Abstract

Background

Older adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) typically take more than five medications and have multiple prescribing physicians. Little however is known about how they prioritize their medical conditions or decide which medications to take.

Methods

Semistructured interviews (average length 40 minutes) with twenty community-dwelling adults with CKD stages 3-5D, receiving nephrology care at a tertiary referral center. Respondents were asked about medications, prescribing physicians, and medication-taking behaviors. We performed thematic analysis to explain patients’ decisions regarding medication prioritization, understanding, and adherence decisions.

Results

Participants (age range, 55–84 years; mean, 72) took 5–14 prescribed medications, had 2–9 physicians, and 5–11 comorbid conditions. All had assigned implicit priorities to their medications. While the majority expressed the intention to be adherent, many regularly skipped medications they considered less important. Most identified the prescribing physician and indication for each medication, but there was often substantial discordance between beliefs about medications and conventional medical opinion. Respondents prioritized medications based on the salience of the particular condition, perceived effects of the treatment, and on the barriers (physical, logistic, or financial) to taking the prescribed drug. Side effects of medications were common and anxiety-provoking, but discussions with the prescribing physician were often delayed or unfulfilling for the patient.

Conclusions

Polypharmacy in CKD patients leads to complex medication choices and adherence behaviors in this population. Most of the patients we interviewed had beliefs or priorities that were non-concordant with conventional medical opinion, but patients rarely discussed these beliefs and priorities, or the resultant poor medication adherence, with their physicians. Further study is needed to provide quantitative data on the magnitude of adherence barriers. It is likely that more effective communication about medication taking could improve patients’ health outcomes and reduce potential adverse drug events.

Index words: qualitative, chronic kidney disease, medication adherence, elderly

Daily medication use is a cornerstone of disease management in nearly all chronic diseases, but medication adherence is often a major barrier to achieving treatment goals. In various settings, between 30–60% of patients with chronic illness are not adherent to medical therapy; medication non-adherence can be both dangerous and costly, leading to hospitalization, adverse effects, and progression of disease.1 To address medication non-adherence in any clinical setting, it is necessary to understand the problems particular to that setting. Reasons for medication non-adherence have been shown to vary by disease,2, 3 and by characteristics of the specific medicines prescribed.4

In the setting of chronic kidney disease (CKD), patients have multiple comorbid conditions, and experience high pill burden and treatment burden.5 Diabetes and hypertension frequently precede CKD diagnosis, and cardiovascular disease is often seen well before kidney disease becomes symptomatic. Patients referred for CKD care often carry several other chronic disease diagnoses, have several prescribing physicians, and take multiple medications by the time they are seen by a nephrologist.

Thus, multiple disease-based guidelines may apply to these patients, including not only the KDOQI guidelines6 but also (most commonly) guidelines applicable to heart disease, hypertension, bone disease, and diabetes. Further, since the main burden of CKD is in older adults, considerations related to medication adherence in older populations are particularly relevant. In the geriatric literature, where multiple comorbid conditions are the norm, the application of multiple guidelines and polypharmacy have been suggested to be risk factors for non-adherence. Depression is also highly prevalent in CKD populations7 and in older adults and is a known risk factor for low adherence.8 In multiple disease-specific settings and in meta-analyses, non-adherence has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for poor clinical outcomes,9–11 so recognition and assessment of non-adherence and its associated risk factors should be a priority for healthcare providers.

In other aspects of nephrology practice, such as hypertension management12 and kidney transplantation,13, 14 adherence rates, risk factors for non-adherence, and interventions to promote adherence have been investigated, but in view of the complexity of the medical regimens recommended for older CKD patients, surprisingly little is known about how patients with this condition view their medications, integrate advice from different providers, or decide which medications to take regularly.

Medication adherence decisions have been shown to vary dramatically across different health conditions and treatment regimens. Understanding individuals’ decision-making processes is best accomplished through qualitative studies which allow exploration of a full range of responses without the limits set by questionnaire or survey instrument data collection. Thus, we designed this study to explore, via in-depth, semistructured interviews, the major themes surrounding medication use and adherence decisions in older kidney disease patients.

Methods

Participants

This study recruited patients with CKD stages 3-5D from two ongoing observational cohort studies at an academic medical center. Patients had to be English-speaking, be in control of organizing their own medication, and, to facilitate participation, had to have an upcoming scheduled visit to the medical center. We included patients 55 years of age and older; in our final sample, all but one participant was over 60 years old. We excluded patients currently taking transplant-related immunosuppressive therapy, regardless of allograft function, because our intention was to understand adherence barriers to non-transplant medications. We reviewed charts of patients enrolled in the two ongoing studies and purposely sampled across different social and ethnic backgrounds, different stages of kidney disease, and different causes of disease. Thirty patients were contacted by phone or in person, of whom 22 volunteered to participate in the study; 20 were ultimately interviewed. The interviewer (DER) was not actively involved in clinical care for any of the participants. Inconvenience or lack of time were the major stated reasons for non-participation. No compensation was provided. The study was approved by the Tufts Medical Center IRB.

Data Collection

Interviews were held in clinic rooms, nearby conference areas, or in the dialysis unit. All interviews were conducted by DER between January and May 2009, following a script adapted from Elliott et al’s study of medication choices in older adults15 and Laws et al’s study of complex therapeutic choices in HIV.3 Several pre-specified topics [Box 1] were covered in the interview script [Item S1, provided as online supplementary material available with this article at www.ajkd.org].

Box 1. Topics Discussed in the Semistructured Interviews.

Knowledge and beliefs about individual medicines and combination therapies

Prioritization of individual comorbid conditions and associated medications

Prioritization of various comorbid conditions and physicians’ recommendations

Knowledge and beliefs about kidney disease and nephrology care

Financial impact of medical care and impact of cost on care

Methods of making decisions about care (ways of seeking information)

Views of physicians’ and patients’ roles in negotiating side effects or other problems with medications

Medication adherence was addressed at multiple opportunities during the interview. Since in the general adherence literature patients are known to underreport non-adherence16 or to report adherence according to personal definitions rather than conventional medical concepts of non-adherence,17 we approached this topic in several ways. We elicited narrative stories of patients’ diagnoses of kidney disease, their current health status, and their beliefs about future health status; during this phase of the interview, medication use was often a theme in responses. We also initiated discussions of each individual medication and the patient’s experience with that medication. We phrased specific questions about adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. As the interview process progressed, specific discussions of themes identified by previous participants as important (such as relationships with physicians) were emphasized.

Patient comorbid conditions were taken from electronic chart reviews and directly from interview data with patients.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed sequentially by the first author (DER) during the acquisition process. DER and MBL assessed the first several transcripts to confirm the effectiveness of the interview guide. DER then abstracted and categorized themes discovered in the data, with reference to pertinent quotations from that transcript following standard qualitative methods.18 Approximately midway through this process, as interviews were still being conducted, she consulted with the second author (MBL) to discuss themes identified to that point, and reach agreement on their plausibility. When new and distinct themes arose we added a new category. Rather than begin with an a priori theoretical perspective, we adopted a pragmatic, ethnographic approach to identifying and organizing narrative themes around the significance and purpose of medication taking behavior, in which the concordance or discordance between patient and physician understanding of medications and medication adherence emerged as a dominant principle. We planned 30 interviews but found that after 15 interviews the major themes appeared to be saturated. The following 5 interviews confirmed this with no new major themes introduced. After DER initially developed the interpretive framework, MBL re-read the transcripts incorporating his interpretation and the two investigators formulated a final interpretive framework.

Results

Participants

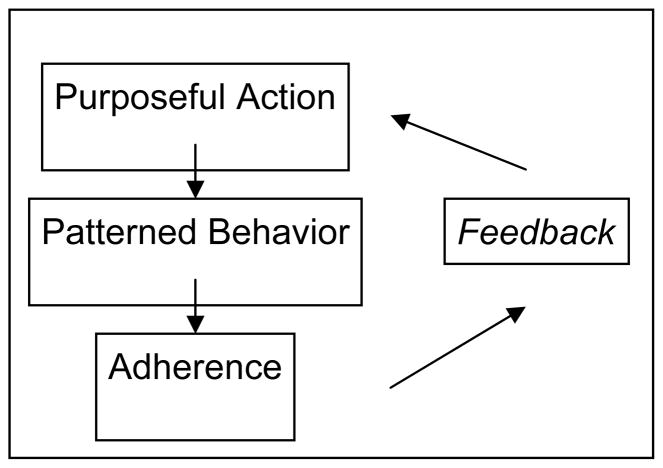

We interviewed 12 men and 8 women [Table 1]. Eight of the interviewees were dialysis-dependent; 12 had CKD stage 3–5. As expected, these individuals had many comorbid conditions and complex medication regimens, typical of older CKD patients.19 While the majority of participants indicated a general intention to be adherent, all participants could identify barriers to consistent medication use. Some participants viewed these barriers as relatively minor, but for many the barriers had led them to non-adherence or to a redefinition of adequate adherence. In discussing adherence barriers, participants referred to issues of communication, paternalism, autonomy, and trust or failure of trust in the physician or medical system. Their statements also revealed a range of beliefs about their health, the relative importance of kidney disease, and the effects of medications. When describing how they assessed the utility of a given medication, participants made use of concepts of action, patterned behavior, and feedback, similar to those outlined in common models of adherence [Figure 1].20

Table 1.

Characteristics of interviewed patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 (60) |

| Female | 8 (40) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 11 (55) |

| African-American | 6 (30) |

| Hispanic | 2 (10) |

| Asian | 1 (5) |

| Age (years) | 73**** (55–84) |

| Non-United States native | 5 (25) |

| English as first language | 16 (80) |

| Cause of kidney disease* | |

| Hypertension | 13 |

| Diabetes | 7 |

| Interstitial disease | 4 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 1 |

| IgA nephropathy | 1 |

| Sarcoid | 1 |

| Kidney disease status | |

| Stages 3–5 CKD** | 12 (60) |

| Stage 5D (hemodialysis-dependent) | 8 (40) |

| No. comorbid conditions | 8 (5–11) |

| Income category (per year, in thousands) | |

| < 20 | 10 (50) |

| 30–40 | 3 (15) |

| 50–75 | 3 (15) |

| >75 | 3 (15) |

| refused | 1 (5) |

| Years of education | 13 (10–20) |

| Yearly self-reported out-of-pocket medication-related expenses*** | $450**** ($120–6000) |

| Burdened by medical costs | 8 (40) |

| No. prescribed medications | 8 (5–14) |

| No. daily doses of medication (pills, injections) | 12 (7–24) |

| No. current physicians (self-report) | 4.7 (2–9) |

Note: except where indicated, values shown are no. (%) or mean (lower-upper limits of range).

Abbreviation: CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Causes listed add to more than 20 as several patients had multiple causes.

eGFR range of 9–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 (median, 39 ml/min/1.73 m2) using IDMS-traceable 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation

18/20 participants reporting

median

Figure 1.

Medication Adherence Action Model. Based on Johnson et al.20

Major Themes

We identified four major themes that participants referred to when discussing medication use: 1) concerns about polypharmacy; 2) medication prioritization; 3) experiences with side effects; and 4) barriers to discussions of adherence with physicians.

Theme 1: Concerns About Polypharmacy

A common theme was concern over the physical difficulty and potential interactions of taking a large number of medications. Although the majority of participants expressed that pill taking was a burden, this was not necessarily associated with reported non-adherence; rather, the burden was weighed against the perceived rationale for the medication.

Pill size, number, and frequency

The burden of pill number or size prompted several participants to note conflict between trying to follow physicians’ recommendations (paternalism) and using their own judgment (autonomy) to assess whether the recommendations were valid.

“They sit in at least two different buckets. I bring in one bucket to the kitchen and gag down whatever, and then the next one. It’s really dreadful… Instead of taking two or three pills, I’m – you know, you can’t count. It’s just too many.” –Participant 16, 8 prescription and 4 over-the-counter (OTC) medications

“I take them when people tell me to take them… I’m not even sure what they are… I have to talk to all of [the doctors] … because otherwise in the morning I’ll end up taking ten pills.” – Participant 4, 10 prescription medications

Systems for coping with polypharmacy

Participants had devised numerous systems to aid in taking complex regimens, including pill boxes and sorting devices, associated activities, family support, or combinations of these. Once the decision was made to take medication, most patients seemed able to create the systems necessary to allow this.

“[My wife] fills the pill thing up every week… and she bugs me every morning. If I forget, when I come back, the pill’s out, and there’s [my wife]. She’s my system.” – Participant 9, 7 prescription and 2 OTC medications

“And I usually say my prayers at night, and my prayers – my medicine is part of my prayers, okay? So that’s a good way to remember it. Like, I gotta say my prayers; I have to take my [medication] and that’s one of the ways I do it.” –Participant 13, 8 prescription medications

Even for medications participants considered to be critical to their health, pill frequency or dosage forms were challenges to the patterned behavior necessary for adherence. One participant with recurrent hyperkalemia discussed his problems taking Kayexalate.

“It’s not in a [pill] container. It has to move – it’s on the counter all the time, but it has to move up to the front of the counter or I forget.” – Participant 9

Others discussed simple issues like forgetting medications at bedtime.

“On occasion something just – I’m too tired and I forget about it and I get in bed and go, ‘Oh my God.’ I gotta get outta bed?” – Participant 1, 5 prescription and 2 OTC medications

Trust, physician motivation, and polypharmacy

Cost, and more importantly, physician earnings based on prescribing patterns were mentioned by multiple participants as explanations for polypharmacy and as potential reasons to reconsider the wisdom of physicians’ recommendations.

“These [two medicines] are for cholesterol, and I was only taking one pill for cholesterol, and my cholesterol was fine. Sometimes I think these salesmen come around and talk to the doctors and sell them a bill of goods, and the next thing you know, you’re on it.” –Participant 13, 8 prescription medications

Theme 2: Medication Prioritization

We found that most participants had implicit ranking or prioritization of their medicines, and that this ranking was associated with likelihood of adherence to a given component of the medication regimen. When asked directly, the majority said that their blood pressure medications were the most important. For some, however, medications that provided noticeable feedback – such as relieving symptoms or having noticeable effects -- were seen as most important. Thus, medications such as lipid-lowering agents were perceived as less important.

“And I said, yeah, well, no problem I’m gonna take [niacin]. It’s a benefit for my heart…I’m gonna go for it. And I took it for a while… but I didn’t notice any benefit. I mean, nothing direct. I didn’t feel it. If I take niacin, or I don’t take it, no difference. I don’t take metoprolol, I know there’s a difference. I feel different, I feel some fatigue, I feel something missing.” –Participant 2, 11 prescription medications

Participants who had pain compared the importance of symptomatic vs. asymptomatic disease in prioritizing medication use.

“But if you get to be in pain, you don’t have to be reminded to take it multiple times. You know that’s the only way the pain will stop, whereas this thing [kidney disease] is not a pain thing. It’s a calcium thing, or whatever it is.” –Participant 16, 8 prescription and 4 OTC medications

Multiple respondents had identified medications which they believed could be taken less frequently than prescribed; these included electrolyte supplements, phosphorus binders, lipid-lowering agents, and psychiatric agents. In most of these cases, the medication being taken less frequently than prescribed was one for a condition the participant viewed as asymptomatic or relatively low-priority. However, one respondent took sertraline for symptomatic relief only when under stress, contrary to the conventional understanding of how selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors work.

“If I don’t have any stress, not stress but family issues… I don’t take it… But some days, if I can’t cope with what’s going on or there’s too much drama, or too much nonsense, I have to take it.” –Participant 12, 7 prescription medications

Understanding of Kidney Disease and Medication Prioritization

Very few non-dialysis participants could easily explain which medications were helpful for their kidney disease, and most had difficulty explaining how the medications were helpful. In these cases, the medications that were less well understood received lower priority and sometimes lower adherence.

“But these two I really hate taking… I’m not even sure they’re doing any good, but everybody says, ‘You need calcium. You need potassium. You need your supplements.’ So, I’ll know when I get my blood tests. Then I’ll know.” –Participant 16

Some expressed frustration that physicians’ priorities for treatment of hypertension and kidney disease outweighed participants’ priorities for treatment of symptomatic diseases.

“I don’t think they don’t get the problem… when they discovered that the kidneys were bad… then I was referred to the kidney doctor and they got me in here as soon as they could, [but] I have carpal tunnel in both hands, and I tell it to them all the time, and they go, ‘Okay,’ and they write it down, and then… nothing happens.” –Participant 10, 14 prescription and 1 OTC medication

Theme 3: Communication About Side Effects and Medication Decisions

Participants expressed a wide range of concerns about side effects and had often changed their medication taking behavior based on these concerns. A common complaint was the absence of guidance from medical professionals in assessing and evaluating risks of medications. The responsibility for assessing side effects was generally seen as falling on the patient.

“So see these are things doctors never tell you…Everything I get I go home and check it. Every single one of my other medicines say the same thing. And you know, you say: ’Well, which one is it?’” –Participant 1, 5 prescription medications

Several participants mentioned occasions where physicians’ responses to side effects lacked empathy. One patient who had leg edema in reaction to a calcium-channel blocker explained how her physicians’ response to her side effect led her to feel betrayed and to doubt their motivation.

“If you read what’s on the prescription [insert] you’d be dead… but they should’ve said, ‘If you have any side effects such as,’ and then only two or three of the major ones… Those are not discussed. So, I had to assume that there’s nothing adverse except in rare cases. Well, it turns out that’s not true because every one I’ve mentioned the [edema] to, they didn’t blink an eye. They sort of smiled, ‘Oh, we know.’ That irritated me a lot… They acted as if they were getting paid to [prescribe it].” –Participant 16

Several participants noted that physicians, in addition to explaining side effects inadequately or being non-empathetic when side effects occurred, did not validate their concerns or acknowledge that a given reaction was indeed a side effect.

“The problem I see is that it’s making me lose my hair. … They say it ain’t the medicine. But naturally they’re going to say it can’t be the medicine. But what else can it be... I’ve tried stopping them all! I go every other night! Then I notice I don’t lose so much hair… He tell me it ain’t got nothing to do with the medication. But I still believe it does.” –Participant 18, 9 prescription, 1 OTC medication

Another participant who was formerly highly motivated and adherent reported stopping medications entirely for a time after an event which she experienced as a betrayal by her physicians. In these all cases, participants who did not feel their concerns were adequately addressed took on a more autonomous role in assessing whether to take physicians’ advice regarding medications.

By contrast, participants who reported good relationships with their physicians seemed to find it easier to negotiate the initiation of new medications and potential side effects.

“It’s very hard to balance being like scared of stuff versus knowing that you need to do some of the stuff… They usually tell me what they’re giving me and why. And what the result should be and that’s really all I need to know.” –Participant 14, 9 prescription medications

Theme 4: Barriers to Discussions With Physicians About Adherence

In addition to commonly reported problems such as forgetfulness, unexpected changes in routine, or schedule conflicts, some individuals who self-identified as adherent had in fact decided not to take certain medications, or to take one or more medications irregularly, and were adherent only to those medications they considered important. Most participants did not, however, discuss these decisions with their physicians. Participants expressed worry that well-meaning specialists were unable to assess the complexity of their other conditions (such as heart disease, diabetes). Others believed they already knew what the physician would say, and avoided conflict by avoiding discussion of adherence.

“My list over there, it’s about twelve different medicines. So I don’t need to be a genius to realize, that if I take 12 medicines every day, I’m gonna have some side effect. Right or wrong. So, you know. What’s the doctor going to say? You need it. You have to take it. The doctor’s gonna say, well, it causes some side effect, but you need the medicine.” –Participant 2, 11 prescription medications

Another participant who had not discussed adherence decisions with her physician had clear personal judgments about the safety of medications, but felt she did not want to cause conflict by discussing these.

“Niacin’s no good for a person who has gout. You can’t take it. I know it’s good for the heart – they’re doing a study – which I think is wonderful but I’m not gonna take a chance because I read a lot and I read that niacin’s not good because I’m a very acidic person. They want to give me Vitamin D – no, I can’t take that. It’s not good for me.” –Participant 1, 5 prescription medicines

In addition to these cases where individuals avoided conflict with physicians by not discussing adherence issues, one patient mentioned deceiving the physician by taking a medication only prior to clinic visits.

“Oh, she want me to take them potassium [pills], and I … I don’t need them things every day. They got salt in ‘em, to me. They taste salty, but…I said, ‘That kinda pill you – I don’t think I have to take ‘em every day.’ But, when I get ready to go see [the doctor], then I take ‘em, so that there be some in the blood.” –Participant 7, 9 prescription and 1 OTC medication

Discussion

In this study, patients with CKD 3–5 and complicated medication regimens had complex methods for judging the importance of medication use. They weighed possible side effects and risks of polypharmacy against the information they received about potential benefit of medications. Only a few individuals reported discussion of these decisions with their doctors despite significant concerns, a finding consistent with prior studies in older adults.21

Even the participants who self-identified as compliant and who likely did have high adherence rates in our study expressed doubts about the number of medications they took and the risks associated with that intake. Participants listed medications for diseases they perceived as asymptomatic or low-priority as those which they would prefer not to take. Moreover, although all the patients interviewed were being treated by salaried physicians in an academic center, several expressed the belief that physicians were influenced by marketing to prescribe more medication.

Although medication adherence has been extensively explored in hypertension and in kidney transplantation, little study has focused on the care of non-transplant CKD patients. A single previous study in Australian patients with diabetes with kidney disease used similar methods22 and found discordance between providers’ and patients’ views of the importance of kidney-specific medications. The same authors have reported that diabetic kidney disease patients often make medication decisions based on non-medical reasoning.23 Although we did not interview providers and explicitly did not intend to quantify medication adherence in this study, we did see substantial discordance between the medications patients reported taking and the physicians’ documentation of medication use in clinic notes. We also observed numerous instances of non-medical reasoning in participants’ explanations of their decisions. This non-medical reasoning may have been due to poor health literacy, which has recently been highlighted as an area in need of study in CKD populations.24 However, little is known about the relationship between health literacy as commonly measured by tests of basic skills, and patients’ explanatory models of disease and decision making heuristics about treatment and treatment adherence.25, 26

Our findings are in line with previous data from older studies in other medical conditions, in that ‘non-adherent’ behavior in these patients was often a result of considered, if non-biomedical, reasoning rather than irrational behavior or ignorance.27 In our sample, the reasons for nonadherence mentioned by patients were the risks of polypharmacy and associated side effects, doubts about physician motivation, the difficulty of taking medication for asymptomatic conditions, loss of self-efficacy or a sense of betrayal, or the salience of certain comorbid conditions over others. Involuntary barriers, such as forgetting and schedule conflicts, were pervasive, but also rarely discussed with physicians.

Our findings have implications for the care of patients seen in nephrology referral situations. Current evidence-based guidelines often recommend treatment with additional oral medications, including additional antihypertensives, vitamin D analogs, and phosphate binders; these guidelines do not currently focus on strategies for managing polypharmacy or adherence. Thus a typical new patient may receive several new medications specifically prescribed by a nephrologist. Although these additional medications have demonstrable benefits, an important part of an initial visit may be a discussion of the patient’s current regimen and his or her willingness to start new medications. Conversely, primary care physicians considering whether to refer a patient for CKD care may wish to consider a medication review and discussion of patient priorities prior to referral. Interventions to improve adherence to the complex therapies required in kidney disease should take into account patients’ concerns and priorities in order to be most effective.

Our findings are limited by the small sample size and single institution; we cannot necessarily generalize the themes noted here to other CKD clinic settings. For instance, our participants did not focus on cost as a major barrier; this may be a reflection of local health coverage mandates and may not be reflective of the general population. The interviews were conducted in a medical setting, and this may have led to some reluctance on the part of our respondents to speak freely on the topic of medication taking behavior. More quantitative, survey-based studies in larger cohorts may be useful in delineating the range and prevalence of different adherence behaviors in this setting. The advantage offered by our study is that it reveals complex behaviors that could not be easily captured by other more quantitative forms of adherence research. Accordingly, we believe that the insights here have important implications for the care of CKD patients and for future studies of adherence in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: This study was supported in part by grant K24DK078204 to Dr Sarnak from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

N section: Because an author of this manuscript is an editor for AJKD, the peer-review and decision-making processes were handled entirely by an Associate Editor (Dr Kevan Polkinghorne, MBChB, MClinEpi, FRACP, PhD, Monash Medical Centre) who served as Acting Editor-in-Chief. Details of the journal’s procedures for potential editor conflicts are given in the Editorial Policies section of the AJKD website.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Item S1: Interview Guide.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_____) is available at www.ajkd.org.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dunbar-Jacob J, Mortimer-Stephens MK. Treatment adherence in chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Dec;54 (Suppl 1):S57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacey J, Cate H, Broadway DC. Barriers to adherence with glaucoma medications: a qualitative research study. Eye. 2008 Apr 25;23 (4):924–932. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laws MB, Wilson IB, Bowser DM, Kerr SE. Taking antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: learning from patients’ stories. J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Dec;15(12):848–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004 Mar;42(3):200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002 Feb;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Jan;41(1):105–110. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 4;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002 Sep;40(9):794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unruh ML, Evans IV, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB. Skipped treatments, markers of nutritional nonadherence, and survival among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Dec;46(6):1107–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, Whooley MA. Self-reported medication adherence and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Sep 10;167(16):1798–1803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2006 Nov;19(11):1190–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bleser L, Matteson M, Dobbels F, Russell C, De Geest S. Interventions to improve medication-adherence after transplantation: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2009 Aug;22(8):780–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey PE, Flynn ML, Lin S. Medication noncompliance and its implications in transplant recipients. Drugs. 2007;67(10):1463–1481. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767100-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott RA, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS, Safran DG, Soumerai SB. Strategies for coping in a complex world: adherence behavior among older adults with chronic illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jun;22(6):805–810. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0193-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garber MCPMA, Nau DPP, Erickson SRP, Aikens JEP, Lawrence JBMBA. The Concordance of Self-Report With Other Measures of Medication Adherence: A Summary of the Literature. Medical Care. 2004;42(7):649–652. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129496.05898.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudd P. In Search of the Gold Standard for Compliance Measurement. Arch Intern Med. 1979 June 1;139(6):627–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailie GR, Eisele G, Liu L, et al. Patterns of medication use in the RRI-CKD study: focus on medications with cardiovascular effects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005 Jun;20(6):1110–1115. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson MJ. The Medication Adherence Model: a guide for assessing medication taking. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002 Fall;16(3):179–192. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.16.3.179.53008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson IB, Schoen C, Neuman P, et al. Physician-patient communication about prescription medication nonadherence: a 50-state study of America’s seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):6–12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams AF, Manias E, Walker R. Adherence to multiple, prescribed medications in diabetic kidney disease: A qualitative study of consumers’ and health professionals’ perspectives. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008 Dec;45(12):1742–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams AF, Manias E, Walker R. The role of irrational thought in medicine adherence: people with diabetic kidney disease. J Adv Nurs. 2009 Aug 7; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devraj R, Gordon EJ. Health literacy and kidney disease: toward a new line of research. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 May;53(5):884–889. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007 Sep-Oct;31 (Suppl 1):S19–26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrity TF. Medical compliance and the clinician-patient relationship: a review. Soc Sci Med E. 1981 Aug;15(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/0271-5384(81)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med. 1992 Mar;34(5):507–513. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.