Abstract

The capacity to remember sequences is critical to many behaviors, such as navigation and communication. Adult humans readily recall the serial order of auditory items, and this ability is commonly understood to support, in part, the speech processing for language comprehension. Theories of short-term serial recall posit either use of absolute (hierarchically structured) or relative (associatively structured) position information. To date, neither of these classes of theories has been tested in a comparative auditory model. European starlings, a species of songbird, use temporally structured acoustic signals to communicate, and thus have the potential to serve as a model system for auditory working memory. Here, we explore the strategies that starlings use to detect the serial order of ecologically valid acoustic communication signals and the limits on their capacities to do so. Using a two-alternative choice operant procedure, we demonstrate that starlings can attend to the serial ordering of at least four song elements (motifs) and can use this information to classify differently ordered sequences of motifs. Removing absolute position cues from sequences while leaving relative position cues intact, causes recognition to fail. We then show that starlings can, however, recognize motif sequences using only relative position cues, but only under rigid circumstances. The data are consistent with a strong learning bias against relative position information, and suggest that recognition of structured vocal signals in this species is inherently hierarchical.

Keywords: working memory, serial recall, communication, songbirds, European starling

The capacity to remember the sequential order of sensory stimuli over short-term intervals is requisite for many natural behaviors, including human language processing. Most models of memory (e.g. Repovs & Baddeley, 2006; Jonides et al., 2008) posit information-specific buffers to account for memory differences across sensory modalities. Consistent with this, the auditory system appears to be specialized for higher working memory capacity, relative to capacities in other modalities (Jonides et al., 2008) – probably through its extensive experience with phonological processing (Boutla, Supalla, Newport, & Bavelier, 2004). Multiple-store models typically describe the working memory for auditory signals with a specialized sub-system, termed the phonological loop (Repovs & Baddeley, 2006; c.f. Wright & Rivera, 1997), that is thought to facilitate language acquisition by storing and recalling sequential novel phonemes via rehearsal (Baddeley, Gathercole, & Papagno, 1998). To date, the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie working memory for auditory sequences remain poorly understood, in part, because no suitably complex animal model has emerged. Here, we describe a series of initial studies on the working memory for auditory sequences in European starlings, a species of songbird with demonstrated similarities to humans in working memory performance (Zokoll et al., 2008).

Human serial-order models

Two general theoretical frameworks have been used to model storage and retrieval of serial-order information in human working memory. Chaining models (Henson, 2001) derive from classic stimulus-response theories of serial behavior, and suggest that individual items are coded in association with their preceding and/or succeeding elements. Ordinal position models (e.g. Conrad, 1965), on the other hand, contend that each individual item is coded by its specific position within a sequence (i.e., not to other items in the sequence) or its position relative to the start and/or end of the sequence (e.g. start-end model; Henson, 1998). Further, the latter model of edge-based positional learning has recently garnered considerable support from studies of artificial-language acquisition in human adults (for review see Endress et al, 2009). Whereas chaining can be explained by general process theories of associative learning, ordinal position coding requires comprehension of hierarchical organization (e.g. Fountain, Henne, & Hulse, 1984; Terrace, 1987). Indeed, the general notions of chaining and ordinal position have a long and important history in understanding the organization of serial behavior (Lashley, 1951), and in the birth of modern “cognitive” theories of psychology. Given that hierarchical structure and processing are hallmarks of human language (Hauser, Chomsky, & Fitch, 2002), it is important to understand how serially organized signals (particularly communication signals) are processed. Most data from humans suggest that ordinal position models do a better job than chaining models of accounting for various patterns of human performance (Henson, 1998).

The notions of chaining and ordinal position also have a long history in studies of serial learning in non-human animals (e.g. Straub, Seidenberg, Bever, & Terrace, 1979). Despite important differences between species (D'Amato & Colombo, 1988; Straub & Terrace, 1981), all those investigated rely on various degrees of ordinal position information to learn and recall serially ordered lists of visual items. Thus, positional coding theories are thought to provide good, though incomplete, accounts for serial pattern learning in many animals (Fountain, 2006; Terrace, 2006). One shortcoming of the previous animal studies, however, is that they have been conducted almost exclusively using simple and/or arbitrary visual stimuli. Therefore we know very little about the generality of serial processing across sensory modalities, and nothing about these processes in the context of ecologically relevant signals. This lack of research is surprising given the prominent and specialized role of serial patterning and working memory in speech processing.

Starling song recognition

The present study investigates the role of absolute (positional) and relative (chaining) information in the working memory for sequentially ordered units of natural acoustic communication signals in European starlings. Starlings have elaborate, temporally structured vocal communication signals, remarkable pattern recognition capabilities, and an auditory system well studied at the neurobiological level. Starling song is hierarchically structured. Males tend to sing in long continuous bouts (Adret-Hausberger & Jenkins, 1988; Eens, Pinxten, & Verheyen, 1991) that, in turn, are composed of still shorter units called notes, a possible analog to the phonemes comprising human speech (Doupe & Kuhl, 1999). Notes can be broadly classified by the presence of continuous energy in their spectro-temporal representations (Gentner, 2008). Although a motif may consist of several notes (Gentner, 2008), the note pattern within a motif is usually stereotyped between successive renditions of that motif. Commonly, each motif is repeated two or more times before the next one is sung. Thus, starling song appears (acoustically) as a sequence of changing motifs, where each motif is an acoustically complex event.

As in other songbird species, starlings are expert at recognizing conspecific individuals by the songs they sing (Gentner & Margoliash, 2002; Stoddard, 1996). To do so, starlings rely on the motifs produced by different singers (Gentner & Hulse, 1998, 2000). They attend to the sequencing of motifs in song bouts (Gentner & Hulse, 1998) and to the temporal patterning of sub-motif features (Gentner, 2008). Motifs and motif -patterns have direct correlates in the action potential discharge rates of individual neurons in regions of the starling forebrain analogous to mammalian secondary auditory cortices (Gentner & Margoliash, 2003; Thompson & Gentner, 2007). The behavioral and neural sensitivity to temporal patterning at the supra- and sub-motif levels implies a dynamic working memory that subserves the longer-term learning processes for song recognition. Indeed, starlings can learn to recognize a variety of complex patterns instantiated over sets of their natural song motifs (Gentner, Fenn, Margoliash, & Nusbaum, 2006). Understanding auditory working memory in the context of starlings’ natural communication signals will provide an important comparative perspective for similar processes in humans, particularly if the method by which starlings recall sequences of auditory objects broadly parallels the ordinal position models that best represent serial-order reporting in humans.

Using an operant conditioning procedure, we trained European starlings to report the serial order of a sequence of vocal communication units (motifs) presented on each trial. In experiment one, we investigated working memory for motif-sequences when both relative and absolute position cues are available. In experiment two, we removed absolute motif position as a potential cue for recall of motif serial order on a single trial. Overall, the results demonstrate that working memory in starlings is strongly biased by absolute position information about the serial order of natural vocalizations. Under appropriate circumstances, however, relative position information can also be retained and used.

EXPERIMENT ONE

In the first experiment, we test whether starlings can learn to accurately report serial order for a given motif-sequence using relative and/or absolute position cues. Relative position cues consist of information available in the transitions between ordered pairs, triplets or longer runs of motifs. Absolute position cues consist of information available in the occurrence of a given motif at a specific position in the sequence, implying knowledge about the item and the location. Consider a four-motif sequence denoted as A-B-C-D. Relative cues allow starlings to learn that motif D follows motif C, which follows B, which follows A. Absolute cues allow starlings to learn that motif D occurs in the last position, C in the second-to-last, etc. These two kinds of information are not mutually exclusive and may both, in theory, contribute to motif-sequence recognition. After demonstrating that starlings can learn to recognize strings of the same motifs ordered in different sequences, we used four test conditions to understand (1) the strategies starlings employ to recognize serial-ordered motif-sequences and (2) the temporal limits of working memory in this recognition behavior.

METHODS

Subjects

Six wild-caught European starlings served as subjects. All subjects were caught in southern California in May 2006. All had full adult plumage at the time of capture, and thus were at least one year old. From the time of capture until their use in this study, all subjects were housed in large mixed sex, conspecific aviaries with ad libitum access to food and water. The photoperiod in the aviary and the testing chambers followed the seasonal variation in local sunrise and sunset times. No significant sex differences have been observed in previous studies of individual vocal recognition (Gentner & Hulse, 2000) and the sex of subjects in this study was not controlled. Following test condition one, two starlings were resigned from the experiment for a failure to return to baseline discrimination, leaving four subjects to be used in test conditions two through four.

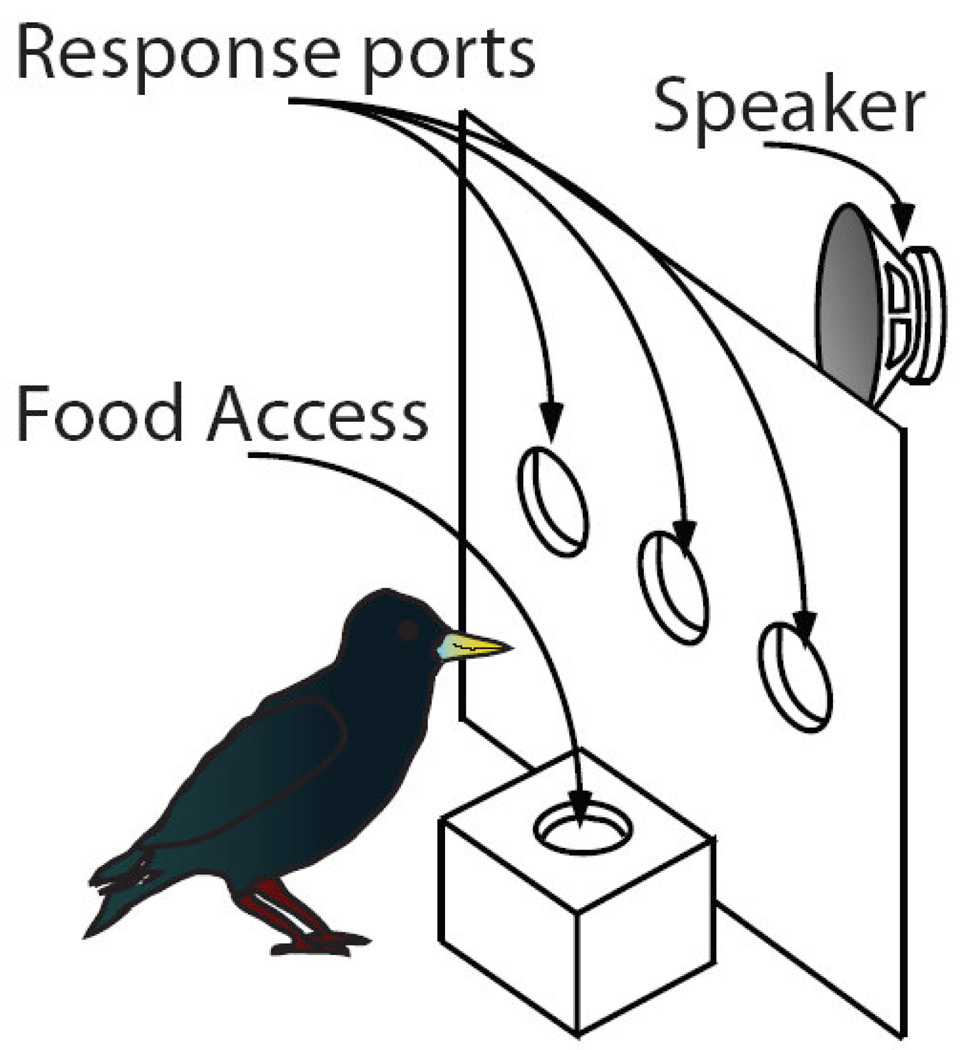

Apparatus

Starlings learned to classify the training stimuli using a custom-built operant apparatus (Fig. 1), housed in a 61 × 81 × 56 cm ID sound attenuation chamber (Acoustic Systems). Inside the chamber, a subject was held in a weld-wire cage (41 × 41 × 35 cm) that permitted access to a 30 × 30 cm operant panel mounted on one wall. The operant panel contained three circular response ports spaced 6 cm center-to-center, aligned in a row with the center of each port roughly 14 cm off the floor of the cage and with the whole row centered on the width of the panel. Each response port was a PVC housed opening in the panel fitted with an IR receiver and transmitter that detected when the bird broke the plane of the response port with its beak. This ‘poke-hole’ design allows starlings to probe the apparatus with their beaks, in a manner akin to their natural appetitive foraging behavior. Independently controlled light-emitting diodes (LEDs) could illuminate each response port from the rear. A fourth PVC-lined opening provided access to food directly below the center port, in the section of cage floor immediately adjacent to the panel. A remotely controlled hopper, positioned behind the panel, moved the food into and out of the subject’s reach beneath the opening. Acoustic stimuli were delivered through a small full-range audio speaker mounted roughly 30 cm behind the panel and out of the subject’s view. The sound pressure level inside all chambers was calibrated to the same standard broadband noise signal. Custom software monitored the subject’s responses, and controlled the LEDs, food hoppers, chamber light and auditory stimulus presentation according to procedural contingencies. Full details for all the mechanical components of the apparatus, audio interface, digital I/O control hardware, and custom software are available upon request.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of operant apparatus. Subjects start a two-alternative choice trial and presentation of a motif-sequence by pecking the center response port. After the stimulus completes, the subject pecks at either the left or right response ports depending on the class from which the stimulus was drawn (low-entropy motif-sequence or high-entropy motif-sequence). Correct responses yield food reward. Incorrect responses lead to a short “time out” during which the house light is extinguished and food is inaccessible.

Procedures

Subjects were trained to use the apparatus using standard operant conditioning procedures.

Shaping

Subjects learned to work the apparatus through a series of successive shaping procedures. Upon initially entering the operant chamber, the subject was given unrestricted access to the food hopper, and then taught through auto-shaping to peck at the blinking LED in the center port to gain access to the food. Once the subject pecked reliably at the center port to obtain food, the center LED ceased flashing, while the requirement to peck at the same location remained in effect. Shortly thereafter, pecks to the center port initiated the presentation of a song stimulus, and the trial proceeded as described below. In all cases, initial shaping occurred within one to two days, and was followed immediately by the start of baseline sequence recognition training.

Baseline sequence recognition training

Each subject learned initially to classify generated motif-sequences that followed a static (‘low entropy’) sequence, or a random (‘high entropy’) sequence. Subjects initiated a trial by pecking at the center response port to trigger the immediate presentation of a high- or low-entropy motif-sequence, selected at random (p=0.5). The explicit motif-sequence for a given trial was synthesized just prior to presentation during the inter-trial-interval, according to pre-determined probabilities (see the section labeled “Stimuli”). Following completion of the motif-sequence, the subject was required to peck either the left or the right response port within 2 s. For half of the subjects, low entropy motif-sequences were associated with the left response port and high-entropy sequences with the right port. For the other half of the subjects, these response contingencies were reversed. A peck to the correct response port during the response window allowed access to the food hopper for 2.5 s. Pecks to the incorrect response port were punished by extinguishing the house light for 2 – 10 s without access to food. Responses prior to completion of the stimulus were ignored. The trial ended when either the food hopper retracted following a correct response, or the house light re-illuminated following an incorrect response. The inter-trial interval was 2 s. Incorrect responses, and any trial in which the subject failed to peck either the left or the right key within 2 s of stimulus completion, initiated a correction-trial sequence during which the initiating stimulus was repeated on all subsequent trials until the animal eventually responded correctly. None of the correction trial data, including the subject’s eventual correct response, are included in the analyses.

Subjects were on a closed economy during training, with daily sessions lasting from sunrise to sunset. Each subject could run as few or as many trials per day as they were able. Food intake was monitored daily to ensure each subject’s wellbeing. Water was always available. All procedures were approved by the UCSD institutional animal care and use committee whose policies are consistent with the Ethical Principles of Cognition.

Testing procedures

Following stable recognition of the baseline training sequences (at least 75% correct or better for two consecutive days), the rate of food reinforcement for correct responses was lowered from 100% to 60% and the rate of “punishment” for incorrect responses was lowered from 100% to 60%. Subjects’ performance was again allowed to reach stable asymptote (typically within one or two days), at which point we began the first of several test conditions.

During test conditions, the baseline training stimuli were presented on 80% of the trials and test stimuli were presented on 20% of the trials. Correct (and incorrect) responses to the baseline training stimuli were reinforced (or punished) 60% of the time. Any response to the left or right port on a test stimulus trial was randomly reinforced 30% of the time or punished 30% of time without regard to the location of the subject’s response. The remaining 40% of responses on the test-stimulus trials yielded no operant outcome. Because reinforcement contingencies for the test stimuli were random and non-differential with respect to response, subjects had no opportunity to learn to associate a given test stimulus with a given response. Thus, the subjects’ differential responses to the randomly occurring test stimuli are based only on learning tied to the baseline training stimuli. This reinforcement regimen permits, in the context of lowered reinforcement for the baseline stimuli, the presentation of large numbers of test stimuli over multiple sessions. All comparisons were made among contemporaneously presented test and baseline stimuli to account for any drift or systematic change in performance. Correction trials were not used during test sessions thereby further dampening the possibility that subjects would learn any new response associations for a test stimulus. Each test condition spanned several sessions (days). To meet statistical power requirements we collected a minimum of 20 trials per relevant condition, but typically many more (see results). Between testing conditions, the subject returned to the baseline recognition training with reduced (60%) reinforcement contingencies.

Stimuli

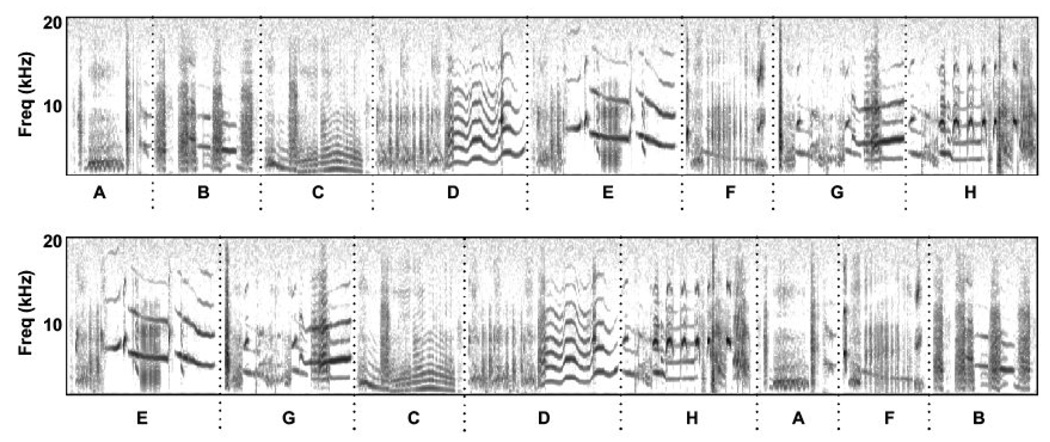

We extracted eight unique (non-repetitious) warble motifs from the songs of one male starling to create the experimental stimuli. Details on song recording have been described elsewhere (Gentner & Hulse, 1998). With the eight extracted motifs, we designed two types of motif-sequences (high- and low- entropy; Fig. 2) that subjects learned to recognize during baseline training in experiment one. From the same eight motifs we also created motif-sequences for four different test conditions (Table 1). Each test condition allowed us to test hypotheses about specific strategies subjects could have used to recognize the high- and low-entropy motif-sequences, and to explore working memory for patterned strings of acoustic communication signals in this species.

Fig. 2.

Example baseline training stimuli. Spectrograms showing power in the frequency domain as a function of time for (top) an example low-entropy sequence of starling motifs, and (bottom) the same eight motifs rearranged to show an example high-entropy sequence (see text, Table 1). The vertical dotted black lines denote motifs in both sequences. Letters below the spectrogram give the labels for specific motifs. Total duration of both spectrograms is 8.5 sec.

Table 1.

Motif-sequence designs for training and test stimuli in experiment one. Table shows the likelihood that a given motif will occur at a given position in a sequence in a given experimental condition. For example, in the “Baseline Low-entropy” condition, motif C occurs in the third position 93% of the time. Sequence notations used in the text are shown for sequences in test conditions three and four.

| Condition | Position assignments | Notation in text | Occurrence likelihood (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline High-entropy |

[ABCDEFGH] | - | 12.5 |

|

Baseline Low-entropy |

[ABCDEFGH] | - | 93 |

|

Test Condition One |

[ABCDEFGH] | - | 23 |

| [ABCDEFGH] | 33 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 44 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 54 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 65 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 75 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 75 | ||

| [ABCDEFGH] | 85 | ||

|

Test Condition Two |

[Axxxxxxx] | - | 99 |

| [xBxxxxxx] | 99 | ||

| [xxCxxxxx] | 99 | ||

| [xxxDxxxx] | 99 | ||

| [xxxxExxx] | 99 | ||

| [xxxxxFxx] | 99 | ||

| [xxxxxxGx] | 99 | ||

| [xxxxxxxH] | 99 | ||

|

Test Condition Three: Adjacent |

[ABCxxxxx] | /ABC/ | 99 |

| [xBCDxxxx] | /BCD/ | 99 | |

| [xxCDExxx] | /CDE/ | 99 | |

| [xxxDEFxx] | /DEF/ | 99 | |

| [xxxxEFGx] | /EFG/ | 99 | |

| [xxxxxFGH] | /FGH/ | 99 | |

|

Test Condition Three: Non-adjacent |

[AxCxExxx] | /ACE/ | 99 |

| [xBxDxFxx] | /BDF/ | 99 | |

| [xxCxExGx] | /CEG/ | 99 | |

| [xxxDxFxH] | /DFH/ | 99 | |

|

Test Condition Four |

[ABCDEFxx] | /-xx/ | 99 |

| [ABCDEFGx] | /-Gx/ | 99 | |

| [ABCDEFxH] | /-xH/ | 99 | |

| [ABCDEFGH] | /-GH/ | 99 |

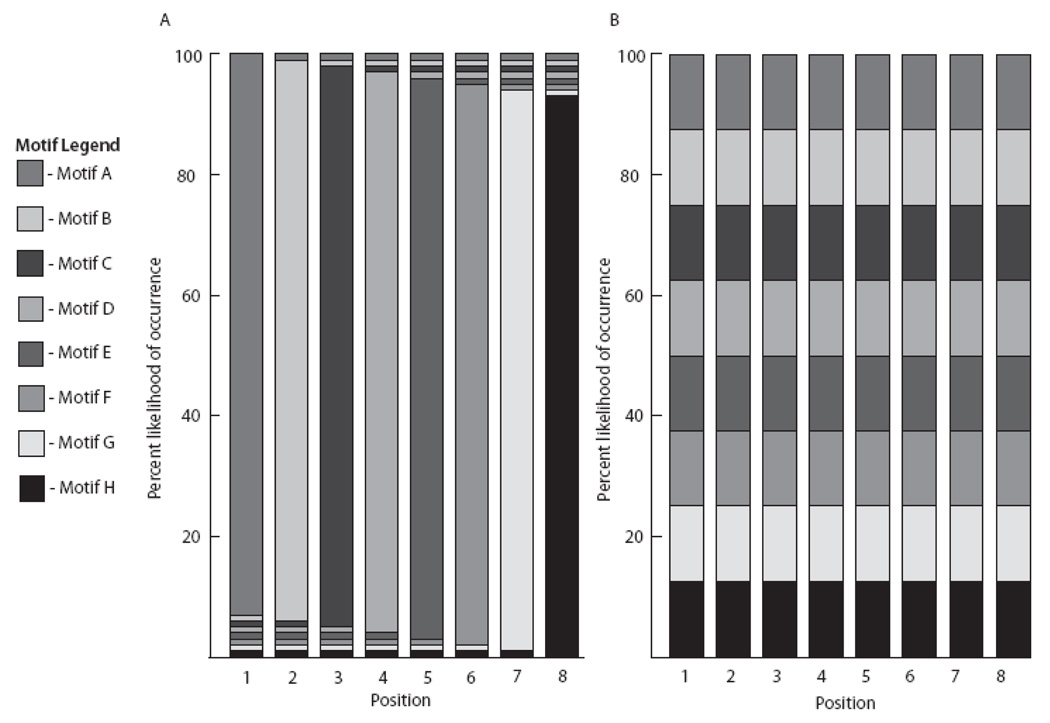

Baseline training

We generated the baseline training stimuli by arranging the eight motifs into two types of sequences, one in which the serial ordering of motifs was largely static, and a second in which the serial ordering was maximally random (Fig. 3). We term these two classes of motif-sequences “low-entropy” and “high-entropy” sequences, respectively. We assigned each of the eight motifs (A-H) to a single position (1–8). In the low-entropy sequences, a given motif occurred at its assigned position 93% of the time, and each of the remaining seven motifs occurred at that position 1% of the time (Fig. 3; Table 1). For example, motif H occurred at position 8 in 93% of the low-entropy sequences, and motifs A through G each occurred in position 8 in 1% of the low-entropy sequences. As such, roughly 56% of the low-entropy stimuli followed the sequence form [ABCDEFGH] exactly. The high-entropy sequences were constructed in the same way as the low-entropy sequences, except that each motif (A-H) occurred at its assigned position (1–8, respectively) only 12.5% of the time; thus all eight motifs were equally likely to occur at any location (Fig. 3; Table 1). For all sequences, the selection of a motif at a given location was independent of the motif selected at all other locations. This meant that repetitions could occur at adjacent and non-adjacent sequence positions.

Fig. 3.

Schematic showing the probabilistic organization for the motif-sequences in the (A) low- and (B) high-entropy baseline training stimuli. Each panel shows the likelihood (along the y-axis) that a given motif (denoted by different grayscale bars) will occur in a given position (x-axis). For low-entropy sequences (A), one particular motif had a high (93%) chance of occurring at one position, and all other motifs had a low (1%) chance of occurring in that same position. As such, low-entropy sequences were heard as [ABCDEFGH] 56% of the time. High-entropy sequences (B) afforded equal opportunity for any motif to occur in any position, thereby generating a more random sequence of motifs.

Test Condition One: varying motif-sequence reliability

We constructed seven stimulus classes for test condition one. In each class, we held constant the likelihood that all motifs (A-H) occurred in their assigned positions (1–8, respectively). The seven classes spanned the range of possible likelihoods between the baseline high- and low-entropy sequences in roughly evenly spaced steps from 23% to 85% (Table 1, Fig. 3). When, in a given sequence, the motif assigned to a particular position was not selected, we chose one of the seven remaining motifs with equal probability. The stimuli in condition one were designed to test starlings’ sensitivity to changes in the reliability of motif ordering within in a sequence. Test conditions two through four examine the nature of this sensitivity.

Note that in test conditions one through four, the likelihood that any particular motif occurred at any position never exceeded 99%. Thus, all the test stimuli retained at least a small degree of sequence variability that mirrors the natural dynamics of sequence variability in this species.

Test Condition Two: varying single-motif reliability

We constructed eight stimulus classes for test condition two (Table 1). Within each class, we set the likelihood of a single motif occurring at its assigned position to 99%, and the likelihood that any of the seven remaining motifs occurred at any of the seven remaining positions equal (14.29%). For example, we tested subjects with sequences of the form [xxxxxxxH], where x denotes the occurrence of any motif A–H with equal probability, and H denotes the occurrence of motif H in 99% of the sequences in this class. Thus, if a subject relied on the regular occurrence of a single motif at a given position (e.g. motif H at position eight), then only those sequences in which the motif occurred reliably at the same position assignment as in training will control behavior.

Test Condition Three: varying multiple-motif reliability

We created ten stimulus classes for test condition three (Table 1). In classes one through six we set the likelihood of occurrence for consecutive-motif triplets /ABC/, /BCD/, /CDE/, /DEF/, /EFG/, and /FGH/, respectively, to 99%. For example, one class of sequences took the form [xxxDEFxx], where x denotes the occurrence of any motif A, B, C, G, and H with equal probability (20%), and DEF denotes the occurrence of motifs D, E, and F in their assigned positions in 99% of the sequences. Classes seven through ten had forms similar to classes one through six, except that the following non-adjacent motif-triplets were biased to occur in their assigned positions 99% of the time: /ACE/, /BDF/, /CEG/, and /DFH/. These test stimuli allowed us to assess the subjects’ reliance on second- and third-order motif configurations to recognize the serially ordered baseline motif-sequences.

Test Condition Four: testing position biases

In test condition four, we focused on the importance of the motifs heard in the penultimate and ultimate positions in the sequence. We created four stimulus classes (Table 1). Sequences in class one followed the form [ABCDEFxx], where motifs A–F occurred in their position assignments in 99% of the sequences, and any motif A–H could occur with equal probability in either of the final two positions. Sequences in class two followed the form [ABCDEFGx], and those in class three followed the form [ABCDEFxH], where again uppercase letters denote the occurrence or specific motifs in their position assignments in 99% of the sequences, and x denotes the occurrence of any motif with equal probability. For sequences in class four, all of the motifs occurred in their assigned positions with 99% probability, creating a supra-rigid version of the baseline low-entropy stimuli.

Analysis

We used d-prime (d´) to estimate the sensitivity for classification of baseline training song stimuli, and the various test stimuli as given by the equation:

where H gives the proportion of responses to an S+ stimulus, F gives the proportion of responses to an S- stimulus, and z( ) denotes the z-score of these random variables. The measure d´ is convenient because it eliminates any biases in the response rates (e.g. due to guessing) that may vary across individuals and within individuals over time. To gauge the effect of various motif-sequence manipulations during the test sessions, we compared mean performance values (% responses to a given port) for different test-stimulus classes using repeated measures analysis of variance (rmANOVA), and where appropriate used the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test for multiple pair-wise comparisons between mean performance measures for specific stimulus classes. A minimum of 27 (mean = 56) trials per test-stimulus class was available for analysis per subject. In some cases, where appropriate due to small sample size, percent correct data was transformed prior to statistical analyses using the sqrt(arcsine(% correct)). Identical analyses using non-transformed data yielded similar effects. Unless otherwise noted, means are reported along with their standard error.

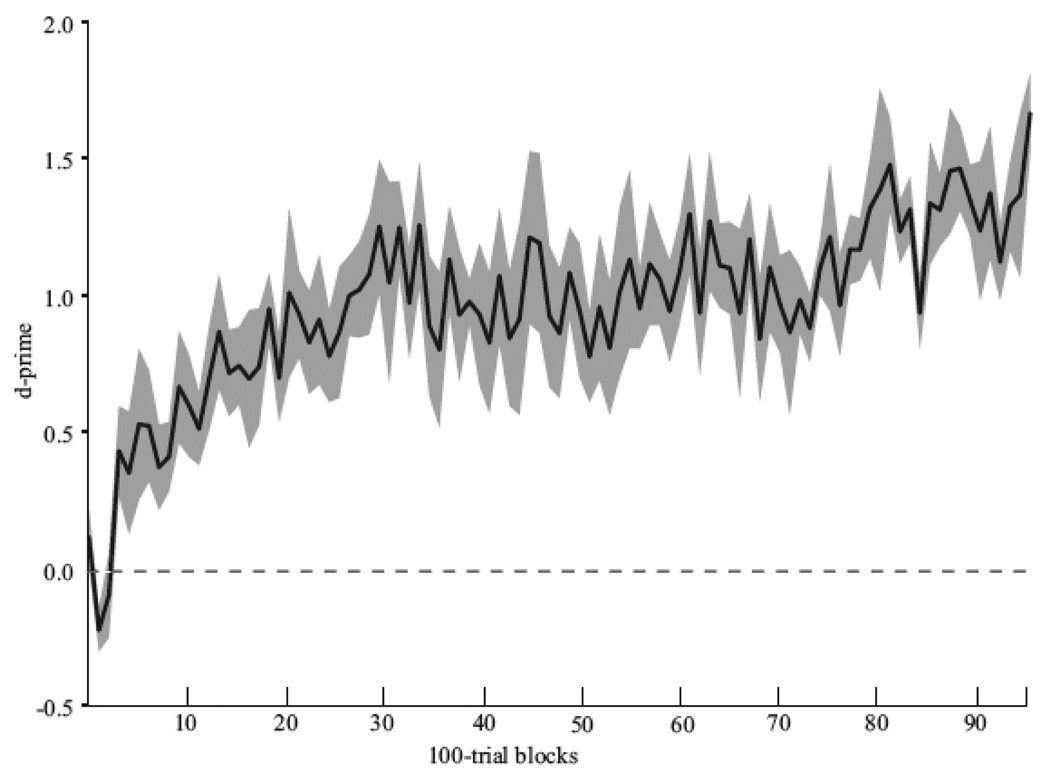

RESULTS

Baseline training

We trained subjects to recognize the baseline high- and low-entropy motif-sequences for 7–15 days. During this time period, progress was monitored daily. The mean acquisition curve for the baseline classification is shown in Fig. 4. Subjects required on average (mean ± sem) 4,700 ± 1,285 trials to reach our performance criterion (d’> 1.0 for 5 consecutive 100-trial blocks). The mean classification accuracy over the last five 100-trial blocks immediately prior to the first transfer session was d’=1.23 ± 0.09. Once each subject was able to reliably classify the high- and low-entropy motif-sequences, we systematically examined this classification ability in a series of tests.

Fig. 4.

Acquisition curve for baseline discrimination of high- and low-entropy baseline training stimuli. The mean d’ (black line) for six subjects over the first 95 blocks (100 trials per block; chance d’ = 0). Standard error values are shown in gray.

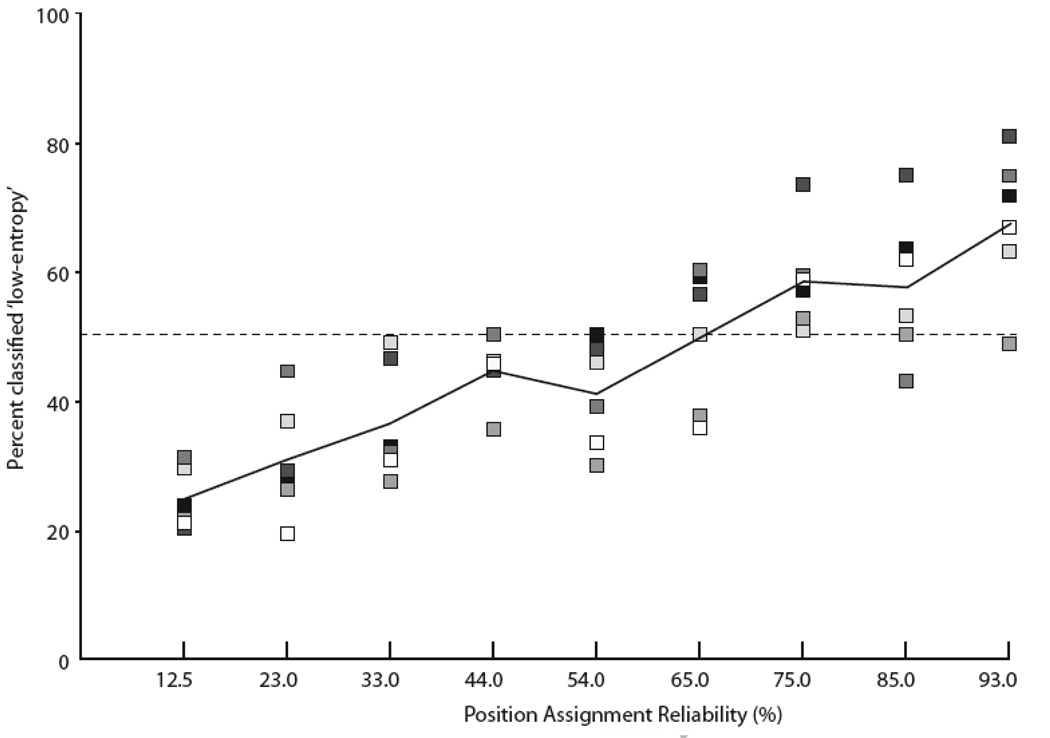

Test Condition One: variation in motif-sequence reliability

In test condition one, we systematically varied the likelihood that a given motif would occur at a given position in the sequence (Table 1). Consistent with the hypothesis that subjects were under strong stimulus control, we observed a significant shift in classification behavior that coincided with changing motif-occurrence probability. As sequences became more static, classification of the sequences as ‘low-entropy’ followed suit (Fig. 5). A regression analysis revealed a significant linear relationship between classification of motif-sequence as either high- or low-entropy and the increasingly static form of the sequences (R = 0.84, F(1, 53) = 122.14, p < 0.001; Fig. 5). Further analyses revealed no significant departures from linearity across the six subjects’ responses (F(1, 7) = 0.71; p = 0.66). These results support the conclusion that starlings effectively exploit subtle changes in probabilities that motifs occur at specific positions (or in motif transitions) for sequence classification. The nature of this sensitivity and its explicit relation to different serial order cues requires further tests.

Fig. 5.

Linear regression between sequence recognition performance and increasing position assignment reliability (R = 0.8375, F(1, 53) = 122.14 , p < 0.001). Shaded squares show the performance of individual subjects (N=6) on each condition, plotted as the percentage of total responses made to the response port associated with the low-entropy sequences. The solid line tracks the mean population responses and the dotted line denotes chance (50%).

Test Condition Two: testing single-motif solution strategies

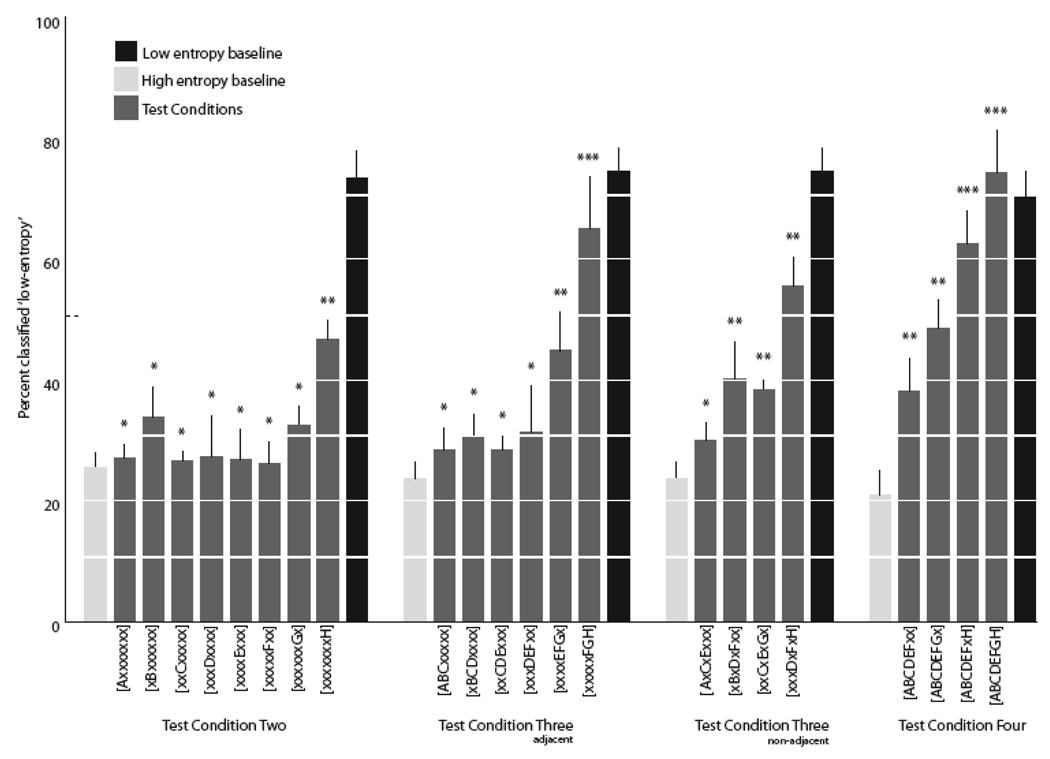

In the second test condition, we explored whether subjects solve the serial recognition task by attending to the presence or absence of a single motif at a specific position (Table 1). The results of test condition two are shown in Fig. 6. Nearly all of the test sequences were treated like the high-entropy baseline sequences, except for those in which the likelihood of motif H occurring in the final position was fixed at 99% (class eight, Fig. 6). Consistent with this, we observed a significant main effect among the eight test stimulus classes in test condition four (F(3,7)=5.09, p = 0.002, repeated measures ANOVA) , supported largely by the pattern of responses to test stimulus class eight. The mean percentage of ‘low-entropy’ responses to the class eight stimuli (46.6 ± 3.4 %) was significantly greater than that given to sequences in most of the other test conditions (p < 0.05 Tukey-Kramer for five of seven comparisons between test stimulus class eight and classes one and three through six). Importantly, the responses to class eight sequences were different from both the high- or low-entropy baseline sequences (p < 0.05 both cases, Tukey-Kramer). In fact, the responses to the class eight sequences did not differ significantly from chance (50%), whereas responses to all of the other test stimulus classes were biased away from chance toward the high-entropy baseline response (p < 0.05, binomial test stimulus classes one through seven compared to chance). Consistent with this bias, the response pattern for test stimulus classes one through seven did not differ significantly from that to the baseline high-entropy sequences (p>0.05 all cases, Tukey-Kramer pair-wise comparisons between test stimulus classes one through seven and the baseline high-entropy responses). This pattern of responding suggests that the regular occurrence of motif H at the terminal position in a sequence holds particular salience, but by itself does not convey sufficient information to account for the recognition of well-patterned (low-entropy) sequences. Indeed, no single position or motif appears to provide this level of information, even though in theory the task is amenable to such a solution strategy. The mean response accuracy for the baseline sequences remained high (d’=1.31 ± 0.16) throughout all of the sessions in test condition two.

Fig. 6.

Mean (±sem) percent ‘low-entropy’ responses given to sequences in test conditions two through four in experiment one (gray bars), along with responses to the high- (light gray) and low-entropy (black) baseline stimuli during each test condition. * indicates significant deviation (p < 0.05) from chance (dotted line), but no significant difference from high-entropy baseline sequences. ** indicates no significant difference from chance levels. *** indicates significant difference from chance (p < 0.05), but no significant difference from low-entropy baseline sequences (see text).

Test Condition Three: multiple-motif solution strategies

Test condition three follows logic similar to that of test condition two except that we increased the likelihood that specific motif triplets occurred in their assigned positions to 99% (Table 1). The results of the third test condition are shown in Fig. 6. Test condition sequences that contained a reliable motif-triplet toward the start of the sequence (e.g. /ABC/, /ACE/, see Table 1 for notation) tended to be classified similarly to the high-entropy baseline sequences. Those containing reliable motif-triplets toward the end of the sequence tended to yield responses closer to chance (50%), or slightly above. Overall, there was significant variation in the patterns of responses to both the six adjacent- and four non-adjacent motif-triplet test stimulus sequences (F(3,5) = 6.97, p = 0.002; F(3,3)=8.35, p = 0.006; main effect in rmANOVA for adjacent- and non-adjacent-test stimulus responses, respectively).

Among the test-stimuli with adjacent-motif triplets, responses to the /ABC/, /BCD/, /CDE/, and /DEF/ sequences were not significantly different than the responses to the high-entropy baseline sequences (p > 0.05, Tukey-Kramer), and were significantly different from chance (p < 0.05, binomial, all cases; Fig. 6). As in the second test condition, the strongest bias for the recognition of well-ordered motif-sequences came from the most terminal positions. Reponses to /EFG/ test sequences were at chance. Responses to the /FGH/ test sequences were significantly above chance (p < 0.05 binomial test), and not significantly different from the low-entropy baseline sequences (Fig. 6).

A similar, though weaker, pattern was observed in the responses to the test stimulus sequences with non-adjacent motif triplets. Responses to the /ACE/ and /CEG/ sequences were not significantly different from the high-entropy baseline sequences (p > 0.05, Tukey-Kramer), but only the responses to the /ACE/ sequences (with non-adjacent motif-triplets) were significantly different from chance (p < 0.05, binomial). Responses to all other sequences with non-adjacent motif triplets (/BDF/, /CEG/ and /DFH/) were not significantly different from chance.

Of all the motif-triplet sequences presented in test condition three, only the sequences in which motifs F, G, and H occurred reliably in the last three positions were treated similarly to the low-entropy baseline sequences. Thus, the presence of the /FGH/ triplet in the correct location can account, in principle, for the recognition of well-patterned baseline motif-sequences.

Test Condition Four: position biases and relative coding of position

In test condition four, we examine directly the bias on terminal motifs by systematically altering the reliability of motifs in the ultimate and penultimate positions while keeping the reliability of motifs at the other positions very high (Table 1). The results of the fourth test condition are shown in Fig. 6.

As predicted, we observed a significant change in response patterns across the stimulus classes in test condition four (F(3,3) = 12.83, p = 0.001, main effect in rmANOVA), with responses moving closer to the low-entropy baseline sequences as motifs in the terminal positions became more reliable in classes one through four (Fig. 6). Subjects gave significantly more ‘low-entropy’ responses to the /–xH/ sequences (see Table 1 for sequence notations) than to /-xx/ sequences (p < 0.05, Tukey-Kramer), and responses to the /–xH/ sequences were significantly above chance (p<0.05, binomial). Thus, again we observed that as information in the final two positions became reliable, recognition of the sequence as ‘low-entropy’ improved significantly. However, neither of the responses to the /–xx/ or /–Gx/ sequences were significantly different from chance. If subjects had relied on only the last two motifs to solve the recognition task, then the /–xx/ sequences should be well below chance.

A similar pattern was observed when comparing these test stimulus responses to those for the baseline sequences. The responses to the /–xx/ and /–Gx/ sequences were significantly lower than responses to the low-entropy baseline stimuli during the same sessions (p < 0.05 both cases, Tukey-Kramer following rmANOVA using baseline and test stimulus responses, F(3,5) = 23.72, p < 0.0001, Fig. 6). In contrast, responses to the /–xH/ sequences did not differ significantly from those for the low-entropy baseline stimuli.

Comparison Between Test Conditions Three and Four

The performance on specific sequences presented in test conditions three and four support the conclusion that starlings have access to information as far back as four motifs before the end of the sequence. In test condition three, otherwise random sequences that ended reliably with the sequence /FGH/ were treated similarly to the low-entropy baseline sequences, but the mean percentage of ‘low-entropy’ responses to these sequences (65.13 ± 8.57) was slightly below that for the actual low-entropy baseline stimuli (74.53 ± 3.86) presented during the same sessions (Fig. 6). In test condition four, sequences in which all eight motifs (including F, G, and H) appeared in their position assignments 99% of the time elicited a high mean percentage of ‘low-entropy’ responses (74.35 ± 6.91), which was slightly above that for the actual low-entropy baseline stimuli (70.30 ± 4.27) presented during those sessions. To directly compare responses between these specific test stimuli (presented in different sessions and conditions), we expressed performance for each test stimulus as a proportion of the corresponding (contemporaneous) baseline performance. The difference in performance between these test stimuli, [xxxxxFGH] and [ABCDEFGH], was significant (t=-3.98, p =0.02, paired t-test). Because the only difference between these test stimuli is the sequence of motifs that precedes the terminal FGH triplet, we conclude that recognition is improved by the reliability of the motifs in at least the last four positions of the sequence.

DISCUSSION

The results of experiment one demonstrate that starlings are capable of recognizing differences in the temporal sequencing of song motifs, and do so by coding the absolute position of motifs (or motif transitions) with respect to the end of the sequence. All of the subjects quickly learned to classify ‘low-entropy’ and ‘high-entropy’ motif sequences which varied only in the likelihood that a given motif would occur at a given location in each sequence. It is already known that starlings are capable of perceiving complex motif patterns (Gentner et al., 2006), and show evidence of auditory plasticity (Ball, Sockman, Duffy, & Gentner, 2006; Buchanan, Spencer, Goldsmith, & Catchpole, 2003; Gentner & Margoliash, 2003). In the present study, we asked if starlings could detect subtle changes in motif-occurrence probabilities in the absence of abstract patterning rules, by using only the relative or absolute position information for specific motifs.

We find that starlings’ sensitivity to the temporal sequence of motifs is quite good. Parametric alterations in the reliability of motif occurrence that span the range between the baseline high- and low-entropy sequences lead to a monotonic and roughly linear change in the subjects’ performance. As reliability increased across all sequence positions (test condition one), subjects were increasingly likely to respond to a given sequence as if it was a low-entropy baseline sequence (Fig. 5). Subjects did not treat all sequences above or below a “threshold” of orderliness as always either low- or high-entropy. Thus, the starlings’ perceptual sensitivity to motif sequencing is more continuous than categorical.

There are, of course, multiple solution strategies that could give rise to the observed performance in test condition one. Among the most parsimonious is one in which starlings simply listened for a specific motif at a specific location in the sequence. The results of test condition two are, however, inconsistent with this simple solution strategy. When the occurrence of any single motif at its assigned position was made highly reliable (99%) amid otherwise randomly occurring motifs, subjects almost always treated the sequence as if it was a high-entropy (random) sequence. The only exception to this was if the reliable motif was the last one in the sequence (motif H). In that case, performance was shifted away from the ‘high-entropy’ response pattern, but was not significantly different from chance. Although the terminal position in the sequence appears to hold greater salience than any other position, no single motif in any position can fully predict a subject’s response. Instead, subjects must be attending to multiple motifs, and by extension to their temporal sequencing.

In test conditions three and four, we investigated the boundaries on the temporal sequencing information that starlings had acquired during training. We found that while the penultimate and ultimate positions in a sequence held the strongest control over the decision about whether or not a sequence was well-patterned (i.e., ‘low-entropy’), significant influences could be traced as far back as the fourth motif from the end of the sequences. When the last two motifs vary randomly in an otherwise reliable sequence, subjects responded at chance (Fig. 6). Thus, the final two positions are necessary, but not sufficient, for classification of sequences as low-entropy. Had the last two motifs provided sufficient information, responses to these test sequences would be equivalent to responses for corresponding high-entropy sequences. Instead, starlings must be gaining information from motifs that occur before the last two sequence positions. Likewise, starlings are better able to recognize a sequence as low-entropy if all of the motifs in a sequence occur at their assigned position with high reliability compared to sequences in which only the last three motifs are made reliable. This latter effect suggests that starlings are sensitive to sequence information spanning at least the four terminal motifs.

Support for the notion that starlings retain information from the four initial motifs in the sequences comes from comparisons between the non-adjacent motif-triplet sequences in test condition three and sequences in test condition two. For example, when motif F occurred reliably in position 6 among otherwise random motifs, subjects responded as if the sequence was a high-entropy baseline stimulus (Fig. 6). When reliable occurrences of motif F (in position 6) were coupled with reliable occurrences of motifs B and D (in positions 2 and 4, respectively), responses were significantly different from those given to the high-entropy baseline sequences (Fig. 6). Thus, motifs at position 2 and/or 4 can influence behavior, and information from reliable early-sequence cues can combine constructively with that from reliable late-sequence cues to alter behavior. These results support the conclusion that integration of motif reliability can span across non-adjacent motif positions, but this ability deserves further targeted investigation.

Based upon these results we can assign initial parameters to the working memory capacity of starlings under these specific task constraints. The minimum duration of working memory for the present task is three motifs. When fewer than three well-patterned motifs were given to the birds, performance suffered significant declines relative to baseline. The maximum duration of working memory in this context remains unknown, and so awaits future study. For now, we can safely say that starlings are capable of using information from at least four, and perhaps as many as six, sequential motifs to control behavior on a single trial.

EXPERIMENT TWO

In the second experiment, we tested two hypotheses concerning how information was stored in working memory during experiment one. Specifically, the structure of both the training and testing stimuli in experiment one included relative and absolute position cues. In the second experiment we dissociate these cues. The results have important theoretical ramifications for addressing comparative questions about the structure of working memory in processing complex acoustic communication signals.

METHODS

Subjects

Eleven starlings, divided into four groups, served as subjects in experiment 2. The first three groups each contained three starlings and the fourth group contained two birds. Three subjects from experiment one, made up the first group. All other birds were naïve to the stimuli and behavioral apparatus.

Apparatus

The apparatus was the same as that used in experiment one.

Procedures

In three separate training conditions, we examined whether starlings could learn to recognize different motif-sequences that contained only relative position cues. The shaping and training procedures were identical to those used for baseline sequence recognition in experiment one.

Stimuli

We constructed the three sets of motif-sequences for experiment two (one set for each condition). In each set we used the same eight motifs presented in experiment one (Fig. 2). For each of the three conditions we created two classes of eight-motif-sequences that subjects had to learn to recognize. To remove absolute position cues from the motif-sequences while leaving relative position cues intact, we allowed the sequence presented on any given trial to start with a randomly selected motif and then to wrap back to the start of the sequence, as necessary to play each motif. For example, a sequence of the form [ABCDEFGH], where letters represent different motifs, could be heard on different trials as [ABCDEFGH], [BCDEFGHA], [CDEFGHAB], [DEFGHABC], [EFGHABCD], etc. The “wrapping playback” was used for all three training conditions in experiment two. Across the three training conditions, we attempted to simplify the sequences to make acquisition easier.

Training condition one

Except for the wrapping playback, the temporal structure of the motif-sequences used for the first training condition was identical to that used for baseline training in experiment one. As in experiment one, we created two classes of sequences, a ‘low-entropy’ class in which the serial ordering of eight motifs was largely static, and a ‘high-entropy’ class in which the serial ordering of the same eight motifs was maximally random. Unlike experiment one, the sequence presented on any trial could start with any motif.

For low-entropy sequences, which took the basic form [ABCDEFGH], each motif occurred in its assigned position 93% of the time (Table 2). Thus, each canonical transition, /AB/, /BC/, /CD/, /DE/, /EF/, /FG/, /GH/, /HA/, had a 93% chance of occurring and the seven other possible transitions (given a specific motif) had a 1% chance of occurring. In the high-entropy sequences, all transitions were equally probable (Table 2). Each explicit sequence was generated online prior to each trial. The starting motif (A-H) on each trial was selected randomly with uniform probability from all eight motifs. Because the sequence on a given trial could start with any motif, the transition from motif H to A occurred commonly (see Table 2). As in experiment one, motif repetitions were possible within a given trial.

Table 2.

Motif-sequence designs for experiment two. Occurrence likelihoods follow the same conventions as Table 1

| Stimulus class | Motif-sequence form |

Occurrence likelihood (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Training condition one: Low-entropy |

[ABCDEFGH] | 93 |

| [BCDEFGHA] | 93 | |

| [CDEFGHAB] | 93 | |

| [DEFGHABC] | 93 | |

| [EFGHABCD] | 93 | |

| [FGHABCDE] | 93 | |

| [GHABCDEF] | 93 | |

| [HABCDEFG] | 93 | |

| Training condition one: High-entropy |

[ABCDEFGH] | 12.5 |

| [BCDEFGHA] | 12.5 | |

| [CDEFGHAB] | 12.5 | |

| [DEFGHABC] | 12.5 | |

| [EFGHABCD] | 12.5 | |

| [FGHABCDE] | 12.5 | |

| [GHABCDEF] | 12.5 | |

| [HABCDEFG] | 12.5 | |

| Training condition three: Low-entropy 1 |

[ABCDEFGH] | 100 |

| [BCDEFGHA] | 100 | |

| [CDEFGHAB] | 100 | |

| [DEFGHABC] | 100 | |

| [EFGHABCD] | 100 | |

| [FGHABCDE] | 100 | |

| [GHABCDEF] | 100 | |

| [HABCDEFG] | 100 | |

| Training condition three: Low-entropy 2 |

[EGBDACHF] | 100 |

| [GBDACHFE] | 100 | |

| [BDACHFEG] | 100 | |

| [DACHFEGB] | 100 | |

| [ACHFEGBD] | 100 | |

| [CHFEGBDA] | 100 | |

| [HFEGBDAC] | 100 | |

| [FEGBDACH] | 100 | |

Training condition two

For the second training condition, we created another set of stimuli very similar to the set in condition one, except that a given motif was chosen for a given position in the low-entropy sequences 100% of the time. We also added a 100-ms silent gap to both the high- and low-entropy sequences to act as a ninth “motif”. To compensate for the addition of this ninth element to each sequence the probability that a given element was chosen for a given position in the high-entropy sequences was adjusted to 11.1%. As in training condition one, the starting motif (A-H) on each trial was selected randomly with uniform probability from all eight motifs, and the sequence wrapped as necessary during playback.

Training condition three

For the third training condition, we removed even more variability from the motif-sequences. Instead of having one low-entropy and one high-entropy class, we constructed two low-entropy classes. Within each class, a given motif was chosen for a given position 100% of the time. Although the same eight motifs were used to construct the sequences in each class, there were no shared transitions between the two classes (Table 2). This strategy effectively created two static sequences, which on any given trial could start at any one of eight different positions, and the subjects’ task was to recognize two different low entropy sequences based only on relative position cues. As in training conditions one and two, the starting motif (A-H) on each trial was selected randomly with uniform probability from all eight motifs, and the sequence wrapped as necessary during playback.

Analysis

We used d’ to assess recognition of the motif sequences in the various classes. During the transfer from experiment one to experiment two, we measured d’ over 100-trial blocks. To assess learning over the duration of different training conditions we calculated d’ over 200-trial blocks, and used repeated measures ANOVA with exposure as a within subjects variable and training condition as a between subjects variable.

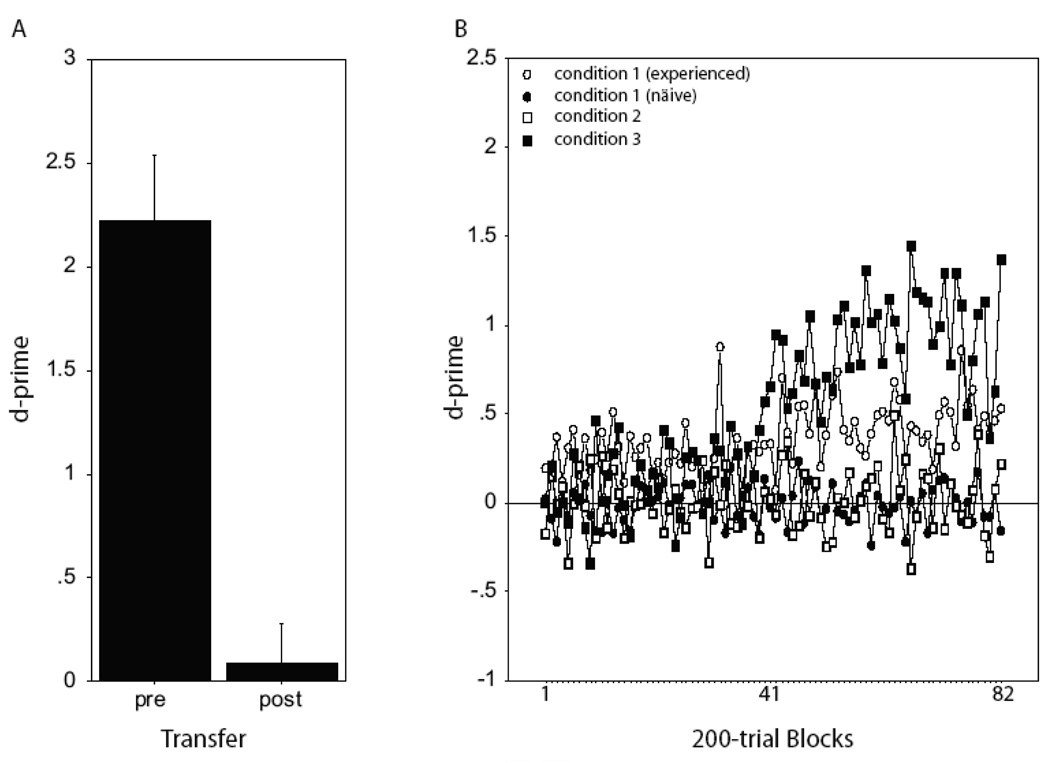

RESULTS

To test if starlings could recognize motif sequences that contained only relative position cues, three birds from experiment one (where relative and absolute position cues were available) were presented with stimuli from the training condition one (in which absolute position cues were unavailable). Performance across this transfer dropped significantly (Fig. 7a), from a mean (± sem) d’ of 2.22 ± 0.32 to 0.09 ± 0.19 (p = 0.02, paired t-test), and performance after the transfer was not significantly above chance (p=0.676, t-test). This suggests that birds were using absolute position information to recognize the sequences in experiment one.

Fig. 7.

Experiment two performance. (A) Mean (± sem) d’ in the five 100-trial blocks immediately prior to (pre) and the first block after (post) transfer from motif sequences with both relative and absolute position cues to sequences with only relative position cues. (B) Acquisition curves plotting the mean (± sem) d’ values over the course of training (84, 200-trial blocks) during each of the three training conditions in experiment two.

To assess the learnability of motif sequences that contain only relative position cues, we trained three groups of naïve birds, each on one of the three different training conditions, and kept two of the experienced birds on the stimuli in training condition one to which they had just transferred. Neither the naïve nor experienced group learned to recognize the motif-sequences in training condition one or two. The birds exposed to training condition three did eventually learn to recognize the motif sequences (Fig. 7b). After 164 100-trial blocks of training (the largest number of blocks from which there are data from all subjects) the mean d’ (over the last 2 blocks, ± sem) for naïve subjects in the first and second condition (N=3, both conditions) was −0.17 ± 0.12 and 0.21 ± 0.17, respectively, while that for experienced subjects (N=2) in the first training condition was 0.52 ± 0.30. In contrast, after 164 100-trial blocks, subjects in training condition three (N=2), where the task was to recognize two fixed but different sequences of the same eight motifs, showed a mean d-prime (over the last 2 blocks) of 1.36 ± 0.52.

Examining the performance across training from all four groups of birds (Fig. 7b), we observed a significant main effect of learning (F(81, 486) = 2.89, p<0.0001, rmANOVA) and a significant interaction between learning and training condition (F(243,486) = 1.93, p <0.0001). Among the three groups of birds exposed to training conditions one and two, however, there was no significant change in performance with training when either all subjects from these groups were considered together (F(7, 81) = 1.10, p = 0.27, rmANOVA main effect of training) or when the three groups were treated independently (F(2, 162) = 1.16, p = 0.13, rmANOVA interaction between condition and training; Fig. 7b). Even for those birds trained extensively on the motif-sequences in conditions one and two (one subject per condition), performance remained poor. The mean d’ after 225 100-trial blocks on condition one was 0.12 ± 0.11, and after 716 100-trial blocks on condition two was 0.12 ± 0.09 (means represent average of last 5 blocks). In contrast, subjects in training condition three did show a significant increase in performance with training over the first 82 200-trial blocks (F(1,81)=2.10, p = 0.0005, rmANOVA, Fig. 7b), indicating that consistent learning occurred in this group, albeit after much training (>40 200-trial blocks, Fig. 7b). We note as well that one of the experienced birds did appear to improve marginally over the course of training, reaching a mean d-prime of 0.66 ± 0.15 over the final five of 164 100-trial blocks. While not indicative of particularly strong recognition, this level of performance is significantly better than that expected by chance (t(4) = 4.52, p = 0.012, one sample t-test), and did improve slightly with extensive training reaching 0.98 ± 0.15 and 1.10 ± 0.11 after 255 and 445 100-trial blocks, respectively. The source of the individual differences between the experienced birds is not clear. In any case, learning with only relative position cues is possible, but not easy.

DISCUSSION

The results of experiment two suggest that temporal sequence recognition and classification in the present study is driven primarily by information about the absolute position of motifs in each sequence. When subjects transferred from sequences in experiment one, where both absolute and relative position information were available, to sequences in which the only relative position cues were available, recognition fell to chance levels. Moreover, almost all subjects failed to learn to recognize a single, reliably patterned sequence of eight motifs against a backdrop of highly variable sequences built from the same eight motifs using only relative position information. We found that increasing the reliability with which a specific motif occurred in a relative position from 93% to 100% did not aid learning, nor did adding a silent gap between two of the motifs in the sequences. We predicted that the silence in the latter case would act as a salient edge or stable locus for attention and so help to elucidate the relative position information in the sequences. This did not happen. Therefore, we conclude that sequences without absolute position information are very difficult for starlings to learn.

Although strong, the bias for absolute position information is not unconditional. Experiment two shows that under some circumstances (perhaps with sufficient experience in the case of one bird), or when stimuli are structured appropriately, starlings can use relative position cues to correctly recognize sequentially patterned strings of motifs. When starlings were presented with two dissimilar, fixed-transition sequences, learning based on relative motif position was observed. In principle, these kinds of two-alternative choice recognition tasks are amenable to solution strategies that rely on the recognition of only one of the two stimulus classes. That is, starlings might use a rule that says, anthropomorphically, “peck left if I hear a class one stimulus, peck right if I hear anything else”. This simple solution strategy cannot, however, explain the present results. Instead, recognition performance is improved by changes in the sequence reliability for both classes of stimuli. This suggests that at least portions of both sequences are learned. Consistent with this, the results from more complex pattern recognition studies (Gentner et al., 2006) also suggest that starlings can acquire at least two patterns simultaneously.

The differences in learnability between the first two and the third condition are consistent with a strong role for proactive interference across trials. In principle, this interference could come from motif identity and/or motif transitions. Because we used a very small number of items (8) and almost all of them appear on every trial (sometimes in multiple positions), we are likely to get high proactive interference for motif identity across trials. Any effects of interference from motif identity are constant across all conditions, however, and so cannot explain the improved learning in condition three. The only source of interference that varied in condition three was that from the motif transitions, which is ameliorated in this case because there are no common motif transitions between the sequences in either class. We note, however, that the potential interference from overlapping transitions across stimulus classes is not very large. On average, roughly 10% of the transitions in the high-entropy sequences are likely to overlap with those in the low-entropy sequences. Thus, if proactive interference of motif transitions is the source of the poor recognition performance in the first two conditions the results constitute evidence for very high sensitivity to motif-transitions across trials. One way to test this interference theory directly is to train starlings with a high-entropy class of motif-sequences that is still variable, but that has no transitions in common with sequences in the opposing class, thus removing any proactive interference from the transitions. In any case, learning temporal sequences defined only by the relative structure of acoustic objects is possible in starlings, albeit in a slow and not very flexible way.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The current study explored the mechanisms underlying working memory for auditory sequences in European starlings. Theoretical arguments have long contested whether serial learning involves associative or “higher” processes (Lashley, 1951), and contemporary theories of absolute or relative serial position coding in human working memory derive directly from these ideas (Henson, 1998). Our results demonstrate that starlings can readily discriminate the varying order of motifs in a natural song-like sequence, and do so preferentially via absolute positional cues. We also show that starlings can use relative position cues, but only under restricted conditions when reliable motif transitions define two specific sequences.

The present results differ from those reported for working memory (WM) tasks in other species and modalities. In particular, there are strong differences between species in the time course for primacy and recency effects in visual modalities, but all recall curves show the same general forms. At short recall delays recency dominates, while at long delays primacy effects are strongest. At intermediate delays, humans and other animals recalling serial lists of visual objects show both primacy and recency effects giving rise to the classic u-shaped serial position functions (Wright, Santiago, Sands, Kendrick, & Cook, 1985). The opposite transition between primacy and recency is seen for auditory lists. At short delays, recall for initial items in the list is strongest and at long delays recall for terminal items is strongest. The visual data can be accounted for by decay processes in WM and consolidation into long-term memory as delay increases, but the auditory data cannot. Instead, it has been proposed that the retrieval failure that gives rise to the auditory serial position function is the result of interference. By this account proactive interference is strong just after a list of auditory items is presented (i.e. for short delays) causing retrieval failure and depressing recognition of items at the end of the list. Over longer delays following a list of auditory items, the effects of proactive interference diminish while retroactive interference strengthens, leading to retrieval failures on the initial list items.

The strong role of interference in shaping the serial position function is supported by studies in rhesus macaques (Wright & Rivera, 1997), and we suggest an important role of interference in constraining performance in experiment two. However, the interference-based account of serial auditory recall does not fully explain our present results. We see a clear bias for responses driven by the terminal motifs in a sequence in experiment one. Strict interference models would suggest that with no response delay, as was the case in the present task, proactive interference should be very high and that this should lead to responses dominated by motifs from the start of the sequences. Yet, we see the exact opposite. One should not take this to mean, however, that interference-based accounts of serial recall are necessarily incorrect. There are a multitude of methodological differences between the tasks used to generate serial position curves for lists of auditory items and the procedures used in the present experiments, and these alone make direct comparisons difficult. We simply wish to point out that a clear departure from the expected outcome of interference-based accounts is observed. This may be due to methodological constraints of the present task, or may reflect more fundamental aspects of the memory processes that underlie the sorts of sequentially patterned, ecologically relevant, signals used here.

Having provided a clear initial demonstration of working memory for sequentially patterned acoustic communication sequences in this species, it will be important for future work to explore these abilities in greater detail and in relationship to the operant parameters used for initial training. Future work must consider, during both acquisition and asymptotic recognition, the role of various delay intervals between the sequence and the response, and the role of restricting the informative portions of the sequence to the initial and middle sections. It is important to note, however, that by itself, the emphasis on terminal motifs (or any other specific motifs in the stimulus set) is not crucial to the central claims of this paper. We are concerned primarily with the bounds of working memory and the character of the information contained therein. The fact that some of that information is carried by motif H may well reflect the structure of the task, but the carrier of the information is not our primary concern. Given the temporal nature of the song stimuli and the appetitively motivated conditioning procedures we use, it would be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to remove all differences in the temporal delays between specific motifs and the reinforcer. This inherent structure highlights some of the difficulty in studying comparative mechanisms of serial working memory for natural, temporally sequenced, auditory signals. In any case, the dominance of recency over primacy has substantial precedent in the comparative literature (e.g. Thompson and Herman, 1977), and that, consistent with our results, strong primacy effects are more rare (Wright & Rivera, 1997). It may be that proactive/retroactive interference models do not apply to all auditory memories, or that the complexity of the pattern processing capacities described in the present task engaged separate systems, with their own memory constraints (e.g. Fountain et al., 1984), that were not engaged by previous serial list recall studies (Wright & Rivera, 1997).

Chaining and Positional Codes

The difficulties in understanding serial behavior and learning using strict associative chaining theories (Skinner, 1934) have long been known, and early discussions of these questions (e.g. Lashley, 1951) mark the birth of the cognitive revolution in human psychology. Questions regarding the use of positional and associative chaining strategies have also dominated the work in non-human studies of serial recognition behavior. Although some serial order behaviors in pigeons and mammals are easily explained by chaining strategies (Wiesman et al., 1980; Balleine et al 1995), others, particularly those studied with “simultaneous chaining” procedures are not (Terrace, 1986, 1987; Straub & Terrace, 1981; D’Amato & Colombo, 1988). In the simultaneous chain procedure animals are taught to produce a series of responses to simultaneously presented, randomly arrayed, visual stimuli, and reinforced only when a correct sequence of responses to different stimuli is produced. Simultaneous chains have been used to study serial order representations in pigeons and primates (Straub & Terrace, 1981; D’Amato & Colombo, 1988). In both species, the use of positional information to learn and recall serially ordered lists of visual stimuli is now well supported (Terrace, 1987; Chen, Swartz, Terrace 1997; D’Amato & Colombo, 1988). In primates, positional information can extend beyond knowledge of serial ordering of explicit items at each location to capture ordinal position (Chen Swartz, Terrace, 1997; Terrace 2003; Orlov, Yakolev, Hochstein & Zohary, 2000; Orlov, Yakolev, Amit, Hochstein & Zohary 2002). The present results, indicate a clear bias for positional over associative chaining (relative) information, and show that the latter offers a limited solution strategy available only under very specific conditions. These results fit very well with the large body of work on serial order in visual tasks, and so extend general models of serial order processing and recall into a natural behavioral context tied to vocal communication, and across a broad taxonomic range.

The current design is inspired by the natural, temporal organization of most acoustic communication signals, including starling song, and starlings use the natural temporal regularities in song as an aid to individual vocal recognition (Gentner & Hulse, 1998). Here, we simply gave subjects a string of motifs, let them solve the task how they wished, and then probed the bounds of their working memory for the chosen solution strategy. The task and stimuli we chose for the current study are closely derived from more naturalistic vocal recognition studies conducted in the lab using a variety of techniques and dependent measures (Gentner, 2008; Gentner & Hulse, 1998; 2000; Gentner & Margoliash 2003). Whether or not we artificially biased the use of absolute position with the present stimuli and task, we cannot say. Such a conclusion awaits further studies using different designs and stimuli. In any case, starlings are likely to have access to both kinds of sequence information under more natural settings. A priori, we had no clear reason to bias subjects against relevant information in the terminal position, and it could have easily turned out that the first motif in the sequence was “biased.” Previous studies of working memory in European starlings report memory persistence for tonal signals between 4 to 20 seconds in a delayed non-matching-to-sample task (Zokoll et al., 2007, 2008), and our stimuli, although more complex than those previously tested, fall well within this range. Given the previous evidence that sensitivity to motif-sequence aids song recognition in starlings (Gentner & Hulse, 1998), our current findings serve as a potential learning mechanism through which this natural behavior is accomplished. Thus, the working memory abilities observed in the present study are not likely to be the artifacts of arbitrary laboratory conditions. Whereas most preceding work on serial pattern learning, particularly in the auditory domain, has used stimuli with little or no ecological value such as sine tones, our task has a clear analogue to natural song-driven behaviors.

The observed bias for absolute position cues in working memory has important theoretical implications for understanding animal communication signals. The temporal structure of animal communication signals, including starling song (Gentner & Hulse, 1998), can be described in terms of finite state automata (Chatfield & Lemon, 1970; Dobson & Lemon, 1978; Lemon & Chatfield, 1971; Lemon & Chatfield, 1973; Lemon, Dobson, & Clifton, 1993; c.f. Suzuki, Buck, & Tyack, 2006). These descriptions are fundamentally associative in the sense that they only model the relative probabilities of transitioning from one communication element (e.g. motif) to the next. Although capable of modeling much of the structure in such signals, they clearly do not reflect the perceptual strategies that animals use to learn or recognize such signals. Instead, the processing mechanisms are inherently hierarchical in that they involve representation of both the item and its appropriate serial position. Previous pattern-learning data from starlings (Gentner et al., 2006) are consistent with this kind of hierarchical representation. Models for the structure of animal communication signals, should take hierarchical organization into account.

Associative chaining is inefficient in many ways (Henson, 1998) and is theoretically cumbersome for events closely spaced in time. If working memory in serial processing evolved in humans as an aid to language acquisition, as suggested by some (Baddeley et al., 1998), then selection forces are likely to have acted on the sorts of common positional coding mechanisms described here. Despite their logical parsimony, associative codes for serial position may be difficult to instantiate biologically or even non-adaptive. The sensitivity of European starlings to absolute and relative positional cues suggests that this species of songbird can serve as a comparative model for exploring the relationship between these coding strategies, and more generally in understanding the role of auditory working memory in a system amenable to invasive neuroscience methods. Future work should explore how absolute and relative positional cues are integrated together in online processing of sequences of acoustic objects in working memory at this level.

Acknowledgements

NIH DC008358 supported this research. The authors thank John Wixted, Scott McKinney, Timothy Cox and Samantha Barnard for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adret-Hausberger M, Jenkins PF. Complex organization of the warbling song in starlings. Behaviour. 1988;107:138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Gathercole S, Papagno C. The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychol Rev. 1998;105(1):158–173. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball G, Sockman K, Duffy D, Gentner T. A Neuroethological Approach to Song Behavior and Perception in European Starlings: Interrelationships Among Testosterone, Neuroanatomy, Immediate Early Gene Expression, and Immune Function. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 2006;36:59–121. [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Garner C, Gonzalez F, Dickinson A. Motivational control of heterogeneous instrumental chains. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1995;21(3):203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Boutla M, Supalla T, Newport EL, Bavelier D. Short-term memory span: insights from sign language. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(9):997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KL, Spencer KA, Goldsmith AR, Catchpole CK. Song as an honest signal of past developmental stress in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;270(1520):1149–1156. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield C, Lemon RE. Analysing sequences of behavioral events. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1970;29:427–445. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(70)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Swartz KB, Terrace HS. Knowledge of the ordinal position of list items in rhesus monkeys. Psychological Science. 1997;8(2):80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R. Order error in immediate recall of sequences. Journal of Verbal Learning &. 1965;4(3):161–169. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato MR, Colombo M. Representation of serial order in monkeys (Cebus apella) J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1988;14(2):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson CW, Lemon RE. Markov sequences in the songs of american thrushes. Behaviour. 1978;68(1–2):86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK. Birdsong and human speech: common themes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neuro. 1999;22:567–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eens M, Pinxten R, Verheyen RF. Organization of Song in the European Starling - Species- Specificity and Individual-Differences. Belgian Journal of Zoology. 1991;121(2):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Endress AD, Nespor M, Mehler J. Perceptual and memory contraints on language acquisition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(8):348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain SB, editor. The Structure of Sequential behavior. 2006. [Google Scholar]; Wasserman Edward A, Zentall Thomas R. Comparative cognition: Experimental explorations of animal intelligence. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Fountain SB, Henne DR, Hulse SH. Phrasing cues and hierarchical organization in serial pattern learning by rats. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1984;10(1):30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ. Temporal scales of auditory objects underlying birdsong vocal recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;124(2):1350–1359. doi: 10.1121/1.2945705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ, Fenn KM, Margoliash D, Nusbaum HC. Recursive syntactic pattern learning by songbirds. Nature. 2006;440(7088):1204–1207. doi: 10.1038/nature04675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ, Hulse SH. Perceptual mechanisms for individual vocal recognition in European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris. Animal Behaviour. 1998;56:579–594. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ, Hulse SH. Perceptual classification based on the component structure of song in European starlings. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;107(6):3369–3381. doi: 10.1121/1.429408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ, Margoliash D. The neuroethology of vocal communication: perception and cognition. Vol. 16. Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]