Abstract

There is clear evidence for intraluteal production of prostaglandins (PGs) in numerous species and under a variety of experimental conditions. In general, secretion of PGs appears to be elevated in the early corpus luteum (CL) and during the period of luteolysis. Regulation of intraluteal PG production is regulated by a variety of factors. An autoamplification pathway in which PGF-2alpha stimulates intraluteal production of PGF-2alpha has been identified in a number of species. The mechanisms underlying this autoamplification pathway appear to differ by species with expression of Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) and activity of phospholipase A2 acting as important physiological control points. In addition, a number of other responses that are induced by PGF-2alpha (decreased luteal progesterone, increased endothelin-1, increased cytokines) also have been found to increase intraluteal PGF-2alpha production. Thus, regulation of intraluteal PG production may serve to initiate or amplify physiological signals to the CL and may be important in specific aspects of luteal physiology particularly during luteal regression.

Introduction

Although progesterone is the major luteal hormone, the CL also produces a number of other substances including prostaglandins (PGs) and oxytocin. The PGs are of particular interest because of their potential autocrine/paracrine actions within the CL. The involvement of PGF2α in regression of the CL in many species makes it likely that there is a role for intraluteal PGF2α production in luteal regression. In addition, functional roles for PGs in the early CL have also been postulated [1,2]. In this review the general pathways in PG production will be reviewed (Section I) before discussion of the evidence for and the timing of intraluteal PG production in various species (Section II). Although many factors can regulate intraluteal PG production, amplification pathways within the CL that are induced by PGF2α (Section III) or other factors (Section IV) will be emphasized in this review. Some speculations on the physiological role of intraluteal PG production are also provided (Section V). Other excellent reviews have been previously published on regulation of intraluteal PG production [1,2] that contain material not discussed in this review.

General Pathways for Production of Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are derivatives of membrane phospholipids that regulate diverse physiological processes such as pregnancy, ovulation, luteolysis, inflammation, gastric secretion, and blood flow. The substrates for PG synthesis are arachidonylated phospholipids, such as plasmenylcholine, phosphatidylcholine, and alkylacyl glycerophosphorylcholine. Prostaglandin biosynthesis begins with the liberation of arachidonic acid from these membrane phospholipids. This step is primarily catalyzed by the hormone-responsive enzyme cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) [3]. The cPLA2 is one member of a larger family of enzymes organized into 11 groups (I-XI) that also include various secreted forms of PLA2 [4]. An increase in free intracellular calcium can cause activation of cPLA2 by binding to an amino-terminal domain causing translocation to cellular membranes, particularly to the nuclear envelope and endoplasmic reticulum, where it can hydrolyze arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids (see review by Gijon and Leslie [5]). However, one study did not detect translocation of cPLA2, but found that active or inactive cPLA2 was randomly distributed in the cytoplasm [6]. Phosphorylation by MAP kinases of Ser 505 [7] can also contribute to full activation of cPLA2. In some cell types, activation of PKC and/or inhibition of certain phosphatases with okadaic acid also contribute to cPLA2 activation [5]. Recent findings indicate that there is sustained cPLA2 activity during luteolysis in the pseudopregnant rat [8].

Free arachidonic acid is converted to PGH2 by the enzyme cyclooxygenase (Cox). This is generally considered the rate-limiting step in PG production and commits arachidonic acid to the PG synthesis pathway. There are two enzymatic steps in the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGH2. First, a cyclooxygenase step that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGG2 and a second peroxidase step that reduces PGG2 to PGH2. At least two isoforms of Cox exist, Cox-1 and Cox-2 that catalyze conversion of arachidonic acid to PGH2 through a similar catalytic site and mechanism. A third Cox isoform, Cox-3, was postulated [9] and has been recently isolated and characterized [10]. This enzyme is derived from the Cox-1 gene but with retention of intron 1 in the mRNA. The physiological function of this third isoform or other Cox isoforms has not yet been determined, but Cox-3 may be the elusive target for acetaminophen action [10]. Cox-1 is characterized by constitutive expression in many tissues and may regulate various homeostatic functions such as arterial blood pressure [11] and gastric epithelium function [12]. Cox-2 is inducible in many tissues and has been found to regulate PG production during many acute responses such as inflammation [13]. Many non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and indomethacin inhibit both Cox-1 and Cox-2; there are now Cox-2 specific inhibitors available commercially and for research purposes. Regulation of Cox-2 expression has been clearly demonstrated in the CL, as discussed below.

There is no clear evidence that we are aware of that arachidonic acid requires specific transport proteins to reach the Cox enzymes; however, there appears to be utilization of different arachidonic acid pools by Cox-1 and Cox-2 within the same cell. Antisense Cox-2 RNA treatment of murine macrophages blocks endotoxin-induced PGE2 production, but not arachidonic acid release. The constitutively present Cox-1 enzyme in these cells was unable to use this pool of endotoxin-stimulated arachidonic acid [14]. Surprisingly, addition of exogenous arachidonic acid to the media could be utilized by Cox-1, but not by Cox-2. In mouse mast cells, cytokine treatment (IL-10 + IL-1β + Kit ligand) induces Cox-2 and PGD2production, while IgE plus hapten-specific antigen induces Cox-1-mediated PGD2 production that is not affected by the presence of Cox-2 [15]. These results in macrophages and mast cells indicate that Cox-1 and Cox-2 utilize different pools of arachidonic acid. The subcellular localization of Cox-1 and Cox-2 differ and this may be important for the differential use of substrate by these enzymes. Intense Cox-2 immunostaining is observed on the nuclear membrane, while Cox-1 immunostaining is equally localized to the ER and nuclear membrane [16]. Using a histoflouresense method for determining Cox activity, Morita et al. [16] found Cox-1 activity associated mainly with the ER, while Cox-2 activity was mostly in the nucleus. Intriguingly, as mentioned above, activated cPLA2 also localizes to perinuclear membranes. Thus, activated cPLA2 and Cox-2 may be in close subcellular proximity and this may explain why cPLA2-released arachidonic acid is utilized by Cox-2 while exogenously-added arachidonic acid is utilized by Cox-1 (reviewed in [5]). Subcellular distributions and differential utilization of arachidonic acid has not yet been experimentally evaluated in the CL.

After conversion of arachidonic acid to PGH2 there can be production of a wide variety of PGs according to the particular PG synthase enzymes that are present. The PGF-synthase enzyme has been cloned and is a member of the aldo-keto reductase family of enzymes that includes 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [17]. PGF-synthase mRNA has been identified in the CL but PGF2α treatment did not alter steady-state PGF-synthase mRNA concentrations [18]. Many cells, including luteal cells, have been found to produce multiple PGs that may have differential actions [19]. In luteal cells from day 17 pseudopregnant pigs, there is induction of luteal production of both PGF2α and PGE2 by treatment with PGF2α [20]. This is surprising because PGF2α is considered to be luteolytic while PGE2 is considered to be luteotropic. Thus, although differential expression of PG synthase enzymes seems like a potential mechanism to direct production of specific PGs, we have not yet found evidence of this differential regulation in the luteal cell literature.

Intraluteal metabolism of PGF2α could also be a physiologically regulated event. It has been known for many years that there is an enzymatic activity termed PGE2-9-ketoreductase that can convert PGF2α to PGE2 or alternatively PGE2 to PGF2α [21]. Similar to PGF-synthase, this enzyme was found to be part of the aldo-keto reductase family of enzymes [22]. Surprisingly, a pure preparation of the 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme was found to also contain PGE2-9-ketoreductase activity [22]. Similarly, the sequences of the mRNA for these 2 enzymes are identical [23] suggesting that the enzyme that inactivates progesterone may also inter-convert PGs within the CL. Nevertheless, a functional role for PG conversion activity by this enzyme in the CL has not been determined. PGF2α can also be metabolized to the inactive PG, 13,14-Dihydro-15-Keto-PGF2α (PGFM) by the enzyme 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (PGDH) [24]. Local metabolism of PGs has been reported in many tissues including the CL [25]. We found that PGDH mRNA was abundant in the pig CL [20]. In the sheep CL, PGDH activity is greatest in the early CL and during maternal recognition of pregnancy, both times when the CL is relatively resistant to PGF2α action [25]. This suggests that PGDH expression may have a luteoprotective role in the CL by inactivating any PGF2α that is produced; however, this hypothesis will require further experimental evaluation.

Prostaglandins have both hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains that should make it difficult for these compounds to traverse cellular membranes. Indeed, cellular transporters of PGs have been identified. These PG transporters contain 12 transmembrane domains and are part of the organic anion transport class of transmembrane proteins [26]. Expression of these transporters in Xenopus oocytes or HeLa cells allows entry of PGs into these cells [26]. Cell that synthesize PGs (as determined by Cox expression) also have substantial expression of the PG transporter [27] and this may be important for release of the synthesized PGs. Similarly, it seems likely that expression of PG transporters may be required to allow secretion of PGs from luteal cells; although this idea has never been tested.

Intraluteal actions of PGs are likely to be mediated through the plasma membrane PG receptors that are pharmacologically designated by their major PG ligand. For example, the receptors that bind PGF2α with high affinity have been designated FP receptors; whereas, the receptors that bind PGEs with high affinity are designated as EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4. The FP receptor mRNA is induced in bovine granulosa cells within 1 d after the LH surge and is expressed at more than 100-fold greater concentration in the CL than in any other tissue [28]. Binding to the plasma membrane FP receptor probably requires an extracellular location for PGF2α to cause activation. There also appears to be expression of EP3 receptor in the CL; however, it is present at much lower concentrations than luteal FP receptor [28]. Conversely, intracellular PGs could potentially interact with specific peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs). The PPARs act as transcriptional factors and PPARγ has been found to be activated by PGJ2, a metabolite of PGD2 [29]. It seems likely that regulation of the transport of PGs through the plasma membrane (extracellular vs. intracellular) could be a mechanism for regulation of functional effects by luteal cell-derived PGs. This manuscript will primarily discuss the luteal production of PGs; however, a complete understanding of luteal PG action must also consider the diversity of distinct PG receptors linked to varying intracellular effector systems within the CL.

Changes in Intraluteal PG Production During the Luteal Phase

As mentioned above, the corpora lutea of various species have the capacity to synthesize PGs (rats [19], rabbits [30], pigs [31-34], sheep [18,35], cows [36,37], horses [38], rhesus monkeys [39], cynomolgus monkeys [40], women [41]). Investigators have assessed the pattern of change in luteal PG production throughout the luteal phase in a number of different species. The objective of these experiments was frequently to determine if changes in luteotropic or luteolytic PGs coincided with developmental or regressive changes in luteal function. Often this was done by surgically removing the corpora lutea at three to four different stages of the cycle or pseudopregnancy. These stages represented luteal developmental (early luteal phase), maximal function (mid-luteal phase), and luteal regression (late luteal phase). Dispersed cells or tissue samples were incubated to assess their capacity to produce the various prostaglandins. Luteotropic PGs examined were PGE2 and PGI2 (as reflected by its major metabolite 6-keto-PGF1α). The luteolytic PG examined was PGF2α. Below we will discuss some experiments of this nature in various species.

Rats

Prior to examining luteal production of PGs in rats, studies were designed to examine how luteal concentrations of PGs varied throughout pseudopregnancy. Luteal concentrations of PGF2α increased as the luteal phase progressed from day 7 to 13 of pseudopregnancy in rats [42]. Luteal concentrations of PGE were greatest on day 11 and decreased by day 13. Luteal production of PGF2α and PGE2 increased from day 7 to 10 and declined to day 13 of pseudopregnancy [19]. These increases in PG production coincided with the onset of decreased luteal progesterone production as the CL transitioned from day 7 to 10. Luteal production of 6-keto-PGF1α did not change over time.

Pigs

Porcine luteal tissue was collected from the slaughterhouse and staged on the basis of morphological and histological criteria. Corpora lutea were assigned to the following groups: early luteal (day 3–6), mid-luteal (day 7–14), and late-luteal (including corpora albicantes, day 15–19) [33]. Production of PGF2α and PGE2 decreased from the early to the mid-luteal phase and rebounded in the late luteal phase. The rise in PGF production from the mid to late luteal phase supports an earlier study from the same authors [34]. Using pigs whose stage of the estrous cycle was carefully monitored, Guthrie and Rexroad studied changes in luteal prostaglandin production in CL collected on day 8, 12, 14, 16, and 18. They also observed an increase in PGF2α production as the corpus luteum transitioned from mid to late luteal phase [31].

Cows

Early bovine CL produced the highest levels of PGI2 (as reflected by its major metabolite 6-keto-PGF1α) and PGF2α compared to mid- and late cycle [36]. Similar results were observed by Rodgers et al. [43]. These patterns of change in luteal production over time were reflected in the initial prostaglandin content. The ratio of the initial content of PGF2α:6-keto-PGF1α increased as the cycle progressed [36]. Koybayashi et al. [44] used an intraluteal microdialysis system to study production of luteal prostaglandins in vivo during days 3–6 of the estrous cycle. They found that luteal secretion of PGF2α and PGE2 was elevated on day 3 and was relatively diminished on days 4–6. Consistent with these results on PG secretion, they also found that luteal concentrations of Cox-2 mRNA were greater in the early than in the mid to late luteal phase. In an experiment by Grazul et al. [45], patterns of luteal production of PGF2α did not vary significantly by stage of cycle. DelVecchio et al. [46-48] compared luteal production of prostaglandins collected at two stages of the estrous cycle. They found that luteal cells derived from late bovine CL produced more PGE2 and PGF2α than those derived from mid-cycle CL.

Horses

Corpora lutea were collected from mares on days 4–5, 8–9, and 12–13 [38]. Production of PGF, PGE2, and 6-keto-PGF1α was highest in corpora lutea collected in the early luteal phase. PGE2 production increased from CL collected on days 8–9 to days 12–13, but production of the other prostaglandins did not change over this interval. The ratio of PGF:PGE2 increased from days 4–5 to days 8–9, and remained higher than early in the luteal phase on days 12–13.

Non-human old world primates

In the rhesus monkey [49], luteal production of PGE2 and 6-keto-PGF1α, was highest in the early luteal phase, decreased in mid-luteal phase, and remained suppressed in late luteal phase. The notion of a luteotropic role for PGE2 and PGI2 in primate CL was supported by significant positive correlations between luteal production of P and that of PGE2 and 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of PGI2). Concentrations of PGF2α decreased from early luteal phase to mid-luteal phase, but in contrast to the luteotropic PGs, rebounded in late luteal phase to levels observed in early luteal phase. No differences were observed in the ratio of PGE2/PGF2α during the luteal phase, but there was a tendency for an increase in the ratio of PGF2α :6-keto-PGF1α from early luteal phase to mid-luteal phase, similar to the results from studies in cattle [36].

In the cynomolgus monkey, luteal production of PGF2α was highest in the early luteal phase, and there was no apparent rebound in the late luteal phase as was observed in the rhesus monkey [40]. Luteal production of PGE2 was high in the early luteal phase, decreased in the mid-luteal phase, and rebounded in late luteal phase to levels observed in early luteal phase.

Humans

Prior to studying luteal PG production, the content of PGs in the human CL was considered. In two experiments [50,51] there was a significant increase in luteal PGF2α concentration as the CL progressed from the mid to late luteal phase. Swanston et al. [52] also observed an increase in luteal content of PGF2α, but this increase occurred as late CL became corpora albicantes. Patwardhan and Lanthier [41] observed an increase in PGF content as the CL progressed from early to mid-luteal phase, and the high level was maintained during the late luteal phase.

Recently, PG production by human CL of different stages was assessed [53]. In this study, only two stages were considered, mid-luteal phase (days 5–9 after ovulation) and late luteal phase (days 10–14 after ovulation). Luteal production of PGF2α, PGE2, and 6-keto-PGF1α were significantly higher in the mid vs. late luteal phase.

To evaluate relative changes in PG synthetic enzymes over time, human CL were studied using immunocytochemistry [54]. Cyclooxygenase and PGF2α synthase were reported to qualitatively increase from early to mid-luteal phase and to further intensify by late luteal phase. Prostaglandin I2 synthase appeared to be most prevalent in mid-luteal phase CL when compared to the other two stages examined. These data are consistent with the notion that luteal production of luteolytic PG increases as the luteal phase progresses in the woman. The data support the studies mentioned above with respect to luteal content of PGF2α [41,50-52], but they are not consistent with the PG production data of Friden et al. [53].

In assessing these types of studies, it can be seen that differences exist in the patterns of luteal PG production across species and experiments. However, with some exceptions, there are similarities that can be noted. First of all, luteal production of luteolytic and luteotropic PGs is often high in the early luteal phase. Many have suggested that the luteotropic PGs may play a role in luteal development, and it is well known that young corpora lutea are not sensitive to the luteolytic effects of PGF2α. Additionally, in many studies/species there is either an increase in production of PGF2α as the CL ages from mid- to late luteal phase, or there is an increase in the ratio of PGF2α :PGE2 or PGF2α :6-keto-PGF1α. As such, the balance of luteolysin to luteotropin often favors the luteolysin in the late luteal phase. Thus, a combination of changes in luteal production of luteotropic and luteolytic PGs and changes in the responsiveness of luteal tissue to these PGs may play a role in controlling luteal function in various species.

Regulation of Intraluteal PG by PGF2α

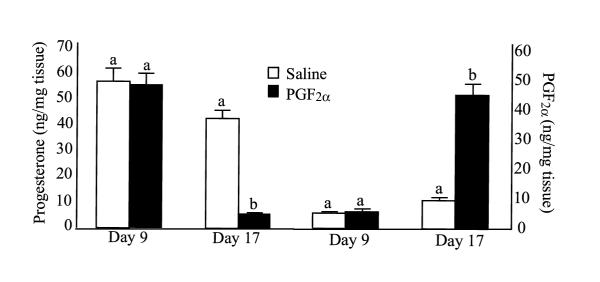

One of the most intriguing aspects of luteal PGF2α production is that there appears to be an autoamplification loop such that treatment of luteal cells with PGF2α induces production of PGF2α by luteal cells. In initial reports of this phenomenon, researchers treated sheep [35] or pigs [55] with cloprostenol (PGF2α analog) in vivo, removed the corpora lutea, and then incubated luteal slices in vitro. In these studies treatment in vivo with a PGF2α analog dramatically increased the in vitro production of PGF2α. Similarly, treatment of large luteal cells in vitro with PGF2α or activation of PGF2α second messenger pathways (free calcium, activation of PKC) can increase PGF2α production in vitro [18,20]. As shown in Figure 1, this increase in PGF2α production only occurs in CL with luteolytic capacity (from pigs on day 17 of pseudopregnancy) and not in CL without luteolytic capacity (day 9 of the estrous cycle) [20]. Thus, there is clear evidence for an intraluteal positive feedback pathway for PGF2α production and this pathway appears to be associated only with CL that undergo regression after a single treatment with PGF2α.

Figure 1.

Secretion of (A) progesterone and (B) PGF2α from tissues from gilts on day 9 of the estrous cycle or day 17 of pseudopregnancy treated in vivo with a PGF2α analog (Cloprostenol) 10 hours prior to ovary removal. Progesterone and PGF2α were measured in media following 2 hour incubation of collected porcine luteal tissue. A, B – statistically different (P < 0.05) within day (from [20]).

There are probably multiple intracellular mechanisms involved with PGF2α-induced production of intraluteal PGF2α. There is evidence that PLA2 activity is increased during luteolysis [56]. Treatment with PGF2α dramatically increases free intracellular calcium in large luteal cells [57] and free calcium will bind to cPLA2 causing translocation to the nuclear membranes. In addition, PGF2α treatment activates MAP kinases [58] and activates PKC [59], both intracellular effectors that can contribute to activation of cPLA2. There was no detectable increase in luteal cPLA2 mRNA after in vivo treatment with PGF2α [60], suggesting that luteal changes in cPLA2 were probably mediated by protein activation rather than transcriptional regulation. Thus, treatment of CL with PGF2α is likely to cause translocation and activation of cPLA2 through a number of key intracellular pathways allowing liberation of free arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids. Treatment in vivo with PGF2α also dramatically increases expression of Cox-2 mRNA and protein [18,20,61]. In vitro treatment of large luteal cells with PGF2α or activators of intracellular effector systems that are activated by PGF2α also dramatically increased Cox-2 mRNA, protein, and PGF2α production [18,20]. Thus, PGF2α will activate both of the key rate-limiting steps in PGF2α production by activating the cPLA2 protein and by inducing Cox-2 activity.

The molecular mechanisms involved in PGF2α induction of Cox-2 have been analyzed. There was about a 40-fold induction of reporter gene expression following treatment of transfected large luteal cells with PGF2α [62]. This induction could be inhibited by a specific inhibitor of PKC, myristolated pseudosubstrate for PKCα and β. Inhibitors of calcium calmodulin kinase and the MAP kinase pathways had no effect on PGF2α induction of Cox-2. We have found that there are three key DNA response elements in the 5' flanking DNA region that act synergistically to regulate induction of Cox-2 by PGF2α in ovine large luteal cells [62]. The most critical element is an E-box region that is about 50 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site. Thus, PGF2α, acting through PKC and an E-box DNA element, specifically increases Cox-2 gene transcription.

The mechanisms underlying the stage-specific regulation of this autoamplification pathway remain unresolved in spite of recent studies using a variety of luteal models. In the bovine CL, PGF2α induces expression of Cox-2 mRNA only in CL with luteolytic capacity (day 11 of estrous cycle). In the bovine CL without luteolytic capacity (day 4), treatment with PGF2α induces a number of cellular responses, indicating that the PGF2α does activate FP receptors in the early CL, but there is no induction of Cox-2 mRNA [61,63]. In non-luteinized granulosa cells, activation of protein kinase (PK) A by cAMP was a potent stimulator of Cox-2 gene expression; whereas, PGF2α had no effect on Cox-2 expression. However, after 7 days of luteinization during culture, PGF2α became a potent stimulator of Cox-2 expression, similar to the timing observed in vivo [64]. In ovine granulosa cells, Cox-2 mRNA and PGF2α secretion were also induced by activation of the PKA but not the PKC pathway [62]. In contrast in ovine large luteal cells, Cox-2 mRNA and PGF2α production were primarily stimulated by PKC and not PKA. Wu and Wiltbank used bovine granulosa cells to evaluate the changes in expression of the Cox-2 promoter linked to a luciferase reporter during luteinization and acquisition of luteolytic capacity [65]. In non-luteinized granulosa cells, activation of PKA but not PKC dramatically increased Cox-2 promoter-driven expression. However, after 8 days of luteinization the promoter became responsive to PKC and PGF2α but not to PKA activation. Intriguingly, the induction of the Cox-2 promoter by either PKA (non-luteinized granulosa cells) or PKC (luteinized granulosa cells) was mediated by the E-box element mentioned above. Tsai et al., also found that human granulosa-lutein cells, only display this PGF2α autoamplification pathway after 8 days of luteinization [66]. In early granulosa-lutein cells (day 2 of culture) there is no increase in Cox-2 in response to PGF2α treatment. However after 8 days of luteinization, PGF2α dramatically induced Cox-2 mRNA and inhibited progesterone production, indicating the acquisition of luteolytic capacity develops over time in culture.

In contrast to the studies cited above using bovine, ovine, and human luteal or granulosa-lutein cells, studies with the pig CL have not found an association between luteal Cox-2 expression, luteal PGF2α production, and luteolytic capacity [20]. In vivo treatment with PGF2α induced expression of Cox-2 mRNA and protein in either CL without luteolytic capacity (day 9) or with luteolytic capacity (day 17). However, there was no increase in luteal PGF2α production in day 9 CL (Figure 1) in spite of the dramatic induction of Cox-2 mRNA. We were unable to determine the rate-limiting step that prevented induction by PGF2α of intraluteal PGF2α production in the early pig CL [20].

The physiological significance of this autoamplification pathway has not yet been clearly defined but it would allow small amounts of PGF2α from the uterus to induce a dramatic increase in intraluteal PGF2α production. Intraluteal PGF2α production may be crucial for complete luteolysis. In an elegant series of recent experiments, Griffeth et al. [67], found that intraluteal treatment with the PG synthesis inhibitor, indomethacin, prevented the decrease in luteal weight that is normally associated with luteal regression; although, the decrease in luteal progesterone production was not affected. Intriguingly, they also reported that in hysterectomized ewes, doses of PGF2α (1 mg and 3 mg) that caused luteal regression also induced peaks of PGFM at 12–36 hours after PGF2α treatment. These peaks of PGFM were not of uterine origin and may have originated from the CL.

Other Regulators of Intraluteal PG Production

It appears that secretion of PGF2α and progesterone are interrelated. Treatment of CL that have luteolytic capacity with exogenous PGF2α inhibits progesterone production. Conversely, treatment of bovine luteal cells with progesterone decreased PGF2α production in a dose-dependent fashion [68]. However, progesterone may affect intraluteal PG production differently in CL with or without luteolytic capacity. Okuda and Skarzynski [1] reported that blockade of the progesterone receptor with a highly selective progesterone antagonist, onapristone, inhibited PGF2α production by bovine luteal cells from the early CL (Days 4–5); whereas, onapristone treatment increased PGF2α production by bovine luteal cells from mid-cycle CL (Days 8–12). Thus, the effect of progesterone in regulating intraluteal PG production may shift from stimulatory to inhibitory during luteal development.

Cytokines are also potent stimulators of luteal PGF2α production. Interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α dramatically stimulated PGF2α production by cultured bovine luteal cells [37,69,70]. The acute stimulation of PGF2α production has been postulated to occur through activation of cPLA2 [70-72]. The chronic effects (72 h) of interleukin-1β may be mediated by upregulation of Cox [70]. In human luteinized granulosa cells, interleukin-1β was also found to increase prostanoid synthesis, increase Cox-2 mRNA, and decrease Cox-2 mRNA degradation [73]. Interferon-γ has also been found to stimulate luteal PGF2α production, but only after 72 h of treatment [74]. Of particular importance, all of the stimulatory effects of these three cytokines on PGF2α production could be inhibited by simultaneous treatment with progesterone [37,71,74]. Although cytokines increase PGF2α production, it does not appear that PGF2α production is required for cytokine-mediated inhibition of progesterone production or induction of cell death because indomethacin treatment did not prevent these cytokine actions [74,75].

Another peptide that appears to be critical in luteolysis is endothelin-1 (ET-1; see Milvae [76] for review). Treatment with ET-1 decreases progesterone production from bovine luteal cells in vitro or in vivo, an effect blocked by a specific ETA receptor antagonist [77,78]. In bovine microdialized CL, ET-1 was effective at decreasing progesterone only after CL were exposed to PGF2α [79]. Moreover, there appears to exist an intraluteal amplification pathway between PGF2α and ET-1. Treatment with PGF2α induces ET-1 mRNA and protein in bovine CL [80], and conversely treatment with ET-1 will induce PGF2α production by luteal cells [81]. Thus, ET-1, as well as certain cytokine peptides, has complex but critical relationships with PGF2α and progesterone during luteolysis. Further research will be required to define the precise temporal sequence and intracellular mechanisms involved in the interrelationships of these peptides with the actions and production of intraluteal PGF2α and progesterone. Estradiol-17β, oxytocin, noradrenaline, and nitric oxide have also been found to stimulate intraluteal PG production (reviewed in [1]), and these could serve to amplify signals that reach luteal cells from extraluteal or intraluteal sources.

Possible Physiological Role of Intraluteal PG production

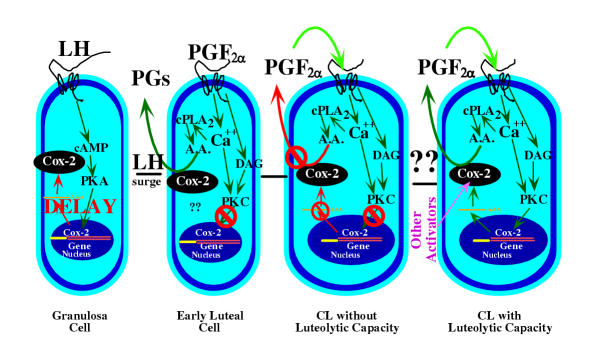

Figure 2 shows a simplified model for the regulation of PG production in the CL. The LH surge dramatically induces Cox-2 expression in the granulosa cells, and there is a subsequent increase in intrafollicular PG production. This induction is mediated by the cAMP/PKA intracellular effector system and there is a delay between the LH surge and Cox-2 expression [82]. The molecular mechanisms causing this delay in expression are unclear but this allows PG production to occur only a few hours before the time of ovulation [83]. This induction of Cox-2 is essential for ovulation as evidenced by the lack of ovulation in Cox-2 knock-out mice [84]. Binding of PGE2 to the EP2 receptor appears to be essential for normal ovulation [85].

Figure 2.

A model for the regulation of PG production during different stages of luteal differentiation. In the granulosa cell of the preovulatory follicle there is very low PG production and low expression of Cox-2. The LH surge induces Cox-2 expression through the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway but with a delay in expression depending upon the species [83]. In the early luteal cell there is high PG production that is stimulated by pathways that have not yet been defined. It is also possible that high Cox-2 protein has been left after the dramatic induction of Cox-2 after the LH surge. In the early luteal cell and in the CL without luteolytic capacity (these 2 stages may overlap), there are PGF2α receptors but PGF2α does not stimulate increased intraluteal PG production (shown by red lines). In addition, PGF2α does not induce other activators of PG production, such as decreased progesterone secretion, increased endothelin-1 production, or increased cytokine production. Unknown mechanisms cause the CL to acquire luteolytic capacity. After acquisition of luteolytic capacity, treatment with PGF2α increases intraluteal PG production. Activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) by increased free intracellular calcium concentrations provides arachidonic acid (A.A.) substrate to the induced Cox-2 enzyme. Although not shown, these events are likely to be localized to the nuclear membrane. Intraluteal PGF2α production activates an autoamplification loop in the mature CL due to PGF2α-induced Cox-2 expression and PGF2α induction of other activators of Cox-2 expression.

Within 2 days after the LH surge there is an induction of FP receptors in the CL [82]. The presence of FP receptor on the luteinized granulosa cells (large luteal cells) would allow response to PGF2α. However during this early time period, treatment with PGF2α does not cause luteolysis. As reviewed above, the CL of most species produce large amounts of PGs during the early luteal phase. The physiological importance of intraluteal PG production in the early CL is not clear. Okuda and Skarzynski [1] suggested that since luteal production of PGF2α is high in the early luteal phase of the cow, the early CL may be desensitized to PGF2α. If so, this would have to be a very specific desensitization, since PGF2α has been shown to stimulate a number of events in the early CL [63]. Treatment with indomethacin and sodium meclofenamate during the early to mid-luteal phase caused a decrease in circulating progesterone, suggesting a luteotropic role of luteal PGs [86,87]. However, it is also possible that one of these inhibitors, meclofenamate, had other direct effects on luteal cAMP or progesterone production that were independent of inhibition of PG production, as suggested by Zelinski-Wooten et al. [88]. Alternatively, perhaps luteotropic PGs, produced by the CL, protect the CL from luteolytic PGF2α during the early luteal phase. In addition, CL without luteolytic capacity appear to lack the pathways that induce intraluteal PGF2α production, suggesting that lack of these pathways is critical to protect the CL from luteolysis during the early luteal phase. Intraluteal PG production in the early CL may have numerous other physiological functions such as blood flow regulation, intercellular communication, or cellular differentiation that have not yet been clearly examined.

The physiological role of intraluteal PGF2α production in the luteolytic cascade has been frequently discussed. In species without involvement of the uterus in luteal regression it seems likely that intraluteal production of PGF2α may be a critical part of the luteolytic mechanism. In primates, as in other species, changes in the responsiveness of the corpus luteum to PGs as the corpus luteum ages may be as important as changes in luteal production of PGs [89,90]. In species with uterine-dependent regression of the CL, it seems clear that the luteolytic factor secreted by the uterus is PGF2α. However, the small amounts of uterine PGF2α could be dramatically amplified by intraluteal PGF2α production. As discussed above, this could be through direct effects of PGF2α on Cox-2 expression and induction of other PGF2α biosynthesis pathways (Section III). In addition, PGF2α would decrease luteal progesterone production and increase luteal cytokine and endothelin production; changes that have all been found to increase luteal PGF2α production (Section IV). Thus, luteal PGF2α production could serve to initiate (primates and possibly other species with uterine-independent luteal regression) or amplify (species with uterine-dependent luteal regression) the luteolytic cascade. The intriguing preliminary report by Griffeth et al. [67] raises the possibility that extraluteal signals (e.g., uterine PGF2α) may initiate the inhibition of progesterone production that accompanies luteal regression, but that the increase in intraluteal PGF2α production may be critical for the structural demise of the CL. In addition, intraluteal PGE2 production is increased to a similar extent as PGF2α production during luteolysis [91]. Similarly, we have consistently found intraluteal PGE2 and PGF2α production to be highly correlated (LA Anderson and MC Wiltbank, unpublished results). It seems likely that increased production of both PGs is mediated by the increased Cox-2 and PLA2 activity associated with luteolysis. A possible physiological role for increased intraluteal PGE during luteolysis is not clear; indeed, the PGE increase seems counterintuitive given the reported luteal protective effects of PGEs [92]. It seems clear that in spite of the substantial scientific progress that has been achieved in this research area in the past few years, there still remain numerous physiological and molecular questions related to intraluteal PG production.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by USDA 00-35203-9134 and the Wisconsin State Experiment Station to MCW. We would also like to acknowledge the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OARDC) Competitive Grants Program for support of the investigations of JSO. Salary and additional research support were provided by State and Federal funds appropriated to the OARDC, Ohio State University.

Contributor Information

Milo C Wiltbank, Email: wiltbank@calshp.cals.wisc.edu.

Joseph S Ottobre, Email: Ottobre.2@osu.edu.

References

- Okuda K, Skarzynski DJ. Luteal prostaglandin F2α: New concepts of prostaglandin F2α secretion and its actions within the bovine corpus luteum – Review. Asian – australas J Anim Sci. 2000;13:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J, Leung PCK. Auto/paracrine role of prostaglandins in corpus luteum function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;100:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JD, Lin L-L, Kriz RW, Ramesha CS, Sultzman LA, Lin AY, Milona N, Knopf JL. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 1991;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. BBA-Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijon MA, Leslie CC. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J Leukocyte Biol. 1999;65:330–336. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunt G, deWit J, vandenBosch H, Verkleij AJ, Boonstra J. Ultrastructural localization of cPLA2 in unstimulated and EGF/A23187-stimulated fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2449–2459. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.19.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LL, Wartmann M, Lin AY, Knopf JL, Seth A, Davis RJ. cPLA2 is phosphorylated and activated by MAP kinase. Cell. 1993;72:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90666-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurusu S, Sakaguchi S, Kawaminami M, Hashimoto I. Sustained activity of luteal cytosolic phospholipase A2 during luteolysis in pseudopregnant rats – Its possible implication in tissue involution. Endocrine. 2001;14:337–342. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:14:3:337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby DA, Moore AR, Colville-Nash PR. COX-1, COX-2, and COX-3 and the future treatment of chronic inflammatory disease. Lancet. 2000;355:646–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)12031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharan NV, Dai H, Roos KLT, Evanson NK, Tomsik J, Elton TS, Simmons DL. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: Cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13926–13931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162468699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun SS, Chen Z, Pace MC, Shaul PW. Glucocorticoids downregulate cyclooxygenase-1 gene expression and prostacyclin synthesis in fetal pulmonary artery endothelium. Circ Res. 1999;84:193–200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn SM, Schloemann S, Tessner T, Seibert K, Stenson WF. Crypt stem cell survival in the mouse intestinal epithelium is regulated by prostaglandins synthesized through cyclooxygenase-1. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1367–1379. doi: 10.1172/JCI119296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon LS. Role and regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during inflammation. Am J Med. 1999;106:37S–42S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ST, Gilbert RS, Xie WL, Luner S, Herschman HR. TGF-beta 1 inhibits both endotoxin-induced prostaglandin synthesis and expression of the TLS10/prostaglandin synthase-2 gene in murine macrophages. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;55:192–200. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Bingham CO, Matsumoto R, Austen KF, Arm JP. IgE-dependent activation of cytokine-primed mouse cultured mast-cells induces a delayed phase of prostaglandin D-2 generation via prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2. J Immunol. 1995;155:4445–4453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita I, Schindler M, Regier MK, Otto JC, Hori T, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. Different intracellular locations for prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-1 and synthase-2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10902–10908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seery LT, Nestor PV, FitzGerald GA. Molecular evolution of the aldo-keto reductase gene superfamily. J Molec Evol. 1998;46:139–146. doi: 10.1007/pl00006288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S-J, Wiltbank MC. Prostaglandin F2α induces expression of prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 in the ovine corpus luteum: a potential positive feedback loop during luteolysis. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1016–1022. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J, Norjavaara E, Selstam G. Synthesis of prostaglandin F2α, E2 and prostacyclin in isolated corpora lutea of adult pseudopregnant rats throughout the luteal life-span. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1992;46:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(92)90222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz FJ, Crenshaw TD, Wiltbank MC. Prostaglandin F2α induces distinct physiological responses in porcine corpora lutea after acquisition of luteolytic capacity. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1504–1512. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J, Shepherd TS, Dodson KS. Prostaglandin E2-9-ketoreductase in ovarian tissues. J Reprod Fertil. 1979;57:489–496. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0570489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintergalen N, Thole HH, Galla HJ, Schlegel W. Prostaglandin-E2 9-reductase from corpus-luteum of pseudopregnant rabbit is a member of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily featuring 20-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-activity. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.264_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin E, Fortier MA. Detection and regulation of the messenger for a putative bovine endometrial 9-keto-prostaglandin E2reductase: Effect of oxytocin and interferon-tau. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:125–131. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita RT, Okita JR. Prostaglandin-metabolizing enzymes during pregnancy: Characterization of NAD(+)-dependent prostaglandin dehydrogenase, carbonyl reductase, and cytochrome P450-dependent prostaglandin omega-hydroxylase. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;31:101–126. doi: 10.3109/10409239609106581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva PJ, Juengel JL, Rollyson MK, Niswender GD. Prostaglandin metabolism in the ovine corpus luteum: Catabolism of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) coincides with resistance of the corpus luteum to PGF2α. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1229–1236. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster VL. Molecular mechanisms of prostaglandin transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Pucci ML, Chan BS, Lu R, Ito S, Schuster VL. Prostaglandin transporter PGT is expressed in cell types that synthesize and release prostanoids. Amer J Physiol – Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F1103–F1110. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00152.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LE, Wu YL, Tsai SJ, Wiltbank MC. Prostaglandin F2α receptor in the corpus luteum: recent information on the gene, messenger ribonucleic acid, and protein. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1041–1047. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohn TT, Wong SM, Cotman CW, Cribbs DH. 15-Deoxy-Δ 12,14-prostaglandin J2, a specific ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, induces neuronal apoptosis. Neuroreport. 2001;12:839–843. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks JW, Forbes KK, Norland JF. Synthesis of prostaglandin F2 α by the ovary and uterus. J Reprod Med. 1972;9:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie HD, Rexroad CE., Jr Progesterone secretion and prostaglandin-F release in vitro by endometrial and luteal tissue of cyclic pigs. J Reprod Fert. 1980;60:157–163. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0600157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie HD, Rexroad CE, Jr, Bolt DJ. In vitro synthesis of progesterone and prostaglandin F by luteal tissue and prostaglandin F by endometrial tissue from the pig. Prostaglandins. 1978;16:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patek CE, Watson J. Factors affecting steroid and prostaglandin secretion by reproductive tissues of cycling and pregnant sows in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1983;755:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(83)90267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patek CE, Watson J. Prostaglandin F and progesterone secretion by porcine endometrium and corpus luteum in vitro. Prostaglandins. 1976;12:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(76)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexroad CE, Guthrie HD. Prostaglandin F2α and progesterone release in vitro by ovine luteal tissue during induced luteolysis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1979;112:639–644. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3474-3_71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milvae RA, Hansel W. Prostacyclin, prostaglandin F2α and progesterone production by bovine luteal cells during the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod. 1983;29:1063–1068. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod29.5.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothnick WB, Pate JL. Interleukin-1β is a potent stimulator of prostaglandin synthesis in bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:898–903. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.5.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson ED, Sertich PL. Secretion of prostaglandins and progesterone by cells from corpora lutea of mares. J Reprod Fert. 1990;88:223–229. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0880223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MS, Ottobre AC, Ottobre JS. Prostaglandin production by corpora lutea of rhesus monkeys: characterization of incubation conditions and examination of putative regulators. Biol Reprod. 1988;39:839–846. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JE, Friedman CI, Danforth DR. Interleukin-1 beta modulates prostaglandin and progesterone production by primate luteal cells in vitro. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:663–667. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan VV, Lanthier A. Luteal phase variations in endogenous concentrations of prostaglandins PGE and PGF and in the capacity for their in vitro formation in the human corpus luteum. Prostaglandins. 1985;30:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(85)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J, Selstam G. Changes in corpus luteum content of prostaglandin F2α and E in adult pseudopregnant rat. Prostaglandins. 1988;35:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(88)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Mitchell MD, Simpson ER. Secretion of progesterone and prostaglandins by cells of bovine corpora lutea from three stages of the luteal phase. J Endocrinol. 1988;118:121–126. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1180121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Acosta TJ, Hayashi K, Berisha B, Ozawa T, Ohtani M, Schams D, Miyamoto A. Intraluteal release of prostaglandin F2α and E2 during corpora lutea development in the cow. J Reprod Dev. 2002;48:583–590. doi: 10.1262/jrd.48.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazul AT, Kirsch JD, Slanger WD, Marchello MJ, Redmer DA. Prostalgndin F2α, oxytocin and progesterone secretion by bovine luteal cells at several stages of luteal development: effects of oxytocin, luteinizing hormone, prostaglandin F2α and estradiol-17β. Prostaglandins. 1989;38:307–318. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(89)90135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelVecchio RP, Sutherland WD, Sasser RG. Bovine luteal cell production in vitro of prostaglandin E2, oxytocin and progesterone in response to pregnancy-specific protein B and prostaglandin F2α. J Reprod Fert. 1996;107:131–136. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1070131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelVecchio RP, Sutherland WD, Sasser RG. Prostaglandin F2α, progesterone and oxytocin production by cultured bovine luteal cells treated with prostaglandin E2 and pregnancy-specific protein B. Prostaglandins. 1995;50:137–150. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(95)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelVecchio RP, Sutherland WD, Sasser RG. Effect of pregnancy-specific protein-B on luteal cell progesterone, prostaglandin, and oxytocin production during two stages of the bovine estrous cycle. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:2662–2668. doi: 10.2527/1995.7392662x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard BS, Ottobre JS. Progesterone and prostaglandin production by primate luteal cells collected at various stages of the luteal phase: modulation by calcium ionophore. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:401–408. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutt DA, Clarke AH, Fraser IS, Goh P, McMahon GR, Saunders DM, Shearman RP. Changes in concentration of prostaglandin F and steroids in human corpora lutea in relation to growth of the corpus luteum and luteolysis. J Endocrinol. 1976;71:453–454. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0710453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar R, Walters WAW. Human luteal tissue prostaglandins, 17β-estradiol, and progesterone in relation to the growth and senescence of the corpus luteum. Fetil Steril. 1983;39:298–303. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanston IA, McNatty KP, Baird DT. Concentration of prostaglandin F2α and steroids in the human corpus luteum. J Endocrinol. 1977;73:115–122. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0730115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friden BE, Wallin A, Brannstrom M. Phase-dependent influence of nonsteroidogenic cells on steroidogenesis and prostaglandin production by the human corpus luteum. Fetil Steril. 2000;73:359–365. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DE, Lei ZM, Rao CV. The enzymes in cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism in human corpora lutea: Dependence on luteal phase, cellular and subcellular distribution. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1991;43:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(91)90125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie HD, Rexroad CE, Jr, Bolt DJ. In vitro release of progesterone and prostaglandins F and E by porcine luteal and endometrial tissue during induced luteolysis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1979;112:627–632. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3474-3_69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XM, Carlson JC. Alterations in phospholipase A2 activity during luteal regression in pseudopregnant and pregnant rats. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2464–2468. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-5-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltbank MC, Guthrie PB, Mattson MP, Kater SB, Niswender GD. Hormonal regulation of free intracellular calcium concentrations in small and large ovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:771–778. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DB, Westfall SD, Fong HW, Roberson MS, Davis JS. Prostaglandin F2α stimulates the Raf/MEK1/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade in bovine luteal cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3876–3885. doi: 10.1210/en.139.9.3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltbank MC, Knickerbocker JJ, Niswender GD. Regulation of the corpus luteum by protein kinase C. I. Phosphorylation activity and steroidogenic action in large and small ovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1989;40:1194–1200. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod40.6.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Kot K, Ginther OJ, Wiltbank MC. Temporal gene expression in bovine corpora lutea after treatment with PGF2α based on serial biopsies in vivo. Reproduction. 2001;121:905–913. doi: 10.1530/reprod/121.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N, Kobayashi S, Roth Z, Wolfenson D, Miyamoto A, Meidan R. Administration of prostaglandin F2α during the early bovine luteal phase does not alter the expression of ET-1 and of its type A receptor: a possible cause for corpus luteum refractoriness. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:377–382. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YL, Wiltbank MC. Differential regulation of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 transcription in ovine granulosa and large luteal cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2001;65:103–116. doi: 10.1016/S0090-6980(01)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S-J, Wiltbank MC. Prostaglandin F2α regulates distinct physiological changes in early and mid-cycle bovine corpora lutea. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:346–352. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wiltbank MC. Differential effects of prostaglandin F2α on in vitro luteinized bovine granulosa cells. Reproduction. 2001;122:245–253. doi: 10.1530/reprod/122.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YL, Wiltbank MC. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene changes from protein kinase (PK) A- to PKC-dependence after luteinization of granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1505–1514. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.5.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wu MH, Chuang PC, Chen HM. Distinct regulation of gene expression by prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is associated with PGF2α resistance or susceptibility in human granulosa-luteal cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:415–423. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth RJ, Nett TM, Burns PD, Escudero JM, Inskeep EK, Niswender GD. Is luteal production of PGF2α required for luteolysis? Biol Reprod. 2002;66:465. [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL. Regulation of prostaglandin synthesis by progesterone in the bovine corpus luteum. Prostaglandins. 1988;36:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(88)90072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo DF, Pate JL. Tumor necrosis factor-α alters bovine luteal cell synthetic capacity and viability. Endocrinology. 1992;130:854–860. doi: 10.1210/en.130.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townson DH, Pate JL. Regulation of prostaglandin synthesis by interleukin-1β in cultured bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1994;51:480–485. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townson DH, Pate JL. Mechanism of action of TNF-α-stimulated prostaglandin production in cultured bovine luteal cells. Prostaglandins. 1996;52:361–373. doi: 10.1016/S0090-6980(96)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL. Involvement of immune cells in regulation of ovarian function. J Reprod Fertil. 1995;49:365–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narko K, Ritvos O, Ristimaki A. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin F2α receptor expression by interleukin-1 beta in cultured human granulosa-luteal cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3638–3644. doi: 10.1210/en.138.9.3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild DL, Pate JL. Modulation of bovine luteal cell synthetic capacity by interferon-gamma. Biol Reprod. 1991;44:357–363. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff MG, Petroff BK, Pate JL. Mechanisms of cytokine-induced death of cultured bovine luteal cells. Reproduction. 2001;121:753–760. doi: 10.1530/reprod/121.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milvae RA. Inter-relationships between endothelin and prostaglandin F2α in corpus luteum function. Rev Reprod. 2000;5:1–5. doi: 10.1530/revreprod/5.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girsh E, Milvae RA, Wang W, Meidan R. Effect of endothelin-1 on bovine luteal cell function: Role in prostaglandin F2α-induced antisteroidogenic action. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1306–1312. doi: 10.1210/en.137.4.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinckley ST, Milvae RA. Endothelin-1 mediates prostaglandin F-2 alpha-induced luteal regression in the ewe. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1619–1623. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto A, Kobayashi S, Arata S, Ohtani M, Fukui Y, Schams D. Prostaglandin F2α promotes the inhibitory action of endothelin-1 on the bovine luteal function in vitro. J Endocrinol. 1997;152:R7–R11. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.152r007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girsh E, Wang W, Mamluk R, Arditi F, Friedman A, Milvae RA, Meidan R. Regulation of endothelin-1 expression in the bovine corpus luteum: Elevation by prostaglandin F2α. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5191–5196. doi: 10.1210/en.137.12.5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F, Minici F, Pardo MG, Navarra P, Proto C, Mancuso S, Lanzone A, Apa R. Endothelins enhance prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2α) biosynthesis and release by human luteal cells: Evidence of a new paracrine/autocrine regulation of luteal function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:811–817. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.2.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wiltbank MC, Bodensteiner KJ. Distinct mechanisms regulate induction of messenger ribonucleic acid for prostaglandin (PG) G/H synthase-2, PGE (EP3) receptor, and PGF2α receptor in bovine preovulatory follicles. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3348–3355. doi: 10.1210/en.137.8.3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois J, Dore M. The late induction of prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 in equine preovulatory follicles supports its role as a determinant of the ovulatory process. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4427–4434. doi: 10.1210/en.138.10.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BJ, Lennard DE, Lee CA, Tiano HF, Morham SG, Wetsel WC, Langenbach R. Anovulation in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice is restored by prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-1β. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2685–2695. doi: 10.1210/en.140.6.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Ma WG, Smalley W, Trzaskos J, Breyer RM, Dey SK. Diversification of cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandins in ovulation and implantation. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1557–1565. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.5.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent EL, Baughman WL, Novy MJ, Stouffer RL. Intraluteal infusion of a prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor, sodium meclofenamate, causes premature luteolysis in rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2261–2269. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-5-2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulghesu AM, Lanzone A, Di Simone N, Nicoletti MC, Caruso A, Mancuso S. Indomethacin in vivo inhibits the enhancement of the progesterone secretion in response to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone by human corpus luteum. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:35–39. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski-Wooten MB, Sargent EL, Molskness TA, Stouffer RL. Disparate effects of the prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, meclofenamate, and flurbiprofen on monkey luteal tissue in vitro. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1380–1387. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-3-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottobre JS, Houmard BS, Stokes BT, Guan Z. The phosphatidylinositol system in the primate corpus luteum: possible role in luteal regression. In: Puri CP, Van Look PFA, editor. In Current Concepts in Fertility Regulation and Reproduction. New Delhi: Wiley Eastern Limited; 1994. pp. 463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Michael AE, Abayasekara DRE, Webley GE. Cellular mechanisms of luteolysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;99:R1–R9. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Acosta TJ, Berisha B, Kobayashi S, Ohtani M, Schams D, Miyamoto A. Changes in prostaglandin secretion by the regressing bovine corpus luteum. Prostag Other Lipid Mediat. 2003;70:339–49. doi: 10.1016/S0090-6980(02)00148-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magness RR, Huie JM, Weems CW. Effect of contralateral and ipsilateral intrauterine infusion of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) on luteal function in the nonpregnant ewe. J Anim Sci. 1978;47:376. [Google Scholar]