Abstract

Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP, MMP14), which is associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) breakdown in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), promotes tumor formation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. However, in this report we demonstrate that MT1-MMP, by cleaving the underlying ECM, causes cellular aggregation of keratinocytes and SCC cells. Treatment with an MMP inhibitor abrogated MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes, but decreasing E-cadherin expression did not affect MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation. As ROCK1/2 can regulate cell-cell and cell-ECM interaction, we examined its role in mediating MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes. Blocking ROCK1/2 expression or activity abrogated the cellular aggregation resulting from MT1-MMP expression. Additionally, blocking Rho and non-muscle myosin attenuated MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes. Moreover, SCC cells expressing only the catalytically active MT1-MMP protein demonstrated increased cellular aggregation and increased myosin II activity in vivo when injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Together, these results demonstrate that expression of MT1-MMP may be anti-tumorigenic in keratinocytes by promoting cellular aggregation.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Cell-Cell Interaction, Collagen, Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Matrix Metalloproteinase, Rho, Skin, MT1-MMP, Keratinocyte

Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)2 are a large family of highly conserved metalloendopeptidases with proteolytic activity directed against a variety of extracellular matrix (ECM) substrates (1–3). MMPs have been implicated in basement membrane proteolysis, activation of growth factors, and cleavage of cell-adhesion molecules. Extending mechanistic investigation to cancer biology, numerous studies have shown that MMP overexpression enhances the invasive activity of tumor cell lines (4–6). Analysis of human disease further supports the pro-tumorigenic role of MMPs, as increased expression of these proteases in tumor samples is clinically associated with invasion, metastasis, poor prognosis, and shorter survival times (7, 8). In the specific case of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), increased expression of membrane type 1-MMP (MT1-MMP, MMP14) is associated with ECM breakdown, tissue invasion, and lymph node metastasis (8).

However, several animal studies have now clearly demonstrated that multiple members of the MMP family provide a paradoxically protective effect during the relentless molecular destruction that characterizes malignant progression. MMPs may have been initially identified as potent pro-tumorigenic proteases, but their simultaneous ability to function in an opposing, anti-tumorigenic role is now equally well established (9, 10). Such data underscore both the complexity of MMP activity in cellular signaling events as well as the importance of stringently evaluating the context in which these proteases take on either an anti-tumorigenic or pro-tumorigenic role. Intriguingly, several recent studies using SCC models have begun to suggest a putative mechanism through which MMPs may be induced to function primarily as anti-tumorigenic proteases. When exposed to carcinogens, MMP3-null mice developed squamous cell skin cancers that not only grew faster but were also strikingly less differentiated than those of control animals (11). Significantly, orthotopic injection of MMP3-expressing tumor cells resulted in pronounced tumor cell differentiation (12). However, although such findings indicate that MMPs may inhibit SCC progression by promoting tumor cell differentiation, the precise mechanism through which these proteinases regulate this process has not yet been elucidated.

In normal tissue keratinocyte differentiation is a complex process mediated by cell-ECM and cell-cell interactions that subsequently activate downstream signaling pathways (13–15). Specifically, among structural proteins, integrins mediate primarily cell-ECM interactions, whereas cadherins are responsible for cell-cell interactions (13). In vitro activation of integrins or inhibition of cadherins after ligation or dominant negative expression, respectively, results in negative regulation of human keratinocyte differentiation (16–18). Furthermore, beyond structural proteins, Rho GTPases are also known to be an important component of keratinocyte differentiation pathways. Rho signaling has been shown to mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion (19–22), whereas the family of Rho proteins (RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC) mediates changes in gene expression leading to cell-cycle progression or differentiation in keratinocyte model systems (23–26).

In this report we demonstrate for the first time that MT1-MMP, a key proteinase that imbues cancer cells with the ability to invade and proliferate in the three-dimensional microenvironment (27), may also be anti-tumorigenic. Inducible expression of MT1-MMP in normal keratinocytes and SCC cells causes cellular aggregation with a subsequent decrease in the size of individual cells. These phenotypic changes were abrogated by blocking MT1-MMP catalytic activity and were significantly attenuated by plating cells onto type I collagen- or laminin-5-rich matrices instead of the typical tissue culture plastic. However, blocking E-cadherin expression using siRNA did not affect MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes. In contrast, inhibiting ROCK1/2 completely abrogated MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation. Additionally, we demonstrate that MT1-MMP-induced effects in SCC cells and keratinoctyes involve Rho and non-muscle myosin II. Finally, when SCC cells are injected into nude mice, cells expressing catalytically active MT1-MMP protein demonstrate increased cellular aggregation and myosin II activity. Together, these findings begin to characterize the complex and multifaceted roles of cellular proteases. In both normal and malignant keratinocytes, expression of MT1-MMP may result in an anti-tumorigenic effect by activating ROCK1/2 signaling pathways and enhancing cell-cell interaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Anti-MT1-MMP antibody and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Ham's F-12, and keratinocyte-SFM were purchased from Invitrogen. Anti-tubulin, anti-ROCK1 (K-18), and anti-ROCK2 (H-85) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-E-cadherin (HECD-1) antibody was purchased from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Anti-α2 integrin (P1E6), anti-α3 integrin (P1B5), and anti-β1 integrin (P4C10) antibodies were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA), and anti-phospho-myosin light chain 2 (Ser-19) antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). A nucleofector electroporation kit specifically designed for keratinocytes was obtained from Amaxa (Gaithersburg, MD). MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190, ROCK1/2 inhibitors H1191 and Y27632, myosin light chain inhibitor blebbistatin, and MMP inhibitor GM6001 were purchased from Calbiochem. A protease inhibitor mixture was purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Cell-permeable Rho inhibitor C3-tat was obtained from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO).

Cell Cultures

Tert-immortalized normal oral keratinocytes (OKF6 cells) were kindly provided by Dr. J. Rheinwald (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Institutes of Medicine, Boston, MA). These cells display normal keratin synthesis and can undergo stratified squamous epithelial differentiation (28). SCC25 cells were derived from squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and are tumorigenic in nude mice. SCC25 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (29). SCC25 cells were routinely maintained in DMEM and Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) containing 10% fetal calf serum and supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (4, 30). OKF6 cells were maintained in keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 25 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (supplied with the medium), 0.2 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 0.31 mm CaCl2 (31, 32).

Generation of MT1-MMP-inducible OKF6 and SCC25 Cells

The coding sequence for the full-length MT1-MMP, the catalytically inactive EA, and the tail-deleted DC mutants of MT1-MMP have been described previously (30) and were subcloned into pRetroX-Tight-Pur vector (33). All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. To generate retroviral particles, GP2–293-packaging cells were transfected with pRetroX-Tight Pur vector and cotransfected with pVSVG (Clontech) envelope vector according to the manufacturer's specifications (Clontech). The conditioned medium from the packaging cells containing the viral particles were filtered through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane and then added to the cells in the presence of Polybrene 4 μg/ml Initially, SCC25 and OKF6 cells were infected with viral particles expressing pRetroX-Tet-On Advanced vector, and stable cells resistant to G418 were selected to create SCC25-tet and OKF6-tet cells. These cells were then infected with viral particles containing pRetroX-Tight-Pur vector containing wild-type MT1-MMP, catalytically inactive EA mutant, the tail-deleted DC mutant or luciferase as control, and stable cell lines resistant to both G418 and puromycin were selected.

To examine the effect on cellular morphology, OKF6 and SCC25 cells were plated overnight on glass coverslips, treated with doxycycline for 24 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde solution for 10 min, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min, and stained with DAPI and E-cadherin, after which the cells were washed, mounted, and observed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope. To examine the effect of ECM on cellular phenotype, cells were plated onto tissue culture plates coated with type I collagen (BD Biosciences) or laminin-5 (30, 34).

Down-regulation of E-cadherin, ROCK1, and ROCK2 Expression

E-cadherin expression was transiently down-regulated using the following duplex siRNA directed against E-cadherin: forward primer (5′-GAUUGCACCGGUCGACAAAdTdT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-UUUGUCGACCGGUGCAAUCdTdT-3). OKF6 cells were transiently transfected with 100 nmol of E-cadherin specific siRNA or control siRNA using Amaxa nucleofector kit, allowed to recover overnight, serum-starved for 24 h, and treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microscopy. Similarly, ROCK1 was down-regulated using the duplex siRNA (ROCK1Si) forward primer 5′-GCCAAUGACUUACUUAGGAdTdT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-UCCUAAGUAAGUCAUUGGCdTdT-3′, whereas ROCK2 was down-regulated using the duplex siRNA (ROCK2Si) forward primer 5′-GCAAAUCUGUUAAUACUCGdTdT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGAGUAUUAACAGAUUUGCdTdT-3′ (35).

Analysis of MT1-MMP and MMP-2 Expression

MT1-MMP expression was determined by Western blotting using an antibody directed against the hinge region, whereas MMP-2 expression and activation was determined by SDS-PAGE gelatin zymography as described previously (2, 36).

Real-time PCR

Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA was performed using GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative gene expression was performed for E-cadherin, ROCK1, ROCK2, MT1-MMP, and GAPDH with gene specific probes (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and the 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The data were then quantified with the comparative CT method for relative gene expression (37).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells (5 × 105) were treated with monoclonal anti-α2-, α3-, or β1-integrin (1:100) for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were stained with secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500) for 30 min at 4 °C, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in PBS for analysis with Summit Software 4.3 on a Beckman Coulter fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

Growth of MT1-MMP-expressing Cells in Nude Mice

Mice were housed, fed, and treated in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Eight-week-old athymic nu/nu animals were injected into the dermis with 2 × 106 tet-on SCC25-tet-V on the left side, whereas SCC25-tet-MT cells were injected into the right side of the same animal. Similarly, following the same protocol, SCC25-tet-EA cells were injected on the left with SCC25-tet-DC cells injected on the right. Twenty-four hours later doxycycline was added to the drinking water to induce protein expression and monitored twice a week for the development of skin tumors up to 4 weeks post-injections. The mice were euthanized, after which the tumors were dissected and placed in RNAlater or 10% formaldehyde. The RNAlater-preserved tumors were processed and analyzed for human MT1-MMP and human GAPDH mRNA expression by real-time PCR. The formaldehyde-fixed tumors were embedded in paraffin, stained with H&E, trichrome by Gomori's method, or for phospho-myosin light chain (MLC) by an immunohistochemical method (38).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Instat 3 (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Induction of MT1-MMP Promotes Cellular Aggregation in SCC Cells

Because MT1-MMP-null mice have a phenotype characterized by profound musculoskeletal abnormalities due to their inability to process type I collagen (39, 40), the role of MT1-MMP in physiologic and pathologic processes has been extensively evaluated. Using constitutive expression in stable cell lines, MT1-MMP has been shown to promote invasion, proliferation, and growth in three-dimensional collagen gels (5, 41). However, because of concerns regarding selection bias in cells adapted to constitutively increased pericellular proteolytic activity, we generated cell lines in which a tet-on system allows for more precise and regulated expression of MT1-MMP. SCC25 cells were transfected with pTET vector and co-transfected with pTight vector expressing luciferase (V) or pTight vector expressing wild-type MT1-MMP (MT). Stable cell lines resistant to both G418 and puromycin were selected to generate SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-MT cell lines. These cell lines were subsequently plated in serum-containing media, serum-starved, and treated with doxycycline to induce gene expression of MTI-MMP. As shown in the upper panel of Fig. 1A, there was no induction of MT1-MMP in the absence of doxycycline, whereas doxycycline treatment induced robust protein expression. To further validate this system, we next examined the effect of MT1-MMP induction on the downstream target MMP-2 in SCC25. Although SCC25 cells show basal MMP-2 activation, doxycycline treatment significantly enhanced MMP-2 activation in the SCC25-tet-MT cells but not in the SCC25-tet-V cells (Fig. 1A, lower panel).

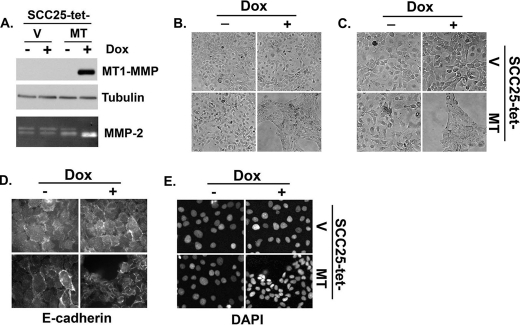

FIGURE 1.

Induction of MT1-MMP promotes cellular aggregation in SCC cells. Malignant SCC25 cells were transfected with pTet-on vector (Clontech) and co-transfected with either pTight-luciferase vector (V) or pTight vector expressing full-length wild-type MT1-MMP (MT). Stable cells resistant to both G418 and puromycin were selected to generate SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-MT cell lines. A, the stable SCC25 cells were plated overnight in serum-containing media, serum-starved for 24 h, and then treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h. Equal amounts of cell lysate were analyzed for MT1-MMP and tubulin (loading control) by Western blotting, whereas the conditioned media were analyzed for MMP-2 activation by gelatin zymography. B and C, the effect of MT1-MMP induction in SCC25 cells was examined at low (B) and high magnification (C) by phase microscopy. D and E, SCC25 cells were plated onto glass coverslips, and MT1-MMP expression was induced by treating the cells with doxycycline for 24 h. Cells were then fixed, stained with E-cadherin and DAPI, and examined with a fluorescence microscope. The results are representative of at least four independent experiments.

MT1-MMP expression has previously been shown to result in epithelial-mesenchymal transition with loss of cell-cell adhesion and increased scattering (42, 43). Consequently, after validation of our experimental system, we utilized phase microscopy to evaluate the effects of MT1-MMP induction on cell morphology. Surprisingly, induction of MT1-MMP in SCC25 cells resulted not in increased scattering but rather in marked cellular aggregation accompanied by a decrease in the size of individual cells (Figs. 1, B and C). To more clearly demonstrate the effect on cell size and aggregation, SCC25 cells were stained for a cell surface marker (E-cadherin) with DAPI nuclear counter-staining. E-cadherin staining showed MT1-MMP-expressing cells were significantly smaller than their control counterparts (Fig. 1D), whereas DAPI staining demonstrated decreased internuclear distance with increased cell density in the MT1-MMP-expressing cells (Fig. 1E).

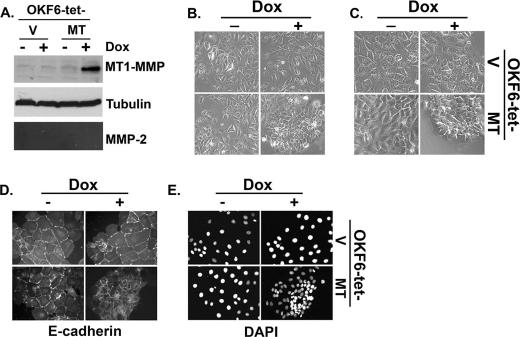

Inducible Expression of MT1-MMP Promotes Cellular Aggregation in Keratinocytes

In addition to SCC25 cells, we also examined the effect of inducing MT1-MMP on the cellular behavior of tert-immortalized OKF6 keratinocytes by generating OKF6-tet-V and OKF6-tet-MT cell lines. Because these cells do not express MMP-2 under basal conditions, OKF6 cells allow us to define contribution of MT1-MMP relative to MMP-2 in mediating cellular aggregation. Treatment of OKF6-tet-MT cells with doxycycline increased MT1-MMP protein expression (Fig. 2A) and induced cellular aggregation (Figs. 2, B and C), changes similar to those seen with SCC25-tet-MT cells. E-cadherin and DAPI staining of OKF6 confirmed that MT1-MMP induction resulted in cellular aggregation and decreased the size of the individual OKF6 cells (Figs. 2, D and E).

FIGURE 2.

Inducible expression of MT1-MMP promotes cellular aggregation in keratinocytes. Tert-immortalized keratinocytes (OKF6) were transfected with pTet-on vector (Clontech) and co-transfected with either pTight-luciferase vector (V) or pTight vector expressing full-length wild-type MT1-MMP (MT), and stable cells lines resistant to both G418 and puromycin were selected to generate OKF6-tet-V and OKF6-tet-MT cell lines. A, the stable OKF6 cells were plated overnight in serum-containing media, serum-starved for 24 h, and then treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h. Equal amounts of cell lysates were analyzed for MT1-MMP and tubulin (loading control) by Western blotting, whereas the conditioned media were analyzed for MMP-2 activation by gelatin zymography. B and C, the effect of MT1-MMP induction in OKF6 cells was examined at low (B) and high magnification (C) by phase microscopy. D and E, the cells were plated onto glass coverslips, and MT1-MMP expression was induced by treating the cells with doxycycline for 24 h. The cells were then fixed, stained with E-cadherin and DAPI, and examined with a fluorescence microscope. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

MT1-MMP-induced Cellular Aggregation Requires Protease Catalytic Activity

MT1-MMP can regulate cellular behavior not only through induction of catalytic activity but also by signaling through its short cytoplasmic tail (44–48). To determine which action(s) regulates morphologic changes in keratinocytes, we generated SCC25 cells expressing either the catalytically inactive EA mutant or the tail-less DC mutant of MT1-MMP using the tet-on expression system. Treatment with doxycycline showed comparable protein expression of wild-type MT1-MMP and the catalytically inactive EA mutant (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Consistent with the finding that the C-terminal tail regulates endocytosis and subsequent degradation of MT1-MMP protein (49, 50), the DC mutant was present at higher levels relative to the wild-type protein or the EA mutant (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Moreover, there was increased MMP-2 activation only by the wild-type MT1-MMP protein and the DC mutant, but not by the catalytically inactive EA mutant (Fig. 3A, lower panel). We then examined the effects of expressing inactive EA mutant protein or tail-less DC protein on the previously described phenotypic changes associated with MT1-MMP expression characterized by cellular aggregation and decreased cell size. Expression of the DC mutant protein induced similar phenotypic changes compared with wild-type MT1-MMP protein (Fig. 3B), suggesting that cytoplasmic tail signaling is not essential for induction of this phenotype. In contrast, however, expression of the catalytically inactive EA mutant induced minimal changes with phase microscopy demonstrating comparable cellular behavior when compared with control cells (Fig. 3B, upper panel).

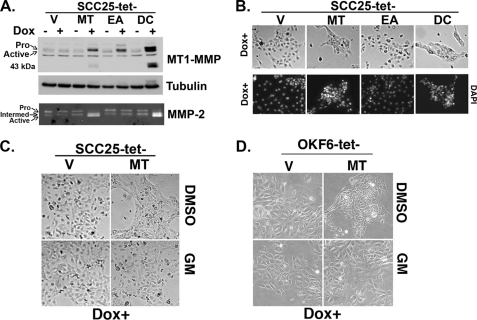

FIGURE 3.

MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation requires protease catalytic activity. A, stable SCC25-tet-V (V), SCC25-tet-MT (expressing wild-type MT1-MMP protein) (MT), SCC25-tet-EA (expressing the catalytically inactive E240A MT1-MMP mutant protein) (EA), and SCC25-tet-DC (expressing the tail-less mutant MT1-MMP protein) (DC) cells were plated overnight in serum-containing media, serum-starved for 24 h, and then treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h. Equal amounts of cell lysate were analyzed for MT1-MMP and tubulin (loading control) by Western blotting, whereas the conditioned media were analyzed for MMP-2 activation by gelatin zymography. B, the effect of expressing wild-type or mutant MT1-MMP protein in the SCC25 cells was examined by phase microscopy. In addition, stable cell lines were plated onto glass coverslips, and MT1-MMP expression was induced by treating the cells with doxycycline (Dox) for 24 h. The cells were then fixed, stained with DAPI, and examined with a fluorescence microscope. C and D, SCC25-tet-V, SCC25-tet-MT, OKF6-tet-V, and OKF6-tet-MT cells were treated with doxycycline for 24 h in the presence of MMP inhibitor GM6001 (GM, 10 μm) or vehicle control (DMSO), and the effect on cell phenotype was determined by phase microscopy. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

As with our initial MT1-MMP expression experiments, we next examined the effect of EA or DC mutant expression on cellular aggregation by DAPI nuclear counter-staining. Results from these experiments corroborate the significance of MT1-MMP catalytic activity in mediating changes in cell phenotype. Compared with control cells, EA mutant expression did not affect internuclear distance, but DC mutant expression led to decreased internuclear distance and increased cell density (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Because the effect of MT1-MMP overexpression, thus, seems to be mediated by the proteolytic action of its catalytic domain, we subsequently evaluated the effect of MMP inhibitor GM6001 on SCC25-tet-MT and OKF6-tet-MT cellular morphology. In a validation of our molecular data, pharmacologic treatment of both SCC25 (Fig. 3C) and OKF6 (Fig. 3D) cells with the MMP inhibitor GM6001 abrogated the effect of MT1-MMP expression, further supporting a role for increased proteolytic activity regulating phenotypic change.

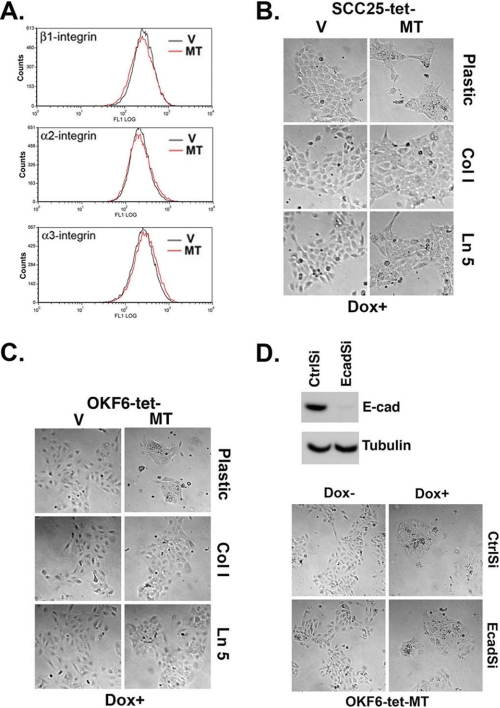

Laminin-5 and Collagen Type I Attenuate MT1-MMP-induced Cellular Aggregation

Prior studies have demonstrated that MT1-MMP can affect cellular behavior by cleaving integrins from the cell surface (47, 51, 52). Therefore, we induced MT1-MMP in SCC25 cells and used FACS analysis to examine subsequent effects on the relative cell surface levels of β1-, α2-, and α3-integrins. As shown in Fig. 4A, there was no difference in the relative levels of these integrins in the doxycycline-treated SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-MT cells. In addition, there was no difference in the relative levels of these integrins in the doxycycline-treated OKF6-tet-V and OKF6-tet-MT cells (data not shown). As cleavage of the underlying ECM is a well established MMP function, we next hypothesized that providing additional ECM structure could attenuate the effects of MT1-MMP expression (3). Because both type I collagen and laminin-5 can be cleaved by MT1-MMP (3), we evaluated the MT1-MMP expression phenotype after cellular exposure to either one of these two matrices or standard plating onto tissue culture plastic. SCC25-tet-V, SCC25-tet-MT, OKF6-tet-V, and OKF-6-tet-MT cells were plated onto tissue culture plastic, thin layer type I collagen, or laminin-5-rich ECM and treated with doxycycline. Induction of MT1-MMP in SCC25 (Fig. 4B) and OKF6 (Fig. 4C) cells resulted in cellular aggregation and a decrease in the size of individual cells; however, the effects induced by MT1-MMP expression were significantly diminished when cells were plated onto type I collagen or laminin-5.

FIGURE 4.

Laminin-5 and collagen type I attenuate MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation. A, SCC25-tet-V (V) and SCC25-tet-MT (MT) cells were plated overnight in serum-containing media, serum-starved for 24 h, and then treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h. The cells were then analyzed for α2- α3-, and β1-integrin expression by FACS analysis. B and C, SCC25-tet-V, SCC25-tet-MT, OKF6-tet-V, and OKF6-tet-MT cells were plated onto tissue culture plastic, a thin layer of type I collagen (Col I), or laminin-5 (Ln 5) and treated with doxycycline (Dox) for 24 h. The effect of the different extracellular matrices on MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic change was examined by phase microscopy. D, OKF6-tet-MT cells were transfected with 100 nmol of control siRNA (CtrlSi) or siRNA against E-cadherin (EcadSi), and cell lysates were analyzed for E-cadherin and tubulin (loading control) at 72 h by Western blotting. Forty-eight hours after transfection with CtrlSi or EcadSi, OKF6-tet-MT cells were treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microscopy. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

E-cadherin Does Not Regulate MT1-MMP-induced Phenotypic Changes

As E-cadherin is an important regulator of cell-cell adhesion in keratinocytes (16–18), we next evaluated the extent to which this protein is involved in the cellular aggregation induced by MT1-MMP. SCC25 cells express both E- and N-cadherin, whereas OKF6 cells express only E-cadherin (32); thus, we utilized siRNA to down-regulate E-cadherin expression exclusively in OKF6-tet-MT cells. Cells were transfected with 100 nmol of control siRNA or E-cadherin-specific siRNA, and the levels of mRNA and protein expression were determined at 72 h post-transfection. E-cadherin siRNA led to E-cadherin-specific mRNA knock down of >90% (data not shown) and effectively decreased E-cadherin protein in OKF6-tet-MT cells (Fig. 4D). After determining the efficacy of E-cadherin siRNA, we were able to demonstrate that loss of this protein had no effect on the phenotypic changes induced after MT1-MMP expression. With or without E-cadherin, MT1-MMP expression continued to drive increased cellular aggregation (Fig. 4D).

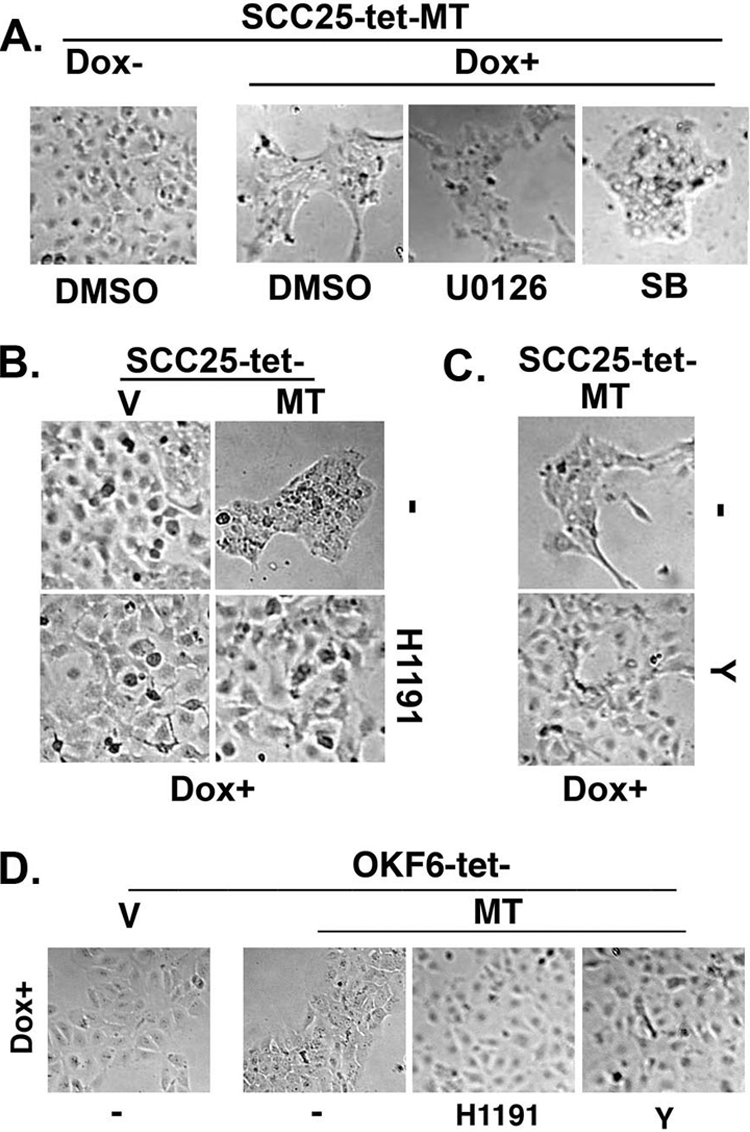

MT1-MMP-induced Cellular Aggregation Is Mediated by ROCK1/2 but Not by ERK1/2 or p38 MAPKs

In previous studies we have shown that ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs can mediate the MT1-MMP effect on MMP-2 activation (4). As a result, we next examined the role of these MAPKs in MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes in SCC and OKF6 cells using U0126 and SB202190 to block ERK1/2 or p38 MAPK activity, respectively. SCC25-tet-MT cells were treated with DMSO, U0126, or SB202190 before induction of MT1-MMP expression, and the effect on the characteristic phenotypic changes was examined 24 h later. As shown in Fig. 5A, neither U0126 nor SB202190 blocked induction of this phenotype, indicating that ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs do not play a regulatory role in mediating the phenotypic changes induced by MT1-MMP.

FIGURE 5.

MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation is mediated by ROCK1/2 but not by ERK1/2 or p38 MAPKs. A, SCC25-tet-MT cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO), MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (10 μm), or p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (SB, 10 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h. The effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microcopy. B, SCC25-tet-V (V) and SCC25-tet-MT (MT) cells were treated with ROCK1/2 inhibitor H1191 (5 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microscopy. C, SCC25-tet-MT cells were treated with ROCK1/2 inhibitor Y27632 (Y, 10 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microscopy. D, OKF6-tet-V and OKF6-tet-MT cells were treated with ROCK1/2 inhibitor H1191 (5 μm) or ROCK1/2 inhibitor Y27632 (Y, 10 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was examined by phase microscopy. The results are representative of at least four independent experiments.

In addition to the MAPK family of kinases, other candidate kinases can also regulate keratinocyte behavior (19, 20). Accordingly, we next examined the extent to which Rho signaling may be involved in mediating MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes by using two well characterized and frequently used inhibitors (H1191 and Y27632) to block the activity of the Rho-associated kinases ROCK1 and ROCK2. ROCK1 and ROCK2 are the best-characterized downstream Rho effectors (53, 54) and have been shown to play a role in the regulation of cell-cell and cell-matrix interaction (19, 20). SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-MT cells were pretreated with H1191 and co-treated with doxycycline. As previously shown in Fig. 1, induction of MT1-MMP in SCC25 cells resulted in cells moving together with increased clustering. However, in the presence of the ROCK1/2 inhibitor H1191, phenotypic changes induced by MT1-MMP were markedly diminished (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the structurally unrelated ROCK1/2 inhibitor Y27632 also abrogated the characteristic MT1-MMP phenotype (Fig. 5C). These experiments were repeated in the OKF6 model. As shown in Fig. 5D, both ROCK1/2 inhibitors also blocked the effect of MT1-MMP in this cell system, further supporting the role of Rho signaling in mediating MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes in keratinocytes. Importantly, inhibiting ROCK1/2 activity did not affect MT1-MMP protein expression in SCC25 or OKF6 cells (see the supplemental figure).

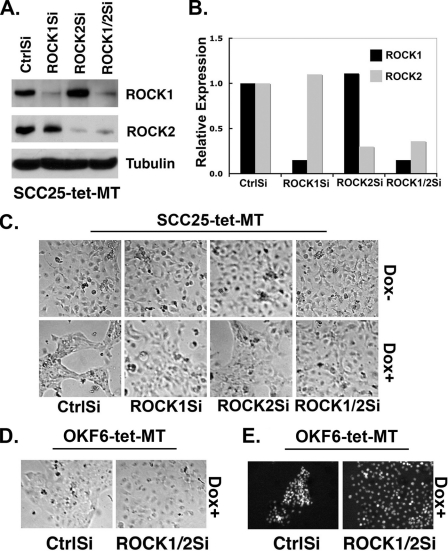

MT1-MMP-induced Cellular Aggregation Requires Both ROCK1 and ROCK2

ROCK1 and ROCK2 can differentially affect cellular behavior (55, 56), leading us to examine the specific contribution of each of the ROCK isoforms in mediating MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes. SCC25-tet-MT cells were transfected with control siRNA, ROCK1-specific siRNA, ROCK2-specific siRNA, or a 1:1 mixture of both ROCK1 and ROCK2 siRNA. The ROCK1 siRNA effectively knocked down ROCK1 expression without affecting the levels of ROCK2 protein (Fig. 6A) or mRNA (Fig. 6B). Similarly, ROCK2 siRNA effectively knocked down ROCK2 without affecting ROCK1 protein or mRNA levels (Figs. 6, A and B). After validating siRNA specificity, we examined the ability of these siRNAs to attenuate MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes (Fig. 6C). As expected, control siRNA-transfected cells demonstrated cellular aggregation and clustering after doxycycline treatment. However, transfection of ROCK1 or ROCK2 siRNA partially diminished the phenotypic changes induced by MT1-MMP, as these cells displayed only minimal clustering compared with control siRNA-treated cells. However, knocking down both ROCK1 and ROCK2 greatly attenuated the phenotypic changes seen after induction of MT1-MMP activity (Fig. 6C). Similar experiments were conducted in the OKF6-tet-MT system, including phase microscopy analysis after siRNA transfection and evaluation of internuclear distance by DAPI staining. As shown in Fig. 6D, simultaneous knockdown of ROCK1 and ROCK2 also greatly reduced the phenotypic effect induced by MT1-MMP expression, a finding that is most clearly demonstrated by comparing nuclear DAPI staining of control or siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 6E).

FIGURE 6.

MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation requires both ROCK1 and ROCK2. SCC25-tet-MT cells were transfected with control siRNA (CtrlSi), an siRNA against ROCK1 (ROCK1Si), an siRNA against ROCK2 (ROCK2Si), or a 1:1 mixture of ROCK1Si and ROCK2Si (ROCK1/2Si). A, changes in ROCK1, ROCK2, and tubulin (loading control) protein expression were examined 72 h later by Western blotting. B, the effect of these siRNAs on ROCK1, ROCK2, and GAPDH mRNA expression was determined by real-time PCR. The expression relative to GAPDH for each of the samples was normalized to the relative levels present in control siRNA transfected cells, arbitrarily set at 1.0. C, 48 h after transfection with ROCK1Si and/or ROCK2Si, the cells were treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h to induce MT1-MMP, with changes in cellular phenotype determined by phase microscopy. D and E, OKF6-tet-MT cells were transfected with control siRNA (CtrlSi) or with a 1:1 mixture of ROCK1 and ROCK2 siRNA (ROCK1/2Si). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with doxycycline for 24 h, after which the cells were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with DAPI, and changes in cellular phenotype were determined by phase and immunofluorescence microscopy. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

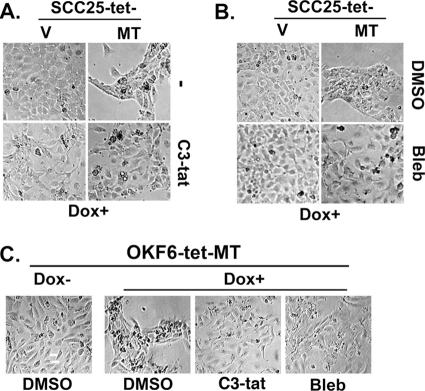

Rho and Non-muscle Myosin Mediate MT1-MMP-induced Phenotypic Changes

As ROCKI/II kinase activity can be regulated by Rho proteins (23, 54), we next examined the extent to which these small G proteins are involved in mediating MT1-MMP-induced changes in cellular phenotype. To do so, we utilized the C3 transferase toxin (C3-tat) from Clostridium botulinum, a toxin that has been shown to inhibit RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC isoforms (57). SCC25-tet-MT cells were treated with the cell permeable C3-tat, and the effect on MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes was determined. As shown in Fig. 7A, C3-tat treatment reversed to a large extent the phenotypic changes characteristically induced by MT1-MMP, indicating that the effect of MT1-MMP on cellular phenotype is mediated via Rho signaling.

FIGURE 7.

Rho and non-muscle myosin mediate MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes. A, SCC25-tet-V (V) and SCC25-tet-MT (MT) cells were treated with cell-permeable Rho A, B, C inhibitor C3-tat (1 μg/ml) and co-treated with doxycycline (Dox, 2 μg/ml) for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was determined. B, SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-MT cells were treated with non-muscle myosin inhibitor blebbistatin (Bleb, 5 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and changes in cellular phenotype were determined by phase microscopy. C, OKF6-tet-MT cells were treated with C3-tat (1 μg/ml) or non-muscle myosin inhibitor blebbistatin (5 μm) and co-treated with doxycycline for 24 h, and the effect on cellular phenotype was determined by phase microscopy. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Furthermore, we also evaluated a potential mediator downstream of ROCK1/2 that may be involved in this process. ROCK1/2 can regulate MLC phosphorylation in keratinocytes (55); thus, we conducted additional experiments in which cells were pretreated with blebbistatin, a well characterized and commonly used inhibitor of myosin II (35, 58). As shown in Fig. 7B, blebbistatin treatment markedly diminished the phenotypic effects of MT1-MMP expression. Similar findings were seen when experiments utilizing C3-tat and blebbistatin were repeated in OKF6 cells (Fig. 7C). Importantly, C3-tat and blebbistatin did not affect MT1-MMP protein expression in SCC25 or OKF6 cells (see the supplemental figure).

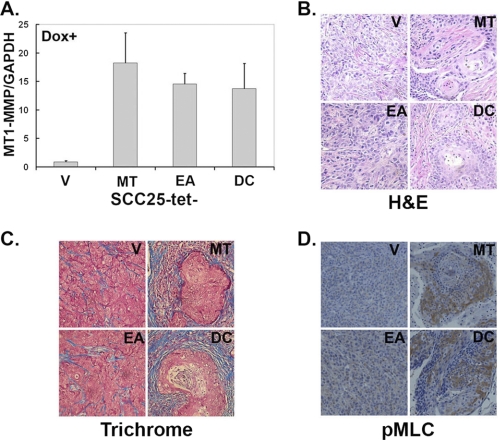

MT1-MMP Increases Cellular Aggregation and Myosin II Activity in Vivo

Finally, after identifying downstream mediators of MT1-MMP-induced phenotypic changes in vitro, we examined the consequence of inducing MT1-MMP in the in vivo microenvironment. Accordingly, SCC25-tet-V cells were injected subcutaneously on the left flank of a nude mouse, whereas SCC25-tet-MT cells were injected into the right flank of the same animal. Similarly, following the same protocol, SCC25-tet-EA cells were injected on the left with SCC25-tet-DC cells injected on the right of the same animal. Twenty-four hours later, doxycycline was added to the animals' drinking water, and the mice were monitored twice a week for tumor development. Animals were euthanized at the end of 4 weeks, and tumors were dissected and processed for histochemical staining and RNA extraction using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit. Relative to the MT1-MMP levels in SCC25-tet-V tumors, there was a 15–18-fold induction of MT1-MMP mRNA expression in the SCC25-tet-MT tumors as determined by real-time PCR (Fig. 8A). Although there was no difference in the size between the different tumors, H&E staining of tumor tissue demonstrated that SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-EA cells formed poorly demarcated tumors, whereas SCC25-tet-MT and SCC25-tet-DC cells formed well demarcated tumors with keratohyalin structures typically seen in differentiated keratinocytes (Fig. 8B) (59–61). We also examined the effect of expressing MT1-MMP in SCC cells on the surrounding stroma using trichrome stain to label the collagen present in these tumors. Consistent with previously published reports demonstrating that MT1-MMP can induce fibrosis in vivo (62, 63), SCC25-tet-MT and SCC25-tet-DC cells also induced a pronounced fibrotic reaction with increased collagen content as demonstrated by increased trichrome (blue) stain (Fig. 8C). In addition, we examined the SCC tumors for evidence of differential myosin II activity by immunostaining with anti-phospho-MLC (pMLC) antibody. In contrast to the minimal pMLC staining in the SCC25-tet-V and SCC25-tet-EA tumors, there was increased pMLC staining in the SCC25-tet-MT and SCC25-tet-DC tumors (Fig. 8D). Overall, these in vivo data provide corroborating evidence for our in vitro findings and suggest that MT1-MMP can promote cellular aggregation by increasing myosin II activity.

FIGURE 8.

MT1-MMP increases cellular aggregation and myosin II activity in vivo. Nude mice were subcutaneously injected with SCC25-tet-V (V), SCC25-tet-MT (MT), SCC25-tet-EA (EA), and SCC25-tet-DC (DC) cells as detailed under “Experimental Procedures” and maintained on doxycycline (Dox)-containing water for 4 weeks. The tumors were then excised and preserved in RNAlater or in 10% formaldehyde. A. The RNAlater-preserved tumors were processed and analyzed for human MT1-MMP and human GAPDH mRNA expression by real-time PCR. MT1-MMP expression relative to GAPDH for each of the samples was normalized to the levels present in SCC25-tet-V tumors, arbitrarily set at 1.0. B–D, the formaldehyde-fixed tumors were processed for H&E staining (B), trichrome (blue) staining to demonstrate the collagen content of the fibrotic reaction (C), and for pMLC to assess myosin II activity (D).

DISCUSSION

The proteinase MT1-MMP has been shown to be a key regulator of tumor growth and invasion in several cancer model systems. MT1-MMP directly degrades components of the ECM, thus, providing a highly regulated mechanism through which protein cleavage is localized to sites of cell-matrix contact during the process of metastasis (3, 5, 41). Importantly, genetic studies support the role of MT1-MMP as a primary regulator of interstitial collagenolysis, as mice genetically deficient in this protein have severe growth defects due to their inability to process interstitial collagens during bone formation (39, 40). Moreover, MT1-MMP expression is known to confer a three-dimensional growth advantage when expressed as part of the cellular milieu (27). In tumor cells such protease activity leads to the acquisition of invasive activity by eliminating the structural confines imposed by an intact extracellular matrix. This in turn enables the mechanical changes necessary to drive proliferative and invasive responses (27). In certain model systems including studies in prostate cancer cells (42), MT1-MMP expression has even been shown to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition, demonstrated by cells that display a more fibroblast-like, scattered growth pattern compared with controls (43). Significantly, the in vivo expression of MT1-MMP has been associated with increased SCC progression and invasion. In human SCC, MT1-MMP expression is not only up-regulated but also correlates with highly invasive and metastatic disease (64).

However, despite the clear association between MMP activity and aggressive malignant behavior, several recent studies have demonstrated a puzzling paradox; that is, MMPs can also have direct anti-tumorigenic effects (9, 10). Although provocative, the data are clear. For example, the collagenase MMP-8 can attenuate primary tumor growth and the metastatic potential of malignant cells. MMP-8 null mice develop an increased incidence of skin tumors in a carcinogen-induced model of skin cancer, a finding that is likely due to these animals' increased inflammatory response to carcinogens (65). Similarly, overexpression of MMP-8 in metastatic breast cancer cells decreases their metastatic potential (66). Of note, such findings are not unique to MMP-8. MMP-9-null mice also develop more aggressive and higher grade tumors induced by human papilloma virus 16 when compared with their wild-type control counterparts (67). As was shown with MMP-8, this effect of MMP-9 was also associated with changes in the inflammatory milieu in MMP-9-null animals. Finally, MMP-3-null mice also develop more aggressive squamous cell skin cancers compared with control animals. It is speculated that loss of MMP-3 may affect the production or function of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils (11).

Moreover, beyond their ability to inhibit tumor progression by modulating tumor inflammation, MMPs can also function in an anti-tumorigenic role by promoting tumor cell differentiation. Expression of MMP-3 using the K5 promoter to target the skin decreases the incidence of carcinogen-induced squamous cell carcinomas in treated animals (12). Interestingly, although there was no difference seen in the inflammatory response that developed in MMP-3 overexpressing animals, the resulting tumors were noted to be more differentiated with increased cellular aggregation than those seen in controls (12). Significantly, overexpression of MMP-3 targeted to the mammary epithelium causes virgin mice to phenocopy features of differentiated breast tissue normally seen only in pregnant animals, including enhanced branching, alveolar development, and production of milk protein (68–70). In this report we add to the literature dissecting the nuances of MMP function by demonstrating that MT1-MMP, a key proteinase previously shown to be critically important for cancer progression, may also play an anti-tumorigenic role by promoting keratinocyte aggregation in vitro and by inducing keratohyalin structures, which are typically seen in differentiated keratinocytes (59–61), in the in vivo microenvironment.

Our data specifically demonstrate that MT1-MMP induction in keratinocytes results in cellular aggregation, which can be attenuated by introducing additional ECM to the growth environment. In these studies we also demonstrate that the cellular aggregation induced by MT1-MMP requires functional catalytic activity of the proteinase. In turn, this suggests that the increased cell-cell aggregation observed upon MT1-MMP induction may be a secondary phenomenon after cleavage of the underlying ECM and associated decrease in cell-ECM interaction. In MMP-3-expressing papilloma cells, a similar pattern was noted in which increased keratinocyte differentiation and aggregation required MMP-3 proteolytic activity (12). Interestingly, however, as we further investigated the mechanism through which such phenotypic changes proceed, it became clear that E-cadherin, a structural protein known to mediate cell-cell interaction (16–18), is not involved in MT1-MMP-induced cellular aggregation. In contrast, the effect of MT1-MMP on cellular aggregation does seem to depend on calcium levels, as aggregation was clearly blocked under low-calcium conditions (data not shown). At this time, it is not yet clear whether the effects of low calcium result from a failure to engage cell-cell adhesion molecules other than E-cadherin or because of our previously published observation that catalytic function of MT1-MMP in keratinocytes is attenuated in low calcium conditions (30).

After clearly establishing the phenotypic consequences of MT1-MMP overexpression in keratinocytes and identifying contributing environmental factors, we next moved to determine a candidate mechanism through which such dramatic alterations in phenotype are regulated. Our findings demonstrate that the cellular aggregation induced by MT1-MMP expression involve Rho signaling pathways. Intriguingly, Rho GTPases have previously been shown to mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion (19–22). Indeed, it has been clearly established that the family of Rho proteins (RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC) play a central role in a wide array of cellular responses involving changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Strikingly, in light of our data, previous studies have shown that Rho-regulated cellular events include alterations in both epithelial shape and motility (71, 72), two processes clearly evident upon MT1-MMP overexpression in our keratinocyte model system. In our studies we also demonstrate that the phenotypic changes induced by MT1-MMP in keratinocytes involve ROCK1/ROCK2 and non-muscle myosin downstream of Rho activation. Like Rho proteins, ROCKs and non-muscle myosin have both also been shown to mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion (19–22, 73–75).

Together, such findings represent a critical new direction in MMP research precisely because of the contradictory results of previous studies attempting to translate MMP basic science into the context of human disease. Despite the overwhelming evidence that MMPs are clearly tumorigenic, clinical trials with MMP inhibitors have frustratingly failed to show any clinical benefit (10, 76). Moreover, some of these trials led to the exact opposite of the intended result as patients receiving broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors had significantly decreased survival compared with patients receiving placebo (76). Clearly, the role of MMP proteins in the tumor milieu is far more complex than previously understood. Consequently, although more specific inhibitors against particular MMPs are under development, including a blocking antibody against MT1-MMP (77), the importance of precisely defining the context in which these compounds will be used cannot be understated. Not only will it be critical to identify the right tumors to target, but defining the stage at which MT1-MMP functions as a pro-tumorigenic versus an anti-tumorigenic proteinase will also be key to the success of translational efforts involving MMPs. In light of the complex and even opposing roles played by MT1-MMP in the stepwise sequence of cancer progression, our findings may, thus, contribute to efforts to first predict and then understand potential off-target effects that may arise with the use of MT1-MMP-specific inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. M. Sharon Stack for support and encouragement throughout this project.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01CA126888 (NCI, to H. G. M.). This work was also supported by a merit grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to H. G. M.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure.

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- MT1-MMP

- membrane type 1-MMP

- SCC

- squamous cell carcinoma

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- MLC

- myosin light chain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sternlicht M. D., Werb Z. (2001) Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 17, 463–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munshi H. G., Stack M. S. (2002) Methods Cell. Biol. 69, 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbolina M. V., Stack M. S. (2008) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 24–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munshi H. G., Wu Y. I., Mukhopadhyay S., Ottaviano A. J., Sassano A., Koblinski J. E., Platanias L. C., Stack M. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39042–39050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmbeck K., Bianco P., Yamada S., Birkedal-Hansen H. (2004) J. Cell. Physiol. 200, 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radisky D. C., Levy D. D., Littlepage L. E., Liu H., Nelson C. M., Fata J. E., Leake D., Godden E. L., Albertson D. G., Nieto M. A., Werb Z., Bissell M. J. (2005) Nature 436, 123–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerkelä E., Saarialho-Kere U. (2003) Exp. Dermatol. 12, 109–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurahara S., Shinohara M., Ikebe T., Nakamura S., Beppu M., Hiraki A., Takeuchi H., Shirasuna K. (1999) Head Neck 21, 627–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Otín C., Matrisian L. M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7, 800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M. D., Matrisian L. M. (2007) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26, 717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCawley L. J., Crawford H. C., King L. E., Jr., Mudgett J., Matrisian L. M. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 6965–6972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCawley L. J., Wright J., LaFleur B. J., Crawford H. C., Matrisian L. M. (2008) Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1528–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagarajan P., Romano R. A., Sinha S. (2008) Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 18, 57–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs E. (2007) Nature 445, 834–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watt F. M., Lo Celso C., Silva-Vargas V. (2006) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16, 518–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen P. K., Bolund L. (1991) J. Cell Sci. 100, 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green H. (1977) Cell 11, 405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu A. J., Watt F. M. (1996) J. Cell Sci. 109, 3013–3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossi M., Hiou-Feige A., Tommasi Di Vignano A., Calautti E., Ostano P., Lee S., Chiorino G., Dotto G. P. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11313–11318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMullan R., Lax S., Robertson V. H., Radford D. J., Broad S., Watt F. M., Rowles A., Croft D. R., Olson M. F., Hotchin N. A. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 2185–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burridge K., Wennerberg K. (2004) Cell 116, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A. (2002) Nature 420, 629–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narumiya S., Tanji M., Ishizaki T. (2009) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 65–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villalonga P., Ridley A. J. (2006) Growth Factors 24, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braga V. M., Machesky L. M., Hall A., Hotchin N. A. (1997) J. Cell. Biol. 137, 1421–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calautti E., Grossi M., Mammucari C., Aoyama Y., Pirro M., Ono Y., Li J., Dotto G. P. (2002) J. Cell. Biol. 156, 137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotary K. B., Allen E. D., Brooks P. C., Datta N. S., Long M. W., Weiss S. J. (2003) Cell 114, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickson M. A., Hahn W. C., Ino Y., Ronfard V., Wu J. Y., Weinberg R. A., Louis D. N., Li F. P., Rheinwald J. G. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1436–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rheinwald J. G., Beckett M. A. (1981) Cancer Res. 41, 1657–1663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munshi H. G., Wu Y. I., Ariztia E. V., Stack M. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41480–41488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun L., Diamond M. E., Ottaviano A. J., Joseph M. J., Ananthanarayan V., Munshi H. G. (2008) Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond M. E., Sun L., Ottaviano A. J., Joseph M. J., Munshi H. G. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 2197–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joseph M. J., Dangi-Garimella S., Shields M. A., Diamond M. E., Sun L., Koblinski J. E., Munshi H. G. (2009) J. Cell. Biochem. 108, 726–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gospodarowicz D., Delgado D., Vlodavsky I. (1980) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 4094–4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaggioli C., Hooper S., Hidalgo-Carcedo C., Grosse R., Marshall J. F., Harrington K., Sahai E. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1392–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munshi H. G., Ghosh S., Mukhopadhyay S., Wu Y. I., Sen R., Green K. J., Stack M. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38159–38167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ottaviano A. J., Sun L., Ananthanarayanan V., Munshi H. G. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 7032–7040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmbeck K., Bianco P., Caterina J., Yamada S., Kromer M., Kuznetsov S. A., Mankani M., Robey P. G., Poole A. R., Pidoux I., Ward J. M., Birkedal-Hansen H. (1999) Cell 99, 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Z., Apte S. S., Soininen R., Cao R., Baaklini G. Y., Rauser R. W., Wang J., Cao Y., Tryggvason K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4052–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seiki M., Koshikawa N., Yana I. (2003) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 22, 129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao J., Chiarelli C., Richman O., Zarrabi K., Kozarekar P., Zucker S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6232–6240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss N. M., Liu Y., Johnson J. J., Debiase P., Jones J., Hudson L. G., Munshi H. G., Stack M. S. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 809–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rozanov D. V., Deryugina E. I., Monosov E. Z., Marchenko N. D., Strongin A. Y. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 293, 81–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Labrecque L., Nyalendo C., Langlois S., Durocher Y., Roghi C., Murphy G., Gingras D., Béliveau R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52132–52140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Alessio S., Ferrari G., Cinnante K., Scheerer W., Galloway A. C., Roses D. F., Rozanov D. V., Remacle A. G., Oh E. S., Shiryaev S. A., Strongin A. Y., Pintucci G., Mignatti P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 87–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moss N. M., Barbolina M. V., Liu Y., Sun L., Munshi H. G., Stack M. S. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 7121–7129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moss N. M., Wu Y. I., Liu Y., Munshi H. G., Stack M. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19791–19799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang A., Lehti K., Wang X., Weiss S. J., Keski-Oja J., Pei D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13693–13698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uekita T., Itoh Y., Yana I., Ohno H., Seiki M. (2001) J. Cell. Biol. 155, 1345–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baciu P. C., Suleiman E. A., Deryugina E. I., Strongin A. Y. (2003) Exp. Cell. Res. 291, 167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gálvez B. G., Matías-Román S., Yáñez-Mó M., Sánchez-Madrid F., Arroyo A. G. (2002) J. Cell. Biol. 159, 509–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sahai E., Marshall C. J. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olson M. F. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 242–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu Y., Thumkeo D., Keel J., Ishizaki T., Oshima H., Oshima M., Noda Y., Matsumura F., Taketo M. M., Narumiya S. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thumkeo D., Shimizu Y., Sakamoto S., Yamada S., Narumiya S. (2005) Genes Cells 10, 825–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aktories K., Rösener S., Blaschke U., Chhatwal G. S. (1988) Eur. J. Biochem. 172, 445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanz-Moreno V., Gadea G., Ahn J., Paterson H., Marra P., Pinner S., Sahai E., Marshall C. J. (2008) Cell 135, 510–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hennings H., Holbrook K. A. (1983) Exp. Cell. Res. 143, 127–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knight J., Gusterson B. A., Cowley G., Monaghan P. (1984) Ultrastruct. Pathol. 7, 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pillai S., Bikle D. D., Hincenbergs M., Elias P. M. (1988) J. Cell. Physiol. 134, 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ha H. Y., Moon H. B., Nam M. S., Lee J. W., Ryoo Z. Y., Lee T. H., Lee K. K., So B. J., Sato H., Seiki M., Yu D. Y. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 984–990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soulié P., Carrozzino F., Pepper M. S., Strongin A. Y., Poupon M. F., Montesano R. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1689–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimada T., Nakamura H., Yamashita K., Kawata R., Murakami Y., Fujimoto N., Sato H., Seiki M., Okada Y. (2000) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 18, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balbín M., Fueyo A., Tester A. M., Pendás A. M., Pitiot A. S., Astudillo A., Overall C. M., Shapiro S. D., López-Otín C. (2003) Nat. Genet. 35, 252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Montel V., Kleeman J., Agarwal D., Spinella D., Kawai K., Tarin D. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 1687–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coussens L. M., Tinkle C. L., Hanahan D., Werb Z. (2000) Cell 103, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alexander C. M., Selvarajan S., Mudgett J., Werb Z. (2001) J. Cell. Biol. 152, 693–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sympson C. J., Talhouk R. S., Alexander C. M., Chin J. R., Clift S. M., Bissell M. J., Werb Z. (1994) J. Cell. Biol. 125, 681–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Witty J. P., Wright J. H., Matrisian L. M. (1995) Mol. Biol. Cell. 6, 1287–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gómez del Pulgar T., Benitah S. A., Valerón P. F., Espina C., Lacal J. C. (2005) BioEssays 27, 602–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall A. (2009) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harb N., Archer T. K., Sato N. (2008) PLoS One 3, e3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martinez-Rico C., Pincet F., Thiery J. P., Dufour S. (2010) J. Cell Sci. 123, 712–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peyton S. R., Putnam A. J. (2005) J. Cell. Physiol. 204, 198–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coussens L. M., Fingleton B., Matrisian L. M. (2002) Science 295, 2387–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Devy L., Huang L., Naa L., Yanamandra N., Pieters H., Frans N., Chang E., Tao Q., Vanhove M., Lejeune A., van Gool R., Sexton D. J., Kuang G., Rank D., Hogan S., Pazmany C., Ma Y. L., Schoonbroodt S., Nixon A. E., Ladner R. C., Hoet R., Henderikx P., Tenhoor C., Rabbani S. A., Valentino M. L., Wood C. R., Dransfield D. T. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 1517–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.