Abstract

Pulmonary surfactant is essential for lung function. It is assembled, stored and secreted as particulate entities (lamellar body-like particles; LBPs). LBPs disintegrate when they contact an air-liquid interface, leading to an instantaneous spreading of material and a decline in surface tension. Here, we demonstrate that the film formed by the adsorbed material spontaneously segregate into distinct ordered and disordered lipid phase regions under unprecedented near-physiological conditions and, unlike natural surfactant purified from bronchoalveolar lavages, dynamically reorganized into highly viscous multilayer domains with complex three-dimensional topographies. Multilayer domains, in coexistence with liquid phases, showed a progressive stiffening and finally solidification, probably driven by a self-driven disassembly of LBPs from a sub-surface compartment. We conclude that surface film formation from LBPs is a highly dynamic and complex process, leading to a more elaborated scenario than that observed and predicted by models using reconstituted, lavaged, or fractionated preparations.

Keywords: Lipid Absorption, Lung, Membrane Biophysics, Membrane Fusion, Pulmonary Surfactant, Air-Liquid Interface, Lamellar Bodies, Surface Tension

Introduction

Pulmonary surfactant is essential to form surface active films at the respiratory air-liquid interface, and so to minimize the work of breathing. It forms a continuous network of membrane-based structures, which reduce surface tension and facilitate lung inflation (1). Surfactant is assembled in lamellar bodies of alveolar type II (AT II)3 cells as densely packed membranous structures, which maintain this compact organization after release into the extracellular fluid, constituting what was termed lamellar body-like particles (LBPs) (2). Upon adsorption, LBPs transfer surface active components into the air-liquid interface. The mechanisms that have been proposed to promote this transfer include (a) a surface tension-dependent rupture, or unpacking, of the entire particle, followed by a lateral spreading of its contents at the interface (2), (b) unfolding of LBPs and their rearrangement into single but interwoven lipid bilayers (tubular myelin) that feed the interface via monolayer/bilayer contact sites (3), and (c) decomposition and fragmentation of LBPs into other smaller functional units within the alveolar lining fluid (4) or the interface (5). At present, all these mechanisms seem possible, but the relative contribution of each of them in vivo is not known (6).

In classical views of surfactant function, adsorbed material forms a stable monolayer, supposedly enriched in DPPC, able to tolerate high lateral compressions at inspiration, and re-expands after surface relaxation (7). More recently, it has been proposed that interfacial lipid/protein complexes are interconnected with subsurface aggregates (1, 8, 9). Moreover, a coexistence between ordered and disordered phases is perceived (9–12), whose occurrence and significance under the actual physiological constraints is still under debate, with surfactant proteins (SP-A, -B, and -C) playing roles in the reversible translocation and stabilization of surface films (reviewed in Ref. 1).

Here, we investigated surface film formation by LBPs at an inverted air-liquid interface (10) by fluorescence microscopy of phase selective dyes (Bodipy-PC and DiI). Previous studies had shown that differential partition properties of these two probes permit detection of segregated fluid-ordered (DiI) and fluid disordered (Bodipy-PC) regions in surfactant membranes (11, 12). Here, fluorescence staining permitted detection of phase separation but also the accumulation of surfactant into multilayers. Additionally, surface topography was mapped by conventional and scanning reflected-light microscopy. The images obtained produced a true three-dimensional representation of the texture of the surfactant film. Beside the methods used, the strength and novelty of our approach is the fact that we used surfactant directly in the form it is secreted (2). This is important because whole bronchoalveolar lavage, from which natural surfactant preparations are usually obtained, collects structures from different regions of the respiratory tract, and may contain material that is already considerably modified and/or does not necessarily contain the intact functional complexes as they are preassembled within the cells. Furthermore, we performed the experiments at 37 °C and 100% rH. Both factors are normally not considered in traditional surface biophysical measurements because of technical difficulties, except in the captive bubble surfactometer, where optical inspections with high resolution are not applicable (13). Our measurements demonstrated that LBPs form, through a highly dynamic reorganization, interfacial films with defined two-dimensional and three-dimensional complexities and very limited lateral diffusion. Possible impacts on our understanding of the in vivo situation, as well as differences in the biophysical behavior as compared with other surfactant materials, are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Solutions

Chemicals were from Sigma, Bodipy-PC [2- (4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine], and DiI [1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate] from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes. The bulk solution contained, in mm: NaCl 140, KCl 5, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 2, HEPES 10 (pH 7.4).

Surfactant Preparations

LBPs were harvested from the supernatants of purified rat AT II cells grown on Petri dishes, stimulated for 6 h at 37 °C with intermittent shaking by ATP (100 μm) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (100 nm) in bulk solution supplemented with antibiotics as described (2). With this stimulation, AT II cells release a considerable amount of surfactant phospholipids and proteins (14–16). After collection, supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use. Morphology of LBPs was analyzed by transmission EM of re-thawed samples (see below). They showed different packing densities and were partially disorganized (Fig. 1A). Tubular myelin was not detectable. Before use, suspended LBPs were also routinely labeled with FM 1–43 and inspected by microscopy for a particulate appearance (2). Phospholipids were quantified by phosphorous analysis or by choline determination as described (17). Surfactant from porcine lung lavages was purified and separated from blood components by NaBr density-gradient centrifugation (18). This preparation presumably contained both large and small aggregates. Stock solutions of Bodipy-PC and DiI were prepared in DMSO (1 mg/ml). Surfactants were stained, by incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, with an equimolar mixture of Bodipy-PC and DiI at a total dye/surfactant molar ratio of 3%. For FRAP, LBPs were stained only with Bodipy-PC (3% mol/mol).

FIGURE 1.

Morphology of LBPs and their content of surfactant-associated proteins. A, transmission EM. LBPs appear as partially unraveled lamellated whorls, intermixed with vesicular structures and plane membrane patches. B, representative Western blots (n = 3). PS, purified surfactant; PP, purified proteins.

Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

For analysis of SP-A and SP-D content, SDS/PAGE was performed using 12% acrylamide gels under reducing conditions, in the presence of 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a semidry transfer system at 20 V for 20 min. For analysis of SP-B and SP-C, 16% acrylamide gels were run under non-reducing conditions, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences) or PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), respectively, using a wet transfer system at 300 mA for 1 h. Blocking, washing, and incubation with the antibodies were performed using a protein detection system under vacuum (SNAP i.d., Millipore Corp.). The primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-SP-B (1:5000), rabbit anti-mature-SP-C (1:7000), mouse anti-SP-D (1:5000) (all from Seven Hills Bioreagents, OH), and rabbit anti-SP-A (1:2000) (kindly supplied by Dr. J. Wright, from Duke University). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (1:10000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-mouse peroxidase conjugated (1:10000) (Sigma Aldrich). Positive controls loaded in the corresponding westerns were 0.1 μg of SP-A and SP-D, and 0.5 μg of SP-B and SP-C. Both hydrophobic proteins were purified from porcine surfactant through organic extraction and gel-penetration chromatography. SP-A was a human protein generously given by Dr. C. Casals, from Universidad Complutense, and SP-D control was a recombinant SP-D form kindly provided by Dr. E. Crouch, from Washington University at St. Louis. LBPs were concentrated by ultracentrifugation before being loaded in the gels. They contained, as surfactant purified from lavages, the entire protein spectrum except SP-D (Fig. 1B).

Electron Microscopy

A volume of 10 ml of LBPs with a lipid concentration of 32.3 μg/ml was fixed by incubation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (TAAB) for 6 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation and washing with phosphate buffer 0.1 m, the pellet was post-fixed with osmium tetroxide (TAAB) 1% for 1 h and washed again three times with distilled water for 10 min each. Dehydration of the samples was performed with increasing concentrations of acetone from 30 to 100%, incubating each solution for 10 min. Infiltration with the Spurr resin (TAAB) was developed with the following concentrations of resin/acetone: 1/3 for 1 h, 1/1 for 1 h, 3/1 for 2 h, pure resin overnight, and pure resin 1 h. Resin polymerization was performed at 60 °C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections of the resin-embedded samples were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed with a JEOL 1010 transmission electron microscope (Jeol).

Inverted Interface Experiments

Previously, the inverted interface was used to analyze surfactant adsorption and surface film formation (2, 10). For this investigation, the setup was modified as follows: A glass coverslip (Fig. 2A) confines a space underneath the interface in which temperature and humidity could be kept constant by a slow convective flow of water-saturated air. The interface was thermostatted to yield 37 ± 0.1 °C in the air and fluid sides of the interface, respectively. By filling the chamber with buffered solution, a clean interface immediately formed at the aperture plane below. Thereafter, LBPs were added on top (2 μg into a final chamber volume of 1 ml), and came into contact with the interface by sedimentation. Surface properties (Figs. 8 and 9) were probed with micropipettes made of borosilicate, pulled to end with a closed hairpin (< 10 μm), and lowered by a micromanipulator 25 μm beyond the interface. Analysis of meniscus shape was performed by applying a threshold function as described in the legend to Fig. 9.

FIGURE 2.

Experimental and optical setups. A, top, chamber with the inverted air-liquid interface, bottom, enlarged view (dimensions not in scale). With this setup, exploration of interfacial phenomena is possible under defined (37 °C and 100% rH) conditions. B, optical setup combining synchronous dual emission (green and red) and light reflection imaging (see text; EM, emission; EX, excitation; LW, long, SW short wavelength).

FIGURE 8.

Stiffening of the surface coat. A, measurement of fluorescent bead mobility. Reflection images (top) illustrate the status of the interface at 0 and 60 min. Insets show the trajectories of surface-embedded fluorescent beads during 4 s exposure times used to analyze the covered distances. Left plot (mean ± S.D.; n = 24) reveals a slowdown of movements. Right plot, comparison at time 60 min with purified surfactant (PS) is shown in the bar chart (n = 6). B, a line crossing flat and light scattering regions along which FRAP was performed. Fluorescence recovery (%If) was measured in the indicated regions (n = 5) and purified surfactant (n = 6). C, microtip-induced surface mobility (see also Fig. 9). Tip movement was along dashed lines with a stop at the circles. Arrows indicate evoked movement of selected surface structures before and after tip movement.

FIGURE 9.

Estimation of local surface tension. A, puncture of the interface by a glass μtip enforces a fluid meniscus whose shape is depending on surface tension, contact angle, and gravitation (wetting is assumed to be complete). Meniscoid curvature can be analyzed by the microscope's image function upon epiillumination: Incident light from the objective is reflected to, or away from, the objective, depending on the angle of the surface. Below a critical incident angle (C.a.), light back reflection into the objective approaches zero (gray region). a and b illustrate 2 different menisci (as a result of different surface tensions), leading to the corresponding diameters a′, b′ of central dark image regions, the areas of which were used to estimate surface tension. B, line scans through the tip center (along dashed line in image) were used to define a threshold level (gray dotted line). Pixels with intensities below were used to calculate the central dark area (indicated by the bright circle) of diameter b′. According to A, a decrease in surface tension (e.g. by LBPs) leads an increase in the area below the threshold (a′). C, evaluation and results of the method, using the calculated dark areas and different surfactants, all at 37 °C and 100% rH. All surfactants yielded statistically different values (p ≤ 0.025) except DPPC compared with purified surfactant. Different concentrations within each group were not different. D, example of a measurement with LBPs. Top, only flat regions were used for C. Bottom, light scattering structures resisted penetration. They were lifted (here: 10 μm), leading to an asymmetric shading (meniscus).

Fluorescence and Reflected Light Microscopy

Fluorescence and reflected light microscopy were performed by epiillumination (Fig. 2B) with an inverted microscope (Zeiss 100) and a dry objective (Plan-Neofluar, 20×, N.A. 0.5; Zeiss). The light source (Polychrome II, Till Photonics) allowed a quick change (< 5 ms) between 470 nm (fluorescence) and 620 nm (reflection). Light was further filtered by a dualband excitation filter (480/593) and directed by the first dichroic beam splitter (505) toward the interface. Fluorescent or reflected light, after passing the first dichroic, were split by a second dichroic (565) mounted in a real-time dual color imaging device (Dual-View, Optical Insights). Split images either passed a 510 ± 10 nm for Bodipy-PC or a 630 ± 50 nm filter for DiI or reflected light. The two images were displayed on separated parts of a CCD chip (Imago-SVGA, Till Photonics), operated at an acquisition rate of 1 frame/3 s and a binning factor of 2. Using this optical configuration, Bodipy-PC and DiI fluorescence could be recorded synchronously, followed by reflection images taken 10 ms thereafter. Furthermore, crosstalk between the channels was negligible: light reflection did not contribute to fluorescence, nor was DiI emission (red) detectable in the green channel (Bodipy), whereas 3% of Bodipy emission bleached into the red one. However, Bodipy-PC at high concentrations is subject to self-quenching and to an increase in its Stoke's shift (19). Both artifacts have to be taken into account.

Laser Scanning Microscopy

A Zeiss Laser Scan Microscope (LSM 410) equipped with an argon (488 nm; 60 milliwatt) and a helium-neon laser (543 nm; 0.5 milliwatt) and a Plan-Neofluar, 20×, N.A. 0.5 was used for FRAP and z-stacking of the interfacial film. For FRAP, Bodipy-PC was visualized by the argon laser attenuated to 10% and bleached by operating it at full power for 2 min. Emitted light was directed through a > 515 nm filter before entering the photomultiplier tube. For z-stacks, Bodipy-PC was visualized as above, whereas DiI and reflection images were taken with the helium-neon laser. DiI and reflection images were separated by inserting or removing, respectively, a long-pass filter (>620 nm) in the light path.

Image Analysis and Statistics

Mean fluorescence intensity (If) indicates the intensity per unit of area (pixels), If-bg denotes background corrected If. Background was determined from a clean air-liquid interface. Thus, If-bg excludes fluorescence from the bulk and scattered light. However, all images are shown without background correction. Image and data analysis was performed with Till Vision, ImageJ, Microsoft Excel and Prism. We used unpaired t-tests, and data are reported as arithmetic mean of three independent experiments ± S.E. (unless otherwise indicated).

RESULTS

Initial Events of Surface Coverage

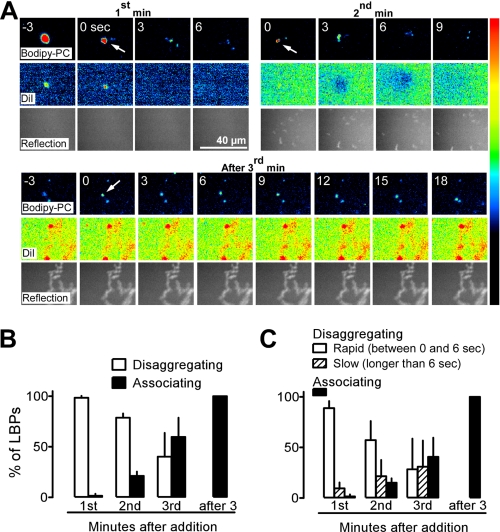

Within the 1st min after addition, LBPs contacting a clean interface (γ ≈72 mN/m) instantaneously and spontaneously disaggregated (defined as sudden disappearance of particulate fluorescence, Fig. 3A, 1st min). Disaggregation was fast (<6 s in 88.8 ± 7.0% of all events, Fig. 3C), particularly for the very first LBPs (<3 s in 71.4%, disaggregation occurred in 100%). Upon adsorption, phospholipids freely dispersed and covered the interface as unmasked by augmented fluorescence within areas devoid of particles (Fig. 3A, 2nd min). Thus, LBPs rapidly formed a phospholipid-based interfacial layer. Disaggregation of LBPs arriving after the 1st min became less common and slowed down, and terminated completely after the 3rd min (Fig. 3, B and C).

FIGURE 3.

Early adsorption events. A, two different mechanisms of LBPs adsorption: Rupture (disaggregation) of LBPs when they contact an interface free of phospholipids (1st min) or at low surface coverage (2nd min), and association of LBPs with reflective surface structures at saturating conditions (after 3rd min). Simultaneous detection of Bodipy-PC and DiI fluorescence unmasks phospholipid phase organization, reflection microscopy maps interface topography, and reveals surface structures. Time of interface contact is denoted by the arrows, acquisition rate = 0.33 fps. B, time-dependent categorization of interfacial adsorption events: Disaggregating denotes LBPs with sudden loss of point-shaped fluorescence, associating LBPs those which retained a particulate appearance. C, disaggregating LBPs were further subdivided according to the velocity of disaggregation.

Late Events of Surface Coverage

LBPs constantly approached the interface for the entire duration of the experiments (1 h), revealed by a nearly linear increase in the fluorescence intensity of both dyes (Fig. 4C). However, after the initial phase (3 min), the organization of surfactant and the behavior of LBPs changed notably: highly reflective structures appeared in form of irregular dots (Fig. 3A, 2nd min, reflection). These dots, probably surfactant in bi- or multilayers, but not compact LBPs, freely moved and by contact with each other or the capillary walls aggregated into coral-like structures that primarily stained with DiI (Fig. 3A, after 3rd min). At this time, LBPs moving through regions of low reflectance slowly associated with the reflecting structures (Fig. 3, A, after 3rd min, B and C). Thus, highly reflective coral-like structures developed by association of material already present at the interface in form of multilayer domains, or by direct incorporation of newly arriving LBPs. Accumulation of surfactant within these structures also led to lateral growth and development of three-dimensional topographies, visible as light scattering structures in Fig. 4A. Within the first 5 min, these textures already occupied a large portion of the interface (26.6 ± 14.6%). Thereafter, their growth abruptly slowed down but still continued, and after 60 min 81 ± 3.5% of the interface was covered (Fig. 4, A and B). The whole process of LBPs adsorption, interfacial transfer of material and its organization into two-dimensional and three-dimensional segregated structures can be seen in the supplemental movie. The three channels, running synchronously, show how the three-dimensional structures (presumably multilayer aggregates; left), Bodipy-PC labeled areas (presumably liquid-disordered states; center) and DiI-labeled regions (presumably liquid-ordered phase; right) appear and evolve in the film within 1 h of experiment (compressed to one frame/15 s).

FIGURE 4.

Entire sequence of film formation by LBPs. A, enlarged view demonstrates optically flat (low reflectance) and highly reflective, light scattering regions. B, growth of reflective, light scattering structures with time (in % of total surface area occupancy). C, increase in overall and phase selective fluorescence. Surfactant accumulation was almost linear with a tendency to slow down during the last 10 min.

Organization of Surfactant into Multilayer Structures

Bodipy-PC and DiI incorporated within light scattering regions (Figs. 4A and 5B). In contrast, the intensities of both dyes in “flat” regions only slightly increased. Fluorescence analyses suggest that light scattering regions were formed by the build-up of surfactant into multilayers whereas flat regions are phospholipid monolayers. Accumulation of surfactant in light scattering regions is also shown by the ratio of dye intensities (Fig. 5C). Distribution of Bodipy-PC between multi- and monolayers plateaued after ∼25 min, obviously indicating equal partition between domains. Similarly, but later (at ∼50 min), also the DiI ratio leveled off. To compare the proportion of the dyes in one region, the background corrected intensities of each dye were normalized for their total intensity at the interface at any given time (practically, values in Fig. 5B were divided by those in Fig. 4C). The results (nIDiI-bg for DiI and nIBodipy-PC-bg for Bodipy-PC) were independent of differences in amounts and/or fluorescence efficiencies of the dyes, which may contribute to the divergence seen in Fig. 4C. As shown in Fig. 5D, Bodipy-PC prevailed over DiI in flat regions, suggesting a primarily liquid expanded state here. However, also in these regions, a coexistence of liquid expanded and ordered phases was observed (Fig. 6A). Conversely, DiI prevailed in light scattering regions, especially during the early stages (<10 min). Thereafter both dyes were nearly balanced (Fig. 5D). A marked phase separation could be seen within multilayer regions (strong light scatter), during their growth (Fig. 6B): DiI accumulated preferentially in spots at the border of these regions, whereas Bodipy-PC distributed more evenly. Moreover, light scattering structures without correspondence in fluorescence were observed, probably denoting surfactant in a gel-like phase excluding both dyes (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of surface domains. A, exemplary binary image (right) derived from the original reflection image (left). Black denotes flat regions; white, light scattering regions. Binary images were used to separate dye intensities within the two domains. B, distribution/accumulation of Bodipy-PC and DiI in light scattering or flat regions. In flat regions, the two dyes almost overlap. C, fluorescence intensities (If-bg) in light scattering (L.S.) regions in relation to those in flat regions demonstrate the partition of the dyes between the two domains. D, normalized intensities (see text) of DiI (nIDiI-bg) in flat or light scattering regions, divided by those of Bodipy-PC within the same domains. Plot of this ratio shows the varying proportion of the dyes within each region.

FIGURE 6.

Segregation of liquid ordered and expanded phases as revealed by Bodipy-PC and DiI. A, within flat regions at 15 min. B, distribution of Bodipy-PC and DiI with respect to the surface topography (reflection) at 30 min. Enlarged views are the areas within the white squares, black bar, 30 μm. C, appearance of the surface film originating from surfactant purified from lung lavages. Experimental conditions in B and C are identical.

In contrast to LBPs, surfactant purified from lung lavages behaved considerably different (Fig. 6C). Whereas optically flat regions (low reflectance) were similar, prominent light scattering structures did not develop. Instead, regions of high reflectivity but low light scatter were seen. Moreover, dye separation was more pronounced than compared with LBPs: Bodipy-PC preferentially stained the low reflective regions and DiI, completely absent there, concentrated within the highly reflective ones. As with LBPs, regions in a gel-like type of phase, excluding both dyes, were observed.

The lateral and the spatial organization of interfacial structures were studied by LSM. Images from different focal planes (Fig. 7, A and B) demonstrate that multilayers have an extension in the z-direction. Analysis of fluorescence contrast and defocus aberration (Fig. 7, A and C; lines 1 and 2) unveiled that these three-dimensional structures are present in the subphase and also extend into the air. On the other hand, the lateral distribution of the dyes largely corresponded throughout the region imaged in Fig. 7A. Noteworthy, the intensity profiles of DiI and Bodipy-PC (Fig. 7, A and D, line 3) showed a stepwise distribution, again suggesting accumulation of surfactant within multilayer domains. Moreover, it revealed that dye co-localization was particularly high at the border of flat and light scattering regions (right end of line 3), but low toward their center (central and left part of line 3).

FIGURE 7.

Line scan and defocus aberration measurements. A, Z-scans of LBPs-derived membranes stained with Bodipy-PC and DiI. Reference Z-level (0 μm) was set to the focal plane of the flat region. Thus, −2 and +2.5 μm indicate in-focus structures shifted by 2 μm toward the subphase or 2.5 μm toward the air. Lines indicate calculation of intensity profiles plotted in C and D. B, reflected light image of the same region. Focal plane was at 0 μm. C, intensity profiles at different focal planes of lines 1 and 2 in A illustrate loss of fluorescence contrast at “out-of-focus” Z-levels. The focal plane of line 1, for example, is 2.5 μm above the level of the flat interface (sharp intensity profile of gray line), whereas that of line 2 is 2 μm below (sharp intensity profile of black line). D, intensity profiles of Bodipy-PC and DiI along line 3. For the ease of comparison, the size of the images in A and B (30 × 30 μm) correspond to the black bar in the enlarged view of Fig. 6B.

Dynamic Properties of the Surfactant Film

Fluorescent beads (1 μm) were embedded at the interface, and their random motion quantified by long exposure times (Fig. 8A). Before applying LBPs (at time 0), motions were 19.0 ± 6.8 μm/s, and slowed down during ongoing LBP-sedimentation and almost terminated at full surfactant coverage (0.13 ± 0.2 μm/s). This “stiffening”, similarly observed with purified surfactant (0.46 ± 0.47 μm/s), was further investigated by FRAP (Fig. 8B). Flat regions showed a recovery of 82.4 ± 11.5% of initial fluorescence within 10 min, light scattering regions 10.0 ± 4.0%, and border regions were in between (30.1 ± 13.2%). Recovery rates in purified surfactant were significantly higher (45.2 ± 3.6%) than those in light scattering regions of LBPs, but significantly lower than in flat regions (p ≤ 0.0025). The different results compared with the bead experiments are certainly related to the fact that FRAP is providing a region-dependent information, and that it is more sensitive for molecular movements than video microscopy of almost stagnant beads. Consistent with FRAP, and in contrast to purified surfactant, movements of a microtip inserted through the interface was barely transduced to adjacent surface structures (Fig. 8C), demonstrating a different rheological behavior of both surfactant films. Finally, penetration of the interface by glass μtips and qualitative analysis of meniscus shape suggested a very low surface tension of LBPs-formed films, significantly lower than the equilibrium surface tension of a film of pure DPPC or a film formed from whole surfactant purified from lavage (Fig. 9). However, solid structures resisted penetration and were lifted by several μm (>50 μm), forming irregular but stable (>1 h) menisci, which suggest coexistence of regions with differing viscous properties, surface tensions, and/or layer thicknesses.

DISCUSSION

Traditional models of lung surfactant considered that stability of the alveolar spaces depend on the formation of DPPC-enriched monolayers at the air-water interface (recently reviewed in Ref. 20). Films of DPPC, the most abundant molecular component in surfactant, are able to sustain very low surface tensions (<2 mN/m) upon compression (7). It has been also widely assumed that the essential character of the hydrophobic surfactant proteins, especially SP-B, is related with their ability to promote transference of surface active species from surfactant complexes into the interfacial film (21).

However, the present view of the structure and organization of surfactant films has evolved toward a more complex scenario. Surfactant membranes and films seem to possess additional levels of two-dimensional and three-dimensional complexity. Lipid composition of surfactant as purified from alveolar spaces promotes segregation of ordered and disordered phases, sorting the lipids and proteins in bilayers (11, 12) and interfacial films (22, 23). Presence of enough DPPC would be important to permit segregation of highly packed membrane patches, which provide mechanical stability to some extent. Some controversy exists with respect to the actual existence of such phase segregation in the lung, particularly at physiological temperature, humidity, and compression states (24). On the other hand, mechanical properties of surfactant films do not depend only on the behavior of single monolayered structures. Several evidences suggest that interfacial films are multilayered (9, 25), and that the cohesivity of these layers also contribute to sustain the high pressures reached at the end of exhalation (1). SP-B and SP-C could have essential roles in formation and maintenance of such interfacial surfactant reservoir, as well as to modulate its rheological behavior (reviewed in Ref. 1).

The results presented here show that the film formed by adsorption of LBPs could have further levels of complexity, starting with the formation of laterally heterogeneous films, which segregate regions with markedly different packing and molecular order (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with the sorting properties of the mixture of saturated and unsaturated lipid species in surfactant (11). We propose that ordered regions in LBPs-promoted films, those exhibiting dominant DiI fluorescence, could be enriched in DPPC and have properties similar to those of liquid-ordered phases. Such ordered regions seem to coexist with more disordered areas permitting the presence of bulky probes such as Bodipy-PC. Our results therefore confirm that the complex lipid composition in surfactant, as it is assembled in LBPs, could be prepared to generate stable and well-defined phase coexistence even under the most demanding physiologically relevant environmental conditions.

However, complexity of the surfactant films is not limited to the plane of the interface. Progressive adsorption of LBPs led to the appearance of large protruded three-dimensional structures, presumably accumulating multilayered material projecting toward the subphase and the air (Fig. 7). These light-scattering regions, which are not present in films formed by surfactant from lavages, seem to originate and grow through accretion of continuously arriving LBPs (see supplemental movie), acting as “sinks” for docking and attachment of LBPs (Fig. 3A). Although nucleation of protruded structures seems to occur often at the edges of the chamber, they also originated at its center, arguing against an artifactual contribution of the boundaries of the inverted interface. However, it cannot be discarded that nucleation and growth of three-dimensional structures could be promoted by surfactant films at singular locations of the alveolar spaces such as crevices, corners, or septae protruding into the alveolar lumen, reinforcing the mechanical resistance of the surface film at those spots. The existence of three-dimensionally complex surfactant films at the pulmonary alveolar interface has been occasionally reported, but the detection of projected structures such as those described here could have been hampered by the protocols traditionally used to prepare, fix, stain, and visualize lung tissue under the electron microscope. Application of some of the cutting-edge ultra-cryoelectron microscopy techniques developed in the recent years to minimally distorted lungs could help to elucidate the real existence of complex three-dimensional films such as those described here, in the distal airways.

Lamellar bodies contain a complex internal assembly of lipids and proteins (26). We speculate that they could have been pre-packed inside AT II cells in a sort of “energy-loaded” structure, accounting for the apparent spreading force to instantaneously deposit material when reaching the interface (Fig. 3). This hypothesis may gain additional support by the facts that lipid sorting into lamellar bodies is an ATP- and thus energy-driven process (27), that lamellar bodies appear to be under tension, which is partially relieved when the hemifusion state is reached (28), and that released LBPs show a faster initial rate of adsorption than natural surfactant (29). Such potential energy-loaded state of LBPs could also enable them to push and pack material within the preformed structures, creating condensation of ordered phases, and the projection of multilayered structures beyond the interfacial plane. Protein assemblies could be important for both the cooperative spreading of whole LBPs at high surface tensions and the establishment of multilayer interactions at lower ones. SP-B, which promotes formation of multilayered membrane arrays (30), could assist in docking LBPs to growing interfacial films and coupling adsorption with projection of three-dimensional structures.

The structures formed were absolutely repetitive and consistent, and also comparable when testing different LBPs concentrations, which affected the time-course of film generation but not its appearance. High LBPs concentrations reduced the time to form similar films to a few minutes. We propose that, at the high concentrations of secreted LBPs likely existing in the alveolar lining fluid, films similar to those shown here could be formed within seconds.

Adsorption of surfactant purified from alveolar lavage gives rise to a film with similar lateral complexity than observed in films formed by LBPs, including segregation of liquid-ordered, liquid-disordered, and gel-like regions. However, it lacked the prominent three-dimensional structures (Fig. 6) where “stiffening” of LBPs films was particularly high (Figs. 8 and 9). This suggests that the purified material could show only partially the properties of the film existing microns away of the pneumocytes. Caution should therefore be taken when trying to interpret the structure and behavior of surfactant from the study of preparations obtained from lavages, using environmental conditions that mimic the alveolar situation only partially. We did not detect large differences between LBPs and purified surfactant in terms of protein composition. Both materials contained comparable amounts of SP-B and SP-C with respect to phospholipids and practically no SP-D. The amount of SP-A detected in Western blots was somehow variable from batch to batch of both types of materials. This could be related with the fact that SP-A can be secreted through pathways independent of LBPs (31–33). However, although the behavior of LBPs and purified surfactant at the inverted interface was clearly distinct, it was highly repetitive and consistent when comparing different batches of each material. This seems to indicate that SP-A does not play a major role in defining the complexity of the interfacial structures observed. Still, the effect of the presence of defined amounts of SP-A and/or SP-D on the structure and the kinetics of formation of the interfacial film is an open question and will be subject of future investigation.

The most remarkable property of LBPs-formed films is their solid-like character. The complex three-dimensional structures have virtually no macroscopic mobility and practically no lateral diffusion in molecular terms (Fig. 8). This has been shown typically by surfactant films compressed close to collapse in surface balances (22, 23). It would presumably also be the state adopted by surfactant films at the minimal tensions reached in the captive bubble surfactometer (see e.g. (34)). Furthermore, the surface structures even showed a remarkable resistance to penetration with micropipettes (Figs. 8 and 9), and a rheological behavior that would classify them as “solidified” material. This, in our opinion, is consistent with the above hypothesis that the pre-packed structure of LBPs could promote the condensation and solidification of the interfacial film, even in the absence of external lateral compression, through an active ejection of material into the interface. Thus, the energy provided by the pumping activity of the lipid importer ABCA3 during lamellar body biogenesis (35) could be a driving force transmitted by LBPs to build a solidified surface film and to lower surface tension of flat regions below that produced by purified surfactant as suggested by qualitative meniscus shape analysis (Fig. 9). It remains to be determined, however, whether the film formed by LBPs is still compressible and what its actual surface tension really is. This, in our opinion crucial open question, may indicate whether the film is stabilizing the gas exchange surface in a sort of “frozen” state. Something in the same direction was in fact proposed by Bangham (36), who suggested that surfactant stabilizes alveoli by assembling a sort of “geodesic dome” of solidified surface patches, where a classical characterization by surface tension may not be really meaningful. The structure of the film created by LBPs seems to show properties consistent with such ideas. Furthermore, this “solid-like” interfacial network could play a major role to protect the delicate respiratory epithelium against potential distention imposed by lung mechanics. It is also plausible that alterations in the complex surfactant structure envisaged here, caused by lung injury and including leakage of different spurious materials into the alveolar spaces, could end in an inefficient protection of alveoli against mechanical distortion, triggering inflammation, and ultimately, the severe consequences of pathologies such as those associated with acute respiratory distress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Antonio Cruz for technical assistance and scientific discussions.

This work was supported by the Austrian FWF (P17501, P 20472), by Grants from Spanish Ministry of Science (BIO2009-09694, CSD2007-00010), and the Community of Madrid (S2009MAT-1507), and Marie Curie Network Pulmonet (RTN-512229) from the European Commission.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental movie.

- AT II

- alveolar type II

- LBPs

- lamellar body-like particles

- DPPC

- dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine

- rH

- relative humidity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pérez-Gil J. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1676–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller T., Dietl P., Stockner H., Frick M., Mair N., Tinhofer I., Ritsch A., Enhorning G., Putz G. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 286, L1009–L1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashchiev D., Exerowa D. (2001) Eur. Biophys. J. 30, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato S., Kishikawa T. (2001) Med. Electron Microsc. 34, 142–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veldhuizen R. A., Yao L. J., Lewis J. F. (1999) Exp. Lung Res. 25, 127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Gil J., Weaver T. E. (2010) Physiology 25, 132–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerke J. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1408, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Possmayer F., Nag K., Rodriguez K., Qanbar R., Schürch S. (2001) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 129, 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schürch S., Qanbar R., Bachofen H., Possmayer F. (1995) Biol. Neonate 67, Suppl. 1, 61–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertocchi C., Ravasio A., Bernet S., Putz G., Dietl P., Haller T. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 1353–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardino de la Serna J., Perez-Gil J., Simonsen A. C., Bagatolli L. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40715–40722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Serna J. B., Orädd G., Bagatolli L. A., Simonsen A. C., Marsh D., Lindblom G., Perez-Gil J. (2009) Biophys. J. 97, 1381–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schurch S., Bachofen H., Possmayer F. (2001) Comp. Biochem. Physiol A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 129, 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreeva A. V., Kutuzov M. A., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L259–L271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haller T., Ortmayr J., Friedrich F., Völkl H., Dietl P. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1579–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wemhöner A., Frick M., Dietl P., Jennings P., Haller T. (2006) J. Biomol. Screen. 11, 286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Verdugo I., Ravasio A., de Paco E. G., Synguelakis M., Ivanova N., Kanellopoulos J., Haller T. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 295, L708–L717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taeusch H. W., de la Serna J. B., Perez-Gil J., Alonso C., Zasadzinski J. A. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 1769–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahim M., Mizuno N. K., Li X. M., Momsen W. E., Momsen M. M., Brockman H. L. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 1511–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo Y. Y., Veldhuizen R. A., Neumann A. W., Petersen N. O., Possmayer F. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1947–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Gil J., Keough K. M. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1408, 203–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Discher B. M., Maloney K. M., Schief W. R., Jr., Grainger D. W., Vogel V., Hall S. B. (1996) Biophys. J. 71, 2583–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nag K., Perez-Gil J., Ruano M. L., Worthman L. A., Stewart J., Casals C., Keough K. M. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 2983–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan W., Biswas S. C., Laderas T. G., Hall S. B. (2007) J. Appl. Physiol. 102, 1739–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsson M., Nylander T., Keough K. M., Nag K. (2006) Chem. Phys. Lipids 144, 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams M. C. (1977) J. Cell Biol. 72, 260–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitsett J. A., Wert S. E., Weaver T. E. (2010) Annu. Rev. Med. 61, 105–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miklavc P., Albrecht S., Wittekindt O. H., Schullian P., Haller T., Dietl P. (2009) Biochem. J. 424, 7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravasio A., Cruz A., Pérez-Gil J., Haller T. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49, 2479–2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabré E. J., Malmström J., Sutherland D., Pérez-Gil J., Otzen D. E. (2009) Biophys. J. 97, 768–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher A. B., Dodia C., Ruckert P., Tao J. Q., Bates S. R. (2010) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 299, L51–L58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochs M. (2010) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 25, 27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rooney S. A. (2001) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 129, 233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gómez-Gil L., Schürch D., Goormaghtigh E., Pérez-Gil J. (2009) Biophys. J. 97, 2736–2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheong N., Zhang H., Madesh M., Zhao M., Yu K., Dodia C., Fisher A. B., Savani R. C., Shuman H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23811–23817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bangham A. D., Morley C. J., Phillips M. C. (1979) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 573, 552–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.