Abstract

Background

The objective of this study is to conduct a pooled analysis of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) colon trials involving surgery and surgery plus 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (5-FU/LV) to compare survival and establish a baseline from which to evaluate future studies.

Methods

All patients enrolled in NSABP adjuvant trials C-01 through C-05 with stage II and III disease who were treated with surgery or with surgery plus 5-FU/LV were examined for overall survival (OS), disease free survival (DFS), and recurrence free interval (RFI). Time-to-event by treatment group was examined using adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates and multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Results

There were 2,966 eligible patients: 693 (23%) surgery and 2,273 (77%) surgery plus 5-FU/LV; 1,255 (42%) stage II and 1,711 (58%) stage III. Age ≥ 60 years {hazard ratio (HR)=1.36, P<0.000], male gender (HR=1.20, P=0.0012), and more nodes positive or fewer nodes examined (P< 0.0001) were associated with worse survival. At 5 years, the adjusted OS was 0.62 [confidence interval (CI)= 0.60-0.63] in the surgery group and 0.76 (CI= 0.74- 0.78) in the surgery plus 5-FU/LV group. Treatment with 5-FU/LV was associated with improved outcome compared with surgery: OS (HR=0.62, P<0.0001), DFS (HR=0.66, P<0.0001) and RFI (HR=0.64, P<0.0001). Improved OS with adjuvant treatment was seen in both stage II (HR=0.58, 95% CI=0.48-0.71) and stage III disease (HR=0.65, 95% CI=0.55-0.75).

Conclusions

This analysis demonstrates that treatment of colon cancer patients with 5-FU/LV following surgery provides benefit over surgery alone and can provide anticipated survival outcomes from which to compare modern adjuvant trials.

Keywords: Adjuvant chemotherapy, Colon cancer, 5-Fluorouracil and Leucovorin

Historically, colon cancer survival at 5 years for stage II (T 3 and 4, N0, M0) and III (T any, N positive, M0) cancer ranges between 30% and 60%.1-4 In a recent national report, we have seen a 25% (male) and 21% (female) reduction in death rate from 1990 to 2003 for colorectal cancer alone.1 We are making great strides at improving the colon cancer burden through improved screening and early detection, aggressive surgery for resectable disease, and effective chemotherapy for advanced disease. Adjuvant chemotherapy has evolved from minimally effective single agent therapy to modern multiple-agent therapy. Single agent 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (5-FU/LV) had an objective response rate of about 20%; unfortunately, response rates paralleled toxicity and limited its clinical utility.5 It was not until 5-FU modulators levamisole and leucovorin (LV) were added that positive trials began to emerge in the 1980s and 90s.6-8 Work by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) and Intergroup (INT), systematically tested numerous agents and combinations until 5-FU/LV emerged as the most effective and least toxic adjuvant agent.8,9 Adjuvant 5-FU/LV became the accepted standard for stage III disease and high risk stage II disease.10 Today, the combination of 5-FU/LV and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) has replaced 5-FU/LV as the accepted adjuvant standard for stage III and high risk stage II colon cancer.11 With the development of newer agents to include oxaliplatin, irinotecan, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) modulators, new combinations of drugs are now being studied in the adjuvant setting. It is unlikely that future randomized clinical trials (RCT) will ever include control arms such as surgery alone or even surgery plus 5-FU/LV. This analysis provides the observed long term survival of stage II and III colon cancer patients using surgery alone or surgery plus 5-FU/LV.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

All patients enrolled in NSABP adjuvant trials C-01 through C-05 with stage II and III disease who were treated with surgery alone or with surgery plus 5-FU/LV were included. Patients provided informed consent obtained at time of enrollment. Details of the different protocol regimens and dates of accrual are described in the original publications.7,8,12-14 Criteria for entry into these different trials remained closely preserved yet some minor differences exist. NSABP adjuvant trials C-01 through C-05 included: Stage II and III colon cancer, excluded stage I / IV, and excluded all forms of rectal cancer. Age criteria changed over time: C-01 less than 80 years, C-02 any age, C-03 and C-04 less than 71 years, and C-05 life expectancy greater than 10 years. In the C-02 trial, enrollment occurred before surgery. In the remaining trials enrollment and treatment could not be delayed beyond postoperative day 42. All resections had to be completed with curative intent and could include removal of adjacent organs but not metastatic disease. Free perforations were specifically excluded in all five trials, C-04 and C0-5 allowed contained perforations. NSABP Protocol C-0112 (accrual dates 1977 - 1983) compared adjuvant semustine (MeCCNU/lomustine), vincristine, and 5-FU (MOF regimen) with surgery alone. Protocol C-0213 (accrual dates 1984 - 1988) compared the perioperative administration of a portal venous infusion of 5-FU with surgery alone. Protocol C-037 (accrual dates 1987 - 1989) compared adjuvant 5-FU/LV with adjuvant MOF. Protocol C-048 (accrual dates 1989 - 1990) compared adjuvant 5-FU/LV with 5-FU and levamisole (LEV) and with the combination of 5-FU, LV, and LEV. Protocol C-0514 (accrual dates 1991 to 1994) compared 5-FU/LV to 5-FU/LV plus alpha-interferon. Note that in the C-05 adjuvant trial the duration of 5 FU/LV was shortened from 12 to 6 months. In these five trials there were 3,321 patients who were treated with surgery alone or surgery plus 5-FU/LV. There were 355 patients who were excluded based upon predetermined criteria, leaving a total of 2,966 patients available for the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of patients randomized and number of patients included in analysis by protocol and treatment group

| Category | All Patients | Surgery | Surgery + 5-FU/LV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-01 | C-02 | Total | C-03 | C-04 | C-05 | Total | ||

| Total randomized | 3,321 | 394 | 581 | 975 | 539 | 719 | 1,088 | 2,346 |

| Ineligible | 206 | 19 | 123 | 142 | 20 | 26 | 18 | 64 |

| No follow-up | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Stage I | 114 | 0 | 114 | 114 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unable to determine stage | 31 | 25 | 1 | 26 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Total included in analysis | 2,966 | 350 | 343 | 693 | 513 | 691 | 1,069 | 2,273 |

Patients included in this analysis were not randomized between surgery alone and surgery plus 5-FU/LV. Because the treatment comparison is not randomized, we controlled for the important prognostic factors of age, gender, race, and nodes positive/examined in all treatment comparisons. The surgery-alone patients were treated from 1977 to 1988 and the surgery plus 5-FU/LV patients were treated from 1987 to 1994. Although laparoscopic colon surgery was not explicitly prohibited in these adjuvant colon trials, no patients were enrolled who underwent laparoscopic surgical resection.

Three efficacy outcomes were assessed including: (1) overall survival (OS) defined as the time from surgery to death, (2) disease-free survival (DFS) defined as time from surgery to first recurrence, second primary cancer, or death and (3) recurrence-free interval (RFI) defined as the time from surgery to recurrence censoring for death. Median follow-up was 15 years for the surgery-alone group and 13 years for the 5FU/LV group. Each of these outcomes was censored at last follow-up in the absence of an event. For each outcome, Kaplan-Meier estimates adjusted for age at entry, race, gender, and nodes positive/examined were computed and plotted by treatment group. The method of Xie and Liu15 was used to adjust the Kaplan-Meier estimates for imbalance of covariates across treatments. Age was assessed as a dichotomized variable based on a cut-point of less than 60 years of age (< 60, 60+ years). Race was categorized into three groups, white, black and other. Nodes positive/examined used four categories (0 positive and 12+ examined, 0 positive and < 12 examined, 1-3 positive and any examined, 4+ pos. and any examined.). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard-regression adjusted for age, race, gender, and nodes positive/examined, was used to determine the hazard ratio (HR) for treatment, to test for a treatment effect and to formally test for an interaction between treatment and nodes positive/examined. P-values from the Wald test16 were used for these assessments of main effects, whereas the likelihood ratio statistic was used to determine the significance of the interaction term. For additional insight, adjusted Kaplan-Meier plots stratified by stage of disease were generated for each outcome. A two-sided P-value of 0.05 was the basis for determining statistical significance for all evaluations. To better understand the natural history of stage II and III colon cancer, we explored the timing of recurrent disease following surgical resection.

RESULTS

Of the 2,966 patients, 693 (23%) received surgery alone and 2,273 (77%) patients received surgery followed by 5-FU/LV. The distribution of patients by demographic characteristics and treatment group is shown in Table 2. Overall, 84.6% were white, 54.9% were male, 52.2% were above the age of 60 years, 20.0% are node negative with at least 12 nodes examined, 22.4% were node negative with fewer than12 nodes examined, 38.4% had 1-3 positive nodes, and 19.3% had at least 4 positive nodes. The two treatment groups were similar with respect to gender but significantly different with respect to the distribution of race, age and nodes positive/examined. The surgery plus 5-FU/LV group was younger than the surgery only group (49.0% over age 59 years at entry compared to 64.2%, P<0.0001) and had a distribution of nodes positive/examined with poorer prognosis (P<0.0001). The distribution of race differed between treatments (P=0.0002) with the surgery plus 5-FU/LV group having a higher proportion of white patients (86.0% compared to 79.7%) and a lower proportion of black patients (8.9% compared to 13.9%).

Table 2.

Percent distribution of patients included in analyses by characteristics and treatment group

| Characteristic | Surgery (N = 693) | Surgery + 5-FU/LV (N = 2,273) | Total (N = 2,966) | P– valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White | 79.7 | 86.0 | 84.6 | |

| Black | 13.9 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 0.0002 |

| Other | 6.5 | 5.1 | 5.4 | |

| Age group | ||||

| < 60 | 35.8 | 51.0 | 47.5 | |

| ≥ 60 | 64.2 | 49.0 | 52.5 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 44.0 | 45.4 | 45.1 | |

| Male | 56.0 | 54.6 | 54.9 | 0.5194 |

| Positive Nodes (Nodes Examined) | ||||

| 0 (12 +) | 25.11 | 18.39 | 20.0 | |

| 0 (< 12) | 25.83 | 21.29 | 22.4 | <0.0001 |

| 1-3 (any) | 34.63 | 39.6 | 38.4 | |

| 4 + (any) | 14.43 | 20.72 | 19.3 |

Chi-square test for treatment difference.

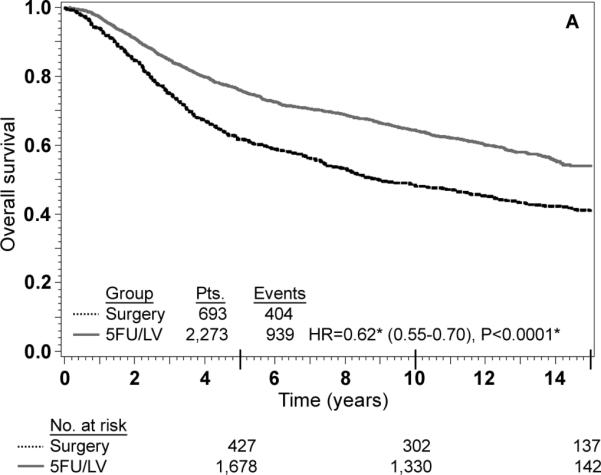

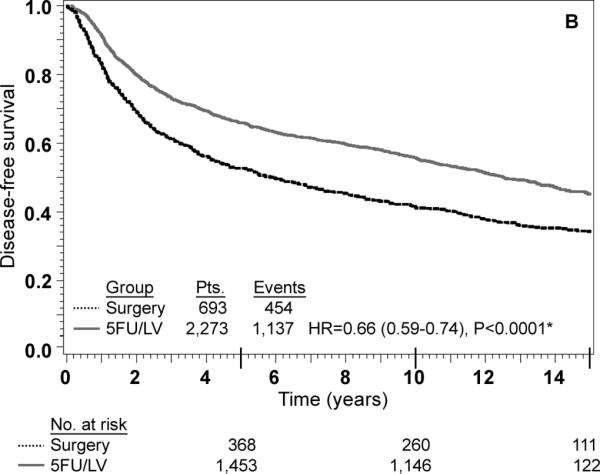

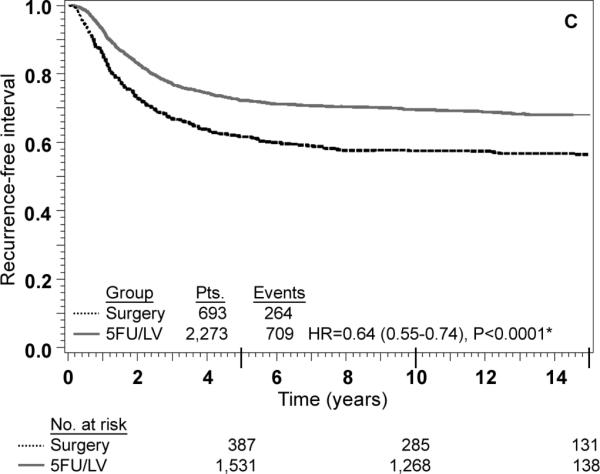

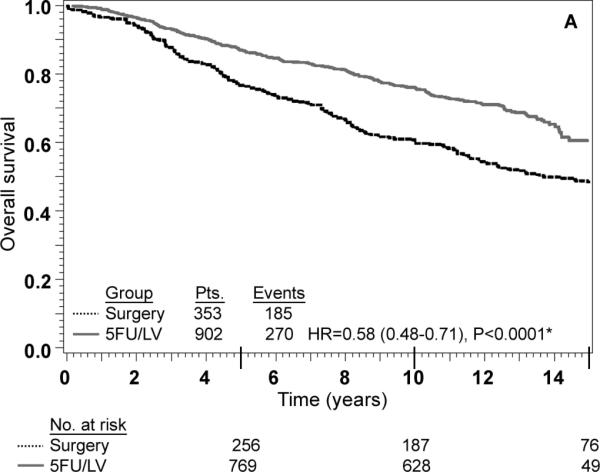

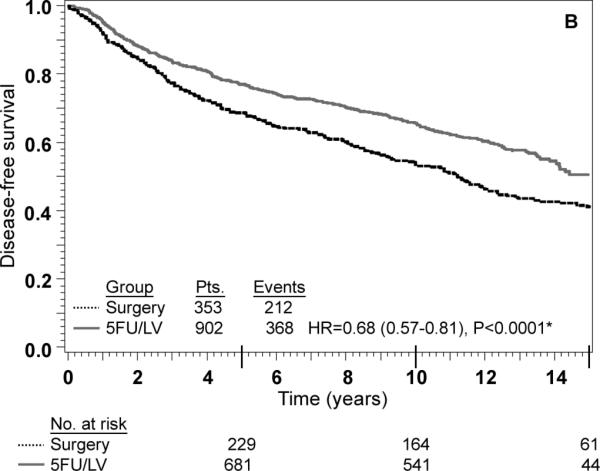

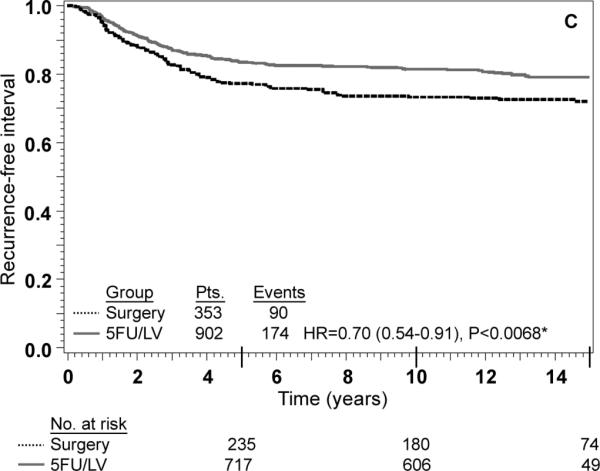

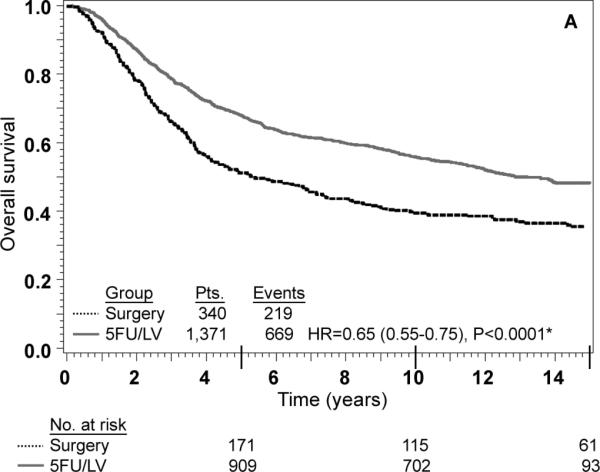

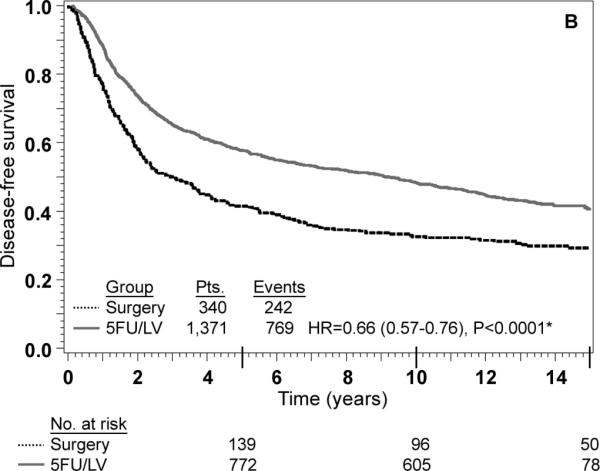

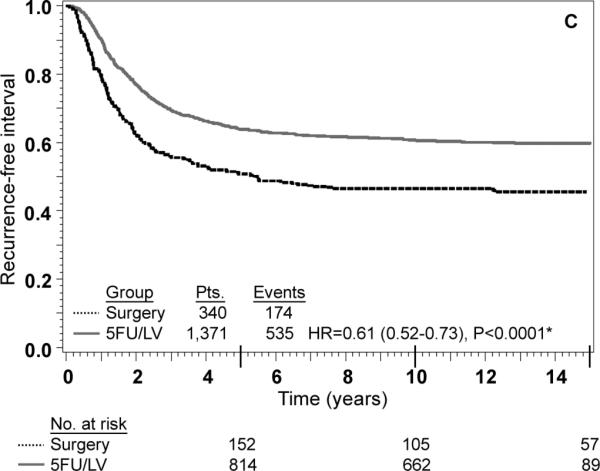

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS, DFS, and RFI by treatment are presented in Fig. 1. There is a highly statistically significant effect of treatment with 5-FU/LV evident for all three outcomes. Examining stage II and stage III disease separately demonstrates similar highly statistically significant effect of treatment as presented in Figs 2 and 3. The results of multivariate analysis using proportional-hazard modeling are presented in Table 3. Age ≥ 60 years (HR=1.36, P<0.0001) and male gender (HR=1.20, P=0.0012) were associated with worse OS. OS differed by race with poorer OS among blacks (P=0.0153) and by nodes positive/examined with poorer OS associated with fewer nodes examined or more positive nodes (P<0.0001). Treatment with 5-FU/LV was associated with improved OS compared to surgery only (HR=0.62, P<0.0001). Similar patterns of effects were found for these variables when considering DFS, except that race did not retain significance. For RFI, treatment and nodes positive/examined were the only parameters that were statistically significant, with improved outcome for those treated with 5-FU/LV (HR=0.64, P<0.0001) and poorer outcome for those with fewer nodes examined or more positive nodes (P<0.0001).

FIG. 1.

Stage II and III combined: adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) overall survival, (b) disease-free survival, and (c) recurrence-free interval. * From Cox model adjusted for age, gender, race, and nodes positive/examined

FIG. 2.

Stage II: adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) overall survival, (b) disease-free survival, and (c) recurrence-free interval. * From Cox model adjusted for age, gender, race, and nodes examined

FIG. 3.

Stage III: adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) overall survival, (b) disease-free survival, (c) recurrence-free interval. * From Cox model adjusted for age, gender, race, and nodes positive

Table 3.

Results of multivariable Cox-regression modeling of overall survival, disease-free survival and recurrence-free interval

| Characteristic | Overall Survival | Disease-free Survival | Recurrence-free Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age at entry | |||||||||

| < 60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.0896 | |||||

| ≥ 60 | 1.36 | 1.22 – 1.52 | <0.0001 | 1.30 | 1.17 – 1.43 | <0.0001 | 0.90 | 0.79 – 1.02 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male | 1.20 | 1.07 – 1.33 | 0.0012 | 1.19 | 1.08 – 1.31 | 0.0007 | 1.06 | 0.94 – 1.21 | 0.3507 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Black | 1.27 | 1.07 – 1.52 | .0153 | 1.14 | 0.96 – 1.34 | 1.13 | 0.92 – 1.39 | 0.4256 | |

| Other | 0.95 | 0.83 – 1.10 | 0.95 | 0.84 – 1.09 | 0.3096 | 0.99 | 0.84 – 1.17 | ||

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Surgery | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Surgery + 5-FU/LV | 0.62 | 0.55 - 0.70 | <0.0001 | 0.66 | 0.59 - 0.74 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.55 - 0.74 | <0.0001 |

| Positive Nodes (Nodes Examined) | |||||||||

| 0 (12 +) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0 (< 12) | 1.36 | 1.13-1.65 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | 1.11-1.55 | <0.0001 | 1.63 | 1.27-2.10 | <0.0001 |

| 1-3 (any) | 1.80 | 1.53-2.14 | 1.63 | 1.40-1.89 | 2.58 | 2.06-3.22 | |||

| 4 + (any) | 3.21 | 2.69-3.85 | 2.64 | 2.24-3.10 | 5.05 | 4.02-6.35 | |||

An interaction term between treatment and nodes positive/examined was added to each of the models shown in Table 3 as a formal test to determine if there was any evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of treatment by nodes positive/examined. The P-value for the test of interaction was not statistically significant for any of the three outcomes, indicating that the effect of 5-FU/LV was similar for patients in each of the four nodes positive/examined categories. Specifically, the P-value for interaction was 0.06 for OS, 0.32 for DFS and 0.36 for RFI. There was a trend towards significant interaction for OS (P=0.06) with 5-FU/LV providing a greater benefit in patients with better prognosis (HR for 5-FU/LV was 0.48 in node-negative patients with 12+ nodes examined, 0.62 in node-negative patients fewer than 12 nodes examined, 0.60 in patients with 1-3 positive nodes, and 0.80 in patients with 4 or more positive nodes). The lack of interaction is also evident from inspection of the adjusted Kaplan-Meier plots stratified by stage of disease. As anticipated, outcome is poorer for stage III patients than for stage II patients, but for all outcomes there is a statistically significant treatment effect within both stages of disease (Figs. 2 and 3). These findings must be approached with appropriate caution due to the nature of this pooled analysis (see “Discussion”).

To better understand the natural history of stage II and III colon cancer, we explored the timing of recurrent disease following surgical resection. Table 4 shows the timing of recurrent disease by year and by five-year increments for the surgery alone cohort as well as the cohort receiving 5-FU/LV. The risk for recurrence for the first 5 years was 23.1% for stage II disease and 48.3% for stage III disease in the surgery-alone cohort, and 16.4% for stage II disease and 36.4% for stage III disease in the 5-FU/LV cohort. Long-term follow up demonstrates minimal recurrence risk after the 10-year mark, regardless of treatment.

Table 4.

Recurrence patterna

| Surgery Alone (%) | Surgery + 5-FU/LV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage II | Stage III | Stage II | Stage III | |

| 1 year | 5.2 | 19.6 | 3.5 | 10.0 |

| 2 years | 6.5 | 21.4 | 5.7 | 14.7 |

| 3 years | 6.5 | 10.3 | 4.3 | 10.0 |

| 4 years | 4.5 | 5.2 | 2.0 | 4.6 |

| 5 years | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 3.5 |

| 6 years | 1.3 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Years 1-5 | 23.1 | 48.3 | 16.4 | 36.4 |

| Years 6-10 | 4.2 | 8.9 | 2.5 | 4.9 |

| Years 11-15 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.6 |

Probability of recurrence in the interval given the patient is alive and recurrence-free at the beginning of the interval

DISCUSSION

Recent developments in the treatment of colorectal cancer have dramatically changed the landscape from that of the 1970s and 1980s. New agents and new combinations are showing dramatic results.10,11 Our best combination regimens have now moved from the metastatic setting to the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting both in clinical trials and as standard of care. The most effective regimens are now advocated by national cancer guidelines, patterns of care, and patient demands. Due to these pressures it is inconceivable that future RCT studying adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer will ever include patients treated by surgery alone or even surgery followed by 5-FU/LV.

Many studies have been published to describe the natural history of stage II and III colon cancer. Many of these papers utilize data obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry,1 large institutional trials,2 and meta-analysis.3,4 Unfortunately, the results obtained in these studies come from heterogenous populations.1 Major variations within these studies include: treatment (surgery and chemotherapy), comorbidities, and follow up (screening testing and duration).1 Many of these pooled trials are derived from different countries using variable enrollment criteria.3,4 Despite these limitations, these studies have added to our understanding of this disease. To further build on this undertanding, the NSABP provides an alternative means of studying the natural history of this condition. The NSABP colon protocols can be used to examine stage II and III colon cancer survival treated under clearly defined entry, treatment, and follow up criteria.

In order to perform a pooled analysis, many assumptions must be met. The population must be consistent in terms of enrollment eligibility, treatment (both surgery and chemotherapy), and screening follow up. All patients in this pooled analysis were treated at NSABP-accredited facilities and accrued patients between (1977 and 1994). Entry criteria and defined follow-up standards were unchanged through all of these adjuvant colon trials. Surgical therapy for colon cancer has not been significantly modified in many decades. Surgical texts have advocated intraoperative staging, generous colonic margins (measured as 5 cm or greater), and regional lymphadenectomy. Recent surgical innovations such as sentinel lymph node staging and laparoscopic resections were not practiced in this timeframe. Preoperative chemoradiation and total mesorectal resection (TME) for rectal cancer did evolve in this era but would not have impacted colon cancer surgery. Preoperative staging with positron emission tomography (PET) scans was not utilized during this period (computed tomography and tumor markers have been available clinically for many years). We concluded that the NSABP colon cancer adjuvant trials would be appropriate for this type of pooled analysis.

Adjuvant therapy has clearly evolved as evidenced by the variety of drugs and delivery methods tested over the years. However, surgery alone and 5-FU/LV-based treatment arms have remained consistent throughout these five adjuvant trials. Temporal differences between these epochs, surgery alone (from 1977 to 1988), and the surgery plus 5-FU/LV (from 1987 to 1994) may account for some of the treatment effect attributed to 5-FU/LV in this analysis. Comparisons between equivalently treated arms have not demonstrated a temporal difference. Direct comparisons between the MOF-treated arms of C-01 and C-03 (accrual period ranged for 12 years, from 1977 to 1989) have been published by Wolmark et al.7 The three-year OS for MOF-treated patients in both C-01 and C-03 was 77% and 75%, respectively. The goal of this study was not to explore or discuss abandoned adjuvant regimens such as MOF. However, this does demonstrate consistent outcome over time and directly speaks against a temporal difference between these epochs.

This pooled analysis confirms that surgical therapy provides a meaningful and lasting cure to the majority of stage II and III colon cancer patients. The observed RFI at 10 years was 45% in the node-positive surgery-alone group. Regional node-positive disease cannot be misinterpreted as a sign of systemic disease. The surgical oncology community is currently debating the extent of lymphadenectomy (number of lymph nodes) that need to be resected in standard colon cancer surgery.17-19 Regardless of the exact number, this study should be used to emphasize that all regional metastatic disease should be resected with curative intent. Since there currently is no means of determining lymph node status prior to surgical therapy, standard complete lymphadenectomy must be advocated. The risks associated with a complete lymphadenectomy for colon cancer are minimal and can be accomplished using open and laparoscopic techniques. The benefits of sentinel node technology for axillary and inguinal lymphatic staging have shown promise in other disease states. How they can and should impact upon colon cancer treatment remains unknown. The surgical lymphadenectomy provides clear therapeutic benefit in node-positive colon cancer and we should resist the temptation to think of it as a staging procedure. It is unlikely that any modern adjuvant therapy will replace an adequate lymphadenectomy.

Numerous studies have supported the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer based upon sound RCT results.2-4 This study demonstrates a significant improvement in all efficacy measures (OS, DFS, and RFI) tested for stage III disease as demonstrated in Fig. 3. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II disease is more controversial and is debated in the oncology community.3,4,20,21 Much of the data regarding stage II disease suffers from inadequate numbers of randomized stage II patients in large cooperative groups. The Intergroup trial INT-0035 has reported the results of 318 eligible stage II patients and shown no survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.6 This trial studied patients with high risk stage II disease: obstruction 15-18% of patients, adherence to adjacent organs 11-16% of patients and perforation 6% of patients. Regional peritoneal implants were present in 3% of patients observation and 4% of patients treatment arms. NSABP enrolled a lower-risk stage II population (75% without any high-risk characteristics).21 Furthermore, stage distribution among different cooperative groups varies widely. The current NSABP pooled analysis contained 42% stage II and 58% stage III patients compared with INT-0035 with 26% stage II and 74% stage III.6 Due to the inadequate numbers of stage II cancers enrolled in RCT and preferential enrollment of higher-risk stage II patients, it is likely that this controversy will persist.

The recently published QUASAR trial enrolled 2,291 stage II colon cancer patients and concluded that adjuvant chemotherapy was well tolerated and effective. Relative risk of recurrence at 2 years was 0.71 (P=0.01) and mortality was 0.84 (P=0.046) in favor of adjuvant chemotherapy.22 In this NSABP analysis, we examined 1,255 patients with stage II disease and demonstrated a benefit of adjuvant therapy (5-FU/LV). The observed benefits seen in the treated cohort of stage II patients far exceeded those seen in the QUASAR clinical trials. This larger-than-expected difference may be due to differences in patient selection (high/low risk), temporal differences or limitations inherent to the pooled analysis method. The nonrandomized nature of this control versus 5-FU/LV comparison is a fundamental limitation that can be only partially addressed by multivariate modeling. Until future RCT can clarify the clinical benefit of modern adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer, the NSABP will continue to scientifically study this critical question.

Understanding the timing of recurrent disease is critical when making screening recommendations and guidelines. Based upon the patterns of recurrence seen in this analysis it is clear that all screening efforts should be directed toward the critical first 5 years (Table 4). These conclusions support those by Sargent23 et al in a recent pooled analysis of the Adjuvant Colon Cancer Endpoint (ACCENT) Group. In light of more effective systemic control, what will be the role and timing of surgical and systemic therapy for recurrent disease? Will recurrences be noted after the 5-year mark if modern adjuvant therapy proves more effective? Follow up recommendations need to be re-examined.

Current chemotherapy provides a meaningful survival advantage to patients with stage IV colon cancer. Unfortunately, these agents have not altered the ultimate outcome in stage IV disease. Eradication, through surgical resection or ablation of microscopic residual disease is still required.24 This stands in direct contrast to the results presented here: 5-FU/LV is associated with a measurable survival advantage (approximately 15% for stage III) lasting 10 to 15 years following surgery. This may represent effective treatment of “unestablished” micrometastatic disease rather than early treatment of unrecognized stage IV disease.

In conclusion, this analysis provides the observed survival outcome for resected colon cancer patients examining primary treatment modalities utilized in the 1970s through the 1990s. Two messages should be learned from these results. First, all gross disease and all regional lymph nodes at risk for metastatic disease must be surgically resected because surgery alone can cure the majority of stage II and III colon cancer patients. The incremental benefits of adjuvant therapy are unlikely ever to match these surgical results. Second, we should continue to study the long-term effects of adjuvant therapy in both stage II and III disease. Important questions remain. How do the results of 5-FU/LV therapy compare with the modern agents being examined today? For the assumed incremental benefit, what will be the added costs and toxicities? Identification of the highest-risk subset for adjuvant therapy still needs to be improved. These results can be used to provide comparison survival outcomes from which to compare modern adjuvant trials. Our future tasks must be to maximize the utilization of both surgical and adjuvant therapy while designing new clinical trials to improve on these results.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by: Public Health Service grants U10-CA-12027, U10-CA-69651, U10-CA-37377, and U10-CA-69974, from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: NSABP C-01: NCT00427570; NSABP C-02: NCT00427310; NSABP C-03: PDQ: NSABP C-03; NSABP C-04: NCT00425152; NSABP C-05: PDQ: NSABP C-05

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. Epub 2008 Feb 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Fluorouracil plus levamisole as effective adjuvant therapy after resection of stage III colon carcinoma: a final report. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:321–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-5-199503010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargent DJ, Patiyil S, Yothers G, et al. End points for colon cancer adjuvant trials: observations and recommendations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients enrolled onto 18 randomized trials from the ACCENT Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4569–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1797–806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.059. Epub 2004 Apr 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidelberger C, Chaudhuri NK, Danneberg P, et al. Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds. Nature. 1957;30:663–6. doi: 10.1038/179663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Intergroup study of fluorouracil plus levamisole as adjuvant therapy for stage II/Dukes’ B2 colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2936–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Fisher B, et al. The benefit of leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil as postoperative Adjuvant therapy for primary colon cancer: results from NSABP Protocol C-03. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1879–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Mamounas E, et al. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes’ B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3553–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller DG, Lefkopoulou M, Macdonald JS, Mayer RS. Some considerations concerning the dose and schedule of 5FU and leucovorin: toxicities of two dose schedules from the intergroup colon adjuvant trial (INT-0089). Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;339:51–4. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2488-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macdonald JS. Adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47:243–56. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.47.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2343–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolmark N, Fisher B, Rockette H, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or BCG for colon cancer: results from NSABP protocol C-01. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:30–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Wickerham DL, et al. Adjuvant therapy of Dukes’ A, B, and C adenocarcinoma of the colon with portal-vein fluorouracil hepatic infusion: preliminary results of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol C-02. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1466–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.9.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolmark N, Bryant J, Smith R, et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without interferon alfa-2a in colon carcinoma: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-05. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1810–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.23.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med. 2005;24:3089–110. doi: 10.1002/sim.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin DY, Wei LJ. Robust inference for the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Kulaylat M, Rockette H, et al. Should total number of lymph nodes be used as a quality of care measure for stage III colon cancer? Ann Surg. 2009;249:559–63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318197f2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsikitis VL, Larson DL, Wolff BG, et al. Survival in stage III colon cancer is independent of the total number of lymph nodes retrieved. J Am College Surg. 2008;1:42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namm J, Ng M, Roy-Chowdhury S, Morgan JW, Lum SS, Wong JH. Quantitating the impact of stage migration on staging accuracy in colorectal cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;207:882–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle CC, Weiser MR, Ter Veer A, et al. Effect of lymph node retrieval rates on the utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:525–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mamounas E, Wieand S, Wolmark N, et al. Comparative efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Dukes’ B versus Dukes’ C colon cancer: results from four National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Adjuvant Studies (C-01, C-02, C-03, and C-04.) J Clin Oncol. 1999;7:1349–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quasar Collaborative Group. Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, Hills RK, Williams NS, Kerr DJ. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. 2007;370:2020–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sargent D, Sobrero A, Grothey A, O'Connell MJ, et al. Evidence for cure by adjuvant therapy in colon cancer: observations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:872–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adam R, Wicherts DA, de Haas RJ, et al. Complete pathologic response after preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: myth or reality? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1635–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]