Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether performance in Trail Making Test (TMT) predicts mobility impairment and mortality in older persons.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study.

SETTING

Community-dwelling older persons enrolled in the InCHIANTI Study.

PARTICIPANTS

865 participants ≥65 years, free of major cognitive impairment (MMSE >21), with complete baseline data on Trail Making Test (TMT) performance. Of these, 583 performed the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) both at baseline and after 6-years. Of the initial 865 participants, 222 died during 9-years of follow-up.

MEASUREMENTS

The Trail Making Test (TMT-A, TMT-B, TMT-B minus A) and the Short Physical Performance Battery for the assessment of lower extremity function were administered at baseline and at 6-years follow-up. Impaired mobility was defined as an SPPB <10. Vital status was ascertained over a 9-year follow-up.

RESULTS

Of 679 participants free of ADL disability and with SPPB ≥10 at baseline, 53 (11.0 %) developed impaired mobility (SPPB score < 10) during the follow-up. Participants in the lowest quartile of TMT-performance at baseline were significantly more likely to develop a SPPB score < 10 during the 6 years follow-up compared to those in the highest quartile. After adjusting for potential confounders this prognostic effect was substantially maintained. Also, worse performance on the TMT was associated with significantly greater decline of SPPB score over the 6-year follow- up, after adjusting for age, sex and, baseline SPPB score. During a nine-years follow-up, 222 participants (25.7 %) died. The proportion of participants who died was higher in the lowest performance quartile compared with the best performance quartile of TMT score, for TMT-A; TMT-B; and TMT B-A scores.

CONCLUSION

Performance in the Trail Making Test is a strong, independent predictor of mobility impairment, accelerated decline in lower extremity function and mortality among older adults living in the community. The Trail Making Test is a useful addition to geriatric assessment.

Keywords: Trail Making Test, neuropsychological tests, physical impairment, mortality

Introduction

Executive function “involves the ability to think abstractly and to plan, initiate, sequence, monitor, and stop complex behaviour.”(1) There is emerging evidence that executive function is the critical “cognitive” component of mobility, which is particularly important when facing real-life mobility tasks that are complex and challenging.(2, 3) Thus, it has been suggested that the assessment of executive function should routinely introduced in the assessment of older persons that experience mobility problems. (4) The Trail Making Test, an easy and quickly administered neuropsychological test, assesses cognitive abilities such as visual-conceptual and visual-motor tracking, sustained attention, task alternation abilities.(5-7) Research have suggested that performance in Trail Making Test (TMT) conveys information on executive function domain that is relevant to mobility and autonomy in Activities of Daily Living. ( 8-11) Whether poor TMT performance is a risk factor for the development of mobility impairment is unknown.

It is generally known that poor cognitive function is associated with shorter life expectancy. (12-14) In older persons with overt cognitive impairment, decrements in Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) are related to consistent reduction in survival probability. (15,16) In contrast, the relation between mild cognitive dysfunction and survival is less well established. Since executive function impairment occurs early in the development of cognitive decline, it would be useful to know whether performance in neuropsychological tests may already capture the effect of poor cognition and mortality.

We examined the relationship between TMT score at enrollment and the development of mobility disability and mortality over, respectively, a 6- and 9-year follow up among participants in the InCHIANTI study, a representative population-based study of older adults living in the Chianti region of Tuscany, Italy.

Subjects and Methods

Study sample

The study sample consisted of men and women, aged 65 and older, who participated in the Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in the Chianti Area” (InCHIANTI) study, conducted in two small towns (Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli) of Tuscany, Italy. The rationale, design, and data collection have been described elsewhere.(17) Briefly, randomly selected subjects from the population registries received extensive information on the study and those who agreed to be enrolled signed an informed participation consent. The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee. Participants responded to a structured home interview and underwent a full medical and functional examination. The Mini-Mental Status Examination, the Trail Making Test and the Short Physical Performance Battery were administered to all subjects at baseline and at 3-year and 6-year follow-up. For the purpose of this analysis we excluded participants (74 subjects, 8.2 %) with overt cognitive impairment (MMSE ≤ 21) at baseline. Information on vital status during the follow-up was gathered from the Mortality General Registry maintained by the Tuscany Region and the death certificates that are deposited immediately after the death at the Registry office of the Municipality of residence. In this study we considered mortality that occurred between 1998, year of the enrolment, and the end of 2007. Of the 865 participants with valid baseline measures of Trail Making Test (TMT) performance, 583 were evaluated with the Summary Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) both at baseline and at the 6-years follow-up. Of 282 persons who were not seen at the 6-year follow-up visit, 148 had died, 13 had moved from the study area and could not be traced, 28 refuse to participate in the follow-up, 93 participated but did not perform the SPPB either because they refused the test or because they had contraindications.

Cognitive measures

The Trail Making Test is administered in two parts (6, 18). Part A is a visual-scanning, timed task where participants are asked to connect with lines 25 circles numbered from 1 to 25 as quickly as possible. The test is terminated after 5 minutes even if not completed. In Part B participants are asked to connect circles containing numbers (from 1 to 13) or letters (from A to L) in an alternate numeric/alphabetical order (i.e. 1-A-2-B-3-C etc.). Errors must be corrected immediately and the sequence re-established. The test is terminated in every case after 10 minutes even if not completed. The TMT A-B score calculated as the difference between TMT-A and TMT-B times is considered a measure of cognitive flexibility relatively independent of manual dexterity. (19, 20)

Physical performance measures

The SPPB includes three simple tests: a 4-m timed walk at self-selected usual pace, rising from chair 5 times without using arms, maintaining balance in three progressively more challenging positions: feet side-by-side, semi-tandem and a full-tandem. For each of these three physical performance tests, participants received a score from 0 to 4, with a value of 0 indicating the inability to complete the test and 4 the highest level of performance. The values were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 12 with higher scores representing better performance. (21) Previous studies have demonstrated that older, nondisabled persons with a low score are at high risk of developing disability (22). The Short Physical Performance Battery score has excellent reliability and is highly sensitive to clinically important change (21-24).

The analyses presented here concerned participants who performed the SPPB both at the enrolment and after 6 years. Mobility impairment was defined as a SPPB score < 10. We evaluated whether in participants without mobility impairment (SPPB>10) at baseline (679 subjects) lower TMT performance was associated with higher risk of developing mobility impairment at follow-up compared with higher TMT performance. In further analyses, change in SPPB was calculated as the difference between SPPB score at the 6-year follow up and at baseline.

Demographic Characteristics and Health Status

Education was assessed at the maximum achieved educational level (years of schooling), based on self report, subjects were classified as current smokers, or not smokers.

Alcohol consumption was measured as average daily intake of alcohol during the previous year using data collected in the context of a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire.

The presence of the following medical conditions was established using standardized criteria that combined information from self-reported history, medical records and, a clinical medical examination: cancer, hypertension, angina pectoris, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, Parkinson disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic bronchitis/emphysema, renal function. Number of diseases (1-10) was used to assess the burden of comorbidity.

The Italian version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to evaluate depressive symptoms. The Snellen letter chart was utilized to assess visual acuity, with corrective lenses permitted using standardized methods.

A standard resting one minute 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed during the technical evaluation session and interpreted by a cardiologist, and the reading protocol included standard criteria for the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.

Motor coordination was evaluated with tests of rapid alternate movements of upper limbs.

In the finger-nose test, the subject was asked to touch the tip of his nose 5 times, as rapidly as possible, with the index finger of the hand. In the finger-tapping test, the subject was invited to rapidly perform the greatest possible number of tapping movements of the index finger on a rigid flat surface, and we reported how many movements he completes in 20 sec.

Statistical analysis

Variables are reported as means (standard deviations) for normally distributed parameters or as percentages. Means were compared using age- and sex-adjusted ANOVA and percentages with age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression models. According to the time employed to perform each part of the Trail Making Test, participants were classified into quartiles. Quartiles for TMT-A were defined as: 21-54 seconds (first quartile), 55-79 seconds (second quartile), 80-121 seconds (third quartile), and time >121 seconds (fourth quartile). Quartiles for TMT-B were defined as: 52-125 seconds (first quartile), 126-198 seconds (second quartile), 199-482 seconds (third quartile), and time >482 seconds (fourth quartile). For both the A and B subtests participants who started but did not completely finish the test were included in the worse quartile and for calculating the difference between A and B they were assigned the longest allowed time. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between Trail Making Test performance and the risk of developing impaired mobility (SPPB <10) after adjusting for age, sex and multiple potential confounders. A recent literature suggests that in longitudinal analyses predicting a dichotomous outcome when outcome occurs in more than 10% of the participants it is desirable to estimate Relative Risks (RRs) directly instead of the OR approximation. For this reason, the analysis predicting impaired mobility was repeated using the “modified Poisson” approach proposed by Zou which directly provides RR. (25, 26)

Linear regression models were used to examine the association between TMT performance and change in SPPB score during the 6-year follow-up after adjusting for confounders including baseline SPPB scores. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the relationship between Trail Making Test performance and mortality. Survival curves were statistically compared using log-rank tests. Proportional hazards assumptions were verified by examining scaled Schoenfeld and Martingale residuals plots. Fully adjusted models were reduced to parsimonious models that only included variables that were significant predictors of the outcome. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) with a significance level set at p <0.05.

Results

At baseline, the mean age of the study sample was 74.1 ± 6.3 years, with 5.7± 3.3 education years and 53.1 % women (Table 1). The average time to complete the Trail A and Trail B were, respectively, 98.9 ± 64.4 and 274.7 ± 183.3 seconds. The average SPPB score was 10.4 ± 2.5. After adjustment for age, participants with baseline SPPB score > 10 and in the highest quartile of Trail A time at baseline (poor TMT-performance) were significantly more likely than subjects in the lowest TMT quartile (good TMT-performance) to have a SPPB score < 10 at 6 years follow-up, compared to the first quartile. This prognostic effect of TMT-A remained statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounders as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at enrolment and at the 6-year follow-up and data on mortality.

| Total (n=865) | Evaluated after 6- years follow- up (n=583) |

Alive after 9- years follow-up (n=643) |

Died at 9-years follow-up (n=222) |

P# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean±S.D.) | 74.1 ± 6.3 | 78.9 ± 5.5 | 72.5 ± 5.2 | 78.7 ± 7.0 | <.0001 |

| Sex female (%) | 53.1 | 54.4 | 56.3 | 43.69 | <.0001 |

| Education (years) 1 (Mean±S.D.) | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 6.0 ± 3.4 | 5.9 ± 3.3 | 5.3 ± 3.2 | 0.8846 |

| Current smokers (%) | 15.61 | 8.6 | 13.4 | 20.7 | <.0001 |

| Summary Physical Performance Battery Score | 10.4 ± 2.5 | 9.1 ± 3.5 | 10.9 ± 1.8 | 8.8 ± 3.4 | <.0001 |

| Alcool Intake (g/day)(Mean±S.D.) | 17.2 ± 16.8 | 14.1 ± 12.0 | 17.2 ± 16.3 | 17.1 ± 18.3 | 0.0724 |

| *Number of diseases (%) | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | <.0001 |

| CES-D Score (Mean±S.D.) | 12.4 ± 8.7 | 13.4 ± 7.4 | 12.0 ± 8.6 | 13.7 ± 8.9 | 0.8029 |

| Trail Making Test Part ‘A’ (Sec) (Mean±S.D.) | 98.9 ± 64.4 | 85.3 ± 48.1 | 88.6 ± 55.5 | 128.8 ± 77.8 | 0.0081 |

| Trail Making Test Part ‘B’ (Sec) (Mean±S.D.) | 274.7 ± 183.3 | 384.8 ± 207.0 | 247.8 ± 174.2 | 352.36 ± 187.01 | 0.0073 |

| Trail Making Test ‘B-A’ (Sec) (Mean±S.D.) | 175.7 ± 146.6 | 268.8 ± 187.1 | 159.2 ± 142.3 | 223.5 ± 148.8 | 0.0329 |

| Mini Mental State Examination score (Mean±S.D.) | 26.0 ± 2.4 | 25.1 ± 4.7 | 26.3 ± 2.3 | 25.2 ± 2.5 | 0.0105 |

| Visual acuity at 3 meters (0/10-11/10) (Mean±S.D.) | 7.6 ± 2.8 | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 6.8 ± 2.9 | 0.5529 |

| Visual acuity near (Snellen 0.04-0.50) (Mean±S.D.) | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | 0.43 ± 0.10 | 0.38 ± 0.12 | 0.0026 |

| Halsted-Reitan Mechanical Tapping Test (Mean±S.D.) | 36.7 ± 10.6 | 49.5 ± 11.3 | 38.1 ± 10.3 | 32.3 ± 10.4 | 0.0007 |

| Coordination (Dysmetria) (%) | 27.1 | 5.7 | 23.2 | 38.3 | 0.0156 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 2.77 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 6.8 | 0.0002 |

Mean (SD) for continuous variables or percentages as noted;

Age-adjusted ANOVA or Logistic Regression Analyis between survivors and died at the 9-year follow-up

Including patients with at least 1 of the following diseases: Cancer, Hypertension, Angina pectoris, Congestive heart failure, Myocardial infarction, Stroke, Parkinson disease, Diabetes mellitus, Chronic bronchitis/emphysema, Chronic kidney disease.

Table 2.

Relationship Between Quartiles of Trail Making Test “Part A” and “Part B” and “Delta TMT” and reduced mobility defined a having a SPPB score less than 10

| Risk of Frailty (SPPB < 9) at 6 years Follow-up (n = 481) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Fully*-adjusted | |||||

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Trail Making Test “A” (Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | <.0001 | p2 for trend | <.0001 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1 | (- - - -) | --- | 1 | (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile2 | 2.7 | (0.9- 3.3) | 0.0946 | 1.9 | (1.0-3.9) | 0.0606 |

| Quartile 3 | 2.8 | (1.5-5.1) | 0.0008 | 3.3 | (1.8-6.3) | 0.0003 |

| Quartile 4 | 5.0 | (2.5-10.1) | <.0001 | 5.4 | (2.5-11.5) | <.0001 |

| Risk of Frailty (SPPB < 9) at 6 years Follow-up (n = 481) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Fully*-adjusted | |||||

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Trail Making Test “B”(Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | 0.0005 | p2 for trend | 0.0005 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1 | (- - - -) | --- | 1 | (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile 2 | 1.4 | (0.7 - 2.6) | 0.2631 | 1.1 | (0.6 - 2.0) | 0.4381 |

| Quartile 3 | 3.1 | (1.7 - 5.6) | 0.0002 | 3.0 | (1.6 - 5.4) | 0.0002 |

| Quartile 4 | 2.4 | (1.2 - 4.6) | 0.0108 | 2.7 | (1.4 - 5.2) | 0.0184 |

| Risk of Frailty (SPPB < 9) at 6 years Follow-up (n =481 ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Fully*-adjusted | |||||

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Delta TMT (Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | 0.0010 | p2 for trend | 0.0059 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1 | (- - - -) | --- | 1 | (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile 2 | 1.5 | (0.8 - 2.7) | 0.1978 | 1.5 | (0.7 - 2.6) | 0.3585 |

| Quartile 3 | 2.5 | (1.4 - 4.6) | 0.0029 | 2.5 | (1.3 - 4.7) | 0.0059 |

| Quartile 4 | 2.5 | (1.3 - 4.8) | 0.0055 | 2.2 | (1.1 - 3.1) | 0.0344 |

Trail Making Test A and B and Delta quartiles 2, 3 and 4 are compared to quartile 1 considered as the reference group.

P for trend was obtained by considering Trail Making Test A and B and Delta quartile level as an ordinal variable

Parsimonious Model adjusted for age, sex, depression and dysmetria. Obtained by Backward Selection Method from an Initial Models also adjusted for age, sex, Mini Mental State Examination, education, current smoking, atrial fibrillation, visual acuity, alcool intake, number of diseases, upper estremities coordination,depression and dysmetria.

We observed similar results when the association between Trail B quartile time at baseline and SPPB score at a 6- year follow-up was analyzed. After adjustment for age, participants in the highest quartiles of time to perform Trail B at baseline were more likely than subjects in the lowest quartile to have a SPPB score< 10 at follow-up. After adjusting for potential confounders the prognostic effect of TMT-B was substantially maintained. When the same analysis was repeated using the Delta-TMT, the results were substantially comparable (Table 2).

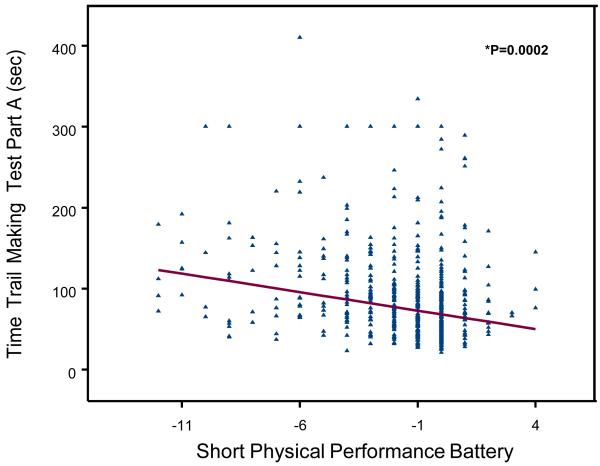

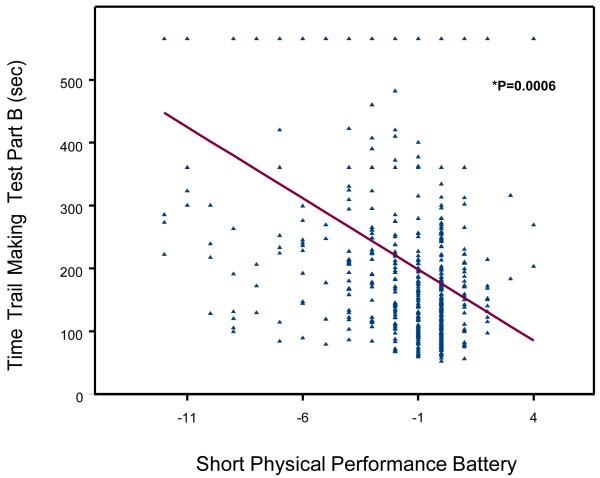

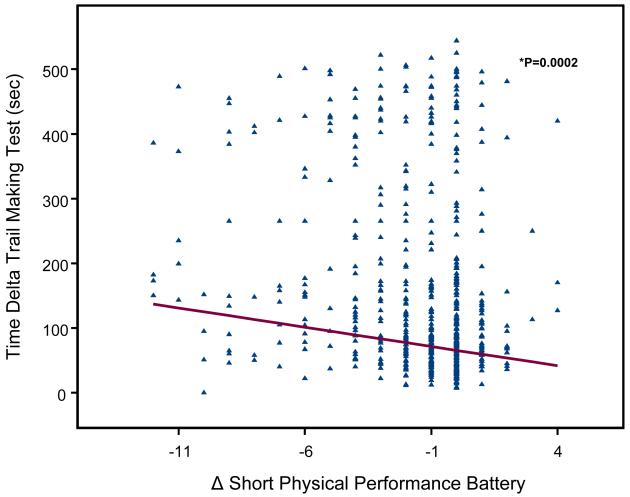

A scatterplot of the relationship between TMT-performance (Trail A, Trail B, Delta-TMT) and age- and sex- adjusted changes in SPPB score between baseline and the 6-year follow-up are shown in Figure 1, 2 and 3. Change in SPPB score between baseline and 6-year follow-up ranged from −12 to 4, with a mean change of −1.6 ± 2.7. Lower extremity performance declined during the follow-up in 325 (56.2%) participants; in particular, SPPB scores of 142 (24.57%) participants declined by 3 or more points (a decline of at least 2 points more than the median change of −1). SPPB scores did not change between baseline and follow-up for 194 (33.3%) participants and 65 (11.1%) participants improved their performance scores.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Poor TMT-A and TMT-B performance were significantly associated with steeper decline of SPPB at 6-year follow-up after adjusting for age, sex, and baseline SPPB score (respectively: Part A, beta =−0.007, SE 0.001, P = 0.0002; Part B, beta =−0.003, SE 0.0006, P = <.0001). Similar results were observed with Delta-TMT (beta =−0.003, SE 0.0008, P = 0.0002).

Finally we examined the effect of TMT-performance (Trail A, Trail B and Delta-TMT) on the risk of death. Of the initial 865 participants, 222 (25.7 %) died during the 9-years follow-up. Participants who died were older, had a lower education level, had worse performance in the Trail Making Test and lower SPPB scores compared to those who survived.

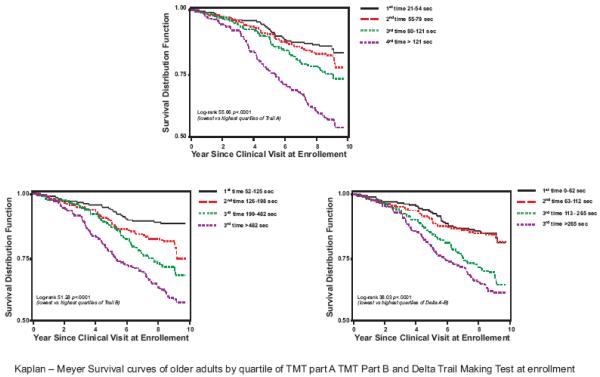

Mortality was progressively and significantly higher from the best to the worse quartile of TMT-A and TMT-B and also by quartile of delta-TMT (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

In Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age and sex, participants in the lowest quartile of Trail Making Test A at enrollment had significantly lower mortality compared to those in the highest quartile (Hazards Ratio 1.8, 95%; CI 1.2-2.8; p=0.005) (Table 3). Results remained similar even in a parsimonious model that only included independent variables significantly associated with the outcome, namely age, sex, depression and dysmetria of the clinical exam. When we analysed Trails B, the highest quartile of TMT-B performance identified participants at greater risk of mortality in the model adjusted for age and sex (Hazards Ratio 2.4, 95%; CI 1.5-3.7; p=0.0003). The significant prognostic effect of TMT-B was confirmed adjusting for confounders, age, sex, mini mental examination, education, current smoking, depression, atrial fibrillation, visual acuity, alcool intake, number of diseases, upper estremities coordination, dysmetria. Similar results were obtained with Delta-TMT after adjusted for age, sex (Hazards Ratio 1.6, 95%; CI 1.1-2.4; p=0.0229) and after obtaining a parsimonious model (Hazards Ratio 1.6, 95%; CI 1.0-2.6; p=0.047).

Table 3.

Relationship between TMT part “A” ,“B”, Delta-TMT and all cause mortality over 9-year follow-up

| Age-adjusted HR 95% C.I. |

P | Fully3-adjusted HR 95% C.I. |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trail Making Test “A” (Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | 0.0012 | p2 for trend | 0.1458 |

| Quartile 1 | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile 2 | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 0.7029 | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) | 0.3825 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.4 (0.9-2.1) | 0.1676 | 1.6 (1.0-2.6) | 0.0594 |

| Quartile 4 | 1.8 (1.2-2.8) | 0.005 | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 0.1841 |

| Trail Making Test “B” (Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | 0.0005 | p2 for trend | 0.0026 |

| Quartile 1 | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile 2 | 1.8 (1.1-2.9) | 0.0215 | 1.8 (1.0-3.0) | 0.0436 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.8 (1.1-2.9) | 0.0155 | 1.9 ( 1.2-3.2) | 0.0116 |

| Quartile 4 | 2.4 (1.5-3.7) | 0.0003 | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) | 0.0019 |

| Delta Trail Making Test (Sec) 1 | p2 for trend | 0.0052 | p2 for trend | 0.0209 |

| Quartile 1 | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- | 1.0 (- - - -) | --- |

| Quartile 2 | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 0.9992 | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | 0.9775 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 0.0606 | 1.5 (0.9-2.4) | 0.0866 |

| Quartile 4 | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 0.0229 | 1.6 (1.0-2.6) | 0.047 |

Trail Making Test A and B and Delta quartiles 2, 3 and 4 are compared to quartile 1 considered as the reference group.

P for trend was obtained by considering Trail Making Test A and B and Delta quartile level as an ordinal variable

Parsimonious Model adjusted for age, sex, mini mental, current smoking, number of diseases. Obtained by Backward Selection Method from an Initial Models also adjusted for age, sex, mini mental examination, education, current smoking, depression, atrial fibrillation, visual acuity, alcool intake, number of diseases, upper estremities coordination, dysmetria.

Discussion

This study examined the association of performance in a neuropsychological test assessing executive function with the risk of developing mobility impairment and dying, respectively, over 6-years and 9-years of follow-up. We found that older community-dwelling adults with poor performance in the Trail Making Test (TMT-A, TMT-B and Delta-TMT) are at higher risk of developing mobility impairment, experience accelerated decline of lower extremity performance and have higher risk of dying over the follow-up.

Our findings are consistent with observations in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF), that assessed 9704 community-dwelling women older than 65 years, and found that impairment on Trails-B was a strong risk factor for the development of incident ADL and IADL dependence, worsening of ADL or IADL disability, and mortality over a 6- year follow-up.(27) In a previous cross-sectional analysis also performed in the InCHIANTI Study it was demonstrated that Delta Trail B-A, used as indicator of executive function, was strongly correlated with physical performance and, particularly, with tasks of lower extremity function that require high attentional demand. (2)

The present analysis confirms previous cross-sectional findings and adds information about the predictive value of the TMT on physical function and mortality. Relatively little attention has been given to the study of the specific cognitive correlates of functional outcomes. The majority of neuropsychological tests are not designed to predict how individuals are likely to function in real-life setting, and live independently (28). It has been suggested that some cognitive domains may be more relevant to mobility than others. Measures of executive control function are relatively strong correlates of functional capacities.(29,30)

Some studies investigated the brain regions engaged by TMT through functional neuroimaging demonstrating that TMT performance is related to frontal regions activity. In particular, clinical-anatomic and functional neuroimaging data point to the critical role of prefrontal cortex in the regulation of cognitive flexibility, concentration, attention, planning and intention. (31-34).

In addition, there is also evidence that the brain-behavior correlations for the TMT are multifaceted and not restricted to the frontal lobe (31).

It is interesting to note that cortical areas whose function has been correlated with the TMT performance are involved in movement control, especially in non-usual responses or adaptative motor strategies to environmental challenges. In agreement with other studies, our results suggest that integrity of executive function is an essential aspect to perform properly in tasks of lower extremity function. Gait speed, chair-stand test, standing balance in progressively more challenging positions require psychomotor integration and visuomotor speed, abilities assessed through administration of Trail Making Test. The strong association that seems to be between neuropsychological tests of executive function and physical performance tasks may account for disability in ADL and IADL pointed out in persons with executive dysfunction. In other words, it may be that physical impairment related to executive dysfunction explains, in part, and underlies functional impairment in activities of daily living.

Schneider and Lichtenberg examined the performance in two executive ability measures (Trail Making Test B and Animal Naming) of 68 urban Black older adults with majority of females (78 %) from the Stress and Success in Aging through Good Health and Executive Ability (SAGE) database and found a significant association between executive ability and SPPB, indicator of preclinical disability. (35) Our findings confirm this association over a time of 6-years follow-up in a different population group, with 53.1 % of females.

It is generally accepted that TMT-A and TMT-B are equivalent in their demands for visual search, simple sequencing and psychomotor functioning. TMT-B requires greater cognitive flexibility than TMT-A, which can be selectively estimated as Delta TMT. Consequently, Trail-B and Delta-TMT are usually utilized in clinical research setting. Surprisingly, in our finding both subtest have predictive value on outcomes such as physical impairment (SPPB < 10) or physical worsening (change in SPPB), suggesting that also TMT-A may supply relevant preclinical information.

We considered, furthermore, the possible usefulness of the Trail Making Test in predicting adverse outcome such as mortality. It is well established the association of MMSE scores with survival probability, especially in case of dementia. MMSE is a valid, routinely utilized instrument for screening of cognitive function. (36) A potential problem with tests of global cognitive function such as the MMSE is their focus on cortical functions such as memory, rather than on subcortical dysfunction such as executive function. This may make the MMSE insensitive for the detection of early cerebral damage.

Existing works suggest that skills dependent on the integrity of frontal networks may be particular useful in predicting survival. In Alzheimer’s disease prefrontal hypometabolism on PET has been associated with impaired visuospatial and executive skills and with disease presentation characterized by reduced survival. An interesting work reported that after evaluation of the predictive value of a range of neuropsychological abilities measured at diagnosis in patients with incident AD, the index of verbal fluency was the only significant neuropsychological predictor of mortality. (37) Whether variations in neuropsychological performance among elderly not necessarily suffering from dementia have any survival prognostic significance is not clear and contrasting results are reported. That is why it is interesting and challenging to individuate neuropsychological instruments with predictive value with respect to survival. Nishiwaki et al. assessed the predictive validity of the Clock-Drawing Test (CDT) with regard to mortality was assessed and demonstrated that a worse CDT score was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality and mortality from cerebrovascular and respiratory diseases. (38) Our neuropsychological findings confirm that a poor performance in executive skills is associated with higher risk of death, conversely a successful performance is associated to a major survival. In conclusion, a poor performance in TMT is significantly related to adverse outcomes as a major risk of mobility disability and death.

The present data contribute to growing the literature suggesting that age-related decline in executive function is not without consequences for the health of older individuals and executive screening should routinely introduced in the geriatric assessment. (39)

This study has some limitations: executive function in the InCHIANTI study was assessed solely with the TMT, but there are other measures of executive control that in conjunction with the TMT would have provided a more comprehensive evaluation of executive control functions. In addition for InCHIANTI participants neurodiagnostic images are not available and it is not possible to study neuroimaging correlates of these findings, in particular cerebral white matter lesions (LWMs), that are often associated with executive impairment.(40) Even if common in pathological states, executive dysfunction may occur even when dementia is not thought be present. In particular, executive dysfunction in older persons, if not associated with other evident cognitive deficits, often is only perceived by intuition but the complexity of definition and measurement may hinder its aware recognition. Nevertheless its detection is critical to the patient’s mobility, independence, safety and life expectancy. Better integration of cognitive and functional assessment would offer greater clinical utility.

In conclusion, performance in the Trail Making Test is a strong, independent predictor of mobility impairment, accelerated decline in lower extremity function and mortality among older adults living in the community. The Trail Making Test is a useful addition to geriatric assessment.

Acknowledgements

The InCHIANTI study baseline (1998-2000) was supported as a “targeted project” (ICS110.1/RF97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health and in part by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts: 263 MD 9164 and 263 MD 821336); the InCHIANTI Follow-up 1 (2001-2003) was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts: N.1-AG-1-1 and N.1-AG-1-2111); the InCHIANTI Follow-ups 2 and 3 studies (2004-2010) were financed by the U.S. National Institute on Aging ( Contract: N01-AG-5-0002);supported in part by the Intramural research program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. fourth edition. American Psychiatric Association; test revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ble A, Volpato S, Zuliani G, Guralnik JM, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Bartali B, Maraldi C, Fellin R, Ferrucci L. Executive function correlates with walking speed in older persons: the InCHIANTI Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Mar;53(3):410–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppin AK, Shumway-Cook A, Saczynski JS, Patel KV, Ble A, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM. Association of executive function and performance of dual-task physical tests among older adults: analyses from the InChianti study. Age Ageing. 2006 Nov;35:619–24. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy GJ, Smyth CA. Screening Older Adults for Executive Dysfunction. Am J Nurs. 2008 Dec;108(12):62–71. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000341886.15318.20. quiz 71-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manual of Directions and Scoring. War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; Washington, DC: 1994. Army Individual Test Battery. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reitan RM. Trail Making Test: Manual for Administration and Scoring. Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory; Tuscon, AZ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson MC, Fried LP, Xue QL, bandeen-Roche K, Zeger SL, Brandt J. Association between executive attention and physical functional performance in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1999;54 B:S262–70. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.5.s262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grigsby J, Kaye K, Baxter J, Shetterly SM, Hamman RF. Executive cognitive abilities and functional status among community-dwelling older persons in the San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 May;46(5):590–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell-McGinty S, Podell K, Frazen M, et al. Standard measures of executive function in predicting instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:828–34. doi: 10.1002/gps.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahn-Weiner DA, Malloy PF, Boyle PA, Marran M, Salloway S. Prediction of functional status from neuropsychological tests in community-dwelling elderly individuals. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000 May;14(2):187–95. doi: 10.1076/1385-4046(200005)14:2;1-Z;FT187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelman HR, Thomas C, Kennedy GJ, Cheng J. Cognitive impairment and mortality in older community residents. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1255–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldereschi MD, Di Carlo A, Maggi S, Grigoletto F, Scarlato G, Amaducci L, Inzitari D. Dementia is major predictor of death among the Italian elderly. Neurology. 1999;52:709. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Small BJ, Bäckman L. Cognitive correlates of mortality: evidence from a population-based sample of very old adults. Psychol Aging. 1997 Jun;12(2):309–13. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettigrew LC, Thomas N, Howard VJ, Veltkamp R, Toole JF. Low mini-mental status predicts mortality in asymptomatic carotid arterial stenosis. Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study investigators. Neurology. 2000 Jul 12;55(1):30–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carcaillon L, Pérès K, Péré JJ, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF. Fast cognitive decline at the time of dementia diagnosis: a major prognostic factor for survival in the community. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(6):439–45. doi: 10.1159/000102017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenut E, Di Iorio A, Macchi C, Harris TB, Guralnik JM. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drane DL, Yuspel RL, Huthwaite MA. Demographic characteristics and normative observations for derived Trail Making Test Indices. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2002;15:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigan JD, Hinkeldey NS. Relationship between Pars A and B of Trail Making Test. J Clin Psychol. 1987;43:402–408. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198707)43:4<402::aid-jclp2270430411>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitan RM. Validiy of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;81:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994 Mar;49(2):M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostir GV, Volpato S, Fried LP, Chaves P, Guralnik Reliability and sensitivity to change assessed for a summary measure of lower body function: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):916–921. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, Leveille SG, Markides KS, Ostir GV, Studenski S, Berkman LF, Wallace RB. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000 Apr;55(4):M221–31. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner P. Estimating the Relative Risk in Cohort Studies and Clinical Trials of Common Outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JK, Lui LY, Yaffe K. Executive function, more than global cognition, predicts functional decline and mortality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 October;62(10):1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sbordone RJ. Limitations of neuropsychological testing to predict the cognitive and behvioral functioning of persons with brain injury in real-world settings. Neurorehabilitation. 2001;16(4):199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royall DR, Lauterbach EC, Kaufer D, Malloy P, Coburn KL, Black KJ. The Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association The cognitive Correlates of Functional Status: A Review From the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric. Association J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007 Summer 3;19 doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahn-Weiner DA, Boyle PA, Malloy PF. Test of executive function predict instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling older individuals. Appl Neuropsychol. 2002;9(3):187–91. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0903_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zakzanis KK, Mraz R, Graham SJ. An fMRI study of the Trail Making Test. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(13):1878–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.03.013. Epub 2005 Apr 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Moll FT, Bramati IE, Andreiuolo PA. The cerebral correlates of set- shifting: an fMRI study of the trail making test. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002 Dec;60(4):900–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000600002. Epub 2003 Jan 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julene K. Johnson, Brent A. Vogt, Ronald Kim, Carl W. Cotman, and Elizabeth Head Isolated Excutive Impairment and Associated Frontal Neuropathology. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):360–367. doi: 10.1159/000078183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez JA, Emory E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006 Mar;16(1):17–42. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider BC, Lichtenberg PA. Executive ability and physical performance in urban Black older adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2008;23:59–601. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. No abstract available. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cosentino S, Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Stern Y. Verbal fluency predicts mortality in Alzheimer disease. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006 Sep;19(3):123–9. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000213912.87642.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishiwaki Y, Breeze E, Smeeth L, Bulpitt CJ, Peters R, Fletcher AE. Validity of the Clock-Drawing Test as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Oct 15;160(8):797–807. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royall DR, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ. An empiric approach to level of care determinations: the importance of executive measures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005 Aug;60(8):1059–64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuo HK, Lipsitz LA. Cerebral white matter changes and geriatric syndromes: is there a link? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004 Aug;59(8):818–26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.8.m818. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]