Abstract

The efflux pump inhibitor phenyl-arginine-β-naphthylamide (PAβN) was paired with iron chelators 2,2′-dipyridyl, acetohydroxamic acid, and EDTA to assess synergistic activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation. All of the tested iron chelators synergistically inhibited P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation with PAβN. PAβN-EDTA showed the most promising activity against P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an important opportunistic pathogen that can cause a wide range of human infections (4). P. aeruginosa is notorious for its tolerance to antimicrobial agents and continues to cause a serious public health problem worldwide (1). The intrinsic multidrug resistance of P. aeruginosa is due, to a large extent, to the expression of efflux pump systems, which include MexAB-oprM, MexXY-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN (14). These efflux systems are reported to promote the export of antibiotics, organic solvents, biocides, and dyes (14). Recently, efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs), which specifically target the efflux activity and pump components, have been identified and proposed as novel agents to combat drug efflux mechanisms of pathogen (10). For example, phenyl-arginine-β-naphthylamide (PAβN) has been reported to be an efficient EPI for P. aeruginosa, as it can potentiate fluoroquinolone activity in resistant P. aeruginosa strains (9).

Among all of the reported P. aeruginosa Mex efflux systems, MexAB-OprM is the only system that is expressed constitutively in cells grown in standard laboratory media (15). This suggests that the export of antimicrobial agents is not the primary function of the MexAB-OprM efflux system. The MexAB-OprM system was identified initially by growing P. aeruginosa in iron-depleted minimal medium containing 2,2′-dipyridyl (Dipy) (13). In that study, Poole and colleagues reported that MexAB-OprM is overexpressed under severe iron limitation conditions, suggesting that the MexAB-OprM system plays an essential role for P. aeruginosa survival under iron limitation conditions (13). The study thus suggests that the combination of efflux inhibitors and iron chelators synergistically inhibits P. aeruginosa growth. In the present study, we evaluated the synergistic activities of EPI with iron chelators against P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation.

The wild-type P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (7) and two isogenic mutants, pvdA (deficient in the synthesis of the iron siderophore pyoverdine [18]) and mexAB-oprM (deficient in the synthesis of the entire MexAB-OprM efflux pump [11]) were used in this study. Bacterial strains were cultivated in AB minimal medium supplemented with 30 mg/liter glucose (5). The AB minimal medium is an iron-restricted medium that promotes the production of the iron siderophore pyoverdine in P. aeruginosa (17). Stock solutions of 100 mg/ml Dipy (Sigma-Aldrich) in ethanol, 100 mg/ml acetohydroxamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) in water, and 100 mg/ml EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) in water were kept at 4°C until use. A stock solution of 10 mg/ml PAβN (Sigma-Aldrich) in water was kept at −20°C until use. The growth-inhibitory assay was performed by growing P. aeruginosa strains in 96-well microtiter dishes. Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa strains were diluted 100 times in freshly prepared medium containing an appropriate concentration of PAβN. Diluted cultures (100 μl) were added to each well of the 96-well microtiter dishes. Iron chelators (Dipy, acetohydroxamic acid, and EDTA) were added to cultures in the 96-well microtiter dishes in 2-fold dilution series. Culture dishes were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the optical densities of the cultures were recorded at 600 nm using a VICTOR3 plate reader (Perkin-Elmer). The evaluation of the growth-inhibitory effect at each drug concentration was monitored in triplicate assays. Biofilms were cultivated as previously described (3) by partially immersing coverslips in green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged PAO1 (17) cultures in Falcon tubes in the presence of different compounds. The ciprofloxacin MICs for P. aeruginosa in the absence or presence of PAβN and/or iron chelators were determined by a serial dilution assay.

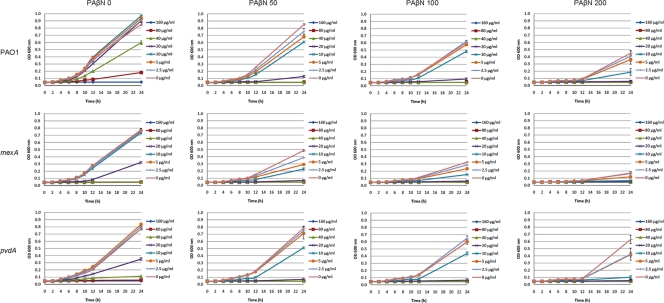

The growth of P. aeruginosa PAO1 was reduced significantly at concentrations of more than 200 μg/ml PAβN and 80 μg/ml Dipy, respectively (Fig. 1, first row). We observed clear synergistic effects from the combination of PAβN and Dipy. A concentration of 100 μg/ml PAβN significantly inhibited the growth of PAO1 in the presence of 20 μg/ml Dipy, and similar inhibition was obtained with a combination of 50 μg/ml PAβN and 40 μg/ml Dipy (Fig. 1, first row).

FIG. 1.

Growth of P. aeruginosa wild-type PAO1, mexAB-oprM mutant, and pvdA mutant in the presence of different PAβN-Dipy combinations. The optical densities of the cultures at 600 nm (OD 600) were recorded after 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h of incubation at 37°C. Each value represents the means and standard deviations from three wells of the microtiter dishes.

The synergistic effects of PAβN and Dipy on an mexAB-oprM mutant also were tested. The mexAB-oprM mutant was more sensitive than the wild-type PAO1 strain to Dipy and PAβN individually as well as to the combination of the two (Fig. 1, second row). Dipy at 40 μg/ml completely inhibited the growth of mexAB-oprM mutant (Fig. 1, second row) but only partially inhibited the growth of wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 1, first row); 200 μg/ml PAβN reduced the growth of the mexAB-oprM mutant to a very low level (Fig. 1, second row), while it only partially inhibited the growth of wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 1, first row). It also was noticed that PAO1 in the presence of more than 100 μg/ml PAβN was more sensitive to Dipy than the mexAB-oprM mutant in the presence of no PAβN (Fig. 1). This result suggests that the synergistic activities between PAβN and Dipy is only partly associated with PAβN being a MexAB-OprM efflux pump inhibitor. We also tested whether the MexAB-OprM efflux pump is involved in pyoverdine synthesis, since pyoverdine can facilitate the growth of P. aeruginosa under iron-limited conditions (12). The mexAB-oprM mutant was found to produce normal amounts of pyoverdine, and PAβN did not reduce pyoverdine synthesis in the wild-type PAO1 strain (data not shown). The synergistic activities between PAβN and Dipy might partially be due to the ability of PAβN to affect membrane integrity when added at high concentrations (9).

The synergistic action by PAβN and Dipy on a pvdA mutant also was tested. As expected, the pvdA mutant is more sensitive to the iron chelator Dipy (Fig. 1, third row) than the wild-type PAO1 strain (Fig. 1, first row). However, the PAβN and Dipy combination inhibited the growth of the pvdA mutant in the same manner as wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 1), which indicated that the synergistic activities between PAβN and Dipy do not depend on the production of the iron siderophore pyoverdine.

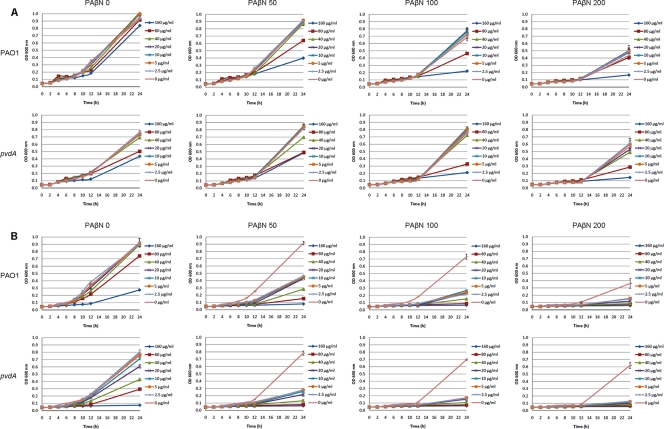

In a further investigation of synergistic actions by PAβN and iron chelators, the effects of acetohydroxamic acid and EDTA combined with PAβN were tested. Weak synergistic activities from PAβN and acetohydroxamic acid added at high concentrations (e.g., 100 μg/ml of PAβN and 80 μg/ml of acetohydroxamic acid) were observed for both P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the pvdA mutant (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, EDTA added at low concentrations (such as 2.5 μg/ml) significantly reduced the growth of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the pvdA mutant when combined with 50 μg/ml PAβN (Fig. 2B). This possibly is due to the fact that EDTA can cause the release of protein-lipopolysaccharide complexes of P. aeruginosa (16). The pvdA mutant is more sensitive to the iron chelator acetohydroxamic acid and EDTA than wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 2). However, combinations of PAβN, acetohydroxamic acid, and EDTA inhibited the growth of the pvdA mutant as well as wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Growth of P. aeruginosa wild-type PAO1 and pvdA mutant in the presence of different PAβN-acetohydroxamic acid combinations (A) and PAβN-EDTA combinations (B). The optical densities of the cultures were recorded after 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h of incubation at 37°C. Each value represents the means and standard deviations from three wells of the microtiter dishes.

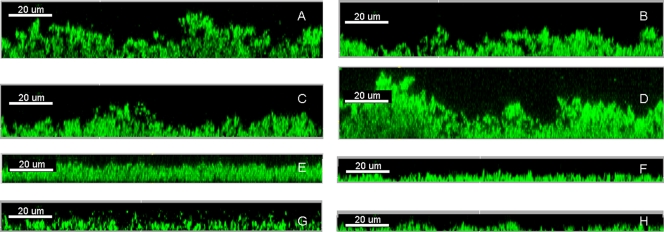

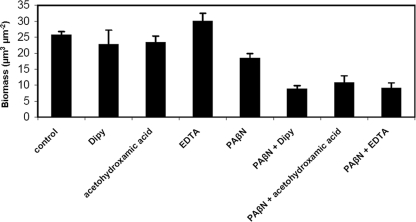

Since both iron uptake and efflux pump activities are reported to play important roles in P. aeruginosa biofilm formation (2, 11, 17, 18), we further tested whether PAβN and iron chelators could synergistically reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm formation. Biofilms of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 were cultivated for 24 h and analyzed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM). To gain statistical significance, three independent biofilm images of each biofilm were acquired by CLSM and then analyzed by the COMSTAT program (6). All three tested iron chelators were found to synergistically reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm formation when added in combination with PAβN (Fig. 3 and 4). However, EDTA was found to increase P. aeruginosa biofilm formation when used alone at the tested concentration (Fig. 3 and 4). This might be due to the fact that EDTA can cause the release of lipopolysaccharide from the cell wall, and the lipopolysaccharide released from the cells might serve as matrix material for the attachment of biofilm cells (8).

FIG. 3.

Biofilm formation at the air-liquid interface of glass slides immersed in culture medium containing medium alone (A), 20 μg/ml Dipy (B), 80 μg/ml acetohydroxamic acid (C), 5 μg/ml EDTA (D), 50 μg/ml PAβN (E), 50 μg/ml PAβN and 20 μg/ml Dipy (F), 50 μg/ml PAβN and 80 μg/ml acetohydroxamic acid (G), and 50 μg/ml PAβN and 5 μg/ml EDTA (H) was observed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy and analyzed by IMARIS (Bitplane AG).

FIG. 4.

Quantification of biofilms by COMSTAT. The results are means of datasets obtained from the analysis of three CLSM images acquired at random positions in each of the biofilms. Standard deviations are shown in parentheses.

Finally, we also tested the effects of combinations of PAβN and iron chelators on the antibiotic sensitivity of P. aeruginosa. We found that PAβN increased the activity of ciprofloxacin 4-fold (MIC = 0.05 μg/ml, down from 0.2 μg/ml) at a concentration of 50 μg/ml in our assay. None of the three tested iron chelators (Dipy at a concentration of 10 μg/ml, acetohydroxamic acid at a concentration of 80 μg/ml, and EDTA at a concentration of 5 μg/ml) affected the activity of ciprofloxacin. The combination of PAβN and the iron chelators at the concentrations mentioned above had the same effect on the activity of ciprofloxacin as PAβN alone, i.e., reducing the MIC from 0.2 μg/ml to 0.05 μg/ml. However, considering the synergistic effects of PAβN and iron chelators on inhibiting the growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa, it seems that combination treatment with PAβN, iron chelators, and conventional antibiotics reduces the risk of the development of antibiotic resistance and tolerance.

In conclusion, we have shown here that synergistic effects from combinations of PAβN and different iron chelators could be obtained against P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation. Our study suggests that combinations of EPIs and iron chelators constitute promising therapeutic interventions against P. aeruginosa infections. Further studies of synergies from combining EPIs and iron chelators against P. aeruginosa growth in vivo should be carried out.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Lundbeck Foundation and a grant from the Danish Council for Independent Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arruda, E. A., I. S. Marinho, M. Boulos, S. I. Sinto, H. H. Caiaffa, C. M. Mendes, C. P. Oplustil, H. Sader, C. E. Levy, and A. S. Levin. 1999. Nosocomial infections caused by multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:620-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banin, E., M. L. Vasil, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11076-11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard, C. S., C. Bordi, E. Termine, A. Filloux, and S. de Bentzmann. 2009. Organization and PprB-dependent control of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa tad Locus, involved in Flp pilus biology. J. Bacteriol. 191:1961-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey, G. P., R. Bolivar, V. Fainstein, and L. Jadeja. 1983. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5:279-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, D. J., and O. Maaløe. 1967. DNA replication and the division cycle in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 23:99-112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heydorn, A., A. T. Nielsen, M. Hentzer, C. Sternberg, M. Givskov, B. K. Ersboll, and S. Molin. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146:2395-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway, B. W., and A. F. Morgan. 1986. Genome organization in Pseudomonas. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 40:79-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leive, L. 1965. Release of lipopolysaccharide by EDTA treatment of E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 21:290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomovskaya, O., M. S. Warren, A. Lee, J. Galazzo, R. Fronko, M. Lee, J. Blais, D. Cho, S. Chamberland, T. Renau, R. Leger, S. Hecker, W. Watkins, K. Hoshino, H. Ishida, and V. J. Lee. 2001. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:105-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagès, J. M., M. Masi, and J. Barbe. 2005. Inhibitors of efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Mol. Med. 11:382-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pamp, S. J., M. Gjermansen, H. K. Johansen, and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2008. Tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is linked to metabolically active cells, and depends on the pmr and mexAB-oprM genes. Mol. Microbiol. 68:223-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole, K., D. E. Heinrichs, and S. Neshat. 1993. Cloning and sequence analysis of an EnvCD homologue in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: regulation by iron and possible involvement in the secretion of the siderophore pyoverdine. Mol. Microbiol. 10:529-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poole, K., K. Krebes, C. McNally, and S. Neshat. 1993. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:7363-7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole, K., and R. Srikumar. 2001. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole, K., K. Tetro, Q. Zhao, S. Neshat, D. E. Heinrichs, and N. Bianco. 1996. Expression of the multidrug resistance operon mexA-mexB-oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mexR encodes a regulator of operon expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watt, S. R., and A. J. Clarke. 1994. Role of autolysins in the EDTA-induced lysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang, L., K. B. Barken, M. E. Skindersoe, A. B. Christensen, M. Givskov, and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2007. Effects of iron on DNA release and biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 153:1318-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, L., M. Nilsson, M. Gjermansen, M. Givskov, and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2009. Pyoverdine and PQS mediated subpopulation interactions involved in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1380-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]