Abstract

Selective attention enables sensory input from behaviorally relevant stimuli to be processed in greater detail, so that these stimuli can more accurately influence thoughts, actions, and future goals. Attention has been shown to modulate the spiking activity of single feature-selective neurons that encode basic stimulus properties (color, orientation, etc.). However, the combined output from many such neurons is required to form stable representations of relevant objects and little empirical work has formally investigated the relationship between attentional modulations on population responses and improvements in encoding precision. Here, we used functional MRI and voxel-based feature tuning functions to show that spatial attention induces a multiplicative scaling in orientation-selective population response profiles in early visual cortex. In turn, this multiplicative scaling correlates with an improvement in encoding precision, as evidenced by a concurrent increase in the mutual information between population responses and the orientation of attended stimuli. These data therefore demonstrate how multiplicative scaling of neural responses provides at least one mechanism by which spatial attention may improve the encoding precision of population codes. Increased encoding precision in early visual areas may then enhance the speed and accuracy of perceptual decisions computed by higher-order neural mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

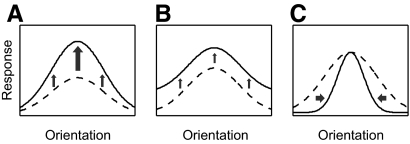

In many situations an observer must selectively enhance the perceived visual detail in a behaviorally relevant portion of the periphery at the expense of detail in other peripheral locations. The perceptual benefits obtained by covertly monitoring relevant parafoveal objects depend on modulating the neural responses that encode basic visual features such as edge contours and colors, a phenomenon referred to as selective attention (Connor et al. 1997; Desimone and Duncan 1995; Moran and Desimone 1985). The spatial component of selective attention (spatial attention) increases neural activity in retinotopically corresponding cortical regions for all features in that spatial location, much like a spotlight illuminating only a part of a theater stage (Boynton 2005; Koch and Ullman 1985; Posner et al. 1980; Tsotsos et al. 1995). But how exactly is the encoding of relevant features influenced by spatial attention and how might it enhance perception? Single-unit recording data collected in nonhuman primates suggest that spatial attention primarily acts to multiply feature tuning functions by a constant factor (referred to here as multiplicative scaling; see McAdams and Maunsell 1999; Treue and Martinez-Trujillo 1999; Fig. 1A). In addition to multiplicative scaling, spatial attention is also thought to induce a feature-nonspecific increase in response amplitudes, which can occur even in the absence of a stimulus (referred to here as additive scaling, also known as a baseline shift; Kastner et al. 1999; Luck et al. 1997; see Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of the possible types of attention-induced scaling in the neuronal tuning function and, consequently, in population response profiles. A: multiplicative scaling or feature-dependent increase in response amplitude, where the increase depends on the proximity of the attended stimulus feature to the preferred feature of the neuron. B: additive scaling or feature-nonspecific increase in response amplitudes. C: bandwidth scaling or change in SD of response profile.

Functionally, spatial attention is thought to improve the quality of perceptual representations in part by selectively increasing the firing rates of neurons tuned to the attended stimulus (assuming approximately Poisson neurophysiological noise; Martinez-Trujillo and Treue 2004; McAdams and Maunsell 1999; Shadlen and Newsome 1994; Treue and Martinez-Trujillo 1999). Even though single-unit recording studies have demonstrated such attentional modulations, coherent perceptual representations are thought to be based on populations of sensory neurons working in concert (Averbeck et al. 2006; Butts and Goldman 2006; Jazayeri and Movshon 2006; Kang et al. 2004; Pouget et al. 2003). Therefore, the goal of the present study was to explicitly examine the theoretical and empirical link between spatial attention and the encoding precision of population responses in early areas of human visual cortex.

We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to define feature-selective voxel tuning functions and then used information theoretic measures (Nevado et al. 2004; Panzeri et al. 2008) to infer changes in the encoding precision of population responses due to spatial attention. We find that spatial attention increases the amount of information encoded in early visual cortices about the features of an attended stimulus, primarily by modulating the multiplicative scaling of population response profiles. Since the quality of a population code can be assessed using information theory (Doya 2007; Mackay 2003), the observed multiplicative scaling provides a mechanism by which spatial attention improves encoding precision of population codes. In turn, the improved quality of stimulus representations in early visual areas should facilitate the read-out of information by higher brain areas during perceptual decision making (Ditterich et al. 2003; Jazayeri and Movshon 2006; Newsome et al. 1989; Shadlen and Newsome 2001).

METHODS

Subjects

Eight neurologically healthy subjects between the age of 18 and 30 yr were recruited from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) community to participate in the experiment. Data from one subject were subsequently discarded because of an inability to obtain robust retinotopic maps. Each subject gave written informed consent, in accordance with Institutional Review Board requirements at UCI, and completed 1 h of training outside the scanner before completing two 1.5 h scanning sessions held on separate days. Thus the data presented here represent a total of 14 scanning sessions.

Selective attention scans

Subjects were instructed to maintain fixation on a central fixation point (white in color, subtending 0.5° of visual angle) that persisted on the screen for the duration of each scan (where a “scan” refers to a single fMRI data collection run lasting 410 s). Each scan consisted of several trials; on each 10 s trial, a full-contrast grayscale sinusoidal annular grating (0.5 cycle/deg) was flickered at 2 Hz (250 ms on, 250 ms off) in one of eight possible orientations (0, 22.5, 45, 67.5, 90, 112.5, 135, and 157.5°, where 0° is horizontal; see Fig. 2A), which defined a single stimulus. The spatial phase of the stimulus grating was randomly shifted every 250 ms within each trial to attenuate adaptation and apparent motion. The entire stimulus (left to right) subtended 22.5° of visual angle with a central circular aperture (11.2° diameter) removed around fixation; the annulus was disconnected at top and bottom so that each semicircular stimulus grating occupied only one visual hemifield (each stimulus “wedge” occupied 40% of the full annulus). The order of stimulus orientations was randomized on each scan, with the constraint that the same orientation could not be presented on successive trials. Stimulus gratings in both hemifields had the same orientation to ensure that any effects of global-feature-based attention remained constant throughout the task (Saenz et al. 2002; Serences and Boynton 2007; Treue and Martinez-Trujillo 1999). Subjects attended to the stimulus grating presented in either the left or the right hemifield in response to a horizontal cue extending 1° of visual angle from the central fixation point (Fig. 2B). This cue remained on the screen for the duration of each trial. Subjects were instructed to respond when the contrast of the stimulus grating in the attended hemifield decreased slightly, which is henceforth referred to as a target event (subjects were to ignore equally frequent contrast changes that occurred in the unattended hemifield, which was done to equate sensory factors between the attended and unattended stimuli). The contrast reduction that defined a target was titrated on an individual basis so that the hit rate remained at roughly 75–80% over the course of all scanning sessions (a “hit” was defined as a response that occurred ≤1 s after the presentation of a target; subjects false-alarmed infrequently on only 1.9 ± 0.7% SE of contrast changes in the distractor stimulus). Each target was presented for a single 250 ms frame and there were four targets in each trial. The timing of each target was pseudorandomly determined with the following constraints: each target was separated from the previous one by ≥1.5 s and targets were restricted to a temporal window of 1–9 s following the onset of the trial. Each trial was separated from the next by a blank 500 ms intertrial interval of passive fixation. Observers completed five or six attention scans per 1.5 h scanning session; each scan lasted 410 s and contained four presentations of each stimulus orientation (32 in total) along with six pseudorandomly interleaved “null” trials in which only the central fixation point was visible for the entire 10 s trial interval. These null trials were presented to provide a common baseline for comparison of responses evoked by attended and unattended stimuli.

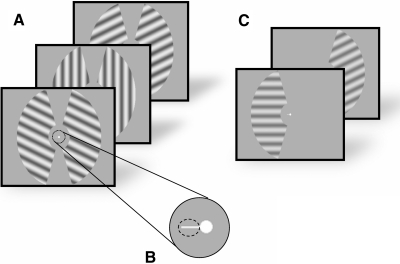

Fig. 2.

A: schematic of the task performed by subjects during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning. Subjects attended to a flickering (2 Hz) sinusoidal grating that was rendered in one of 8 possible orientations [0, 22.5, 45, … , 157.5°]. Subjects were required to continuously fixate on the spot at the center of the display and to attend to either the left or the right stimulus based on a small central cue (B). Subjects pressed a button whenever they detected a slight dimming of the attended stimulus and ignored an equally probable dimming of the unattended stimulus. Target contrast decrements were titrated to maintain detection accuracy at about 75–80%. Stimuli in both hemifields were rendered in the same orientation to negate the influence of global feature-based attentional modulations (see methods). C: independent localizer scans were used to identify the most spatially selective voxels in V1–hV4. The stimulus was similar to that used in the attention task (above) except that it was visible in only one hemifield, to which the subject had to direct his/her attention.

Independent functional localizer scans

Two independent functional localizer scans were run during each scanning session to identify voxels within each retinotopically organized visual area that responded to the spatial position occupied by the stimuli in the left and right hemifields during the attention scans. The stimuli used during localizer scans were identical to the stimuli used during attention scans; however, only one hemifield was stimulated on each trial (Fig. 2C). Subjects were asked to fixate on the central fixation point and direct their attention to the presented stimulus. There was a blank intertrial interval of 10 s following each stimulus presentation and each of the eight orientations was presented twice during each localizer scan (total scan duration: 320 s).

Retinotopic mapping procedures

Retinotopic mapping data were obtained in one to two scans per subject, using a checkerboard stimulus and standard presentation parameters (stimulus flickering at 8 Hz and subtending 60° of polar angle; Engel et al. 1994; Sereno et al. 1995). This procedure was used to identify ventral visual areas V1, V2v, V3v, and hV4. Our high-resolution scanning protocol did not provide sufficient coverage to acquire data from dorsal occipital areas V2d, V3d, and V3a or visual areas in parietal and frontal cortex. To aid in the visualization of early visual cortical areas, we projected the retinotopic mapping data onto a computationally inflated representation of each subject's gray–white matter boundary.

fMRI data acquisition and analysis

MRI scanning was carried out on a Philips Achieva 3-Tesla scanner equipped with an 8-channel SENSE (sensitivity-encoded) head coil at the John Tu and Thomas Yuen Center for Functional Onco-Imaging, University of California, Irvine. Anatomical images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo T1-weighted sequence that yielded images with a 1 mm3 resolution (repetition time/time to echo [TR/TE] = 11/3.3 ms, inversion time [TI] = 1,100 ms, 150 slices, flip angle = 18°, with no SENSE acceleration). Functional images were acquired using a gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) pulse sequence, which covered the occipital lobe with 25 oblique transverse slices. Slices were acquired in sequential order with 1.5 mm thickness and 0.5 mm gap to avoid slice cross talk; thus a 50 mm thick slab was acquired (TR = 2,500 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 70°, image matrix = 120 anterior–posterior [AP] × 92 right–left [RL], with field of view = 240 mm AP × 180 mm RL, SENSE factor = 2, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 1.5 mm).

Data analysis was performed using BrainVoyager QX (v 1.86; Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and custom time-series analysis routines written in Matlab (v 7.1; The MathWorks, Natick, MA). All EPI images were slice-time corrected, motion-corrected (both within and between scans), and high-pass filtered (3 cycles/run) to remove low-frequency temporal components from the time series.

Region of interest selection procedure

To identify voxels that responded to the retinotopic position of the stimulus aperture, data from the functional localizer scans were analyzed using a general linear model (GLM) that contained two regressors marking each 10 s epoch of stimulation in the left and right hemifields (a boxcar convolved with a standard double-gamma function as implemented in Brain Voyager: time to peak, 5 s; undershoot ratio, 6; time to undershoot peak, 15 s; Boynton et al. 1996). Voxels within each visual area that responded more to one epoch of stimulation compared with the other were retained for further analysis if they passed a threshold of P < 0.01, corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) algorithm implemented in BrainVoyager QX (see Genovese et al. 2002). See Table 1 for the number of voxels within each visual area that passed this threshold.

Table 1.

Average size across subjects for each visual area

| Visual Area | Mean Voxels | SD |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | 551.43 | 163.68 |

| V2v | 251.79 | 105.12 |

| V3v | 233.29 | 81.93 |

| hV4 | 237.57 | 113.25 |

Voxel tuning functions

We used voxel tuning functions (VTFs) to evaluate feature-selective blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) responses in early areas of visual cortex. The feature selectivity is thought to be indirectly determined by biases in the distribution of orientation-selective neurons (e.g., columns in V1) that are idiosyncratically sampled within each voxel (Haynes and Rees 2005; Kamitani and Tong 2005; Kay et al. 2008; Sasaki et al. 2006; Serences et al. 2009; Swisher et al. 2010). In turn, if a voxel has a bias in the number of neurons that prefer a particular feature, then that voxel should exhibit a weak but detectable feature-selective response bias.

Estimating orientation-specific responses

First, the time series from each voxel was normalized by subtracting the mean activation level for that voxel on a scan-by-scan basis. Next, the magnitude of the BOLD response in each voxel was estimated using a GLM that contained regressors for attended and unattended stimuli rendered in each of the eight possible orientations (boxcar model of stimulus sequence convolved with standard difference-of-two gamma functions). For example, on a trial where the subject was attending to the stimulus in the left hemifield, an “attended” response would be measured from all voxels in the contralateral right hemisphere and an “unattended” response would be measured in the ipsilateral left hemisphere.

Assigning orientation preference to each voxel

The orientation preference of each voxel was assigned using a leave-one-out procedure to ensure that the resulting tuning functions reflect reliable changes in signal as opposed to idiosyncratic noise. First, each voxel from a visual area was assigned to one of eight orientation-preference bins based on data from all scans except one; orientation preference was heuristically established by determining the orientation that evoked the largest response after removing the mean response across all voxels in response to each orientation (see Supplemental Fig. S7 for an alternate heuristic).1 This mean subtraction was performed to correct for main effects of stimulus orientation that had a common influence on the response of every voxel, thereby emphasizing the differential pattern of responses across voxels (see e.g., Haxby et al. 2001). Supplemental Fig. S11 shows not only the mean response amplitude to each orientation in each visual area, but also the distribution of orientation preferences with and without this correction. Supplemental Fig. S8 shows the fully analyzed data without removing the main effect of orientation: qualitatively similar results are observed.

After determining the orientation preference of each voxel, we used data from the held-out scan to compute the response of voxels in each bin to both attended and unattended stimuli rendered in all eight possible orientations (thus producing a VTF). This hold-one-out procedure was then repeated using all unique permutations of holding one scan out and the final VTF for a given visual area in a given subject reflects the average across all permutations. Finally, VTFs from each visual area were averaged across left and right hemispheres because no systematic asymmetries were observed.

Characterizing VTFs using a circular Gaussian

Voxel tuning functions were mathematically characterized as

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

where f is a circular Gaussian function (Dayan and Abbott 2001; Nevado et al.,2004; Pouget et al. 2003), α is the additive scaling parameter, β is the multiplicative scaling parameter, and κ is the concentration parameter or bandwidth. Once the distribution for B(Θ) had been estimated using the above-mentioned procedure, an iterative curve-fitting algorithm was used to derive best-fit values for α, β, and κ. Thus voxel tuning curves were constructed reflecting BOLD activation under attention Ba(Θ) and without attention Bu(Θ) such that

is a circular Gaussian function (Dayan and Abbott 2001; Nevado et al.,2004; Pouget et al. 2003), α is the additive scaling parameter, β is the multiplicative scaling parameter, and κ is the concentration parameter or bandwidth. Once the distribution for B(Θ) had been estimated using the above-mentioned procedure, an iterative curve-fitting algorithm was used to derive best-fit values for α, β, and κ. Thus voxel tuning curves were constructed reflecting BOLD activation under attention Ba(Θ) and without attention Bu(Θ) such that

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

The effect of spatial attention was then characterized as

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

| (3c) |

The model was fit to data from each visual area in each subject using a gradient descent algorithm implemented in the Matlab Optimization Toolbox (built around the “fminsearch” function that uses the Nelder–Mead Simplex Direct Search; Lagarias 1998). Because the starting value assigned to each parameter can influence the final outcome of gradient descent algorithms (in case of many local minima), each fit was performed 60 times with a new seed for each of the three free parameters drawn randomly from a normal distribution in an attempt to find the globally optimal parameter values. The mean of each normal distribution used to generate the seeds was set as follows: 1) the minimum of the data for the additive scaling parameter, 2) the maximum response minus the minimum response for the multiplicative scaling parameter, and 3) 0.5 for the bandwidth parameter. The SD of the seed distribution was set to the square root of the respective mean for that distribution. The iteration with the lowest overall root mean square error (RMSE) across all 60 iterations in a given subject was then used in the final analysis (mean RMSE ± SE: 0.02157 ± 0.002162, indicating that the fits were excellent overall). A validation procedure in which 500 iterations of the analysis were run with randomized labels was also carried out; this resulted in a more than twofold increase in RMSE, further supporting the significance of the observed Gaussian shape of the VTFs (mean RMSE with randomized labels: 0.049).

Since all stimuli had the same luminance contrast, we could not model the tuning function with contrast as a free parameter. Thus we cannot rule out the possibility that the values of α, β, and κ have some dependence on stimulus contrast and thus these parameters could be a function of contrast.

We also investigated the appropriateness of an alternate model B(Θ) = β∗[f(κ, Θ) + α], where the multiplicative scaling parameter also operates on the additive scaling parameter. When reasonable constraints on allowable parameter values are imposed (e.g., nonnegative additive scaling factor), then the model described in Eqs. 2a and 2b proved to be a better fit to the data (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Mutual information measures

In the present study, we use an information-theoretic quantity mutual information (MI) both to rank-order voxels based on the theoretical homogeneity of comprising neural populations and to evaluate the influence of attention on the quality of neural codes (the methods described here follow those described in Serences et al. 2009). MI has the advantage that it indexes the information conveyed by a voxel about the stimulus and makes no a priori assumptions about the precise shape of the response distribution (Fuhrmann Alpert et al. 2007; Panzeri et al. 2008; Serences et al. 2009). MI is based on Shannon's entropy of the BOLD responses in each voxel, which is a measure of response uncertainty across all stimulus orientations

| (4) |

To compute Shannon's entropy, we converted the continuous BOLD response into a discrete variable (B) by dividing the range of responses into a set of equidistant bins (b) of sufficiently small size (Cover and Thomas 1991). In this formulation, p(b) is the frequency with which a response falls into bin b divided by the total number of responses measured from a given voxel. The bins were statically defined (i.e., fixed for all data sets) and spanned the entire range of values encountered in the data. Before discretizing BOLD responses for a given voxel, we collapsed data collected in response to both attended and unattended stimuli after subtracting out the mean activation levels of “attended” and “unattended” conditions. This subtraction was done because additive shifts attributed to attention would have induced error in the process of binning BOLD responses during the computation of p(b). Next, we computed conditional entropy p(b|θ), which yields a measure of response uncertainty, given the knowledge of stimulus orientation (θ). If there is a dependence between stimulus orientation and observed BOLD responses, the introduction of Θ as a conditional random variable should reduce the uncertainty and thus the entropy of the random variable B

| (5) |

The information content carried by each voxel can then be defined as the reduction in uncertainty for each voxel's BOLD response given the stimulus orientation, or mutual information (MI). Since we are using logarithm to the base 2 in our calculations, the unit of measure is bit

| (6) |

Bayes' rule ensures that the equation is symmetric, so that I(B|Θ) is equal to I(Θ|B) or the reduction in uncertainty about stimulus orientation given a distribution of BOLD responses. Therefore if there is a strong dependence of the distribution of BOLD responses (B) and stimulus orientation (Θ) for a particular voxel, then that voxel will yield a high MI value. If they are completely dependent, such that knowing one gives complete information about the other, then MI would be equal to the entropy of either one of them. On the other hand, if the distributions of BOLD responses and stimulus orientation are completely independent, then that voxel will yield an MI value of zero. In the present experiment, where eight different stimulus orientations were used, the maximum possible value of MI is 3 (log2 8).

Normalized MI

For the analysis of modulation in MI with attention (Fig. 9), we used the normalized version of mutual information (Kojadinovic 2005) to normalize the values of voxel MI derived from different subjects to range between 0 and 1

| (7) |

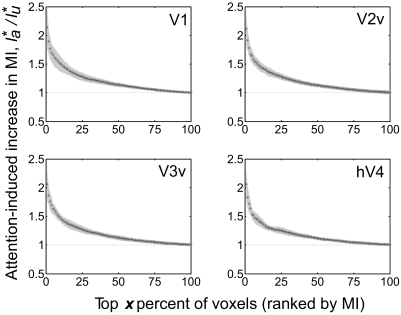

Fig. 9.

Ratio of normalized MI (see methods) for voxels in V1, V2v, V3v, and hV4 between attended and unattended stimuli. Voxels were sorted by normalized MI based on unattended responses only. The abscissa marks different groups of top voxels (by percentage of the total voxels ranked by their MI score). /* refers to normalized MI (see methods) derived from unattended responses and attended responses, respectively. Ordinate refers to their ratio. Shaded gray patch around data points highlights the SD of values between subjects. High-MI voxels showed higher increase in overall information content with attention.

A value of 1 for I* means that knowing B gives complete information about the value of Θ or vice versa. Conversely, a value of 0 implies that knowing B provides no information about Θ or complete independence between the distributions of B and Θ.

Relationship between the shape of a VTF and MI

MI depends on the difference between overall response variability [total entropy or H(B)] and response variability that is attributable to factors uncorrelated with the stimulus [noise entropy or H(B|Θ)]. The difference between total entropy and noise entropy thus represents how much variability in the BOLD responses is attributable to changes in the stimulus, which indicates how much signal, or useful information, is present in the data. For an informative voxel, entropy H(B) should be high, implying that the magnitude of the BOLD response changes substantially as a function of stimulus orientation. Thus a voxel that has a peaked tuning function would be more informative than a voxel that has a flat tuning function, all else being equal (although the relationship between MI and tuning function bandwidth is nonmonotonic, such that flat or overly peaked voxels both have a lower MI than that of voxels with some optimal intermediate bandwidth). Conditional entropy H(B|Θ) for an informative voxel should be relatively low [with respect to the entropy H(B)] because that voxel should yield similar BOLD responses on each successive presentation of the same orientation, implying low noise.

Using MI as a criterion to select representative voxels

We hypothesized that the magnitude of MI in a voxel should be directly proportional to the underlying distribution of feature selectivity at the neural level, making only the assumption that there is a monotonic relationship between neural activity and the magnitude of the BOLD response (Logothetis 2003; Logothetis et al. 2001). Consider two hypothetical and extreme types of voxel: 1) a voxel with very weak orientation selectivity and 2) a voxel with strong selectivity and a robust VTF. In the first case, weak selectivity might be caused either by poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR; e.g., if the voxel partially samples white matter) or by a relatively heterogeneous distribution of orientation-selective neurons within the voxel, which would result in a null orientation preference because the voxel would respond equally well to all orientations. In turn, this nonselective response profile would have low entropy and correspondingly low MI. Therefore we argue that voxels with weak VTFs (characterized by low MI) are difficult to interpret because multiple factors may contribute to poor orientation tuning and, consequently, denature the observable effects of attention. The opposite is true in a relatively homogeneous voxel containing many neurons tuned to a specific orientation. Such a voxel should have a highly selective and peaked VTF, high total entropy, and a correspondingly high MI (assuming nearly Poisson or additive noise). Therefore voxels with high MI should contain a relatively homogeneous sample of orientation-selective neurons and thus provide the best insight into the operating characteristics of attention on specific neural populations (for a more formal description of this model, see Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2; also see Nevado et al. 2004).

Based on this logic, voxels were rank-ordered based on their MI score and orientation preference within all scans save one and then the VTFs were generated based on data from the remaining scan (rank-ordering always done separately for each visual area, session, and subject). Different quartiles out of this rank-ordered list were then selectively analyzed because quartiles were large enough intervals to provide an adequate number of voxels in each bin to compute reliable tuning curves (see e.g., Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplemental Fig. S3). Note that the mutual information measure suffers from the problem of bias in estimated values when data are limited (Panzeri et al. 2007). However, since we used MI values only to rank-order voxels derived from the same data set, the exact MI value of each voxel becomes immaterial as long as it gives an accurate representation of the relative information content of that voxel vis-à-vis other voxels in its orientation-preference bin (and visual area, session, and subject).

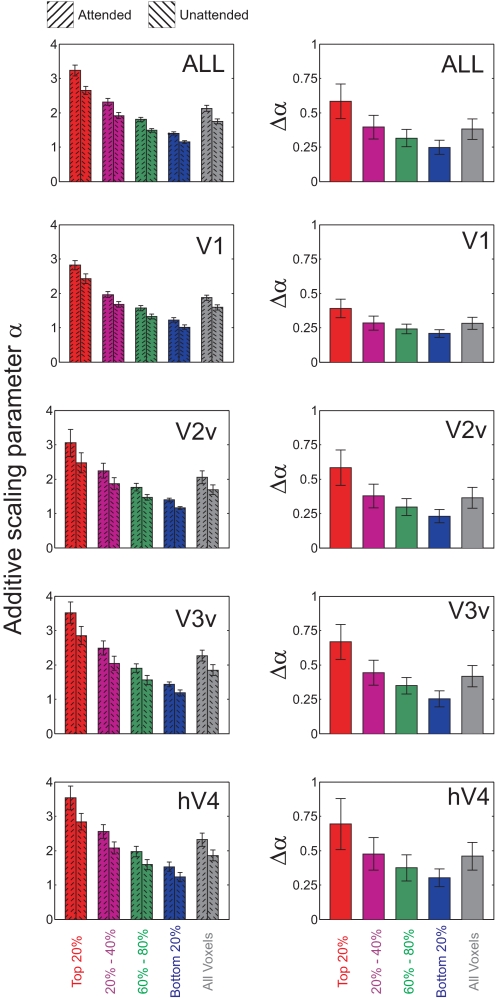

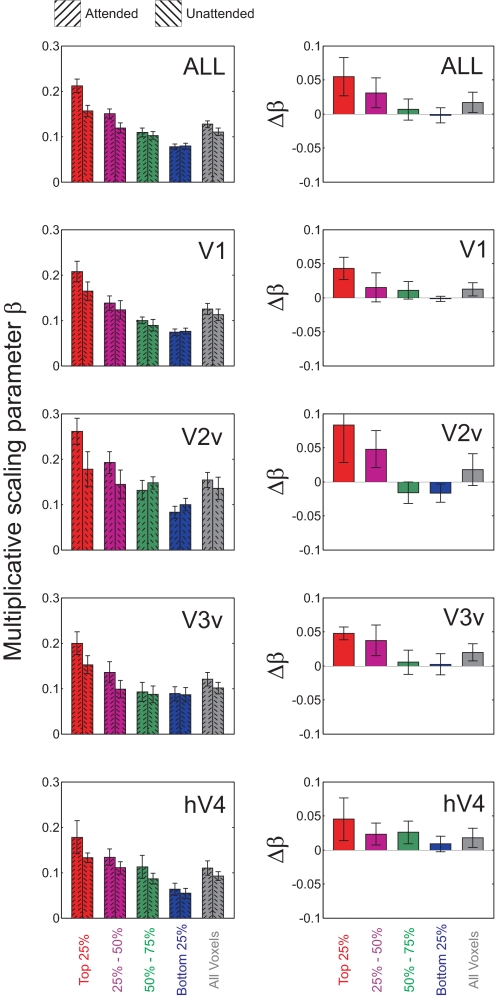

Fig. 6.

Additive scaling with attention for each MI quartile in V1, V2v, V3v, and hV4. Left panels show additive scaling parameter derived separately from attended data and unattended data. Right panels show the net change (attended minus unattended) in the parameter with attention. Top row shows data averaged across all visual areas; remaining rows show data from each visual area. Error bars reflect ±1SE across subjects.

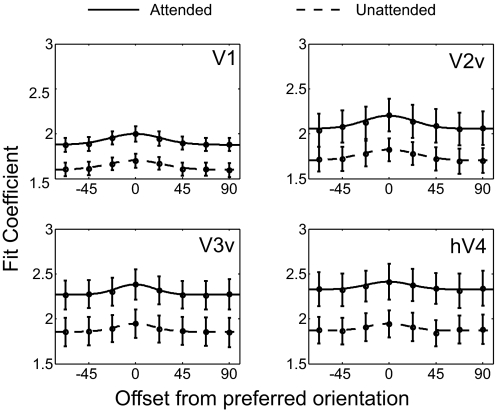

Fig. 7.

Multiplicative scaling with attention for each MI quartile in V1, V2v, V3v, and hV4. Left panels show multiplicative scaling parameter derived separately from attended data and unattended data. Right panels show the net change (attended minus unattended) in the parameter with attention. Top row shows data averaged across all visual areas; remaining rows show data from each visual area. Error bars reflect ±1SE across subjects.

Relationship between attentional gain and MI

Spatial attention can influence a Gaussian tuning function in three ways: additive scaling, multiplicative scaling, and bandwidth scaling. Multiplicative scaling should increase MI since it increases the dynamic range of mean responses, which in turn increases the entropy of responses H(B). Even under the assumption of Poisson noise, multiplicative scaling will cause the entropy of responses to increase faster than the corresponding increase in noise entropy, leading to an overall increase in MI. This also holds for additive Gaussian noise, as long as the variance increases by a factor smaller than the increase in the mean BOLD response. In contrast, additive scaling of a tuning function will not increase entropy because it simply translates the tuning curve up or down without increasing the dynamic range of mean responses. If the noise scales with mean response (e.g., Poisson noise), additive scaling might actually lower MI because the noise entropy will increase much faster than overall entropy. Finally, the relationship between MI and the bandwidth of a tuning function is nonmonotonic. A decrease in bandwidth would increase MI if the bandwidth was nonoptimally wide (e.g., a flat tuning function). However, a decrease in bandwidth beyond an optimal intermediate point would also lower MI because the tuning function would convey information only about a highly restricted range of stimulus values. Thus an increase in bandwidth—to a point—would help if the bandwidth was overly narrow.

Using MI of BOLD responses to evaluate the quality of population codes

If BOLD responses are approximately linearly related to changes in underlying neuronal firing (Heeger et al. 2000; Logothetis 2003; Logothetis et al. 2001), then an increase in a voxel's MI with attention implies an increase in information conveyed by the population of neurons that are contained within that voxel. This relationship holds even if we allow a nonlinear relationship between neural activity and the BOLD response, as long as the relationship remains monotonic (i.e., if an increase in neural spiking activity leads to some increase in BOLD amplitude; Nevado et al. 2004). Under this relaxed assumption of monotonicity, the BOLD response profile can be thought of as a filtered version of the neural population response profile— filtered through some monotonic mapping function—forming a Markov chain. The data inequality theorem (Cover and Thomas 1991) mandates that for such a Markov chain, the MI of a voxel must be equal to or less than the MI of the neural population. Therefore even the most informative voxel can never have higher information in its BOLD responses than that of the MI that exists in the underlying neural population activity, thus providing an upper bound on any estimates of the information content of population responses. As a result, the absolute value of the increase in MI with attention exhibited at the voxel level is not expected to be equal to the actual increase in MI at the neural level; however, the qualitative relationship between changes in MI at the neuronal and voxel levels should be preserved.

Eye tracking

Eye tracking data were acquired with an ASL504 LRO (long-range optics) MRI-compatible system (Applied Science Laboratories, Bedford, MA) that tracked the right pupil of three subjects during scanning (one subject in both sessions and the others in a single session each) at 60 Hz. Data were analyzed off-line using the ILAB analysis toolbox implemented in Matlab (Gitelman 2002). First, the raw data were binned into epochs corresponding to the 10 s stimulus presentation interval from each trial. Blinks (periods when the pupil disappeared), as well as five samples on either side of each blink, were then marked and removed from the epoched data. Saccadic eye movements were then identified when the velocity of the eye exceeded 30°/s for at least two samples; a minimum saccade distance of 1° was also imposed because this is the manufacturer-stated resolution of the eye tracker. Supplemental Fig. S5 shows the mean X, Y position of the saccade endpoints for each of the eight stimulus orientations; no systematic differences as a function of the attended location were observed.

We could acquire eye-tracking data from only three subjects because of various technical impediments that made it difficult to acquire steady measurements from several subjects. In such cases where data could not be acquired consistently, subject fixation was monitored manually by both authors (using the eye-tracker camera) to ensure that subjects did not make systematic saccades with the attentional cues and were fixating consistently on the central fixation spot.

RESULTS

To characterize the impact of spatial attention on population response profiles, we used the spatial attention task shown in Fig. 2. We first generated voxel tuning functions (VTFs) with and without spatial attention within each visual area (Fig. 3; see Voxel tuning functions in methods). One-way repeated measures ANOVAs revealed significant orientation selectivity of the VTFs in all areas [after collapsing across attended and unattended trials: V1: F(7,42) = 18.3, P < 0.001; V2v: F(7,42) = 19.4, P < 0.001; V3v: F(7,42) = 5.9, P < 0.001; hV4: F(7,42) = 3.7, P < 0.005].

Fig. 3.

Voxel tuning functions (VTFs) with attention (solid curve) and without attention (dashed curve) based on responses in V1, V2v, V3v, and hV4. These mean tuning functions were produced by centering all VTFs (for a visual area) at their preferred orientation and then averaging across subjects (lines represent best-fitting circular Gaussian; see methods). Error bars reflect ±1SE across subjects. The y-axis refers to the magnitude of the fit coefficients (beta weights) estimated using the general linear model (GLM; see methods).

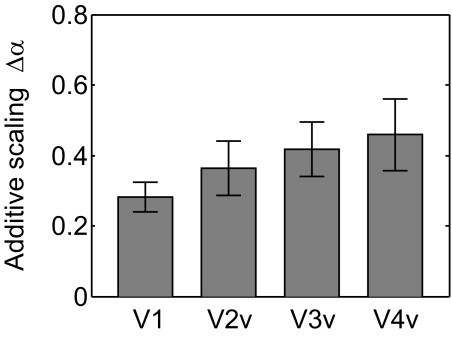

When considering all spatially selective voxels identified using the independent functional localizer scans, we found that spatial attention primarily produced an additive scaling of VTFs that was highly significant in all four visual areas. This magnitude of the additive scaling also increased modestly from V1 to hV4 [F(3,18) = 3.13, P = 0.051, marginally significant one-way repeated measures ANOVA; see Fig. 4]. This monotonic rise in additive scaling along the ventral pathway is consistent with previous reports in human visual cortex (Kastner et al. 1998; O'Connor et al. 2002; Ress et al. 2000) and might be driven by increasing receptive field size and a corresponding increase in the amount of within-receptive field competition, which is thought to play a critical role in determining the magnitude of attentional modulations (Desimone and Duncan 1995; Kastner and Ungerleider 2001; Kastner et al. 1998).

Fig. 4.

Additive scaling parameter of best-fitting Gaussian function in areas (V1–hV4). Error bars reflect ±1SE across subjects.

We next used an information-theoretic measure—mutual information (MI)—to identify those voxels that are theoretically most representative of changes within specific subsets of orientation-selective neurons (see Using MI as a criterion to select representative voxels in methods; Borst and Theunissen 1999; Cover and Thomas 1991; Fuhrmann Alpert et al. 2007; Panzeri et al. 2008; Serences et al. 2009). A three-way repeated measures ANOVA with visual area (V1–hV4), attention (attended, unattended), and MI bin (first to fourth quartiles) revealed an overall increase in the additive scaling parameter with attention [F(1,6) = 28.5, P < 0.002; see Fig. 5] and an increase in the additive scaling parameter with increasing MI [F(3,18) = 16.9, P < 0.001]; this later modulatory effect of MI on additive scaling was more pronounced in later visual areas (e.g., V3v, hV4) compared with earlier areas [three-way interaction between attention, MI bin, and visual area: F(9,54) = 3.01, P < 0.01; see Fig. 6]. In addition, attention led to significant multiplicative scaling in high-MI voxels [two-way interaction between attention and MI bin: F(3,18) = 7.00, P < 0.005; see Fig. 7]; however, the three-way interaction between attention, MI bin, and visual area did not approach significance [F(9,54) = 1.14, P = 0.35], suggesting a qualitatively similar pattern in all regions. Finally, no significant changes in bandwidth scaling were observed with attention [Supplemental Fig. S3; attention × MI interaction, collapsed across visual areas: F(3,18) = 1.45, P = 0.26], which is perhaps not surprising given similar results in previous single-unit recording studies (e.g., McAdams and Maunsell 1999) and the notion that a decrease in bandwidth does not always benefit the quality of a population code (Series et al. 2004).

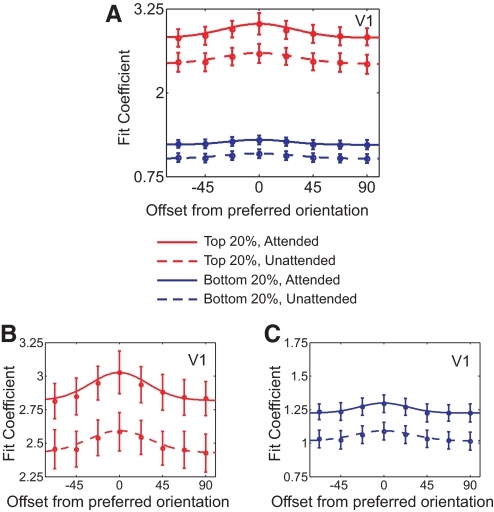

Fig. 5.

A: tuning functions for top 25% (red) and bottom 25% (blue) of voxels in V1 ranked by MI score, with attention (solid curves) and without attention (dotted curves). Tuning functions of high-MI voxels (red lines; also see B) show significant multiplicative and additive scaling, whereas low-MI voxels show primarily additive scaling (blue lines; also see C and Figs. 6 and 7). Note that B and C have been derived from A, to better highlight the difference in shape between the VTFs from high-MI and low-MI voxels (with y-axis of both B and C covering equal range to permit a direct comparison). Error bars reflect ±1SE across subjects.

When considering high-MI voxels, which we hypothesize are the most representative of underlying neural activity, the effect of multiplicative scaling becomes more pronounced compared with that of additive scaling (∼34% vs. ∼21% change in respective parameter estimates with attention, averaged across all visual areas). This change in the multiplicative scaling parameter is roughly comparable with that found by a classic single-unit study of spatial attention (McAdams and Maunsell 1999a,b), where a 23% average increase in multiplicative scaling was observed in V4 neurons.

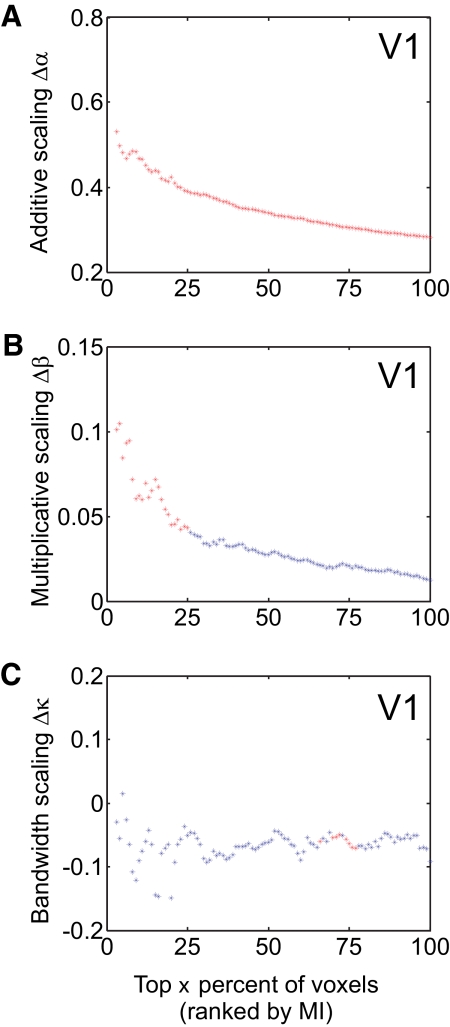

Although we sorted the data into four equinumerous MI bins for the main analysis—so that enough voxels would be in each bin to yield reliable VTF estimates—the magnitude of additive and multiplicative scaling with attention seems to approximately increase monotonically with increasing MI (Fig. 8 and Supplemental Figs. S6 and S12), which we posit is explained by the fact that more homogeneous voxels (indexed by higher MI values) should more accurately reflect attention-induced scaling in underlying neuronal tuning functions (see simulations in Supplemental Fig. S2).

Fig. 8.

A: additive scaling. B: multiplicative scaling. C: bandwidth scaling (attended minus unattended) for voxels in V1 ranked by their MI score. Each point on the x-axis depicts an aggregation of top x% of voxels ranked by their MI score. Corresponding y-axis depicts the mean additive scaling, multiplicative scaling, and bandwidth scaling with attention for mean voxel tuning function of that group. Red color indicates data points that reached significance by repeated measures t-test (P < 0.05). Data points for which mean root mean square error (RMSE) of fit (across subjects) deviated >2SDs from overall RMSE mean (across all subjects and data points) were excluded; this was only an issue for the smallest aggregation of high-MI voxels (< top 3%).

The observed multiplicative scaling of responses with attention should theoretically increase MI by increasing the dynamic range of the BOLD response (see Relationship between attentional gain and MI in methods). However, it is important to directly evaluate whether MI actually increases with attention because an increase in MI is influenced not only by multiplicative scaling but also by the noise characteristics of the responses. Thus we next used MI to evaluate the amount of information conveyed by the population response profiles. First, MI was estimated in each voxel using responses evoked only by unattended stimuli and then the voxels were rank-ordered by their respective value of MI. As outlined previously, voxels with high MI are postulated to be more homogeneous and thus representative of underlying neural populations (see Using MI as a criterion to select representative voxels in methods). When we computed the ratio between each voxel's normalized MI for attended stimuli and unattended stimuli (see Normalized MI in methods); this ratio was >1 for the most representative voxels (see Fig. 9), indicating that spatial attention increases the amount of information carried by BOLD responses (∼25% increase; for a more conservative cross-validated version of the same analysis, see Supplemental Fig. S13). Supplemental Fig. S9 shows where in the cortex the most informative voxels were found in a set of representative subjects.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we used fMRI and feature-selective VTFs to show that spatial attention increases the MI of population response profiles within regions of early visual cortex, primarily by inducing a multiplicative scaling of feature-selective neural tuning functions. If early visual cortex can be thought of as a representational screen on which external visual stimuli get projected and encoded by millions of tiny sensors, then the implication of our finding is that attention effectively increases the bit depth of the information encoded about the stimulus. This increase in bit depth with attention in early visual areas should enable later areas that integrate this information to operate more efficiently, thereby supporting faster and more accurate perceptual decisions (Ditterich et al. 2003; Jazayeri and Movshon 2006; Newsome et al. 1989; Shadlen and Newsome 2001).

MI fulfills two main roles in the current study: 1) MI is used to identify the most informative voxels, which we posit are also the most homogeneous and thus representative of underlying neural populations; and 2) MI provides a means of evaluating how cognitive manipulations, such as spatial deployments of attention, can systematically influence the amount of information encoded about behaviorally relevant stimuli. Since we use MI for the dual purpose not only for selecting highly representative voxels but also for observing changes in the information content of these voxels with attention, we were careful to avoid nonindependence errors. This is especially important in the present context because MI is positively correlated with the multiplicative scaling parameter of a VTF. To avoid issues of circularity, we used independent selection and evaluation phases to first select high-MI voxels and then to evaluate the influence of attention on their response profiles. The MI score of a voxel was calculated using data from all scans save one (selection phase) and the VTFs were computed using data from the remaining scan (evaluation phase) and this process was iterated through all unique combinations of holding-one-scan-out. Similarly, for analysis of the change in MI with attention (Fig. 9), we rank-ordered voxels based on MI derived from unattended stimuli only and then computed the relative increase in MI due to attention (a further split-half analysis was done as well; see Supplemental Fig. S13). The use of a cross-validation procedure ensures that task-independent machine noise was not responsible for the observed attentional effects. Given these measures and the fact that machine noise cannot systematically and significantly vary between attended and unattended perceptual states, we conclude that the data presented here reflect attentional modulations of BOLD signals and are not due to any selection bias or nonindependence errors in our methodology.

The observation of multiplicative scaling in the most informative voxels is consistent with previous single-unit studies in primates (McAdams and Maunsell 1999). On the other hand, the extremely large additive scaling factors we report (see Fig. 6) are not typically observed at the single-unit level, where such effects are generally modest. However, our data and simulations suggest a resolution to this apparent discrepancy. Consider a hypothetical voxel that contains a heterogeneous distribution of orientation-selective neurons. Such a voxel will have poor selectivity and should produce a relatively flat tuning function. Here, a purely multiplicative scaling at the single-unit level would manifest as a feature nonspecific (additive) increase in BOLD activation. For example, attending to 45° should primarily boost the firing rate of neurons tuned to 45°, which will produce heightened activation in the voxel. However, because the voxel contains an equal number of neurons that prefer every other orientation, attending to a different orientation (e.g., 90°, 135°, etc.) should produce an equivalent increase in the activation level. Thus when measured at the coarse spatial resolution afforded by fMRI, multiplicative scaling in a VTF will likely be underestimated and, more important perhaps, translated into a response that appears additive. The magnitude of this “smearing” should increase as the distribution of neural tuning preferences within a voxel becomes more uniform (see simulation results; Supplemental Fig. S2). Note that we are not disputing the existence of additive scaling per se, but simply suggesting that estimates based on fMRI might be generally skewed in favor of additive over multiplicative scaling. In contrast, using an information-theoretic methodology allowed us to distill a subset of voxels that likely captured changes in a more homogeneous distribution of orientation-selective neurons, thereby providing a better window into the nature of attentional modulations in neuronal populations. Accordingly, the more informative voxels showed clear signs of multiplicative scaling, in line with most single-unit studies. Therefore we stress that choosing the most representative voxels is key to improving the precision of inferences based on fMRI data and MI provides such a criterion for voxel selection.

The role of multiplicative scaling in increasing the precision of population codes is relatively straightforward: it increases the mean dynamic range of responses to the feature set, thereby increasing the information content of neural representation (Butts and Goldman 2006; Doya et al. 2007). However, the role of additive scaling is not immediately apparent. From an information-theoretic perspective, a uniform translation of a tuning function (without any other accompanying changes in signal characteristics) should not affect the coding precision of that tuning function (Cover and Thomas 1991). Neuronal noise in visual cortex is typically thought to be nearly Poisson in nature (Averbeck et al. 2006; Shadlen and Newsome 1994). This implies that if there was a feature-nonspecific increase in signal (additive scaling), noise would not increase proportionately (ΔNoise ∝ Δ√Signal), leading to an increase in the SNR of individual responses (Mitchell et al. 2007). However, there is a disconnect when analyzing the SNR of single responses and the MI of population response profiles. The MI of a tuning curve, whether neural or voxel-based, depends not only on the noise characteristics of single responses (noise entropy) but also on the mean dynamic range of responses (total entropy; see methods). Thus a pure additive scaling that increases the SNR of single-unit responses would ultimately increase the noise entropy without increasing the mean dynamic range (yielding no net improvement in information content). On the other hand, multiplicative scaling of tuning curves would simultaneously increase the mean dynamic range of responses and increase the noise in responses, the benefit of the former outweighing the detriment of the latter.

When comparing Figs. 8 and 9, the observed increase in MI with attention within high-MI voxels seems almost equally well correlated with additive scaling as it is with multiplicative scaling. However, it is unlikely that additive scaling caused the observed attention-related increase in MI on theoretical grounds (see preceding text) and because there was no attention-related increase in the information content of the lowest-MI voxels, even though these same voxels showed significant additive scaling (compare Figs. 8 and 9 and Supplemental Figs. S12 and S13). Thus additive scaling alone is not sufficient to induce a relative increase in MI with attention. Instead, the ratio of attended-to-unattended MI does not go >1 until multiplicative gain becomes evident in the higher-MI voxels (toward the left-hand side of Fig. 9). Therefore the observed increase in MI is more likely related to multiplicative scaling as opposed to additive scaling and our data do not appear to shed light on the functional role of additive scaling in influencing the information content of population codes per se.

MI possesses the property that it is directly proportional to the amplitude, or the multiplicative scaling parameter, of the VTFs. However, even though we observed a multiplicative scaling that accompanied an increase in MI with attention, we cannot conclude that the increase in MI was entirely due to the multiplicative scaling of the tuning function. First, the noise entropy component H(B|Θ) of MI can also independently influence the overall value of MI, so it is possible that part of the increase in MI is related to an attention-related reduction in trial-by-trial noise within single units, as well as an attention-related decorrelation across neurons on a within-trial basis (Cohen and Maunsell 2009; Mitchell et al. 2007, 2009). Since we cannot make precise measurements of neural noise using our methodology, we cannot separate the proportion of MI attributable to an increase in total entropy with multiplicative scaling and the proportion attributable to changes in noise entropy. Second, Connor et al. (1996, 1997) showed that spatial attention can shift the spatial receptive field of neurons toward a relevant stimulus, effectively increasing the number of responsive cells (Hamker et al. 2008; Womelsdorf et al. 2006, 2008). Given certain conditions, such as when opposite-tuned neurons are correlated, an increase in the number of responsive neurons can increase the quality of encoding (Abbott and Dayan 1999; Shamir and Sompolinsky 2006). Thus although multiplicative gain is one factor that should increase MI, noise decorrelation and shifting of spatial receptive fields may play an important role as well.

A source of continuing controversy regards the nature of attentional modulation of contrast response functions (CRFs; e.g., Reynolds and Heeger 2009). Based on our results, our assertion that spatial attention induces both multiplicative scaling and additive scaling seems to be in direct conflict with previous studies that found only additive scaling of the CRF (Buracas and Boynton 2007). One might also interpret multiplicative scaling in VTFs to be evidence that spatial attention induces response gain or activity gain on the CRF (Williford and Maunsell 2006). However, the present experiment was conducted at a single-contrast level and, even though we found a significant multiplicative scaling, we cannot determine whether the magnitude of this multiplicative scaling remains constant across all contrast levels. If it remains constant or increases, then a response gain of the CRF would be expected; otherwise, either an additive gain, activity gain, or a contrast gain of the CRF might be induced, depending on the exact nature of the relationship between multiplicative scaling and contrast (and other factors as well, such as the relationship between stimulus size and the size of neural receptive fields; see Reynolds and Heeger 2009). Thus our results do not directly address this issue and further experiments will be required to specify the exact relationship between attentional gain at the level of VTFs and attentional modulations in CRFs.

General conclusions

Here, we provide evidence that spatial attention improves the information content of population responses by inducing multiplicative scaling of population response profiles, hitherto undocumented in human visual cortex. This multiplicative scaling should theoretically improve the encoding precision of population codes that represent the features of a relevant stimulus and our data provide empirical support for this role of spatial attention in perception.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R21-MH-083902 to J. T. Serences.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. A. De Vries, E. Awh, C. McKenzie, and G. Boynton for providing feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Abbott LF, Dayan P. The effect of correlated variability on the accuracy of a population code. Neural Comput 11: 91–101, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Latham PE, Pouget A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 358–366, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst A, Theunissen FE. Information theory and neural coding. Nat Neurosci 2: 947–957, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton GM. Attention and visual perception. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 465–469, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ. Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci 16: 4207–4221, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH. Clustering of response selectivity in the medial superior temporal area of extrastriate cortex in the macaque monkey. Vis Neurosci 15: 553–558, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buracas GT, Boynton GM. The effect of spatial attention on contrast response functions in human visual cortex. J Neurosci 27: 93–97, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts DA, Goldman MS. Tuning curves, neuronal variability, and sensory coding. PLoS Biol 4: e92, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Attention improves performance primarily by reducing interneuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci 12: 1594–1600, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CE, Gallant JL, Preddie DC, Van Essen DC. Responses in area V4 depend on the spatial relationship between stimulus and attention. J Neurophysiol 75: 1306–1308, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CE, Preddie DC, Gallant JL, Van Essen DC. Spatial attention effects in macaque area V4. J Neurosci 17: 3201–3214, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover TM, Thomas JA. Elements of Information Theory. New York: Wiley, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Abbott LF. Theoretical Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Desimone R, Duncan J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu Rev Neurosci 18: 193–222, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditterich J, Mazurek ME, Shadlen MN. Microstimulation of visual cortex affects the speed of perceptual decisions. Nat Neurosci 6: 891–898, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doya K, Ishii S, Pouget A, Rao RPN. Bayesian Brain: Probabilistic Approaches to Neural Coding. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA, Rumelhart DE, Wandell BA, Lee AT, Glover GH, Chichilnisky EJ, Shadlen MN. fMRI of human visual cortex (Abstract). Nature 369: 525, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann Alpert G, Sun FT, Handwerker D, D'Esposito M, Knight RT. Spatio-temporal information analysis of event-related BOLD responses. NeuroImage 34: 1545–1561, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols TE. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. NeuroImage 15: 870–878, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitelman DR. ILAB: a program for postexperimental eye movement analysis. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 34: 605–612, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamker FH, Zirnsak M, Calow D, Lappe M. The peri-saccadic perception of objects and space. PLoS Comput Biol 4: e31, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, Pietrini P. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293: 2425–2430, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JD, Rees G. Predicting the orientation of invisible stimuli from activity in human primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci 8: 686–691, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger DJ, Huk AC, Geisler WS, Albrecht DG. Spikes versus BOLD: what does neuroimaging tell us about neuronal activity? Nat Neurosci 3: 631–633, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Anatomical demonstration of columns in the monkey striate cortex. Nature 221: 747–750, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri M, Movshon JA. Optimal representation of sensory information by neural populations. Nat Neurosci 9: 690–696, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani Y, Tong F. Decoding the visual and subjective contents of the human brain. Nat Neurosci 8: 679–685, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K, Shapley RM, Sompolinsky H. Information tuning of populations of neurons in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 24: 3726–3735, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, De Weerd P, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Mechanisms of directed attention in the human extrastriate cortex as revealed by functional MRI. Science 282: 108–111, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Pinsk MA, De Weerd P, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Increased activity in human visual cortex during directed attention in the absence of visual stimulation. Neuron 22: 751–761, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. The neural basis of biased competition in human visual cortex. Neuropsychologia 39: 1263–1276, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay KN, Naselaris T, Prenger RJ, Gallant JL. Identifying natural images from human brain activity. Nature 452: 352–355, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Ullman S. Shifts in selective visual attention: towards the underlying neural circuitry. Hum Neurobiol 4: 219–227, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojadinovic I. On the use of mutual information in data analysis: an overview. In: ASMDA 2005 Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Applied Stochastic Models and Data Analysis, May 17–20, 2005, Brest, France Hoboken, NJ: Wiley–InterScience, 2005, vol. 21, p. 738–747 [Google Scholar]

- Lagarias JC, Reeds JA, Wright MH, Wright PE. Convergence properties of the Nelder–Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J Optim 9: 112–147, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK. The underpinnings of the BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging signal. J Neurosci 23: 3963–3971, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 412: 150–157, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Chelazzi L, Hillyard SA, Desimone R. Neural mechanisms of spatial selective attention in areas V1, V2, and V4 of macaque visual cortex. J Neurophysiol 77: 24–42, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay DJC. Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Trujillo JC, Treue S. Feature-based attention increases the selectivity of population responses in primate visual cortex. Curr Biol 14: 744–751, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams CJ, Maunsell JH. Effects of attention on orientation-tuning functions of single neurons in macaque cortical area V4. J Neurosci 19: 431–441, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Differential attention-dependent response modulation across cell classes in macaque visual area V4. Neuron 55: 131–141, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Spatial attention decorrelates intrinsic activity fluctuations in macaque area V4. Neuron 63: 879–888, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J, Desimone R. Selective attention gates visual processing in the extrastriate cortex. Science 229: 782–784, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB. The columnar organization of the neocortex. Brain 120: 701–722, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevado A, Young MP, Panzeri S. Functional imaging and neural information coding. NeuroImage 21: 1083–1095, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome WT, Britten KH, Movshon JA. Neuronal correlates of a perceptual decision. Nature 341: 52–54, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DH, Fukui MM, Pinsk MA, Kastner S. Attention modulates responses in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nat Neurosci 5: 1203–1209, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeri S, Magri C, Logothetis NK. On the use of information theory for the analysis of the relationship between neural and imaging signals. Magn Reson Imaging 26: 1015–1025, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeri S, Senatore R, Montemurro MA, Petersen RS. Correcting for the sampling bias problem in spike train information measures. J Neurophysiol 98: 1064–1072, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Long F, Ding C. Feature selection based on mutual information: criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 27: 1226–1238, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Snyder CR, Davidson BJ. Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol 109: 160–174, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget A, Dayan P, Zemel RS. Inference and computation with population codes. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 381–410, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ress D, Backus BT, Heeger DJ. Activity in primary visual cortex predicts performance in a visual detection task. Nat Neurosci 3: 940–945, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JH, Heeger DJ. The normalization model of attention. Neuron 61: 168–185, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz M, Buracas GT, Boynton GM. Global effects of feature-based attention in human visual cortex. Nat Neurosci 5: 631–632, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Rajimehr R, Kim BW, Ekstrom LB, Vanduffel W, Tootell RB. The radial bias: a different slant on visual orientation sensitivity in human and nonhuman primates. Neuron 51: 661–670, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences JT, Boynton GM. Feature-based attentional modulations in the absence of direct visual stimulation. Neuron 55: 301–312, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences JT, Saproo S, Scolari M, Ho T, Muftuler LT. Estimating the influence of attention on population codes in human visual cortex using voxel-based tuning functions. NeuroImage 44: 223–231, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Dale AM, Reppas JB, Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Brady TJ, Rosen BR, Tootell RB. Borders of multiple visual areas in humans revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Science 268: 889–893, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Series P, Latham PE, Pouget A. Tuning curve sharpening for orientation selectivity: coding efficiency and the impact of correlations. Nat Neurosci 7: 1129–1135, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Noise, neural codes and cortical organization. Curr Opin Neurobiol 4: 569–579, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Neural basis of a perceptual decision in the parietal cortex (area LIP) of the rhesus monkey. J Neurophysiol 86: 1916–1936, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir M, Sompolinsky H. Implications of neuronal diversity on population coding. Neural Comput 18: 1951–1986, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swisher JD, Gatenby JC, Gore JC, Wolfe BA, Moon CH, Kim SG, Tong F. Multiscale pattern analysis of orientation-selective activity in the primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 30: 325–330, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treue S, Martinez Trujillo JC. Feature-based attention influences motion processing gain in macaque visual cortex. Nature 399: 575–579, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsotsos JK, Culhane SM, Wai WYK, Lai Y, Davis N, Nuflo F. Modeling visual attention via selective tuning. Artif Intell 78: 507–545, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Williford T, Maunsell JH. Effects of spatial attention on contrast response functions in macaque area V4. J Neurophysiol 96: 40–54, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Pieper F, Treue S. Dynamic shifts of visual receptive fields in cortical area MT by spatial attention. Nat Neurosci 9: 1156–1160, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Treue S. Receptive field shift and shrinkage in macaque middle temporal area through attentional gain modulation. J Neurosci 28: 8934–8944, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.