Abstract

Francisella tularensis is the etiologic agent of the highly infectious animal and human disease tularemia. Its extreme infectivity and virulence are associated with its ability to evade immune detection, which we now link to its robust reactive oxygen species-scavenging capacity. Infection of primary human monocyte-derived macrophages with virulent F. tularensis SchuS4 prevented proinflammatory cytokine production in the presence or absence of IFN-γ compared with infection with the attenuated live vaccine strain. SchuS4 infection also blocked signals required for macrophage cytokine production, including Akt phosphorylation, IκBα degradation, and NF-κB nuclear localization and activation. Concomitant with SchuS4-mediated suppression of Akt phosphorylation was an increase in the levels of the Akt antagonist PTEN. Moreover, SchuS4 prevented the H2O2-dependent oxidative inactivation of PTEN compared with a virulent live vaccine strain. Mutation of catalase (katG) sensitized F. tularensis to H2O2 and enhanced PTEN oxidation, Akt phosphorylation, NF-κB activation, and inflammatory cytokine production. Together, these findings suggest a novel role for bacterial antioxidants in restricting macrophage activation through their ability to preserve phosphatases that temper kinase signaling and proinflammatory cytokine production.

Keywords: Akt PKB, Bacteria, Immunology, NF-κB, Oxidative Stress, Antioxidants, Francisella, PTEN

Introduction

Francisella tularensis is a Gram-negative intracellular bacterium that is the causative agent of the disease tularemia. F. tularensis is considered a potential biological weapon because of its extreme infectivity, ease of artificial dissemination via aerosols, and substantial capacity to cause illness and death (1). F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (strain SchuS4) is a category A biological agent and the most virulent for humans, with an estimated infectious dose of <10 colony-forming units, whereas the attenuated live vaccine strain (LVS)2 of subsp. holarctica displays little virulence in humans. Upon infection, F. tularensis engages and rapidly tempers a number of diverse host cell signaling networks to allow for its intracellular survival and replication (2, 3). Among these is the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway, which plays a prominent role in restricting lethal infection and inflammatory cytokine production in response to F. tularensis (4). Parsa et al. (5) demonstrated that conversion of phosphoinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate to phosphoinositol 3,4-bisphosphate by the 5′-phosphatase SHIP negatively regulates macrophage cytokine production in response to Francisella novicida. Thus, SHIP limits phosphoinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate production, Akt activation, and subsequent cytokine production in response to infection. Recent microarray analysis from the Tridandapani and co-workers has revealed that the activity of Akt is also suppressed by SchuS4 (6) and correlates with the production of microRNAs that target SHIP expression (7). In addition, F. tularensis infection increases the levels of the dual-lipid protein phosphatase and Akt antagonist PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) (8). Together, these findings suggest that suppression of Akt signaling likely plays an important role in the intracellular survival of F. tularensis.

Both Akt and NF-κB are key determinants in regulating macrophage cytokine production and are amenable to redox control. Reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species have emerged as key mediators in the regulation of signaling networks by their ability to modulate phosphatase activity, kinase cascades, and transcription factor binding. The principle mediator of ROS-dependent signaling is the 2e− reduction product of oxygen (O2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is produced in response to numerous physiologic stimuli. H2O2 reversibly oxidizes active-site cysteines in many protein-tyrosine phosphatases, generating a sulfenic derivative (Cys-SOH) that is sensitive to reduction, including the active site of PTEN (9–11). Redox triggers also regulate the activity of NF-κB at multiple levels, ultimately controlling transcription of its target genes (9, 12). Moreover, both NF-κB-dependent cytokine production and Akt play an important role in clearance of Francisella from the host (4–6).

Recent evidence indicates that virulent SchuS4 is highly resistant to both ROS/reactive nitrogen species and is armed with a variety of antioxidant enzymes to detoxify environmental and host-derived ROS/reactive nitrogen species and contribute to virulence (13). Here, we demonstrate that F. tularensis antioxidant-scavenging systems restrict inflammatory cytokine gene expression by inhibiting both Akt and NF-κB activation. F. tularensis-dependent inhibition of Akt activation is associated with its ability to suppress the oxidative inhibition of PTEN. These findings indicate that a prominent redox component to the immunopathogenesis of F. tularensis exists and unveil a new paradigm for how bacterial antioxidants serve to restrict host inflammatory responses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Media

F. tularensis subsp. holarctica LVS (ATCC 29684, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was used in this study. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (strain SchuS4), originally isolated from a human case of tularemia, was obtained from the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (Frederick, MD). The catalase mutant (ΔkatG) was kindly provided by Dr. Anders Sjöstedt. All experiments utilizing SchuS4 were conducted within a Centers for Disease Control-certified ABSL-3/BSL-3 facility at Albany Medical College. All bacteria were grown on chocolate agar plates supplemented with IsoVitaleX (BD) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Bacteria were grown in Mueller Hinton broth supplemented with IsoVitaleX in a shaking incubator (160 rpm) at 37 °C where indicated.

Primary human monocytes were purchased from the University of Nebraska (Lincoln, NE) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with l-glutamine, 10% human serum (Fisher), and colony-stimulating factor-1 (R&D Systems). The medium was half-exchanged on days 2 and 4, and human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) were infected on day 7. Recombinant human IFN-γ was used at 100 units/ml, and macrophages were pretreated with IFN-γ for 18 h prior to infection.

Human HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells (ATCC CCL-121) were cultured in Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. U937 cells (ATCC CRL-1593.2) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with l-glutamine (HyClone) and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were treated with 1 μg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 3-acetate and incubated for 2 days prior to infection for terminal differentiation. All cells were cultured in a 37 °C humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Antibodies

Antibodies against phospho-PTEN (Ser380/Thr387/Thr383), total PTEN, and phospho-Akt (Ser473) were purchased from Cell Signaling. Anti-total Akt1/2 antibody was purchased from Calbiochem. All NF-κB pathway antibodies (anti-phospho-IκBα, anti-total IκBα, and anti-p65) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Applied Biosystems) was used as a loading control.

Macrophage Invasion Assay

Intracellular bacteria were quantified as described previously (14).

Cytokine Analysis

Culture supernatants from macrophage invasion assays were collected 24 and 48 h post-infection, and TNF-α and IL-6 levels were quantified using cytometric bead array human flex sets (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed using a FACSArray bioanalyzer and FCAP Array software. The results are expressed as pg/ml.

Western Blot Analysis

Macrophages were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 100 for all experiments. At a given time point (0–4 h), macrophages were lysed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Nonidet P-40. Protein concentrations were determined using BCA standards (Pierce), and 25 μg of proteins was electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Novex 4–12% BisTris, Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked with 5% nonfat milk (in 1% Tween/Tris-buffered saline) for 1 h at room temperature. Antibodies were diluted 1:1000 in 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Western blots were developed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000; GE Healthcare) and detected by incubating membranes with ECL solution (Pierce), followed by exposure to x-ray film. For identification of reduced and oxidized PTEN, cells were lysed in 0.15 ml of 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing 2% SDS and 40 mm N-ethylmaleimide and electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel under nonreducing conditions.

Luciferase Assay

The NF-κB-luciferase and Renilla constructs were transfected into HT1080 cells 24 h prior to infection as described previously (15). In brief, cells were infected for 4 h at a multiplicity of infection of 100 with LVS or ΔkatG. After 2 h, cells are treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) where indicated. The cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was monitored using a Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla levels, and results are expressed as percent luciferase activity.

Immunofluorescence Staining

hMDMs were cultured on glass coverslips with colony-stimulating factor-1. On day 7, macrophages were infected with LVS, ΔkatG, or SchuS4 for 20 min. TNF-α (10 ng) was added 5 min after the initial infection where indicated. Following infection, cells were fixed and permeabilized with 1:1 methanol/acetone mixture. Slides were blocked with 3% fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min and incubated with anti-rabbit p65 antibodies (1:200 in 3% fetal bovine serum; Cell Signaling) for 1 h, followed by goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488 for 30 min. Coverslips were mounted with antifade medium (ProLong Gold, Invitrogen) onto glass slides, and fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope.

Bacterial Growth Curves

Growth curves were generated as described previously (14). Briefly, F. tularensis strains were streaked on chocolate agar plates and grown for ∼36 h at 37 °C. Single colonies were picked and grown to A600 = 0.20 in 10 ml of Mueller Hinton broth, and 180 μl of each bacterial culture was added to a 96-well plate in quadruplicate. H2O2 was added to the appropriate wells at various concentrations. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C with rocking (160 rpm) for 24 h, and the absorbance was measured at 6-h intervals using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader.

3-Amino-1,2,4-triazole-dependent Inhibition of Catalase to Determine Intracellular H2O2

hMDMs were infected with F. tularensis strains for 30 min, followed by treatment with 20 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma) for 0, 5, 10, or 15 min. Following treatment, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 0.05 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), sonicated, and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. Catalase activity was measured based on the method of Claiborne (16), and H2O2 concentrations were determined as described previously (17).

Analysis of Intracellular Redox State

The redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein roGFP1 was designed with two surface-exposed cysteine residues that are sensitive to oxidation by ROS (18). The oxidation of roGFP1 changes the protonation state of the chromophore, shifting the excitation from 470 to 400 nm while the emission wavelength remains constant (510 nm). The human U937 macrophage cell line was transiently transfected with roGFP1 using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and maintained for 24 h prior to infection. Cells were infected with either LVS or ΔkatG. GFP fluorescence was monitored following 15 and 45 min of infection and determined using the Zeiss Axio microscope. At least 10 different fields were marked and photographed. The software was then used to determine excitation at 410 and 470 nm, and the ratio was determined. Increases in the 410/470-nm ratios are indicative of greater oxidation.

RESULTS

SchuS4 Suppresses Proinflammatory Cytokine Production and Resists Killing by IFN-γ-stimulated hMDMs

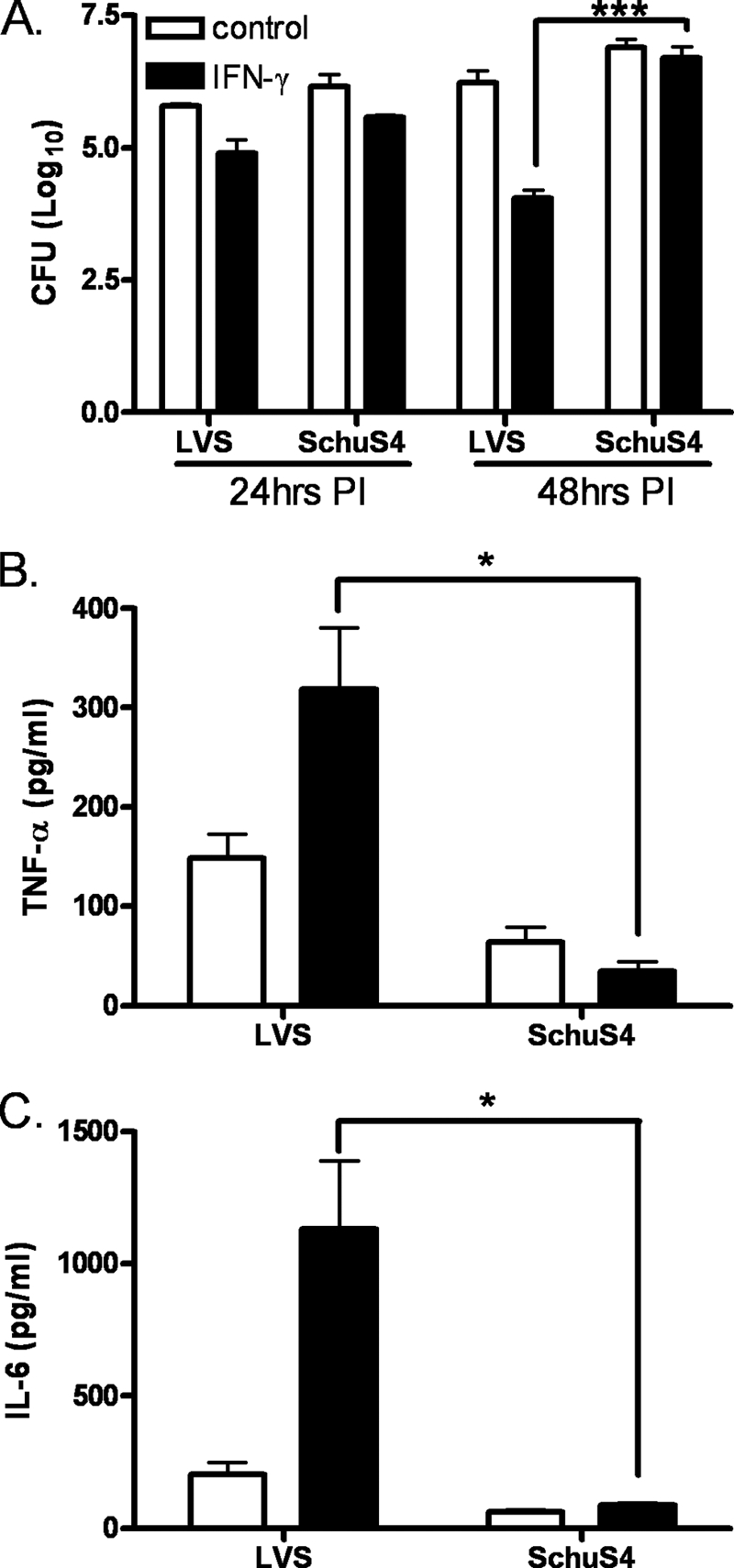

IFN-γ plays a critical role in protection from F. tularensis LVS and F. novicida by its ability to enhance the production of proinflammatory cytokines from infected murine macrophages (19, 20). However, whether virulent SchuS4 elicits a similar response in hMDMs is not known. Infection of hMDMs revealed that LVS growth was impaired in response to IFN-γ treatment compared with SchuS4. Both F. tularensis strains grew comparably well in unstimulated hMDMs (Fig. 1A). Supernatants from LVS-infected hMDMs displayed modest increases in TNF-α and IL-6 levels, which were significantly enhanced upon IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 1, B and C). In contrast, SchuS4 infection failed to elicit the production of IL-6 and TNF-α in unstimulated or IFN-γ-stimulated hMDMs. These results indicate that SchuS4 subverts IL-6 and TNF-α production upon infection, which is associated with its ability to resist IFN-γ-dependent killing.

FIGURE 1.

SchuS4 inhibits proinflammatory cytokines in unstimulated and IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages. hMDMs were infected with LVS or SchuS4. Cells were lysed at 24 or 48 h post-infection (PI), and intracellular bacteria were quantified (A). TNF-α (B) and IL-6 (C) levels were measured in the culture supernatants 24 h post-infection using the BDTM cytometric bead array. The statistical significance of the results was examined with Student's t test, and p values were recorded. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 compared with infection with LVS (n = 6). CFU, colony-forming units.

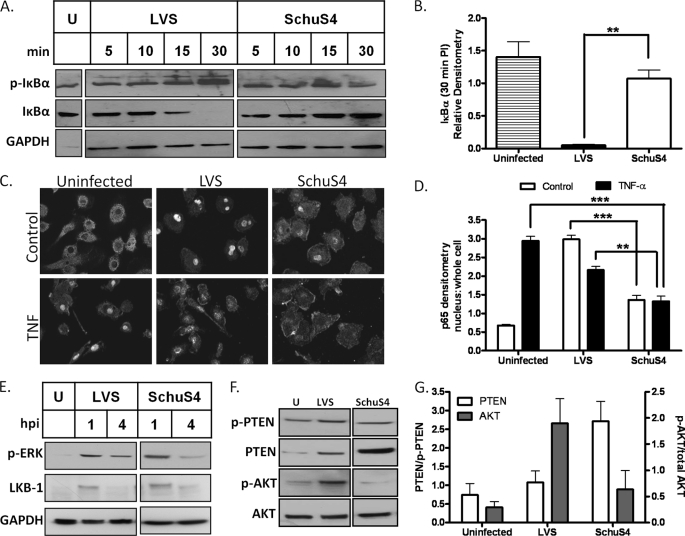

F. tularensis Subspecies Differ in Their Capacity to Drive NF-κB Signaling

NF-κB is composed of a family of closely related transcription factors required for expression of genes involved in inflammation and the immune response, including TNF-α and IL-6 (21). We investigated whether subversion of IL-6 and TNF-α production by SchuS4 is associated with alterations in NF-κB signaling events. Kinetic analysis of IκBα post-infection revealed a gradual increase in phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of this NF-κB inhibitory protein in LVS- relative to SchuS4-infected hMDMs (Fig. 2, A and B). Phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα resulted in release and translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit to the nucleus, which led to gene activation. Immunofluorescence staining of the p65 subunit 20 min post-infection revealed a marked difference in the degree of p65 nuclear localization between LVS and SchuS4 (Fig. 2C). SchuS4 also inhibited the TNF-α-induced translocation of p65. Nuclear localization of p65 in response to LVS infection was comparable with that mediated by TNF-α, whereas SchuS4 partially blocked TNF-α-mediated p65 translocation in infected hMDMs. The intensity of nuclear translocation was measured by comparing the ratio of nuclear to whole cell staining indicated that p65 nuclear localization diminished upon infection with SchuS4 relative to LVS or treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

SchuS4 restricts NF-κB and Akt signaling pathways. A, hMDMs were stimulated with IFN-γ for 18 h prior to infection with LVS or SchuS4 for the indicated times. IκBα degradation and phosphorylation were determined by Western blot analysis. U, uninfected; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, shown are the results from the densitometric analysis of IκBα degradation 30 min post-infection (n = 3). C, shown is the nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit in IFN-γ-simulated hMDMs infected with LVS or SchuS4 with or without 10 ng of TNF-α for 20 min post-infection by immunofluorescence. D, the quantification of p65 localization was calculated and is expressed as the ratio of nuclear to whole cell staining (n = 20). E, IFN-γ-stimulated hMDMs were infected with LVS or SchuS4 for 1 or 4 h. Erk phosphorylation and LKB-1 levels were assayed by Western blotting. hMDMs were infected with LVS or SchuS4 for 1 h. Total and phospho-PTEN and total and phospho-Akt levels were monitored by Western blot analysis. hpi, hours post-infection. G, shown are the results from densitometric analysis of the bands shown in F expressed as ratios of total PTEN to phospho-PTEN and of phospho-Akt to total Akt. The data are cumulative of three independent experiments. The statistical analyses were performed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test, and p values were recorded. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

We next determined whether the tempered NF-κB response to SchuS4 also impairs other signaling networks that are activated upon infection. Analysis of Erk1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2) and serine/threonine kinase 11 (LKB-1) showed no differences in the rate of activation in response to infection with either SchuS4 or LVS (Fig. 2E). These findings indicate that although NF-κB signaling is more efficiently tempered by SchuS4, not all signaling responses are differentially sensitive to infection with distinct F. tularensis subspecies.

Infection with SchuS4 Suppresses Akt Activation by Increasing PTEN Levels

We next evaluated whether the failure of IFN-γ-stimulated hMDMs to produce cytokines in response to infection with SchuS4 is associated with alterations in the Akt signaling network, a critical upstream signal mediator of NF-κB activation (22). The levels of active Akt (phosho-Akt) were attenuated following infection with SchuS4 relative to LVS at both 1 and 4 h post-infection, with no associated increase in total Akt levels (Fig. 2F). Analysis of the negative regulator of Akt, PTEN, revealed an increase in total PTEN relative to phospho-PTEN, which is suggestive of an increase in its overall activity. Quantitative analysis of PTEN/phospho-PTEN ratios revealed increases following infection with SchuS4 that were not observed in response to LVS (Fig. 2G). Moreover, increases in PTEN were associated with suppression of phospho-Akt in response to SchuS4, whereas LVS displayed an increase in phospho-Akt.

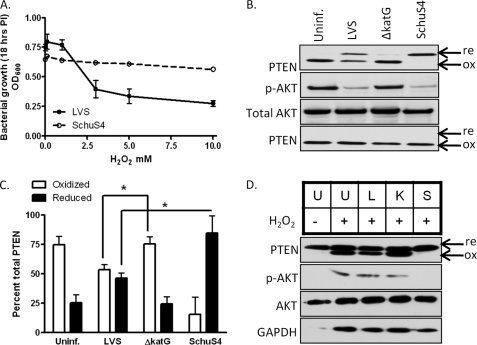

F. tularensis Antioxidants Contribute to Impairment of Host Cell Signaling

Our analysis of the sensitivity of F. tularensis LVS and SchuS4 to increasing concentrations of H2O2 supported the findings of Lindgren et al. (13), indicating that SchuS4 is unusually resistant to killing compared with LVS (Fig. 3A). Because H2O2 is the principle mediator of ROS-dependent signaling, we next determined whether enhanced resistance of SchuS4 to H2O2 might be responsible for its ability to efficiently restrict host cell signaling. H2O2 reversibly oxidizes many protein-tyrosine phosphatases, including PTEN, because of the lowered pKa of their active-site cysteine (9, 10, 23). The reduced and oxidized forms of PTEN can be visualized on native nonreducing gels, as they migrate distinctly (11). Addition of 300 μm H2O2 to uninfected HT1080 cells led to complete oxidation of PTEN that was partially blocked by infection with wild-type LVS but not by the catalase gene deletion mutant of LVS (ΔkatG) (Fig. 3, B and C). Equivalent infection with SchuS4 blocked H2O2-dependent PTEN oxidation. Concomitant with the oxidation of PTEN was an increase in Akt phosphorylation in both the uninfected control and ΔkatG-infected cells but not in the LVS- and SchuS4-infected cells (Fig. 3B). Bolus addition of H2O2 (3 mm) led to complete PTEN oxidation upon infection with either SchuS4 or LVS (Fig. 3B, lower panel). hMDMs were also susceptible to H2O2-dependent PTEN oxidation. LVS infection partially restricted PTEN oxidation compared with ΔkatG infection, whereas no overt differences were observed in phospho-Akt levels. In contrast, H2O2-dependent PTEN oxidation and Akt phosphorylation were completely blocked upon infection of hMDMs with SchuS4 (Fig. 3D). These results corroborate the lower levels of phospho-PTEN and phospho-Akt levels observed in SchuS4-infected cells (Fig. 2F), where the samples were run under reducing conditions and the oxidation state of PTEN was not determined. Collectively, these data provide evidence that the activity of Akt is redox-regulated through its redox-sensitive antagonist PTEN and demonstrate that the potent antioxidant defenses of F. tularensis SchuS4 preserve PTEN in its reduced form to suppress downstream activation of Akt.

FIGURE 3.

F. tularensis modulates PTEN oxidation and Akt phosphorylation. A, A600 of F. tularensis LVS and SchuS4 following 18 h of treatment with the indicated concentrations of H2O2. Data represent the mean ± S.E. of quadruplicate samples. PI, post-infection. B, infection of HT1080 cells with LVS, ΔkatG, or SchuS4 for 1 h. 300 μm H2O2 was added (3 mm H2O2 was added in the lower panel). PTEN oxidation and Akt phosphorylation were determined by Western blot analysis. Uninf., uninfected. C, densitometric analysis of reduced (re) and oxidized (ox) PTEN expressed as percent of total PTEN (n = 3). D, Western blot analysis of PTEN oxidation and Akt phosphorylation in hMDMs infected with LVS (L), ΔkatG (K), or SchuS4 (S) for 1 h and treated with 300 μm H2O2. Statistical analyses were performed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test, and p values were recorded. *, p < 0.05. U, uninfected; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

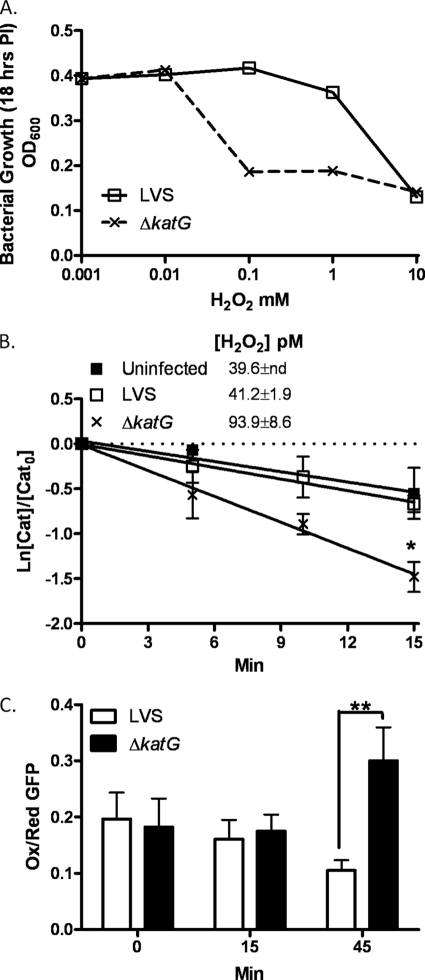

Loss of F. tularensis Catalase Enhances Steady-state H2O2 Concentrations Because of Its Deficiency in Detoxifying H2O2 from Infected Macrophages

We next confirmed whether the impaired capacity of ΔkatG to restrict host cell signaling is associated with its increased sensitivity to H2O2. As reported previously (9, 27), ΔkatG is quite sensitive to H2O2 compared with LVS (Fig. 4A) (13). We further monitored whether infection with ΔkatG mutant impacts the host production of oxidants. A direct estimate of steady-state H2O2 concentrations was calculated using the biochemical approach reported earlier (17). Infection of hMDMs with ΔkatG indicated a robust increase in the H2O2 concentration (93.9 pm) relative to LVS (41.2 pm) (Fig. 4B). The measurements were made 30 min post-infection, when the contribution of bacterial catalase to the monitoring system is minute (4.3 × 10−5 units/mg). An increase in the H2O2 concentration in macrophages infected with the ΔkatG mutant may be attributed to a decline in the antioxidant status of the bacteria because of loss of KatG with no apparent increase in oxidant flux. This work did not address this possibility. It is notable that no changes in H2O2 levels in LVS-infected and uninfected cells were observed. However, our results suggest that a decline in the antioxidant status of Francisella may be a significant contributing factor to the apparent increase in oxidative stress in infected macrophages.

FIGURE 4.

F. tularensis catalase protects from H2O2 toxicity and restricts macrophage H2O2 production. A, shown are A600 measurements of F. tularensis LVS and ΔkatG following 22 h of treatment with the indicated concentrations of H2O2. PI, post-infection. B, intracellular H2O2 levels were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data points were normalized by dividing with catalase (Cat) activity measured at time 0. The data represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. C, U937 cells transfected with roGFP1 were infected with LVS or ΔkatG. GFP fluorescence resulting from excitation at either 400 or 470 nm was monitored at the indicated times. The results are expressed as relative to the ratios of the 400/470 nm spectra. Increases in the 400/470 nm ratio are indicative of greater oxidation. The statistical significance of the results was examined by Student's t test, and p values were recorded. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with infection with LVS. Ox, oxidized; Red, reduced.

To further evaluate the redox state of F. tularensis-infected macrophages, we transiently transfected the U937 macrophage cell line with a redox-sensing GFP construct (roGFP1) (18). roGFP1 contains two redox-sensitive cysteines that form a disulfide bridge in response to oxidation. By modulating the excitation spectra of GFP and in combination with ratiometric fluorescence microscopy, oxidant production was monitored in real time in LVS- and ΔkatG-infected cells. The cells infected with ΔkatG showed a significantly higher proportion of oxidized to reduced roGFP1 relative to the cells infected with LVS (Fig. 4C). The difference in roGFP1 oxidation was observed 45 min post-infection and correlated well with the increase in the steady-state production of H2O2 shown in Fig. 4B. These observations suggest that F. tularensis catalase not only protects from H2O2 toxicity but also tempers the oxidizing potential of the host cells.

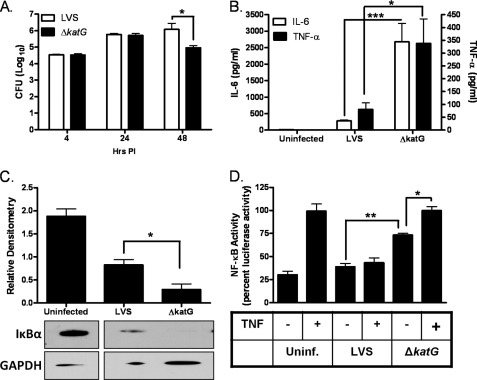

Infection of hMDMs with Catalase-deficient F. tularensis Markedly Augments Cytokine Production and NF-κB Signaling

We next determined whether loss of catalase impacts intracellular survival and proinflammatory cytokine stimulatory capacity. Both LVS- and ΔkatG-infected unstimulated hMDMs equally well at 4 h and replicated at similar rates 24 h post-infection (Fig. 5A). However, later in infection, ΔkatG displayed a significant decrease in its infective capacity relative to LVS. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were also increased post-infection with ΔkatG relative to LVS (Fig. 5B). The enhanced capacity of ΔkatG to stimulate proinflammatory cytokine production from infected macrophages was also associated with a rapid loss of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB compared with LVS infection (Fig. 5C). The ability of ΔkatG to modulate NF-κB promoter activity was also monitored. Correspondingly, cells infected with ΔkatG displayed a more pronounced increase in NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, TNF-α-dependent activation of the NF-κB promoter was suppressed by infection with LVS but not ΔkatG (Fig. 5D). These results demonstrate that F. tularensis catalase tempers proinflammatory cytokine production by suppressing NF-κB activation in infected hMDMs.

FIGURE 5.

Loss of F. tularensis catalase impairs the cytokine-suppressing capacity of F. tularensis. Unstimulated hMDMs were infected with LVS or ΔkatG. A, the cells were lysed at 24 h post-infection (PI), and intracellular bacteria were quantified. CFU, colony-forming units. B, IL-6 and TNF-α levels were measured in cell culture supernatants (n = 6) 24 h post-infection using the BDTM cytometric bead array. C, hMDMs were infected with LVS or ΔkatG for 20 min. IκBα degradation was determined by Western blot analysis. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. D, shown is the luciferase activity in HT1080 cells transfected with the NF-κB-luciferase construct and infected with LVS or ΔkatG for 4 h. TNF-α (10 ng) was added after 2 h of infection where indicated. The data are expressed as percent luciferase activity and represent the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. The statistical significance of the results was examined with the Student's t test, and p values were recorded. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with infection with LVS. Uninf., uninfected.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial antioxidants serve to combat the production of microbicidal host-derived and environmental oxidants. Francisella subspecies encode a full repertoire of antioxidant enzymes, including iron- and copper/zinc-containing superoxide dismutases (SodB and SodC, respectively), catalase (KatG), and alkylhydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) homologs. Mutants of Francisella deficient in these primary antioxidant defenses are sensitive to oxidative stress, defective for intramacrophage growth, and attenuated for virulence in mice (13, 14, 24). Recently, Wehrly et al. (25) reported an increase in the transcriptional levels of F. tularensis antioxidants following infection of macrophages as early as 1 h post-infection, suggesting a significant role of these antioxidant defenses in intramacrophage survival. Culture conditions that mimic intracellular macrophage growth enhance F. tularensis KatG expression and limit its capacity to stimulate macrophage cytokine production (26). It has been reported that redox-dependent inactivation of signaling components plays an important role in long-term homeostasis of human alveolar macrophages (27). F. tularensis encounters these cells immediately following pulmonary infection, replicates, and is rapidly disseminated to liver and spleen (28, 29). F. tularensis also survives in macrophages and dendritic cells by suppressing activation of proinflammatory cytokines (6, 7, 30, 31). Thus, modulation of macrophage function by F. tularensis offers a mechanism through which these virulent bacteria suppress the innate immune response for survival. However, Francisella factors and mechanisms responsible for mediating these immune subversive effects are not completely understood. The findings from this study now demonstrate that antioxidants of Francisella harness ROS to limit activation of redox signals that drive innate immune activation.

There is evidence that LVS has the ability to inhibit cytokine production by impairing the host response to Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists and TNF-α (32). We studied the effect on TNF-α-mediated translocation of p65 in IFN-γ-activated macrophages infected with LVS and SchuS4. Our results show that LVS only partially restricts TNF-α-dependent p65 nuclear translocation, which is in contrast to the nearly complete inhibition observed in IFN-γ-primed macrophages infected with SchuS4 (Fig. 2, C and D). These results indicate that F. tularensis interferes with the canonical NF-κB pathway activated by TNF-α. The inhibition of TNF-α-dependent translocation of p65 by F. tularensis LVS or SchuS4 has not been explored previously in IFN-γ-activated macrophages. However, it has been shown that a cooperative relationship exists between TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation and IFN-γ priming of cells (33). Similarly, a synergy has been shown to exist at multiple levels between IFN-γ priming and the TLR signaling pathways (34). Additionally, it has been established that macrophage-derived oxidants, particularly H2O2, activate NF-κB and AP-1 via TLR2 (35). Our observation that LVS is not as efficient at scavenging H2O2 or preventing oxidation of PTEN (Fig. 3) supports the findings associated with partial TNF-α-dependent nuclear localization of p65 in LVS- compared with SchuS4-infected macrophages. Furthermore, the ability of SchuS4 to suppress TLR2-dependent NF-κB signaling coupled with its robust oxidant-scavenging potential suggests that its antioxidant defenses may also interfere with TLR2 signaling in addition to the canonical NF-κB pathway. Further studies are required to address the role of oxidant-induced TLR signaling in response to infection with LVS and SchuS4 mutants lacking oxidant-scavenging ability.

Macrophage activation is controlled by a diverse set of signals that are amenable to redox regulation. The activity of Akt, which restricts F. tularensis virulence, is redox-regulated through its redox-sensitive antagonist PTEN. H2O2 is the principle mediator of ROS-dependent signaling, which is produced in response to numerous stimuli. The essential cysteine residue in the protein-tyrosine phosphatases including the PTEN signature active-site motif Cys-X5-Arg, exists as a thiolate anion (Cys-S−), which, at neutral pH, is susceptible to nucleophilic attack by H2O2. Oxidation of the active-site cysteine generates a sulfenic derivative (Cys-SOH), leading to enzyme inactivation that can be reversed by cellular thiols (10). Our findings support the hypothesis that the potent antioxidant defenses of F. tularensis preserve PTEN and thereby suppress downstream activation of Akt and NF-κB. Additionally, we have identified F. tularensis catalase as an important mediator in restricting H2O2-dependent PTEN oxidation. SchuS4 is capable of effectively blocking PTEN oxidation, which is likely linked to its extreme resistance to oxidative stress. PTEN contains two oxidant-sensitive cysteines that must be reduced by thioredoxin NADP(H) disulfide reduction to maintain phosphatase activity (36). Depletion of both cellular peroxidases and thioredoxin-interacting protein enhances PTEN oxidation (37, 38). Our findings indicate that infection of macrophages with catalase-deficient bacteria shifts their redox state toward a more oxidizing environment. Infection with antioxidant-rich bacteria may serve to preserve intracellular thiol and NADPH pools, limit oxidation, and maintain PTEN in its reduced active conformation.

Recent evidence has shown that preservation of PTEN activity decreases the pool of phosphoinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate available at the membrane (39). Limiting the amount of phosphoinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate at the membrane directly decreases Akt activation. Akt plays a prominent role in regulating cytokine production and susceptibility to Francisella infection (4, 7). Akt regulates NF-κB activity by IκK activation, which in turn phosphorylates the inhibitory subunit of the NF-κB complex, IκB, leading to its ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Release of NF-κB allows for its nuclear recruitment, which ultimately drives the expression of a diverse array of inflammatory cytokine genes. SchuS4 infection preserves IκB by restricting its decay and delaying or inhibiting the activation of NF-κB-responsive genes. Differences in the kinetics of IκB degradation and phosphorylation between Francisella subspecies suggest that SchuS4 displays a more prolonged delay in activating NF-κB. These differences may in fact account for the differences in virulence of these two Francisella strains in both mice and humans. Combined, these studies suggest that F. tularensis actively suppresses cytokine production by restricting NF-κB activation. This delay or inhibition of NF-κB activation by F. tularensis may also explain its ability to suppress LPS-dependent cytokine production, as reported by Butchar et al. (6).

To conclude, this study highlights a previously underappreciated role for bacterial antioxidants in the control of macrophage function. Survival inside macrophages is an essential first step in the establishment of infection by F. tularensis. Our findings demonstrate that unusually high resistance of F. tularensis to oxidative stress plays an essential dual role in its intramacrophage survival. The Francisella antioxidant armature not only renders resistance to H2O2 toxicity but also alters redox-sensitive signaling components to subvert the development of an effective innate immune response. Overall, this study provides mechanistic evidence as to how F. tularensis and potentially other bacterial pathogens utilize their robust antioxidant defenses to modulate redox-dependent host cell signaling to suppress host microbicidal effector responses.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Carl Zingmark and Anders Sjöstedt (University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden) for providing the ΔkatG mutant of F. tularensis LVS. We also thank Erin Moore, Bryan Abessi, and Michelle Wyland for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 2P01AI056320.

- LVS

- live vaccine strain

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- hMDM

- human monocyte-derived macrophage

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oyston P. C., Sjostedt A., Titball R. W. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 967–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telepnev M., Golovliov I., Sjöstedt A. (2005) Microb. Pathog. 38, 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauriano C. M., Barker J. R., Yoon S. S., Nano F. E., Arulanandam B. P., Hassett D. J., Klose K. E. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4246–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajaram M. V., Ganesan L. P., Parsa K. V., Butchar J. P., Gunn J. S., Tridandapani S. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 6317–6324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsa K. V., Ganesan L. P., Rajaram M. V., Gavrilin M. A., Balagopal A., Mohapatra N. P., Wewers M. D., Schlesinger L. S., Gunn J. S., Tridandapani S. (2006) PLoS Pathog. 2, e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butchar J. P., Cremer T. J., Clay C. D., Gavrilin M. A., Wewers M. D., Marsh C. B., Schlesinger L. S., Tridandapani S. (2008) PLoS ONE 3, e2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cremer T. J., Ravneberg D. H., Clay C. D., Piper-Hunter M. G., Marsh C. B., Elton T. S., Gunn J. S., Amer A., Kanneganti T. D., Schlesinger L. S., Butchar J. P., Tridandapani S. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e8508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hrstka R., Krocova Z., Cerny J., Vojtesek B., Macela A., Stulik J. (2007) Folia Microbiol. 52, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie N. R., Bennett D., Lindsay Y. E., Stewart H., Gray A., Downes C. P. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5501–5510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarugi P., Fiaschi T., Taddei M. L., Talini D., Giannoni E., Raugei G., Ramponi G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33478–33487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S. R., Yang K. S., Kwon J., Lee C., Jeong W., Rhee S. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20336–20342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantano C., Reynaert N. L., van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1791–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindgren H., Shen H., Zingmark C., Golovliov I., Conlan W., Sjöstedt A. (2007) Infect. Immun. 75, 1303–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melillo A. A., Mahawar M., Sellati T. J., Malik M., Metzger D. W., Melendez J. A., Bakshi C. S. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 6447–6456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedoya F., Sandler L. L., Harton J. A. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 3837–3845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claiborne A. (1985) in CRC Handbook of Methods for Oxygen Radical Research (Greenwald R. A. ed), pp. 283–289, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta J., Subbaram S., Connor K. M., Rodriguez A. M., Tirosh O., Beckman J. S., Jourd'Heuil D., Melendez J. A. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1295–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooley C. T., Dore T. M., Hanson G. T., Jackson W. C., Remington S. J., Tsien R. Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22284–22293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anthony L. S., Ghadirian E., Nestel F. P., Kongshavn P. A. (1989) Microb. Pathog. 7, 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiby D. A., Fortier A. H., Crawford R. M., Schreiber R. D., Nacy C. A. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60, 84–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothwarf D. M., Karin M. (1999) Sci. STKE 1999, RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S., Domon-Dell C., Kang J., Chung D. H., Freund J. N., Evers B. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4285–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng T. C., Fukada T., Tonks N. K. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakshi C. S., Malik M., Regan K., Melendez J. A., Metzger D. W., Pavlov V. M., Sellati T. J. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188, 6443–6448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wehrly T. D., Chong A., Virtaneva K., Sturdevant D. E., Child R., Edwards J. A., Brouwer D., Nair V., Fischer E. R., Wicke L., Curda A. J., Kupko J. J., 3rd, Martens C., Crane D. D., Bosio C. M., Porcella S. F., Celli J. (2009) Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1128–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazlett K. R., Caldon S. D., McArthur D. G., Cirillo K. A., Kirimanjeswara G. S., Magguilli M. L., Malik M., Shah A., Broderick S., Golovliov I., Metzger D. W., Rajan K., Sellati T. J., Loegering D. J. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 4479–4488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flaherty D. M., Monick M. M., Hinde S. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5058–5064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ojeda S. S., Wang Z. J., Mares C. A., Chang T. A., Li Q., Morris E. G., Jerabek P. A., Teale J. M. (2008) BMC Microbiol. 8, 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meibom K. L., Barel M., Charbit A. (2009) Future Microbiol. 4, 713–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chase J. C., Celli J., Bosio C. M. (2009) Infect. Immun. 77, 180–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosio C. M., Bielefeldt-Ohmann H., Belisle J. T. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 4538–4547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosio C. M., Dow S. W. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 6792–6801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganster R. W., Guo Z., Shao L., Geller D. A. (2005) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25, 707–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroder K., Sweet M. J., Hume D. A. (2006) Immunobiology 211, 511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frantz S., Kelly R. A., Bourcier T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5197–5203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwon J., Lee S. R., Yang K. S., Ahn Y., Kim Y. J., Stadtman E. R., Rhee S. G. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16419–16424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao J., Schulte J., Knight A., Leslie N. R., Zagozdzon A., Bronson R., Manevich Y., Beeson C., Neumann C. A. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 1505–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hui S. T., Andres A. M., Miller A. K., Spann N. J., Potter D. W., Post N. M., Chen A. Z., Sachithanantham S., Jung D. Y., Kim J. K., Davis R. A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3921–3926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim J. H., Lee G., Cho Y. L., Kim C. K., Han S., Lee H., Choi J. S., Choe J., Won M. H., Kwon Y. G., Ha K. S., Kim Y. M. (2009) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 602, 422–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]