Abstract

The 3C-like proteinase (3CLpro) of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus plays a vital role in virus maturation and is proposed to be a key target for drug design against SARS. Various in vitro studies revealed that only the dimer of the matured 3CLpro is active. However, as the internally encoded 3CLpro gets matured from the replicase polyprotein by autolytic cleavage at both the N-terminal and the C-terminal flanking sites, it is unclear whether the polyprotein also needs to dimerize first for its autocleavage reaction. We constructed a large protein containing the cyan fluorescent protein (C), the N-terminal flanking substrate peptide of SARS 3CLpro (XX), SARS 3CLpro (3CLP), and the yellow fluorescent protein (Y) to study the autoprocessing of 3CLpro using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. In contrast to the matured 3CLpro, the polyprotein, as well as the one-step digested product, 3CLP-Y-His, were shown to be monomeric in gel filtration and analytic ultracentrifuge analysis. However, dimers can still be induced and detected when incubating these large proteins with a substrate analog compound in both chemical cross-linking experiments and analytic ultracentrifuge analysis. We also measured enzyme activity under different enzyme concentrations and found a clear tendency of substrate-induced dimer formation. Based on these discoveries, we conclude that substrate-induced dimerization is essential for the activity of SARS-3CLpro in the polyprotein, and a modified model for the 3CLpro maturation process was proposed. As many viral proteases undergo a similar maturation process, this model might be generally applicable.

Keywords: Enzyme Mechanisms, Serine Protease, Viral Protease, Viral Protein, Viral Replication, 3C-like Proteinase, SARS-CoV, Dynamic Control, Maturation Mechanism

Introduction

Shortly after its outbreak in 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)2 was confirmed to be caused by a new type of coronavirus, SARS-CoV. Similar to other coronaviruses, two-thirds of its genome encodes two large replicase polyproteins, pp 1a (450 kDa) and pp lab (750 kDa), which will undergo extensive proteolytic processing mainly by the internally encoded main proteinase (also called 3C-like proteinase, 3CLpro) to produce multiple functional subunits that mediate both genome replication and transcription (1).

The crystal structure of SARS wild type 3CLpro is a homodimer (Protein Data Bank codes 1Q2W, 1UJ1, and 1UK2) and topologically similar to the other coronaviruses such as transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E (2, 3) (Protein Data Bank codes 1LVO and 1P9U). One protomer of 3CLpro consists of three domains, of which the first two form a chymotrypsin fold, and is connected by a long loop with the third extra helix domain. The catalytic dyad, His-41 and Cys-145, locates in the deep cleft between domain I and II. We have shown that the dimer is the biologically functional form of matured 3CLpro (4), and only one monomer is active (5). Certain single site mutations, such as M6A, G11A, S39A, and R298A, result in inactive monomers (6–9).

Dimerization is a commonly used strategy in viral protease activity regulation (10). Many of the reported viral proteases are active only in dimer form (4, 11–14). For enzymes with an active site formed by residues from both the protomers, like HIV-1 protease (15), it is straightforward to understand why the dimer formation is necessary. However, for proteases with a complete active site in one protomer, dimerization may be one method to regulate its activity. It is interesting to know what happens for these proteases before they have been cleaved out from the polyprotein as it might be difficult for a large flexible polyprotein to form a stable dimer. A recent study revealed that the mini-precursor of HIV-1 protease formed a highly transient but low populated dimeric structure during maturation (16).

For SARS 3CLpro, much has been learned about its catalytic mechanism (17), substrate specificity (18), as well as inhibitor design (19, 20). However, few studies have been reported on its maturation mechanism. Shan et al. (21) introduced a 31-mer peptide containing an autocleavage site flanking to the N terminus of 3CLpro to test the in cis activity of SARS 3CLpro. They found that the peptide can be autocleaved efficiently by 3CLpro itself by monitoring the autocleavage products on the gel. Hsu et al. (22) reported that the SARS 3CLpro can be matured from polyprotein with flanking N- and C-terminal segments in vitro. The N terminus is digested faster than the C terminus, and during digestion, the 3CLpro with 10 residues attached to both the N terminus and the C terminus can form dimer. However, 10 residues flanking at the N terminus and C terminus might be too short and may not reflect the real situation in the polyprotein. To understand the maturation and activity regulation mechanism of SARS 3CLpro, we constructed an artificial polyprotein containing cyan fluorescent protein (C), the N-terminal natural flanking substrate peptide of SARS 3CLpro, SITSAVLQ (XX), SARS 3CLpro (3CLP), and yellow fluorescent protein (Y) and used it to study the autoprocessing mechanism of SARS 3CLpro polyprotein. In contrast to the dimerization of the matured enzyme, this polyprotein and its N-terminal cleaved product were found to be monomeric in conventional analysis but are still active.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction of the Large Fusion Proteins His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, His-C-XX-C145A-Y, 3CLP-Y-His, and 3CLP- MBP-His

The large fusion protein constructs basically contained four components in sequence. The first component is C, and the second component is XX, which is the natural autocleavage substrate peptide of SARS-CoV 3CLpro derived from the natural pp1a/pp1ab polyprotein attached to its N terminus. Sequence analysis revealed 11 cleavage sites of SARS 3CLpro on the SARS polyproteins, all of which contain a highly conserved substrate sequence (P1 Gln↓P1′ Ser/Ala) (23). The N-terminal autolytic substrate peptide (SITSAVLQ↓SGF) has the highest cleavage efficiency among all 11 substrate peptides (4). The third component consists of 3CLP or mutants, and the fourth component is Y, so the construct is named C-XX-3CLP-Y.

To prepare His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y, a cloning vector pET28a-CY2.0 with His6 tag at the N terminus was built first (supplemental Fig. S1). Detailed experimental procedures can be found in the supplemental material. Here, Q/E represents the mutation of Gln in the extra 8-amino acid peptide (SITSAVLQ) to Glu. Mutation of the critical residue Gln at the P1 position to Glu completely abolishes the hydrolytic activity of SARS 3CLpro (18).

3CLP-Y-His is the truncated protein of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, which also had a His6 tag at the C terminus for further protein purification (supplemental Fig. S1). 3CLP-MBP-His was a plasmid in which the YFP of 3CLP-Y-His was replaced by maltose-binding protein (MBP) (supplemental Fig. S1).

All the plasmids were constructed following the methods listed in the supplemental material, and primers needed were listed in supplemental Table S1. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Invitrogen).

Fusion Protein Expression and Purification

The large polyproteins with His6 tags were expressed and purified with a slightly modified procedure when compared with the matured enzyme (4) (see detailed information in supplemental material). The method for wild type SARS-CoV 3CL proteinase expression and purification was the same as reported before (17).

Analytic Gel Filtration Analysis

The aggregation state of the large fusion proteins, His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y, and the truncated one, 3CLP-Y-His, were analyzed using a Superdex 200 HR 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) on ÄKTA fast protein liquid chromatography. The purified proteins, at different concentrations, were loaded on the column, which was pre-equilibrated to 36 ml of buffer A (40 mm phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.3, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA). The column was eluted with another 36 ml of buffer A at flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, during which the eluted volume of the fraction peak at 280 nm was monitored on fast protein liquid chromatography. The concentrations loaded onto the column were: 1) His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, 4.4 and 10 mg/ml; 2) His-C-XX-C145A-Y, 4.4 and 10 mg/ml; and 3) 3CLP-Y-His, 6 mg/ml. Gel filtration molecular weight markers used and the standard calibration curve can be found in supplemental Table S2 and supplemental Fig. S3.

Analytic Ultracentrifugation (AUC) Analysis

Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out using a Beckman Optima XLA analytical ultracentrifuge. The procedure of sedimentation velocity was the same as reported previously (6). His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, His-C-XX-C145A-Y, and 3CLP-Y-His were prepared in buffer A. Samples (1 mg/ml, 380 μl) and reference (400 μl) were loaded into double-sector centerpieces. Data were analyzed with Sedfit version 11.71.

In Vitro Trans-cleavage Activity Assay

7.5 μm His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y (or 3CLP-Y-His or 3CLP-MBP-His) as the enzyme and 22.5 μm His-C-XX-C145A-Y as the substrate were mixed and incubated in buffer A with 5 mm dithiothreitol at 37 °C with 500 rpm of shaking for 2 h. The substrate His-C-XX-C145A-Y was cleaved at the substrate peptide Q↓S bond to release two fragments, which eliminated FRET and resulted in a decrease at 527 nm. To confirm the molecular weight of the two products, sample aliquots of 10 μl were taken out at different reaction times. For enzyme His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, samples were taken out at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min and put on ice. In addition, for 3CLP-Y-His, samples were taken out at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min. One part of the reaction mixture (5 μl) was diluted 40 times into ice-cold buffer A for FRET, and the other 5 μl was mixed with 5 μl of 2× SDS-loading buffer for SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gel. Control assays were also performed by incubating 7.5 μm His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y (or 3CLP-Y-His) and 22.5 μm His-C-XX-C145A-Y alone at the same conditions as the first test described above.

Kinetic Measurement of Enzyme Activity

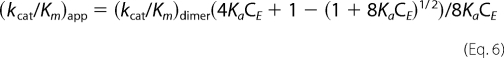

A colorimetric substrate, Thr-Ser-Ala-Val-Leu-Gln-pNA (GL Biochemistry Ltd.), was used for enzyme concentration-dependent kinetic measurement (17). The substrate was cleaved at the Gln-pNA bond to release free pNA, resulting in an increase of absorbance at 390 nm (measured using SynergyTM4, BIOTEK). Enzyme concentration ranges used here were 2.25–45 μm for His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, 1.36–21.78 μm for 3CLP-Y-His, and 0.225–4.5 μm for SARS-3CLpro in a 100-μl volume, respectively. The enzyme concentration dependence of rate constants was measured at 37 °C in buffer A with 5 mm dithiothreitol. The apparent second-order rate constant kcat/Km was calculated by dividing the pseudo-first-order constant by the enzyme concentration (17, 24). We have derived a fitting model to obtain intrinsic kcat/Km (24). To be brief, the apparent enzyme activity was contributed from the dimers as well as the monomers in solution.

|

in which (kcat/Km)app is the apparent second-order rate constant, (kcat/Km)mono and (kcat/Km)dimer are that of the monomer and dimers, and CE is the total enzyme concentration. Cmono and Cdimer are the concentration of monomer and dimer, respectively.

As the monomers can associate into dimers, we get

thus

in which M is monomer, M2 is dimer, and Ka is the monomer-dimer association constant.

We have tried to fit Equation 1 and found that the activities of monomers were negligible for the matured 3CLpro, as well as the polyproteins. This confirmed again that dimer is the active form. We then omitted the contribution from the monomers and fitted the data using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab) according to the following equation (24).

|

The kcat/Km of dimer and its association constant can be obtained from the fitting.

Inhibition Efficiency of the Isatin Compound 5f on His-Y- XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y

A known inhibitor, the isatin derivative, 1-(2-naphthlmethyl) isatin-5-carboxamide (5f) (25), was dissolved in DMSO to test the inhibition efficiency toward the polyprotein. To reduce the high background of FRET, another large fusion protein plasmid, His-Y-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, was prepared as above, replacing the first cyan fluorescent protein by YFP, which was used as the enzyme for the inhibition test. 7.5 μm His-Y-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and 50 μm 5f (control was 5% DMSO) were preincubated in buffer A at 37 °C for 15 min, and then 22.5 μm His-C-XX-C145A-Y (substrate) was added to the mixture to react for 2 h. Samples were taken at different reaction times for FRET measurement.

Chemical Cross-linking

Enzymes (6 mg/ml His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, 6 mg/ml 3CLP-Y-His, and 5.12 mg/ml SARS-3CLpro) alone or mixed with equal molar 5f were cross-linked by 10-fold molar excess ethylene glycol bis (succinimidyl succinate) in buffer A at room temperature for 30 min and then quenched by adding Tris (1 m, pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 50 mm.

RESULTS

Aggregation State of the Free Polyproteins

We investigated the aggregation states of the fusion proteins using gel filtration and analytic ultracentrifugation to see whether they can still form dimers in solution. To avoid autocleavage, two mutants, His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y, were used for aggregation studies. The Gln to Glu mutation makes the substrate sequence XX uncleavable, whereas the Cys-145 to Ala mutation results an inactive enzyme.

Analytic Gel Filtration Analysis

Both His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y showed high FRET efficiency (supplemental Fig. S2), indicating that they were intact. A Superdex 200 HR 10/300 GL column was used to estimate their apparent molecular weights based on the retention volume at different protein concentrations (see details in the supplemental material). Both proteins were shown to be monomeric even at high concentration of 10 mg/ml (supplemental Table S3 and supplemental Fig. S3).

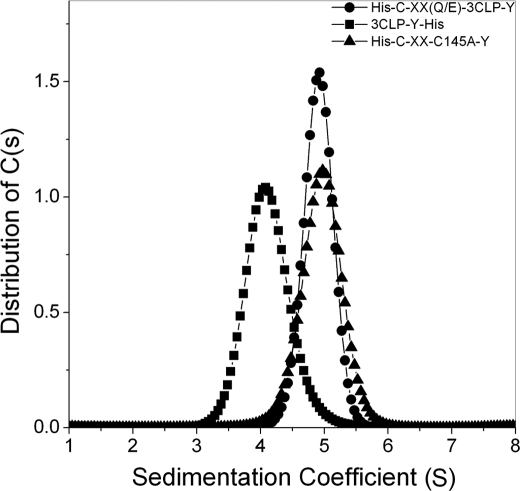

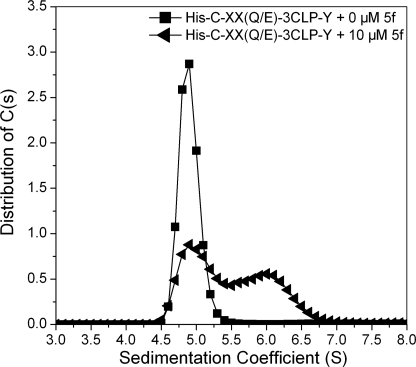

Analytic Ultracentrifugation Analysis

To further verify the aggregation state of the polyproteins, sedimentation velocity experiments were performed. The sedimentation experiments provide hydrodynamic information about the molecular size distribution and conformational changes in the native solution with no dilution effect when compared with gel filtration. Sedimentation velocity was used to determine the sedimentation coefficient distribution c(s) and the molecular weight distribution c(M) of polyproteins at 1 mg/ml. The resulting c(s) and c(M) distribution profiles showed that only one peak was detected (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S4). Sedimentation coefficients of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y were ∼4.9 and ∼5.0 S, respectively. Based on the c(M) distribution model, the molecular masses of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y were estimated to be 82.7 and 86.0 kDa (supplemental Table S4), indicating that both of them were monomeric.

FIGURE 1.

Sedimentation coefficient distribution c(s) profile of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y, His-C-XX-C145A-Y, and 3CLP-Y-His at 40,000 rpm and 20 °C.

In Vitro Trans-cleavage Activity Assay of 3CLpro in Polyprotein

The fusion polyproteins containing SARS 3CLpro were shown to be monomeric in solution. To test its activity, trans-cleavage was monitored in vitro by FRET signal and confirmed through SDS-PAGE.

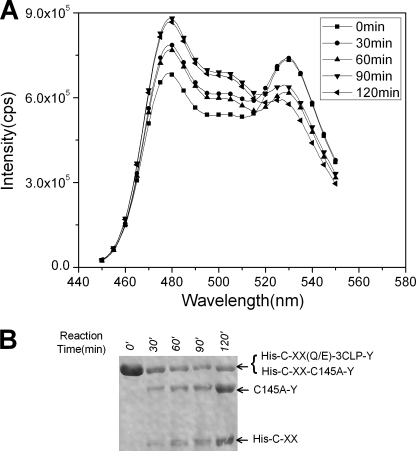

His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y was used as the enzyme, and His-C-XX-C145A-Y was used as the substrate. Two control experiments were also carried out by incubating His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y for 120 min, and the fluorescence spectra did not change. At the beginning of the reaction, a high efficiency FRET signal was detected, which decreased along with the digestion (Fig. 2), indicating that His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y digested the substrate His-C-XX-C145A-Y well. Further supporting evidence was obtained from SDS-PAGE. In the beginning, only one band at 91 kDa was observed. After incubation for some time, the 91-kDa band became weaker. At the same time, two lower molecular mass bands appeared and turned thicker, indicating that His-C-XX-C145A-Y was digested into two parts (about 27 and 64 kDa). The monomeric polyprotein can still retain its enzymatic activity in vitro.

FIGURE 2.

The enzymatic activity of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y in vitro. A, FRET spectra at different reaction times. B, SDS-PAGE for the digestion at different times. From lanes 1-5, samples from 0-, 30-, 60-, 90-, and 120-min reaction times were loaded, respectively. The bands from top to bottom show the mixture of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y and His-C-XX-C145A-Y, the cleavage product I C145A-Y, and the cleavage product II His-C-XX.

Properties of the Truncated Fusion Protein 3CLP-Y-His

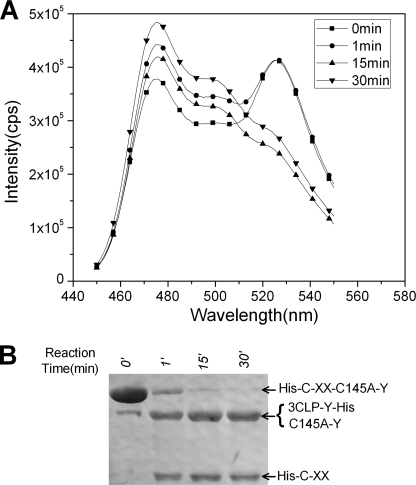

The results shown above indicate that the 3CLpro in the polyprotein appeared to be monomeric and was enzymatically active. We then wanted to know the property and activity of the N-terminal cleaved polyprotein. A truncated protein, 3CLP-Y-His, containing the 3CLpro, the YFP protein, and a C-terminal His tag, was expressed and purified in vitro. The enzymatic activity was tested using His-C-XX-C145A-Y as substrate. 3CLP-Y-His digested the substrate His-C-XX-C145A-Y very rapidly. Within 15 min, almost 95% of the substrate was digested (Fig. 3), which is much faster than the full polyprotein (Fig. 2). Gel filtration and analytic ultracentrifugation analysis showed that 3CLP-Y-His was also monomeric (Fig. 1, supplemental Figs. S3 and S4, and supplemental Tables S3 and S4).

FIGURE 3.

The enzymatic activity of 3CLP-Y-His in vitro. A, spectra of FRET monitoring of enzymatic activity of truncated fusion protein 3CLP-Y-His with different reaction times. B, samples from different reaction times were loaded onto SDS-PAGE. Lanes 1–4 show 0, 1, 15, and 30 min. The bands from top to bottom show His-C-XX-C145A-Y, a mixture of 3CLP-Y-His and cleavage products I C145A-Y, and cleavage product II His-C-XX.

To eliminate the possible effect of the YFP protein in 3CLP-Y-His, we substituted it with MBP protein to construct 3CLP-MBP-His, which showed almost the same activity as 3CLP-Y-His. We concluded that after the first step of autocleavage, the product containing a free N terminus and one protein attached to the C terminus remained monomeric in solution and with higher enzyme activity than the polyprotein with proteins attached to both ends. This enzyme activity was not related to the proteins attached to the 3CLP termini.

Inhibition Efficiency of an Isatin Inhibitor on His-Y- XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y

The isatin derivative 5f is a non-covalent SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease inhibitor, with an IC50 of 0.37 μm. We used 5f as a probe to test whether the substrate binding pocket conformation of 3CLpro in the polyprotein remains the same as that in the free 3CLpro. 5f can almost fully inhibit the enzymatic activity of His-Y-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y at 50 μm (supplemental Fig. S5 and supplemental Table S5), implying that the substrate binding pocket conformation of 3CLpro in the polyprotein is similar to that in the free 3CLpro.

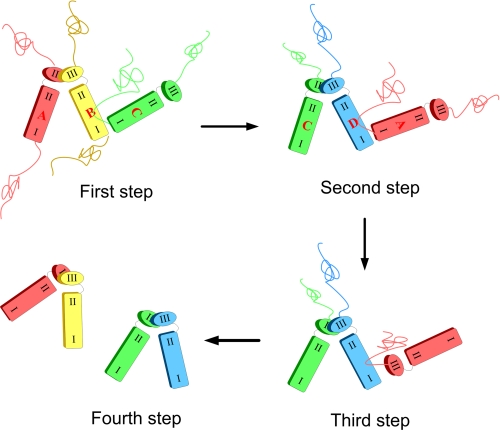

Aggregation State of the Polyproteins with the Presence of Substrate or Substrate Analog

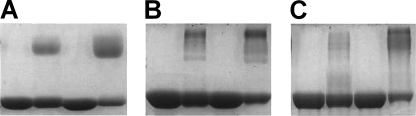

The experimental results above indicated that the polyproteins were monomeric in solution as free proteins. However, we still do not know whether they can form transient complexes in solution and what happens when they react with substrate. We did chemical cross-linking experiments for the two polyproteins without and with the presence of a substrate analog, an isatin derivative 5f. Similar to the substrate, 5f was shown to be able to enhance dimer formation for SARS-3CLpro in our previous study (24). From the cross-linking experiment, we can see that more dimers were formed for the wild type protein, the N-terminal cleaved protein, and the full-length large protein (Fig. 4). In fact, for the full-length large protein, the dimer band showed very weak, if any, formation, with EGS cross-linking in the absence of 5f, which turned out to be more obvious after cross-linking in the presence of 5f.

FIGURE 4.

SDS-PAGE of chemical cross-linking by EGS. A, wild type SARS-3CLpro (5.12 mg/ml). B, 3CLP-Y-His (6 mg/ml). C, His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y (6 mg/ml). For each PAGE, from left to right, lane 1 is the enzyme only, lane 2 is enzyme with EGS, lane 3 is enzyme with equal molar substrate analog 5f, and lane 4 is enzyme with equal molar substrate analog 5f and EGS.

Due to the experimental condition requirement for the cross-linking study, the protein concentration used is quite high. As such high concentration may not reflect the real situation in vivo, we then analyzed the aggregation state of the polyprotein His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y at a rational concentration (1 mg/ml) in the presence of 5f (25) at 10 μm using AUC. From the AUC results (Fig. 5), it is clear that the polyprotein is monomeric without 5f and partly forms dimer upon the addition of 5f. Thus with the presence of substrate, the polyproteins can also form dimers.

FIGURE 5.

Sedimentation coefficient distribution c(s) profile of His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y without and with the presence of isatin derivative 5f at 40,000 rpm and 20 °C.

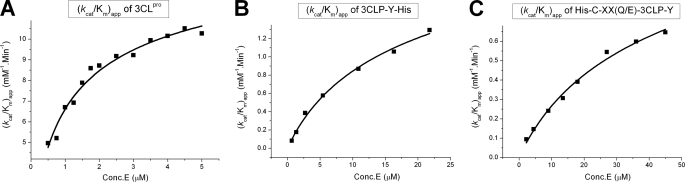

Dependence of Enzyme Activity on Enzyme Concentration

As shown in our previous studies (4, 24), the enzyme concentration dependence of SARS-3CLpro implies a dimer-only activity control mechanism. For the polyproteins, we also measured their apparent kcat/Km for pNA peptide substrate at different enzyme concentrations. The (kcat/Km)app increases along with the enzyme concentration increase in a similar way as the matured enzyme (Fig. 6). We also tested the concentration-dependent enzyme activity using the polyprotein His-C-XX-C145A-Y as substrate and observed a similar trend (data not shown). Together with the AUC analysis, we conclude that dimerization is also required for the polyprotein, although the dimer may only form transiently, which can be stabilized by substrate. We fitted the enzyme activity data using Equation 6 to derive (kcat/Km)dimer and association constant Ka (Table 1).

FIGURE 6.

Enzyme activity of SARS-3CLpro, 3CLP-YFP-His, and His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y at different concentrations. The apparent velocity second-order constant (kcat/Km)app increases in the same manner as matured SARS-3CLpro as the enzyme concentration (Conc E) increases, indicating that the dimer form is the active form of the proteinase. ■, measured value of (kcat/Km)app; the solid line is the fitted curve.

TABLE 1.

Relative enzyme activities toward the pNA peptide substrate

The proteolysis activity of all the enzymes at different concentrations were determined by incubating 0.2 mm pNA peptide with the enzymes in buffer A (40 mm phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.3, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA) with 5 mm dithiothreitol.

| Enzyme | (kcat/Km)dimera | Kaa | Kdb |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm−1 · min−1 | μm−1 | μm | |

| His-C-XX(Q/E)-3CLP-Y | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 100 |

| 3CLP-Y-His | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 0.024 ± 0.004 | 42 |

| 3CLpro | 31.8 ± 1.2 | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 1.6 |

a Fitted and determined by Equation 6.

b Kd was derived from Ka.

From Table 1, we can see that among the three proteins containing 3CLpro, the intact polyprotein has the lowest ability to form active dimer, with a dimer (substrate-induced) dissociation constant of about 100 μm, whereas the N-terminal cleaved polyprotein has a somewhat stronger dimer formation ability (Kd around 42 μm) and the free protein has the strongest dimer formation ability (Kd around 1.6 μm). The catalytic activities of the dimers formed by the three proteins also follow the same order. As the apparent enzyme activity positively depends on the dimer activity and the dimer association constant, the intact polyprotein has quite low enzyme activity, and upon the first step of digestion, the activity of the truncated 3CLP-Y-His will be increased, and the matured 3CLpro will have the highest enzyme activity. Although different substrates may give different quantitative results, the activities should follow the same order.

DISCUSSION

Substrate-induced Dimerization Is Essential for the Activity of SARS-3CLpro in the Polyprotein

In vitro studies showed that dimerization is essential for the enzyme activity of SARS-3CLpro (4). However, whether dimerization is necessary for the activity of its precursor, the polyprotein, is still not clear. Hsu et al. (22) reported that the partially cleaved polyprotein can form a small amount of active dimer and proposed that during the autocleavage of the 3CLpro, the enzyme is dimeric at each step. However, in their study, only 10 residues were attached to both the termini of SARS-3CLpro, which may not be long enough to mimic the situation in the polyprotein as the hydrophobic regions 1 and 2 (HD1 and HD 2) attached to the N and C terminus of 3CLpro are more than 10 amino acids in the replicase of coronavirus (26).

In the current study, we used full-length folded proteins as an attachment to the two ends of 3CLpro to mimic the case in the replicase. Our results showed that 3CLpro in the polyprotein was monomeric in solution when standing alone, and the activity was not related to the proteins attached as the polyprotein kept its activity when substituting YFP with MBP. Furthermore, we also discovered that the N-terminal cleaved product of the polyprotein, which occurs when only one protein is attached to the C terminus of 3CLpro, was still active. These active polyproteins can also be deactivated by the previously reported 3CLpro inhibitor 5f, implying that the active site conformation in the polyprotein may be similar to that in the active protomer of the 3CLpro dimer.

Substrate-enhanced dimerization was observed for the matured SARS-3CLpro (24). The dissociation constant of pure SARS-3CLpro was measured to be 14 μm using sedimentation equilibrium. However, for most in vitro assays for SARS-3CLpro, the enzyme concentration was around 1 μm. As our previous study (4) and various other studies (19) have shown, only dimer is active for this enzyme. This brought a dilemma as the dimer concentration must be very low under the assay condition assuming a Kd of 14 μm. However, when substrate was present, the dimerization ability of SARS-3CLpro was significantly increased with a Kd around 1 μm under the experimental conditions (24).

For the case of the polyproteins, we also tested their enzyme activity change along with the increase of enzyme concentration. Similar to SARS-3CLpro, the apparent second-order constant, (kcat/Km)app, increases with the enzyme concentration (Fig. 6). Thus we postulated that the polyprotein also needs to dimerize first to perform its enzymatic function.

To verify this assumption, we also did EGS cross-linking and AUC analysis for the polyproteins with a substrate analog compound 5f. we found that significant dimer can be detected when both experiments were done in the presence of 5f. Thus we concluded that substrate-induced dimerization is essential for the activity of SARS-3CLpro in the polyprotein.

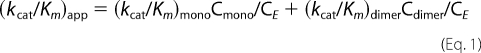

Possible Mechanism for the Cleavage Reaction of SARS-3CLpro in the Polyprotein

Although few autolytic studies have been reported for SARS 3CLpro, 3CLpro from other coronaviruses were studied in more detail. It was reported that the autoprocessing of 3CLpro was related to membrane (27–29), although the details of dynamic control during this process are still not clear. Our results indicate that although the polyprotein remains a monomer as free protein, it can form transient dimers upon substrate binding to perform their catalytic activity.

Hsu et al. (22) proposed a possible mechanism for the maturation process of SARS-3CLpro from their crystal structure study of the C145A mutant. As the active site of one protomer in the C145A dimer binds with the C-terminal 6 amino acids of the protomer from another asymmetric unit, they believe that this kind of structure mimics the product-bound form in the maturation process. They also attached 10 extra residues at the N terminus and/or the C terminus of the protein and found that these proteins also form dimers, although weaker when compared with the matured enzyme. In their mechanism model, for the first and second step, two monomers of the polyprotein first cleave each other to cut off the N-terminal extra peptides and then form a dimer. That is, the first step of the reaction occurs between the two monomers within one dimer.

However, our data showed that the polyproteins with extra proteins at both ends can still form dimeric structure under substrate induction condition, which prompts for an intermolecule reaction mechanism. For the case of HIV protease maturation, during the first step of digestion, the full-length HIV polyprotein also forms dimer by prerequisite and cuts the N-flanking site intramolecularly as the initial rates related to N-terminal autocleavage linearly increased along with the increase of the polyprotein concentration (30). In contrast, our results indicated that the initial rates for the SARS polyprotein related to the N-terminal or C-terminal autocleavage non-linearly increased along with the increase of the polyprotein concentration. That is, the SARS polyprotein may cut its termini intermolecularly. In fact, this is also in accordance with the crystal structure of Hsu et al. (22) as they observed that a dimer molecule of the C145A mutant binds with the C-terminal 6 amino acids of the protomer from another asymmetric unit.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed an updated version for the SARS-3CLpro maturation mechanism (Fig. 7). Shortly after the polyprotein translation, a tiny amount of transient dimers can form, which become more stabilized by binding to its substrate (another polyprotein), and then an intermolecular reaction occurs to release the free N terminus of SARS-3CLpro in the polyprotein. The one-step product, with a free N terminus but a restricted C terminus of 3CLpro, can be induced into the dimer form more easily by the substrate and is more active than its precursor, which will make it act as the main enzyme to cut the N-terminal flanking site of the other molecules in the polyprotein in step two. In the third step, the one-step product digests its C-terminal flanking site to release the free C terminus of 3CLpro monomer. In the fourth step, along with the accumulation of 3CLpro monomers, active dimers were assembled by two protomers to form matured 3CLpro.

FIGURE 7.

Possible mechanism of 3CLpro autoprocessing. In the first step, polyproteins A and B form a transient dimer, which cuts the N-terminal flanking site of molecule C (and D, etc.). In the second step, molecule C and D with a free N terminus but a restricted C terminus of 3CLpro form a dimer and act as the main enzyme to cut molecule A or B through trans-cleavage. For the third step, the truncated polyprotein with free N terminus digested its C-terminal flanking site to release the free C terminus of 3CLpro monomer. For the fourth step, monomers of the matured enzyme assembled into an active dimer of 3CLpro.

As the substrate-induced dimerization occurs at each step when compared with the conventional “power of two” mechanism (10), this “substrate-dependent power of two” mechanism provides an additional way of enzyme activity regulation. For example, at the very beginning of viral replication, only a very low concentration of the enzyme and the substrate is present, so nothing will happen. Along with the polyprotein synthesis, substrates are accumulated, which then induce more enzyme dimer formation and activate the process of the enzyme digestion. Then along with the digestion reaction, the concentration of substrate will be lowered, whereas the matured enzyme concentration will be increased. As the matured enzyme has a stronger dimer association constant, its increased concentration results in more active dimers to treat the low concentration of substrate until most substrates are consumed. This kind of enzyme activity regulation is a highly efficient and economic way of activity control and substance usage. We expect that in addition to other 3CLpro proteinases, more examples of multidomain proteins may also follow this type of dynamic control mechanism.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in part, by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Experimental Procedures, Figs. S1–S5, and Tables S1–S4.

- SARS

- severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV

- SARS coronavirus

- 3CLpro

- 3C-like proteinase

- 3CLP

- 3CLpro

- XX

- SITSAVLQ

- C

- cyan fluorescent protein

- Y

- yellow fluorescent protein

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- HIV

- human immunodeficiency virus

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- AUC

- analytic ultracentrifugation

- 5f

- 1-(2-naphthlmethyl) isatin-5-carboxamide

- pNA

- 4-nitroaniline

- EGS

- ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ziebuhr J. (2005) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 287, 57–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand K., Palm G. J., Mesters J. R., Siddell S. G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3213–3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J. R., Hilgenfeld R. (2003) Science 300, 1763–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan K., Wei P., Feng Q., Chen S., Huang C., Ma L., Lai B., Pei J., Liu Y., Chen J., Lai L. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1637–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H., Wei P., Huang C., Tan L., Liu Y., Lai L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13894–13898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei P., Fan K., Chen H., Ma L., Huang C., Tan L., Xi D., Li C., Liu Y., Cao A., Lai L. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 339, 865–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S., Hu T., Zhang J., Chen J., Chen K., Ding J., Jiang H., Shen X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 554–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi J., Sivaraman J., Song J. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 4620–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu T., Zhang Y., Li L., Wang K., Chen S., Chen J., Ding J., Jiang H., Shen X. (2009) Virology 388, 324–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marianayagam N. J., Sunde M., Matthews J. M. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 618–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron C. E., Grinde B., Jacques P., Jentoft J., Leis J., Wlodawer A., Weber I. T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 11711–11720 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darke P. L., Cole J. L., Waxman L., Hall D. L., Sardana M. K., Kuo L. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7445–7449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marnett A. B., Nomura A. M., Shimba N., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Craik C. S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6870–6875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz I. C., Marcotrigiano J., Dentzer T. G., Rice C. M. (2006) Nature 442, 831–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wlodawer A., Miller M., Jaskólski M., Sathyanarayana B. K., Baldwin E., Weber I. T., Selk L. M., Clawson L., Schneider J., Kent S. B. (1989) Science 245, 616–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang C., Louis J. M., Aniana A., Suh J. Y., Clore G. M. (2008) Nature 455, 693–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C., Wei P., Fan K., Liu Y., Lai L. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 4568–4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan K., Ma L., Han X., Liang H., Wei P., Liu Y., Lai L. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329, 934–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai L., Han X., Chen H., Wei P., Huang C., Liu S., Fan K., Zhou L., Liu Z., Pei J., Liu Y. (2006) Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 4555–4564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang H., Bartlam M., Rao Z. (2006) Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 4573–4590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shan Y. F., Li S. F., Xu G. J. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 579–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu M. F., Kuo C. J., Chang K. T., Chang H. C., Chou C. C., Ko T. P., Shr H. L., Chang G. G., Wang A. H., Liang P. H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31257–31266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiel V., Ivanov K. A., Putics A., Hertzig T., Schelle B., Bayer S., Weissbrich B., Snijder E. J., Rabenau H., Doerr H. W., Gorbalenya A. E., Ziebuhr J. (2003) J. Gen. Virol. 84, 2305–2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei P., Li C., Zhou L., Liu Y., Lai L. (2010) Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 26, 1093–1098 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L., Liu Y., Zhang W., Wei P., Huang C., Pei J., Yuan Y., Lai L. (2006) J. Med. Chem. 49, 3440–3443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziebuhr J., Snijder E. J., Gorbalenya A. E. (2000) J. Gen. Virol. 81, 853–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibbles K. W., Brierley I., Cavanagh D., Brown T. D. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 1923–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piñón J. D., Mayreddy R. R., Turner J. D., Khan F. S., Bonilla P. J., Weiss S. R. (1997) Virology 230, 309–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiller J. J., Kanjanahaluethai A., Baker S. C. (1998) Virology 242, 288–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louis J. M., Nashed N. T., Parris K. D., Kimmel A. R., Jerina D. M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 7970–7974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.