Abstract

Objective

To assess parental health literacy and numeracy skills in understanding instructions for caring for young children, and to develop and validate a new parental health literacy scale, the Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT).

Methods

Caregivers of infants (age <13 months) were recruited in a cross-sectional study at pediatric clinics at three academic medical centers. Literacy and numeracy skills were assessed with previously validated instruments. Parental health literacy was assessed with the new 20-item PHLAT. Psychometric analyses were performed to assess item characteristics and to generate a shortened, 10-item version (PHLAT-10).

Results

182 caregivers were recruited. While 99% had adequate literacy skills, only 17% had >9th-grade numeracy skills. Mean score on the PHLAT was 68% (SD 18); for example, only 47% of caregivers could correctly describe how to mix infant formula from concentrate, and only 69% could interpret a digital thermometer to determine if an infant had a fever. Higher performance on the PHLAT was significantly correlated (p<0.001) with education, literacy skill, and numeracy level (r=0.29, 0.38, and 0.55 respectively). Caregivers with higher PHLAT scores were also more likely to interpret age recommendations for cold medications correctly (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.02, 2.6). Internal reliability on the PHLAT was good (KR-20=0.76). The PHLAT-10 also demonstrated good validity and reliability.

Conclusions

Many parents do not understand common health information required to care for their infants. The PHLAT, and PHLAT-10 have good reliability and validity and may be useful tools for identifying parents who need better communication of health-related instructions.

Keywords: Literacy, Parenting Skills, Infants, Safety

Introduction

In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) found that approximately 90 million Americans have basic or below basic literacy skills, and 110 million people have basic or below basic quantitative (numeracy) skills.1 Lower literacy and numeracy skills have been associated with poorer understanding of health information, poorer health behaviors, and worse clinical outcomes.2–14 For parents or caregivers, poor literacy and numeracy skills may create difficulties in understanding and applying health information to the care of their children. In order to care adequately for their children, parents must be able to comprehend common food and medication labels, medical provider recommendations, and health education materials. However, most written child health information is too complex for caregivers to comprehend and use appropriately.13–18 While the average adult reads at the 8th grade level, a large portion of parent education materials, including some materials produced by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), CDC (Vaccine Information Sheets), and state newborn screening programs remain above the 10th grade level.13–15,17,18 A few studies have shown that caregivers with lower literacy are less likely to understand important aspects of pediatric anticipatory guidance, including weighing risks and benefits of routine vaccinations, performing home safety checks, and handling common household emergencies.13,16,19 In general, lower caregiver health literacy is associated with worse family health behaviors and worse child health outcomes.10,20,21

Currently, there are no scales specifically designed for measuring the health literacy of parents of young children. Previous studies examining parent literacy have used scales that assess general literacy, or that primarily assess health literacy in the context of adult medical care. For example, the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults (S-TOFHLA), one of the most common measures of adult health literacy, includes a section that assesses an adult’s ability to read and understand how to prepare for a contrast radiograph of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Several recent studies have demonstrated that young adults tend to score very highly on the s-TOFHLA, even when they are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds that should correlate with low literacy.22–24 Recently, some of the developers of the s-TOFHLA have recognized this ceiling effect, and have suggested that the current scoring of the s-TOFHLA (to form the categories: “inadequate,” “marginal,” and “adequate”) are probably insufficient for many analyses.25,26 Given the potential limitations of current health literacy scales as well as the lack of one specific to the pediatric setting, we sought to develop a new health literacy scale specifically for parents, that focused on the ability of parents to understand and apply common child-health related information. The objectives of this study were (1) to assess parental health literacy and numeracy skills and (2) to develop and validate a new parent health literacy scale related to the care of young children, the Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT).

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed at pediatric clinics at three academic institutions to examine caregiver literacy and numeracy skills related to the understanding of common health tasks in caring for infants, and to validate the PHLAT. The Institutional Review Boards for all three institutions approved the study. All participants provided informed consent and were given a nominal reimbursement for their time.

Scale Development

The Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT) is a 20-item assessment scale designed to investigate the health literacy and numeracy skills of caregivers to infants (birth to 1 year of age). Items in the scale test common literacy- and numeracy-related tasks that parents perform when caring for young children -- including mixing infant formula, understanding breastfeeding recommendations, dosing over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medicines, and understanding nutrition labels.

For content validity, the scale was developed through an iterative process that included item generation from experts and parents, and cognitive interviewing to assess item comprehension. A group of experts in general pediatrics, pediatric health services research, pediatric pharmacy, pediatric psychology, public health, and health literacy were assemble to generate a list of initial possible scale items. Item content was derived from commonly available health information materials, including recommendations and parent-centered information from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Bright Futures (National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health).27 Question development was also guided by reviewing previously validated math and literacy tests (including the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults28, Diabetes Numeracy Test8,29, Wide Range Achievement Test30, Woodcock Johnson31, and Keymath32). In the initial development phase, 26 items were generated. This was then reduced to 25 items through an iterative process involving input from the expert group and parents of young children. In the second phase of development, these 25 items were administered to caregivers of infants (age < 13 months) who attended the pediatric clinics. Using cognitive interviewing, participants were asked questions about each scale item to assess the clarity and understandability of the scale items. If the item was unclear, the interviewee was encouraged to suggest an alternate format or wording. In response to the parent interviews and in an effort to eliminate item redundancy and emphasize the most important content areas, the expert panel reduced the scale to 20 items.

The 20 items on the PHLAT cover three clinical domains: nutrition/growth/development (9 questions), injury/safety (2 questions), and medical/preventive care (9 questions) (See Appendix). The PHLAT assesses a range of literacy and numeracy skills, including document literacy, addition, multiplication, division, fractions and percentages, multi-step mathematics, and numeration/number hierarchy. All of these domains and skills may be required of parents on a daily basis during their infant’s first year of life. There is no set time limit for completion of the PHLAT.

The third phase of development assessed the reliability and construct validity of the PHLAT. Reliability was evaluated through internal consistency testing with the Kuder-Richardson formula.33 There is no criterion (i.e. “gold standard”) validity for parental health literacy and numeracy. Therefore, an a priori model of correlations was determined by the expert panel to assess construct validity. We hypothesized that higher levels of education, income, literacy, and math skills would all be associated with improved PHLAT scores. We also hypothesized that a higher PHLAT score would be associated with a higher understanding of the age indications for pediatric over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications.

Study Setting and Participants

A convenience sample of participants was recruited from pediatric clinic sites at three academic medical institutions where faculty and residents care for a socioeconomically diverse range of patients. From September 2006 to October 2007, potential participants were approached in the clinic and asked to participate if they were the primary caregivers for infants (≤13 months) and were English speaking. Exclusion criteria included: corrected vision worse than 20/50 using a Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener or severe psychiatric illness.

Measures

Participants were given the following survey instruments: (1) a demographic questionnaire to assess basic patient characteristics, (2) a previously validated health literacy measure (Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, S-TOFHLA)28, (3) a validated measure of mathematics skills (Wide Range Achievement Test, third edition, WRAT-3),30 (4) the Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT), and (5) a survey to assess caregiver perception of the age indication of pediatric OTC cold medications.12 If a participant achieved a score of ≤22 on the S-TOFHLA (consistent with inadequate or marginal literacy), the research assistant read the demographic questionnaire aloud to the participant. (This occurred for two parents.) Other participants had the choice of completing the questionnaire on their own or participating verbally.

Trained research assistants administered all survey instruments in a private area in the clinic. Each research assistant was trained to be sensitive to the context of testing literacy instruments in a pediatric setting. Training included reflective discussions during survey pretesting, with a focus on remaining non-judgmental and encouraging each participant to try their hardest on each skills test. For some PHLAT items, participants were given a product, chart, or label corresponding to a specific test question. Participants were encouraged to examine the product, chart, or label fully before determining an answer. In addition, a separate survey was administered to gauge how caregivers understood and characterized the labeling on four OTC cold and cough medication products that were marketed for infant children at the time the study was performed. (Results of this survey were reported in a previously published manuscript.12) The products all recommended consulting a physician before using the medicine for children < 24 months of age. Participants were asked “Looking only at the front of this product, what age group is this medicine for?” Participants were then asked to view the entire label and were asked, “Would you give this product to a 13-month-old child with cold symptoms?”

Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics of all variables, including the individual items of the PHLAT, were calculated. Literacy, measured with the S-TOFHLA, was examined as a continuous variable (raw score) and a categorical variable (inadequate (≤16), marginal (≤22), or adequate (≥23)). Numeracy, measured with the WRAT-3, was also examined as a continuous variable (standard score) and a categorical variable (corresponding grade level).

Total PHLAT performance was calculated as the percent of questions answered correctly (score 0% to 100%). For construct validity, bivariate analyses examined the relationship between caregiver characteristics, literacy and numeracy level, and performance on the PHLAT.33 Correlations between performance on the PHLAT and continuous outcomes, including literacy (S-TOFHLA raw score) and numeracy (standardized WRAT-3 score) were performed using Spearman rank correlation coefficients. For categorical variables, average score on the PHLAT was compared using student t-tests or one-way analysis of variance.

Relationships between the PHLAT and patient understanding of the four OTC labels were examined using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with logit link to adjust for clustering at the caregiver level. Analyses examined the relationship between PHLAT score (dichotomized at the median to be High or Low) and each of the following: 1) caregiver response that products were appropriate for age < 24 months when looking at the front of the package, and 2) caregiver response that they would give the product to a 13-month-old with cold symptoms when looking at the entire package.

The Kuder-Richardson coefficient of reliability (KR-20), a variation of Chronbach’s alpha for dichotomous outcomes, was used to measure internal reliability of the PHLAT.33 Psychometric analyses were performed to examine the factor loading using principal factors analysis and principal component factors analysis. An abbreviated PHLAT scale (the PHLAT-10) was created by retaining items with the highest factor loadings and those questions deemed a priori to be of most clinical significance. The abbreviated scale was analyzed for internal reliability using the KR-20. Correlation between the PHLAT-10 and the PHLAT was assessed using Spearman rank correlation. Construct validity of the PHLAT -10 was examined by assessing the relationships between PHLAT-10 score and caregiver characteristics, literacy, and numeracy.

Results

From September 2006, through October 2007, 413 eligible caregivers were referred, 261 consented (63%), and 182 participated (70% of those consenting, and 44% of those initially referred). The primary reason for non-participation was lack of time (since recruitment occurred in a busy clinical setting. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants had similar characteristics to the families that seek care in our clinics, except that we excluded Spanish-speaking patients for purposes of this study. The majority of caregivers interviewed were mothers, and the youngest child in the family was an average of 4.5 months old (range 0–13 months). Most study participants had at least completed 12th grade or attained a GED. While only 1% of participants had inadequate or marginal literacy skills (as measured by the S-TOFHLA), 83% had lower than 9th grade math skills (as measured by the WRAT-3). Most participants reported that they had received health information about their new baby and had read books or magazines about parenting. Most participants also reported that they fed their infant either formula only or a combination of formula and breast milk. Over half of caregivers reported using OTC medications to treat a child’s fever, and 29% of caregivers had given OTC cold medications to children.

Table 1.

Caregiver Characteristics (N=182)

| Caregiver Characteristic | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Caregiver Age, yrs | 25.6 (6.1) |

| Female | 162 (89.0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 66 (36.5%) |

| Black | 93 (51.4%) |

| Hispanic | 19 (10.5%) |

| Other | 3 (1.7%) |

| Relationship to Child is Mother | 157 (86.7%) |

| Number of children in the family | 2.3 (1.5) |

| Age of youngest child, months | 4.5 (3.7) |

| Annual Family Income | |

| ≤ $19,999 | 78 (42.9%) |

| $20,000–39,999 | 62 (34.1%) |

| ≥ $40,000 | 19 (10.4%) |

| Do not know/Refused | 23 (12.5%) |

| Participates in WIC Program | 142 (78.0%) |

| Education | |

| < High school | 28 (15.5%) |

| High school or GED | 76 (42.0%) |

| Some college or above | 77 (42.5%) |

| Literacy status (STOFHLA) | |

| Inadequate | 1 (0.55%) |

| Marginal | 1 (0.55%) |

| Adequate | 180 (98.9%) |

| Numeracy skills (WRAT-3R). | |

| ≤ 5th grade | 64 (35.6%) |

| 6th-8th grade | 85 (47.2%) |

| High school or above | 31 (17.2%) |

| Since baby was born, received written info from a doctor or nurse about caring for new baby | 162 (89.0%) |

| Has read books about babies or parenting | 152 (84.0%) |

| Has read magazines about babies or parenting | 171 (94.0%) |

| Child receives | |

| Infant formula only | 115 (63.5%) |

| Breast milk only | 32 (17.7%) |

| Infant formula and breast milk | 34 (18.8%) |

| Uses OTC meds to treat fever in children | 94 (52.2%) |

| Uses OTC meds to treat a cold in children | 53 (29.1%) |

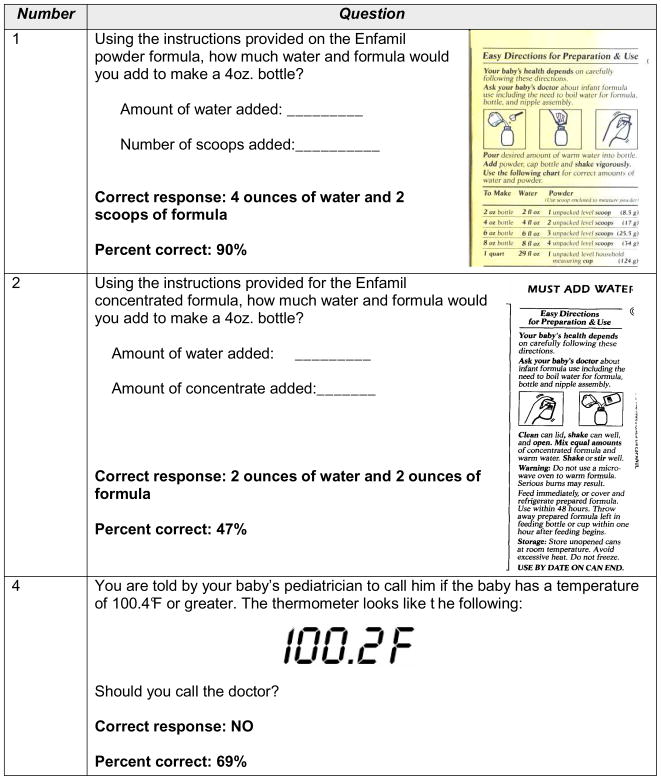

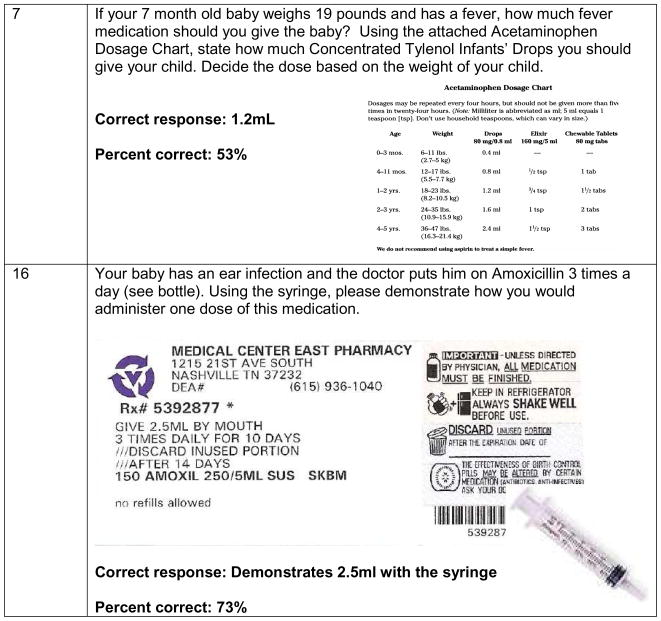

Overall, participants correctly answered 68% of the PHLAT questions (SD 18%, Range 10–100%). The average time to administer the PHLAT was 21 minutes (SD 6.9). Table 2 represents several sample questions and results on the PHLAT, and Table 3 demonstrates the range of topics covered. For example, only 73% were able to correctly dose a prescription for liquid amoxicillin medication using a syringe. Only 69% were able to correctly read a digital thermometer to determine if they should call their pediatrician for fever (after being given a specific temperature to use as a threshold for fever); only 53% were able to determine the proper dose using a liquid acetaminophen dosage chart. Only 64% could correctly determine if a juice had an adequate amount of Vitamin C to be eligible for the WIC program (after being instructed on what amount was sufficient). Only 51% could interpret a percentile on a growth curve. Very few (18%), after reading a brief breastfeeding guide, could determine how much time spent breast-feeding was less than normal.

Table 2.

Sample PHLAT Questions and Results

|

Table 3.

Sample PHLAT Topics and Results

| Number | Question Topic | % Correct |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Demonstrates how to make a 4 oz bottle of formula using powder based formula | 90% |

| 2 | Demonstrates how to make a 4 oz bottle of formula using concentrated formula. | 47% |

| 4 | Reads a digital thermometer to determine if a baby has a temperature of 100.4°F or greater. | 69% |

| 5 | Uses a car seat guidelines table to determine appropriate car seat and location for a 10 month old weighing 23 pounds. | 79% |

| 6 | Interprets a growth chart where the baby is at the 25th percentile for weight. | 51% |

| 7 | Interprets an Acetaminophen Dosage Chart, to determine how much medicine to give based on the weight of the child. | 53% |

| 10 | Refers to an Ibuprofen container and medicine cap to determine how many milliliters are in ½ teaspoon of medicine. | 60% |

| 16 | Reads a liquid antibiotic prescription and demonstrated with a syringe how to administer a dose of the medicine. | 73% |

| 17 | Calculates the number of 2 ounce servings of juice in a 32-ounce can of juice. | 73% |

| 18 | Interprets a food label to determine if it meets WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) Program guidelines of being 100% fruit or vegetable juice, and containing at least 30mg of Vitamin C per 100mL of juice, or 120% of the daily value of Vitamin C. | 64% |

| 20 | Reads and comprehends instructions regarding breastfeeding(Brochure from the Department of Health and Human Services) | 18% |

The framing of health information appeared to influence a caregiver’s ability to understand an item. For example (See Table 2), while 90% of caregivers could explain how to make a 4-ounce bottle using powdered formula (which included a table with mixing instructions), only 47% could correctly explain how to make a 4-ounce bottle using concentrated formula (which recommended to “mix equal amounts of formula and water”).

Correlations between caregiver characteristics and total PHLAT score are shown in Table 4. Higher performance on the PHLAT was significantly correlated (p<0.001 for all comparisons) with increased education (r=.29), literacy skill (r=0.38), and numeracy level (r=0.55). Participants who were African American or Hispanic, had lower income, or reported participation in the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program had significantly lower average PHLAT scores. Participants with less than 9th grade numeracy skills performed worse on the PHLAT than participants with higher numeracy skills (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Relationship of Caregiver Characteristics to PHLAT and PHLAT-10 Scores

| Caregiver Characteristic (n=182) | Mean PHLAT Score (SD) or Correlation (r) | p value | Mean PHLAT-10 Score (SD) or Correlation (r) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Age (yrs) | r=0.096 | 0.20 | r=0.078 | 0.30 |

| Age of Youngest Child (mos) | r=0.007 | 0.93 | r=0.06 | 0.40 |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 78 (13) | 78 (17) | ||

| Black | 63 (16) | 58 (22) | ||

| Hispanic | 58 (24) | 54 (28) | ||

| Annual Family Income | 0.0004 | 0.002 | ||

| ≤ $19,999 | 61 (19) | 58 (24) | ||

| $20,000–39,000 | 68 (16) | 67 (20) | ||

| ≥ $40,000 | 74 (16) | 72 (21) | ||

| Participation in WIC | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | ||

| No | 78 (14) | 77 (18) | ||

| Yes | 66 (18) | 62 (24) | ||

| Education | 0.0003 | 0.003 | ||

| < High school | 64 (18) | 61 (24) | ||

| High school or GED | 64 (19) | 60 (25) | ||

| Some college, or above | 74 (15) | 72 (20) | ||

| Education level, years | r=0.29 | 0.0001 | r=0.25 | 0.0007 |

| Literacy status(STOFHLA) | 0.10 | 0.12 | ||

| Inadequate/Marginal | 48 (4) | 40 (0) | ||

| Adequate | 69 (18) | 66 (23) | ||

| Raw STOFHLA Score | r=0.38 | <0.0001 | r=0.36 | <0.0001 |

| Numeracy Skills(WRAT-3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| < 6th grade | 58 (19) | 53 (23) | ||

| 6th-8th grade | 71 (14) | 68 (20) | ||

| High school and above | 83 (11) | 84 (15) | ||

| Standard WRAT Score | r=0.55 | <0.0001 | r=0.53 | <0.0001 |

| Total PHLAT Score | NA | NA | r=0.91 | <0.0001 |

Performance on the PHLAT was also significantly correlated with parental understanding of the age indications for use of child OTC cough and cold medications. When looking at the front of the label, caregivers with higher PHLAT scores were more likely to report correctly that an OTC cold medication was not appropriate for children < 24 months of age (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–4.0). When looking at the entire label, caregivers with higher PHLAT scores were more likely to report correctly that they would not give OTC cold medication to a 13-month-old child with cold symptoms unless they first consulted physician (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.02, 2.6).

Internal reliability of the PHLAT was good (KR-20=0.76). Psychometric analyses suggested that the PHLAT loaded to a single factor. Items with the highest loadings included items related to nutrition (e.g., formula mixing, breastfeeding instructions) and medication dosing. The shortened PHLAT, the PHLAT-10, retained seven items on nutrition, one item on understanding a growth chart, one item about medication dosing, and one item about amoxicillin dosing. The average score on the PHLAT-10 was 65% correct (SD 23, range 0–100). Correlation between the PHLAT-10 and the PHLAT was very high (r=0.91, p<0.0001). Correlation between the PHLAT-10 and other patient characteristics was very similar to the correlations between the PHLAT and other patient characteristics (See Table 4). Internal reliability of the PHLAT-10 was also good (KR-20 = 0.70).

Discussion

Of concern, this study found that many caregivers had difficulty understanding basic health information for the care of infant children. For example, 1 in 4 could not properly dose prescription medication or read a digital thermometer, one half could not properly dose over-the-counter medication or understand a growth chart, and more than 3 in 4 could not understand a commonly used breastfeeding brochure. The Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT) demonstrated excellent reliability and construct validity, suggesting that it may be a useful measure for assessing parental health literacy in the context of caring for young children. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate how literacy and numeracy correlate with basic understanding of health-based instructions related to infant care. It is also the first study to validate a specific parental health literacy and numeracy measure.

Psychometric analysis of the 20-item version of the PHLAT shows it has good reliability and validity in testing literacy and numeracy related skills of caregivers with young children. Higher PHLAT scores were significantly correlated with higher education level, literacy skill, and numeracy level. Compared with the Shortened Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adult (S-TOFHLA), the PHLAT seems to provide greater sensitivity as a measure of health literacy in the pediatric setting. While most caregivers had adequate literacy on the commonly used S-TOFHLA, they had a more diverse range in performance when tested with the PHLAT. This may be related to the ceiling effect on the S-TOFHLA, particularly among younger adults22–26, and/or because the PHLAT tests a more robust array of applied skills (both literacy and numeracy) more pertinent to the caregiver with infant children.34

The shortened 10-item version of the PHLAT, the PHLAT-10, also showed good reliability and construct validity. The PHLAT could be a useful tool for research purposes, while the PHLAT-10 may be a more useful tool in the clinical setting. We are currently testing the validity and reliability of both English- and Spanish-language versions of the PHLAT-10 in a larger study. In this new study we have adapted the PHLAT-10 to use pictures of labels rather than actual products to make the test more feasible to administer in a busy clinic setting. Future work should focus on validating a variation of the PHLAT for parents with older children, and on identifying meaningful approaches for interpretation and application of the PHLAT results in a clinical setting.

Results from the PHLAT highlight the many challenges that caregivers face in trying to provide daily appropriate health-related care for their infants. Caregivers were often unable to understand nutrition and medication labels, simple child-health handouts, and basic child-safety recommendations. Many were also unable to mix infant formulas or to dose liquid medication appropriately. The framing of health-related instructions, such as two different versions of how to mix infant formula, was associated with significantly different rates of parent understanding; suggesting both the effect of individual experience and the importance of clearly presenting health information.

Recent studies have shown associations between low maternal literacy and a decreased likelihood of breastfeeding, greater likelihood of smoking, and greater likelihood to have depressive symptoms.6,35–38 Also, children of caregivers with lower literacy skills have more unmet healthcare needs,39,40 more preventable use of the emergency room,5 and worse control of asthma and type 1 diabetes.5,41 Infants with parents of lower education or literacy also have worse health outcomes.20,21 In our current study, caregivers, particularly those with lower literacy and numeracy skills, consistently had problems making formula and understanding breastfeeding instructions, and interpreting nutrition labels. Lower PHLAT score was associated with a higher likelihood of caregivers inappropriately interpreting age indications of OTC cough and cold medications. OTC medication labels contain dense information that can be more challenging, and potentially misleading, for patients with lower health literacy and numeracy skills to understand.12 The correlation between the PHLAT and these common nutrition and medication activities may relate to clinically relevant outcomes, such as medication administration, although this requires further study.

This study has several limitations. This cross-sectional study only demonstrates associations and not causation. The utility of the PHLAT for longitudinal study needs to be demonstrated. We recruited a convenience sample of English-speaking caregivers from a population whose children were being seen at academic medical centers. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to all populations. Our literacy measure, the S-TOFHLA, had little variability among subjects and a ceiling effect, limiting the validation of our new measure against an assessment of caregiver health literacy. Additionally, we examined caregiver skills in a clinical setting, but these paper and pencil tests may not reflect actual behaviors at home. While we demonstrated the PHLAT was correlated with understanding of OTC labels, we did not specifically correlate performance on the PHLAT with any clinical outcomes, such as health status or receipt of preventative services. While we established the PHLAT had good construct validity, future prospective studies will need to demonstrate its predictive utility.

Our results have important implications for caregivers of young children, health care providers, industry, and federal agencies. All caregivers of young children –particularly the many caregivers with limited literacy and numeracy skills – face significant barriers to comprehending and implementing basic child-health tasks, such as providing appropriate nutrition, safety, and medication. Improving the clarity of child health information may be a critical factor for efforts that aim to improve the pediatric medical home – including preventive care, acute care, and care coordination for children. The Parental Health Literacy Activities Test may be useful to identify families who may benefit from verbal or pictorial instruction in the clinical setting. Our results suggest that pediatricians and health care providers may need to improve how they communicate with and educate caregivers of young children to perform many basic health-related skills. Health departments, pharmaceutical corporations, hospitals and academic medical centers can also use these results to inform future design improvements for the health system, including interactive health-education materials, user-friendly medication labels, and personal health records.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Matthew Oettinger and Steven Pattishall for their help with recruitment.

Funding: Dr. Rothman is currently supported by an NIDDK Career Development Award (NIDDK 5K23 DK065294). Dr. Perrin is currently supported by an NICHD career development award (NICHD K23 HD051817). Dr. Sanders’ work on this study was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Scholars Program. This research was also supported with funding from the NICHD (R01 HD059794) and the Vanderbilt Program on Effective Health Communication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No specific conflicts of interest exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulson C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES; 2008. p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Committee on Health Literacy. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and Health Outcomes. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeWalt DA, Dilling MH, Rosenthal MS, Pignone MP. Low parental literacy is associated with worse asthma care measures in children. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1278–1283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huizinga MM, Beech BM, Cavanaugh KL, Elasy TA, Rothman RL. Low numeracy skills are associated with higher BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1966–1968. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh K, Huizinga MM, Wallston KA, et al. Association of Numeracy and Diabetes Control. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient Understanding of Food Labels The Role of Literacy and Numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders LM, Federico S, Klass P, Abrams MA, Dreyer B. Literacy and Child Health: A Systematic Review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:131–140. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin HS, Dreyer BP, Foltin G, van Schaick L, Mendelsohn AL. Association of low caregiver health literacy with reported use of nonstandardized dosing instruments and lack of knowledge of weight-based dosing. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lokker N, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental misinterpretations of over-the-counter pediatric cough and cold medication labels. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1464–1471. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Wills G, Miller S, Abdehou DM. The gap between patient reading comprehension and the readability of patient education materials. J Fam Pract. 1990;31:533–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, Fredrickson D, Bocchini JA, Jr, Jackson RH, Murphy PW. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93:460–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold CL, Davis TC, Frempong JO, et al. Assessment of newborn screening parent education materials. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S320–S325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2633L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Jr, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Alessandro DM, Kingsley P, Johnson-West J. The readability of pediatric patient education materials on the World Wide Web. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:807–812. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis TC, Humiston SG, Arnold CL, et al. Recommendations for effective newborn screening communication: results of focus groups with parents, providers, and experts. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S326–S340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2633M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llewellyn G, McConnell D, Honey A, Mayes R, Russo D. Promoting health and home safety for children of parents with intellectual disability: a randomized controlled trial. Res Dev Disabil. 2003;24:405–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armar-Klemesu M, Ruel MT, Maxwell DG, Levin CE, Morris SS. Poor maternal schooling is the main constraint to good child care practices in Accra. J Nutr. 2000;130:1597–1607. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.6.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levandowski BA, Sharma P, Lane SD, et al. Parental literacy and infant health: an evidence-based healthy start intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:95–102. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janisse HC, Naar-King S, Ellis D. Brief Report: Parent’s Health Literacy among High-Risk Adolescents with Insulin Dependent Diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oettinger MD, Finkle JP, Esserman D, et al. Color-coding improves parental understanding of body mass index charting. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran TP, Robinson LM, Keebler JR, Walker RA, Wadman MC. Health Literacy among Parents of Pediatric Patients. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:130–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC, et al. Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson J, Baker DW. In search of ‘low health literacy’: Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, et al. Development and validation of the Diabetes Numeracy Test (DNT) BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson GS. WRAT3: Wide Range Acheivement Test Administration Manual. Wide Range Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock Johnson Tests of Acheivement. 3. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connolly AJ, Natchman W, Pritchett EM. Key Maths,Diagnostic Arithmetic Test. American Guidance Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman H, Skipper B, Small L, Terry T, McGrew M. Effect of literacy on breast-feeding outcomes. South Med J. 2001;94:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fredrickson DD, Washington RL, Pham N, Jackson T, Wiltshire J, Jecha LD. Reading grade levels and health behaviors of parents at child clinics. Kans Med. 1995;96:127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett I, Switzer J, Aguirre A, Evans K, Barg F. ‘Breaking it down’: patient-clinician communication and prenatal care among African American women of low and higher literacy. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:334–340. doi: 10.1370/afm.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poresky RH, Daniels AM. Two-year comparison of income, education, and depression among parents participating in regular Head Start or supplementary Family Service Center Services. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:787–796. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broder HL, Russell S, Catapano P, Reisine S. Perceived barriers and facilitators to dental treatment among female caregivers of children with and without HIV and their health care providers. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders LM, Lewis J, Brosco JP. Low Caregiver Health Literacy: Risk Factor for Child Access to a Medical Home. Pediatric Academic Societies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross LA, Frier BM, Kelnar CJ, Deary IJ. Child and parental mental ability and glycaemic control in children with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2001;18:364–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]