Abstract

A structurally-diverse series of carboxylate derivatives based on the 1, 2, 5-thiadiazolidin-one 1, 1 dioxide scaffold were synthesized and used to probe the S’ subsites of human neutrophil elastase (HNE) and neutrophil proteinase 3 (Pr 3). Several compounds are potent inhibitors of HNE but devoid of inhibitory activity toward Pr 3, suggesting that the S’ subsites of HNE exhibit significant plasticity and can, unlike Pr 3, tolerate various large hydrophobic groups. The results provide a promising framework for the design of highly selective inhibitors of the two enzymes.

Introduction

The human neutrophil elastase (HNE) is believed to play an important role in the pathophysiology of an array of inflammatory diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),1 cystic fibrosis,2 acute respiratory distress syndrome,3 ischemia/reperfusion injury,4 and others.5–6 COPD is a multi-factorial disorder that is characterized by an oxidant/anti-oxidant imbalance,7–8 alveolar septal cell apoptosis,9–10, a protease/anti-protease imbalance,1,11 and chronic inflammation.7,12 The confluence and interplay of multiple processes and mediators have gravely hampered efforts aimed at elucidating the molecular mechanisms and biochemical events which underlie the initiation and progression of COPD.13

An array of proteases, including serine (neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3), cysteine (cathepsin S) and metallo- (MMP-12) proteases released by neutrophils, macrophages and T lymphocytes that are capable of degrading lung elastin and other components of the extracellular matrix,14 have been implicated in COPD. Elucidation of the pathogenic mechanisms in COPD and, specifically, the role each protease plays in the disorder, would pave the way toward the development of novel COPD therapeutics.15

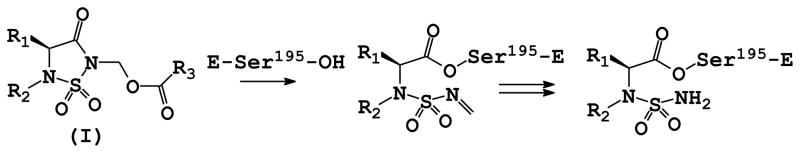

We have previously demonstrated that the 1, 2, 5 – thiadiazolidin-3-one 1, 1 dioxide scaffold is a powerful and versatile core structure that can be used in the design of potent mechanism-based inhibitors of serine proteases that exploit multiple binding interactions on either side of the scissile bond.16 X-ray crystallography and ESI-MS studies have furthermore demonstrated that inhibitor (I) inactivates HNE via a mechanism that involves the initial formation of a relatively stable acyl enzyme that incorporates in its structure a conjugated sulfonyl imine functionality. Subsequent slow reaction with water leads to the formation of one or more acyl enzymes of variable stability (Figure 1). We describe herein the results of exploratory studies related to the utilization of inhibitor (I) to probe the S’ subsites17 of HNE and human proteinase 3 (Pr 3) that shares 54% sequence similarity with HNE.18

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of inhibitor (I).

Chemistry

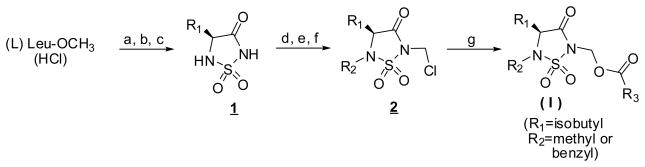

Compounds 3-18 were synthesized as shown in Scheme 116,19 starting with (L) leucine methyl ester hydrochloride. The heterocyclic ring 1 was readily assembled in three steps as previously described20 and then further elaborated to yield N-chloromethyl intermediate 2 (R1 = isobutyl, R2 = methyl or benzyl) which was transformed into the desired compounds via reaction with sodium iodide in acetone and subsequently with a carboxylic acid in the presence of DBU.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of inhibitor (I)

Reagents and conditions: a) ClSO2N=C=O/t-BuOH/TEA; b) TFA; c) NaH/DMF; d) PhSCH2Cl/TEA; e) NaH/DMF then methyl iodide or benzyl bromide; f) SO2Cl2; g) NaI/acetone then R3 COOH/DBU/CH2CI2

Biochemical studies

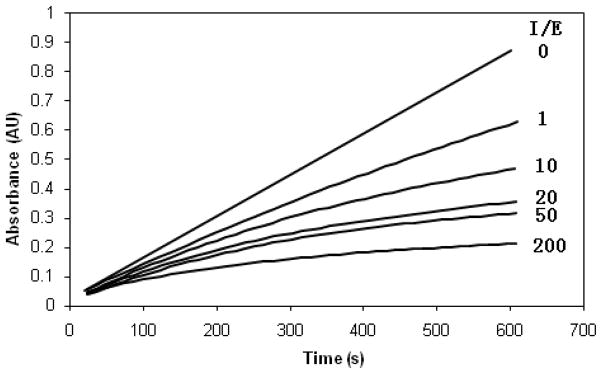

The inhibitory activity of compounds 3-18 was determined using the progress curve method.21 Typical progress curves for the hydrolysis of MeOSuc-AAPV-pNA by HNE in the presence of inhibitor 18 are shown in Figure 2. Control curves in the absence of inhibitor were linear. The release of p-nitroaniline was continuously monitored at 410 nm. The pseudo first-order rate constants (kobs) for the inhibition of HNE by 18 as a function of time were determined according to Equation 1, where A is the absorbance at 410 nm, vo is the reaction velocity at t = 0, vs is the final steady-state velocity, kobs is the observed first-order rate constant, and Ao is the absorbance at t = 0. The kobs values were obtained by fitting the A versus t data to Equation 1 using nonlinear regression analysis (SigmaPlot, Jandel Scientific). The second order rate constants (kinact/KI M−1 s−1) were then determined by calculating kobs/[I] and then correcting for the substrate concentration using Equation 2. The apparent second-order rate constants (kinact/KI M−1 s−1) were determined in duplicate and are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Progress curves for the inhibition of human neutrophil elastase (HNE) by inhibitor 18. Absorbance was monitored at 410 nm for reaction solutions containing 10 nM HNE, MeOSuc-AAPV p-nitroanilide (105 μM), and the inhibitor at the indicated inhibitor to enzyme ratios in 0.1 M HEPES buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.25, and 2.5% DMSO. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C and reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme.

Table 1.

List of Inhibitors and Inhibitory Activity toward Human Neutrophil Elastase

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R3 | R2 | kinact/KI (M−1s−1) |

| 3 |  |

methyl | 336,000 |

| 4 | benzyl | 1,090,000 | |

| 5 |  |

methyl | 419,000 |

| 6 | benzyl | 1,060,000 | |

| 7a |  |

methyl | 357,100 |

| 8a | benzyl | 63,800 | |

| 9a |  |

methyl | 296,300 |

| 10a | benzyl | 3,200 | |

| 11b |  |

methyl | 201,000 |

| 12b | benzyl | 1,580 | |

| 13b |  |

methyl | 501,000 |

| 14b | benzyl | 1,770 | |

| 15b |  |

methyl | 540,000 |

| 16b | benzyl | 31,000 | |

| 17 |  |

methyl | 981,000 |

| 18 | benzyl | 1,330 | |

Kuang et al. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8(5), 1005–1016.

Compounds were screened as diastereomeric mixtures.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Results and Discussion

We have previously shown that carboxylate derivatives represented by general structure (I) are some of the most potent inhibitors of HNE with kinact/KI values close to 5 × 106 M−1 s−1 and apparent KI values in the sub-nanomolar range.16a,19 We have furthermore established that inhibitory potency is dependent on the pKa of the leaving group (R3COO−), as well as its inherent structure. Thus, the structure of the leaving group can be modulated to probe the S’ subsites of closely-related serine proteases, such as HNE and Pr 3, potentially leading to enhanced binding affinity and enzyme selectivity.20

HNE and Pr 3 are similar in many respects (for instance, the two enzymes have an extended binding site and show a strong preference for small hydrophobic P1 residues), however, they exhibit significant differences in their S’ subsites. S’-P’ interactions play a more important role in catalysis in the case of Pr 3 than HNE.18,22 The S’ subsites of HNE are generally hydrophobic while those of Pr 3 are relatively polar.23 Specifically, the enzymes differ in their S1’-S3’ (as well as the S2 subsite), due to the replacement of Ala 213 and Leu 99 in HNE by Asp 213 and Lys 99 respectively, in Pr 3. Furthermore, the substitution of Leu 143 in HNE to Arg 143 in Pr 3, and the presence of Asp 61 make the S’ subsites of Pr 3 more polar and distinctly different from the hydrophobic HNE subsites. Based on these considerations, we initially set out to probe the S’ subsites of HNE by using a series of structurally-diverse carboxylic acids (R3COOH) and subsequently extend these studies to Pr 3. Our long term objective is to obtain highly selective inhibitors of HNE and Pr 3 which can be used as probes to delineate the precise role(s) each protease plays in the pathophysiology of COPD.

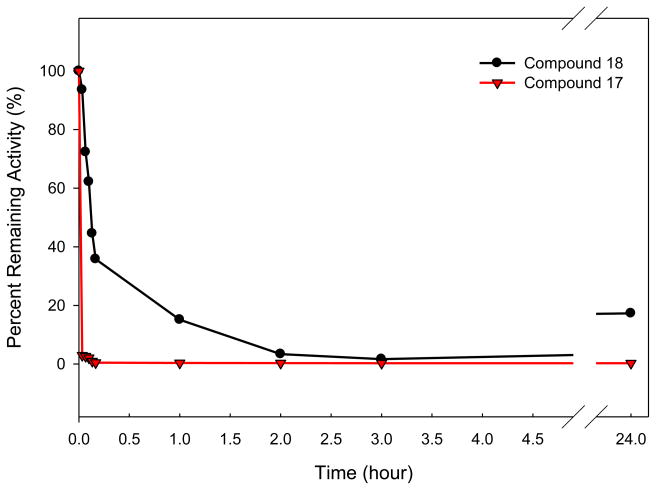

Incubation of compound 17 (or 18) with HNE led to rapid and time-dependent irreversible inactivation of the enzyme (Figure 3). In both cases, the inactivated enzyme regained its activity very slowly, indicating the formation of fairly stable enzyme-inhibitor adducts. This is particularly true in the case of compound 17, an observation that is consistent with previous findings19 The potency of the synthesized inhibitors was determined by generating a series of progress curves (Figure 2) and determining the kinact/KI values by analyzing the data (progress curve method), as described in the experimental section.

Figure 3.

Time dependent loss of enzymatic activity. Percent remaining activity versus time plot obtained by incubating inhibitor 17 or 18 (7 μM) with human neutrophil elastase (700 nM) in 0.1 M HEPES buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.25, and 1% DMSO. Aliquots were withdrawn at different time intervals and assayed for enzymatic activity using MeOSuc-AAPV p-NA by monitoring the absorbance at 410 nm.

The following inferences can be made by careful perusal of the results shown in Table 1: (a) several of the compounds represented by general structure (I) inhibit HNE potently; (b) compounds 3-18 were devoid of any inhibitory activity toward human neutrophil proteinase 3, suggesting that the S’ subsites of HNE are hydrophobic and more tolerant of size, as opposed to the more polar S’ subsites of Pr 3.18,22–23 (c) a range of structurally-diverse hydrophobic elements (R3) can be accommodated at the S’ subsites of HNE. This is in accord with the structure of HNE and the results of previous studies.19–20,24 (d) a noteworthy increase in potency is observed upon replacement of the methyl group at R2 with a benzyl group (compounds 3-6). These observations are consistent with previous studies which have shown that the nature of R2 influences potency, as well as the stability of the enzyme-inhibitor complex,16c,19–20 namely, compounds with small R2 groups (such as methyl) are less potent than the corresponding compounds with larger R2 groups (such as benzyl) and also form acyl enzyme complexes that deacylate very slowly (Figure 2); (e) an unexpected and significant decrease in potency is observed when R2 = benzyl and a spacer of 1–2 carbons connects the carboxylate and aromatic moieties (Table 1, compounds 8,10, 12, 14, 16 and 18). A similar drop in potency was observed in a series of simpler congeners of (I), represented by R3(CH2)nCOOH, with n = 1–2, and R2 = benzyl (exemplified by compounds 8 and 10, Table 1) but not when n = 0 or n = 3–4. Though speculative, these results suggest that the decrease in the inhibitory activity of compounds 8,10, 12, 14, 16 and 18 (Table 1) may be the result of an unproductive hydrophobic collapse,25 namely, the clustering of the hydrophobic groups in the inhibitor molecule in aqueous solution to minimize exposed hydrophobic surface area. All these molecules share a common feature associated with the flexibility and hydrophobicity of their leaving groups. Specifically, the presence of one (or two) sp3-hybridized carbon atoms between the carboxylate group and the aromatic moiety in the leaving group appears to play a critical role in the hydrophobic collapse which forms part of the flexible turn structure of the aromatic moiety, allowing it to fold back and interact hydrophobically with the isobutyl and benzyl groups. The driving force for this phenomenon is thought to be the exclusion of water by such hydrophobic collapse in an aqueous environment.25 Such conformation-directing hydrophobic effects result in an unproductive conformation and have been previously observed as well as exploited in the design of potent ligands.25,26

In conclusion, exploitation of structural differences in the S’ subsites of HNE and Pr 3 has led to the identification of highly selective and potent mechanism-based inhibitors of HNE. Inhibitory activity toward HNE in this series of compounds is influenced by multiple factors, including the possible formation of solvent-induced unproductive conformations.

Experimental

General

The 1H spectra were recorded on a Varian XL-300 or XL-400 NMR spectrometer. A Hewlett-Packard diode array UV/Vis spectrophotometer was used in the in vitro evaluation of the inhibitors. Human neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and Boc-Ala-Ala-Nva thiobenzyl ester were purchased from Elastin Products Company, Owensville, MO. Methoxysuccinyl Ala-Ala-Pro-Val p-nitroanilide and 5, 5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO. Melting points were determined on a Mel-Temp apparatus and are uncorrected. Reagents and solvents were purchased from various chemical suppliers (Aldrich, Acros Organics, TCI America, and Bachem). Silica gel (230–450 mesh) used for flash chromatography was purchased from Sorbent Technologies (Atlanta, GA). Thin layer chromatography was performed using Analtech silica gel plates. The TLC plates were visualized using iodine and/or UV light.

Synthesis of Compounds 3-18

General procedure

To a solution of 2-chloromethyl compound 2 (2 mmol) in 6 mL dry acetone was added sodium iodide (2.2 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The by-product, sodium chloride, was removed by filtration through a small amount of silica gel in a disposable glass pipette. The solvent was then removed and the iodomethyl intermediate re-dissolved in 4 mL dry methylene chloride. To this solution was added a solution of the appropriate carboxylic acid (2.2 mmol) and DBU (2.2 mmol) in 4 mL additional methylene chloride, and the resulting mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The solvent was removed; the residue dissolved in methylene chloride (40 mL) and washed successively with 5% HCl (20 mL), saturated NaHCO3 (20 mL), and finally with saturated sodium chloride (20 mL). The organic layer was then dried over sodium sulfate. The drying agent and solvent were removed, leaving a crude product which was purified by flash chromatography (hexane/methylene chloride or hexane/ethyl acetate) to give compounds 3-18.

Compound 3

oil (84% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.98 (dd, J = 9.5, 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.82–1.98 (m, 3H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 3.92 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 5.90 (q, J = 14.3, 10.0 Hz 2H), 6.84–7.86 (m, 4H), 10.28 (s, 1H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C15H20N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 379.0940, found 379.0953.

Compound 4

oil (63% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.75 (dd, J = 31.5, 6.1 Hz, 6H), 1.62–1.80 (m, 3H), 3.98 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (q, J = 60.5, 14.5 Hz, 2H), 5.91 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 2H), 6.88–7.88 (m, 9H), 10.30 (s, 1H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C21H24N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 455.1253, found 455.1252.

Compound 5

oil (70% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.99 (dd, J = 9.6, 6.3 Hz, 6H), 1.80–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.86–2.00 (m, 1H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 2.90 (s, 3H), 3.90 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 5.84 (dd, J = 18.6, 11.4 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C17H26N3O7S [M+NH4]+ 416.1491, found 416.1500; C17H22N2O7SNa [M+Na]+ 421.1045, found 421.1048.

Compound 6

oil (79% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.73 (dd, J = 33.2, 6.1 Hz, 6H), 1.55–1.80 (m, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 3.92 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.25–4.55 (dd, J = 75.6, 15.6 Hz, 2H), 5.83 (q, J = 21.0, 16.0 Hz, 2H), 7.10–8.06 (m, 9H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H30N3O7S [M+NH4]+ 492.1804, found 492.1821; C23H26N2O7SNa [M+Na]+ 497.1358, found 497.1360.

Compound 11

oil (66% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.88 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H), 0.92–0.98 (dd, J = 11.6, 6.5 Hz 6H), 1.50 (d, J = 6.4 Hz 3H), 1.72–1.92 (m, 4H), 2.45 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.85 (s, 3H), 3.74 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.52–5.72 (m, 2H), 7.06–7.22 (dd, J = 31.9, 7.2 Hz, 4H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C21H36N3O5S [M+NH4]+ 442.2376, found 442.2377; C21H32N2O5SNa [M+Na]+ 447.1930, found 447.1935.

Compound 12

oil (95% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.63–0.78 (dd, J = 38.6, 5.7 Hz, 6H), 0.88 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H), 1.51 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.51–1.89 (m, 4H), 2.42 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 4.20–4.50 (dd, J = 84.9, 13.7 Hz, 2H), 5.62 (m, 2H), 7.09–7.20 (dd, J = 34.8, 6.4 Hz, 4H), 7.36 (s, 5H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C27H40N3O5S [M+NH4]+ 518.2689, found 518.2670; C27H36N2O5SNa [M+Na]+ 523.2243, found 523.2232.

Compound 13

oil (33% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.91–0.98 (dd, J = 17.8, 6.6 Hz, 6H), 1.49–1.51 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.74–1.92 (m, 3H), 2.85 (s, 3H), 3.74 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.77–3.83 (m, 1H), 5.55–5.70 (m, 2H), 6.84–7.38 (m, 9H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H32N3O6S [M+NH4]+ 478.2012, found 478.1999; C23H28N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 483.1566, found 483.1559.

Compound 14

oil (59% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.63 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 0.76 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.51 (d, J = 7.14 Hz, 3H), 1.50–1.72 (m, 3H), 3.74 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 5.62–5.65 (m, 2H), 6.98–7.35 (m, 14H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C29H36N3O6S [M+NH4]+ 554.2325, found 554.2349; C29H32N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 559.1879, found 559.1899.

Compound 15

oil (68% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.88–0.98 (dd, J = 11.6, 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.54 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.72–1.94 (m, 3H), 2.86 (s, 3H), 3.80–3.89 (m, 2H), 5.58–5.71 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.84 (m, 9H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C24H32N3O6S [M+NH4]+ 490.2012, found 490.2051; C24H28N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 495.1566, found 495.1548.

Compound 16

oil (82% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.63–0.76 (dd, J = 35.2, 6.2 Hz, 6H), 1.57 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.45–1.80 (m, 3H), 3.82–3.88 (m, 2H), 4.16–4.52 (dd, J = 84.2, 13.8 Hz, 2H), 5.65 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.35–7.82 (m, 14H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C30H36N3O6S [M+NH4]+ 566.2325, found 566.2330; C30H32N2O6SNa [M+Na]+ 571.1879, found 571.1879.

Compound 17

oil (60% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.93–0.99 (dd, J = 9.8, 6.5 Hz, 6H), 1.76–1.94 (m, 3H), 2.87 (s, 3H), 3.82–3.87 (m, 3H), 5.70 (dd, J = 14.5, 9.7 Hz, 2H), 6.58 (m, 1H), 6.94–7.35 (m, 7H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C22H25Cl2N3O5SNa [M+Na]+ 536.0790, found 536.0781.

Compound 18

oil (67% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3) 0.66–0.79 (dd, J = 36.3, 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.52–1.76 (m, 3H), 3.88 (m, 3H), 4.35 (dd, J = 79.9, 12.3 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (s, 2H), 6.52–7.39 (m, 13H). HRMS (ESI) calculated for C28H30Cl2N3O5S [M+NH4]+ 590.1283, found 590.1279; C28H29Cl2N3O5SNa [M+Na]+ 612.1103, found 612.1108.

Human neutrophil elastase

HNE was assayed by mixing 10 μL of a 70 μM enzyme solution in 0.05 M sodium acetate/0.5 M NaCl buffer, pH 5.5, 10 μL dimethyl sulfoxide and 980 μL of 0.1 M HEPES buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.25, in a thermostated cuvette. A 100 μL aliquot was transferred to a thermostated cuvette containing 880 μL 0.1 M HEPES/0.5 M NaCl buffer, pH 7.25, and 20 μL of a 70 μM solution of MeOSuc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val p-nitroanilide, and the change in absorbance was monitored at 410 nm for 60 seconds. In a typical inhibition run, 10 μL of inhibitor (3.5 mM) in dimethyl sulfoxide was mixed with 10 μL of 70 μM enzyme solution and 980 μL 0.1 M HEPES/0.5 M NaCl buffer, pH 7.25, and placed in a constant temperature bath. Aliquots (100 μL) were withdrawn at different time intervals and transferred to a cuvette containing 20 μL of MeOSuc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val p-nitroanilide (7 mM) and 880 μL 0.1 M HEPES/0.5 M NaCl buffer. The absorbance was monitored at 410 nm for 60 seconds.

Human neutrophil proteinase 3

Twenty microliters of 32.0 mM 5, 5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in dimethyl sulfoxide and 10 μL of a 3.45 μM solution of human proteinase 3 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.50 (final enzyme concentration: 34.5 nM) were added to a cuvette containing a solution of 940 μL 0.1 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.25, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 10 μL 862.5 μM inhibitor in dimethyl sulfoxide (final inhibitor concentration: 8.62 μM) and 20 μL 12.98 mM Boc-Ala-Ala-NVa-SBzl and the change in absorbance was monitored at 410 nM for 2 minutes. A control (hydrolysis run) was also run under the same conditions by adding 5, 5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in dimethyl sulfoxide and 10 μL of a 3.45 μM solution of human proteinase 3 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.50 (final enzyme concentration: 34.5 nM) to a cuvette containing a solution of 940 μL 0.1 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.25, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 10 μL dimethyl sulfoxide and 20 μL 12.98 mM Boc-Ala-Ala-NVa-SBzl and the change in absorbance was monitored at 410 nM for 2 minutes. Pr 3 activity remaining was determined using % remaining activity = (v/vo) × 100 and is the average of duplicate or triplicate determinations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL 57788).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Abboud RT, Vimalanathan S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;12:361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Zheng S. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1238–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Griese M, Kappler M, Gaggar A, Hartl D. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:783–795. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Wang Z, Chen F, Zhai R, Zhang L, Su L, Lin X, Thomson T, Christiani DC. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hashimoto S, Okayama Y, Shime N, Kimura A, Funakoshi Y, Kawabata K, Ishizaka A, Amaya F. Respirology. 2008;13:581–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida Y, Freitas MC, Zhao D, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Transplantation. 2010;89:1050–1056. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d45a98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houghton AM, Rzymkiewicz DM, Ji H, Gregory AD, Egea EE, Metz HE, Stolz DB, Land SR, Marconcini LA, Kilment CR, Jenkins KM, Beaulieu KA, Mouded M, Frank SJ, Wong KK, Shapiro SD. Nat Med. 2010;16:219–223. doi: 10.1038/nm.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen PA, Sallenave JM. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1095–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacNee W. Proc Am Thor Soc. 2005;2:50–60. doi: 10.1513/pats.200411-056SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luppi F, Hiemstra PS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:527–531. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1821ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Aoshiba K, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:555–562. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0090OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tuder RM, Petrache I, Elias JA, Voelkel NF, Henson PM. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:551–554. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demedts IK, Demoor T, Bracke KR, Joos GF, Brusselle GG. Respir Res. 2006;7:53–62. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro SD, Ingenito EP. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:367–372. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rennard SI. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;160:S12–S16. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Croxton TL, Weinmann GG, Senior RM, Wise RA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1142–1149. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-756WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stockley RA, Mannino D, Barnes PJ. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:524–526. doi: 10.1513/pats.200904-016DS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:394–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Chua F, Laurent GJ. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:424–427. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-078AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moraes TJ, Chow CW, Downey GP. Crit Care Med. 2003:S189–S194. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057842.90746.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Malhotra S, Man SFP, Sin DD. Exp Opin Emerging Drugs. 2006;11:275–291. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barnes PJ. Chest. 2008;134:1278–1114. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Huang W, Yamamoto Y, Li Y, Dou D, Alliston KR, Hanzlik RP, Williams TD, Groutas WC. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2003–2008. doi: 10.1021/jm700966p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Groutas WC, Epp JB, Ruan S, Yu S, Huang H, He S, Tu J, Schechter NM, Turbov J, Froelisch CJ, Groutas WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8128–8129. [Google Scholar]; (c) Groutas WC, Kuang R, Venkataraman R, Epp JB, Ruan S, Prakash O. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4739–4750. doi: 10.1021/bi9628937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomenclature used is that of Schechter I, Berger A. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x., where S1, S2, S3,…Sn and S1′, S2′, S3′,…Sn’ correspond to the enzyme subsites on either side of the scissile bond. Each subsite accommodates a corresponding amino acid residue side chain designated P1, P2, P3, ….Pn and P1′, P2′, P3′, ….Pn’ of the substrate or (inhibitor). S1 is the primary substrate specificity subsite, and P1-P1′ is the scissile bond.

- 18.(a) Hajjar E, Broemstrup T, Kantari C, Witko-Sarsat V, Reuter V. FEBS J. 2010;277:2238–2254. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Korkmaz B, Moreau T, Gauthier F. Biochimie. 2008;90:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuang R, Epp JB, Ruan S, Chong LS, Venkataraman R, Tu J, He S, Truong TM, Groutas WC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2000;8:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Dou D, He G, Lushington GH, Groutas WC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:3536–3542. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Morrison JF, Walsh CT. Adv Enzymol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wakselman M, Xie J, Mazaleyrat JP. J Med Chem. 1993;36:1539–1547. doi: 10.1021/jm00063a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korkmaz B, Knight G, Bieth J. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12609–12612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujinaga M, Chenaia MM, Halenbeck R, Koths K, James MNGJ. Mol Biol. 1996;261:267–278. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Groutas WC, Epp JB, Kuang R, Ruan S, Chong LS, Venkataraman R, Tu J, He S, Yu H, Fu Q, Li YH, Truong TM, Vu NT. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;385:162–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wei L, Lai Z, Gan X, Alliston KR, Lai Z, Epp JB, Tu J, Perera AB, Van Stipdonk M, Groutas WC. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;429:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Groutas WC, He S, Kuang R, Ruan S, Tu J, Chan HK. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:1543–11548. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiley RA, Rich DH. Med Res Revs. 1993;13:327–384. doi: 10.1002/med.2610130305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcomb LF, Haque TS, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6509–6519. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Desai MC, Vincent LA, Rizzi JP. J Med Chem. 1994;37:4263–4266. doi: 10.1021/jm00051a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vander Velde DG, Georg GI, Grunewald GL, Gunn CW, Mitscher LA. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11650–11651. [Google Scholar]