Abstract

Context

Pain and depression are two of the most prevalent and treatable cancer-related symptoms, each present in at least 20-30% of oncology patients.

Objectives

To determine the associations of pain and depression with health-related quality of life (HRQL), disability, and health care use in cancer patients.

Methods

The Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) study is a randomized clinical trial comparing telecare management vs. usual care for patients with cancer-related pain and/or clinically significant depression. In this paper, baseline data on patients enrolled from 16 urban or rural community-based oncology practices are analyzed to test the associations of pain and depression with HRQL, disability, and health care use.

Results

Of the 405 participants, 32% had depression only, 24% pain only, and 44% both depression and pain. The average Hopkins Symptom Checklist 20-item (HSCL-20) depression score in the 309 depressed participants was 1.64 (on 0-4 scale), and the average Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) severity score in the 274 participants with pain was 5.2 (on 0-10 scale), representing at least moderate levels of symptom severity. Symptom-specific disability was high, with participants reporting an average of 16.8 days out of the past 28 (i.e., 60% of their days in the past four weeks) in which they were either confined to bed (5.6 days) or had to reduce their usual activities by 50% (11.2 days) due to pain or depression. Moreover, 176 (43%) reported being unable to work due to health-related reasons. Depression and pain had both individual and additive adverse associations with quality of life. Most patients were currently not receiving care from a mental health or pain specialist.

Conclusion

Depression and pain are prevalent and disabling across a wide range of types and phases of cancer, commonly co-occur, and have additive adverse effects. Enhanced detection and management of this disabling symptom dyad is warranted.

Keywords: Cancer, pain, depression, disability, quality of life, health care use

Introduction

Pain and depression are two of the most common and potentially treatable symptoms in cancer patients. Pain is present in 14-100% of cancer patients, depending upon the setting, and the prevalence of major depressive disorder is 10-25%, with a similar range for clinically depressive symptoms.1-4 These symptoms have a substantial adverse effect on functional status and quality of life5-9 and are poor prognostic factors for survival in advanced cancer10,11 including a desire for hastened death.12 Moreover, both depression and pain are frequently underdiagnosed in cancer patients,13-16 and up to half of cancer patients depressed at baseline remain depressed at one-year follow-up.1 Likewise, cancer pain often is undertreated.1,17,18

While there is considerable research on the prevalence and impact of pain and depression as individual symptoms in cancer patients, as well as their frequent co-occurrence, there have been fewer studies on the independent and additive effects of pain and depression on health-related quality-of-life (HRQL) in the same patient population. Moreover, these studies have been limited by highly selected cancer patients, small sample size, and focus on a single HRQL outcome. For example, three studies focused on a desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients; this outcome was associated with both depression and pain in one study12, but only depression in the other two studies.19,20 Three studies examined the individual associations of pain and depression with HRQL but did not examine their relative and combined effect.21-23 One study of 115 cancer survivors found differential effects of pain, depression, and other symptoms on various domains of HRQL.24

The Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) study is a clinical trial enrolling patients from community-based oncology practices who suffer from depression and/or cancer-related pain and randomizing them to telecare management or usual care. INCPAD is therefore a good study in which to study the individual and combined effects of pain and depression. Our primary hypothesis for this paper is that pain and depression in patients with cancer have independent and synergistic associations with both increased disability as well as poorer HRQL in domains not directly related to pain and mental health. Secondarily, we hypothesize that pain and depression are associated with increased health care use.

Methods

Screening and Eligibility Interview

Details of the INCPAD study methods have been previously reported. 25 Briefly, patients presenting for outpatient visits at one of 16 urban and rural participating oncology practices in the state of Indiana between March 2006 and August 2008 were invited to complete a 4-item depression and pain screener, consisting of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item (PHQ-2) depression scale and the SF-36 bodily pain scale, both of which are well-validated measures for assessing depression and pain severity.26,27 Patients who screened positive for pain (at least moderate pain severity or pain interference)27,28 or for depression (PHQ-2 score ≥2) 26 and were potentially interested in the study underwent an eligibility interview.

Depression had to be of at least moderate severity, defined as a Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) depression score of 10 or greater with either depressed mood and/or anhedonia being endorsed.29-31 In previous studies, > 90% of patients fulfilling this PHQ-9 criterion had major depression and/or dysthymia, and the remaining patients had clinically significant depression with substantial functional impairment.29,32

Pain had to be: (a) at least moderate in severity, defined as a Brief Pain Inventory score of 5 or greater;17,33-35 (b) persistent despite the use of at least two different analgesics; (c) cancer-related. Cancer-related is defined as pain occurring in the region of the primary tumor or cancer metastases and/or occurring after the onset of cancer treatment. Excluded were preexisting pain conditions unrelated to cancer (e.g., migraine or tension headache, arthritis, back disorders, bursitis/tendonitis, injuries, fibromyalgia).

Excluded were individuals who: (a) did not speak English; (b) had moderately severe cognitive impairment as defined by a validated 6-item cognitive screener;36 (c) had schizophrenia or other psychosis; (d) had a disability claim currently being adjudicated for pain; (e) had depression directly precipitated by a cancer therapy for which depression is a well-known side effect (e.g., interferon, corticosteroids) and in whom short treatment duration and tolerable depression severity justify withholding antidepressant therapy; (f) were pregnant; or (g) were in hospice care.

Study Measures

Depression diagnoses were established with the PHQ-9 which, with several added questions, categorizes individuals into three DSM-IV diagnostic subgroups: major depression, dysthymia, and other depression.29 Depression severity was assessed with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 20-item (HSCL-20) depression scale32,37,38 which had an excellent internal reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.89) in our sample. Pain was assessed primarily with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) which rates the severity of pain on four items (current, worst, least, and average pain in past week), and the interference in seven areas (mood, physical activity, work, social activity, relations with others, sleep, enjoyment of life).17,39,40 Internal reliability was also excellent for the BPI severity (α = 0.79) and BPI interference (α = 0.89) scales. The SF-36 Bodily Pain scale41 (α = 0.73) provided a secondary measure of pain.

Health-related quality of life was assessed with the SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores42(α = 0.84 for both), as well the SF-3643,44 mental health scale (α = 0.82), vitality scale (α = 0.75), and a single general health perceptions item that has shown to predict long-term health outcomes.45 Functional status, an important aspect of health-related quality of life, was further assessed with the 3-item Sheehan Disability Scale (α = 0.82) and a single-item overall quality of life measure46,47 In addition, disability days were assessed as the number of days during the preceding four weeks in which the patient was either in bed or had to reduce his or her work or usual activities by 50% or more.48,49 This total number of disability days could therefore range from 0 to 28. Anxiety severity was assessed by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale50,51 (α = 0.86) for which the score ranges from 0 to 21 and which has proven to be a good screener for the most common anxiety disorders seen in medical patients.

Medication use (antidepressants, other psychotropics, and opioid and nonopioid analgesics) was extracted from each patient's oncology practice records. Also, patients were asked in the baseline interview about treatments they had received and practitioners they had seen for depression and/or pain. Self-reported health care use in the preceding three months of five types of health services was assessed: hospital days and visits to an outpatient physician, emergency department, mental health professional, or complementary or alternative medicine (CAM) provider. Finally, in addition to gathering demographic information, medical comorbidity was assessed with a checklist of eight common medical disorders that have shown been shown to predict hospitalization and mortality.52

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the three patient groups (pain only, depression only, pain and depression) were described and bivariate comparisons were tested using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Since these bivariate comparisons were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, any differences among groups that are not highly significant (P < 0.001) should be interpreted cautiously. Depression- and pain-specific treatments were also described for the three groups without statistical comparisons.

Our primary outcomes of interest were three HRQL domains (vitality, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life) and two measures of disability (Sheehan Disability score and number of disability days). The relationship of the three HRQL outcomes and the Sheehan Disability score to pain and depression were examined in multivariable linear regression models. The relationship of total number of disability days in the preceding four weeks to pain and depression was examined in a multivariable log-linear regression model based on Poisson distribution. The dependent variable in each model was one of the HRQL or disability outcomes. The independent variables were HSCL-20 depression and BPI pain severity scores. The covariates were age, sex, race (white, other), medical comorbidity, educational level (less than high school vs. high school education or higher), income (not enough to make ends meet vs. comfortable or just enough to make ends meet), and employment status (unemployed or unable to work for health or disability reasons vs. employed, retired, homemaker, or student).

Multivariable models were run in four steps: pain only (Step 1), depression only (Step 2), pain and depression (Step 3) and pain and depression adjusting for covariates (Step 4). Steps 1 and 2 were run to explore the individual association of pain and depression with the outcomes. Step 3 aimed to determine the independent effects of pain and depression controlling for the presence of each other. Step 4 examined the independent effects of pain and depression while controlling for the effects of potential confounders. Results in the fully adjusted model (step 4) were adjusted for multiple comparisons using a modified Bonferroni procedure.53

Secondarily, we explored differences among the three symptom groups in the five patient-reported measures of health care use. Since health care use was reported in ordinal categories, group differences were compared by Chi-square and adjusted for multiple comparisons using a modified Bonferroni technique.53 All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Screening, Eligibility and Enrollment

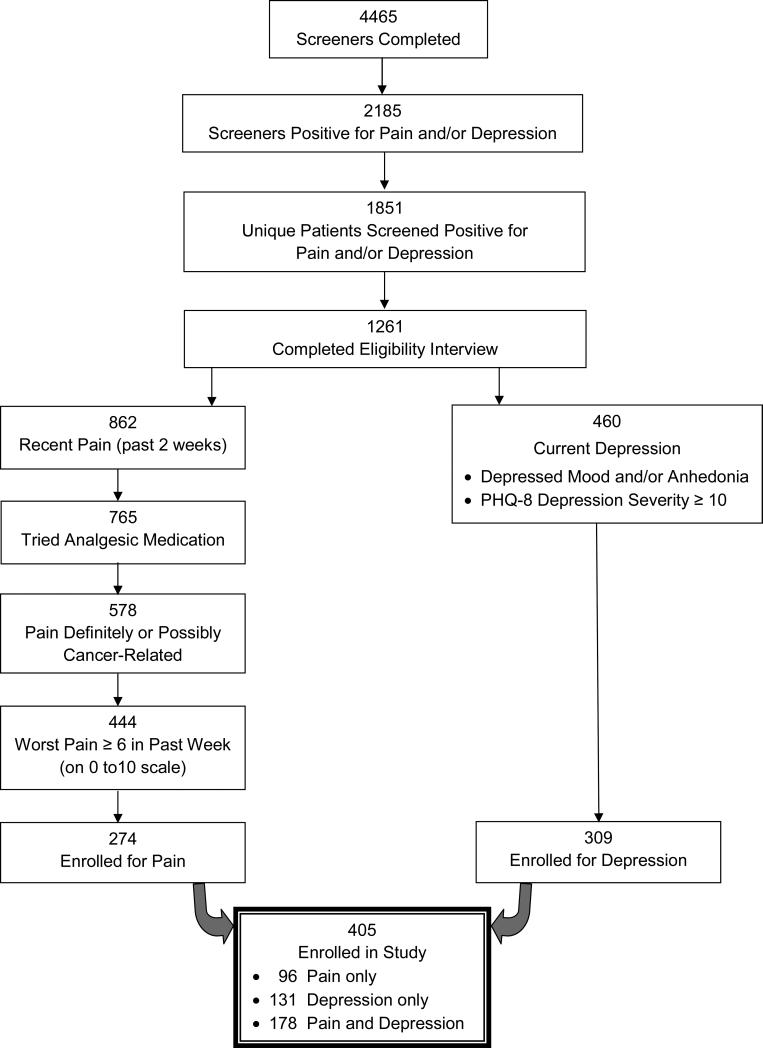

Figure 1 summarizes the participant flow in terms of screening, eligibility and enrollment. Of 4465 screening questionnaires received from the oncology clinics, nearly half (n = 2185; 48.9%) were positive for pain and/or depression. This represented 1851 unique patients who screened positive for depression and/or pain, since 334 patients had screened positive on more than one occasion. We were able to contact and complete eligibility interviews in 1261 screen-positive patients. We enrolled 274 (61.7%) of the 444 patients who met all entry criteria for pain, and 309 (67.2%) of the 460 patients who met entry criteria for depression. Our total enrolled sample was 405 patients, of whom 96 (23.7%) had pain only, 131 (32.3%) had depression only, and 178 (44.0%) had both pain and depression.

Figure.

Flow diagram of screening and enrollment of participants in INCPAD study.

Secondary Findings from Eligibility Interview

Additional questions were asked of the 578 patients whose pain was possibly cancer-related in order to better characterize pain location, duration, and severity. The location of pain was the back in 184 (31.8%), abdomen in 94 (16.3%), shoulders in 75 (13.0%), hips in 63 (10.9%), knees in 57 (9.9%), chest in 80 (13.8%), feet in 51 (8.8%), headache in 47 (8.1%), neck in 41 (7.1%), elbows or hands in 36 (6.2%), and generalized/widespread in 23 (4.0%). Pain was present in a single site in 37.7 % of patients, two sites in 36.2%, and three or more sites in 26.1%. Pain had been present less than a month in 13%, one to three months in 24%, four to 12 months in 27%, one to five years in 29%, and more than five years in 7%. The proportion of patients rating their average pain in the past week on a 0 to 10 scale as 1 to 3 (mild), 4 to 6 (moderate) and 7 to 10 (severe) was 37.4%, 55.5%, and 7.1%, respectively. However, the proportion rating their worst pain as 6 or greater (a study entry criterion) was 444 (76.8%) of the 578 patients.

Of the 1261 patients who screened positive for depression and/or pain and who completed an eligibility interview, the distribution of PHQ-8 depression scores was 0-4 (no to minimal depressive symptoms), 5 to 9 (mild), 10 to 14 (moderate), and ≥ 15 (moderately severe to severe) in 42.7%, 20.9%, 19.5%, and 16.0%, respectively. A total of 460 (36.5%) met the entry criteria for depression (PHQ-8 score ≥ 10 and either depressed mood or anhedonia).

Characteristics of the Overall Sample

Table 1 compares characteristics of the study participants across the three study groups. Overall, the 405 study participants had a mean age of 58.8 years, 68% were women, and 20% were minority (principally African-American). The type of cancer was breast in 118 (29%) of the participants, lung in 81 (20%), gastrointestinal in 70 (17%), lymphoma or hematological in 53 (13%), genitourinary in 41 (10%), and other in 42 (10%). The phase of cancer was newly-diagnosed in 150 (37%), disease-free or maintenance therapy in 172 (42%), and recurrent or progressive in 83 (21%). Medication information obtained from the oncology practice records indicated that antidepressants (excluding tricyclics) were taken by 150 (37.8%) of study participants at baseline and opioid analgesics by 214 (54.0%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 405 Subjects by Pain and Depression Group

| Baseline Characteristic | Pain Only (n = 96) | Depression Only (n = 131) | Depression and Pain (n = 178) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, yr | 60.3 (9.7) | 60.3 (11.0) | 57.0 (11.0) | 0.009 |

| Women, n (%) | 66 (68.8) | 94 (71.8) | 115 (64.6) | 0.40 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.20 | |||

| White | 72 (75.0) | 110 (84.0) | 140 (78.7) | |

| Black | 22 (22.9) | 16 (12.2) | 35 (19.7) | |

| Other | 2 (2.1) | 5 (3.8) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.34 | |||

| Less than High school | 23 (24.0) | 24 (18.3) | 40 (22.5) | |

| High school | 31 (32.3) | 63 (48.1) | 66 (37.1) | |

| Some college or trade school | 29 (30.2) | 31 (23.7) | 48 (27.0) | |

| College graduate | 13 (13.5) | 13 (9.9) | 24 (13.5) | |

| Married, n (%) | 48 (50.0) | 67 (51.2) | 77 (43.3) | 0.24 |

| Employment status, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Employed | 33 (34.4) | 22 (16.8) | 26 (14.6) | |

| Unable to work due to health or disability | 27 (28.1) | 51 (38.9) | 98 (55.1) | |

| Retired | 30 (31.3) | 48 (36.6) | 39 (21.9) | |

| Other | 6 (6.3) | 10 (7.6) | 15 (8.4) | |

| Income level, n (%) | 0.018 | |||

| Comfortable | 31 (32.3) | 32 (24.4) | 37 (20.8) | |

| Just enough to make ends meet | 50 (52.1) | 60 (45.8) | 82 (46.1) | |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 14 (12.6) | 38 (29.0) | 59 (33.2) | |

| Mean (SD) no. of medical diseases | 1.84 (1.50) | 2.05 (1.44) | 2.22 (1.76) | 0.18 |

| Type of cancer, n (%) | 0.37 | |||

| Breast | 24 (25.0) | 48 (36.6) | 46 (25.8) | |

| Lung | 18 (18.8) | 28 (21.4) | 35 (19.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 16 (16.7) | 19 (14.5) | 35 (19.7) | |

| Lymphoma and hematological | 16 (16.7) | 13 (9.9) | 24 (13.5) | |

| Genitourinary | 12 (12.5) | 14 (10.7) | 15 (8.4) | |

| Other | 10 (10.4) | 9 (6.9) | 23 (12.9) | |

| Phase of cancer, n (%) | 0.32 | |||

| Newly-diagnosed | 31 (32.3) | 46 (35.1) | 73 (41.1) | |

| Maintenance or disease-free | 40 (41.7) | 62 (47.3) | 70 (39.3) | |

| Recurrent or progressive | 25 (26.0) | 23 (17.6) | 35 (19.7) | |

| Major depression, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 71 (54.2) | 119 (66.9) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline medication use, n (%)a | ||||

| Antidepressants (excluding tricyclics) | 24 (25.3) | 56 (44.4) | 70 (40.0 ) | 0.01 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 4 (4.2) | 13 (10.3) | 18 (10.3) | 0.19 |

| Psychotropics (excluding antidepressants) | 26 (27.4) | 38 (30.2) | 51 (29.1) | 0.90 |

| Opioid analgesics | 51 (53.7) | 55 (43.7) | 108 (61.7) | 0.008 |

| Nonopioid analgesics | 43 (45.3) | 61 (48.4) | 74 (42.3) | 0.57 |

| Mean (SD) scale scores | ||||

| BPI pain severity (score range, 0-10) | 4.85 (2.03) | 2.28 (2.10) | 5.41 (1.67) | <0.0001 |

| SCL-20 depression (score range, 0-4) | 0.82 (0.56) | 1.51 (0.58) | 1.73 (0.66) | <0.0001 |

| Mean SF functional status (score range, 0-100) | ||||

| General health perceptions | 36.2 (29.0) | 32.4 (30.6) | 20.8 (24.8) | <0.0001 |

| Vitality | 41.5 (20.5) | 26.5 (17.9) | 22.4 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Mental health | 74.3 (17.2) | 50.5 (18.6) | 49.9 (20.6) | <0.0001 |

| Bodily pain | 39.2 (19.8) | 50.6 (25.1) | 27.7 (15.2) | <0.0001 |

| Physical component summary | 32.8 (9.5) | 35.9 (8.5) | 30.2 (7.9) | <0.0001 |

| Mental component summary | 50.3 (10.4) | 37.5 (11.7) | 37.4 (11.2) | <0.0001 |

| Mean Sheehan Disability (score range, 0-10) | 3.7 (2.9) | 5.5 (2.7) | 6.4 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Mean overall quality of life (score range, 0-10) | 7.1 (2.2) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.2 (2.3) | <0.0001 |

| Mean GAD-7 anxiety (score range, 0-21) | 3.7 (3.9) | 8.2 (5.5) | 9.9 (5.9) | <0.0001 |

| Mean disability days in past 4 weeks | ||||

| Bed days | 2.7 (5.0) | 5.0 (7.2) | 7.7 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Days activities reduced by ≥ 50% | 9.5 (9.7) | 11.5 (9.0) | 11.9 (8.5) | 0.096 |

| Total disability days | 12.2 (10.4) | 16.5 (10.2) | 19.6 (9.2) | <0.0001 |

Baseline medication data was available from the oncology medical records for 396 (97.8%) of the 405 participants, including 95/96 of those with pain, 126/131 of those with depression, and 175/178 of those with both pain and depression.

The 405 study participants reported an average of 16.8 days out of the past 28 (i.e., 60% of their days in the past four weeks) in which they were either confined to bed (5.6 days) or had to reduce their usual activities by 50% (11.2 days) due to pain or depression. Moreover, 176 (43%) reported being unable to work due to health-related reasons. The mean SF-12 Physical Component Summary score of 32.7 substantiates the rather severe degree of impairment, as does the mean SF-36 Vitality (28.3) and General Health Perceptions (28.2) scores.

Symptom Severity and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL)

The average SCL-20 depression score in the 309 depressed participants was 1.64 (on a 0-4 scale), and the average BPI severity score in the 274 participants with pain was 5.2 (on a 0-10 scale), representing at least moderate levels of symptom severity. As expected, the pain-specific (BPI severity, SF bodily pain) scores were higher in the pain only and depression/pain groups, while the depression/mental health-specific (SCL-20, GAD anxiety, SF Mental Component Summary) scores were higher in the depression only and depression/pain groups (Table 1). In terms of the three more generic HRQL measures (general health perceptions, vitality scores, overall quality of life), the depression-only group tended to have worse scores than the pain-only group, with the worst scores seen in the group with comorbid pain and depression.

Disability

There was an incremental increase in total disability days in the past four weeks as one went from the pain only (12.2 days) to depression only (16.5 days) to comorbid pain and depression (19.6 days) subgroups. Likewise, the proportion of patients being unable to work due to health-related reasons progressively increased among these three groups (28% vs. 39% vs. 55%), as did the Sheehan Disability Index (3.7 vs. 5.5 vs. 6.4).

Self-Reported Treatments for Pain and Depression

Table 2 summarizes the treatments patients reported taking for their pain and depression. Only a minority of patients reported receiving current care from a mental health professional or taking St. John's Wort or other herbal treatments. The majority of patients were taking a medication for their pain, whereas few reported nonpharmacological treatments. Of the 258 subjects enrolled in the study for pain who provided information on hours of relief from their pain medication, more than a third (n = 95; 36.8%) reported three hours or less of relief. Patients in the pain only group reported that pain medications relieved 69.8% of their pain, whereas patients in the pain and depression group reported 63.4% relief. While many patients with pain reported seeing a variety of specialists sometime in their lifetime for pain, few were currently going to a pain clinic (6.9% of those enrolled for pain) or receiving physical therapy, chiropractic care, massage therapy, or acupuncture. Consulting other specialists for pain was only asked in terms of lifetime use, and here the most commonly seen were orthopedics and neurology.

Table 2.

Depression and Pain-Specific Treatments Reported by Study Subjects

| Treatment | Pain Only (n = 96) | Depression Only (n = 131) | Pain and Depression (n = 178) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression treatments | N (%) | |||

| • St. John's Wort or other herbals | Ever | 9 (9.4) | 23 (17.6) | 25 (14.0) |

| • Mental health professional – | Ever | 39 (40.6) | 47 (35.9) | 83 (46.6) |

| Current | 4 (4.2) | 16 (12.2) | 24 (13.5) | |

| Pain treatments | n (%) | |||

| Pain treatments (can include more than 1) | ||||

| • Over the counter medications | 35 (36.5) | 31 (23.7) | 61 (34.3) | |

| • Prescribed medications | 71 (74.0) | 59 (45.0) | 151 (84.8) | |

| • Nonpharmacological treatments | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| • No pain treatments | 3 (3.2) | 58 (44.3) | 4 (2.3) | |

| Hours of relief from pain medicines (of 329 with analyzable data) | (n = 90) | (n = 71) | (n = 168) | |

| • 0-1 | 5 (5.6) | 10 (14.1) | 16 (9.5) | |

| • 2-3 | 17 (18.9) | 7 (9.9) | 47 (28.0) | |

| • 4 | 26 (28.9) | 15 (21.1) | 37 (22.0) | |

| • 5-12 | 36 (40.0) | 26 (36.6) | 58 (34.5) | |

| • > 12 | 6 (6.7) | 13 (18.3) | 10 (6.0) | |

| Specialists seen specifically for pain, and when | ||||

| • Pain clinic | Ever | 20 (20.8) | 17 (13.0) | 35 (19.7) |

| Current | 5 (5.2) | 4 (3.1) | 12 (6.7) | |

| • Physical therapy | Ever | 46 (47.9) | 65 (49.6) | 98 (55.1) |

| Current | 7 (7.3) | 3 (2.3) | 15 (8.4) | |

| • Chiropractor | Ever | 40 (41.7) | 58 (44.3) | 68 (38.2) |

| Current | 2 (2.1) | 3 (2.3) | 5 (2.8) | |

| • Massage therapy | Ever | 24 (25.0) | 17 (13.0) | 43 (24.2) |

| Current | 4 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | 12 (6.7) | |

| • Acupuncture | Ever | 6 (6.3) | 7 (5.3) | 9 (5.1) |

| Current | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| • Orthopedic surgeon | Ever | 32 (33.3) | 47 (35.9) | 72 (40.5) |

| • Neurologist | Ever | 28 (29.2) | 30 (22.9) | 58 (32.6) |

| • Rheumatologist | Ever | 13 (13.5) | 12 (9.2) | 31 (17.4) |

| • Another specialist for pain | Ever | 5 (5.2) | 13 (9.9) | 25 (14.0) |

| • Nonpharmacological treatments | Ever | 9 (9.4) | 14 (10.7) | 18 (10.1) |

Association of Depression and Pain with HRQoL and Disability

As noted previously, multivariable regression models were run in four steps for the each of the three generic HRQL outcomes and two disability measures. Table 3 shows the results of these four models for each dependent variable. In the final models which included both pain and depression as well as covariates and which were adjusted for multiple comparisons, depression had a strong association (P < 0.0001) with all five measures, while pain had a weaker but significant association with three measures: SF general health perceptions (P =0.049), overall quality of life (P =0.048), and total disability days in the past 4 weeks (P =0.049).

Table 3.

Association of Depression and Pain with HRQL and Disability: Results from Multivariable Regression Models

| Strength of Association of Depression (HSCL-20) and Pain (BPI) Severity with HRQL/Disabilitya | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQL or Disability Domainb | Separate Models for Depression and Pain (Steps 1 and 2) | Combined Model with both Depression and Pain (Step 3) | Combined Model Adjusted for Covariates (Step 4) | |||

| Standardized Beta or Chi-Square | P-value | Standardized Beta or Chi-Square | P-value | Standardized Beta or Chi-Square | P-valuec | |

| SF General Health Perceptions | ||||||

| • Depression | -5.45 | < 0.0001 | -5.04 | < 0.0001 | -3.97 | <0.0001 |

| • Pain | -3.82 | 0.0002 | -3.23 | 0.0013 | -2.41 | 0.049 |

| SF Vitality | ||||||

| • Depression | -14.29 | < 0.0001 | -14.22 | < 0.0001 | -14.27 | <0.0001 |

| • Pain | -1.12 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.61 | -0.43 | 0.67 |

| Quality of life, overall | ||||||

| • Depression | -10.21 | < 0.0001 | -10.53 | < 0.0001 | -9.58 | <0.0001 |

| • Pain | 1.03 | 0.30 | 2.54 | 0.012 | 2.61 | 0.048 |

| Sheehan Disability Index | ||||||

| • Depression | 12.76 | < 0.0001 | 12.42 | < 0.0001 | 11.29 | <0.0001 |

| • Pain | 3.35 | 0.0009 | 2.26 | 0.024 | 1.82 | 0.14 |

| Total disability days in past 4 weeks | ||||||

| • Depression | 433.0 | < 0.0001 | 404.3 | < 0.0001 | 302.1 | <0.0001 |

| • Pain | 37.0 | < 0.0001 | 10.3 | 0.0013 | 6.3 | 0.049 |

Association of each HRQL or disability domain with depression and pain was examined in multivariable models in 4 steps: association with depression alone (step 1) and pain alone (step 2) in separate models; with depression and pain together in combined model (step 3), and with depression and pain adjusted for covariates of age, sex, race, medical comorbidity, education, income, and employment status (step 4).

Generalized linear regression (GLM) modeling was conducted for the two SF domains, Sheehan Disability Index, and quality of life. Poisson regression modeling was conducted for total disability days. Standardized beta is beta coefficient from regression model divided by its standard error and is value reported for GLM models. Chi-square is reported for Poisson models (which is only for total disability days).

Adjusted for multiple comparisons using modified Bonferroni procedure.

Self-Reported Health Care Use

Health care use in the preceding three months is summarized in Table 4. Although it was not surprising that nearly all patients had outpatient visits, the sheer volume of visits was impressive, with 31.6% of the patients having 3-5 outpatient visits, 28.4% having 6-10 visits, and 25.6% having more than 10 visits. In terms of more costly resources, 38% of patients reported at least one hospitalization in the past three months, with the total hospital days being one to two days in 8.7% of the study sample, three to five days in 9.7%, six to 10 days in 11.6%, and more than 10 days in 7.9%. A third (33.1%) of the study patients reported at least one emergency department visit, with one of six (16.8%) reporting multiple ED visits. In contrast, a minority (17.8%) of patients reported any mental health visits during the preceding three months (defined as “psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, psychiatric nurses, or counselors”). Even among the 309 patients with depression, less than one in five (n = 61, 19.7%) had seen a mental health professional. Finally, visits to CAM providers (defined as “alternative health care providers such as chiropractors, acupuncturists, massage therapists, or others”) were rare (only 4.7% of patients). There were no significant differences among the three symptom subgroups in their use of any of the categories of health care services.

Table 4.

Patient-Reported Health Care Use in the Past 3 Months in INCPAD Participants by Pain and Depression Subgroupa

| Number of Visits or Days | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3-5 | 6-10 | > 10 | |||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Outpatient visits (n = 402) | 2 | 24 | 33 | 127 | 114 | 103 | ||||||

| Pain only (n = 95) | 0 | (0.0) | 9 | (9.5) | 10 | (10.5) | 33 | (34.7) | 26 | (27.4) | 17 | (17.9) |

| Depression only (n = 131) | 1 | (0.8) | 4 | (3.1) | 13 | (9.9) | 39 | (29.8) | 36 | (27.5) | 38 | (29.0) |

| Pain and Depression (n = 176) | 1 | (0.6) | 11 | (6.3) | 9 | (5.1) | 55 | (31.3) | 52 | (29.5) | 48 | (27.3) |

| Hospital days (n = 404) | 251 | 24 | 11 | 39 | 47 | 32 | ||||||

| Pain only (n = 96) | 62 | (64.6) | 4 | (4.2) | 4 | (4.2) | 10 | (10.4) | 9 | (9.4) | 7 | (7.3) |

| Depression only (n = 131) | 82 | (62.6) | 5 | (3.8) | 2 | (1.5) | 14 | (10.7) | 15 | (12.2) | 13 | (9.9) |

| Pain and Depression (n = 177) | 107 | (60.5) | 15 | (8.5) | 5 | (2.8) | 15 | (8.5) | 23 | (13.0) | 12 | (6.8) |

| ED visits (n = 405) | 271 | 66 | 31 | 30 | 7 | 0 | ||||||

| Pain only (n = 96) | 73 | (76.0) | 11 | (11.5) | 4 | (4.2) | 7 | (7.3) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Depression only (n = 131) | 95 | (72.5) | 18 | (13.7) | 10 | (7.6) | 6 | (4.6) | 2 | (1.5) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain and Depression (n = 178) | 103 | (57.9) | 37 | (20.8) | 17 | (9.6) | 17 | (9.6) | 4 | (2.2) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Mental health visits (n = 405) | 333 | 25 | 21 | 12 | 8 | 6 | ||||||

| Pain only (n = 96) | 85 | (88.5) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (6.3) | 2 | (2.1) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Depression only (n = 131) | 109 | (83.2) | 10 | (7.6) | 7 | (5.3) | 3 | (2.3) | 1 | (0.8) | 1 | (0.8) |

| Pain and Depression (n = 178) | 139 | (78.1) | 13 | (7.3) | 8 | (4.5) | 7 | (3.9) | 6 | (3.4) | 5 | (2.8) |

| CAM visits (n = 405) | 386 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 2 | ||||||

| Pain only (n = 96) | 92 | (95.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 2 | (2.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Depression only (n = 131) | 127 | (96.9) | 1 | (0.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.8) | 2 | (1.5) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain and Depression (n = 178) | 167 | (93.8) | 2 | (1.1) | 1 | (0.6) | 4 | (2.2) | 2 | (1.1) | 2 | (1.1) |

ED = emergency department; CAM = complementary and alternative medicine.

There were no significant differences among the 3 symptom groups for any of the 5 measures of health care use, either in unadjusted analyses or in analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons using a modified Bonferroni procedure.

Discussion

Our study has several important findings. First, of more than 4400 questionnaires administered to patients in 16 oncology practice sites, nearly half screened positive for pain and/or depression of at least moderate severity, confirming the high prevalence of these two symptoms in cancer populations.1-3 Second, pain and depression frequently co-occur and are synergistic in their association with impairment: 44% of our sample had comorbid depression and pain and this subgroup had the worst quality of life and disability. The high comorbidity of pain and depression and their reciprocal adverse effects on one another and on quality of life and functioning has been reported for cancer54-56 as well as other medical populations.57 Third, our sample experienced marked disability both in terms of profound activity limitations (i.e., an average of 60% of days in the past four weeks spent either in bed or with activities reduced by at least 50%) as well as 43% reporting unemployment due to health reasons. Fourth, our sample had substantial health care use but a low use of specialty care for depression and pain, meaning that the oncologist and/or patient's primary care physician are the de facto principal provider of symptom-based care for cancer patients.

The distribution of cancer type and phase was similar among our three patient groups (i.e., pain only, depression only, and comorbid pain and depression). Previous research has shown that depression and other psychological symptoms are prevalent regardless of site of cancer9 and vary more by prognosis, disease burden and other factors rather than specific type of cancer.58 Likewise, pain was distributed across the spectrum of cancer phases from newly diagnosed to maintenance/disease-free to recurrent or progressive. Thus, general screening for pain and depression in oncology practice is probably warranted rather than a narrow focus on certain subgroups of cancer patients.

The first step to better management of cancer-related symptoms is increased detection. The depression screener used in our study was the PHQ-2 which screens for the two core symptoms of depressive disorders, i.e., depressed mood and anhedonia.26 Ultra-brief screeners have been validated for depression in general,59, including in cancer patients.60 Also, ultra-brief screeners ranging from one to three items are validated for pain.61 However, patients and physicians often expect the other party to initiate discussions about symptoms and quality of life issues62 Therefore, educating physicians to ask about pain, depression, and other cancer symptoms as well as coaching and empowering patients to report such symptoms is essential.

Depression and pain had moderate to strong associations with impairment across multiple domains of quality of life and functional status. Depression tended to have somewhat stronger effects than pain, and depression-pain comorbidity yielded the greatest impairment. The relationship between symptom burden and quality of life in cancer patients has been noted,6 as has the particularly strong effects of depression.63,64 The frequent co-occurrence of pain-depression (45% in our sample) and their additive adverse effects make them an especially pernicious symptom dyad.21 Indeed, the clustering of cancer symptoms has attracted increasing attention, with pain, depression, and fatigue being a particularly triangulated cluster56,65

Beyond a simple decrement in quality of life and functional status, our study demonstrated a considerable degree of frank disability. Patients reported more than 60% of their days in bed or with marked reductions in activity as well as a 43% health-related unemployment rate. Apart from cancer, depression and pain are two of the most common causes of decreased work productivity.66,67 A recent meta-analysis showed the unemployment rate in cancer patients to be more than twice that of controls (34% vs. 15%).68 Thus, one would expect that adding depression and/or pain to the already disabling effects of cancer itself would be especially deleterious. At the same time, cancer patients experience substantial barriers to obtaining disability benefits.69

Health care use did not differ by symptom group in our study. The considerable amount of health care use in our study exemplifies the high financial burdens associated with cancer care which includes not only direct medical expenses70 but also indirect costs such as out-of-pocket expenditures71 as well as patient and caregiver time.72 The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that the total direct medical costs associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment in the United States in 2004 was $72.1 billion, while the indirect costs were even larger at $118 billion.73 Despite high health care use by patients in our trial, their self-reported treatments suggested a rather low rate of treatments specific to depression and pain, including only a small proportion of patients accessing mental health or pain specialists, and many patients reporting insufficient relief from pain medications. This suggests that oncology services may continue to focus principally on treatment of the cancer itself with much less attention paid to symptoms that accompany the cancer or its treatment. While some patients may access complementary and alternative medicine care, CAM was used by only a fraction of our patients and nationally accounts for only a small percent of cancer expenditures.74

Once detected, pain and depression must be effectively treated. Approaches for managing cancer-related pain include evidence-based analgesic algorithms,75 patient education,76,77 and coaching,78 improving clinician knowledge and attitudes,79-81 addressing patient and clinician misconceptions about cancer pain and its treatment,82-84 and increasing patient adherence.85 Regarding depression and other psychological conditions, there is modest evidence for pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions,86-89 though more definitive evidence from larger clinical trials is needed.90 Among psychotherapeutic interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy91 and problem-solving therapy92 seem particularly promising. Given the context and competing demands of busy oncology practices, collaborative care interventions, which have consistently proven effective for depression in general medical settings,93 might be an efficient strategy for cancer-related symptom management. Indeed, a collaborative telecare management approach covering multiple oncology practices is the focus of our present trial.25

Our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of our data prevents us from establishing a causal effect of depression and pain on the substantial functional impairment, decreased quality of life, and high health care use found in our study participants. However, there is considerable evidence that depression and pain individually do worsen these health outcomes, and that in combination have additive ill effects.21,55,57 Second, INCPAD enrolled a broad range of patients both by type and phase of cancer. This is a study strength in terms of generalizability to oncology practice but limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions about depression and pain in any one type or phase of cancer. Third, most data was obtained by patient self-report, which is the criterion standard for symptoms such as depression and pain as well as functional status and quality of life domains, but may be less desirable for health care use. The latter is available from automated records in large integrated health care systems but is not feasibly obtained in a statewide trial like INCPAD that involves individual rural as well as urban community-based oncology practices. Self-report correlates reasonably well with actual health care use94 and has been relied upon in previous community-based depression trials.95 While it may introduce some measurement imprecision into absolute rates of health care use, it is less likely to bias between-group comparisons.

In summary, depression and pain are prevalent across a wide range of cancer types and phases and are associated with increased disability and diminished HRQL. Compared to pain, depression tends to have a somewhat greater as well as more pervasive effect across multiple domains. This may be due to a number of factors ranging from depression being especially impairing to it being less readily recognized or treated by oncologists to greater reluctance by patients to accept a depression diagnosis or treatment. The frequent co-occurrence of depression and pain as well as their additive effects in several domains suggests that the detection of one symptom should trigger inquiry about the other. Our INCPAD trial will address the degree to which impairment is reduced by the comanagement of pain and depression.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the care management provided by Becky Sanders and Susan Schlundt, the project coordination by Kelli Norton, and the research assistance of Stephanie McCalley and Pam Harvey.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Kroenke (R01 CA-115369).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carr D, Goudas L, Lawrence D, et al. Management of cancer symptoms: Pain, depression, and fatigue. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2002. AHRQ Publication No. 02-E032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottomley A. Depression in cancer patients: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care. 1998;7:181–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;82:263–274. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353:1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Given CW, Given B, Azzouz F, Kozachik S, Stommel M. Predictors of pain and fatigue in the year following diagnosis among elderly cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:456–466. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Given CW, Given BA, Stommel M. The impact of age, treatment, and symptoms on the physical and mental health of cancer patients. A longitudinal perspective. Cancer. 1994;74:2128–2138. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2128::aid-cncr2820741721>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with colorectal cancer: a longitudinal view. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:494–501. doi: 10.1007/s00520-001-0338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Physical functioning and depression among older persons with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:11–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.91004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. The influence of symptoms, age, comorbidity and cancer site on physical functioning and mental health of geriatric women patients. Women Health. 1999;29:1–12. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stommel M, Given BA, Given CW. Depression and functional status as predictors of death among cancer patients. Cancer. 2002;94:2719–2727. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gripp S, Moeller S, Bolke E, et al. Survival prediction in terminally ill cancer patients by clinical estimates, laboratory tests, and self-rated anxiety and depression. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3313–3320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Galanos A, Vlahos L. The role of physical and psychological symptoms in desire for death: a study of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15:355–360. doi: 10.1002/pon.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardman A, Maguire P, Crowther D. The recognition of psychiatric morbidity on a medical oncology ward. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–1015. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, et al. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1594–1600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, et al. Major depression in outpatients attending a regional cancer centre: screening and unmet treatment needs. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:314–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:592–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleeland CS. Undertreatment of cancer pain in elderly patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1914–1915. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mystakidou K, Rosenfeld B, Parpa E, et al. Desire for death near the end of life: the role of depression, anxiety and pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahony SO, Goulet J, Kornblith A, et al. Desire for hastened death, cancer pain and depression: report of a longitudinal observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavoli A, Montazeri A, Roshan R, Tavoli Z, Melyani M. Depression and quality of life in cancer patients with and without pain: the role of pain beliefs. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lidgren M, Wilking N, Jonsson B, Rehnberg C. Health related quality of life in different states of breast cancer. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:1073–1081. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So WK, Marsh G, Ling WM, et al. The symptom cluster of fatigue, pain, anxiety, and depression and the effect on the quality of life of women receiving treatment for breast cancer: a multicenter study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;26:205–214. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E205-E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira KA, Kimura M, Teixeira MJ, et al. Impact of cancer-related symptom synergisms on health-related quality of life and performance status. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Norton K, et al. Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) Trial: design of a telecare management intervention for cancer-related symptoms and baseline characteristics of enrolled participants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user's manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, et al. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:17–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106883.94059.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, et al. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA. 2003;290:215–221. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, et al. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2947–2955. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleeland CS. Pain assessment in cancer. In: Osoba D, editor. Effect of cancer on quality of life. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams LS, Jones WJ, Shen J, Robinson RL, Kroenke K. Outcomes of newly referred neurology outpatients with depression and pain. Neurology. 2004;63:674–677. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134669.05005.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bair MJ, Williams LS, Kroenke K. Association of the ‘5th vital sign’ (pain) and depression in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 April;19:123–124. AU: COULD NOT FIND THIS IN PUBMED; PLS ADVISE. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. A six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CR, Loeser JD, editors. Issues in pain measurement. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Raven Press; New York: 1989. pp. 391–403. AU: CHANGE IN REF OKAY WITH YOU? [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams LS, Jones WJ, Shen J, et al. Prevalence and impact of pain and depression in neurology outpatients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1587–1589. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Von Korff M, Jensen MP, Karoly P. Assessing global pain severity by self-report in clinical and health services research. Spine. 2000;25:3140–3151. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware JE, Gandek B. The SF-36 Health Survey: development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA Project. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unutzer J, Williams JW, Callahan CM, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001;39:785–799. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner EH, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Hecht JA. Responsiveness of health status measures to change among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Werner J, Duan N. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins AJ, Kroenke K, Unutzer J, et al. Common comorbidity scales were similar in their ability to predict health care costs and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciaramella A, Poli P. Assessment of depression among cancer patients: the role of pain, cancer type and treatment. Psychooncology. 2001;10:156–165. doi: 10.1002/pon.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMillan SC, Tofthagen C, Morgan MA. Relationships among pain, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in outpatients from a comprehensive cancer center. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:603–611. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.603-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell AJ, Coyne JC. Do ultra-short screening instruments accurately detect depression in primary care? A pooled analysis and meta-analysis of 22 studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:144–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell AJ. Are one or two simple questions sufficient to detect depression in cancer and palliative care? A Bayesian meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1934–1943. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, Muller M, Schornagel JH. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3295–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pinquart M, Koch A, Eberhardt B, et al. Associations of functional status and depressive symptoms with health-related quality of life in cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1565–1570. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wedding U, Koch A, Rohrig B, et al. Depression and functional impairment independently contribute to decreased quality of life in cancer patients prior to chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:56–62. doi: 10.1080/02841860701460541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miaskowski C, Aouizerat BE, Dodd M, Cooper B. Conceptual issues in symptom clusters research and their implications for quality-of-life assessment in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007:39–46. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA. 2003;289:3135–3144. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443–2454. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajarvi A, van Dijk FJ, Verbeek JH. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301:753–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson K, Amir Z. Cancer and disability benefits: a synthesis of qualitative findings on advice and support. Psychooncology. 2008;17:421–429. doi: 10.1002/pon.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML. Costs of cancer care in the USA: a descriptive review. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:643–656. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, et al. Out-of-pocket health-care expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value Health. 2004;7:186–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.72334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yabroff KR, Davis WW, Lamont EB, et al. Patient time costs associated with cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:14–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lipscomb J. Estimating the cost of cancer care in the United States: a work very much in progress. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:607–610. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Devlin SM, Andersen MR, Diehr PK. Complementary and alternative medicine provider use and expenditures by cancer treatment phase. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:326–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du Pen SL, Du Pen AR, Polissar N, et al. Implementing guidelines for cancer pain management: results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:361–370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Wit R, van Dam F, Zandbelt L, et al. A pain education program for chronic cancer pain patients: follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 1997;73:55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oliver JW, Kravitz RL, Kaplan SH, Meyers FJ. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2206–2212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elliott TE, Murray DM, Elliott BA, et al. Physician knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a survey from the Minnesota cancer pain project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:494–504. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00100-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fife BL, Irick N, Painter JD. A comparative study of the attitudes of physicians and nurses toward the management of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:132–139. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Pandya KJ. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management. A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:121–126. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Riddell A, Fitch MI. Patients’ knowledge of and attitudes toward the management of cancer pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:1775–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:358–368. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomason TE, McCune JS, Bernard SA, et al. Cancer pain survey: patient-centered issues in control. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miaskowski C, Dodd MJ, West C, et al. Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: a significant barrier to effective cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4275–4279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Compas BE, Haaga DA, Keefe FJ, Leitenberg H, Williams DA. Sampling of empirically supported psychological treatments from health psychology: smoking, chronic pain, cancer, and bulimia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:89–112. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Daniels J, Kissane DW. Psychosocial interventions for cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:367–371. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283021658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodin G, Lloyd N, Katz M, et al. The treatment of depression in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:123–136. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jacobsen PB, Jim HS. Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: achievements and challenges. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:214–230. doi: 10.3322/CA.2008.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams S, Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:372–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372:40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams JW, Jr., Gerrity M, Holsinger T, et al. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cleary PD, Jette AM. The validity of self-reported physician utilization measures. Med Care. 1984;22:796–803. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rost K, Pyne JM, Dickinson LM, LoSasso AT. Cost-effectiveness of enhancing primary care depression management on an ongoing basis. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:7–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]