Abstract

Motivation: Recent genomic studies have confirmed that cancer is of utmost phenotypical complexity, varying greatly in terms of subtypes and evolutionary stages. When classifying cancer tissue samples, subnetwork marker approaches have proven to be superior over single gene marker approaches, most importantly in cross-platform evaluation schemes. However, prior subnetwork-based approaches do not explicitly address the great phenotypical complexity of cancer.

Results: We explicitly address this and employ density-constrained biclustering to compute subnetwork markers, which reflect pathways being dysregulated in many, but not necessarily all samples under consideration. In breast cancer we achieve substantial improvements over all cross-platform applicable approaches when predicting TP53 mutation status in a well-established non-cross-platform setting. In colon cancer, we raise prediction accuracy in the most difficult instances from 87% to 93% for cancer versus non−cancer and from 83% to (astonishing) 92%, for with versus without liver metastasis, in well-established cross-platform evaluation schemes.

Availability: Software is available on request.

Contact: alexsch@math.berkeley.edu; ester@cs.sfu.ca

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Throughout the decades, cancer has been not only a most daunting, but also most intriguing disease to study. It is daunting since it persistently keeps escaping our deeper understanding while, at the same time, it is the reason for as many as 13% of human deaths worldwide. As a mere object to study, however, it is also most fascinating since it is crucially entangled with the mechanisms which are responsible for cellular welfare. Clearly, a deeper understanding of cancer would shed light on a wealth of aspects being essential for eukaryotic life.

In the meantime, there has been abundant evidence that cancer is phenotypically of utmost complexity. On one hand, most recent studies on cancer genomes reveal the extent of DNA damage (Beroukhim et al., 2010; Campbell et al., 2008; Hampton et al., 2009)—numbers of copy number variations and genomic rearrangements are so large that one can hardly believe that cancer cells are viable at all. On the other hand, it has been well-known that cancer cells evolve (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990). Starting out as healthy human cells they gradually undergo phenotypical changes through accumulating genomic alterations first transforming into malignant and finally into metastatic and/or therapy-resistant specimens. In conclusion, it is safe to assume that no two cancer genomes of two different people, at least at first glance, even look similar and even one person's cancer is made up by a variety of different cell types belonging to the different stages of cancer evolution.

Nevertheless, it is possible to classify cancer, to identify subtypes common to many people and also to cure or at least to slow down progression in many patients by means of identical therapy protocols. Therefore, one of the most driving questions in most recent research is to reveal the genetic alterations common to all cancer cells within and also across its many subtypes.

To successfully classify cancer tissue samples one needs reliable criteria on the biomolecular level that is disease markers. While markers serve as indicators of cancer and/or its subtypes in the first place they can also point at the crucial processes and perturbations giving rise to cancer such that it may be worth studying them beyond their role as classification features.

In a seminal study, Golub et al. (1999) successfully identified 50 differentially expressed genes which can successfully distinguish between two leukemia subtypes. Similar approaches determined differentially expressed genes for B-cell lymphoma (Alizadeh et al., 2000), breast (van de Vijver et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2005) and lung cancer (Beer et al., 2002), which served as monogenic, that is single gene markers (SGMs).

However, SGM sets determined based on differential expression varied considerably when inferring them from different platforms such that they were useless in cross-platform studies, hence of no universal applicability (Ein-Dor et al., 2005, 2006). Chuang et al. (2007) finally pointed out that multigenic markers were able to address this issue. Multigenic markers consist of several differentially expressed genes which also form a connected region in protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks and proved to be more stable predictors in cross-platform evaluation schemes. Similar approaches followed (Chowdhury and Koyutürk, 2010; Ulitsky et al., 2008) where only the latter focuses on cancer. While the primary purpose of subnetwork marker computation is to provide cross-platform-applicable indicators of disease, they can also yield further insights on cancer because they usually reflect (parts of) dysregulated pathways.

Inference of subnetwork markers comes with most demanding computational and combinatorial challenges due to the tremendous number of plausible subnetwork patterns to be examined. Here, we aimed at solving a combinatorial problem which particularly addresses that the same cancer can come in many different subtypes and stages of progression which cannot necessarily distinguished by visual inspection (e.g. Rosenwald et al., 2002). Namely, we addressed that pathways which are dysregulated in cancer can show in many, but not all cancer patients. This reflects that cancer is a most diverse disease which, nonetheless, can be classified—there are phenomena which are common to many (but not necessarily all) different specimens.

Summary of contributions: We present a computational strategy to solve this combinatorial search problem and show that applying it results in exhaustive enumeration of subnetwork biclusters that is combinations of gene and sample clusters where participating genes form dense, connected subgraphs in a PPI network. Hence, our markers can be taken as (fractions of) pathways which are dysregulated in sufficiently many, but not necessarily all cancer (subtype) samples. To serve the purposes of a fair benchmarking competition we first perform cross-platform classification on colon cancer datasets as described in the state-of-the-art approach of Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) and outperform the prior approaches partly by raising accuracy by a relative increase of nearly 50%. Second, we perform cross-validation (within the same platform) experiments on breast cancer as described in Miller et al. (2005) and outperform all approaches which yield universal, platform-independent markers. In both cases, we analyze the subnetworks associated with our top-ranked markers.

2 APPROACH

Our approach differs from the previous approaches predominantly in terms of how subnetwork markers are computed. To subsequently classify, well-established techniques such as support vector machines (Schölkopf and Smola, 2002) were used in all related studies. The general idea behind computation of subnetwork markers is to search for combinations of genes which

are ‘sufficiently’ differentially expressed in the cancer tissue samples from the gene expression training data and

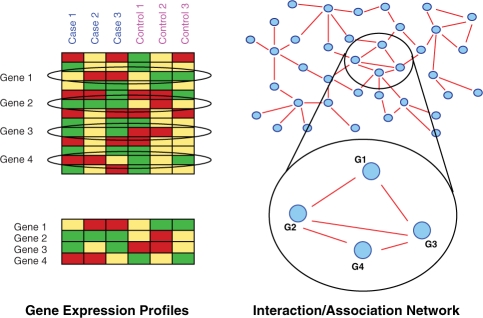

form a connected pattern in the PPI network. See Figure. 1 for a generic example.

Prior work: the idea which is common to the majority of prior approaches is to aim at inferring genes g whose gene expression profiles E(g) ∈ ℝK (where K is the number of samples) share large mutual information with the phenotype profile P = (1,…,1, 2,…, 2) ∈ {1, 2}K where Pk = 1, 2 indicates whether sample k belongs to the phenotype (cancer/cancer subtype) or not where large mutual information roughly translates to strong correlation. Correspondingly, SGMs are selected as single genes g where E(g) has large mutual information whereas subnetwork markers, in previous approaches, were chosen such that the average gene expression profile of all genes participating in the marker shares large mutual information with P. We refer the reader to the Supplementary Materials for more details and also for a more detailed description of the subnetwork marker approaches of Chuang et al. (2007) and Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) which serve as benchmarking partners. None of the approaches from above follows the idea that certain subnetworks might be dysregulated in some, but not all samples. Our approach specifically addresses this point.

Fig. 1.

When determining subnetwork markers one aims at finding groups of genes where genes have expression profiles which are different in cancer and control and also form a connected pattern in an accompanying PPI network. Here, genes 1, 2, 3 and 4 comply with these criteria.

Our method: three things are substantially different:

The PPI networks we employ are confidence scored (Jensen et al., 2009).

Our subnetworks not only need to be connected, but also need to contain a sufficient amount of edge weight (= confidence scores).

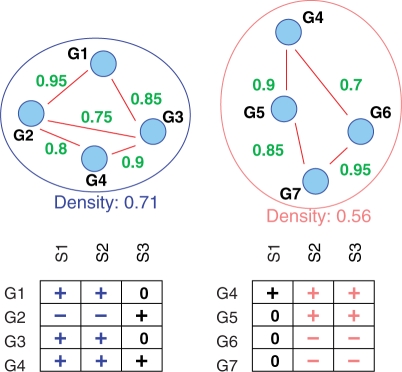

In our case, all genes in a subnetwork need to be dysregulated in a subset of patients of size at least L, but not necessarily in all patients. In other words, the genes of the subnetwork and the L cancer samples in which the subnetwork, as a whole, is dysregulated form a bicluster. See Figure 2 for two examples of subnetwork markers and Section 3 for precise definitions.

Fig. 2.

Two density-constrained biclusters (see Section 3.1 for the definition of density) where genes are differentially, either consistently over- (+) or under- (−) expressed in a subset of size at least 2 of cancer samples. 0 is for no differential expression.

The advantage of confidence-scored physical PPI networks is that each detected physical interaction is rated by the likelihood that the interaction does play a cellular role and is not merely an experimental artifact. As a consequence, dense connectivity can be interpreted as that the genes in the subnetwork establish a cellular functional element through physically interacting with each other which comes from accumulating high confidence scores within the subnetwork (Jensen et al., 2009). In fact, many markers we compute are enriched with Gene Ontology terms whereas this is not as obvious for the previous approaches (Section 4). The third point finally reflects the discussion from above: unlike in the previous approaches, we would like to have markers apply as an entity for a sufficient amount but not necessarily all cancer samples.

Further related work: colorectal cancer is a most ubiquitous type of cancer which has been well studied (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990; Macdonald et al., 2004; Nibbe et al., 2010). Similarly, breast cancer has been received widespread attention. Apart from work cited above, see Gasco et al. (2002) for a review on pathways disturbed in breast cancer. See Section 4 for more related work. There have been many network approaches to search for interesting subnetwork patterns where participating genes are differentially expressed which, however, were not used in clinical settings. See Dittrich et al. (2008); Ideker et al. (2002) and Sharan et al. (2007) for most prominent approaches and a review and Xu et al. (2007) for a study on cancer differential co-expression networks. Density-constrained biclustering was originally discussed in binary edge-weight network settings (Colak, 2008; Moser et al., 2009). Here, we extend it to networks with edge weights and deliver the proof that the analogous search strategy applies. Note also (Georgii et al., 2009) where it is shown that, in weighted-edge networks, density is a loose antimonotone property (see definition below). Here, we generalize this showing this for density and connectivity in combination.

3 METHODS AND DATA

3.1 Notations, definitions and theorems

Let G = (V, E) be a network where the set of nodes V is identified with the genes, respectively, their associated proteins and an edge e = (u, v) indicates a potential physical PPI between the proteins associated with u, v ∈ V. We also have a weight function on the edges

where w(e) is the confidence score associated with edge e ∈ E. We recall that w(e) reflects our degree of belief that the physical PPI associated with e plays a functional cellular role. In order to have gene expression experiments included in our considerations we have a differential expression label function

which assigns a K-dimensional vector D(v) with entries + (overexpressed in cancer sample), − (underexpressed in cancer sample) and 0 (not differentially expressed in cancer sample) to each of the nodes where K is the number of cancer samples in the dataset. We denote the i-th entry of D(v) by D(v)i such that, for example, D(v)i = + means that gene v is overexpressed in cancer sample i. We then define:

- The density θ(G′) of a subnetwork G′ = (V′, E′) of G is

where

is the number of possible edges in G′.

is the number of possible edges in G′. - G′ is called α-dense if

where α ∈ [0, 1].

An α-dense, connected subnetwork G′ is called α-densely connected.

- A subset of genes V′ ⊂ V is called a differential L-bicluster if there is a subset {i1,…, iL} ⊂ {1,…, K} such that

for all v ∈ V′. That is each gene needs to be consistently differentially either over- or underexpressed in a subset of samples of size at least L. As an example, see Figure 2. There, genes G1, G2, G3, G4 (resp. G4, G5, G6, G7) form a differential bicluster with respect to the samples S1, S2 (resp. S2, S3).

An α-densely connected subnetwork G′ = (V′, E′) where V′ forms a differential L-bicluster is called a α-density-constrained L-bicluster.

We would like to devise a strategy by which to tractably mine all α-density-constrained L-biclusters. To outline our strategy we define:

A graph property is called strong antimonotone if in each graph of size n with the property every induced subgraph of size n − 1 has the property.

A graph property is called loose antimonotone if in each graph of size n with the property there is an induced subgraph of size n − 1 with the property.

Strong antimonotonicity implies loose antimonotonicity. As a simple example consider graphs where nodes are labeled by either red or blue color. Clearly, the property to have only red nodes is strong antimonotone: all subgraphs of a red graph are red. As a simple example for loose antimonotonicity consider paths: clearly, removing either the start or the end node results in another, shorter path. However, not every node can be removed—removing internal nodes splits the path. Another loose antimonotone property on red–blue graphs is that at least half of the nodes are red. Removing blue nodes works while removing red nodes does not necessarily result in a predominantly red colored graph. We make a few observations:

Combining a strong antimonotone with a loose antimonotone results in a loose antimonotone property. For example, in red–blue colored graphs, to be a red path is a loose antimonotone property.

Combining a loose antimonotone with a loose antimonotone property does not necessarily result in a loose antimonotone property. Consider the property (on red–blue colored graphs) to be a path with at least half of the nodes being red. To see that this is not loose antimonotone take a path of length 4 where both start and end node are colored red whereas the two internal nodes are colored blue. Removal of none of the nodes results in a predominantly red colored path.

In our setting, we obtain the following results where G − v is the subgraph of G which results from removing v and all edges incident to v:

Theorem 3.1. —

Every subgraph of a differential bicluster of degree at least L is a differential bicluster of degree at least L.

In every connected, weighted-edge graph G = (V, E, w) where θ(G) = α ≥ 1/2 there is a node v ∈ V such that G − v is connected and θ(G − v)≥α.

In every (α, L)-density-constrained bicluster G=(V, E) where 0.5 ≤ α ≤ 1.0 there is a node v ∈ V such that G − v is a α-density-constrained L-bicluster.

In other words, Theorem 3.1 establishes that to be a differential L-bicluster is strong antimonotone whereas to be an α-densely connected graph or to be a density-constrained bicluster are both loose antimonotone.

Proof. —

Strong antimonoticity of differential biclusters is easy. If G is differentially expressed in L samples then so is any subgraph of G.

Loose antimonotonicity of dense connectivity is a little more tricky. The arguments proceed in a similar way, while are not completely analogous to those in Colak (2008) and Moser et al. (2009). Due to space constraints, we have deferred the proof to the Supplementary Materials.

Since (see above) combining a strong antimonotone with a loose antimonotone property results in a loose antimonotone property, (3) follows immediately from (1) and (2). ▪

3.2 Algorithms

3.2.1 Algorithmic mining strategy

Theorem 3.1 supports a search strategy which is based on the loose antimonotonicity of density-constrained biclusters and is completely analogous to that of Moser et al. (2009) for the case 0.5 ≤ α ≤ 1.0 which was also employed in Colak et al. (2009). This strategy will yield all α-density-constrained L-biclusters U for α ∈ [0.5, 1.0] which are maximal in the sense that there is no proper α-density-constrained L-bicluster which contains U as an induced subgraph. This strategy applies for all loose antimonotone properties and therefore applies when mining α-density-constrained L-biclusters. Subnetworks are screened in a breadth-first fashion by starting with subnetworks of size 2 and subsequently neglecting subnetworks of size n ≥ 3 which do not contain any density-constrained bicluster of size n − 1. Loose antimonotonicity guarantees that subnetworks of size n cannot be density-constrained biclusters if not containing a density-constrained bicluster of size n − 1. As was also demonstrated in Colak (2008); Colak et al. (2010) and Moser et al. (2009) this results in a tractable strategy when combining PPI network with gene expression data. Here, all maximal density-constrained biclusters were computed in runtimes of at most 2–3 min on an ordinary personal computer.

3.2.2 Ranking procedure

The resulting set of all density-constrained biclusters is ranked with respect to statistical significance. We randomly sampled 105 connected subnetworks and determined the P-value of a density-constrained L-bicluster G′ as the fraction of randomly sampled subnetworks H with θ(H)≥θ(G′) and H being consistently dysregulated in at least L samples. We select markers top-down from this P-value based-ranking list while discarding biclusters where more than half of the genes are already contained in previously selected markers. For experiments on breast cancer, we furthermore reranked our 50 most significantly dense modules by applying the information-theoretic criteria as described for the approaches which were employed for benchmarking. See Supplementary Materials for details.

3.3 Datasets and classification schemes

3.3.1 Network data

We downloaded the licensed PPI network from the STRING database, version 8.1 (Jensen et al., 2009). STRING provides several variants of association network where edges come with a confidence score. Networks can vary in terms of number of proteins, edge content and confidence scores attached to the edges. In our case, the network consisted of 9927 proteins and 62 539 edges. Edges have a positive confidence score in case that there is evidence that the two proteins in question physically interact within a cellular context. We opted to exclusively treat physical interactions since comparison partners only considered (ordinary) physical PPI networks. Note that their methods do not allow to make use of edge weights. For these methods unweighted PPI network data as described in Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) was used.

3.3.2 Colon cancer gene expression data

In analogy to Chowdhury and Koyutürk's (2010) study, we treated the microarray datasets with the accession numbers GSE8671, GSE10950 and GSE6988 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (Barrett et al., 2009). GSE8671 contains 8987 gene expression profiles across 32 prospectively collected adenomas with those of normal mucosa from the same individuals (Sabates-Bellver et al., 2007). GSE10950 contains 18 171 gene expression profiles across normal and tumor pairs (Jiang et al., 2008). GSE6988 contains 17 104 gene expression profiles for 25 normal colorectal mucosa, 27 primary colorectal tumors, 13 normal liver, 27 liver metastasis and 20 primary colorectal tumors without liver metastasis (Ki et al., 2007).

3.3.3 Breast cancer gene expression data

We considered the gene expression dataset GSE3494 treated in Miller et al. (2005) along with all available additional information. Experiments performed in Miller et al. (2005) aim at predicting TP53 mutation status, tumor grade and survival time. Therefore, they first identify platform-specific (Affymetrix U133 A and B) probes as being correlated with TP53 mutation and estrogen receptor status as well as tumor grade, using multivariate linear regression from their own data. Subsequently, they select 32 such platform-specific probes as being the features which yield best accuracy when performing cross-validation on their own data. This means that accuracy values cannot be taken as unbiased results since feature selection is based on the outcome of the cross-validation.

3.3.4 Differential expression

For the colon cancer datasets, GSE8671 and GSE10950, we determine differential expression as described in Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010). We first normalize expression values for each gene v individually. Let E(v, j) be the resulting normalized expression value for gene v in sample j. We then determine the top 10% of the values E(v, j) in each sample j and declare them ‘overexpressed’. In both datasets samples come in pairs cancer versus healthy. Let j1 be the cancer and j2 be healthy sample for one patient l. We then put D(v)l=+, resp. D(v)l = − if v is overexpressed in j1, but not in j2, resp. the other way round.

In the breast cancer dataset GSE3494 (see below), we determine a normal distribution for all values and normalize the entire data accordingly. For an arbitrary sample l, let E(v, l) be the corresponding normalized value. Subsequently, D(v)l = + for a sample l if E(v, l) is among the top 5%, resp. D(v)l = − if E(v, l) is among the lowest 5%.

3.3.5 Classification

It is performed by a support vector machine approach implementing a linear kernel using Matlab's svmclassify. For colon cancer versus healthy classification, the training data are identical with that used for marker computation (i.e. either GSE8671 or GSE10950). For colon cancer with versus without liver metastasis, markers are computed using GSE8671 or GSE10950 and classification is performed by leave-one-out cross-validation in GSE6988. This coincides with the procedures described in Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010). For breast cancer TP53 wildtype versus mutant markers are computed using GSE3494 and classification is performed by leave-one-out cross-validation in the same dataset. The breast cancer classification scheme is the only non-cross-platform experiment. In colon cancer data used for marker computation and classification test data come from two different platforms. For feature space construction, we choose the best K markers to obtain a feature space of dimension K. Each sample j is transformed into a K-dimensional vector A(j)∈ℝK where the entries A(j)k for each marker k are A(j)k≔∑vE(v, j)/K where v ranges over all genes v contained in the subnetwork associated with marker k. In other words, each sample j becomes a point A(j) in the K-dimensional marker feature space ℝK.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Colon cancer

Overall, we used Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) as a guideline and followed their workflow for cross-platform predictions.

4.1.1 Marker computation

We computed and subsequently ranked subnetwork markers as described in Section 3 both using GSE8671 (parameter choices: α = 0.5, L = 3) and GSE10950 (α = 0.5, L = 2). Parameters were chosen as non-restrictive as possible such that the total number of subnetwork markers did not exceed 1000. Throughout this section, our method is referred to as weighted density-constrained biclustering (wDCB). Since GSE6988 does not contain paired cancer/control samples one cannot compute markers as described in Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) We also computed and ranked subnetwork markers [greedy mutual information (GMI)] as described in Chuang et al. (2007), SGM as described in Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) and were provided with subnetwork markers by Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) extracted from GSE8671, accordingly ranked (NETCOVER = NC). However, neither subnetwork markers from GSE10950 nor the implementation of the NetCover (NC) algorithm were publicly available at the time when experiments were performed. In the following, values for Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010) referring to subnetwork markers extracted from GSE10950 are adopted from their article.

4.1.2 Classification

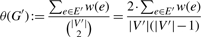

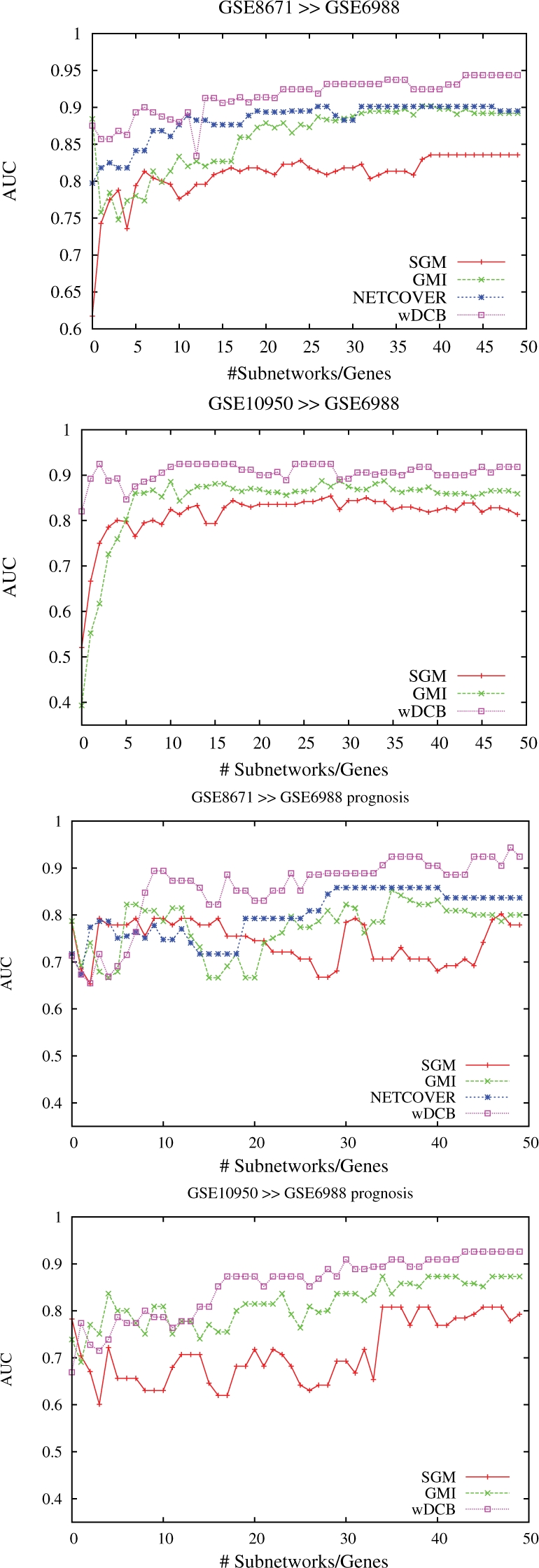

It was performed as described in Section 3, using support vector machines for both GMI and NC as was evaluated as yielding maximal predictive power in both cases (Chowdhury and Koyutürk, 2010). Predictions refer to predicting cancer versus healthy tissue, resp. liver metastasis versus non-liver metastasis (henceforth referred to as ‘Prognosis’) in GSE6988 using the markers from GSE8671 and GSE10950. Note that we cannot display certain values referring to markers from GSE10950 for NC since we were not provided with the corresponding subnetworks nor the software. In the following, positives (= P) and negatives (= N) are cancer and healthy resp. liver metastasis and non-liver-metastasis tissue samples such that true resp. false positives resp. negatives (= TP, FP, TN, FN) are correctly resp. misclassified cancer/metastasis resp. healthy/non-metastasis samples. Figure 3 displays AUC (area under the precision–recall curve) which is computed as the arithmetic average of precision (= TP/(TP + FP)) and recall (=TP/(TP + FN)) for different choices of subnetwork markers and the two prediction tasks where markers are chosen according to the corresponding rankings. Note that values for NC using markers from GSE10950 are missing due to the above-mentioned reasons. In Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010), an average AUC of 0.86 is reported for prediction of GSE6988 (wDCB: 0.91, see Table 1 in the Supplementary Material for more information). See also the Supplementary, Figure 2 for plots referring to making predictions in GSE8671 from GSE10950 and vice versa; the corresponding results are rather negligible–-every competitor achieves AUC/accuracy close to 100%. We recall that GSE6988 is the most difficult dataset, due to size (123 samples) and comprehensiveness in terms of subtypes and stages of progression.

Fig. 3.

Colon cancer: AUC versus numbers of subnetwork markers using markers extracted from GSE8671 and GSE10950 for cancer versus non-cancer (upper two plots) and liver metastasis versus non-metastasis (lower two plots) prediction in GSE6988.

Table 1.

Accuracy for varying numbers K of markers relating to experiments on colon cancer

| K |

SGM |

GMI |

NC |

wDCB |

SGM |

GMI |

NC |

wDCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8671→6988 |

10 950→6988 |

|||||||

| 1 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.63 | 0.37 | N/A | 0.77 |

| 5 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.68 | N/A | 0.86 |

| 10 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.81 | N/A | 0.88 |

| 20 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.83 | N/A | 0.89 |

| 30 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.85 | N/A | 0.85 |

| 40 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.84 | N/A | 0.89 |

| 50 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.82 | N/A | 0.89 |

| 8671→6988, Prognosis |

10 950→6988, Prognosis |

|||||||

| 1 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.68 | N/A | 0.47 |

| 5 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.81 | N/A | 0.68 |

| 10 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.57 | 0.77 | N/A | 0.74 |

| 20 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.79 | N/A | 0.85 |

| 30 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.81 | N/A | 0.85 |

| 40 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.85 | N/A | 0.89 |

| 50 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.85 | N/A | 0.91 |

NC = NETCOVER. Boldface: top score. NC 10 950 subnetworks are not available. See Supplementary Material for sensitivity and specificity values.

We also display Accuracy (= (TP + TN)/(P + N)) values in Table 1 for predictions using GSE8671 markers, which are available for all competitors. See also Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 for more values on cancer versus non-cancer including sensitivity (recall) and specificity (= TN/N) which translate to fractions of correctly predicted cancer resp. healthy samples. We do think that sensitivity/specificity/accuracy statistics make most sense. However, for fairness reasons, we followed the workflow scheme of Chowdhury and Koyutürk (2010), which is based on AUC. Overall, our method outperforms all competitors both when predicting cancer versus non-cancer and metastasis versus non-metatastis. In the latter case, when using subnetworks from GSE8671, the increase in accuracy from 83%, the best value obtained by the competitors, to 92%, obtained by our method wDCB is quite remarkable. Note that this is a relative increase of more than 50% (9% out of possible 17%) translating to > 50% less misclassified samples. In conclusion, our method proves best on a difficult colon cancer dataset in all categories tested, raising accuracy beyond 90% as the only method in three test cases.

4.2 Breast cancer

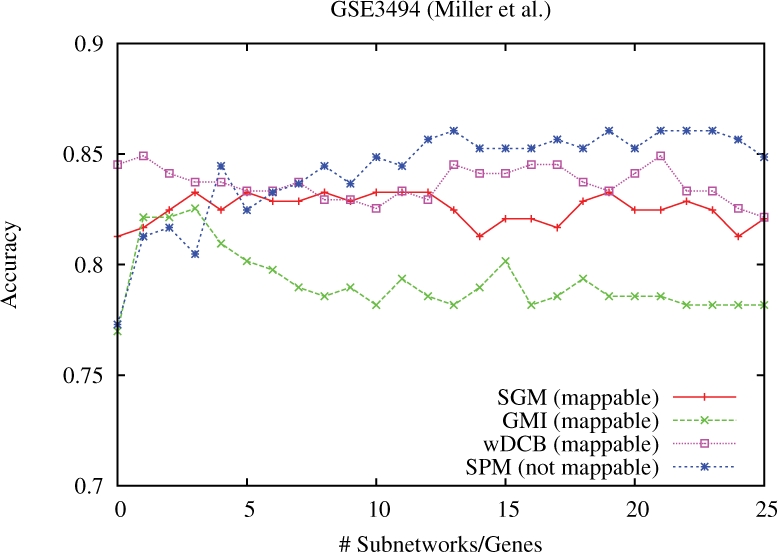

Here, we use Miller et al. (2005) as a guideline. We focus on TP53 mutation status and predict wildtype (wt) versus mutant (mt), a binary classification task. We first compute markers from GSE3494 and subsequently employ the suggested leave-one-out cross-validation scheme in the same dataset. As has been recently pointed out (Chuang et al., 2007; Ein-Dor et al., 2005, 2006) non-cross-platform evaluations (marker computation and classification are performed in the same dataset) come with two issues: first, they are biased toward markers which do not have to rely on mapping probes to well-established gene identifiers and second, SGMs traditionally ‘overperform’, i.e. when using them for classification on other platforms their predictive power tends to significantly decrease. We recall that cross-platform stability is a major source of motivation for subnetwork marker approaches. In the following we will distinguish between single probe markers (SPMs) that is a SGM approach making use of all probe data available in GSE3494 even if probes cannot be mapped (possibly reflecting non-coding RNA, etc.).1 SGMs, which is the equivalent of SPM using only mappable gene probes, GMI (Chuang et al., 2007) and our approach wDCB which both rely on mapping probes onto nodes in PPI networks.

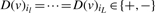

4.2.1 Marker computation and predictions

We computed markers for SPM, SGM, GMI and wDCB as described in Section 3. For wDCB, we used parameters α = 0.5, L = 5 again chosen as being most non-restrictive while keeping the computed numbers of subnetworks below 1000. We plotted accuracy versus different numbers of markers (Fig. 4) and observed that for more than 25 markers none of the methods achieved further improvements. The non-mappable SPM achieve maximum accuracy for numbers of markers between 5 and 25, whereas wDCB achieves best values for choosing only up to 5 top-ranked markers. Among the approaches generating universally mappable marker sets, wDCB performs best. Note that, as was reported in previous studies, it is reasonable to assume that the mappable SGM set SGM will suffer from decreased performance rates in cross-platform evaluations (Chuang et al., 2007; Ein-Dor et al., 2006) whereas such effects have not been reported for subnetwork marker approaches. We conclude that our approach wDCB comes is of substantial value also in breast cancer subtyping.

Fig. 4.

Breast cancer: accuracy versus numbers of subnetwork markers using markers extracted from GSE3494 for predicting TP53 mutation status (wildtype versus mutant) in GSE3494 (leave-one-out cross-validation).

4.3 Analysis of our top markers

4.3.1 Markers GSE8671, colon cancer

GO enrichment analysis of the 186 genes identified in the top subnetworks from GSE8671 revealed a significant role for genes involved in the biological processes of DNA replication, DNA metabolic process, DNA repair and cell cycle progression (Bonferonni corrected, P < 1e − 20). In particular tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, BRCA1 and mis-match repair genes MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 all well-characterized genes known to be involved in colon cancer tumorigenesis (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990) are featured in the top-ranked subnetworks. The top-ranked subnetwork contains TP53 and most of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex components, which are essential for replication of DNA during cell division. In particular MCM2 and MCM5, have been shown to be early markers for CRC (Burger, 2008) and overall almost all CRC display dysregulation of the TP53 pathway through mutations or other means of functional inactivation.

4.3.2 Markers GSE3494, breast cancer

Here we focused on the role of TP53, whose expression signature was used previously to classify prognostic classes in two breast cancer and one liver cancer cohorts with known TP53 status (Miller et al., 2005). We found similar enrichment of GO terms such as DNA replication, DNA metabolic process and cell cycle progression (Bonferonni corrected, P < 1e − 20) in the 174 genes identified in our top subnetworks used for classification of TP53 mutational status. Furthermore, the subnetworks identified for known TP53 status in breast cancer were comprised of many of the same genes identified in the colon cancer subnetwork analysis (65 genes in total, ∼35% overlap). Given the well-characterized role of dysregulated TP53 signaling (e.g. caused by TP53 mutations) in both colon and breast cancers, these findings suggest that in addition to its utility for developing multivariate classifiers, density-constrained biclustering (DCB) may also have additional functionality for extracting biologically relevant networks of genes.

See Figure 1 and Table 6 in the Supplementary Material for pictures and additional statistics on our colon cancer top markers See also Section 3 and Table 1 in the Supplementary Material for a comparative enrichment analysis of all subnetwork marker approaches which reveals that ∼75% of our colon cancer top markers are enriched with GO terms which substantially differs from other subnetwork approaches (at most 38% of the top markers are enriched).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Recent studies have strongly confirmed that cancer comes in a great variety of phenotypes as well as multiple evolutionary stages. Here we have explicitly addressed this when searching for systemic subnetwork markers: we employ a biclustering approach—our markers may apply for several but not all cancer samples under examination. As a result, we have outperformed the state-of-the-art approaches, achieving relative increases in prediction accuracy of ∼50% in the most demanding cross-platform instances. Our top-ranked markers contained, for example, well-known dysregulated genes involved in TP53 signaling. In summary, we have demonstrated how to combine the usual benefits of systemic cancer marker approaches with insights on the phenotypical complexity of cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Salim Chowdhury and Mehmet Koyutürk for helpful and forthcoming comments.

Funding: Private donation from David DesJardins, Google Inc (to A.S.C.). M.E. is supported in part by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. P.D. is supported in part by a grant from the MITACS Accelerate Graduate Research Internship Program.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1The signature genes reported in Miller et al. (2005) are 32 such probes chosen such as to achieve maximum training accuracy in the cross-validation scheme.

REFERENCES

- Alizadeh A, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large b-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for high-throughput functional genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D885–D890. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer D, et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 2002;8:816–824. doi: 10.1038/nm733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger M. Mcm2 and mcm5 as prognostic markers in colon cancer: a worthwhile approach. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008;54:197–198. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P, et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Koyutürk M. Identification of coordinately dysregulated subnetworks in complex phenotypes. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2010;15:133–144. doi: 10.1142/9789814295291_0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H-Y, et al. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:140. doi: 10.1038/msb4100180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak R. Towards finding the complete modulome: density constrained biclustering. Burnaby, BC, Canada: Master's thesis, School of Computing Science, Simon Fraser University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Colak R, et al. Dense graphlet statistics of protein interaction and random networks. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2009;14:178–189. doi: 10.1142/9789812836939_0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak R, et al. Module discovery by exhaustive search for densely connected, co-expressed regions in biomolecular interaction networks. PLoS One in press. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich M, et al. Identifying functional modules in protein-protein interaction networks: an integrated exact approach. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i223–i231. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor L, et al. Outcome signature genes in breast cancer: is there a unique set? Bioinformatics. 2005;21:171–178. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor L, et al. Thousands of samples are needed to generate a robust gene list for predicting outcome in cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5923–5928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601231103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon E, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasco M, et al. The p53 pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:70–76. doi: 10.1186/bcr426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgii E, et al. Enumeration of condition-dependent dense modules in protein interaction networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:933–940. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub T, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton O, et al. A sequence-level map of chromosomal break points in the mcf-7 breast cancer cell line yields insights into the evolution of a cancer genome. Genome Res. 2009;19:167–177. doi: 10.1101/gr.080259.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideker T, et al. Discovering regulatory and signaling circuits in molecular interaction networks. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:233–240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L, et al. String 8--a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, et al. Dact3 is an epigenetic regulator of wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer and is a therapeutic target of histone modifications. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ki D, et al. Whole genome analysis for liver metastasis gene signatures in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121:2005–2012. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald F, et al. Molecular Biology of Cancer. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2004. Colorectal cancer. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13550–13555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser F, et al. SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM). Sparks, Nevada, USA: 2009. Mining cohesive patterns from graphs with feature vectors. [Google Scholar]

- Nibbe R, et al. An integrative -omics approach to identify functional sub-networks in human colorectal cancer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald A, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:1937–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabates-Bellver J, et al. Transcriptome profile of human colorectal adenomas. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:1263–1275. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf B, Smola A. Learning with Kernels. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan R, et al. Network-based prediction of protein function. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:88. doi: 10.1038/msb4100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I, et al. Research in Computational Biology (RECOMB) Singapore: Springer; 2008. Detecting disease-specific dysregulated pathways via analysis of clinical expression profiles; pp. 347–359. Vol. 4955 of LNBI. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver M, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, et al. An integrative approach to characterize disease-specific pathways and their coordination: a case study in cancer. BMC Genomics. 2007;9(Suppl. 1):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-S1-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]