Abstract

In this study, the expression patterns of zif268 and arc were investigated in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and dorsal hippocampal (dHPC) subregions during context-induced drug-seeking following 22 h or 15 d abstinence from cocaine self-administration. Arc and zif/268 mRNA in BLA and dHPC increased after re-exposure to the cocaine-paired chamber at both timepoints; however, only the BLA increases (with one exception-see below) were differentially affected by the presence or absence of the cocaine-paired lever in the chamber. Following 22 h of abstinence, arc mRNA was significantly increased in the BLA of cocaine-treated rats re-exposed to the chamber only with levers extended whereas following 15 d of abstinence, arc mRNA in the BLA was increased in cocaine-treated rats returned to the chamber with or without levers extended. In contrast, zif268 mRNA in the BLA was greater in cocaine-treated rats returned to the chamber with levers extended vs. levers retracted only after 15 d of abstinence. In the dentate gyrus following 22 h of abstinence, zif268 mRNA was greater in rats returned to the chamber where levers were absent regardless of drug treatment whereas arc mRNA was increased in CA1 (cell bodies and dendrites) and CA3 only in cocaine-treated groups. Following 15d of abstinence, arc mRNA was significantly greater in CA1 and CA3 of both cocaine-treated groups returned to the chamber than in those placed into a familiar, non-salient alternate environment; however, only in CA1 cell bodies were these cocaine context-induced increases significantly greater than in yoked-saline controls. In contrast, zif/268 mRNA in all dHPC regions was significantly greater in both cocaine-treated groups returned to the cocaine context than in the cocaine-treated group returned to an alternative environment or saline-treated groups. These data suggest that the temporal dynamics of arc and zif268 gene expression in the BLA and dHPC encode different key elements of drug context-induced cocaine-seeking.

Keywords: addiction, arc, cocaine, zif268, self-administration, in situ hybridization

Drug-seeking often depends on learned associations formed between drug-paired environmental stimuli and the rewarding effects of the drug. Memory for these drug-paired cues can be highly resistant to extinction and can trigger a conditioned physiological response and a desire for the drug when encountered by abstinent individuals (Ehrman et al. 1992; O'Brien et al. 1998). Similarly, a cocaine-paired context and discrete conditioned stimuli can elicit drug-seeking behavior in rodents (Meil and See, 1996; Crombag and Shaham, 2002). Thus, memories activated by stimuli previously associated with cocaine self-administration are critical to the persistence of addiction.

Accumulating evidence from animal models of drug-seeking suggests that the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) and basolateral amygdala (BLA) form part of the neural circuitry that mediates drug context-induced cocaine-seeking behavior (Fuchs et al. 2005, 2009; Ramirez et al. 2009). In general, the hippocampus appears central to the formation and retrieval of contextual associations, while the BLA is activated by both context and discrete cues (Neisewander et al. 2000) and is important for both the initial acquisition and the expression of drug-cue conditioning that plays an important role in drug-seeking (Grimm and See, 2000; Kruzich and See, 2001; McLaughlin and See, 2003). Human imaging studies in cocaine addicts have shown that craving induced by cocaine paired cues is accompanied by increased blood flow or metabolic activity within brain regions implicated in memory, including the amygdala (Childress et al. 1999; Grant et al. 1996; Kilts et al. 2001) and hippocampus (Kilts et al. 2001). Similarly, cocaine-associated cues or a priming injection of cocaine produces changes in the pattern of activity in the amygdala and hippocampus of drug-seeking rats as measured by increased Fos (Neisewander et al. 2000). Moreover, inactivation of the dHPC or BLA disrupts context-driven reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats (Fuchs et al. 2005). However, the BLA, but not the dHPC, is critical for explicit conditioned stimulus-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (McLaughlin and See, 2003; Fuchs et al. 2005). Collectively, these data suggest that differences exist in how these brain regions contribute to drug-seeking driven by environmental stimuli.

Exposure to drugs of abuse leads to short- and long-term adaptive changes in the brain, many of which involve the regulation of gene expression. Activity-regulated immediate early genes (IEGs), such as zif268, and activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated gene (arc) are transiently induced by cocaine-associated stimuli (Everitt and Robbins, 2000; Zavala et al. 2008; Hearing et al. 2008a,b) and have been implicated in mediating cellular events that underlie drug-associated learning processes (Lee et al. 2005, 2006; Hearing et al. 2008a,b; Zavala et al. 2008), providing a molecular bridge between cocaine-induced neuroadaptations and enduring drug-seeking behavior (Nestler et al. 1993; Berke and Hyman, 2000; Nestler, 2001).

In the present study, alterations in zif268 and arc mRNA expression were used to identify activation of the dHPC and BLA in response to a cocaine-associated context following short and extended periods of abstinence after chronic cocaine self-administration. To determine whether changes in gene expression are correlated with instrumental behavior and to better isolate the effects of context-recognition on gene expression, rats were tested with levers either presented or retracted for the duration of context testing. Further, we evaluated whether differences exist in hippocampal and amygdala activity in response to processing situationally remote versus recent/familiar contextual information in rats re-exposed to the self-administration chamber.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Subjects

Male, Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), weighing 300-325 g at the start of the experiment, were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium on a reversed light/dark cycle. Rats received ~25 g of rat chow per day, which maintained them at approximately 90% of free feeding body weight, and were allowed water ad libitum. The housing and treatment of the rats was carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23, revised 1996). Formal approval to conduct the experiments was obtained from the MUSC IACUC. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Rats were given five days to adapt before the start of the experiment.

Experimental design

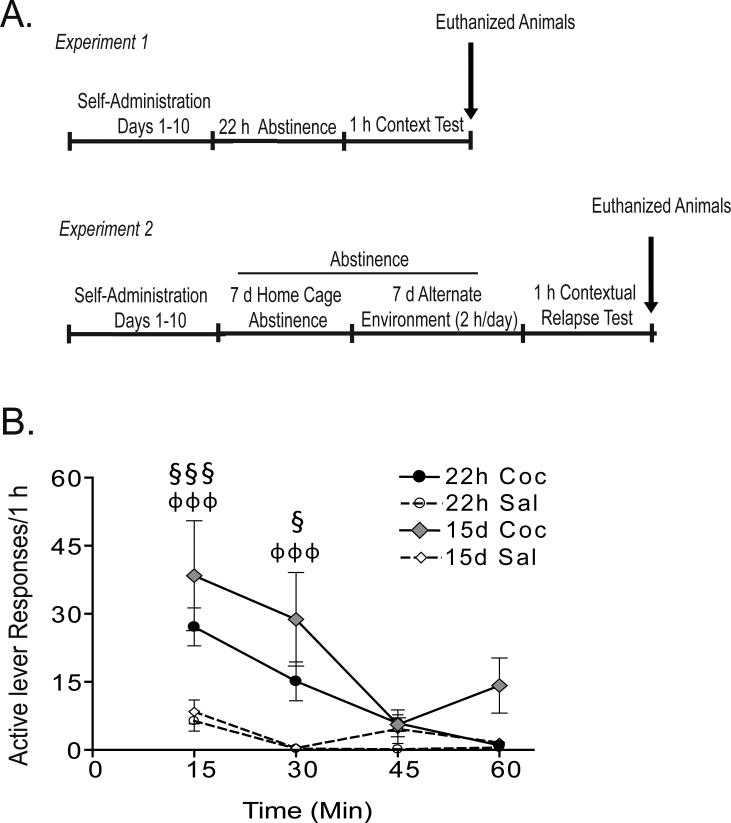

Details of the self-administration and cocaine-seeking methodology have been previously described (Hearing et al. 2008a, b) for the cohort of rats in experiments 1 and 2 from which the in situ hybridization data in this publication was derived (see Figure 1). Only essential behavioral information is provided below to facilitate understanding of the experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and active lever pressing during 1 h context-induced test of drug-seeking. (A) Schematic representing the experimental design for experiment 1 and 2 (adapted from Hearing et al. 2008). SA and CA rats were not included in the design of experiment 1 because exposure to an alternate environment on day 1 of abstinence would have constituted a novel experience. In experiment 2, all rats were habituated to the alternate environment before the test day. (B) Mean number of active lever presses in the 1 h test following 22 h and 15 d of abstinence expressed in 15 min time bins. §p<0.05, §§§p<.001 22 h cocaine vs saline; ΦΦΦp<.001 15 d cocaine vs saline.

Self-administration

One week after jugular catheter surgery, rats were trained to lever press on a fixed ratio 1 schedule of food reinforcement (45 mg pellets; Noyes, Lancaster, NH) in self-administration chambers (30 × 20 × 24 cm high; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) during a 16 hr overnight training session. The chambers were equipped with two retractable levers, a food pellet dispenser, and a house light on the wall opposite to the levers. During the session, each active lever press resulted in delivery of a food pellet only. Lever presses on the inactive lever had no programmed consequences. After lever training, pellet dispensers were removed from the chambers. Self-administration was conducted in 2 h sessions on consecutive days during the rats’ dark cycle and continued until the rats self-administered a minimum of 10 infusions per session for a minimum of 10 days (maintenance criteria). Rats responded on a fixed ratio 1 schedule of cocaine reinforcement (cocaine hydrochloride; 0.2 mg in 50 μl of sterile saline; National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Triangle Park, NC). Active lever pressing resulted in a 2 s activation of the infusion pump only. After each infusion, responses on the active lever had no consequences during a 20 s timeout period. Responses on the inactive lever had no programmed consequences. Yoked rats received infusions of saline (50 μl) contingent upon the cocaine infusions received by the animal in the adjacent chamber. Data collection and reinforcer delivery was controlled using MedPC software version IV (Med Associates).

Abstinence and drug-seeking

After the last day of self-administration, rats were returned to the colony room for 22 h (n=32) or 15 days (n=30). In experiment 2, on post-cocaine days 8-14, all rats were transported to a separate procedure room (alternate environment) that was distinctly different from the self-administration room and were placed into clear plastic holding chambers, with no stimuli or cues present, for 2 h/day. On post-cocaine day 15, rats were returned to one of the following environments: the alternate environment (SA or CA), the self-administration chamber with no levers available (SN or CN) or the self-administration chamber with the levers available (SL or CL) for 1 h. The number of lever presses for the latter group was recorded, but had no scheduled consequences. We included the alternate environment group in order to distinguish the impact of recent contextual familiarity from remote familiarity (dishabituation) when rats are re-exposed to the self-administration chamber without extinguishing the motivational effects of the cocaine-paired environment (Fuchs et al. 2006). The similar transport procedures and temporal pattern used for the alternate environment and the self-administration environment also controlled for general handling and arousal. Following the 1 h test, the rats were anesthetized with Equithesin and decapitated. Brains were rapidly frozen in dry ice-cooled isopentane (-40°C) and stored at -80°C until sectioning.

In situ hybridization histochemistry

In situ hybridization histochemistry was performed as described previously using antisense 35S-labelled oligodeoxynucleotide probes complementary to rat zif268 and arc mRNA (Hearing et al. 2008a,b). Briefly, 48 mer oligodeoxynucleotide probes ([Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Coralville, IN) were labeled using alpha-[35S]-dATP (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Roche Diagnostics Corp, Indianapolis, IN). Frozen 12 μm sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, pretreated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in sterile 0.1 M triethanolamine/0.9% NaCl pH 8.0 to reduce nonspecific binding and defatted in an ascending alcohol series followed by chloroform and a descending alcohol series, then hybridized at 37°C for 20 h. After stringent washes, slides were dried and placed in an X-ray film cassette along with 14C standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St Louis, MO) and Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Films were developed at several time points in order to establish linearity and an optimal signal to noise ratio.

Image analysis

Film autoradiograms were quantified using the Macintosh-based NIH Image program as previously described (Wang and McGinty, 1995). The mean density and number of pixels per area was measured in the selected brain regions from three adjacent sections per brain. The measurements were expressed as integrated density (# of pixels per area × mean density).

Statistical analysis

Active lever pressing in 15 min time bins during the 1 h context re-exposure following 22 h and 15 d abstinence was analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA (drug treatment × time). Statistically significant interaction effects were further investigated using Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) tests with the α set at 0.05. All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficients between the number of lever presses during the 1 h test and gene expression in the CL groups in experiments 1 and 2 were determined by a simple regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 4.

Measurements of the hybridization signals (Integrated Density) are strongly correlated and cannot be treated independently. To account for this correlation, the data was fit with a hierarchical linear model using Integrated Density as the response variable with treatment and environment (as well as a treatment by environment interaction) as fixed effects explanatory variables and rat as a random effect (mixed model SAS 9.1) followed by planned multiple comparison tests [Tukey-Kramer test (where less than 4 pairwise comparisons are made) or a Bonferonni correction (where more than 4 pairwise comparisons are made)] when an interaction is found or to further analyze the source of main effects.

RESULTS

Self-administration and cocaine-seeking after abstinence

The behavioral data were published previously (Hearing et al., 2008a). There were no significant differences between groups for lever responses for cocaine or cumulative total cocaine intake over the last 3 days of 2 h self-administration sessions in experiment 1 and experiment 2. Re-exposure to the cocaine-paired environment in the absence of cocaine reinforcement resulted in robust active lever pressing in animals with a cocaine history that was significantly higher than yoked-saline responding in both the 22 h and 15 d abstinence groups. Figure 1B illustrates the results of further analysis of active lever responses in cocaine- and yoked-saline-treated rats during the 1 h contextual drug-seeking test (15 min bins) following 22 h and 15 d abstinence. Twoway repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant interaction between drug treatment (cocaine, saline) and time (15, 30, 45, and 60 min; F(3,103)=4.59, p<.001). Subsequent multiple comparisons revealed that the mean number of active lever responses in cocaine-treated rats was significantly greater in the first two 15 min time bins compared to saline controls in both the 22 h and 15 d abstinence groups.

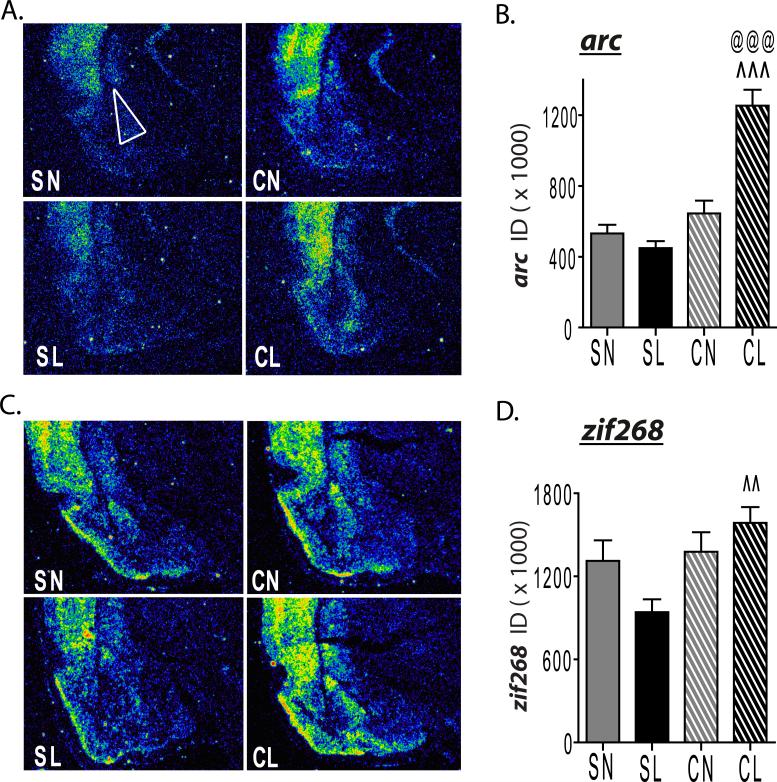

Gene expression in the BLA following 22 h of abstinence

Twenty-two h after the end of cocaine or yoked-saline sessions, arc and zif268 mRNA expression was increased in the BLA of cocaine-treated rats that were tested with the levers available relative to their respective yoked-saline controls (Figure 2). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of drug-treatment (cocaine, saline) and test environment (levers, no levers) for arc (F(1,23)=25.22, p<0.0001) and zif268 (F(1,24)=5.29, p<0.05). Multiple comparison tests showed that arc mRNA was selectively increased in the BLA of cocaine-treated rats re-exposed to the operant chamber with levers extended (CL) compared to cocaine rats without levers (CN) and yoked-saline rats with levers available (SL), whereas zif268 mRNA was greater in the CL than in the SL group only.

Figure 2.

After 22 h of abstinence, arc and zif268 mRNA in the BLA of cocaine-treated rats with access to the levers was increased during context re-exposure. Representative coronal hemi-sections illustrating the expression pattern and quantitative analysis of the integrated density of the hybridization signal for arc (A, B) and zif268 (C, D) mRNA in the BLA. Region of interest selected for measurement (white outline) in the BLA is indicated. @@@p<0.001 vs. CN; ^^p<0.01, ^^^p<0.001 vs. SL. SN, saline-no levers; SL, saline-levers available; CN, cocaine-no levers; CL, cocaine-levers available; BLA, basolateral amygdala; ID, integrated density.

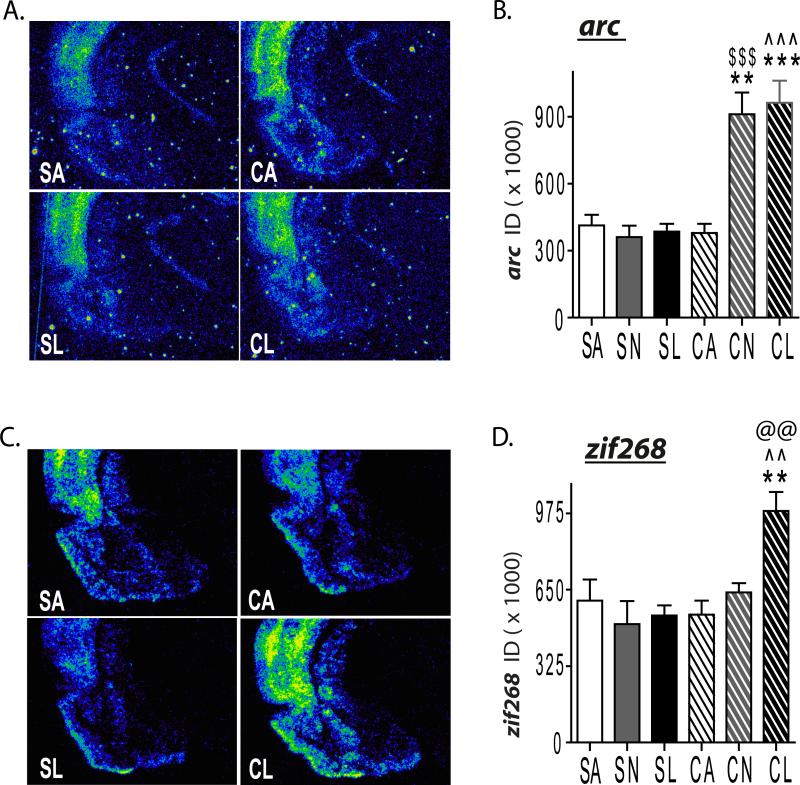

Gene expression in the BLA following 15 d of abstinence

Following 15 d of abstinence from cocaine or yoked-saline administration, re-exposure to the cocaine-paired chamber increased arc and zif268 mRNA differentially (Figure 3). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between drug treatment (cocaine, saline) and test environment (levers available, no levers available, alternate environment) for both arc (F(2,18)=22.44, p<0.0001) and zif268 (F(2,22)=6.57, p<0.01) mRNA. Multiple comparison tests revealed significantly greater arc mRNA in CN and CL groups compared to SN and SL rats respectively, as well as rats with a cocaine history placed in the alternate environment during testing (CA). In contrast, zif268 mRNA was increased in CL rats compared to CN, CA, and SL rats.

Figure 3.

After 15 d of abstinence, arc and zif268 mRNA in the BLA was increased differentially, depending on lever availability during 1 h re-exposure to the cocaine-paired context. Representative coronal hemi-sections illustrating the expression pattern and quantitative analysis of the integrated density of the hybridization signal for arc (A,B) and zif268 (C,D) in the BLA. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. CA; @@p<0.01 vs. CN; ^^p<0.01, ^^^p<0.001 vs. SL; $$$p<0.001 vs. SN. SA, saline-alternate environment; CA, cocaine-alternate environment; SN, saline-no levers; SL, saline-levers available; CN, cocaine-no levers; CL, cocaine-levers available; BLA, basolateral amygdala; ID, integrated density.

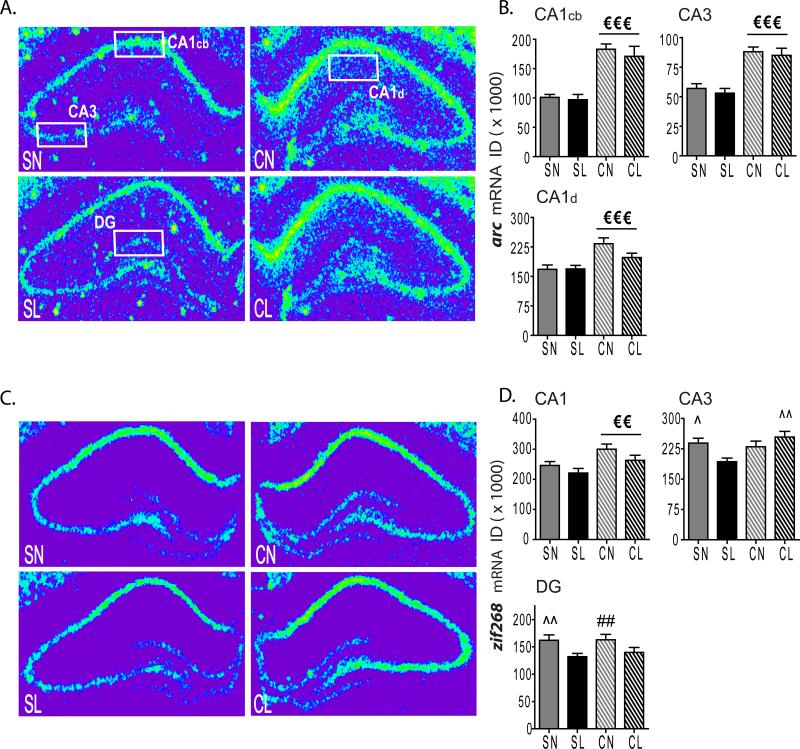

Gene expression in the dHPC following 22 h of abstinence

Twenty-two h after the end of self-administration, re-exposure to a cocaine-paired context significantly increased arc mRNA expression in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells and CA1 apical dendrites regardless of lever availability (Figure 4A-B). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug treatment for arc in CA1 cell bodies (F(1,26)=49.10, p<0.0001), CA1 apical dendrites (F(1,23)=13.91, p=0.001), and CA3 cell bodies (F(1,26)=41.11, p<0.0001), suggesting that recognition of a recently familiar cocaine-paired, but not saline-paired, context significantly increased CA1 activation. Arc expression was not measured within the dentate gyrus (DG) due to levels of expression below the limits of accurate detection.

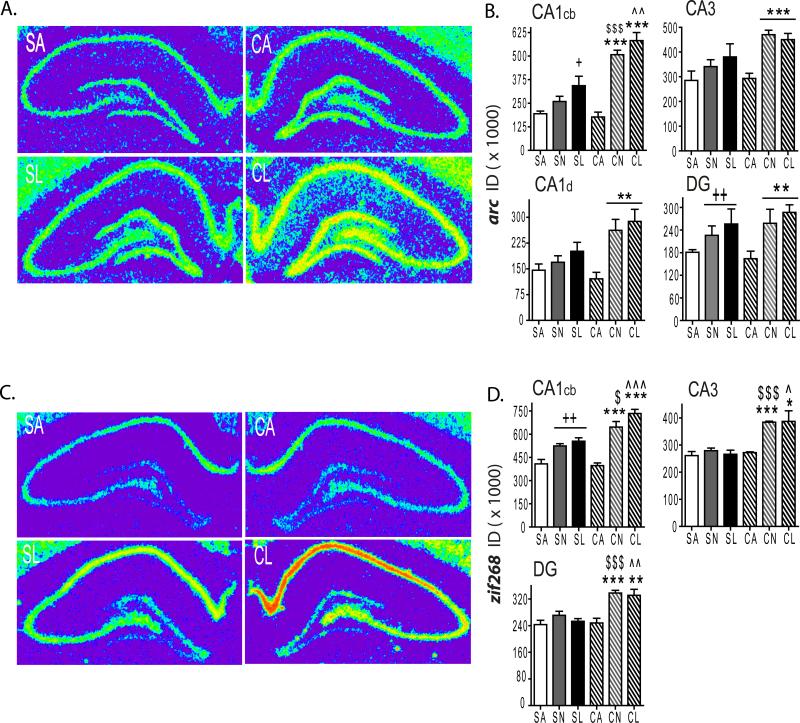

Figure 4.

After 22 h of abstinence, arc mRNA in CA1 and CA3, and zif268 in CA1, CA3 and DG subregions of the dHPC were increased during 1 h re-exposure to the cocaine-associated context. Representative coronal hemi-sections illustrating the expression pattern and quantitative analysis of the integrated density of the hybridization signal for arc (A,B) and zif268 (C,D) in the dorsal hippocampus. Regions of interest selected for measurement (white outlines) in CA1 pyramidal cells and apical dendrites, CA3, and DG are shown. ^p<.05, ^^p<0.01 vs. SL; ##p<.01 vs. CL; €€p<.01, €€€p<.001 cocaine (CN, CL) vs saline (SN, SL). Saline-no levers; SL, saline-levers available; CN, cocaine-no levers; CL, cocaine-levers available; CA1cb, CA1 cell body (pyramidal) layer; CA1d, CA1 dendritic (stratum radiatum) layer; ID, integrated density.

In contrast, following 22 h of abstinence, zif268 mRNA was differentially increased within subregions of the dHPC (Figure 4C-D). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug on zif268 mRNA in CA1 (F(1,24)=9.58, p=0.005) and a significant interaction of drug treatment by test environment (lever availability) in CA3 (F(1,24)=7.67, p=0.01). Multiple comparison tests revealed significantly higher levels of zif268 mRNA in CA3 of the CL group than in the SL group. Additionally, zif268 was significantly greater in the SN group than in the SL group, indicating a significant impact of lever availability during testing among cocaine and yoked-saline rats. In the DG, there was a significant main effect of environment (lever availability) on zif268 mRNA (F(1, 24)=8.66, p<0.01); both cocaine and saline-treated rats displayed significantly greater levels of zif268 after being returned to a context without levers than rats with lever access during the 1 h context test.

Gene expression in the dHPC following 15 d of abstinence

Following 15 days of abstinence, re-exposure to a cocaine-paired context increased arc mRNA levels in all sub-regions of the dHPC, independent of lever availability (Figure 5A-B). Interestingly, arc expression also increased in CA1 and DG of saline-treated rats re-exposed to the chamber in which they had received saline. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between drug treatment and test environment for arc mRNA in CA1 pyramidal cell bodies (F(2,20)=19.59, p<0.0001) and CA1 apical dendrites (F(2,20)=4.61, p<0.05). Multiple comparison tests revealed that arc mRNA was significantly greater in CA1 pyramidal cells of the CN and CL groups compared to the CA group, as well as SN and SL-treated rats, respectively. SL rats also displayed significantly greater levels of arc mRNA as compared to SA rats. CN and CL groups displayed significantly greater arc mRNA In CA1 apical dendrites than CA rats only. In CA3, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug treatment (F(1,20)=7.44, p<0.05) and test environment (F(2,20)=10.17, p<0.001). Multiple comparison tests revealed that arc mRNA was significantly greater in the CN and CL groups than in the CA group only. In contrast, in the DG, only a significant main effect of environment was found (F(2,17)=10.22, p<0.01), as cocaine and yoked-saline rats placed into the operant chamber displayed significantly greater mRNA levels compared to alternate environment-placed controls.

Figure 5.

After 15 d of abstinence, arc and zif268 mRNA in CA1, CA3, and DG of the dorsal hippocampus was increased during 1 h re-exposure to the cocaine-associated context. Representative coronal hemi-sections illustrating the expression pattern and quantitative analysis of the integrated density of the hybridization signal for arc (A,B) and zif268 (C,D) in the dorsal hippocampus. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. CA; $p<0.05, $$$p<0.001 vs. SN; ^p<0.05, ^^p<0.01, ^^^p<0.001 vs. SL; +p<0.05, ++p<0.01 vs. SA. SA, saline-alternate environment; CA, cocaine-alternate environment; SN, saline-no levers; SL, saline-levers available; CN, cocaine-no levers; CL, cocaine-levers available; CA1cb, CA1 cell body (pyramidal) layer; CA1d, CA1 dendritic (stratum radiatum); ID, integrated density.

Two-way ANOVA of zif268 mRNA within CA1 revealed a significant interaction of drug-treatment and test environment (F(2,19)=7.71, p<0.01). Multiple comparison tests showed that zif268 mRNA was significantly greater in CN and CL rats compared to CA, as well as SN and SL groups, respectively. Additionally, zif268 mRNA in CA1 pyramidal cells was greater in SN and SL groups than in SA rats . A significant interaction of drug treatment and test environment was found for zif268 mRNA in CA3 (F(2,19)=12.75, p<0.001) and DG (F(2,19)=3.94, p<0.05) whereas zif268 mRNA was significantly greater in CN and CL groups than in CA groups, and their respective yoked-saline controls in both regions (Figure 5C-D).

Behavioral correlations with gene expression

In order to determine if the intensity of gene expression positively correlated with active lever pressing as a measure of drug-seeking, a simple regression analysis was used to obtain correlation coefficients for gene expression and total lever presses during the 1 h test session. No significant correlation was found between the number of active lever presses and any of the genes in the dHPC or BLA of 22 h abstinence animals (data not shown). However, following 15 days of abstinence, lever pressing was significantly correlated with an increase in zif268 mRNA, only in the BLA (R^2 =0.916, p=0.01). No significant correlations were found for any genes within the dHPC following 15 days of abstinence.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated induction of the effector IEG, arc, and the transcription factor IEG, zif268, within the BLA and dHPC of rats immediately following a 1 h re-exposure to a previously drug-paired context following short and long periods of abstinence. Twenty two h following the end of chronic cocaine self-administration, arc mRNA was selectively increased in the BLA of cocaine-treated rats re-exposed to the operant chamber with levers extended compared to cocaine-treated rats without lever access and yoked-saline rats with levers available, whereas zif268 mRNA was only increased in the cocaine-treated rats with available levers relative to yoked-saline rats with available levers. In contrast, following 15 d of abstinence, re-exposure to a cocaine-paired context significantly increased arc mRNA in the BLA independent of lever availability whereas zif268 mRNA was selectively increased in cocaine-treated groups re-exposed to the operant chamber with levers extended compared to both cocaine-treated groups without levers and the yoked-saline group with levers extended. In the dHPC following 22 h of abstinence, arc mRNA was increased in CA1 (pyramidal cell bodies and apical dendrites) and CA3 subregions of rats with a cocaine history, independent of lever availability. Zif268 mRNA was increased in CA1 of cocaine-exposed rats independent of lever availability; however, there was a significant impact of lever availability in the DG and a significant interaction of drug and lever availability in CA3. Following 15 days of abstinence, re-exposure to a previously cocaine-, but not yoked-saline-paired context significantly increased arc mRNA within CA1 apical dendrites and CA3 cell bodies compared to rats placed into a recently familiar alternate environment. In contrast, within CA1 cell bodies and DG, re-exposure to a cocaine and yoked-saline paired context significantly increased arc mRNA compared to alternate environment controls; however only in CA1 were these increases further potentiated in animals returned to a context previously associated with cocaine self-administration. Similarly, zif268 was increased in CA1 by re-exposure to a remotely familiar context regardless of its salience relative to alternate environment controls, and was further potentiated if that context was previously associated with cocaine self-administration. In CA3 and DG, increases in zif268 were more selective to a cocaine-paired context, both of which were independent of lever availability. As discussed below, these combined results demonstrate that arc and zif268 mRNA expression share both similarities and differences in their temporal and spatial patterns when induced by re-exposure to a previously cocaine-paired context.

Functional significance of gene expression

Basolateral Amygdala

BLA lesions impair the ability of drug-associated cues to support cocaine-seeking (Whitelaw et al. 1996) and to reinstate extinguished cocaine-seeking in rats (Meil and See, 1997). Additionally, memories elicited by re-exposure to a previously learned drug-cue undergo BLA-dependent reconsolidation after each episode of retrieval or reactivation, allowing them to be updated accordingly (Nader et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2005). Relevant to this study, inhibition of arc and zif268 synthesis impairs distinct components of the learning and memory processes mediated by the BLA. In general, arc is believed to be involved in the consolidation of activity-dependent learning (Guzowski et al. 2000; Guzowski, 2002; Tzingounis and Nicoll, 2006; Messaoudi et al. 2007), and is highly correlated with new learning (Kelly and Deadwyler 2002, 2003) whereas zif268 is thought to be important for the reconsolidation of a retrieved memory (Hall et al. 2001; Thomas et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2004; Malkani et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2006). However, arc mRNA is also induced during the retrieval of both recent and remote spatial memory recall (Gusev et al. 2005). Following acute abstinence, the selective increase of arc mRNA in the BLA of cocaine-exposed rats with access to levers suggests that this induction may be associated with the context-induced drug-seeking behavior. Alternatively, because drug is no longer delivered upon active lever pressing, induction of arc may reflect extinction of previously conditioned instrumental responding. In contrast, following more prolonged abstinence, arc expression was increased in the BLA in both groups of cocaine-exposed rats regardless of lever availability. Thus, the latter increases likely do not reflect selective context-driven cocaine-seeking, but rather recognition of a previously cocaine-paired context.

Following both acute and prolonged abstinence, zif268 mRNA was increased in the BLA of cocaine-exposed rats with access to the levers relative to SL controls. However, following a 15 day absence from the self-administration chamber, zif268 mRNA induction responds more to the drug-paired lever than the chamber context, indicating activation specifically by a discrete cue that elicits cocaine-seeking. Moreover, zif268 mRNA within the BLA was significantly correlated with the number of active lever presses during drug context re-exposure only after 15 d of abstinence. This correlation reinforces the idea that the number of active lever presses selectively reflects increased incentive-salience of drug-associated cues after prolonged abstinence and that the intensity of zif268 expression in the BLA may encode this salience. In addition, induction of zif268 mRNA may function to retrieve drug cue memories or reconsolidate new information about the changed value of the environment and its contingencies. This interpretation is consistent with studies demonstrating a role of the BLA in modifying incentive value of cocaine-associated cues during extinction as suggested by Fuchs et al. (2002). Further, it is consistent with studies that have demonstrated amygdala-dependent reconsolidation of a well-learned conditioned-stimulus cocaine association that is disrupted by prior infusion of a zif268 antisense oligonucleotide (Lee et al. 2005, 2006).

Dorsal hippocampus

The dHPC plays a crucial role in the expression of drug context-induced cocaine-seeking (Fuchs et al. 2005, 2007) and the integrity of the dHPC is critical for the post-reactivation reconsolidation of memories that facilitate context-induced cocaine-seeking (Fuchs et al. 2009). Hippocampal subregions have been differentially implicated in processes of memory acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval. For example, CA3 and DG subregions are thought to work through the mossy fiber projections to encode spatial information during acquisition but may not be necessary for retrieval of this information (Lassalle, 2000; Lee and Kesner, 2004) whereas the CA1 and DG appear to be critically involved in retrieval of contextual memory (Kesner et al. 2004). Arc mRNA was significantly greater in CA1 (pyramidal cell bodies and apical dendrites) and CA3 of cocaine-experienced rats returned to the chamber at 22 h of abstinence. These increases do not likely reflect new learning associated with changes in environmental cues (levers) or extinguishing drug-seeking because lever availability during testing did not impact these increases; however it is possible that induction of arc in the dHPC may be important for modifying previously established context-drug associations, regardless of operant responding. Following prolonged abstinence, induction of arc mRNA was significantly greater in CA1 (cell bodies) and DG of rats returning to the operant chamber regardless of lever availability relative to alternate environment control conditions. However, arc expression was potentiated in CA1 pyramidal cells if the context was previously associated with cocaine vs. yoked-saline. These differences in zif268 expression in the DG and CA1 cell body layers suggest that re-exposure to a remotely familiar context increases arc mRNA in the DG regardless of previous drug treatment, whereas interactions between the environment and drug history induce arc expression in CA1 cell bodies when re-exposure to the drug-paired environment is temporally remote. These findings are consistent with the involvement of CA1 and DG in place recognition (Lee and Kesner, 2004; Kesner et al. 2004) and are of particular interest, based on previous findings that arc is repeatedly induced in the same network during exploration of the same space (Ramierez-Amaya et al. 2005). In contrast, the selective induction of arc in response to a cocaine-, but not yoked-saline paired context significantly increased arc mRNA in CA1 apical dendrites and CA3 cell bodies suggests that these increases reflect processes necessary for consolidating new information about the drug-paired context. This pattern of arc expression is consistent with CA1 recoding or consolidating information represented in the CA3 network to facilitate the transfer of information to the neocortex (Rolls, 1996; Kesner et al. 2004),

Twenty-two hours following the end of self-administration, cocaine-treated rats displayed significantly greater zif268 induction in CA1 and CA3 than in saline-treated rats returned to the operant chamber regardless of lever availability, suggesting that retrieval of a previously drug-paired contextual memory led to robust activation. Interestingly, induction of zif268 within the DG following 22 h of abstinence, was selective to rats without lever access independent of the context association, suggesting that increased activity within the DG occurred in response to the novelty of not having a lever during testing. Additionally, given the role of the DG in spatial pattern separation, (Kesner et al. 2004), the novelty of lever removal in a recently familiar context may promote activation of the DG that is not seen at a more remote time point. Following 15 d of abstinence, significantly greater zif268 mRNA expression in rats returned to an operant chamber relative to those placed in the more recently familiar alternate environment suggests that retrieval of a remotely familiar contextual memory significantly induces zif268 in CA1, and that the motivational salience of a cocaine-paired context may further potentiate activation of this dHPC subregion. This interpretation is consistent with previous work demonstrating a critical role for zif268 in the retrieval of contextual memories (Hall 2001; Thomas et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2004; Malkani et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2006). Contrary to CA1, increases in CA3 and DG were selective to the cocaine-paired context, suggesting that induction of zif268 may reflect cellular processes necessary for reconsolidating information regarding the changed value of the environment.

The relationship between the function of the context and the recruitment of the dHPC in processes of learning and memory is a highly complex relationship. Spatial (hippocampus-dependent) and cued (hippocampus-independent) learning in a water maze cause equivalent increases in hippocampal expression of arc and zif268 (Guzowski et al. 2001), suggesting that increased activity within the dHPC may not necessarily reflect a specific behavior. Consistent with this idea, in the current study, no correlations were found between active lever responding during the 1 h context re-exposure and activity-regulated gene expression in the dHPC. Furthermore, it is possible that increased activity-regulated gene expression within the hippocampal network may reflect sequential information processing within the larger contextual and cue-induced drug-seeking circuitry (Fuchs et al. 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

Mapping the selective regional patterns and identifying the function of activity-regulated genes under specific environmental conditions can provide a clearer understanding of the neurobiological substrates of cocaine addiction and the molecular mechanisms underlying drug seeking and drug use. The induction of arc and zif268 in rats re-exposed to a previously cocaine-paired context suggests that regions of the hippocampus and amygdala participate in the associative processing of complex drug-associated, contextual stimuli. Although these genes share a critical dependence on intracellular signaling pathways that connect nuclear and synaptic events, differences in their expression patterns indicate that they regulate variant molecular processes in the response to the motivational effects of a cocaine-paired context.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Shannon Ghee and Anthony Carnell for excellent technical support. This research was supported by P50 DA015369 and T32 DA07288.

Abbreviations

- arc

Activity-regulated cytoskeleton gene

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CA

cocaine alternate environment

- CN

cocaine no lever

- CL

cocaine lever available

- DG

dentate gyrus

- dHPC

dorsal hippocampus

- ID

integrated density

- SA

saline alternate environment

- SN

saline no lever available

- SL

saline lever available

- SEM

standard error mean

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Berke JD, Hyman SE. Addiction, dopamine, and the molecular mechanisms of memory. Neuron. 2000;25:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Amer J Psychiat. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:169–73. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Childress AR, O'Brien CP. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology. 1992;107:523–552. doi: 10.1007/BF02245266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Second-order schedules of drug reinforcement in rats and monkeys: measurement of reinforcing efficacy and drug-seeking behaviour. Psychopharmacology. 2000;153:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130000566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Eaddy JL, Su Z, Bell GH. Interactions of the basolateral amydala with the dorsal hippocampus and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex regulate drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Ledford CC, Parker MP, Case JM, Mehta RH, See RE. The role of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and dorsal hippocampus in contextual reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;30:296–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Branham RK, See RE. Differential neural substrates mediate cocaine seeking after abstinence versus extinction training: a critical role for the dorsolateral caudate-putamen. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3584–3588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5146-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Bell GH, Ramirez DR, Eaddy JL, Su ZI. Basolateral amygdala involvement in memory reconsolidation processes that facilitate drug context-induced cocaine seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:889–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Weber SM, Rice HJ, Neisewander JL. Effects of excitotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala on cocaine-seeking behavior and cocaine conditioned place preference in rats. Brain Res. 2002;929:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, Phillips RL, Kimes AS, Margolin A. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12040–12045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, See RE. Dissociation of primary and secondary reward-relevant limbic nuclei in an animal model of relapse. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;22:473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev PA, Cui C, Alkon DL, Gubin AN. Topography of Arc/Arg3.1 mRNA expression in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus induced by recent and remote spatial memory recall: dissociation of CA3 and CA1 activation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9384–9397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0832-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Inhibition of activity-dependent arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Setlow B, Wagner EK, McGaugh JL. Experience-dependent gene expression in the rat hippocampus after spatial learning: a comparison of the immediate-early genes Arc, c-fos, and zif268. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5089–5098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF. Insights into immediate-early gene function in hippocampal memory consolidation using antisense oligonucleotide and fluorescent imaging approaches. Hippocampus. 2002;12:86–104. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Thomas KL, Everitt BJ. Cellular imaging of zif268 expression in the hippocampus and amygdala during contextual and cued fear memory retrieval: selective activation of hippocampal CA1 neurons during the recall of contextual memories. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2186–2193. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02186.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing MC, Miller SW, See RE, McGinty JF. Relapse to cocaine-seeking increases activity-regulated gene expression differentially in the prefrontal cortex of abstinent rats. Psychopharmacol. 2008a;198:77–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing MC, See RE, McGinty JF. Relapse to cocaine-seeking increases activity-regulated gene expression differentially in the striatum and cerebral cortex of rats following short or long periods of abstinence. Brain Struct Funct. 2008b;213:215–27. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Schweitzer JB, Quinn CK, Gross RE, Faber TL, Muhammad Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:334–341. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich PJ, See RE. Differential contributions of the basolateral and central amygdala in the acquisition and expression of conditioned relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC155–158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle JM, Rataille T, Halley H. Reversible inactivation of the hippocampal mossy fiber synapses in mice impairs spatial learning, but neither consolidation nor memory retrieval, in the Morris navigation task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;73:243–257. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential contributions of dorsal hippocampal subregions to memory acquisition and retrieval in contextual fear-conditioning. Hippocampus. 2004;14:301–310. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MP, Deadwyler SA. Acquisition of a novel behavior induces higher levels of Arc mRNA than does overtrained performance. Neurosci. 2002;110:617–626. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MP, Deadwyler S. Experience-dependent regulation of the immediate early gene arc differs across brain regions. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6443–6451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06443.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Lee I, Gilbert P. A behavioral assessment of hippocampal function based on a subregional analsis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;15:333–351. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Di Ciano P, Thomas KL, Everitt BJ. Disrupting reconsolidation of drug memories reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuron. 2005;47:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Everitt BJ, Thomas KL. Independent cellular processes for hippocampal memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Science. 2004;304:839–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1095760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Milton AL, Everitt BJ. Cue-induced cocaine seeking and relapse are reduced by disruption of drug memory reconsolidation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5881–5887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkani Al, Wallace KJ, Donley MP, Rosen JB. An egr-1 (zif268) antisense oligonucleotide infused into the amygdala disrupts fear conditioning. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:617–624. doi: 10.1101/lm.73104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SJ, Grimwood PD, Morris RGM. Synaptic Plasticity and Memory: An evaluation of the hypothesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:649–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CK, Miyashita T, Setlow B, Marjon KD, Steward O, Guzowski JF, McGaugh JL. Memory-influencing intra-basolateral amygdala infusions modulate expression of Arc protein in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10718–10723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504436102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, See RE. Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2003;168:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meil WM, See RE. Conditioned cued responding following prolonged withdrawal from self-administered cocaine in rats: an animal model of relapse. Behav Pharmacol. 1996;7:754–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meil WM, See RE. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala abolish the ability of drug-associated cues to reinstate responding during withdrawal from self-administered cocaine. Behav Brain Res. 1997;87:139–48. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi E, Kanhema T, Soule J, Tiron A, Dagyte G, da Silva B, Bramham CR. Sustained Arc/Arg3.1 synthesis controls long-term potentiation consolidation through regulation of local actin polymerization in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10445–10455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2883-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406:722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug-addiction: a model for the molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramierez-Amaya V, Vazdarjanova A, Mikhael D, Rosi S, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Spatial exploration-induced Arc mRNA and protein expression: evidence for selective, network-specific reactivation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1761–1768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4342-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez DR, Bell GH, Lasseter HC, Xie X, Traina SA, Fuchs RA. Dorsal hippocampal regulation of memory reconsolidation processes that facilitate drug context-induced cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;5:901–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. A theory of hippocampal function in memory. Hippocampus. 1996;6:601–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<601::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KL, Arroyo M, Everitt BJ. Induction of the learning and plasticity-associated gene Zif268 following exposure to a discrete cocaine-associated stimulus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1964–1972. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzingounis AV, Nicoll RA. Arc/Arg3.1: linking gene expression to synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2006;52:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Dose-dependent alteration in zif/268 and preprodynorphin mRNA expression induced by amphetamine or methamphetamine in rat forebrain. J Pharmacol Exper Therap. 1995;273:909–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw RB, Markou A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Excitotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala impair the acquisition of cocaine-seeking behavior under a second-order schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacol. 1996;127:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala AR, Osredkar T, Joyce JN, Neisewander JL. Upregulation of Arc mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex following cue-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Synapse. 2008;62:421–431. doi: 10.1002/syn.20502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]