Abstract

Background

The presence and severity of the chronic pain syndrome, fibromyalgia (FM), is associated with unresolved stress and emotional regulation difficulties. Written emotional disclosure is intended to reduce stress and may improve health of people with FM.

Purpose

This study tested the effects of at-home, written emotional disclosure about stressful experiences on the health of people with FM and used multiple follow-ups to track the time course of effects of disclosure.

Methods

Adults with FM (intent-to-treat: n = 83; completers: n = 72) were randomized to write for 4 days at home about either stressful experiences (disclosure group) or neutral time management (control group). Group differences in immediate mood effects and changes in health from baseline to 1-month and 3-month follow-ups were examined.

Results

Written disclosure led to an immediate increase in negative mood, which did not attenuate across the 4 writing days. Repeated-measures analyses from baseline to each follow-up point were conducted on both intent-to-treat and completer samples, which showed similar outcomes. At 1-month, disclosure led to few health benefits, but control writing led to less negative affect and more perceived support than did disclosure. At 3-month follow-up, these negative affect and social support effects disappeared, and written disclosure led to a greater reduction in global impact, poor sleep, health care utilization, and (marginally) physical disability than did control writing. Interpretation of these apparent benefits needs to be made cautiously, however, because the disclosure group had somewhat poorer health than controls at baseline, and the control group showed some minor worsening over time.

Conclusions

Written emotional disclosure can be conducted at home, and there is tentative evidence that disclosure benefits the health of people with FM. The benefits, however, may be delayed for several months after writing and may be of limited clinical significance.

Keywords: emotional disclosure, expressive writing, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, stress

Several lines of theory and research suggest that the awareness, expression, and processing of negative emotions leads to better mental and physical health. For example, experiential avoidance and emotional processing theories propose that inhibiting or avoiding primary emotions is maladaptive (1, 2). Research on alexithymia (3) and emotional approach coping (4) indicates that emotional awareness is associated with better health. Experimental studies on emotional suppression (5) and emotional regulation (6) also support this view.

Perhaps the best evidence for the benefits of emotional awareness and expression comes from research on written emotional disclosure or expressive writing. In the standard paradigm, participants are randomized to write for 15 to 20 minutes daily for several days about either stressful experiences (disclosure) or non-emotional topics (control), and the groups are compared on health changes from baseline to follow-up to determine disclosure’s effects. Most disclosure studies have been conducted on healthy people. In general, these studies support the benefits of disclosure, showing that disclosure leads to reductions in stress symptoms (7, 8), physical symptoms (9), and health care utilization (10, 11); and to improvements in immune functioning (12, 13) and cognitive performance (14–16). An early meta-analysis indicated a moderate effect size (d = .47) of written disclosure compared with control writing in healthy populations (17).

Recent studies have tested the effects of disclosure in clinical samples, but these results are less consistently positive. Some studies have reported benefits of disclosure for people with rheumatoid arthritis or asthma (18, 19), breast cancer (20), HIV (21), patients undergoing bladder surgery (22), and high utilizers of health care services (23). Other studies report more modest or limited benefits of disclosure, including studies of patients with renal cell carcinoma (24), prostate cancer (25), chronic pelvic pain (26) and rheumatoid arthritis (27). Other disclosure studies have reported no benefits among people with rheumatoid arthritis (28), breast cancer (29), asthma (30), HIV (31), or people who were bereaved (32, 33), in primary care (34, 35) or treatment for smoking (36). A recent meta-analysis of disclosure studies in clinical populations (37) reported a substantially smaller effect (d = .19) than found in healthy samples.

The pattern and timing of the effects of disclosure are somewhat complex and variable across studies. A consistent finding is that disclosure leads to increased negative mood immediately after writing (17). With respect to more distal outcomes, some studies have found positive effects as soon as one month after disclosure (e.g., 8, 10, 14), whereas other studies have found delayed benefits. For example, two studies of people with rheumatoid arthritis found benefits after 3 or 4 months, but not earlier (18, 27), and study of medical students found a positive effect of disclosure on immune responses to the hepatitis B vaccination 4 and 6 months—but not 1 month—after disclosure (13). Similarly, a study of breast cancer patients found improvement in physical symptoms at 3-month follow-up, but a trend for the opposite effect at 1-month follow-up (20). A few disclosure studies have actually found statistically significant negative effects of disclosure on some measures at short-term follow-up. Among college students, disclosure writing led to more fatigue and avoidance after 1 month (10) and to greater homesickness and negative affect after 2 to 3 months (15) than did control writing. In clinical samples, disclosure led to worse symptoms after 5 weeks on a small sample of people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 38) and to more physical symptoms at 6-week follow-up among psychiatric inmates (39). Unfortunately, in three of these studies (10, 38, 39), no additional follow-up assessments were conducted to determine how long these negative effects lasted, or whether they might have been followed by health benefits.

The mechanisms underlying the effects of disclosure, and how these processes might influence the time course of the effects, remain unclear. Theories related to exposure, emotional processing, and cognitive and affective changes in people with PTSD or unresolved stress more generally may help explain the effects of disclosure (40–43). Accessing previously avoided negative memories and emotions in writing allows them to be experienced, thus yielding a temporary increase in these negative emotions. How long these negative mood effects last, however, and at what point positive effects occur probably are a function of many variables, including the frequency, intensity, and duration of exposure; the type of stressor being processed; and the person’s emotional regulation capacities. Exposure therapy for PTSD sometimes results in short-term increases in negative emotions in the early weeks of therapy, before symptom attenuation and stressor resolution eventually occur (44, 45). Similarly, disclosure researchers have suggested that the process of disclosure writing initially removes or lowers normal defenses, which forces the person to face and deal with basic conflicts and fears (15). Thus, it is possible that several days of written emotional disclosure initially leads to some increase in negative emotion and arousal, which may facilitate emotional processing and cognitive reflection. These processes may eventuate in meaningful cognitive assimilation or integration and perhaps interpersonal changes, although this may require several months after writing, while the short-term response may be no change or even temporary worsening.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a clinical syndrome characterized by diffuse muscular pain, discrete tender points at multiple soft-tissue sites, fatigue, physical disability, sleep disturbance, and mood problems. This syndrome affects from 2 to 3% of Americans, primarily women (46), and is diagnosed in 5 to 6% of primary care patients and 20% of rheumatology patients (47, 48). Stressful life events such as childhood abuse, adult abuse and victimization, relationship difficulties, and financial stressors are substantially more common in patients with FM than other chronic pain or medical conditions (49–53), and over half of patients with FM have either PTSD or substantial PTSD symptoms (54, 55). Research suggests that people with FM have, on average, difficulty with emotional regulation. For example, mild mental stress leads to increased pain in people with FM but not in controls (56), and inducing a negative mood leads to greater pain in response to interpersonal stress among FM than among osteoarthritis patients (57). Individuals with FM report emotional suppression (58) and an inability to express themselves (59), and they report greater difficulty identifying their feelings and expressing anger than people with rheumatoid arthritis (60). Notably, greater difficulty understanding and expressing emotion is associated with greater pain and depression in this population (61, 62).

The elevated PTSD and deficits in emotional awareness and expression in FM suggest that the technique of written emotional disclosure may benefit this population. Indeed, in a recent laboratory study of people with FM, Broderick et al. (63) tested the effects of written disclosure compared with a control condition (comprised of neutral writing and no writing patients combined). Compared with the control group, disclosure led to significantly lower pain and fatigue and better psychological well-being after 4 months, although there were no significant effects on other health measures including physical functioning, stiffness, other physical symptoms, or overall health.

Goals of this Study

This study adds to the work of Broderick et al. (63) and to the growing literature on disclosure in chronic pain and other clinical populations in several ways. First, there have been conflicting results of disclosure studies conducted on the same clinical population, such as patients with rheumatoid arthritis (18 vs. 28) or asthma (18 vs. 30). Thus, it is important for another group to test the replicability of the findings of Broderick et al. on another sample of people with FM. Second, whereas Broderick et al. assessed the effects of disclosure at 4 months (and also 10 months), we assessed the immediate mood effects of disclosure in FM as well as the short-term (1-month) and longer-term (3-month) health outcomes, which allowed us to track more closely the time course of disclosure’s effects. We anticipated that disclosure writing would lead to an immediate negative mood (while writing) but also to greater improvement in health from baseline to 3-month follow-up, compared with the change in health of control writers. No hypotheses were made about 1-month effects given the inconsistent findings in the literature. Third, we tested written disclosure in the natural environment (at home) rather than laboratory as done by Broderick et al. (and most other studies) even though there has been some concern that unsupervised writing may reduce the effects of disclosure (28). We did this because we sought to test the ecological validity or effectiveness of written disclosure rather than its laboratory efficacy. Finally, the apparent benefits of written disclosure are sometimes due in part to unexpected worsening of controls (e.g., 7, 15, 64), and many studies fail to test or discuss this. Thus, when group differences occurred, we examined how each group changed over time.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adults diagnosed with FM who were recruited by fliers in rheumatology clinics, announcements at FM support groups, and advertisements in an Arthritis Foundation newsletter. Participants who were included reported having a physician-provided diagnosis of FM based on 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for FM (65). To increase sample generalizability, we had only two exclusion criteria: having an autoimmune rheumatic disease or the inability to read and write English. Recruitment was conducted from February 2000 to May 2001 with follow-up through August 2001.

A total of 86 respondents met criteria and consented to participate, of whom 83 completed baseline measures and were randomized—the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample. Of these 83 participants, 11 (13.3%) dropped without conducting a follow-up assessment (and typically without writing). Thus, 72 participants (86.7% of those randomized) completed the intervention and at least one follow-up assessment (at 1 or 3 months) and constitute the completer sample, on which primary analyses were conducted. The completer sample had 70 women (97.2%) and two men (2.8%), and 67 completers (93.0%) were Caucasian, three (4.2%) were African American, and two (2.8%) were Hispanic. Completers had a mean age of 50.3 years (range from 23 to 72), had been diagnosed with FM for a mean of 5.9 years (range 1 to 20 years), and averaged 2.6 years of college (all had at least a 10th grade education). Most (n = 52, 72.2%) were married or living with a partner, and over half (n = 43, 59.7%) were working.

Procedures

Participants telephoned the investigator, were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria, informed of the study protocol, and invited to participate. The study was described generically (to avoid biasing one experimental group or the other) as designed “to see how writing about different aspects of a person’s life might influence their health and adjustment.” Participants were mailed a consent form, which had been approved by the institutional review board, and a packet of health measures for the baseline assessment.

After the consent and baseline measures were mailed back, the experimenter mailed out the writing packet, which contained instructions for the specific group to which they were randomized. The packet contained 4 writing journals, one for each day, each consisting of instructions, pre-and post-mood rating questionnaires, and several blank sheets of paper for writing. These packets were prepared in advance, numbered with a unique identifier, and randomized (via a random numbers table) separately for each gender into the two experimental groups. The experimenter telephoned the participant, who then opened the packet, informed the experimenter of the group assignment, and silently read the instructions while the experimenter read aloud the instructions. The experimenter was blind to group assignment during all interactions with participants until they opened their writing packets. Participants were instructed to write at home for four consecutive days during the next week. On each day of writing, participants completed the mood ratings immediately before and after writing, and participants mailed back the writing packets at the end of the four days. At 1 month and again 3 months after the writing was completed, the health measures were mailed again to participants along with envelopes to return them.

Experimental Groups

Both the disclosure and control groups received parallel sets of written instructions that were designed to create equivalent, credible rationales and to equate the structure of both writing tasks. The first page for both groups provided the same instructions regarding location (i.e., to find a location that is private, where the writer would be alone and not interrupted), timing (i.e., write for at least 15 to 20 minutes for four days in a row), and process (i.e., write freely, do not worry about grammar or language). This was followed by specific group instructions.

Disclosure group

Instructions were taken from those typically used in disclosure studies, with some enhancements designed to help participants identify, process, and resolve a stressor. As a rationale, the written instructions stated that “the goal of this project is to see whether thinking and writing privately for 4 days about stressful events in your life will reduce stress and therefore improve your mood, general health, and adjustment to having fibromyalgia.” Participants were asked to identify a stressful experience that continues to bother them, and they were given additional guidance on how to identify such an experience (e.g., it is difficult to think or talk about, makes them feel anxious or upset when encountering reminders of the experience, or prompts intrusive thoughts). They were instructed to make the memories, images, and emotions as vivid as possible and to write both the facts and their deepest feelings about the experience. In addition, they were instructed “to explore how the stressful experience has affected your fibromyalgia or how you deal with having fibromyalgia, or you might want to explore how the experience has affected your relationships with others.” Participants were encouraged to “work on and resolve one stressful experience at a time, and this means that you might write about the same experience over several days or all four days. However, if you find that you have worked it out or feel better about one experience, you should go on and write about another stressful experience.”

Control group

We used the time management control condition, which is an emotionally neutral condition with face validity as a stress management technique (18, 63). Consistent with the rationale for the disclosure group, the instructions stated that “the goal of this project is to see whether thinking about and writing privately for 4 days about how you manage your time will reduce stress and therefore improve your mood, general health, and adjustment to having fibromyalgia.” Participants were instructed to write about different time periods for each of the four writing days and to write about only their actual behaviors or planned actions rather than their feelings or opinions. These four time periods were, Day 1: what they did with their time over the last week; Day 2: what they did with their time over the last 24 hours; Day 3: what they plan to do with their time over the next 24 hours; Day 4: what they plan to do with their time over the next week.

Measures

Linguistic Analysis of Writings

We analyzed the transcribed writings of all participants using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) software (66). This program counts the number of words that occur in different language categories. We used this as a manipulation check to test whether the two sets of writings differed as expected. We analyzed the total number of words as well as the percentage of total words that were categorized as affect, cognitive, and bodily words, which we expected would be more prevalent in disclosure writings.

Immediate Negative Mood

Immediately before and after writing each day, participants rated how they felt “right now” on an abbreviated version (67) of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Version (PANAS-X; 68). Items were rated on a 0 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal) scale, and we used the anger, guilt, sadness, fear, happiness, and calmness scales. A factor analysis revealed 1 factor (e.g., accounting for 62.5% of the variance), so these 6 scales were averaged for each rating occasion (after reverse scoring happiness and calmness). Higher values indicate more negative mood.

Health outcome measures were completed at baseline and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups. We had one primary health outcome measure (the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FIQ; 69) to assess global health status. The other measures were secondary measures to assess specific health domains. All health measures were scored such that higher scores indicate poorer health or functioning.

Global impact

The FIQ, the primary outcome measure, is the assessment measure most widely used in FM clinical trials (70). The standard 10-item FIQ assesses those components of health that are most affected by FM (physical functioning, work status, depression, anxiety, sleep, pain, stiffness, fatigue, and well being) during the prior week. Scores range from 0 to 100. This measure is sensitive to change following intervention (71). Internal consistency (alpha) for the FIQ in the current sample at baseline was .93.

Pain

This was assessed with the 5-item pain subscale from the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale-2 (AIMS2; 72), a widely-used instrument that measures health status in rheumatic diseases during the past month. Items were worded for fibromyalgia rather than arthritis (e.g., “you had severe pain from your fibromyalgia”) and were rated on a 5-point scale (e.g., 1 = all days, 5 = no days), reverse-scored (so that higher values indicate more pain), and averaged. Baseline alpha for this subscale was .81.

Physical dysfunction

also was assessed with the AIMS2 using 28 items from 6 subscales: mobility level (e.g., “you were in bed or chair for most of the day”), walking and bending (e.g., “you had trouble either bending, lifting, or stooping”), hand and finger function, arm function, self-care tasks, and household tasks. Items were rated on a 5-point scale (e.g., 1 = all days, 5 = no days) and scored so that higher scores indicate greater physical dysfunction. Baseline alpha was .93.

Fatigue

was assessed with the 9-item Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS; 73) which assesses the frequency and severity of fatigue’s interference with physical functioning. Items were rated on a 1 to 7 scale and averaged. Baseline alpha in this sample was .91.

Poor sleep quality

was assessed with a 4-item scale designed to evaluate the previous night’s sleep regarding sleep quality, degree to which sleep was restorative, waking daytime level of alertness, and ability to concentrate (74). Items were rated on a 1 to 7 scale and averaged; higher values indicate poorer sleep. Validation research has shown that poorer self-rated sleep and morning alertness on this questionnaire are associated with a greater likelihood of self-administering a hypnotic medication the next night. Baseline alpha was .85.

Health care utilization

was assessed by having participants recall the number of times during the past month that they visited a physician or other health care specialist for health problems, whether related to their FM or not. The total number of visits was recorded.

Negative affect

was assessed with the 10-item NA subscale from the 60-item PANAS-X (68). Respondents rated the frequency that they experienced each item during the prior 2 weeks on a 1 to 5. Baseline alpha was .89.

Lack of social support

was assessed with the 4-item subscale from the AIMS2 that assesses one’s perceptions that family and friends are available if needed, are sensitive to needs, interested in helping, and understand the effects of the FM. Items were rated regarding how frequently support is available (i.e., 1 = all days, 5 = no days), and averaged; higher values indicate less social support. Baseline alpha was .93.

Approach to Statistical Analyses

Primary analyses were conducted on the completer sample. First, to determine the success of randomization, the disclosure (n = 38) and control (n = 34) groups were compared on demographic and baseline health variables using chi-square tests and analyses of variance (ANOVA). Second, the writings of the completer sample were reviewed to describe the degree of adherence to the experimental instructions and the content of the writings, and the writings were compared on linguistic categories as an additional manipulation check. Third, the effect of writing on immediate mood was tested by calculating post-writing minus pre-writing change scores for the immediate negative mood composite for each writing day and submitting these change scores to a 2 (group) by 4 (day) multivariate repeated-measure ANOVA.

We then examined group effects for each outcome measure at the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups separately using repeated measures ANOVAs, with group as the between-subjects factor and time (baseline and 1-month or 3-month) as the within-subject factor. We hypothesized that there would be significant group × time interactions, reflecting differential group changes from baseline. When these interactions occurred, we examined change within each group from baseline to the follow-up point using paired t-tests to determine which group contributed to the effect. In addition, for each outcome measure, we followed the approach of Broderick et al. (63) and calculated two effect sizes. First, the effect size (ES) was calculated as the difference between the two groups on the change in the outcome measure (follow-up minus baseline) divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD) of the baseline for that measure. Second, we calculated Cohen’s d, which is the same numerator divided by the pooled SD of the change scores (rather than baseline measure). For both effect sizes, positive values indicate more improvement for the disclosure than control group; negative values indicate more improvement for the controls.

Finally, as is typical of clinical trials, some attrition occurred, and 11 of the 83 randomized participants dropped and were lost to follow-up. We compared the 11 dropped participants with the 72 completers on demographic and baseline health variables using t-tests or chi-squares to determine how drop-out may have altered the original sample. We also repeated the prior repeated-measures ANOVAs on 1-month and 3-month outcomes on the ITT sample (N = 83; disclosure n = 45; control, n = 38), to test whether the results held for the entire randomized sample. For these analyses, we replaced missing follow-up values with the participants’ baseline values of the measure.

Results

Comparing Writing Groups at Baseline

The two experimental groups did not differ (all p > .20) on any demographic or medical history variable (age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment status, income, marital status, years diagnosed). Table 1 presents the baseline values of the health measures for both groups, along with F- and p-values from an ANOVA comparing the two groups on the baseline measures. The disclosure group reported worse sleep at baseline than the controls, and marginally (p < .10) worse physical disability; otherwise, the two groups did not differ on baseline values, including the primary measure of global impact (p = .25)

Table 1.

Comparisons of Written Emotional Disclosure and Control Writing on Health Measures at Baseline, 1-Month, and 3-Month Follow-ups (Completer Sample, n = 72)

| Dependent measure Time point |

Disclosure Mean (SD) |

Control Mean (SD) |

F | P | ES | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global impact | ||||||

| Baseline | 58.26 (20.49) | 52.93 (18.11) | 1.34 | .25 | ||

| 1-month | 56.60 (20.42) | 53.31 (17.79) | 0.90 | .34 | .16 | .23 |

| 3-month | 52.70 (20.35) | 53.79 (18.13) | 4.48 | .04 | .34 | .50 |

| Physical Disability | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.07 (0.70) | 1.81 (0.53) | 3.13 | .08 | ||

| 1-month | 2.04 (0.70) | 1.91 (0.57) | 2.35 | .13 | .23 | .37 |

| 3-month | 2.03 (0.72) | 1.90 (0.59) | 3.66 | .06 | .24 | .46 |

| Pain | ||||||

| Baseline | 3.54 (0.95) | 3.19 (0.94) | 2.50 | .12 | ||

| 1-month | 3.32 (0.98) | 3.20 (0.88) | 3.30 | .07 | .28 | .42 |

| 3-month | 3.51 (0.91) | 3.34 (0.87) | 1.93 | .17 | .22 | .34 |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| Baseline | 5.81 (1.04) | 5.62 (1.21) | 0.22 | .48 | ||

| 1-month | 5.49 (1.33) | 5.70 (1.09) | 2.79 | .10 | .31 | .40 |

| 3-month | 5.66 (1.24) | 5.84 (1.11) | 1.55 | .22 | .29 | .30 |

| Poor Sleep | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.62 (1.07) | 3.90 (0.99) | 8.41 | .005 | ||

| 1-month | 4.28 (1.05) | 4.19 (0.83) | 6.15 | .02 | .52 | .58 |

| 3-month | 4.23 (1.06) | 4.22 (0.90) | 7.81 | .007 | .65 | .66 |

| Health care utilization | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.56 (2.13) | 1.44 (1.81) | 0.06 | .81 | ||

| 1-month | 1.66 (1.51) | 2.16 (2.23) | 2.05 | .16 | .30 | .34 |

| 3-month | 1.13 (1.07) | 1.80 (2.21) | 3.94 | .05 | .37 | .47 |

| Negative affect | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.14 (0.69) | 2.28 (0.94) | 0.48 | .49 | ||

| 1-month | 2.12 (0.78) | 1.94 (0.70) | 4.07 | .048 | −.34 | −.48 |

| 3-month | 1.91 (0.71) | 2.14 (0.78) | 0.28 | .60 | .11 | .13 |

| Lack of social support | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.79 (1.10) | 3.13 (1.26) | 1.44 | .23 | ||

| 1-month | 2.84 (1.16) | 2.72 (1.14) | 5.10 | .03 | −.41 | −.53 |

| 3-month | 2.52 (1.05) | 2.84 (1.24) | 0.01 | .91 | −.02 | −.03 |

Note. N for baseline is Disclosure (n = 38) and Control (n = 34). For 1-month follow-up, Disclosure (n = 37) and Control (n = 32). For 3-month follow-up, Disclosure (n = 36) and Control (n = 32).

F and p-values for the baseline rows are from an ANOVA comparing the two groups on baseline values. F and p-values for the 1-month and 3-month rows are from the group × time interaction from a repeated-measures ANOVA that included the baseline and the one follow-up point as within-subject variables. ES is the difference between disclosure group change score (follow-up minus baseline) and control group change score divided by the pooled baseline SD. Cohen’s d is the same numerator divided by the pooled SD of the change scores. Positive values of ES and d indicate greater improvement in the disclosure group than control group. Negative values indicate greater improvement in the control group than disclosure group.

Adherence to Writing and Manipulation Checks

Writings were reviewed for completeness, adherence to instructions, and topics disclosed. All but two of the 72 participants completed all four days of writing; one disclosure and one control participant missed one day each. A review of the content indicated that 29 of the 34 control group participants (85%) wrote only about time management as instructed for all writing days; the other five control group participants wrote primarily about time management, but mentioned something about stress on one (n = 2) or two (n = 3) days. All 38 disclosure group participants wrote only about stressful experiences. The largest percentage of disclosure essays were about participants’ struggles with their own health problems (30.0%). Disclosure essays also frequently discussed conflicts with children or other family members (18.3%) or friends or co-workers (9.4%), marital problems or divorce (9.4%), or parental death or illness (7.8%). Abuse (either sexual or physical, adult or child) was a relatively uncommon topic (4.5%).

We also examined the language used in the writings by averaging the LIWC indices over the 4 writing days. It is noteworthy that participants in both groups generated fairly long writings that were of similar length (word count: disclosure: M = 469, SD = 253; Control: M = 407, SD = 205.9, p = .26). As expected, disclosure group writings (compared with control group writings) contained substantially more affect words (M = 5.1, SD = 1.2 vs. M = 2.1, SD = 1.1), cognitive words (M = 7.0, SD = 1.5 vs. M = 3.6, SD = 1.5), and bodily-related words (M = 1.5, SD = 0.9 vs. M = 0.8, SD = 0.4) (all p < .001). Thus, although both groups wrote for an equivalent amount, the content differed as expected.

Effects of Writing on Immediate Negative Mood

We hypothesized that disclosure writing would lead to an increase in immediate negative mood compared with control writing. Table 2 presents these data. There was a significant group effect, F(1, 69) = 12.4, p < .001, but no day effect, F(3, 67) = 0.37, p = .77, or group by day interaction, F(3, 67) = 0.39, p = .78. Compared with control writing, disclosure led to increases in immediate negative mood from before to after writing, and this effect did not attenuate or increase over the four days.

Table 2.

Group Comparisons on Changes in Negative Mood (Post-writing minus pre-writing) for Each of the 4 Writing Days (n = 72)

| Experimental Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Writing Day | Disclosure Mean (SD) |

Control Mean (SD) |

| Day 1 | 0.55 (1.49) | −0.17 (0.81) |

| Day 2 | 0.45 (1.33) | −0.11 (0.88) |

| Day 3 | 0.74 (1.51) | −0.16 (0.59) |

| Day 4 | 0.43 (1.14) | −0.17 (0.75) |

Values presented are the mean change score (post-writing minus pre-writing) from ratings (0 to 6) made on six moods that were averaged into a single composite: sad, angry, afraid, guilty, happiness (reversed), and calmness (reversed).

Health Effects at 1-Month Follow-up

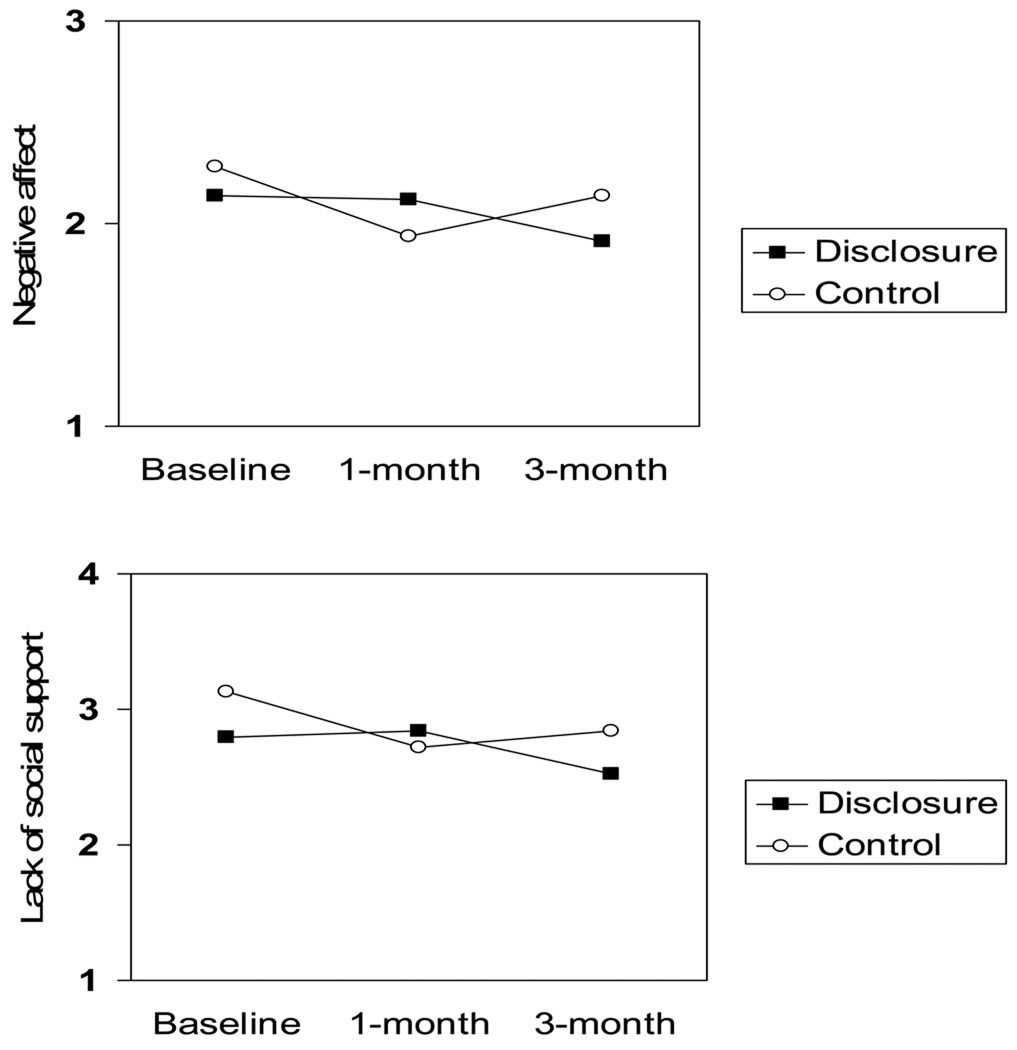

Of the 72 completers, 69 conducted the 1-month follow-up (one disclosure and two control group participants missed it, although all three of them completed the 3-month follow-up). Table 1 shows the F- and p-values from the group × time effect from the repeated measures ANOVA next to each outcome measure’s 1-month and 3-month values. Both types of effect sizes are also shown next to each measure at each follow-up point. As expected, there were no significant main effects of either group or time at the 1-month follow-up for any of these analyses, so these non-significant main effects are not presented. On the primary outcome measure of global impact, the group × time effect of disclosure writing at 1-month was not significant, F(1, 67) = 0.90, p = .34. On the secondary measures, the disclosure group reported significantly more improvement in sleep quality than occurred in controls, F(1, 65) = 6.15, p = .02. This effect was due both to marginally significant improvement in the disclosure group, t(36) = 1.90, p = .07, and to some worsening of the control group, t(29) = 1.63, p = .11. The disclosure group was not significantly better than the control group on any other measure. Interestingly, the group × time effects on negative affect, F(1, 67) = 4.07, p = .048, and lack of social support, F(1, 67) = 5.10, p = .03, at 1-month follow-up showed a different pattern, with the control group developing significantly less negative affect and more social support from baseline than the disclosure group. These effects were due solely to improvements in the control group on NA, t(31) = 3.15, p = .004, and social support, t(31) = 3.27, p = .003, rather than to any change in the disclosure group (NA: p = .66; social support, p = .72). Figure 1 presents these effects in graphic form.

Figure 1.

Differences between emotional disclosure and control groups on negative affect (top) and lack of social support (bottom) from baseline to 1-month and 3-month follow-ups. The control group improved more than the disclosure group from baseline to 1-month follow-up, but groups were no longer different at the 3-month follow-up.

Health Effects at 3-Month Follow-up

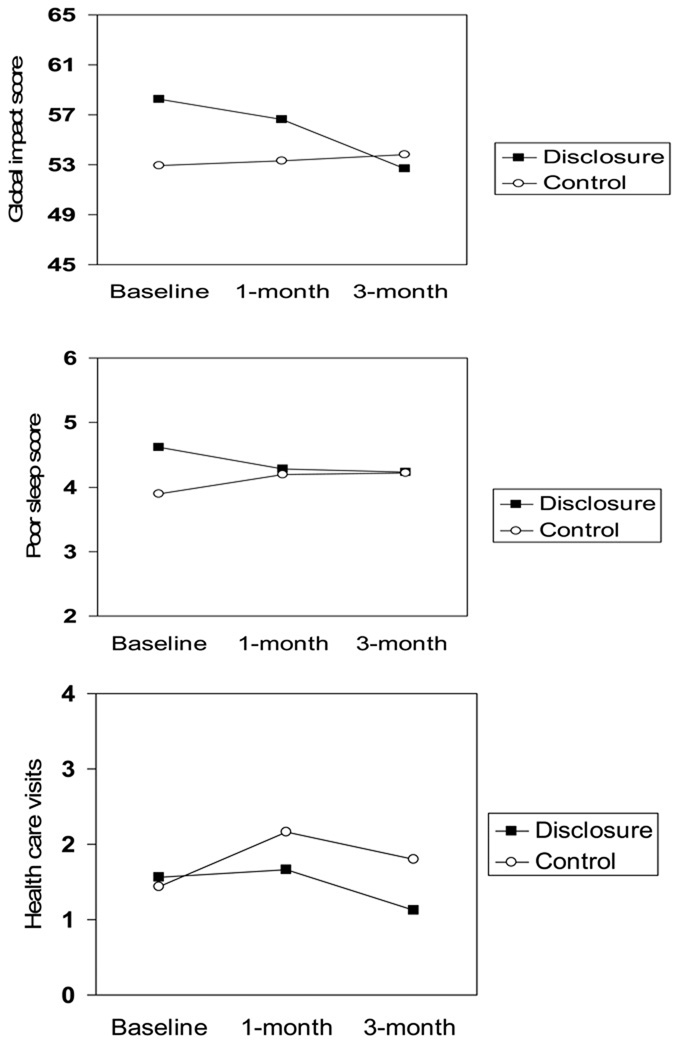

Of the 72 completers, 68 conducted the 3-month assessment (four participants—two from disclosure and two from control—missed it, and these participants were different than the three who missed the 1-month follow-up). As expected, there were no significant main effects of either group or time. Table 1 shows that the findings at 3-month follow-up are quite different than those at 1-month, with a consistent pattern of more improvement from baseline for the disclosure group than for the control group. On the primary outcome of global impact, the significant group × time effect, F(1, 66) = 4.48, p = .04, indicated that the disclosure group improved more than the control group, with ES = 0.34 and d = 0.50. The effect was due solely to improvement from baseline in global impact for the disclosure group, t(35) = 2.54, p = .02, relative to no change for the control group (p = .74). Figure 2 presents the data for this measure.

Figure 2.

Differences between emotional disclosure and control groups on global impact (top), sleep quality (middle), and health care use (bottom) from baseline to 1-month and 3-month follow-ups. The disclosure group improved more than the control group from baseline to 3-month follow-up on these three measures.

There were significant group × time effects for two of the secondary outcome measures, poor sleep, F(1, 63) = 7.81, p = .007, and health care utilization, F(1, 65) = 3.94, p = .05 (see Figure 2), and the physical disability measure showed a marginal group × time effect, F(1, 66) = 3.66, p = .06; all three effects indicated more improvement for the disclosure group than the control group. For these measures, the degree of disclosure group improvement was approximately of the same magnitude as the degree of worsening shown by controls. The disclosure group showed some improvement in sleep, t(35) = 2.42. p = .02, health care utilization, t(34) = 1.47, p = .15, and disability, t(35) = 1.56, p = .13, compared to some worsening for the control group in sleep, t(28) = 1.60, p = .12, health care utilization, t(31) = 1.39, p = .18, and disability, t(31) = 1.17, p = .25. Note that the effect size (d) for these measures ranged from .46 to .66. Secondary measures of pain and fatigue showed similar, albeit non-significant patterns as these other measures, with d values of .34 or .30, respectively. Finally, the group differences for negative affect and social support at 1-month were fully eliminated by 3 months, as shown in Figure 1.

Analyses on the Intent-to-Treat Sample

Compared with completers, drop-outs were more likely to be male (n = 4, 36.4% of drop-outs; p < .001) and were marginally more likely to lack a partner (n = 6; 54.5%; p = .08) and have lower income (p = .06). Drop-outs had poorer health than completers on baseline global FM impact, pain, physical dysfunction, fatigue, and negative affect (all p < .10) but not on other measures (all p > .30). Importantly, the proportion of drop-outs and completers assigned to each writing group was similar, p = .50, indicating no differential drop-out between groups.

The fact that drop-outs differed from completers at baseline makes it important to determine whether the group effects of disclosure writing above noted with the completer sample also hold for the full ITT sample. Thus, we repeated the above analyses on the ITT sample. For 1-month outcomes, the group × time effects found with the completer sample remained the same: disclosure writing led to more improvement in sleep quality than control writing, F(1, 77) = 6.08, p = .016, but control writing led to a greater reduction in negative affect, F(1, 81) = 4.12, p = .046, and greater increase in social support, F(1, 81) = 5.13, p = .026 than did disclosure writing. Again, neither the primary measure of global impact, F(1, 81) = 0.90, p = .35, nor the other outcome measures showed significant group × time effects at 1-month follow-up (physical disability: p = .13; pain, p = .08; fatigue: p = .10, health care utilization, p = .17).

For 3-month outcomes, analyses of the ITT sample were also essentially the same as with the completer sample. For the primary measure of global impact, the significant group × time interaction indicated greater improvement of the disclosure group relative to the control group, F(1, 81) = 4.23, p = .04. Similarly, disclosure writing led to more improvement in sleep quality, F(1, 77) = 7.67; p = .007, reduction in health care utilization, F(1, 81) = 3.87, p = .05, and marginally improved physical disability, F(1, 81) = 3.63, p = .06, compared with control writing. The group × time effects for the other variables were not significant (fatigue: p = .10; pain: p = .16; negative affect: p = .64; lack of social support: p = .87). In summary, the significant effects of disclosure writing observed in the completer sample also held for the ITT sample.

Discussion

The results of this randomized, controlled study of people with FM suggest that at-home written emotional disclosure leads to a greater degree of improvement on various health indices 3 months after writing than does emotionally neutral control writing. These results occurred not only for those who completed the intervention and provided outcome data, but also for all who were randomized. Although several caveats to this general conclusion are discussed below, this study suggests that written disclosure has some potential to benefit people with health problems (18 – 27). The results also support the findings of Broderick et al. (63), who found similar effect sizes of the benefits of written disclosure among women with FM who wrote under controlled conditions in the laboratory.

This generally positive conclusion about the effects of written disclosure in FM, however, needs to be tempered by a critical examination of our findings, which reveals several points of caution. These caveats are the delayed health benefits of disclosure, the short-term improvement in the control group, and the fact that disclosure’s benefits were due, in part, to the disclosure group starting at a somewhat poorer health status than controls and to some minor worsening over time of the control group on some measures. These issues are discussed in turn.

The improvements stemming from written disclosure were delayed and generally not apparent until 3 months after writing. Although there were non-significant trends in the data for disclosure-induced improvements at 1-month follow-up, the benefits were stronger and more consistent across measures at 3-month follow-up. Broderick et al. (63) also found positive effects among FM patients at 4-month follow-up, although that study did not evaluate outcomes earlier, so it is not known at what time the benefits occurred. Studies of written disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis (18, 27) and breast cancer (20) have found benefits at 3-month follow-ups, but not at earlier time points, at least on some measures. This pattern of findings suggests that some passage of time may be required for the benefits of disclosure to occur, at least in some populations. It is noteworthy that in some studies, writing-induced arousal or negative mood habituates over the days of writing, and this habituation predicts symptom improvement 1 month later (75), suggesting that a stress resolution process is occurring while writing. Yet, in the current study of FM, we found that disclosure writers did not evince an attenuation or habituation of negative mood over the 4 writing days, suggesting that stress resolution did not occur while writing. Thus, it is possible that health benefits were delayed more than a month while other mediating processes occurred. Such processes may include continued emotional processing, extinction of negative emotion, changes in cognitions pertaining to self and others, and decisions to communicate or approach relationships differently. Furthermore, initial cognitive / affective improvements may require additional time to manifest in improved physical health and functioning, particularly for measures such as health care utilization. Unfortunately, no study of emotional disclosure has identified the cognitive, affective, behavioral, or interpersonal processes that occur after disclosure and that mediate its effects on health. Clearly, these speculations about mechanisms require further study.

A second caution about the apparent benefits of disclosure in this study is that the disclosure group was significantly worse than the control group on negative affect and social support at 1-month follow-up, although these differences disappeared by 3 months. Although most studies do not show any negative effects of disclosure, we know of at least four prior studies that have shown similar findings with at least some of their outcome measures (10, 15, 38, 39). Thus, it is possible that disclosure leads not only to an immediate negative mood, but also to a negative subjective state that lasts for several weeks or more. It is important to note, however, that in the current study, it was the control group that improved on mood and perceived support from baseline to 1-month, whereas the disclosure group remained unchanged from baseline. Because we would not expect any natural improvement in these measures over one month, the most logical interpretation is that writing about time management in this study temporarily improved people’s mood and self-perceptions, whereas disclosure writing did not. It is noteworthy that control writing led to small reductions in negative mood during each of the writing days, suggesting that control writing might be somewhat uplifting. The time management writings contained as many words as the disclosure writings, and an examination of the control writings suggested that many participants appeared to actively participate in this exercise. Furthermore, time management writing may evoke positive expectancies; in a study of people with rheumatoid arthritis, we found that the credibility of time management writing was as credible a stress management technique as disclosure writing (unpublished data). It is also possible that writing about how one manages one’s time provides a greater sense of control in the short-term, but unless followed by actual behavior changes, such positive effects will be short-lived. These observations suggest that we did not find a true worsening of mood and perceived support after disclosure writing, but a temporary positive response to control writing. Of course, testing this would require a design that included a no intervention control group.

A third caveat about the apparent benefits of written emotional disclosure in FM pertains to the baseline values of the groups. Despite randomization that created groups that were equivalent on demographics, the disclosure group had poorer health at baseline than the control group on several measures. As a result, although the disclosure group improved more than the control group on four measures over the 3-month follow-up, the somewhat different baseline points led to 3-month outcome levels in which the disclosure group was little different than the controls. We do not know whether the significantly greater amount of change observed in the disclosure group would have occurred if the group had started at a healthier baseline that was equivalent to the baseline of the control group; however, an examination of only the outcome values obtained in the study suggest limited clinical significance.

Finally, although the disclosure effect for the primary measure of global impact was due solely to improvement in the disclosure group, the group effects on disability, sleep quality, and health care use were due, in part, to some modest (although non-significant) worsening of the control group at 3 months. Such control group worsening has been seen in a number of disclosure studies (e.g., 7, 15, 64) and has been a cause of concern (76) because its source is unknown. In this study, some minor worsening may be the natural course of FM, which is known to progress over time and which was prevented or buffered by written disclosure. However, this speculation merits further study.

Several of our methodological decisions, such as having few exclusion criteria, using unsupervised writing in the home environment, and conducting assessments through the mail, have the advantage of increasing generalizability or external validity of this study. The trade-off, however, is reduced experimental control and increased sample and measure heterogeneity, which likely led to greater response variability and smaller effects. In addition, our use of only self-report measures raises concerns that the findings might be due to experimental demand. Demand effects, however, are not consistent with the finding of immediate negative mood effects, control group superiority in negative affect and social support at 1-month follow-up, or delayed benefits of disclosure. Nonetheless, future research should employ a wider variety of methods, including diary or ecological momentary assessments of symptoms, actigraphy measures of movement, observational measures of pain behavior, and a better validated measure of sleep quality over multiple nights, or perhaps even polysomnography. Finally, although we have suggested that written disclosure might be useful for FM patients because of relatively high levels of unresolved stress in this population, we did not measure PTSD or unresolved stress in our participants. The disclosure writings generally did not reveal highly traumatic or life-threatening stressors such as sexual or physical abuse, although seemingly less intense stressors such as family conflict and others’ invalidation of one’s health problems can still lead to substantial symptoms of distress along with avoidance, intrusions, and other PTSD symptoms.

Research and Clinical Implications

This study has implications for research and clinical practice. Follow-up durations of disclosure studies need to be long enough to identify possible delayed effects. Short follow-up durations, such as only 1 month, may miss such effects. Indeed, if we had stopped our study at a 1-month follow-up, we would have concluded not only that written disclosure is ineffective, but that it is potentially harmful to mood and perceived support. Earlier findings of negative effects of disclosure after 5 or 6 weeks with PTSD patients or psychiatric inmates (38, 39) should be viewed cautiously, given that longer follow-ups were not conducted in those studies, thus obviating the ability to determine whether benefits would have occurred eventually. Also, few studies have used long follow-ups to test the duration of disclosure’s effects. A noteworthy exception is the study of patients with FM by Broderick et al. (63), which included a 10-month follow-up and found that the initial positive effects of disclosure at 4 months had weakened by 10 months and were no longer significantly different between groups. We also suspect that the time course of the effects of disclosure may vary by population, and multiple, repeated assessments may be necessary to track the time course as well as test potential mediators.

The apparent positive effects of written disclosure for FM, first demonstrated by Broderick et al. (63) and generally supported by the current study, are noteworthy for several reasons. First, currently available treatments for FM, including medication, exercise, and cognitive-behavioral techniques, have only limited efficacy, and written emotional disclosure has the potential to fill a gap in the treatment of these patients, particularly because it directly targets stress resolution. Second, these two studies of written disclosure in FM, along with studies showing the benefits of disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis (18, 27) and chronic pelvic pain (26), suggest that that directly disclosing and processing negative emotional experiences can benefit people with various chronic pain disorders. Most cognitive-behavioral interventions for chronic pain minimize the experience and expression of negative emotions through techniques such as relaxation, distraction, or cognitive reappraisal. Yet, the positive effects of emotional disclosure on patients with chronic pain suggest that encouraging emotional awareness and expression can be salutary in these populations. Finally, this study shows that the benefits of written disclosure for people with FM may generalize beyond writing in the laboratory to writing at home. This is important because it is likely that the translation of this intervention to practice will result in writing occurring in relatively unstructured and unsupervised settings.

Yet, we doubt that written emotional disclosure is a stand-alone intervention for FM or most other problems. Our effects were modest in size, did not significantly improve pain and fatigue—the central complaints of people with FM—and most participants continued to have substantial health problems that warranted intervention. Overall, although the effects were statistically significant, the clinical significance of written disclosure as conducted in this study was limited. Furthermore, interest in and willingness to engage in writing (and to focus on feelings) may be more accepted among certain subgroups, such as those with more education or comfort with writing about feelings. This suggests that studies might examine ways to enhance the benefits of written disclosure in FM and other clinical populations. For example, providing tailored feedback unique to the person’s writing might be tested. Parametric manipulations, such as longer or more frequent writing sessions as well as booster sessions may prove helpful. We also encourage research that integrates written disclosure with other techniques, such as cognitive-behavioral interventions, to determine whether outcomes are enhanced. Finally, as Leserman (77) notes, we do not know whether therapist-directed trauma processing interventions, such as the empirically-supported treatment of imaginal exposure therapy for PTSD, will help people with FM or other chronic pain problems who have unresolved stressors. These proposals await testing.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the dissertation of the first author, conducted under the direction of the second author. The research was supported by a dissertation grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, and in part by a Post-doctoral Fellowship Award and Clinical Science Award from the Arthritis Foundation, and by NIH grant R01 AR049059. The authors thank the Arthritis Foundation for their assistance in recruitment and Heather Koch and Ayna Johansen for their assistance in data collection and coding.

Footnotes

Data from this study were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society, Phoenix, Arizona, in 2003.

Contributor Information

Mazy E. Gillis, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan

Mark A. Lumley, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan

Angelia Mosley-Williams, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan

James C.C. Leisen, Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan

Timothy Roehrs, Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan

References

- 1.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experimental avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austenfeld JL, Stanton AL. Coping through emotional approach: a new look at emotion, coping, and health-related outcomes. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1335–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenzlaff RM, Wegner DM. Thought suppression. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:59–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lepore SJ, Greenberg MA. Mending broken hearts: Effects of expressive writing on mood, cognitive processing, social adjustment and health following a relationship breakup. Psychology & Health. 2002;17:547–560. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ullrich PM, Lutgendorf SK. Journaling about stressful events: effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:244–250. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg MA, Stone AA. Emotional disclosure about traumas and its relation to health: Effects of previous disclosure and trauma severity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1992;63:75–84. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg MA, Wortman CB, Stone AA. Emotional expression and physical heath: Revising traumatic memories or fostering self-regulation? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;71:588–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King LA, Miner KN. Writing about the perceived benefits of traumatic events: Implications for physical health. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:220–230. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esterling BA, Antoni MH, Fletcher MA, Margulies S, Schneiderman N. Emotional disclosure through writing or speaking modulates latent Epstein-Barr virus antibody titers. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW, Davison KP, Thomas MG. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to a hepatitis B vaccination program. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:787–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron LD, Nicholls G. Expression of stressful experiences through writing: Effects of a self-regulation manipulation for pessimists and optimists. Health Psychology. 1998;17:84–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennebaker JW, Colder M, Sharp LK. Accelerating the coping process. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;58:528–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein K, Boals A. Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:520–533. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner LJ, Lumley MA, Casey RJ, et al. Health effects of written emotional disclosure in adolescents with asthma: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj048. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4160–4168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:272–275. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116782.49850.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solano L, Donati V, Pecci F, Persichetti S, Colaci A. Postoperative course after papilloma resection: effects of written disclosure of the experience in subjects with different alexithymia levels. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:477–484. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000035781.74170.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidron Y, Duncan E, Lazar A, Biderman A, Tandeter H, Shvartzman P. Effects of guided written disclosure of stressful experiences on clinic visits and symptoms in frequent clinic attenders. Family Practice. 2002;19:161–166. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Moor C, Sterner J, Hall M, et al. A pilot study of the effects of expressive writing on psychological and behavioral adjustment in patients enrolled in a Phase II trial of vaccine therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Health Psychology. 2002;21:615–619. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg HJ, Rosenberg SD, Ernstoff MS, et al. Expressive disclosure and health outcomes in a prostate cancer population. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2002;32:37–53. doi: 10.2190/AGPF-VB1G-U82E-AE8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman SA, Lumley MA, Dooley JA, Diamond MP. For whom does it work? Moderators of the effects of written emotional disclosure in a randomized trial among women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:174–183. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116979.77753.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley JE, Lumley MA, Leisen JCC. Health effects of emotional disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Health Psychology. 1997;16:331–340. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broderick JE, Stone AA, Smyth JM, Kaell AT. The feasibility and effectiveness of an expressive writing intervention for rheumatoid arthritis via home-based videotaped instructions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:50–59. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker BL, Nail LM, Croyle RT. Does emotional expression make a difference in reactions to breast cancer? Oncology Nursing Forum. 1999;26:1025–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris AHS, Thoresen CE, Humphreys K, Faul J. Does writing affect asthma? A randomized trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:130–136. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146345.73510.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivkin ID, Gustafson J, Weingarten I, Chin D. The effects of expressive writing on adjustment to HIV. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9051-9. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bower JE, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Fahey JL. Finding positive meaning and its association with natural killer cell cytotoxicity among participants in a bereavement-related disclosure intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25:146–155. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H, Zech E, van den Bout J. Does disclosure of emotions facilitate recovery from bereavement? Evidence from two prospective studies. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klapow JC, Schmidt SM, Taylor LA, et al. Symptom management in older primary care patients: feasibility of an experimental, written self-disclosure protocol. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:905–911. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_part_2-200105011-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schilte AF, Portegijs PJ, Blankenstein AH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of disclosure of emotionally important events in somatisation in primary care. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ames SC, Patten CA, Offord KP, Pennebaker JW, Croghan IT, Tri DM, Stevens SR, Hurt RD. Expressive writing intervention for young adult cigarette smokers. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:1555–1570. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisina PG, Borod JC, Lepore SJ. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2004;192:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138317.30764.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gidron Y, Peri T, Connolly JF, Shalev AY. Written disclosure in posttraumatic stress disorder: Is it beneficial for the patient? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184:505–507. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199608000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards JM, Beal WE, Seagal JD, Pennebaker JW. Effects of disclosure of traumatic events on illness behavior among psychiatric prison inmates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:156–160. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sloan DM, Marx BP. A closer examination of the structured written disclosure procedure. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:165–175. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lepore SJ, Greenberg MA, Bruno M, Smyth JM. Expressive writing and health: Self-regulation of emotion-related experience, physiology, and behavior. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure: How expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pennebaker JW, Keough KA. Revealing, organizing, and reorganizing the self in response to stress and emotion. In: Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, editors. Self, social identity, and physical health: Interdisciplinary explorations. 1999. pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sloan DM, Marx BP. Taking pen to hand: Evaluating theories underlying the written disclosure paradigm. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2004;11:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Hembree EA, Alvarez-Conrad J. Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1022–1028. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarrier N, Pilgrim H, Sommerfield C, Faragher B, Reynolds M, Graham E, Borrowclough C. A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1995;38:19–28. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ. Aspects of fibromyalgia in the general population: sex, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms. Journal of Rheumatology. 1995;22:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldenberg DL, Simms RW, Geiger A, Komaroff AL. High frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with chronic fatigue seen in a primary care practice. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1990;33:381–387. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker EA, Keegan D, Gardner G, Sullivan M, Bernstein D, Katon WJ. Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: II. Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and neglect. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:572–577. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Houdenhove B, Neerinckx E, Lysens R, et al. Victimization in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in tertiary care: a controlled study on prevalence and characteristics. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:21–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderberg UM, Marteinsdottir I, Theorell T, von Knorring L. The impact of life events in female patients with fibromyalgia and in female healthy controls. European Psychiatry. 2000;15:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McBeth J, Macfarlane GJ, Benjamin S, Morris S, Silman AJ. The association between tender points, psychological distress, and adverse childhood experiences: a community-based study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1999;42:1397–1404. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1397::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yunus MB. Psychological aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome: a component of the dysfunctional spectrum syndrome. Baillieres Clinical Rheumatology. 1994;8:811–837. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman JJ, Turk DC, Okifuji A. Prevalence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms on patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2000;16:127–134. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen H, Neumann L, Haiman Y, Matar MA, Press J, Buskila D. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia patients: overlapping syndromes or post-traumatic fibromyalgia syndrome? Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2002;32:38–50. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.33719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bansevicius D, Westgaard RH, Stiles T. EMG activity and pain development in fibromyalgia patients exposed to mental stress of long duration. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2001;30:92–98. doi: 10.1080/03009740151095367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Vulnerability to stress among women in chronic pain from fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23:215–226. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brosschot JF, Aarsse HR. Restricted emotional processing and somatic attribution in fibromyalgia. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31:127–146. doi: 10.2190/K7AU-9UX9-W8BW-TETL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dailey PA, Bishop GD, Russell IJ, Fletcher EM. Psychological stress and the fibrositis/fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology. 1990;17:1380–1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sayar K, Gulec H, Topbas M. Alexithymia and anger in patients with fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology. 2004;23:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-0918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lumley MA, Smith JA, Longo DJ. The relationship of alexithymia to pain severity and impairment among patients with chronic myofascial pain: comparisons with self-efficacy, catastrophizing, and depression. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:823–830. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith JA, Lumley MA, Longo DJ. Contrasting emotional approach coping with passive coping for chronic myofascial pain. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:326–335. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2404_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE. Written emotional expression produces health benefits in fibromyalgia patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:326–334. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000156933.04566.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park CL, Blumberg CJ. Disclosing trauma through writing: Testing the meaning-making hypothesis. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2002;26:597–616. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC): LIWC2001. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Labouvie-Vief G, Lumley MA, Jain E, Heinze H. Age and gender differences in cardiac reactivity and subjective emotion responses to emotional autobiographical memories. Emotion. 2003;3:115–126. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X. Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. Journal of Rheumatology. 1991;18:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.White KP, Harth M. An analytical review of 24 controlled clinical trials for fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) Pain. 1996;64:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dunkl PR, Taylor AG, McConnell GG, Alfano AP, Conaway MR. Responsiveness of fibromyalgia clinical trial outcome measures. Journal of Rheumatology. 2000;27:2683–2691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. AIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1992;35:1–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46:1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roehrs T, Bonahoom A, Pedrosi B, Rosenthal L, Roth T. Treatment regimen and hypnotic self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s002130000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sloan DM, Marx BP, Epstein EM. Further examination of the exposure model underlying the efficacy of written emotional disclosure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:549–554. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neale JM, Cox DS, Valdimarsdottir H, Stone AA. The relation between immunity and health: comment on Pennebaker, Kiecolt-Glaser, and Glaser. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:636–637. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leserman J. Sexual abuse history: Prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:906–915. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188405.54425.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]