedback from a thermocouple near the ganglion) (Fig. 1b,d). Suction was used to maintain the level of fluid in the pool. The proximal end of the dorsal root was brought into a suction electrode to electrically stimulate the axon of a recorded neuron and determine its axonal conduction velocity (Fig. 1c). The DRG was viewed through a 40X water immersion objective (magnification of 400X) using reflective microscopy via an analyzer-50/50 mirror-polarizer set (as shown in Fig. 1a) (Ma and LaMotte, 2007). A light source for recording of epifluorescence was delivered from above in a conventional way via appropriate filter sets. A pipette to deliver chemicals (via an 8-channel pressurized chemical delivery system, ALA Scientific Instruments, Long Island, NY, USA) and pipette electrodes were brought in from left and right sides, and under the objective, at angles of approximately 30-35 degrees (Fig. 1a,c).

Figure 1.

Physiological preparation shown for the mouse. (a) After laminectomy, the skin was sutured to a ring and the animal rested on a plate attached to which were two spinal vertebrate clamps (sc) on the rostral (L1) and caudal (S1) region. As shown in the enlarged view (b), the L3 (or L4) DRG on the right side was exposed, pinned to a small platform beneath, and superfused with oxygenated ACSF. The surface of the DRG was viewed through a 40x water immersion objective using either reflection microscopy in bright field via an analyzer-50/50 mirror-polarizer set and halogen lamp (a) or epifluorescence (after switching to a filter cube and mercury lamp). As further enlarged in (c), a cuff around the spinal nerve (sn) delivered a vasoconstrictor via a tube to block the blood flow in the DRG. The DRG was held by two insect pins inserted into a thin layer of silicon rubber attached to the platform. The dorsal root (dr) was transected and its distal end attached to a suction electrode (se). Intracellular (in) and extracellular (ex) electrophysiological recording electrodes and a topical chemical applicator are shown. The vasoconstrictor was applied via a cuff around the nerve to block the blood flow. tc: thermocouple. (d) Oblique view of the platform and perfusion tubing. A similar but larger recording scaffold was used for recordings from rats.

2.3 Application of vasoconstrictor and collagenase

Prior to application of the vasoconstrictor, the capillary blood flow could be viewed clearly on the surface of the ganglion (see Supplementary Video). Once blood flow was significantly slowed or stopped, collagenase P (1 mg/ml, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was applied to a local region of the DRG via a pipette located close to the surface. The bath perfusion was temporarily turned off for about 5 minutes during the application. Repetitive collagenase application was performed until the neuronal somata were loosened up from the surrounding connective tissue (1-2 applications, for extracellular recording or calcium imaging) and the SGCs (2-3 applications, for patch-clamp recordings). Sharp-electrode intracellular recording could be performed without collagenase digestion (Ma and LaMotte, 2007). Successful blockade of blood flow was essential if topical collagenase were to be applied (as needed for patch-clamp and extracellular electrophysiological recording). Otherwise the collagenase-induced bleeding from the capillary network would cover the surface of DRG and block the view of the neuronal somata.

2.4 Electrophysiological recording

The extracellular recording electrode was a pipette whose tip (fire polished with Microforge MF-830, Narishige, Japan) diameter was chosen to be about the same size as the cell to be recorded. Because the neuronal soma was loosened from its neighbors but tethered by a loose axon, it could be drawn into the mouth of the pipette with gentle suction, thereby allowing action potentials to be recorded (via an extracellular amplifier) under exceptionally stable conditions without injury to the cell (Fig. 2 and 3). The conduction velocity (CV) was obtained by dividing the latency of a somal AP, extracellularly evoked by stimulating the cut end of the dorsal root with a suction electrode, by the distance between the electrode and the soma (Ma and LaMotte, 2007; Ma et al., 2003). This distance was adequate for obtaining the CVs of unmyelinated axons. For the faster conducting myelinated axons, the distance was sometimes too short in which case the CV was obtained via electrical stimulation of the peripheral receptive field. Once the CV and peripheral receptive field properties of a recorded cell were determined, the suction was released and the soma was moved out of the extracellular pipette. The soma was then available for intracellular sharp-electrode recording (Fig. 2) (Ma and LaMotte, 2005, 2007; Ma et al., 2003). Alternatively, or, in addition, whole cell patch-clamp recordings could be performed (Fig. 4) as described for the intact DRG, in vitro 998)(Hayar et al., 2008), or for dissociated neurons in acute culture (Tan et al., 2006). In the present study, the sharp electrode for intracellular recording was filled with 2M potassium acetate (KAC) and had a resistance of 60-80 MΩ. For whole cell patch-clamp recording of sodium currents, the patch pipette (resistance 1.5-2 MΩ) was filled with an internal solution containing: 110 CsF, 10 NaCl, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, the PH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH, and the osmolarity adjusted with sucrose to about 300 mOsm,. The extracellular solution contained: 35 NaCl, 115 TEA-Cl, 10 4-AP, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 2 BaCl2, 1 CaCl2, 0.1 CdCl2, pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl and osmolarity adjusted to about 300 mOsm. For tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-R) current recording, TTX (1uM) was included in the external solution.

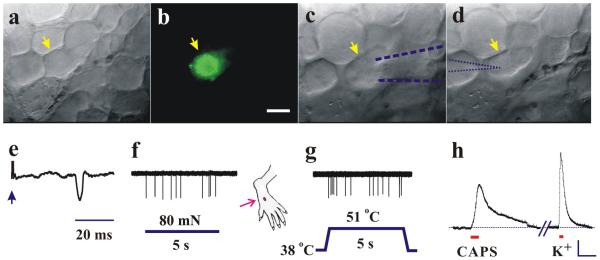

Figure 2.

In-vivo visualization and recordings of action-potential activity in polymodal nociceptive DRG neurons in mouse. Neuronal somata on the surface of DRG viewed under bright-field reflection microscopy (a, c and d) and epifluorescence (b). A neuronal soma, yellow arrow in (a), was identified as nociceptive and supplying a cutaneous site on dorsum of hindpaw by the presence of the fluorescent dye, Alexa-fluor- 488-conjugated IB4 (b) retrogradely transported from prior injection into the site. (c) After topical collagenase, a micropipette (blue dashed outline), applying gentle suction to the soma, extracellularly recorded action potentials evoked by electrical pulses (arrow in e) from the dorsal root (indicating C-fiber conduction velocity) or by stimulation of the peripheral receptive field (red arrow) by a von Frey filament (f) or heat from a Peltier thermode (g) classifying the neuron as a “C-polymodal nociceptor” (CPN). (d) After electrode withdrawal, an intracellular electrode (blue dotted outline) impaled the same soma and recorded a membrane-potential depolarization (h) to capsaicin (CAPS, 1 μM), and to high potassium (K+, 30 mM) each topically applied to the soma. Scale bars: 20 μm (b); 10 mV, 20s (h).

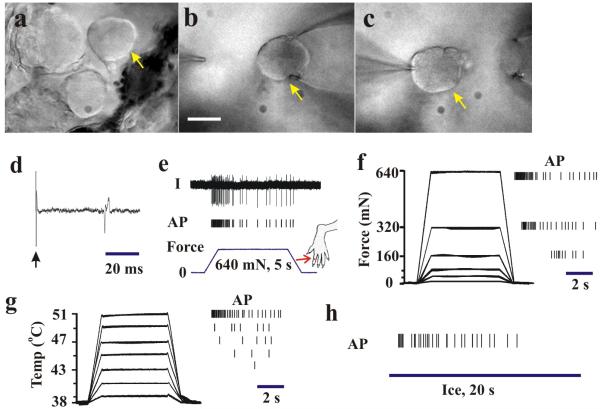

Figure 3.

In-vivo electrophysiological recording from a small-diameter, C-polymodal DRG neuron in the rat. After collagenase treatment, a neuronal soma (arrow in a-c) was accessed first by a micropipette using gentle suction (b, scale bars: 20 μm) for extracellular recording (d-h) and then by a patch electrode (c) to obtain whole-cell patch clamp recording (see Fig. 4). (d) Action potential (AP) evoked by electrical stimulus (arrow) of dorsal root revealed an axonal conduction velocity of 0.61 m/s. (e) Original recording trace (top) and vertical tic marks beneath, each indicating the occurrence of an AP in response to punctuate mechanical indentation of 640 mN with a 200 μm diameter probe controlled by a servomotor (force trace on bottom). The receptive field is marked by an arrow on the toe. (f) Responses to graded forces of indentation with the motor-controlled 200 μm diameter probe. Evoked APs to each force indicated by tic marks on right. (g) Responses to graded heat stimuli delivered with a Peltier thermode. Temperature traces indicate stimuli of 39 to 51 °C (left) and evoked APs (right). (h) APs evoked by a chip of ice (4 °C, 20 s). After classification of the peripheral receptive modality, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed as described in Fig. 4.

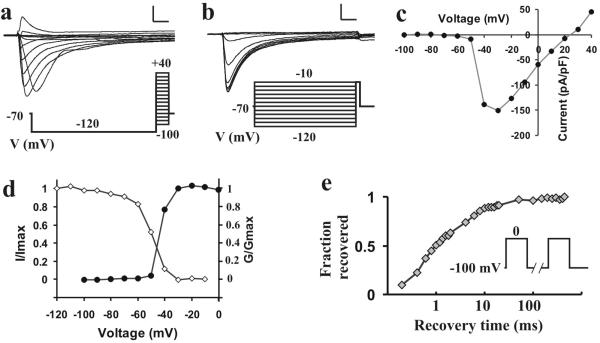

Figure 4.

In-vivo, whole cell patch-clamp recording from a functionally classified DRG neuron in the rat. The small-diameter neuronal soma functionally classified as a C- polymodal by extracellular recording (in Fig. 3) was accessed by a patch electrode (Fig. 3c) to obtain whole-cell patch clamp recording. The voltage-dependence of activation (a) and steady-state inactivation (b) of TTX-resistant sodium currents evoked by voltage commands (below) were obtained in the presence of 1 μM TTX in the extracellular solution (scale bars, 2 na, 2 ms). (c) Peak current of activation. (d) Activation (closed dots, G/Gmax) and steady-state inactivation (open dots, I/Imax) characteristics of the sodium current. (e) Recovery from inactivation of TTX-R current (voltage commands in inset). The neuron was held at −100 mV, depolarized to 0 mV for 20 ms to inactivate channels; then the same pulse was repeated after an interval of 0.2 to 500 ms. The relationship between the fraction of currents recovered and the time interval (in log scale) is plotted.

2.5 Receptive field characterization

The sensory submodality of the distal terminal was determined by the properties of the peripheral receptive field (RF) of the neuron. These properties included the type of tissue innervated (skin vs. deeper tissue such as muscle) and the type of receptive-field stimulus (e.g. mechanical, heat, cold, chemical) that elicited APs (Fig. 2 and 3). Manual exploration of the hind limb and the application of various hand held stimuli were employed for this purpose. Von Frey filaments, each with a fixed tip diameter of either 100 or 200 μM were used to deliver different bending forces. Thermal search stimuli were delivered by a chip of ice and by a temperature controlled chip-resister heating probe (Ma and LaMotte, 2007; Ma et al., 2003). Graded stimuli with servo control over force or temperature were also delivered, respectively by a motor (Zheng et al., 2002) and a Peltier thermode (Baumann et al., 1991).

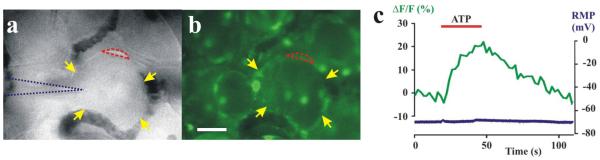

2.6 Calcium imaging

Fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (7 μM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in oxygenated ACSF was applied to the DRG in the recording chamber for 45 min. Excess dye was washed out for 15 min. The dye was preferentially taken up by the satellite glial cells (SGCs) but not by neurons. The SGCs were distinguished from neurons by their smaller size and location at the edge of the neuron (those on top are too thin to be visually distinguished). The calcium signal was acquired using a proper filter set (excitation/emission: 494nm/516nm, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and a cooled CCD camera (SensiCam, PCO, Kelheim, Germany), collected and processed using Image Workbench 5.2 (INDEC BioSystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The relative change in intracellular calcium was indicated by ΔF/F0 where F0 is the baseline fluorescence after background subtraction, and ΔF the change from baseline. Images were captured every 2s with an exposure time of 50ms using a computer-controlled shutter (Uniblitz, Rochester, NY). Chemicals (such as ATP 100μM, 30s in Fig. 5c) were applied topically to the cells under study via a pressurized drug application system (Fig. 1c). At the start of the experiment, a suitable neuronal soma with one or more labeled SGCs was selected and penetrated with a sharp electrode so that intracellular electrophysiological recordings could be performed simultaneously with calcium imaging of SGCs (Fig. 5). If desired (not shown here), a fluorescent dye emitting at a different wavelength could be applied for calcium imaging in a neuron recorded with an intracellular recording electrode via iontophoresis. This would allow simultaneous calcium imaging in both the neuron and its associated satellite glia.

Figure 5.

In-vivo neuronal recording and calcium imaging of satellite glia in rat DRG. A neuronal soma (yellow arrows in a) was impaled with a sharp electrode (dotted blue outline) after certain satellite glial cells (SCGs) were labeled with Fluo-4 - a calcium sensitive dye (b). One of the neuron’s SCGs is encircled with red for calcium imaging. (c) Topically applied ATP evoked an increase in calcium fluorescence (ΔF/F, green trace) in one of the SGCs (encircled with red in a and b) but no change in the neuronal resting membrane potential (RMP, mV, blue trace on the bottom). Scale bar: 20 μm.

3. Results

3.1 In vivo visualization of capillary blood flow and calcium fluxes

Under anesthesia, and after laminectomy and suturing the skin to a ring, the L3 or L4 DRG was exposed, its epineurium removed, placed onto a platform, and continuously perfused with an oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (Fig. 1). The dorsal root was cut and drawn into a suction electrode. Reflection microscopy with a 40x water immersion objective allowed the visualization, at 400x, of neuronal somata, the associated non-neuronal cells such as SGCs, and the flow of cells within the capillary vessels (Supplementary video). The analyzer and polarizer (Fig. 1a) were useful in reducing glare. Epifluorescence was used to test if a neuron expressed a fluorescent marker such as a retrogradely transported dye previously injected into the skin (Fig. 2b). It was also used to measure calcium fluxes evoked by local application of a chemical agent such as ATP, in selected SGCs that took up a calcium dye indicator topically applied to the DRG (Fig. 5).

3.2 Electrophysiological recordings of action potentials and membrane currents

A vasoconstrictor was applied by a cuff to the spinal nerve when it was necessary to block the blood flow to the capillaries of the DRG (Fig. 1c). Then, collagenase could be topically applied to the DRG to slightly loosen the neuronal somata from adjacent cells without causing bleeding. A successful blockade of blood flow produced a virtual in-vitro (bloodless) intact DRG preparation. A soma was then visually selected for its size or the presence of a marker and drawn, by gentle suction, against or just inside the mouth of a fire polished micropipette without injury (Fig. 2c and Fig. 3b). Extracellularly recorded action potentials, evoked electrically from the suction electrode or by application of natural stimuli to the peripheral receptive field, were used to characterize the axonal conduction and sensory transmission properties of the neuron for as long as desired (Figs. 2 and 3).

An intracellular (sharp) recording electrode could be used (before or after the vasoconstrictor) to measure membrane and action potential properties or changes in membrane potential in response to a topically applied chemical such as capsaicin (Fig. 2h). Alternatively, or subsequently, patch-clamp recordings were attempted after topical application of additional collagenase for removal of satellite glia and debris. For example, whole-cell patch-clamp recording under voltage-clamp could be used to characterize the voltage-dependence of activation of TTX-R sodium currents (Fig. 4). In such tests, an external solution that reduced contaminating potassium and calcium currents was continuously applied by a pipette whose tip was approximately 100 μm from the soma. However, even with solutions which reduced the magnitude of fast-inward currents, some space clamp difficulties were present, as evidenced by the relatively fast inward-current activation around −50mV. This was likely due to the cable properties of the excitable axon attached to the soma and would be difficult or impossible to space clamp without severing the axon. Nevertheless, the clamp difficulties were primarily present around threshold and the contribution of axonal currents would be relatively minor when somal currents are strongly activated, owing to the greater membrane area of the soma.

The surrounding tissue was covered by a thin plastic wrap to prevent exposure to the external perfusate which, in turn, was removed by suction.

4. Discussion

In conventional in-vivo studies, neurons of a particular type are electrically identified blindly and somewhat randomly according to whether a search stimulus can evoke action potential activity (Ritter and Mendell, 1992). The ability to record such activity is dependent, in turn, on the electrical properties and unseen position of the electrode and the damage it produces. In contrast, the present procedure offers the option of identifying the presence of a particular type of neuron prior to electrophysiological recording. For example, a neuron might be visually selected according to its size and/or the presence of a fluorescent marker expressed either by the neuron or by the glia, endothelial, or immune cells associated with the neuron. Transgenic mice offer the opportunity of visualizing one or more genetic/molecular markers in one or more cell types (Rau et al., 2009; Seal et al., 2009). Previously, intracellular recording of visualized neurons in the intact DRG, without application of collagenase, has been used only in vitro (Zhang et al., 1999) or ex-vivo with the spinal nerve still attached to the animal (Ma et al., 2003).

The capacity to block the blood flow to the DRG via the cuff, while maintaining the viability of the cells and controlling or manipulating their local chemical/ionic environment affords the possibility of performing multiple in-vitro operations in an in-vivo preparation. An advance over the prior method of complete dissociation and axotomy of neurons is the capacity to perform a controlled, graded dissociation without separation of the neuron from its peripheral target. Thus, a short application of collagenase to obtain partial loosening of neuronal somata allowed complete receptive-field characterization of the receptive field properties via the wide-mouth pipette without damage to axon or cell body (Faustino and Donnelly, 2006). Then, additional collagenase, and sometimes repeated suction by a patch pipette, could be performed to remove the glial cell to obtain a giga-ohm seal on the surface of the neuronal soma as previously done in the intact DRG, in vitro (Faustino and Donnelly, 2006; Hayar et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 1998). If desired, the same neuron can be recorded in sequence by three different types of electrode. Or, a neuron and its glial cell could be simultaneously recorded as in the intact DRG, in vitro (Zhang et al., 2009). Finally, the capacity to manipulate and to perfuse the recorded cell, in vivo, with a temperature controlled solution is not only required if a particular current is to be isolated during patch-clamp recording but also offers the chance of comparing the chemical, mechanical and thermal response properties of the soma of a neuron with those of its terminal endings.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video: Capillary blood flow and neuronal cell bodies on the surface of a rat DRG (magnification, 400x).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant NS014624. We thank Charles Fanghella for technical support on microscopy and Wendolyn Hill for technical assistance in drawing the schematic in Fig. 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baumann TK, Simone DA, Shain CN, LaMotte RH. Neurogenic hyperalgesia: the search for the primary cutaneous afferent fibers that contribute to capsaicin-induced pain and hyperalgesia. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:212–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino EV, Donnelly DF. An important functional role of persistent Na+ current in carotid body hypoxia transduction. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1076–84. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00090.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayar A, Gu C, Al-Chaer ED. An improved method for patch clamp recording and calcium imaging of neurons in the intact dorsal root ganglion in rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;173:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Druzinsky RE, Mendell LM. Properties of somata of spinal dorsal root ganglion cells differ according to peripheral receptor innervated. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:1584–96. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.5.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson SN, Crepps BA, Perl ER. Relationship of substance P to afferent characteristics of dorsal root ganglion neurones in guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1997;505(Pt 1):177–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, LaMotte RH. Enhanced excitability of dissociated primary sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion in the rat. Pain. 2005;113:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, LaMotte RH. Multiple sites for generation of ectopic spontaneous activity in neurons of the chronically compressed dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14059–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Shu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Y, Yao H, Greenquist KW, White FA, LaMotte RH. Similar electrophysiological changes in axotomized and neighboring intact dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1588–602. doi: 10.1152/jn.00855.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM. The endogenous redox agent L-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8766–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau KK, McIlwrath SL, Wang H, Lawson JJ, Jankowski MP, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, Koerber HR. Mrgprd enhances excitability in specific populations of cutaneous murine polymodal nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8612–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1057-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AM, Mendell LM. Somal membrane properties of physiologically identified sensory neurons in the rat: effects of nerve growth factor. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:2033–41. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal RP, Wang X, Guan Y, Raja SN, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI, Edwards RH. Injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity requires C-low threshold mechanoreceptors. Nature. 2009;462:651–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ZY, Donnelly DF, LaMotte RH. Effects of a chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion on voltage-gated Na+ and K+ currents in cutaneous afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1115–23. doi: 10.1152/jn.00830.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Mei X, Zhang P, Ma C, White FA, Donnelly DF, Lamotte RH. Altered functional properties of satellite glial cells in compressed spinal ganglia. Glia. 2009;57:1588–99. doi: 10.1002/glia.20872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JM, Donnelly DF, LaMotte RH. Patch clamp recording from the intact dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;79:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JM, Song XJ, LaMotte RH. Enhanced excitability of sensory neurons in rats with cutaneous hyperalgesia produced by chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3359–66. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JH, Walters ET, Song XJ. Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons induces hyperexcitability that is maintained by increased responsiveness to cAMP and cGMP. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:15–25. doi: 10.1152/jn.00559.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Lamotte RH, Grigg P. Comparison of responses to tensile and compressive stimuli in C-mechanosensitive nociceptors in rat hairy skin. Somatosens Mot Res. 2002;19:109–13. doi: 10.1080/08990220120113095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann K, Hein A, Hager U, Kaczmarek JS, Turnquist BP, Clapham DE, Reeh PW. Phenotyping sensory nerve endings in vitro in the mouse. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:174–96. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video: Capillary blood flow and neuronal cell bodies on the surface of a rat DRG (magnification, 400x).