Abstract

Purpose

To create an orientation independent, three dimensional reconstruction of the veins in the brain using susceptibility mapping.

Materials and Methods

High resolution, high pass filtered phase images usually used for susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) were used as a source for local magnetic field behavior. These images were subsequently post-processed using an inverse procedure to generate susceptibility maps of the veins. Regularization and interpolation of the data in k-space of the phase images were used to reduce reconstruction artifacts. To understand the effects of artifacts, and to fine tune the methodology, simulations of blood vessels were performed with and without noise.

Results

With sufficient resolution, major veins in the brain could be visualized with this approach. The usual geometry dependent phase dipole effects are removed by this processing, leaving basically images of the veins. Different sized vessels show a different level of contrast depending on their partial volume effects. Vessels that are 8mm or 16 mm in size show quantitative values expected for normal oxygen saturation levels. Smaller vessels show smaller values due to errors in the methodology and due to partial volume effects. Larger vessels show a bias toward a reduced susceptibility approaching 90% of the expected value. Limitations of the method and artifacts related to different sources of errors are demonstrated.

Conclusion

Susceptibility maps can successfully create venograms of the brain with varying levels of contrast-to-noise depending on the size of the vessel. Partial volume effects render this approach more useful as an imaging tool or a visualization tool although certain larger vessels have measured susceptibilities close to expected values associated with normal blood oxygen saturation levels.

Keywords: susceptibility weighted imaging, susceptibility mapping, oxygen saturation, iron measurements

INTRODUCTION

Susceptibility weighted imaging has been used for some time as a means to enhance venous signal using high pass filtered phase images (1, 2). The special image created by SWI processing relies on an asymmetric voxel aspect ratio. Therefore, when SWI is collected with high resolution isotropic data, the conventional processing will fail. To overcome this problem, we propose using a form of susceptibility mapping to produce an image of veins from SWI phase data (1). Such a map would make it easier to image venous vessels independent of their size and orientation, which we refer to here as susceptibility mapping of veins.

The ability to quantify local magnetic susceptibility is tantamount to being able to measure the amount of calcium or iron in the body whether it is calcium in breast (3) or iron in the form of non-heme iron (such as ferritin or hemosiderin) or heme iron (de-oxyhemoglobin). In the last few years, there have been a number of papers discussing different methods for doing this using a fast Fourier transform approach (4–10). All of these methods are based on the simple expression in k-space for analyzing distant dipolar fields from a given source of susceptibility distributions first given by Deville et al (11) in 1979. One of the methods utilizes the inverse of the Green’s function (8). This is, however, fraught with difficulties as it is an ill-posed problem due to singularities in the inverse of the Green’s function. To this end, different groups have tried regularization or multiple scans acquired with the object being rotated between scans (8, 9). In this paper, we show that good quality magnetic source images or susceptibility maps (SM) of the veins in the brain can be obtained when the inverse is regularized and other sources of phase noise are removed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inverse Filter Regularization

To reconstruct the susceptibility distribution, a regularized inverse filter, g−1(k), was applied to the Fourier transform of the high pass filtered phase image. The forward filter is defined by:

| [1] |

where kx, ky, kz denote the coordinates in k-space and |k|2 = kx2 + ky2 + kz2. The filter g(k) goes to zero when 2kz2 = kx2 + ky2, making g−1(k) undefined (we refer to these kz values which satisfy this equation as kzo). Hence, to reconstruct the susceptibility distribution, a regularized version of the inverse filter g−1(k) is applied to the Fourier transform of the unwrapped / high pass filtered phase image, φ(k). It should be noted here that “k-space” in this paper refers to the Fourier or frequency domain of unwrapped/high pass filtered phase images (i.e., obtained by directly taking their discrete Fourier transform), rather than the usual acquired k-space data in MRI.

In our approach to this problem, we regularize g−1(k) as follows. First, we restrict g(k) to have a minimum value a so that its inverse remains well defined. That is, for any k where | g(k) | < a, g(k) is set to −a or a depending on the sign of g(k) (i.e., g−1(k) is set to a minimum of −1/a or a maximum of 1/a). This first step prevents g−1(k) from becoming too large and enhancing noise points near singularities. Second, the inverse, g−1(k), is brought smoothly to zero as k approaches kzo such that the discontinuity at kz = kzo is removed. This smoothing is accomplished by multiplying g−1(k) by α2(kz) where α(kz) is defined as:

| [2] |

where kz is the z component of that particular point in k-space, kzo is the point at which the function g−1(k) becomes undefined and Δkz is the k-space sampling interval along the z direction. This filter starts to reduce the maximum of g−1(k) starting b pixels away from the singularity and rapidly brings it to zero at the singularity. The choice of b is discussed below. Denoting the regularized inverse filter by g−1reg(k), the susceptibility map for the 3D data set is calculated via:

| [3] |

where φzf-proc(k) is the Fourier transform of the high pass filtered phase φzf-proc(r). The subscript “zf-proc” refers to the high pass filtered, zero filled phase images as described in references (1,2). Note that, we impose the condition g−1reg(kx=0, ky=0, kz=0) = 0 in the regularized filter. This in-turn implies that the quantification is only valid for relative susceptibility differences, i.e. only Δχ, and not for absolute χ values.

Selection of a and b

The choice of threshold value is particularly important in determining the quality of the susceptibility map (SM). The choice of threshold a for g(k) determines to a large degree the amount of streaking that will occur. The reason for this is based more so on the discretization errors and ill-posedness of this inverse approach. To find an appropriate threshold value, phase due to a cylinder of diameter 8 voxels perpendicular to the main magnetic field, was simulated (for simulation details see the next section). A Δχ of 0.45 ppm, B0 of 3T and TE of 5ms was assumed. Susceptibility maps were generated using g−1reg(k) in Eq. [3] for varying a values. In the resultant SM, mean and standard deviation (SD) of susceptibility values inside the vessel were measured. The mean squared error of the values outside the vessel was also used to measure artifact levels in the background. The value of a was varied from 0.05 to 0.30 in steps of 0.05.

Although setting the threshold value, a, prevents g−1(k) from becoming ill-defined, it creates an abrupt step-like discontinuity in the behavior of g−1(k) in the neighborhood of kz = kzo. To avoid these abrupt transitions, we use α(kz), defined with a parameter b, to bring the inverse filter smoothly to zero. When | g(k) | < a, the filter smoothly reduces the value of g−1(k) starting b pixels away from the singularity and rapidly brings it to zero at the singularity. The value of b in turn depends on the value of a since:

| [4] |

where kza is the kz coordinate value where |g(k)| = a, for a given kx and ky corrdinates. One can now rewrite Eq. [2] as

| [5] |

Simulations

To study the effects of partial-voluming, noise, phase aliasing and high pass filtering of phase on the susceptibility mapping process, we simulated the phase of cylinders of varying size, oriented perpendicular to the main magnetic field. The susceptibility maps of these cylinders were generated using the regularized filter g−1reg(k) with an a value of 0.1. In these simulations, instead of calculating the phase of each of the cylinders on discrete grid points directly using the analytic formula for an infinitely long cylinder, we performed a process analogous to the MRI image acquisition. We start by simulating the cylinder and its phase on a large grid consisting of a 4096 × 4096 matrix. We then obtained the lower resolution version of the phase by taking the central part of its Fourier transform and applying an inverse Fourier transform to this central k-space matrix, say 512 × 512 for isotropic voxel size. So, for example for a cylinder that is 64 voxels wide in a 512 matrix size; this started out as a 512 voxels wide cylinder in the 4096 matrix. In that sense, if the 512 × 512 matrix represents 0.5 × 0.5 mm resolution, then we are using a resolution of 62.5µm to first sample the object discretely and by taking the central k-space, we mimic a more analytic Fourier transform representation of the final resolution’s k-space signal. Data generated in this manner exhibits the usual experimental artifacts such as Gibbs ringing and partial volume effects not seen with an analytical solution. We refer to these input phase images in this paper as the ‘simulated phase’ images. All simulations assumed a Bo value of 3T and Δχ of 0.45 ppm and a cylindrical geometry perpendicular to the main magnetic field is considered. To estimate the affect of partial voluming, cylinders with different radii (r = 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 voxels), perpendicular to the main magnetic field were simulated, each with voxel aspect ratios of 1:1, 1:2 and 1:4. For example, a phase image with a voxel aspect ratio of 1:2 is generated by inverse Fourier transforming only the central 512 × 256 points of the original 4096 × 4096 point k-space (and for 1:4 aspect ratio, it is the central 512 × 128 points). Subsequently, their corresponding susceptibility maps were generated and the mean and standard-deviation of the resultant susceptibilities were measured. Two echo times, TE = 5ms and TE = 20ms, were considered for this simulation to study the affect of phase aliasing on the estimated susceptibility values. While TE = 5ms does not lead to any phase aliasing, the phase image at TE = 20ms has considerable phase aliasing. Different voxel aspect ratios here are meant to represent the ratio between in-plane to through-plane voxel dimensions for typical transversely orientated SWI data. The effect of high pass filtering the phase data on the susceptibility maps was also simulated and studied. Again, simulated phase images of cylindrical geometry with radii of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 were considered. Homodyne high pass filters (1, 2) of size 16, 32 and 64 were applied on these phase images before being used for susceptibility mapping process. The mean and standard deviation of the susceptibility value for each simulated case were measured.

To study the effect of noise in phase images on the noise in the resultant susceptibility map, we simulated a complex data set for a cylinder of diameter 8 voxels with Gaussian noise added. Noise was added to both real and imaginary channel images such that the resultant signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) in the magnitude image was 40:1, leading to a standard deviation in the phase image of 0.025 radians. After performing the process outlined in Eq.[3] to get the susceptibility map, this phase noise will be altered in some manner by the susceptibility mapping process. We measure the noise mean and standard deviation outside the object in the SM map.

In vivo MR Data Collection and Processing

To reconstruct a susceptibility map of venous vessels with minimal artifacts, the following steps were carried out: i) collect an isotropic high resolution SWI data set, ii) high pass filter the phase images, iii) interpolate k-space, iv) remove spurious phase noise sources from the phase images and v) regularize the data. These steps are described in more detail below.

Susceptibility weighted imaging sequence, which is a high resolution 3D gradient echo sequence with velocity compensation in all 3 directions was used for data collection. The sequence parameters used were TR=26 ms, flip angle 11° and bandwidth 80 Hz/pixel in the read direction. We collected images with 0.5mm isotropic resolution at 4T field strength at three echo times of 11.6ms, 15ms, and 19.2 ms and with a matrix size of 352 × 512 (phase × read directions respectively). A total of 88 slices were collected. The k-space data were then truncated in the slice select direction to mimic 1mm and 2mm thick slices and zero filled to interpolate the images to 0.5mm slice thickness in order to create maximum intensity projections (MIPs) that would match when comparing MIPs over the different resolution reconstructions. The images were acquired in absolute transverse orientation without any angulation to coronal or saggital direction.

Phase data were high pass filtered using an n × n central low pass filtered image (1, 2) divided into the original complex image. This gives a homodyne or effective high pass filtered phase image, φ(x), which removes most of the low spatial frequency phase.

In order to keep the field of view in x, y and z directions at the aspect ratio of 1:1:4, k-space was interpolated by zero filling the phase images, φzf-proc(r), in all three directions to a 512 × 512 × 128 matrix size. This 3D image set, φzf-proc(r), was then Fourier transformed to create a k-space data set φzf-proc(k). Zero filling the initial input phase images to a larger matrix also helps in reducing the pseudo ghosting that gets introduced in the SM due to artifacts associated with the Fourier transform and application of the inverse-filter. Note that ghosting referred to here, is a form of structural-aliasing and in this sense refers to the replication of information in the image domain when the data are under-sampled. Elsewhere in this paper we use the term aliasing to refer to phase information that has aliased back into the interval [−π,π).

Noise in the non-tissue region in the phase images was removed, by using a complex thresholding (12) approach on the magnitude image, followed by a skull stripping algorithm.

The regularized inverse filter discussed earlier was applied to the Fourier transform of the high pass filtered phase image.

To assess the sensitivity of SM maps to changes in venous oxygenation levels, we compare the susceptibility map data before and after ingestion of 200 mg caffeine (NoDoz, Bristol-Myers Squibb, NY, NY) for a normal healthy male volunteer. The data was acquired at 3T on a Siemens VERIO system with a voxel size of 0.5 × 0.5 × 2mm, flip angle of 15° and a bandwidth of 100Hz/pixel at an echo time of 20ms. SWI images were acquired before the ingestion of caffeine and about 50 minutes after the ingestion of caffeine. All human data was collected in accordance with the local institutional review board guidelines.

RESULTS

Simulations

There are six major sources of error in creating venous susceptibility maps: i) errors in the inversion process, i.e. those due to g−1reg(k) itself; ii) voxel aspect ratio affects (i.e., partial voluming); (iii) aliasing in input phase images caused by longer echo times; (iv) errors caused by high pass filtered phase data; v) errors due to discrete sampling in MRI and vi) thermal noise in the phase data. We consider each of these in the following paragraphs.

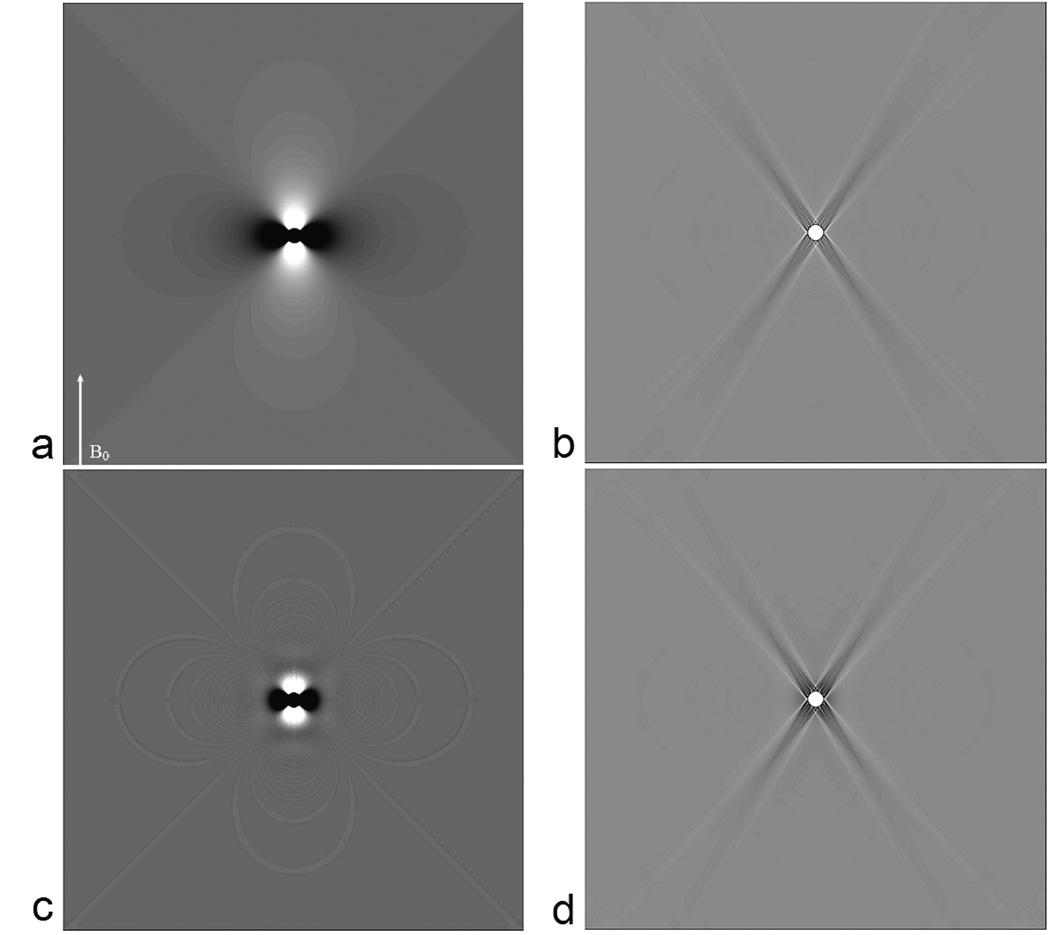

Even with regularization, and with no thermal noise considered, the inversion process is not perfect. In this case, it depends on the choice of a. In Table 1, we show the root mean squared error (RMSE) both inside and outside the cylinder along with the percent error of the quantified susceptibility with respect to the input value of 0.45 ppm. RMSE outside the cylinder is taken only from an annular region centered around the cylinder with a thickness of 20 voxels (i.e., an annular region defined by a n inner-radius of 4 and an outer-radius of 24 voxels (beyond which the error is small)). The errors inside the object seem to be minimized with at a = 0.15. Practically, a choice of a anywhere between 0.05 to 0.2 appears to provide a reasonable estimate for the susceptibility without causing much noise or ghosting artefacts outside the object. Nonetheless, for the sake of consistency, we have used an a value of 0.1 for all the results presented in this manuscript. To appreciate the distribution of errors we show the phase of a cylinder perpendicular to the field and its corresponding susceptibility map in Figure 1a & b respectively. As we can see, within the susceptibility maps, the errors can be divided into three regions: a) within the object itself, b) errors along the streak artifacts corresponding to the cone of singularity in g−1reg(k) in k-space, i.e points in the neighborhood of kz=kzo where | g−1(k) | > 1/a. and c) errors outside these regions. Notice that while the cone of singularity in g−1(k) is defined in k-space at kz = kzo (i.e., where 2kz2 = kx2+ ky2), the streak artifacts in the image domain occur along z2 = 2x2+2y2.

-

Errors outside the object, along the streak artifacts: Along the streak artifacts, (see Figure 2), the error in the susceptibility map measured in a region of interest the size of the vessel, is within ±85% of the input susceptibility value in the first few voxels close to the boundary of the cylinder and drops off rapidly within the next few voxels to less than 10% and then slowly after that to less that ±0.25% at the edge of the field-of-view. Since the errors outside the object scale with the input susceptibility value of the vessel, the errors here are quoted as its percentage.

Errors outside the object and the streak artifacts: Outside of these two regions, the errors in the susceptibility maps (basically the systematic ‘noise’ generated outside the object due to the susceptibility mapping process) is again close to −45% in the immediate boundary of the object and drops off rapidly to less than −0.25% for most of the field-of-view. One important point to note is that this near vessel error is negative so that when maximum intensity projections of the susceptibility maps are taken to display the veins as contiguous objects, this error is not visually apparent.

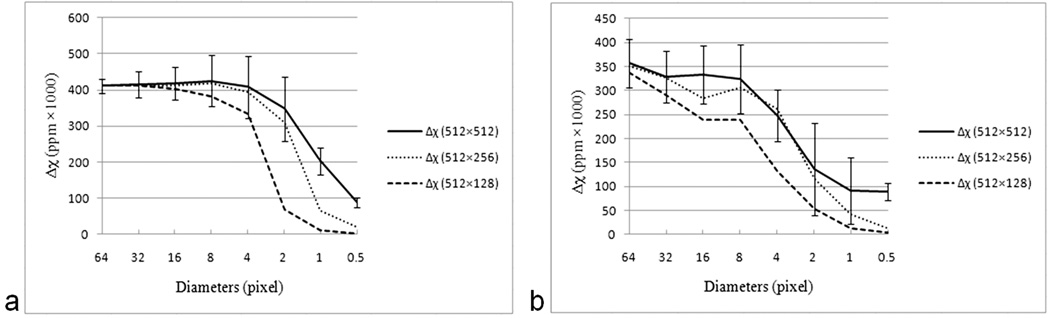

Errors within the cylinder: Figure 3a plots the mean and standard deviation of the measured susceptibility values across different radii cylinders and different voxel aspect ratios, for an input phase at TE = 5ms. With an isotropic resolution and a vessel diameter greater than 8 pixels, the susceptibility is underestimated by roughly 11% (with respect to the input Δχ value of 0.45 ppm). For objects smaller than 4 pixels, again the estimated susceptibility drops but this time more drastically as the error here depends on partial volume effects. For a diameter of two pixels, the susceptibility is already down to two thirds of its expected value and after that, it heads rapidly toward zero with the amount of signal in the susceptibility map depending on the volume of the vessel occupying the pixel. Furthermore, since through plane resolution is often less than in-plane resolution, it is interesting to look at the results for different voxel aspect ratios. It is not surprising to find that as the slice thickness to vessel diameter ratio increases, the estimates for susceptibility get worse due to increasing partial voluming. With a voxel aspect ratio of in-plane to slice thickness of 1:1 or 1:2, the susceptibility is estimated reasonably well (Figure 3a), but for an aspect ratio of 1:4, even for an object that is 4 pixels in diameter, the estimated susceptibility is beginning to significantly deviate from the actual susceptibility value.

Longer echo times can lead to signal loss and aliasing in the phase data. This leads to an effective increase in the size of the vessel and hence a reduction in the predicted susceptibility. Comparing the TE = 5ms susceptibility data in Figure 3a with the TE = 20ms data in Figure 3b, we can see that all the susceptibility values are lower in the latter case and this reduction becomes more dramatic as the vessel size decreases. This is caused by the phase aliasing that occurs at the longer echo time of 20ms which in turn affects the expected diameter of the vessel and the susceptibility. Furthermore, with aliasing, the affect of vessel partial-voluming due to non-isotropic voxel dimensions follows a more drastic trend than that seen at TE 5 ms.

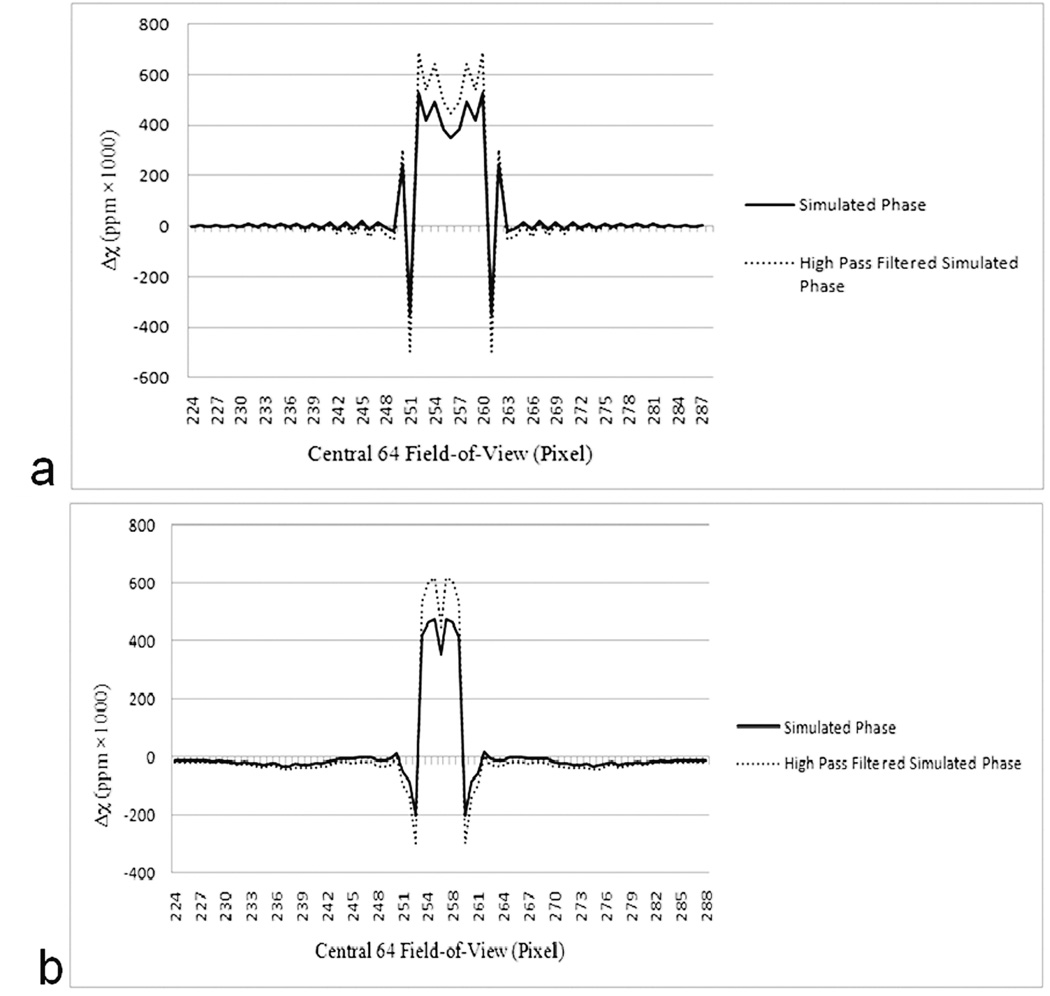

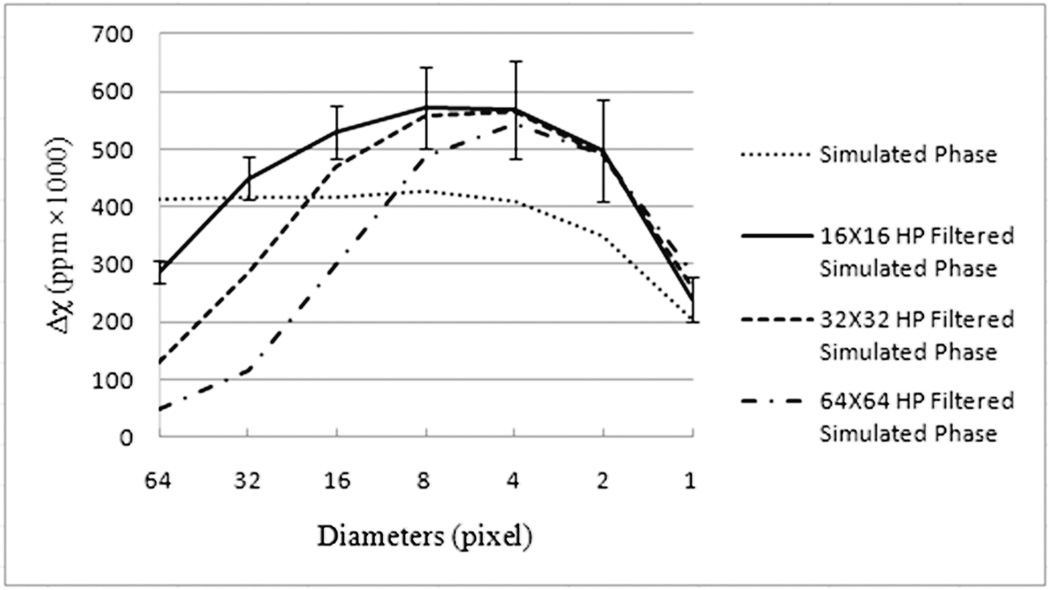

High pass filtering: Figure 4 shows the affect of phase high pass filtering on the measured susceptibility values within the cylinders of different radii. Affects of filter sizes, 16 × 16, 32 × 32 and 64 × 64 are plotted. As expected, different errors are seen for different filter sizes. For the filter size of 16 × 16, the susceptibility of the vessels between 2 and 32 pixel diameter, lies within ±30% of the input value of 0.45ppm. However, outside this diameter range, for vessel diameters 1 and 64, the susceptibility value is underestimated. For the vessel with diameter 64 voxels, under-estimation of susceptibility value is primarily due to loss of phase information within the vessel, as a filter size of 16 × 16 removes most spatial features with an extent larger than 32 voxels. For diameters between 2 and 32 pixels, the susceptibility values are over-estimated. This over-estimation of susceptibility might be expected, as the high pass filter changes the nature of the phase at the edge of the object and more so far away from the object, making it appear to rise/fall faster near the edge of the cylinder. For a diameter of one pixel, the susceptibility is underestimated with respect to the expected 0.45ppm due to partial voluming, but the estimated value is still higher compared to the value in Figure 3a with no high pass filtering. Similarly, for a filter size of 32 × 32, the susceptibility values of diameter 64 and 32 vessels, and for filter size 64 × 64, susceptibility values of diameter 64, 32 and 16 vessels are under-estimated, again primarily due to a loss of phase information within the cylinder due to high-pass filtering. Figure 2 (dashed lines) shows the affect of high pass filtering on the ‘noise’/errors outside the object and along the streak artifacts. Apart from over-estimating the susceptibility value inside the cylinder, it also causes a proportional increase in the error around the boundary of the object. However, as noted above, the error at the edge of the vessel is negative so that when MIPs are taken of the veins to display them as contiguous objects, this error does not contribute to the final MIPped image of the veins.

The discretization errors can lead to improper representation of the object in the phase images because of partial volume effects. This explains in part the errors seen in Figure 3 as object size decreases. In principle, if the measured diameter of the object (dm) is compared to the actual input value (da) and used to predict the area change, then we can predict the magnetic moment rather than the susceptibility. Since the magnet moment is related to the cross sectional area of the vessel times the susceptibility, the corrected value, Δχactual, can be calculated from Δχmeasured (dm/da)2.

The systematic errors described above are distinct from the effects of thermal noise. There we see that an SNR of 2.5% in the magnitude image leads to a thermal noise or error in the phase image of 0.025 radians. If the inverse filter did not affect the phase noise at all, the noise error in the susceptibility map would be expected to be around 0.0063ppm. However, the inverse filter amplifies the noise near the streak artifacts and this leads to noise outside the magnetic source (the cylinder) of 0.035 ppm in the susceptibility map in regions outside the streak artifacts (Figure 5). This systematic error from thermal noise is independent of the object susceptibility value and hence errors are quoted in ppm rather than as percentage of the object susceptibility.

Table 1.

Root Mean Squared errors in susceptibility maps

| a | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) outside cylinder (units =1000 × Δχ in ppm) |

RMSE inside cylinder (units =1000 × Δχ in ppm) |

% Error in mean Δχ value within the cylinder |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 60.8 | 93.0 | −3.4 |

| 0.1 | 55.7 | 73.2 | 3.5 |

| 0.15 | 54.4 | 68.5 | 9.6 |

| 0.2 | 53.6 | 82.1 | 15.9 |

| 0.25 | 52.8 | 108.3 | 22.8 |

| 0.3 | 51.1 | 141.6 | 30.8 |

Root Mean Squared errors in susceptibility values, measured within and outside a cylinder of 8 voxels diameter, for different threshold values a. Errors outside the cylinder were measured within a concentric annular ring with an inner radius = 4 and outer radius = 24 voxels. Also shown is the corresponding % error in quantified mean Δχ with respect to an expected 0.450 ppm (the error defined as (0.45 - χ)). Errors outside the cylinder decrease with increasing a value where as for the error within the cylinder, an a value of 0.15 seems to be optimal. However, in general a threshold value of 0.05 to 0.2 could be used depending on the contrast needed in the SM map.

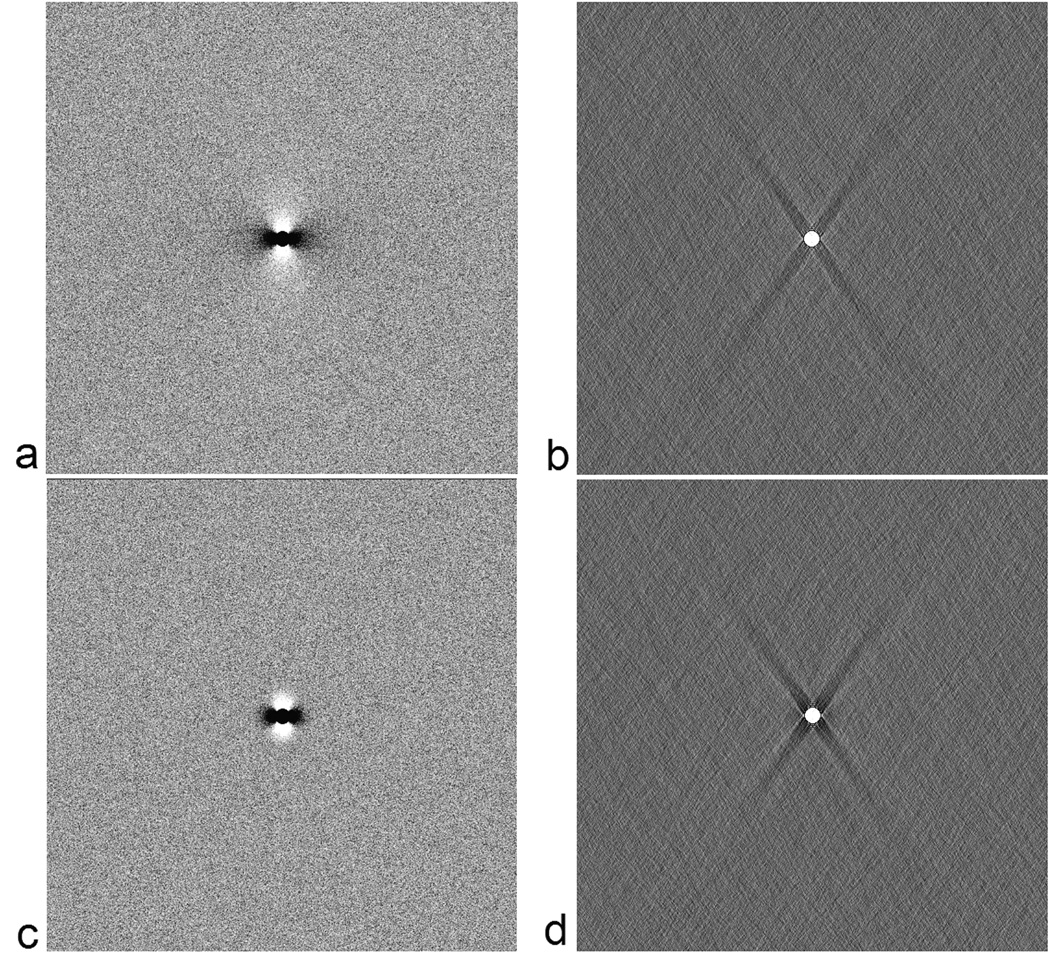

Figure 1.

The original phase at T E = 5ms (a), high pass filtered phase (c) and their corresponding susceptibility maps (b) and (d) for a cylinder with a diameter = 8 pixels. Streak artifacts are clear in both (b) and (d). The arrow in (a) indicates the direction of B0.

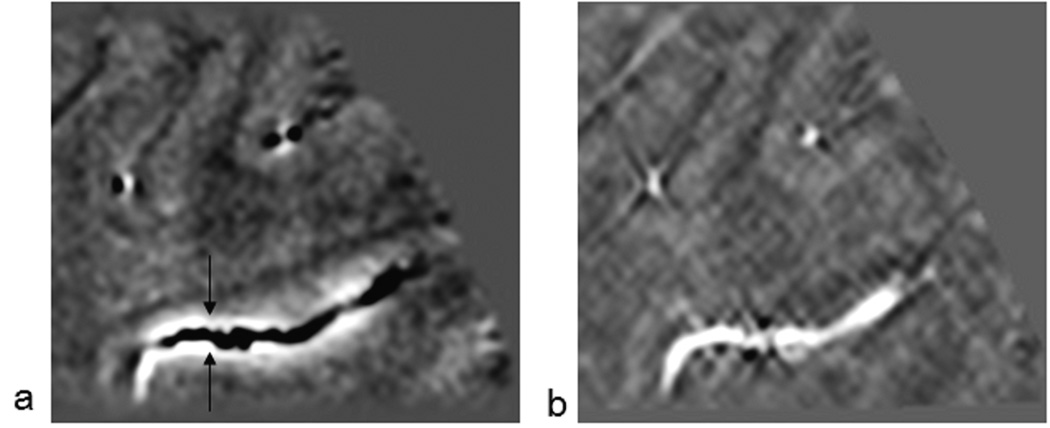

Figure 2.

Profile plots along the streak artifacts (a) and along the x-axis (b) in the central 64 × 64 pixels of the 512 × 512 image. The profiles represent susceptibility values inside the object and how the error decays toward the edge of the field-of-view. Errors near the boundary of the object are large. The dotted lines show errors in the susceptibility maps from the high pass filtered phase images (the filter size was 32 × 32). The diameter of the cylinder is 8 pixels.

Figure 3.

Plots of the measured susceptibility as a function of both diameter of a vessel and the aspect ratio for TE = 5ms (a) and TE = 20ms (b). The 512 × 512 simulation (created from the original 4096 × 4096 data) represents a voxel aspect ratio for an in-plane resolution to slice thickness of 1:1. The 512 × 256 simulation represents an aspect ratio of 1:2 and the 512 × 128 simulation represents an aspect ratio of 1:4. Note that the susceptibility values are multiplied by 1000 for display purposes. Errors bars are shown for the isotropic case to demonstrate the systematic error. The errors in the 1:1 and 1:2 aspect ratios are similar and the errors in the 1:4 case are somewhat larger. Mean and standard deviation of susceptibility values were measured by zooming objects twice for cylinders with diameter 2, three times for a diameter of 1 and four times for diameter of 0.5 voxels. While no phase aliasing is present for (a), aliasing at TE 20 ms lead to an additional effect on the susceptibility quantification in (b). The input susceptibility value for all simulations was 0.45 ppm (i.e., 450 in the plot).

Figure 4.

Plots show the affect of high pass filtering on the quantified susceptibility values. Results for 3 filter sizes Nf (16 × 16, 32 × 32 and 64 × 64) are shown here. Applying a high pass filter leads to a major loss of phase information in objects that are larger than (N/Nf) voxels, where N is the matrix size and Nf is the filter size along a given direction. For objects smaller than (N/Nf), high pass filtering modifies the phase at the boundary of the object such that the susceptibility values are over-estimated.

Figure 5.

Thermal noise added to the simulated phase of a cylinder with diameter = 8 voxels, oriented perpendicular the main magnetic field (a). Following parameters were assumed: susceptibility = 0.45 ppm, Bo = 3T, and TE = 5 ms. Gaussian noise was added to the real and imaginary channels such that magnitude SNR was 40:1 resulting in thermal noise in the phase image of 0.025 radians. Corresponding susceptibility map (b). The SNR in this image is measured outside the streak artifacts. The noise in these areas increases to 0.035 ppm (instead of the expected 0.0063ppm corresponding to a phase standard deviation of 0.025 radians) independent of the susceptibility of the cylinder. The susceptibility value inside the cylinder is 0.42 +/− 0.067ppm. High pass filtered phase image (64 × 64 central filter) (c) and the corresponding susceptibility map (d). The susceptibilitgy value inside the cylinder is now increased to 0.46 +/− 0.075 ppm. This is caused by the high pass filter effect on the phase. Note there is a negative error in susceptibility around the cylinder as seen in figures 1 and 2.

Susceptibility Maps of the in vivo Dataset

In the following material, we review the results of the implementation of the susceptibility mapping process as applied to an in vivo data set. First, we show how a vessel changes its phase behavior as it courses through the brain making different angles to the main magnetic field (Figure 6a). Using the conventional SWI processing here would enhance the veins parallel to the field but would incorrectly enhance the outside of the veins perpendicular to the field. After the susceptibility mapping process (Figure 6b), the vein appears as one contiguous object. A second example of this is given in the simpler in-plane case where larger veins show a clear dipole effect (Figure 7a). Again the susceptibility map shows a bright vessel along the entire path (Figure 7b), and the negative Gibbs ringing effect can also be seen.

Figure 6.

A sagittal cut demonstrating the change in phase at TE = 19.2ms, as a vein courses through the brain (a). For proper visualization of the whole vessel section, phase from 2 saggital slices (i.e., total thickness 1mm) was combined. In the phase image, the dipole effect is clearly seen with the vessel appearing dark in the phase image when perpendicular to the field and bright when parallel to the field. The distance from the top of the vessel (upper arrow) to the bottom of the vessel (lower arrow) is 7 slices (3.5mm). The fact that the phase is clearly seen in one slice with the correct sign suggests that the vein is on the order of one or two pixels in diameter (i.e., 0.5mm to 1mm). The same vein shown from the corresponding susceptibility map (b). Clearly, most of the dipolar phase around the vessel is removed and susceptibility of the vessel is highlighted through out, independent of its orientation with the main magnetic field.

Figure 7.

High pass filtered phase image showing the dipole effects for the TE = 19.2ms case (a). Corresponding susceptibility map (b). Note there is a small negative band at the edge of the major vessels as also seen in the simulations, but overall the vessels are clearly highlighted without a varying dipole effect obscuring vascular information.

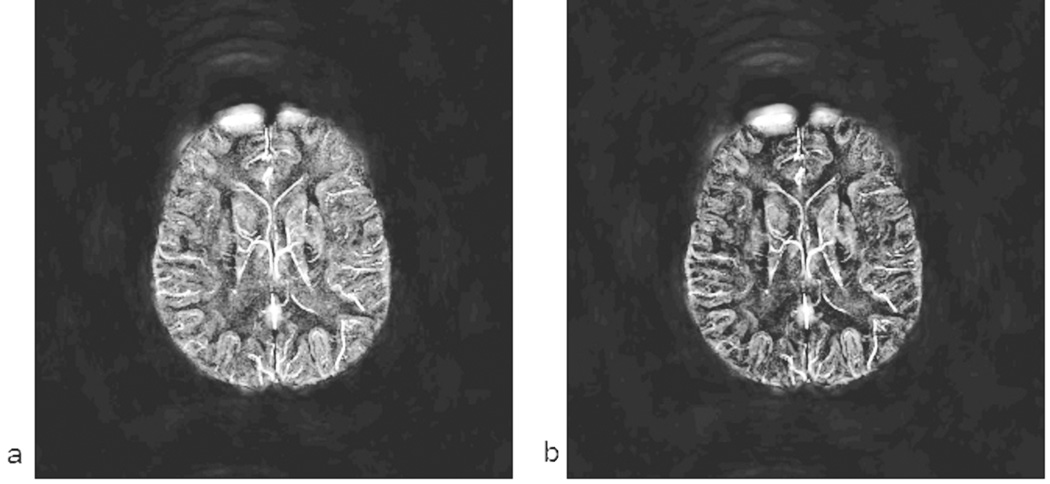

Since we are interested in displaying the susceptibility map of the veins, we present next an example set of susceptibility maps to compare with the original phase data. In Figure 8a, we show an MIP of the phase (from a right handed system) with 0.5mm isotropic resolution with an echo time of 19.2ms. The vessels are clearly shown with reduced intensity. The dipolar effect with the opposite polarity in phase can be seen on the outside of the vessels. In Figure 8b, 8c and 8d, we show the corresponding susceptibility maps for TEs of 11.6ms, 15ms and 19.2ms respectively. From the venous vessel perspective, these images from different echo times are almost identical to each other.

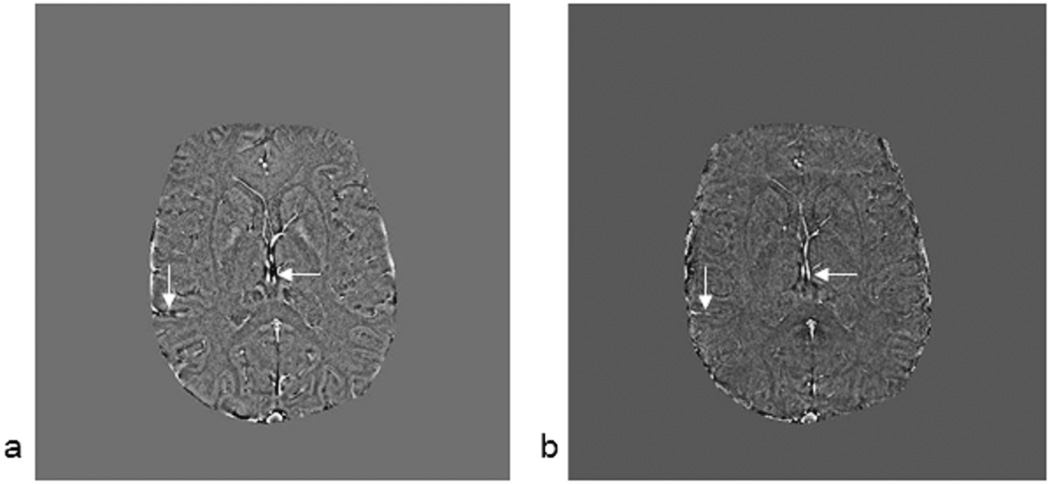

Figure 8.

mIP (minimum Intensity Projection) over 16mm (32 slices) of the phase images collected at TE = 15ms (a) along with the corresponding susceptibility maps from TE = 11ms (b), TE = 15ms (c) and TE = 19.2ms (d) phase data. Phase data were filtered with a 64 × 64 central filter. The image in a represents minimum intensity projection (mIP) over 16mm for a right handed system and all the corresponding susceptibility maps are MIPped over the same 16mm.

There are a few key observations to be made here. First, the image with the shortest echo time is the most noisy as it has much less phase information i.e., less phase-SNR. The phase-SNR here refers to where, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, ΔB is the field perturbation and σphase is the phase standard deviation for a given imaging experiment which relates to magnitude SNR as σphase = 1/SNRmagnitude. Second, the contrast between gray matter and white matter improves at longer echo times. Third, the smaller vessels become more visible and better defined at longer echo times because there is more phase information available outside the vessel. Quantitatively speaking, all of the above points are related to the initial SNR in the phase image (unlike magnitude SNR, phase SNR actually increases initially with increasing TE, so long as T2* loss is not significant and there is no phase aliasing). The higher this phase SNR, the better the corresponding susceptibility map image. Fourth, the heavy air/tissue interface artifacts present in normal SWI data are also present in the susceptibility map data. This can be seen from the very bright area in the right frontal part of the brain which could have been manually removed, but it is left in the figure to demonstrate this potential problem. Fifth, the original phase MIP shown in Figure 8a sometimes shows small vessels better than the susceptibility map data and sometimes the susceptibility map data shows better images of the vessels.

To validate that the results for the vessels were almost independent of TE, we measured the susceptibility in three large veins (Table 2). The largest vein had a susceptibility close to the normal expected value for the venous blood’s susceptibility of 0.45ppm, (see below for further explanation). The mean values for the different echo times lay within ten percent of the means despite the large variance. The large variance for each individual measurement was caused, in part, by a broad distribution of values since the region of interest was drawn to cover the entire vessel. When only the central part of the vessel was used, the standard deviations were much smaller.

Table 2.

Susceptibility values of left and right thalmostriate vein and the vein of Galen

| TE\Vein | V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11.6 ms | 278/78 | 289/62 | 435/70 |

| 15 ms | 331/98 | 303/85 | 461/163 |

| 19.2 ms | 323/90 | 280/64 | 434/119 |

Mean and standard deviation for the susceptibility values of three veins (in ppm × 1000) chosen from the 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 isotropic voxel data shown in Figure 8. V1 is for the left thalmostriate vein, V2 for the right and V3 for the vein of Galen. There is not much variation of susceptibility value with echo time, as would be theoretically expected.

Practically these isotropic scans take a long time to collect and have limited coverage. If parallel imaging is used it would be possible to reduce the scan times by a factor of 2 to 4. Therefore, the next step is to see if reasonable susceptibility maps can be derived from slices that are 1mm thick (Figure 9a) or 2mm thick (Figure 9b) as are acquired today in most SWI applications. Figure 9 shows that the thicker slices have better SNR but poorer contrast for displaying the veins. Although a few vessels have begun to become less defined with 1mm thick slices, there is a much greater loss of small vessel information in the 2mm slices. However, the thicker the slice, the better the gray-matter/white-matter contrast. For the vein of Galen, the susceptibility values remain essentially unchanged close the expected value of 0.45 ppm (see the following discussion).

Figure 9.

Thicker initial slices of 1mm (a) or 2mm (b), projected (MIP) over the same thickness as in figure 8, show the pros and cons of susceptibility mapping for lower resolution images. The thicker slice images were created from the original 0.5mm isotropic data so there is no misregistration between the images in Figure 8 and here. Note that the thicker the slice the better the SNR (especially for the gray matter and white matter) but the less clearly small vessels are seen. This is because the phase information in the voxel is now corrupted by integration of the complex signal across the slice.

The expected value of the susceptibility difference between a venous vessel and surrounding tissue, assuming a normal hematocrit of 0.45, an oxygen saturation of 0.55 and a susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, χdo, of 2.26ppm is 0.45ppm in SI units (13). For display purposes, the susceptibilities are scaled by 1000, so the numbers quoted in the figures and tables should be on the order of 450. As shown in Figure 3, as the slice thickness increases (i.e., the aspect ratio changes from 1:1, to 1:2 to 1:4) relative to the cylindrical objects, a reduction in the effective susceptibility is expected. For the thicker slices, the peak susceptibility drops to 0.41ppm for 1mm thick slices, and to 0.30 ppm for the 2mm thick slices showing that the partial volume effect is degrading the contrast in the images.

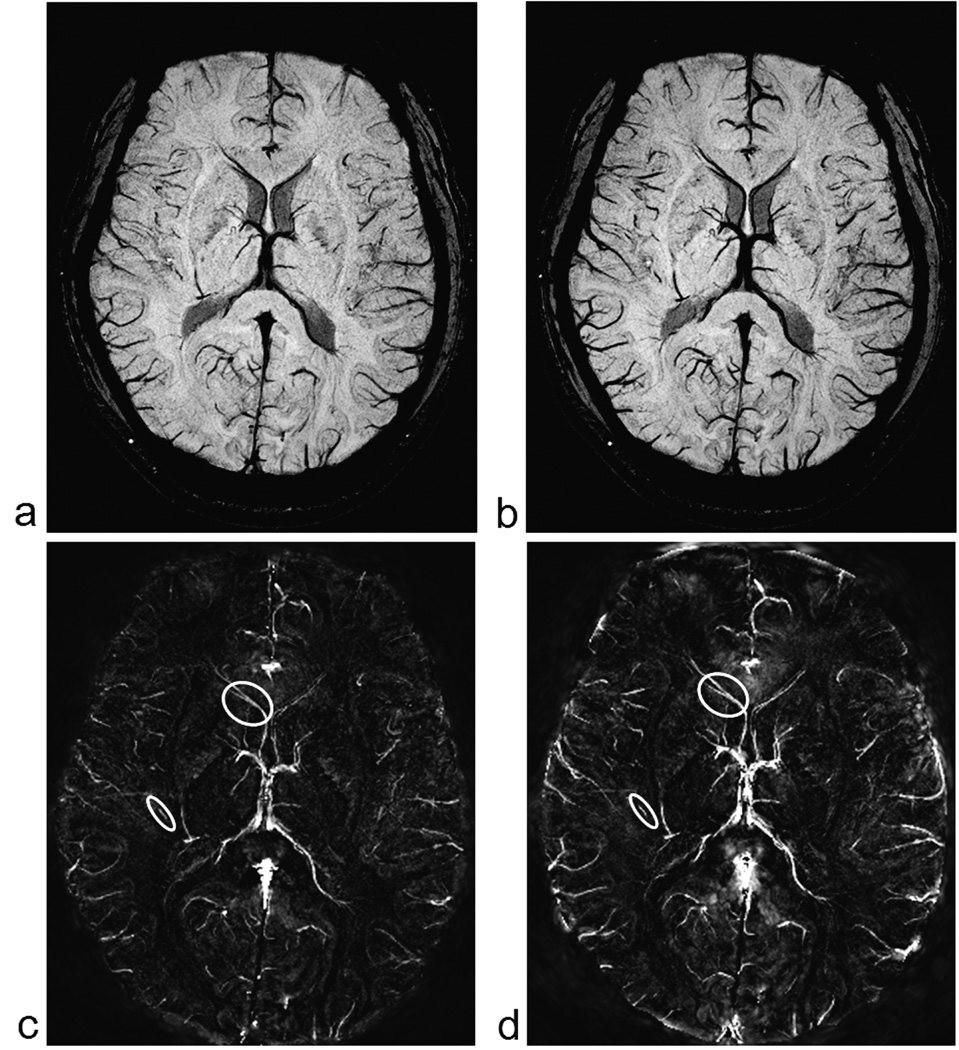

To demonstrate that at least, relative quantitative information is available from the in-vivo susceptibility maps, we measure the susceptibility in the major veins pre- and post injection of 200mg of caffeine in a healthy volunteer. Figure 10, shows the projection of the data over 4 slices (8 mm), for both before and after ingestion of 200 mg of caffeine. There is a clear increase in the susceptibility of venous blood, as can be seen from the brighter venous vessels in Figure 10d, indicating an increase in deoxyhemoglobin levels post caffeine administration. The susceptibility values in the thalamostriate vein increased from 0.121 ± 0.007 to 0.166 ± 0.008 ppm while that in the smaller veins increased from 0.095 ± 0.006 to 0.122 ± 0.007 ppm. Figure 10c and 10d indicate the vessels from which measurements were made.

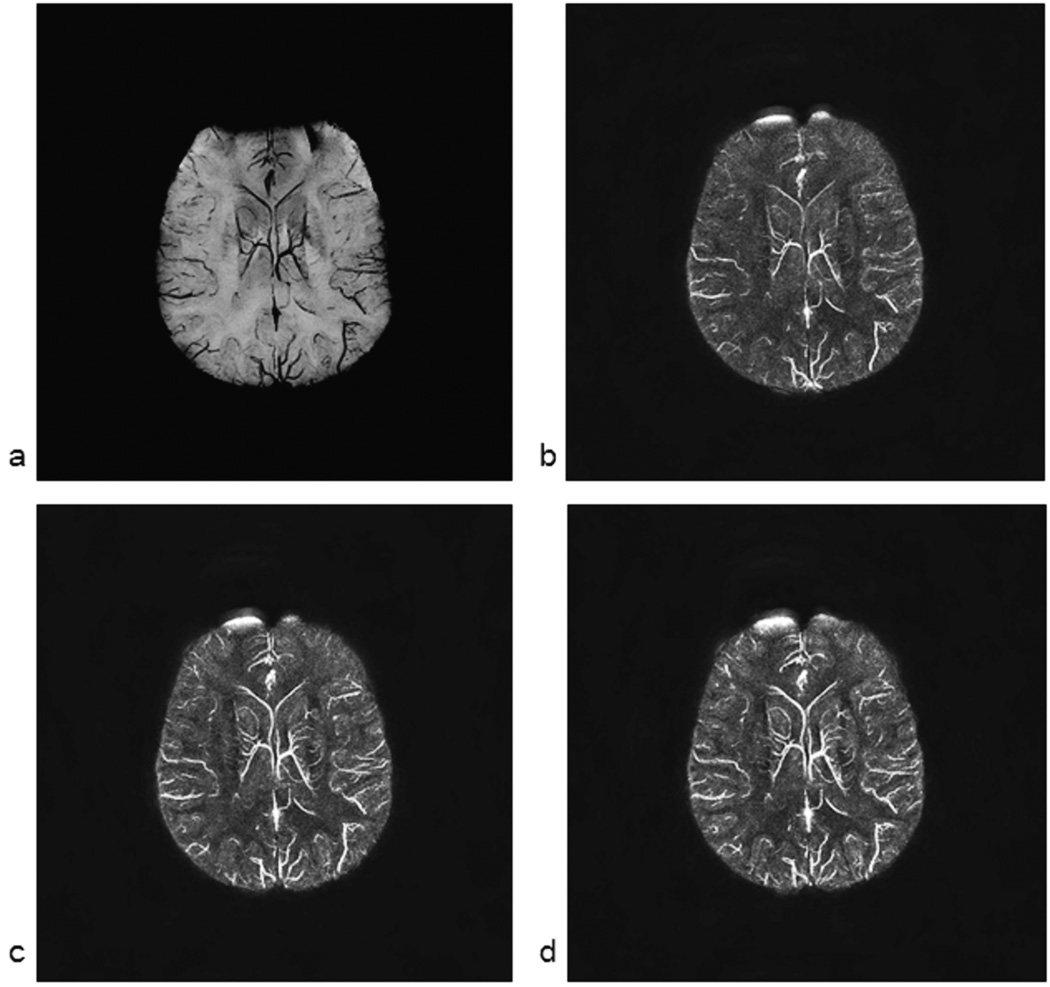

Figure 10.

Minimum intensity projections (mIP) of SWI images pre (a) and post (b) caffeine administration (8mm thick sections). Corresponding susceptibility maps pre (c) and post (d) caffeine. A thalamostraiate vein and a small vein are shown within the circles. It is in these regions where the oxygen saturation measurements were made. Note that images (c) and (d) are set to the same intensity-window levels to have a fair comparison. We can clearly see the overall enhancement of the venous structures in the post-caffeine image (d). Similarly, window levels for images (a) and (b) are also set at the same values for appropriate visual comparison.

DISCUSSION

Effects of Inverse Filter Regularization

The basic concept of using a simple Fourier transformation method to predict the magnetic field distribution from a given susceptibility distribution was described first by Deville at al (11). Since then a number of papers have used this simple k-space filter to predict the magnetic field perturbation in MR (4–7). However, the inverse problem, i.e., obtaining the source susceptibility distribution from magnetic field measurements, is more complicated. Provided that the shape/geometry of the susceptibility source is known, this problem can also be tackled as a forward problem approach by fitting the predicted field to the measured field (6, 7). Another way to solve this problem is by taking the direct inverse of the k-space kernel function. However, this inverse filter has a singularity at all points that satisfy the equation 1/3 = kz2/k2, and only regularization methods (8) or multiple acquisition methods (9) have heretofore been used to remove most of these artifacts.

In our approach, we have regularized the signal based on the proximity of the sampled point in k-space to the cone of singularity. The closer a k-space point is to the point of singularity, the more rapidly it is set to zero. This creates a smooth approach to zero from either side of the singularity where the function jumps rapidly from very small numbers to very large numbers. This appears to work fairly well in simulations giving systematic errors that depend on the object size. The signal-to-noise ratio in the final susceptibility maps appears to be reasonably well behaved with an error of 7.8% for 0.45 ppm (i.e., 0.035ppm) at 3T and TE = 5ms (assuming an initial 40:1 SNR in the magnitude images). As susceptibility increases, the effective SNR for the susceptibility map data will also increase. The SNR as a function of echo time is a bit more complicated. If there were no T2* effects and no phase aliasing, then the SNR would be expected to vary linearly with phase, i.e. increase with phase. However, since the signal decays according to exp(-TE/T2*), it is well known that this gives an optimal echo time of TE = T2*. Practically, images acquired at longer echo times (such as TE 25 ms at 3T, which is roughly the T2* value for normal venous blood) suffer from serious problems associated with signal loss and aliasing at the edge of the vein and also at air/tissue interfaces.

The ‘noise’ outside the brain in the SMs is significantly decreased with increasing threshold value, a. Table 3 presents mean and standard deviation of susceptibility values for three different sized veins with different threshold values. Quantitatively, the smaller the threshold value, the more accurate the susceptibility values. However, smaller threshold values also have more serious ‘noise’/artifacts (see Table-I). Therefore, when we choose a threshold value, we must compromise between the susceptibility values and artifacts/noise to get an acceptable susceptibility map. The threshold values between 0.05 to 0.2 seem to provide good choices depending on the application. If a more accurate estimate of oxygen saturation is needed, the lower value of 0.1 or 0.15 might be best, while, based on our experience, if it is overall CNR and the ability to evaluate the gray matter and white matter contrast in the susceptibility map, then 0.2 might be best.

Table 3.

Susceptibility values for different threshold values

| Vein\Threshold | a = 0.02 | a = 0.05 | a = 0.1 | a = 0.2 | a = 0.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 321 / 95 | 299 / 82 | 271 / 63 | 225 / 53 | 174 / 48 |

| V2 | 324 / 94 | 315 / 87 | 289 / 75 | 227 / 61 | 177 / 41 |

| V3 | 457 / 98 | 446 / 92 | 418 / 77 | 358 / 52 | 282 / 43 |

Mean and standard deviation of susceptibility values (in ppm × 1000) measured from the same three veins as in Table 2, obtained for different threshold values a = 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3. Phase data from TE=11.6 ms was used for susceptibility mapping. Increasing a values lead to more and more under estimation of the susceptibilities, in agreement with results in Table 1.

Effects of Echo Time on the Susceptibility Maps

A major feature of the susceptibility map is its theoretical independence of susceptibility to the choice of echo time. This is indicated in Figure 8 and Table 2. If the magnitude SNR and the phase information in the short echo time images were good enough, one would not need to use the long echo times that we do today for SWI for example. If a susceptibility map could be obtained from an echo time of 11ms and a repeat time of 15ms, it would be a much more efficient sequence and one which could also be used as an MRA sequence as well. Nevertheless, as also shown in Figure 8, there is indeed an susceptibility map-SNR (SM-SNR) dependence with echo time. We expect the SM-SNR to increase for TE approaching T2*. However, the effect of echo time is complicated since longer echo times will lead to aliasing around the vein. This aliasing coupled with partial volume effects creates a non-physical phase at the edge of the object. (By non-physical, we mean that there is no geometry or susceptibility distribution that can act as a physical source for this type of phase and therefore the inverse process will produce artifacts.) The expected dipolar phase without aliasing occurs outside this area and because of this the susceptibility map will have two parts to it. The first part is the correct reconstruction of a widened object based on the fact that the vessels exhibit the expected dipole behavior. The second part will be the systematic artifacts associated with aliasing and non-physical phase effects. These will lead to systematic noise and ghosting (or structural aliasing) associated with non-physical phases in the susceptibility maps. However, if the area in question has complete signal dephasing, setting the phase in this region to zero will give a magnetic moment close to the correct value in the widened object without much concern as to this non-perfect choice of central phase. In fact, that is why these images tend to reconstruct quite well despite all the potential problems. However, in closing this discussion, it should be realized that this is also the reason why we do not at this point try and use the quantified results of susceptibility maps to extract oxygen saturation. Finally, ghosting (or structural aliasing) remains even with no noise, creating a negative ring around the vessel. Larger objects suffer more from this error, and it is for this reason that objects larger than 16 pixels tend to have a nearly 10% systematic drop than the expected susceptibility.

Methods to Improve Quality of Susceptibility Map

Regularization is not the only means necessary to reconstruct good quality susceptibility maps. There are also key signal processing and image reconstruction concepts that need to be applied to the data to remove other types of artifacts. The first is a more finely sampled k-space. This avoids serious ghosting in the reconstructed susceptibility map. The second is spatial resolution high enough to allow for as many pixels as possible to give useful phase information outside the source. The third is echo time long enough for phase development so as to achieve sufficient phase SNR. The use of all these methods has led to the high quality images presented in this paper. In principle, one could actually collect higher resolution data in the read direction at the possible expense of signal-to-noise without an increase in acquisition time, while it would increase data acquisition time in either the phase or partition encoding direction. However, zero filling in the image domain to interpolate in k-space seems to suffice to remove much of the Gibbs ringing effects.

Moreover, reducing the presence of noise in the phase images is crucial in obtaining a high quality susceptibility map. Not only should the noisy pixels from the magnitude image be thresholded, but also areas of wildly varying phase coming from, for example, the skull where out-of-phase fat can cause a serious problem. Setting the phase inside spherical or cylindrical regions to be a constant also helps avoid phase noise effects. Areas of constant phase jumps will also generate a new type of structural ghosting artifact that we refer to as the inverse dipole rippling effect. That is, if the phase appears as a constant without the expected concomitant external phase behavior, then this rippling effect emanating from the source will permeate the image in a non-local fashion. A similar effect can be caused by remnant phases that survive the high pass filter. This leaves a non-physical phase at the edge of the brain. This could be tackled either by simply eliminating that tissue (and hence not obtaining useful susceptibility images in that part of the brain) or by using the forward model from the magnitude geometry constraints in an attempt to remove air/tissue interface phase effects (14). The better that this job is done, the less errors will permeate other parts of the brain from the rippling/ghosting effects described above.

Partial volume effects can cause a complete loss of phase information when the vein is much smaller than the slice thickness (13). For example, an aspect ratio of 1:4 appears to give the best cancellation effects and turns the phase inside small vessels from positive to negative for a right handed system. This leads to the issue of the reduced measured susceptibilities. There are a few causes for the reduced values: partial volume effects, phase aliasing and loss of signal due to spin dephasing around the magnetic source. In each of these cases, it is necessary to use the estimated size of the source larger than its actual value. For veins (cylinders), this means a reduction in the susceptibility by the ratio of the original area to the enlarged area, and for spheres a reduction in the susceptibility by the ratio of the original volume to the enlarged volume. Again, forcing the phase inside the object to be zero has little impact on the actual estimate for the magnetic moment (which is directly related to the product of the area times susceptibility for the veins or the volume times the susceptibility for a spherical microbleed for example). On the other hand, the partial volume effect can lead to smoothing effects. Although we do see the negative ring around the vessels in the in vivo data, the expected large dip in the center of the vessels is to a large degree absent.

The choice of how many slices to process to create a venous susceptibility map depends not so much on regional and global structural variations (as it does if one is estimating the effects of air/tissue interfaces (14)), but rather on how many slices the vessel phase appears in. This means that one can reconstruct the susceptibility map image with an arbitrary number of the acquired slices if one is interested only in local vessels and if this process removes more noise, it can lead to further improvement in the susceptibility maps.

Susceptibility mapping offers a means to study BOLD effects in an entirely different light. Although phase has been used in BOLD fMRI experiments, susceptibility values can be used to quantify changes in oxygenation levels and then infer changes in flow as well (15). In Figure 10, there is a clear increase in signal after ingestion of caffeine indicating an increase in deoxyhemoglobin levels. Measurements in other smaller veins together show an overall 30 to 40% increase in the susceptibility value after caffeine administration. This increase corresponds to a reduction in blood flow of close to 30% which is larger than what is usually observed for caffeine. This particular person was a non-coffee drinker and so the large amount of caffeine may have had an abnormally large effect. In this particular subject, no change in basal ganglia iron content was measured pre and post caffeine. Some small shifts in GM iron content could be found. These measurements may eventually help separate out the fractional contributions to phase from ferritin and deoxyhemoglobin.

In conclusion, we have shown that despite the problems in obtaining consistent susceptibility values for all vessels, it is possible to remove phase variations caused by major vessels in SWI high pass filtered phase images. This should be useful in creating SWI processed data without the associated non-local, long distance dipole effects. In the future, it may be possible to use this approach to evaluate quantitatively microbleeds and calcifications (16) and to map oxygen saturation from veins throughout the brain (rather than with the single vessel approach proposed initially in (17) and used more extensively in recent years (18, 19)). Finally, the images shown here present a new form of MR venography and can serve as a quantitative means to distinguish potential oxygen saturation abnormalities in SWI data. Future applications of susceptibility mapping may include iron measurements in tissue.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Award Number NHLBI R01HL062983-A4. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reichenbach JR, Venkatesan R, Schillinger DJ, Kido DK, Haacke EM. Small vessels in the human brain: MR venography with deoxyhemoglobin as an intrinsic contrast agent. Radiology. 1997;204:272–277. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng Y-CN, Reichenbach JR. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali Fatemi A, Boylan C, Noseworthy MD. Identification of breast calcification using magnetic resonance imaging. Med. Phys. 2009;36(12):5429–5436. doi: 10.1118/1.3250860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salomir R, Senneville BD, Moonen CT. A Fast Calculation Method for Magnetic Field In homogeneity due to an Arbitrary Distribution of Bulk Susceptibility. Concepts Magn Reson Part B (Magn Reson Engineering) 2003;198:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques JP, Bowtell R. Application of Fourier-Based Method for Rapid Calculation of Field Inhomogeneity Due to Spatial Variation of Magnetic Susceptibility. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance, Part B (Magn Reson Engineering) 2005;25:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch KM, Papademetris X, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Rapid calculations of susceptibility-induced magnetostatic field perturbations for in vivo magnetic resonance. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(24):6381–6402. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/24/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng YCN, Neelavalli J, Haacke EM. Limitations of calculating field distributions and magnetic susceptibilities in MRI using a Fourier based method. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2009;54:1169–1189. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/5/005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kressler B, de Rochefort L, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Jiang Q, Wang Y. Nonlinear Regularization for Per Voxel Estimation of Magnetic Susceptibility Distributions From MRI Field Maps. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2009 doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2023787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T, Spincemaille P, de Rochefort L, Kressler B, Wang Y. Calculation of susceptibility through multiple orientation sampling (COSMOS): a method for conditioning the inverse problem from measured magnetic field map to susceptibility source image in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Jan;61(1):196–204. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao B, Li T-Q, Gelderen Pv, Shmueli K, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Susceptibility contrast in high field MRI of human brain as a function of tissue iron content. Neuroimage. 2009;44(4):1259–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deville G, Bernier M, Delrieux J. NMR multiple echoes observed in solid 3He. Physical Review B. 1979;19:5666–5688. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandian DS, Ciulla C, Haacke EM, Jiang J, Ayaz M. Complex threshold method for identifying pixels that contain predominantly noise in magnetic resonance images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:727–735. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Haacke EM. The Role of Voxel Aspect Ratio in Determining Apparent Phase Behavior in Susceptibility Weighted Imaging. MRI. 2006;24:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neelavalli J, Cheng YCN, Jiang J, Haacke EM. Removing Background Phase Variations in Susceptibility Weighted Imaging Using a Fast, Forward-Field Calculation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:937–948. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, Kuppusamy K, Hoogenraad FGC, Takeichi H, Lin W. In Vivo Measurement of Blood Oxygen Saturation Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Direct Validation of the Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Concept in Functional Brain Imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1997;5:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z, Mittal S, Kish K, Yu Y, Hu J, Haacke EM. Identification of calcification with MRI using susceptibility-weighted imaging: A case study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;29(1):177–182. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haacke EM, Kuppusamy K, Thompson M, et al. High Resolution EPI fMRI using a head gradient coil insert. Proceeding of the fourth international conference on functional mapping of the human brain; Montreal, Canada. 1998. (Abstract 0547) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes S, Haacke EM. Susceptibility weighted imaging: clinical angiographic applications. MRI Clinical N Am. 2009;17:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langham MC, Magland JF, Epstein CL, Floyd TF, Wehrli FW. Accuracy and precision of MR blood oximetry based on the long paramagnetic cylinder approximation of large vessels. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:333–340. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]