Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has claimed 349 lives with 5,327 probable cases reported in mainland China since November 2002. SARS case fatality has varied across geographical areas, which might be partially explained by air pollution level.

Methods

Publicly accessible data on SARS morbidity and mortality were utilized in the data analysis. Air pollution was evaluated by air pollution index (API) derived from the concentrations of particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and ground-level ozone. Ecologic analysis was conducted to explore the association and correlation between air pollution and SARS case fatality via model fitting. Partially ecologic studies were performed to assess the effects of long-term and short-term exposures on the risk of dying from SARS.

Results

Ecologic analysis conducted among 5 regions with 100 or more SARS cases showed that case fatality rate increased with the increment of API (case fatality = - 0.063 + 0.001 * API). Partially ecologic study based on short-term exposure demonstrated that SARS patients from regions with moderate APIs had an 84% increased risk of dying from SARS compared to those from regions with low APIs (RR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.41–2.40). Similarly, SARS patients from regions with high APIs were twice as likely to die from SARS compared to those from regions with low APIs. (RR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.31–3.65). Partially ecologic analysis based on long-term exposure to ambient air pollution showed the similar association.

Conclusion

Our studies demonstrated a positive association between air pollution and SARS case fatality in Chinese population by utilizing publicly accessible data on SARS statistics and air pollution indices. Although ecologic fallacy and uncontrolled confounding effect might have biased the results, the possibility of a detrimental effect of air pollution on the prognosis of SARS patients deserves further investigation.

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is an emerging viral infectious disease, which has claimed 349 lives with 5,327 probable cases reported in mainland China since November 2002. [1,2] SARS case fatality has varied across geographical areas with higher fatality found in the northern areas of China. The SARS case fatalities of Beijing and Tianjin, two cities in the northern part of China, were 7.66% and 8%, respectively; while the case fatality rate of Guangdong, a province in the southern part of china was only 3.84%. Although sex ratio, age distribution, socioeconomic level, availability of health facilities, and clinical practices might be responsible for the geographical difference, air pollution could be an important determinant. Air pollution has been linked to acute respiratory inflammation, asthma attack, COPD exacerbation, and death from cardiorespiratory diseases by various studies. [3-6] In this study, the relationship between air pollution and SARS case fatality was explored via an ecologic study design.

Methods

Publicly accessible data on SARS morbidity and mortality were utilized in the study. [2] Case fatality was estimated by dividing the number of reported deaths by the number of probable cases. Air pollution was evaluated by air pollution index (API) provided by the Chinese National Environmental Protection Agency (CNEPA). [7] CNEPA calculated individual pollution indices for five major air pollutants including particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ground-level ozone (O3), and carbon monoxide (CO). The maximal individual pollution index was set as the comprehensive API for the monitoring area. In most of monitoring areas, PM10 was considered as a major pollutant. [7]

API could be categorized into seven groups with 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 as the cut-off points. APIs less than 100 were thought healthy for general population. Since the majority of patients were diagnosed during April and May, the average of daily APIs collected within these months in each region was used for data analyses mainly. In addition, to evaluate potential influence of long-term exposure to air pollution on the case fatality rate, the average of APIs between June 2000 and October 2002 before SARS epidemic was also analyzed.

Ecologic analysis was conducted to explore the correlation and association between air pollution during April and May 2003 and SARS case fatality. A linear model was fitted to the data among five regions with 100 cases or more. Furthermore, we conducted data analysis by grouping SARS patients into three exposure levels and evaluating short-term exposure (April-May 2003) and long-term exposure (June 2000-October 2002), respectively. The cut-off points were 75 and 100 API. Case fatalities of patients from regions with high APIs (API>100) and patients from regions with moderate APIs (75–100) were compared to that of patients from regions with low APIs (API<75). Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Monotonic trend test with exposure scored as 1, 2, and 3 for each exposure group was also conducted to investigate whether case fatalities increased with the increase of APIs. All data analyses were performed in Statistical Analysis Software (SAS).

Results

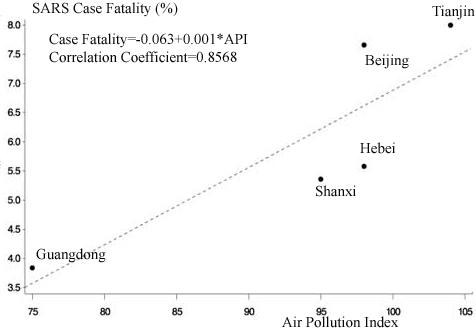

During the epidemic, 5,327 Chinese were diagnosed as SARS probable cases. Among them, 349 died from the disease and the rest recovered, which accounted for the case fatality of 6.55%. The average APIs ranged from 52 to 126 for different regions during April and May 2003. Ecologic analysis was conducted among 5 regions with 100 or more SARS cases (Guangdong, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, and Tianjin) to explore the relationship between air pollution and SARS case fatality. Inner Mongolia, which had 282 probable cases, was excluded from the analysis due to poor data quality reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control. [8] 4,870 SARS cases occurred in these five regions, which represented 91.4% of all cases in China. The APIs of Guangdong, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, and Tianjin during April and May were 75, 95, 98, 99, and 104, and the corresponding fatality were 3.84%, 5.36%, 5.58%, 7.66% and 8%, respectively. Data were fitted to the linear model: case fatality = -0.063+0.001*API, showing case fatality rates increased with the increment of API. The correlation coefficient between air pollution index and SARS fatality was 0.8568 (p = 0.0636). (See figure 1)

Figure 1.

The Correlation and Association between Short-term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Case Fatality of SARS in People's Republic of China.

According to the air pollution data during April and May 2003, a total of 1,546 patients resided in regions with low APIs, 63 of whom died from SARS. Among 3,590 patients from regions with moderate APIs, 269 died from the disease. 17 out of 191 patients from regions with high APIs also died. The corresponding fatalities were 4.08%, 7.49% and 8.90%, respectively. SARS patients from regions with moderate APIs had an 84% increased risk of dying from SARS compared to those from regions with low APIs (RR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.41–2.40). Similarly, SARS patients from regions with high APIs were twice as likely to die from SARS compared to those from regions with low APIs. (RR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.31–3.65). The trend test showed that SARS case fatality increased with the increase of air pollution level (P for trend <0.001). (See Table 1)

Table 1.

The Effect of Short-term Exposure to Air Pollution (April-May 2003) on the Risk of Dying from SARS in Chinese Population.

| API | Number of Deaths | Number of recovered | Total Number of Cases | Case Fatality | RR & 95% CI |

| >100 | 17 | 174 | 191 | 8.90% | 2.18 (1.31–3.65) |

| 75–100 | 269 | 3321 | 3590 | 7.49% | 1.84 (1.41–2.40) |

| <75 | 63 | 1483 | 1546 | 4.08% | 1 |

| Total | 349 | 4978 | 5327 | 6.53% |

We also studied the effect of long-term average air pollution before SARS epidemic on SARS fatality. According to the air pollution data between June 2000 and October 2002, 67 out of 1,572 patients from regions with low APIs died from SARS. While, 35 out of 363 from regions with moderate APIs and 247 out of 3,392 from regions with high APIs died from SARS, respectively. The corresponding fatalities were 4.26%, 9.64% and 7.28%, respectively. The risk ratios comparing high and moderate API group to low API group were 1.71 (95%CI: 1.34–3.33) and 2.26 (95%CI: 1.53–3.35), respectively. The results showed that long-term exposure to air pollution was positively associated with SARS case fatality, even though there was no apparent trend. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

The Effect of Long-term Exposure to Air Pollution (June 2000-October 2002) on the Risk of Dying from SARS in Chinese Population.

| API | Number of Deaths | Number of recovered | Total Number of Cases | Case Fatality | RR & 95% CI |

| >100 | 247 | 3145 | 3392 | 7.28% | 1.71 (1.34–3.33) |

| 75–100 | 35 | 328 | 363 | 9.64% | 2.26 (1.53–3.35) |

| <75 | 67 | 1505 | 1572 | 4.26% | 1 |

| Total | 349 | 4978 | 5327 | 6.53% |

Discussion

Our analyses showed that air pollution was associated with increased risk of dying from SARS. The biological explanation might be that long-term or short-term exposure to certain air pollutants could compromise lung function, therefore increasing SARS fatality. Both long-term and short-term exposure to air pollution has been associated with a variety of adverse health effects including acute respiratory inflammation, asthma and COPD. [3-6,9] Air pollution may predispose the respiratory epithelium of SARS patients, leading to severe respiratory symptoms and an increased risk of deaths. The adverse effect of exposure to particulate matter less than 10 microns in aerodynamic diameter (PM10) has been studies extensively. [10] A study done in US on the long-term effects of air pollution showing that each 10 micrograms/m3 elevation in PM10 accounted for 6% of increased risk of cardiopulmonary mortality. [11] Exposure to PM10 was also linked to asthma and bronchitis. Data from CNEPA showed that PM10 was the major pollutant for most monitoring areas. [7] We hypothesized that exposure to air pollutants, such as particulate matters (PM10), might influence the prognosis of SARS and lead to increased risk of deaths.

This study was subject to several limitations. First, ecologic study designs were adopted in the study, which might be subject to ecologic fallacy. [12,13] Furthermore, we couldn't predict the direction and magnitude of the bias because of no access of the data at the individual level. Second, we had no data on the joint distribution between air pollution and potential confounders such as socioeconomic status, smoking status, age, and gender; therefore, no confounding effects could be evaluated or controlled for. The uneven application of dangerous therapy and difference in medical facilities by region might also account for the variation of case fatality. But they might not fully explain the observed association because the same therapies were recommended by the Chinese Health Ministry and CDC and followed by medical practitioners in the country. Data showed that cases from Beijing had relatively higher case fatality, although this capital city might have provided better medical support to SARS patients. Third, we assumed that air pollution was evenly distributed within each region so that we could use monitoring data colleted within each region as individual's surrogate exposure to ambient air pollutants. Exposure misclassification might have biased the study results due to the imprecise measurements. Nevertheless, this is the first observation showing that air pollution is associated with increased fatality of SARS patients in Chinese population, which deserves further investigation and might have certain impact on the study of SARS nature history.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a positive association between levels of air pollution and SARS case fatality in Chinese population by analyzing SARS data and air pollution indices. Although the interpretation of this association remains uncertain, the possibility of a detrimental effect of air pollution on the prognosis of SARS patients deserves further investigation.

List of Abbreviations

SARS: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

API: Air Pollution Index

CNEPA: Chinese National Environmental Protection Agency

PM10: Particulate Matter

SO2: Sulfur Dioxide

NO2: Nitrogen Dioxide

CO: Carbon Monoxide

O3: Ozone

RR: Risk Ratio

CI: Confidence Interval

SAS: Statistical Analysis Software

Competing Interests

None declared.

Authors' Contributions

Yan Cui was responsible for data analysis, summarization of results, and manuscript preparation. Zuo-Feng Zhang took the overall responsibility in hypothesis generation, study design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript preparation. John Friones was involved in the generation of hypothesis, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. Jinkou Zhao and Hua Wang were involved in data collection and manuscript preparation. Shun-Zhang Yu was involved in generation of hypothesis and study design, and manuscript preparation. Roger Detels was involved in generation of hypothesis and study design, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1476-069x-2-15-b1.pdf

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grant number ES 011667 from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, CA90833 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, by the Southern California Particle Center and Supersite, housed in the UCLA School of Public Health and the Institute of the Environment at UCLA, the UCLA Center for Occupational and Environmental Health, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency STAR Program (Grant no. R82735201).

Contributor Information

Yan Cui, Email: yancui@ucla.edu.

Zuo-Feng Zhang, Email: zfzhang@ucla.edu.

John Froines, Email: jfroines@ucla.edu.

Jinkou Zhao, Email: jkzhao@hotmail.com.

Hua Wang, Email: jkzhao@hotmail.com.

Shun-Zhang Yu, Email: szyu@shmu.edu.cn.

Roger Detels, Email: detels@ucla.edu.

References

- Cumulative Number of Reported Probable Cases of SARS (From: Nov 1st, 2002 To: August 7th, 2003) World Health Organization, Communicable Disease Surveillance & Response (CSR) 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003_08_15/en/

- Nationwide SARS statistics in China. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. http://www.chinacdc.net.cn/feiyan/data/8.20.htm

- Bates DV, Baker-Anderson M, Sizto R. Asthma attack periodicity: a study of hospital emergency visits in Vancouver. Environ Res. 1990;51:51–70. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz j, Dockery DW. Particulate air pollution and daily mortality in Steubenville, Ohio. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:12–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Pope CA. Acute respiratory effects of particulate air pollution. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:107–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Slater D, Larson TV, Pierson WE, Koenig JQ. Particulate air pollution and hospital emergency room visits for asthma in Seattle. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:826–31. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Definition and Classification of Air Pollution Index (API). Chinese Environmental Protection Agency and the API data were obtained from http://www.zhb.gov.cn/quality/background.php http://www.zhb.gov.cn/quality/background.php.

- Epidemic Analysis Group, SARS Prevention and Control Unit Analytical Report of SARS Epidemic in China, 4/22-5/10, 2003. Chinese CDC Report.

- Detels R, Tashkin DP, Sayre JW, Rokaw SN, Coulson AH, Massey FJ, Jr, Wegman DH. The UCLA population studies of chronic obstructive respiratory disease. 9. Lung function changes associated with chronic exposure to photochemical oxidants; a cohort study among never-smokers. Chest. 1987;92:594–603. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz MD. Epidemiological studies of the respiratory effects of air pollution. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1029–54. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09051029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, Thurston GD. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork J, Stromberg U. Effects of systematic exposure assessment errors in partially ecologic case-control studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:154–60. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster T. Commentary: Does the spectre of ecologic bias haunt Epidemiology? Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:161–2. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]