Abstract

The phylogeography of cattle genetic variants has been extensively described and has informed the history of domestication. However, there remains a dearth of demographic models inferred from such data. Here, we describe sequence diversity at 37 000 bp sampled from 17 genes in cattle from Africa, Europe and India. Clearly distinct population histories are suggested between Bos indicus and Bos taurus, with the former displaying higher diversity statistics. We compare the unfolded site frequency spectra in each to those simulated using a diffusion approximation method and build a best-fitting model of past demography. This implies an earlier, possibly glaciation-induced population bottleneck in B. taurus ancestry with a later, possibly domestication-associated demographic constriction in B. indicus. Strikingly, the modelled indicine history also requires a majority secondary admixture from the South Asian aurochs, indicating a complex, more diffuse domestication process. This perhaps involved multiple domestications and/or introgression from wild oxen to domestic herds; the latter is plausible from archaeological evidence of contemporaneous wild and domestic remains across different regions of South Asia.

Keywords: domestication, cattle, demography, modelling, Bos taurus, Bos indicus

1. Introduction

I should think, from facts communicated to me by Mr Blyth, on the habits, voice and constitution etc. of the humped Indian cattle, that these had descended from a different aboriginal stock from our European cattle; and several competent judges believe these latter may have had more than one wild parent. (Charles Darwin. ‘On the Origin of Species’, p.28)

In the light of over 20 years of molecular genetic investigation of diversity within cattle populations it is clear that Darwin and his correspondent Mr Blyth were correct; the divergence between Bos indicus and Bos taurus is too great to have emerged from domestication of a single population of the aurochs, Bos primigenius (Loftus et al. 1994). Mitochondrial sequences have been extensively sampled from diverse populations, including from fossil wild oxen, and have revealed a striking pattern of deeply branching clades with many very similar sequences clustered at each tip (Troy et al. 2001; Edwards et al. 2007; Achilli et al. 2009). This is interpreted as the signature of a discrete number of divergent wild ox populations contributing to the domestic pool; in each of B. indicus and B. taurus, two relatively similar clades predominate, with other types being found only in fossils or at very small frequencies in the domestic pool. Thus, domestication seems most likely to have been a limited sampling of the wild ox, with at least two (maybe more) episodes, one focused around the near East and one further East in the Indian subcontinent.

However, the nature of the domestication process forms an open question. The number of animals captured, its duration and whether it was discrete or continuous over a long period remain unknown. Whereas overall mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) evidence does seem to point towards some restriction in place and time in domestication events (Machugh & Bradley 2001), low-frequency phylogenetically outlying haplotypes betray some degree of secondary introgression from the wild (Achilli et al. 2008, 2009; Stock et al. 2009). These must be regarded as suggesting much greater secondary autosomal contribution. Incorporation of wild matrilines must always have involved difficult captures; alternatively, input to the domestic pool via wild inseminations would have immediately resulted in semidomestic hybrids and seems clearly a more likely, and hence frequent, type of introgression to have occurred within domestic history.

The recent genomewide analysis by the bovine HapMap consortium found high levels of genetic diversity in all cattle breeds surveyed, exceeding those found in human and dog populations, and revealed more than twice as much nucleotide diversity in one indicine breed in comparison to B. taurus breeds (Marth et al. 2003; Ostrander & Wayne 2005; Gibbs et al. 2009; Lewin 2009). These data agree with previous findings from major histocompatibility complex (MHC) allele diversity by Vila et al. (2005), which strongly argue that the allele spectra in many domestic species today are not depleted in diversity, as might be expected from a traditional view of early domestic history involving a severe capture bottleneck. Additionally, it has been noted that levels of protein polymorphism in cattle, as assayed by classical methods, are typical for mammals (Lenstra & Bradley 1999), showing no dramatic indication of a restricted capture of diversity from the wild.

In contrast, two recent analyses suggest discernible population genetic signatures of the domestication process within modern cattle. Estimates of past effective population sizes derived from examining linkage disequilibrium decay with distance, using a medium density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) panel, indicate a large predomestication population with an approximately 50-fold decline at domestication followed by a further decline with the formation of modern breeds (Goddard & Hayes 2009). Also, Finlay et al. (2007) examined mtDNA datasets from four domestic Bovidae (cattle, mithan, yak and water buffalo) using the Bayesian approach to the coalescent process implemented in BEAST, and compared these to two wild bovid samples (bison and African buffalo). In each domestic sample, a sharp recent increase in effective population size was estimated that seems consistent with the timeframe of domestic history. That this was related to human capture and taming was suggested by the observation that neither wild bovine showed this phenomenon.

Here, we sought to model the demographic history (and hence illuminate the domestication process) of cattle populations sampled from three continents, choosing, as far as possible, breeds known from prior analysis to display only limited or no recent admixture between ancestral populations. We analysed sequence diversity assayed at 17 genes and explored plausible demographic models by comparing the unfolded allele frequency spectra with those generated under simulations using a diffusion approximation method. These loci include genes involved in immunity and some have indication of adaptive history: the initial rationale for their sequencing (Freeman et al. 2008). As such they represent an imperfect dataset for demographic modelling but we argue that this remains an interesting exercise given the scale of the dataset. In particular, any biases from locus choice should be similar in B. indicus and B. taurus and our strongest result is that of divergent domestication histories between the cattle subtypes. Our optimal model indicates an early bottleneck plus expansion within B. taurus, a later (possibly domestication-related) bottleneck within B. indicus and, strikingly, a substantial secondary input from local aurochsen to the South Asian domestic pool.

2. Materials and methods

(a). Sequencing

Seventeen genes were fully or partially resequenced in one of two sequencing panels. TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7 and TLR9 were resequenced in a smaller panel made up of five European B. taurus (Charolais, Jersey, Simmental, Friesian and Aberdeen Angus), five African B. taurus (Somba and N'Dama), five B. indicus (Hariana, Sahiwal and Tharparker) and one outgroup species, Bos gaurus (Gaur).

The remaining genes including seven previously described (Freeman et al. 2008) were resequenced in a panel comprising 20 European B. taurus (Aberdeen Angus, Friesian, Norwegian Red, German Black, Highland, Alentejana, Mertolenga, Romagnola, Sikias, Anatolian Black), 11 African B. taurus representing three West African breeds known to have little or no zebu introgression (N'Dama, Somba and Lagune) and 11 Asian B. indicus representing four Indian breeds. In addition, one B. gaurus (Gaur), one Bison bison (Plains Bison) were included in the panel. Only those outgroup sequences for which haplotypes could be determined were used in analyses.

Primers were designed using Primer Select or Primer3. In the case of TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, TLR9 and PRF1, primers were designed to amplify as much coding sequence as possible in a single fragment. In the case of the remaining genes, the sequencing strategy aimed to cover the whole coding sequence, approximately 1 kb of intronic sequence as well as 1 kb of flanking sequence at the 5′ and 3′ end of the gene. The ‘Overlapping Primers’ option of The PCR Suite (Van Baren & Heutink 2004), an interface to Primer 3, was used to design multiple overlapping pairs of primers to amplify MRPL30, MRPS14, MRPS05, FEZL and TNFAIP8L1. The amplification and sequencing of TRIF, CD2, IL2, IL13, ART4 and TYROBP have been described (Freeman et al. 2008).

The genes were amplified and subjected to Sanger sequencing using commercial service providers (Agowa GmbH, Germany) and sequence data were assembled and analysed using the Phred, Phrap and Consed software (Ewing & Green 1998; Ewing et al. 1998; Gordon et al. 1998). Polymorphic sites were identified using Polyphred (Stephens & Scheet 2005) and confirmed visually . PHASE v.2.1.1 (Stephens & Scheet 2005) was used to infer haplotypes and population genetic parameters were estimated using DnaSP (Rozas et al. 2003).

Genes that were completely or partially sequenced in at least a subset of samples from the three continents included: CD2, IL2, IL13, ART4, TYROBP, TRIF, TNFAIP8L1, FEZL, MRPL30, MRPS14, MRPS05, PRF1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9. TLR7 was omitted from all analyses as no polymorphic sites were identified in the region sequenced.

(b). Demographic modelling and inference

The unfolded site frequency spectrum (SFS) is a summary statistic of the data that records the counts, xi, of the number of derived alleles at frequency i in a sample of n chromosomes. We were not interested in ancestral only or fixed sites, so that i ranges from 1 to n–1. The SFS has been a useful tool in understanding how demographic history and selection affects the pattern of genetic variation observed in a sample. Diffusion approximations to the forward model of molecular evolution can be used to derive, or numerically solve for, the expected SFS under various model structures (e.g. different demographic scenarios) and thus one can exploit a likelihood framework for estimating model parameters. A powerful tool for solving diffusion model equations and performing model fitting to frequency spectrum data has been recently developed, called ∂a∂i (Gutenkunst et al. 2009).

Unlike the popular program ms (Hudson 2000), ∂a∂i is based on a forward-time model. Briefly it models the evolution of allele frequencies (governed by a linear diffusion equation) in up to three populations as a function of time t. One of the advantages of ∂a∂i is its flexibility and its computational speed. This software allows one to specify general demographic models with up to three populations and all the same demographic features (including population splitting, admixture, growth, bottlenecks and migration) as ms. It has optimization algorithm capabilities so that one can search for maximum-likelihood estimates for parameters based on the likelihood of the joint SFS. Unlike ms, this software assumes that sites are independent. All customizable settings such as grid spacing and time-step size for the numerical solver were kept at default values.

The software is designed to fit joint frequency spectrum data, a generalization of the frequency spectrum described above (xij is the number of derived alleles at frequency i in population 1 and at frequency j in population 2), but we applied it to two population marginal spectra because of the smaller size of our dataset that would provide only a very poorly sampled two-dimensional joint spectrum. For demographic inference analysis, we extracted the synonymous SNPs from all genes except those for which no outgroup information was available, MRPL30, MRPS05 and MRPS14. For the other loci, the ancestral state was estimated by comparison to either bison or gaur sequence. Where both were available, similar SFS resulted using either comparison.

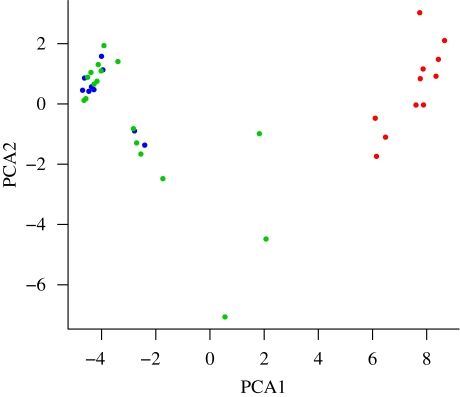

Since we had a collection of samples with varying sample sizes, we needed to adjust the data for the SFS analysis by projecting the data down to a common sample size of 10 chromosomes (Marth et al. 2004). Enforcing a requirement of a minimum of 10 chromosomes per subpopulation per gene, we also discarded TLR9. The remaining data involved 12 genes with a total of 197 synonymous (or intronic or in a UTR region) segregating sites. We aggregated the African and European B. taurus samples, as they were determined to have similar SNP distributions by a principal components analysis (PCA), shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Principal components analysis (PCA). Plot of the first two principal components of allele frequency variation in African European and Indian cattle. Note the clear separation of B. indicus and the intermingling of African and European B. taurus individuals. Red circle, indicus; green circle, Europe taurus; blue circle, African taurus.

(c). Model fitting and parameter inference

Given a demographic model, dependent on demographic parameters such as time of taurus–indicus split, bottleneck size and duration and migration rates, we ran ∂a∂i to generate an expected SFS and then optimized the parameter values by minimizing a χ2-measure of goodness of fit between the data and the model output (the χ2-statistic was chosen as it is standard for goodness-of-fit tests and approximates the more theoretically based Poisson log-likelihood underlying the SFS framework). The final parameters from the minimization routine are point estimates for the demographic parameters. To assign errors to these estimates, we followed the procedure in Gutenkunst et al. (2009): we generated sequences for each gene in the dataset using ms, where the number of segregating sites and sample sizes were set to correspond to the same values in the data, while the demographic model and parameters for ms came from the point estimates. For 74 SFSs generated in this manner, we then re-optimized the fit using ∂a∂i to produce 74 point estimates for the parameters. The standard deviations of each parameter across these 74 estimates were then identified as uncertainty estimates.

To assess goodness of fit, we compare the χ2-measure of fit for the final inferred demographic model to the distribution of χ2-values for the best-fit-simulated datasets under the same model. The χ2-value for the best-fit demographic model is 0.023 which is consistent with the values from simulated datasets (minimum = 0.015, 1st quartile = 0.035, median = 0.056, 3rd quartile = 0.088, maximum = 0.29). Four simulated datasets out of the 74 have lower, and the remaining simulated datasets have higher, χ2-values. This implies that, using the simulated datasets to provide a null distribution, the fit to the real data is not unusually bad and neither is it an example of overfitting.

In order to convert to physical units we estimated the ancestral population size (Na). We used the population mutation rate θ = 4NaμL, where μ was assumed to be the average mammalian rate 2.2E–9 per year (or 11E–9 per generation assuming that one generation is equal to 5 years (Kumar & Subramanian 2002)), and L is the effective sequence length (37 000 base pairs in our case). In a neutral model, θ can be estimated by Watterson's formula (S/∑(1/i)). Alternatively, under the diffusion approach θ can be estimated by ∑(data)/∑(model); (Bustamante et al. 2001). The ∑(data) is simply the observed number of segregating sites and ∑(model) is the sum of the expected SFS using the best-fit parameters of our model. This yields a θ of 23, so that we estimate Na = 23/(4 × 3700 × 11E−9) = 14 127.

3. Results

(a). Sequence diversity

In total, the 37 011 bp of sequence yielded 303 SNPs, giving an average frequency of one SNP every 122 bp. There was a great variation between genes and between populations in terms of the number of SNPs identified, with 50 polymorphic sites being identified in TRIF and none in TLR7. As widely differing numbers of sites were sequenced for each region, it is more useful to consider the SNP frequencies than the absolute number of SNPs identified. Bos indicus showed the highest frequency of polymorphic sites while the African B. taurus showed the lowest. In the African B. taurus, on average a SNP was identified every 370 bp, in European B. taurus a SNP was identified every 204 bp, and in B. indicus a SNP was identified every 167 bp.

No SNPs were identified in TLR7 (826 bp sequenced) within any population. No SNPs were identified in TLR5 in either of the B. taurus populations (412 bp sequenced). Additionally, four other genes showed SNP frequencies of less than one SNP per kilobyte. These were TNFAIP8L1 in African B. taurus (one SNP every 1081 bp), PRF1 in European B. taurus (one SNP every 1107 bp), FEZL in African B. taurus (one SNP every 2141 bp) and IL2 in African B. taurus (one SNP every 3461 bp).

A number of genes showed much higher than average SNP frequencies. The following genes had a SNP frequency of greater than one SNP every 100 bp: ART4 in B. indicus (one SNP every 57 bp), TLR4 in B. indicus (one SNP every 73 bp) and MRPS05 in B. indicus (one SNP every 79 bp) and TLR9 in B. indicus (one SNP every 94 bp).

Table 1 lists summary statistics for each gene sequence within each continental sample. Overall, haplotype diversity is lowest in African B. taurus (11 out of the 16 genes) and highest in B. indicus (10/16). European B. taurus has the highest value for 3/16 and the lowest for 3/16. Although the African B. taurus typically has the lowest haplotype diversity, there are two genes for which it has the highest haplotype diversity. These are TLR9 and MRPS14. Only one gene, TRIF (also known as TICAM1), shows significantly lower than expected haplotype diversity in all three populations.

Table 1.

Sequence summary statistics.

| gene | bp sequenced | population | na | Sb | no. of haplotypesc | haplotype diversity | θ(per site)d | π(per site)e | Tajima's D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART4 | 2157 | Africa | 20 | 6 | 6 | 0.747 | 0.0008 | 0.00096 | 0.721 |

| Europe | 36 | 6 | 6 | 0.783 | 0.0007 | 0.00064 | −0.146 | ||

| India | 22 | 33 | 16 | 0.961 | 0.0042 | 0.00456 | 0.332 | ||

| CD2 | 3752 | Africa | 20 | 13 | 5 | 0.616 | 0.0010 | 0.00099 | 0.051 |

| Europe | 36 | 30 | 10 | 0.846 | 0.0019 | 0.00161 | −0.576 | ||

| India | 22 | 29 | 10 | 0.870 | 0.0021 | 0.00225 | 0.236 | ||

| FEZL | 4282 | Africa | 18 | 2 | 3 | 0.451 | 0.0001 | 0.00013 | −0.192 |

| Europe | 36 | 8 | 7 | 0.633 | 0.0005 | 0.00026 | −1.244 | ||

| India | 22 | 11 | 9 | 0.887 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | −1.018 | ||

| IL2 | 3297 | Africa | 20 | 1 | 2 | 0.268 | 0.0001 | 0.00008 | −0.086 |

| Europe | 36 | 12 | 9 | 0.614 | 0.0008 | 0.00037 | −1.754 | ||

| India | 22 | 7 | 7 | 0.593 | 0.0006 | 0.00042 | −0.769 | ||

| IL13 | 3461 | Africa | 20 | 15 | 9 | 0.653 | 0.0013 | 0.00053 | −2.156 |

| 3461 | Europe | 36 | 15 | 13 | 0.814 | 0.0011 | 0.00076 | −0.998 | |

| India | 22 | 14 | 12 | 0.935 | 0.0012 | 0.00141 | 0.741 | ||

| MRPL30 | 1220 | Africa | 12 | 2 | 2 | 0.303 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | −0.248 |

| Europe | 36 | 9 | 7 | 0.763 | 0.0018 | 0.00213 | 0.582 | ||

| India | 22 | 7 | 5 | 0.468 | 0.0016 | 0.00116 | −0.848 | ||

| MRPS05 | 2455 | Africa | 18 | 11 | 10 | 0.915 | 0.0013 | 0.00179 | 1.363 |

| Europe | 38 | 19 | 10 | 0.728 | 0.0018 | 0.00164 | −0.362 | ||

| India | 22 | 31 | 16 | 0.961 | 0.0035 | 0.00403 | 0.628 | ||

| MRPS14 | 628 | Africa | 22 | 2 | 4 | 0.645 | 0.0009 | 0.00147 | 1.542 |

| Europe | 40 | 1 | 2 | 0.185 | 0.0004 | 0.00029 | −0.307 | ||

| India | 22 | 1 | 2 | 0.247 | 0.0004 | 0.00039 | −0.175 | ||

| PRF1 | 1107 | Africa | 10 | 3 | 2 | 0.200 | 0.0010 | 0.00054 | −1.562 |

| Europe | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0.467 | 0.0003 | 0.00042 | 0.82 | ||

| India | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.733 | 0.0010 | 0.00139 | 1.604 | ||

| TLR2 | 1114 | Africa | 10 | 3 | 4 | 0.644 | 0.0010 | 0.00083 | −0.5067 |

| Europe | 10 | 8 | 5 | 0.756 | 0.0025 | 0.00192 | −1.093 | ||

| India | 10 | 9 | 4 | 0.822 | 0.0029 | 0.00319 | 0.454 | ||

| TLR4 | 1100 | Africa | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0.511 | 0.0006 | 0.00061 | −0.184 |

| Europe | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0.689 | 0.0006 | 0.00093 | 1.439 | ||

| India | 10 | 15 | 5 | 0.822 | 0.0048 | 0.00471 | −0.108 | ||

| TLR5 | 412 | Africa | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0 | ||

| Europe | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| India | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0.533 | 0.0009 | 0.00129 | 1.303 | ||

| TLR9 | 941 | Africa | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.600 | 0.0009 | 0.00128 | 1.753 |

| Europe | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0.250 | 0.0004 | 0.00027 | −1.055 | ||

| India | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0.467 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | 0.83 | ||

| TNFAIP8L1 | 2163 | Africa | 20 | 2 | 3 | 0.358 | 0.0003 | 0.00018 | −0.769 |

| Europe | 36 | 10 | 5 | 0.384 | 0.0011 | 0.00089 | −0.616 | ||

| India | 22 | 6 | 4 | 0.571 | 0.0008 | 0.00078 | 0.096 | ||

| TRIF | 4130 | Africa | 20 | 24 | 5 | 0.442 | 0.0016 | 0.00109 | −1.283 |

| Europe | 36 | 41 | 11 | 0.751 | 0.0024 | 0.00244 | 0.073 | ||

| India | 22 | 22 | 7 | 0.693 | 0.0015 | 0.00186 | 1.027 | ||

| TYROBP | 3966 | Africa | 20 | 8 | 6 | 0.779 | 0.0006 | 0.00055 | −0.137 |

| Europe | 36 | 20 | 12 | 0.657 | 0.0012 | 0.00064 | −1.607 | ||

| India | 22 | 12 | 11 | 0.913 | 0.0008 | 0.00101 | 0.745 |

aThe number of chromosomes in the sample population.

bThe number of segregating sites in the sample population.

cThe number of haplotypes observed in the population.

dThe number of segregating sites, adjusted for sample size, θw (per site).

eThe average number of pair-wise differences, π (per site).

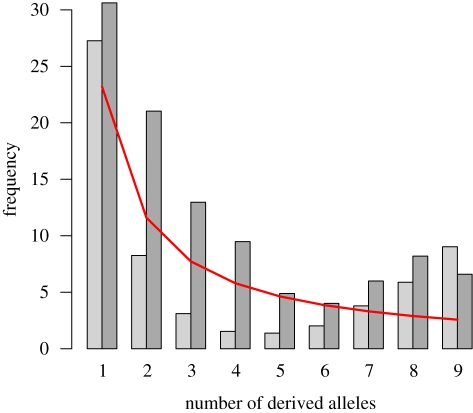

The unfolded SFS for both B. taurus and B. indicus are shown in figure 2. There is an abundance of derived alleles with higher frequencies than expected under neutrality. This SFS is quite different in shape from that obtained by Maceachern et al. (2009) based on 7500 SNPs in Angus and Holstein breeds; especially comparing the remarkably low number of rare SNPs in their data, which was far less than expected under a neutral model. This is most probably owing to the ascertainment bias inherent by genotyping SNPs that have been discovered first in a very small sample. In our analysis European and African B. taurus samples are combined, but even taken separately, we do not see the frequency distribution observed by Maceachern et al. in their analysis (results not shown).

Figure 2.

The site frequency spectra (SFS) for B. taurus and B. indicus samples projected down to a common sample size of 10 chromosomes. The prediced SFS from the neutral model is indicated. Light grey, Bos taurus (Africa, Europe); dark grey, Bos indicus; red, neutral model.

(b). Demographic models

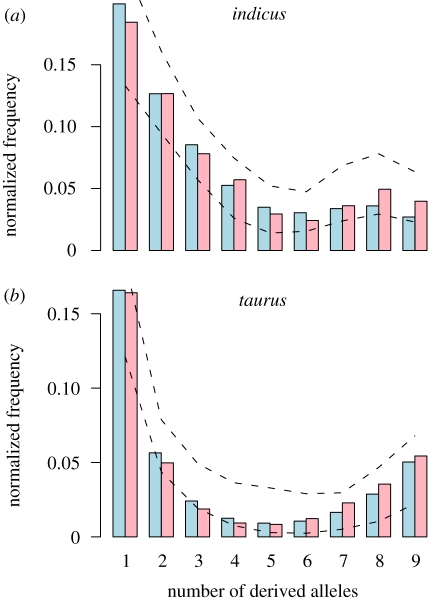

We sought to describe the site frequency data with a demographic model that had a minimum of parameters but which had a good fit and realistically reflected current knowledge regarding cattle demographic history. During the process of refining demographic models, we came to some conclusions concerning what features the model had to contain to correctly capture the observed frequency spectra. First, a bottleneck followed by population growth in the B. taurus population is supported by the data but the estimated time for this bottleneck precedes domestication events. Second, to correctly capture the excess of synonymous-derived alleles at high frequency in the B. taurus and B. indicus spectra, we require some non-zero migration between the species. Third, B. indicus has an unusually slow decay in its SFS, which can be explained by substantial admixture from a wild outgroup derived from an ancient split. There is also evidence of a transitory bottleneck in B. indicus that may overlap with the timeframe of the domestication process. Figure 3 shows the observed and modelled SFS for both samples, including outer five percentile boundaries derived from ms simulations.

Figure 3.

Unfolded SFS simulated under the best-fit model compared with observed SFS for (a) B. indicus and (b) B. taurus. Dotted lines illustrate the upper and lower five percentiles of the projected SFS calculated from ms replicates. (a,b) Blue bar, theory; pink bar, data.

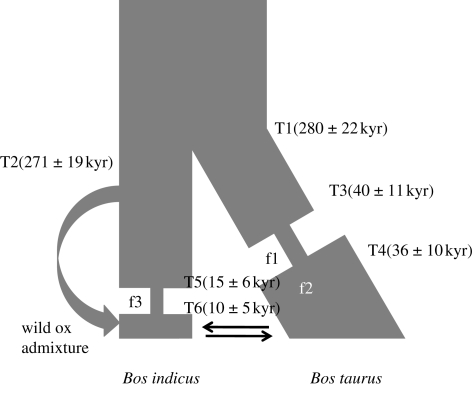

The final demographic model containing 12 parameters and two bottlenecks is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Model for bovine demographic history. Time depth parameters are: T1, divergence time of B. taurus and B. indicus ancestors; T2, split giving a parallel South Asian wild oxen population that later admixes with B. indicus; T3 and T4, beginning and end of a population bottleneck within B. taurus ancestors; T5 and T6, beginning and end of a population bottleneck within B. indicus. f1 and f3 refers to the fractional decrease from the reference ancestral population size Na during the B. taurus and B. indicus bottlenecks and f2 gives the relative size of the recovery B. taurus population. Arrows indicate migration (mi→t from B. indicus to B. taurus and mt→i vice versa). Best-fitting parameter values are given in table 2.

The final model fit for each parameter and standard deviation is shown in table 2 (in genetic units and in years, fixing an ancestral population size at 14 127 and generation time at 5 years). An indication of parameter estimate uncertainties is provided by the standard deviations (in genetic units) of each derived from ms simulations (table 2).

Table 2.

FIT refers to best-fitting estimates from ∂a∂i; mean and s.d. refer to the mean and standard deviation of parameter values of ms simulations. Time depth estimates are in genetic units of 2Na generations where Na is the reference ancestral population size. These are calibrated assuming Na = 14 127 and one generation = 5 years. f1, f2 and f3 indicate relative proportion of Na in population bottlenecks and recovery. mi→t and mt→i are migration parameters indicating proportion of chromosomes per generation that are migrants from one population to another (i → t indicating B. indicus to B. taurus and vice versa). Adm indicates the proportion of wild ox admixture input into B. indicus.

| parameter | FIT (calibrated) | mean | s.d. (calibrated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 1.98 (280 kyr) | 2.102 | 0.155 (22 kyr) |

| T2 | 1.92 (271 kyr) | 2.037 | 0.133 (19 kyr) |

| T3 | 0.282 (40 kyr) | 0.353 | 0.081 (11 kyr) |

| T4 | 0.256 (36 kyr) | 0.263 | 0.071 (10 kyr) |

| T5 | 0.104 (15 kyr) | 0.119 | 0.041 (6 kyr) |

| T6 | 0.07 (10 kyr) | 0.061 | 0.032 (5 kyr) |

| f1 | 0.012 | 0.03 | 0.028 |

| f2 | 1.36 | 1.325 | 0.067 |

| f3 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| mi→t | 0.435 | 0.452 | 0.144 |

| mt→i | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.011 |

| Adm | 0.79 | 0.8 | 0.041 |

In summary, approximately 280 000 years ago the population of B. taurus and B. indicus diverged. Soon after (approx. 270 000 years ago) the model has B. indicus ancestors split from a wild group. These ancestors endured a severe bottleneck commencing about 15 000 years ago and ending roughly 10 000 years ago. Bos indicus are only allowed to recover back to the original population size before the bottleneck but there is a recent, substantial admixture event from the wild population, contributing the majority of the modern genome. Within the B. taurus ancestral population, a severe bottleneck (0.012 of the ancestral population survived) began about 40 000 years ago and was estimated to have ended roughly 36 000 years ago. After this bottleneck there was a recovery (modelled as instantaneous growth) and the population grew to 1.36 of its ancestral size. Migration from B. taurus to B. indicus (mt→i) was low and migration rates from B. indicus to B. taurus (mi→t) were only slightly larger.

4. Discussion

The analysis of demographic history described here has been carried out on populations defined at the continental level, that is, an African B. taurus population, a European B. taurus population and a B. indicus population. These three samples were chosen to represent the products of two separate domestication events (B. indicus and B. taurus) plus a further division between African and European taurus that stretches back at least to the Neolithic (Loftus et al. 1994; Bradley et al. 1996). Interestingly, several lines of evidence robustly suggest that the demographic history of the B. indicus population is markedly different from either of the B. taurus populations.

At a descriptive level, nucleotide diversity seems higher within indicus; in 11 out of 16 loci, π is greatest in B. indicus, and in eight of 16 loci θW is greatest in B. indicus. Haplotype diversity is also consistently higher with 11 of 16 loci giving a highest value in this sample. This strongly suggests divergence in demographic histories between the two taxa.

Our initial modelling approach (not shown) was to assume possible bottlenecks followed by population expansion in the history of each of the three sampled populations. We also allowed migration between continents. Under this approach, the B. taurus allele frequency spectra fitted a demography with a severe bottleneck but this predates by a factor of 2.75 the modelled divergence of African and European cattle which, from other evidence, probably dates to the early domestic period or possibly before (Wendorf & Schild 1994; Bradley et al. 1996; Achilli et al. 2008; Ho et al. 2008). However, the search for a maximum-likelihood fit would not allow a bottleneck within B. indicus history, and an excess of high-frequency-derived alleles in that population suggested a more complex scenario.

To account for this, and given the clear similarity between the B. taurus populations illustrated in a PCA (figure 1), we developed a second three-population model with a single B. taurus population and two B. indicus populations: one a domesticated lineage with a bottleneck and recovery, plus a second parallel wild population that was allowed to mix with the first. This allowed a closer fit of observed and modelled data.

Several features of the best-fitting model are interesting. First, the early and clearly predomestic population bottleneck persists in the ancestral demography of European and African B. taurus. When one assumes an ancestral population size calculated at 14 127 and a generation time of 5 years this maps to between 40 and 36 kyrs ago with s.d. of the order of 11 kyrs. There is uncertainty in this calibration but we note that some estimates of the ancestral population size for wild cattle are larger (Goddard & Hayes 2009), which would push these calendar estimates further into the past. It is possible that this single-modelled bottleneck represents an amalgam of a more variegated demographic history, which perhaps includes a domestication bottleneck. However, it does seem to point primarily toward an earlier episode, perhaps associated with the effects of the glacial period on the West Asian aurochs. Interestingly, ancient DNA analysis of 34 mtDNA sequences sampled from European aurochsen bones also gives a signature of population expansion that concurs with the timeframe of glacial retreat and which, by definition, cannot be a result of the domestication process (Edwards et al. 2007; Ho et al. 2008). We note that an equivalent early population constriction is missing from B. indicus ancestry, probably reflecting a more benevolent glacial ecology within South Asia. Divergence between zebu and taurine mtDNA has been calibrated repeatedly, typically being of the order of hundreds of thousands of years (most recently by Ho et al. (2008) as between 84–219 kyr ago). Our estimate of 280 kyr with s.d. 22 kyr for ancestral separation is of similar order.

The strongest contrast between West and South Asian domestic history lies in the modelled complexity within the domestication process. The comparatively large haplotypic diversity and distinctive allele frequency spectrum within B. indicus seem to defy a uniform domestication narrative. Whereas the best-fitting model allows a B. indicus ancestral bottleneck that lies conceivably within the domestication timeframe, this requires a majority input (approx. 80%) into the domestic indicine gene pool from wild admixture. We are restricted here from examining more complex models but it should be noted that this may not exclude alternatives such as multiple strands of wild ox ancestry arising within B. indicus ancestry through two or more independent domestications.

Some geographical and genetic complexity within B. indicus domestication does seem likely from prior work. mtDNA sequencing has described two clusters of indicine mtDNA haplotypes and these have a non-random distribution when samples from east and west are compared (Baig et al. 2005; Lai et al. 2006; Magee et al. 2007). This is argued as suggesting that more than one domestication process may have given rise to B. indicus. Domestic cattle first appear in the Baluchistan early agricultural center, Mehrgarh, 8000–7000 bp. This is in the context of other domesticates (goats, barley and wheat) that probably diffused eastwards from the Fertile Crescent (Fuller 2006). However, artistic representations and thoracic vertebrae with morphology typical of zebu have allowed Meadow (1987) to argue that these early cattle were B. indicus of local origin. A transition in the nature of Bos bone finds (abundance, size) points towards this as a plausible primary centre for domestication of zebu from the South Asian aurochs, Bos primigenius namadicus.

Additional centres for cattle domestication in the subcontinent are possible. The South Indian Neolithic features distinctive ashmounds that are thought to have been produced by the burning of cattle dung (Misra et al. 2001). These have been argued as representing sites of cattle pens that may have served as enclosures for capture and taming of aurochs 5000 years ago (Allchin & Allchin 1974). That these may have given rise to a separate strain of zebu is (tentatively) indicated by early representations that seem to depict cattle with longer horns and more delicate limbs in comparison to those represented in early seals from Baluchistan. More persuasively, finds of large Bos bones suggest the survival of wild cattle populations into the Neolithic in South India and the Ganges region further East (reviewed in Fuller 2006). Recruitment of wild oxen via crossbreeding, or less commonly by capture, in different regions of the subcontinent is thus eminently plausible. Recently, mitochondrial sequence diversity levels within B. indicus has been described widely through Asia and strongly suggest that highest sequence diversity and therefore domestic origins lie within the Indian subcontinent but that these may well not be restricted to the primary Baluchistan region (Chen et al. 2010).

Our model suggests admixture between the continental groups. This is not surprising for a domesticate that would have been a passenger or subject of human trade and migration. This mirrors earlier work that shows traces of African genes in European B. taurus and vice versa (Cymbron et al. 1999; Loftus et al. 1999) and ancestral exchange between Near Eastern and Indian breeds (Loftus et al. 1999; Kumar et al. 2003). For example, a huge secondary input of B. indicus genes into Africa has been described, probably reflecting an ancient Indian Ocean trade corridor stretching back over three millennia (Hanotte et al. 2002).

One issue with the analysis we present here is that many of the loci chosen for resequencing have importance in the immune response and therefore may have been subject to natural selection, which may have skewed the SFS. We use only synonymous and non-coding SFS in our analysis but a possibility remains that skew may persist because of linkage disequilibrium with adaptive sequence variants. However, the high frequency bump in our B. indicus SFS that drives the strong conclusion of majority wild admixture in Indian cattle ancestry is a feature that remains even when the three genes (TRIF, TLR4, ART4) showing highest linkage disequilibrium are removed from the analysis. Also, a skew because of selective effects should manifest in both B. indicus and B. taurus and our strongest conclusion is of divergent domestication histories between the two taxa. Finally, it should be noted that reasonable modelling inference has been achieved in human populations using sequence data with a strong bias towards immunologically important loci, although of course this does not guarantee that such will always be the case (Akey et al. 2004).

In sum, we have constructed a model of bovine population history based on SFS from SNPs sampled from 37 000 bp resequenced in African, European and Indian cattle. This model has several surprising departures from a simple domestication narrative. Bos taurus history involves a severe population bottleneck that seems to predate domestication and which may be a result of glacial habitat restriction. Bos indicus population history contrasts with this, showing no contemporaneous bottleneck, perhaps because of a more benign environment during the glacial maximum but does allow for a later, probably domestication influenced, population constriction. Most strikingly, indicine cattle have had a more complex process of sampling from the wild with a prediction of a substantial secondary admixture from a parallel wild ox population, an assertion that seems archaeologically plausible.

Acknowledgements

This material is based on work supported by the Science Foundation Ireland under Grant No. 02-IN.1-B256. EH-S was a receipt of a EU Marie Curie short term fellowship in Trinity College Dublin, a Genetime training site. A.R. Freeman and D.J. Lynn assisted in project planning.

Footnotes

The first two authors contributed equally to the study.

One contribution of 18 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Genetics and the causes of evolution: 150 years of progress since Darwin’.

References

- Achilli A., et al. 2008Mitochondrial genomes of extinct aurochs survive in domestic cattle. Curr. Biol. 18, R157–R158 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achilli A., et al. 2009The multifaceted origin of taurine cattle reflected by the mitochondrial genome. PLoS ONE 4, e5753 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005753) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey J. M., Eberle M. A., Rieder M. J., Carlson C. S., Shriver M. D., Nickerson D. A., Kruglyak L.2004Population history and natural selection shape patterns of genetic variation in 132 genes. PLoS Biol 2, e286 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020286) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allchin F. R., Allchin B.1974Some new thoughts on Indian cattle. In South Asian archaeology (eds Van Lohuizen-De Leeuw J. E., Ubaghs J. N.). Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill [Google Scholar]

- Baig M., Beja-Pereira A., Mohammad R., Kulkarni K., Farah S., Luikart G.2005Phylogeography and origin of Indian domestic cattle. Curr. Sci. 89, 38–40 [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D. G., Machugh D. E., Cunningham P., Loftus R. T.1996Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5131–5135 (doi:10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C. D., Wakeley J., Sawyer S., Hartl D. L.2001Directional selection and the site-frequency spectrum. Genetics 159, 1779–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., et al. 2010Zebu cattle are an exclusive legacy of the South Asia Neolithic. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1–6 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msp213) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cymbron T., Loftus R. T., Malheiro M. I., Bradley D. G.1999Mitochondrial sequence variation suggests an African influence in Portuguese cattle. Proc. Biol. Sci. 266, 597–603 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. J., et al. 2007Mitochondrial DNA analysis shows a near Eastern Neolithic origin for domestic cattle and no indication of domestication of European aurochs. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274, 1377–1385 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B., Green P.1998Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8, 186–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B., Hillier L., Wendl M. C., Green P.1998Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 8, 175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay E. K., et al. 2007Bayesian inference of population expansions in domestic bovines. Biol. Lett. 3, 449–452 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0146) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A. R., Lynn D. J., Murray C., Bradley D. G.2008Detecting the effects of selection at the population level in six bovine immune genes. BMC Genet. 9, 62 (doi:10.1186/1471-2156-9-62) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. Q.2006Agricultural origins and frontiers in South Asia: a working synthesis. J. World Prehist. 20, 1–86 (doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9006-8) [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R. A., et al. 2009Genome-wide survey of SNP variation uncovers the genetic structure of cattle breeds. Science 324, 528–532 (doi:10.1126/science.1167936) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M. E., Hayes B. J.2009Mapping genes for complex traits in domestic animals and their use in breeding programmes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 381–391 (doi:10.1038/nrg2575) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D., Abajian C., Green P.1998Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutenkunst R. N., Hernandez R. D., Williamson S. H., Bustamante C. D.2009Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet 5, e1000 695 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000695) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanotte O., Bradley D. G., Ochieng J. W., Verjee Y., Hill E. W., Rege J. E.2002African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations. Science 296, 336–339 (doi:10.1126/science.1069878) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. Y., Larson G., Edwards C. J., Heupink T. H., Lakin K. E., Holland P. W., Shapiro B.2008Correlating Bayesian date estimates with climatic events and domestication using a bovine case study. Biol. Lett. 4, 370–374 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. R.2000A new statistic for detecting genetic differentiation. Genetics 155, 2011–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Subramanian S.2002Mutation rates in mammalian genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 803–808 (doi:10.1073/pnas.022629899) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Freeman A. R., Loftus R. T., Gaillard C., Fuller D. Q., Bradley D. G.2003Admixture analysis of South Asian cattle. Heredity 91, 43–50 (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800277) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S. J., Liu Y. P., Liu Y. X., Li X. W., Yao Y. G.2006Genetic diversity and origin of Chinese cattle revealed by mtDNA D-loop sequence variation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 38, 146–154 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.06.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenstra J. A., Bradley D. G.1999Systematics and phylogeny of cattle. In The genetics of cattle (eds Fries R., Ruvinsky A.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International [Google Scholar]

- Lewin H. A.2009Genetics. It's a bull's market. Science 324, 478–479 (doi:10.1126/science.1173880) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus R. T., Machugh D. E., Bradley D. G., Sharp P. M., Cunningham P.1994Evidence for two independent domestications of cattle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2757–2761 (doi:10.1073/pnas.91.7.2757) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus R. T., Ertugrul O., Harba A. H., El-Barody M. A., Machugh D. E., Park S. D., Bradley D. G.1999A microsatellite survey of cattle from a centre of origin: the near East. Mol. Ecol. 8, 2015–2022 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00805.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceachern S., Hayes B., Mcewan J., Goddard M.2009An examination of positive selection and changing effective population size in Angus and Holstein cattle populations (Bos taurus) using a high density SNP genotyping platform and the contribution of ancient polymorphism to genomic diversity in domestic cattle. BMC Genomics 10, 181 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-181) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machugh D. E., Bradley D. G.2001Livestock genetic origins: goats buck the trend. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5382–5384 (doi:10.1073/pnas.111163198) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee D. A., Mannen H., Bradley D. G.2007Duality in Bos indicus mitochondrial DNA diversity: support for geographical complexity in zebu domestication. In The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia. Inter-disciplinary studies in archaeology, biological anthropology, linguistics and genetics (eds Petraglia M. D., Allchin B.). Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Marth G., et al. 2003Sequence variations in the public human genome data reflect a bottlenecked population history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 376–381 (doi:10.1073/pnas.222673099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marth G. T., Czabarka E., Murvai J., Sherry S. T.2004The allele frequency spectrum in genome-wide human variation data reveals signals of differential demographic history in three large world populations. Genetics 166, 351–372 (doi:10.1534/genetics.166.1.351) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadow R.1987Faunal exploitation patterns in eastern Iran and Baluchistan: a review of recent investigations. In Oreintalia Iosephi Tucci Memoriae Dicata (eds Gnoli G., Lanciotti L.), Rome, Italy: Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estermo Oreinte [Google Scholar]

- Misra V. D., Pal J. N., Gupta M. C.2001Excavation at Tokwa: a Neolithic-Chalcolithic settlement. Pragdhara 11, 59–72 [Google Scholar]

- Ostrander E. A., Wayne R. K.2005The canine genome. Genome Res. 15, 1706–1716 (doi:10.1101/gr.3736605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J., Sánchez-DelBarrio J. C., Messeguer X., Rozas R.2003DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19, 2496–2497 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M., Scheet P.2005Accounting for decay of linkage disequilibrium in haplotype inference and missing-data imputation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 449–462 (doi:10.1086/428594) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock F., Edwards C. J., Bollongino R., Finlay E. K., Burger J., Bradley D. G.2009Cytochrome b sequences of ancient cattle and wild ox support phylogenetic complexity in the ancient and modern bovine populations. Anim. Genet. 40, 694–700 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01905.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy C. S., Machugh D. E., Bailey J. F., Magee D. A., Loftus R. T., Cunningham P., Chamberlain A. T., Sykes B. C., Bradley D. G.2001Genetic evidence for near-Eastern origins of European cattle. Nature 410, 1088–1091 (doi:10.1038/35074088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Baren M. J., Heutink P.2004The PCR suite. Bioinformatics 20, 591–593 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila C., Seddon J., Ellegren H.2005Genes of domestic mammals augmented by backcrossing with wild ancestors. Trends Genet. 21, 214–218 (doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendorf F., Schild R.1994Are the early Holocene cattle in the Eastern Sahara domestic or wild? Evol. Anthropol. 3, 118–128 (doi:10.1002/evan.1360030406) [Google Scholar]