Abstract

Motivation: Cancer is a complex disease, triggered by mutations in multiple genes and pathways. There is a growing interest in the application of systems biology approaches to analyze various types of cancer-related data to understand the overwhelming complexity of changes induced by the disease.

Results: We reconstructed a regulatory module network using gene expression, microRNA expression and a clinical parameter, all measured in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from patients having aggressive or non-aggressive forms of prostate cancer. Our analysis identified several modules enriched in cell cycle-related genes as well as novel functional categories that might be linked to prostate cancer. Almost one-third of the regulators predicted to control the expression levels of the modules are microRNAs. Several of them have already been characterized as causal in various diseases, including cancer. We also predicted novel microRNAs that have never been associated to this type of tumor. Furthermore, the condition-dependent expression of several modules could be linked to the value of a clinical parameter characterizing the aggressiveness of the prostate cancer. Taken together, our results help to shed light on the consequences of aggressive and non-aggressive forms of prostate cancer.

Availability: The complete regulatory network is available as an interactive supplementary web site at the following URL: http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/pronet/

Contact: yves.vandepeer@psb.vib-ugent.be

1 INTRODUCTION

During the past century, the basic strategy to decypher biological functions was essentially to concentrate efforts on a very limited set of molecules of interest. This reductive or gene-centric approach has had, and still has, an enormous success, producing immediately applicable results in all areas of molecular biology knowledge. However, it has become clear that biological function can rarely be assigned to an individual molecule but is rather the result of the interactions among a discrete set of various types of molecules (proteins, RNA, metabolites, etc.). Those functional modules are a critical level of biological organization that cannot be identified by the study of their individual components (Hartwell et al., 1999). One of the main goals of systems biology is to determine those modules and their components, by data-mining and integrating high-throughput ‘omics’ data.

Cancer is essentially a genetic disease, characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation and survival of damaged cells, resulting in tumor formation. Unlike other diseases, such as cystic fibrosis or muscular dystrophy, there is no single gene defect that directly ‘causes’ cancer. Cells have multiple safeguards to prevent the effects of mutations appearing in various cancer genes, and it is only when several of those genes are affected that an invasive and potentially lethal tumor develops (Vogelstein and Kinzler, 2004). The picture is further complicated by the fact that new classes of molecules like microRNAs (miRNAs) have been shown to play a crucial role in tumorigenesis, and therefore should be taken into account (Esquela-Kerscher and Slack, 2006). Prostate cancer is the third most common cancer in men worldwide and occurs principally in the United States, Canada and northwestern Europe, but is uncommon in Asian countries and South America (Quinn and Babb, 2002). Prostate cancer is a complex disease, and finding the genetic causes of this disease has proven to be difficult, even if genome-wide association studies have recently detected a number of genetic variants, gene fusions and expression signatures associated with this disease (Witte, 2008). Furthermore, the progression of prostate cancer is also complex, with ‘only’ 10% of the patients being diagnosed with an aggressive form that can evolve to threaten their life. The determinants of this outcome are largely unknown (Lu-Yao et al., 2002).

There is an increasing interest in systems biology approaches for the discovery of genes associated with cancer (Hood et al., 2004; Hornberg et al., 2006). Those approaches help to simplify the overwhelmingly complex picture that is often coming out of more traditional approaches by constructing more easily interpretable network representations of the underlying system and deriving concrete, experimentally verifiable hypotheses. The integration of clinical data in a robust framework that would allow the identification of modules that are pathologically altered in disease has been identified as one of the major challenges for network biology (Barabási and Oltvai, 2004).

Here, we used the LeMoNe algorithm to reconstruct a regulatory module network linked to prostate cancer using a large dataset of lymphoblastoid cells samples for which expression levels were measured for genes as well as miRNAs. LeMoNe uses ensemble-based probabilistic optimization techniques to identify clusters of co-expressed genes and their putative regulators (Joshi et al., 2008, 2009; Michoel et al., 2007). The algorithm has been validated and applied on various biological data sets (Michoel et al., 2009; Vermeirssen et al., 2009). Recently, we applied it to a set of cancer samples of various origins, for which expression data were available for both genes and a limited set of miRNAs. A couple of miRNAs were identified as high-scoring regulators for several modules of co-expressed genes, and a miRNA was validated experimentally as a regulator of a module linked to epithelial homeostasis, with a possible role in epithelial to mesenchymal transition (Bonnet et al., 2010). So far, we used expression data measurements to assign regulators to clusters of co-expressed genes, but in this study we further extended the algorithm to simultaneously evaluate a heterogeneous set of candidate regulators which can be continuous-valued or discrete. In addition to combining transcription factors and miRNAs as regulators, we have also associated a clinical parameter to the condition-dependent expression levels of a module, gaining further insight in the regulatory processes.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data sets

We used datasets generated for a previous study (Wang et al., 2009b), where blood samples were taken from 90 male patients having a median age of 68 years. The lymphocytes were then transformed with Epstein–Barr virus to create lymphoblastoid cell lines. Total RNA was extracted and profiled for mRNA transcripts and miRNAs for the 90 samples using the Illumina human-6 V2 BeadChip and Illumina microRNA expression profiling panel, respectively. We downloaded normalized expression data sets and sample information from the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (GSE14794) using the package GEOquery (Davis and Meltzer, 2007) from the R statistical package (R Development Core Team, 2009).

2.2 LeMoNe module network algorithm

We designed and tested the LeMoNe (Learning Module Networks) algorithm in previous studies (Joshi et al., 2008, 2009; Michoel et al., 2007). The algorithm extends the method of Segal et al. (2003) to infer regulatory modules and their specific regulators from gene expression data by using a more representative solution extracted from an ensemble of possible statistical models to explain the data. LeMoNe infers a module network in two major stages. The first one is a two-way clustering of genes and conditions, using a Gibbs sampling procedure (Joshi et al., 2008). In order to avoid local optima, multiple clustering solutions are generated and subsequently integrated in a final set of so-called tight clusters, corresponding to sets of genes that are frequently associated across all the clustering solutions. In the second stage, the algorithm infers a prioritized list of regulators for each cluster of co-expressed genes. More precisely, a hierarchical tree is build by grouping sets of conditions (corresponding in this case to samples taken from different patients) having similar means and standard deviation. Regulators are assigned to each node of the tree by logistic regression on the regulator expression values to predict the assignment of conditions to each side of the tree node (Joshi et al., 2009). Regulators having a distinct expression pattern on each side of a given tree node will get a high probabilistic score. Multiple statistically equivalent partitions of conditions are generated for each cluster of co-expressed genes and an ensemble approach is used to sum the strength with which a regulator participates in each regulatory tree. A global score is calculated which reflects the overall statistical confidence, and which is used for prioritizing the whole list of regulators for a given set of co-expressed genes. The mathematical details of the algorithm can be found in Joshi et al. (2009). The LeMoNe software package can be downloaded from our website, is open-source and free of charge for academic use (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/software/details/lemone).

2.3 Integrating discrete and heterogeneous continuous-valued regulators

As explained above, regulators are assigned to a co-expression cluster by using logistic regression on the binary splits of a set of hierarchically linked condition clusters. More precisely, let 𝒞0 and 𝒞1 be two disjoint sets of conditions. Given a regulator with expression value x in some condition, our model assumes there is a (hidden) binomially distributed random variable Y such that Y = 0 if the condition is assigned to 𝒞0 and Y = 1 if it is assigned to 𝒞1, with probability

For a continuous-valued regulator, the training data for a regulator R consists of a set of expression values xm across all measured conditions m. Furthermore, given the partition of conditions and their hierarchical tree, we know at each tree node which conditions m belong to 𝒞0 and which to 𝒞1. Hence, using Bayes' rule, we can determine the parameters β and z which maximize the posterior probability of assigning regulator R. This posterior probability is then used as the score for R at this particular tree node and combined with the scores at other nodes to compute a global assignment score. The parameter z is interpreted as a split value, meaning if R is highly expressed (xm > z) the condition is assigned to one side of the split and if R is lowly expressed (xm < z) to the other side. The parameter β is determined by how well a regulator fits the separation of conditions: if xm > z for all m ∈ 𝒞1 and xm < z for all m ∈ 𝒞0 (or vice versa), we can take β = +∞ and obtain a maximal posterior probability. If there is no split value which achieves a good separation of conditions, β will be close to 0 leading to low values of the posterior probability. See Joshi et al. (2009) for more details.

Clearly, there is no need for the values x to be comparable in absolute terms to the expression values determining the co-expression clusters. This is exploited to assign miRNA regulators. Furthermore, there is also no need for the values x to be continuous. In this article, we considered discrete regulators which can take two values, say 0 and 1. Then the parameter z becomes redundant and we set it to z = 0.5, while β is determined as before by maximizing the posterior probability. As we are using a probabilistic model and the final regulator score is defined by a posterior probability, the scores of mRNA, miRNA and discrete regulators can all be integrated and compared on the same scale to determine the final module network with heterogeneous regulators.

2.4 Supplementary data web site

In order to facilitate the analysis and the browsing of the results of this study, we have set up a dedicated supplementary web site (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/pronet/). The user can search for a gene of interest by his Illumina gene code, common gene name (HUGO symbol) and gene description. Each search will return a list of modules where the search term was found. The user can then click on the module name to have a detailed list of the module genes and regulators. Users also have the possibility to leave one (or more) comments on each module of interest.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Inference of a module network linked to prostate cancer

In this study, we used the LeMoNe algorithm (see Section 2) to build a regulatory module network from gene expression profiles generated from immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines produced from blood cell samples of 90 patients having aggressive or nonaggressive prostate cancer (Wang et al., 2009a, b). The output of the algorithm is a set of clusters of co-expressed genes, with a prioritized list of high-scoring regulators attached to each cluster. A cluster of co-expressed genes plus its list of regulators constitute a module, and the ensemble of modules and their relationships compose the module network.

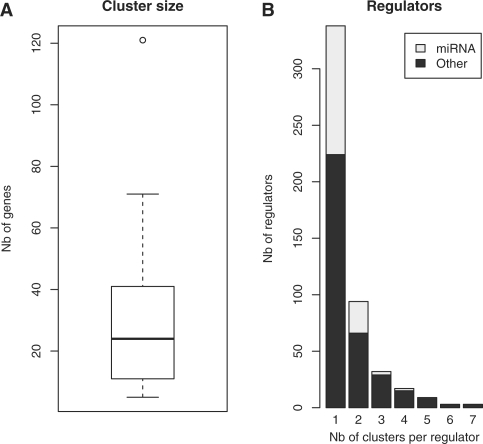

For the first stage of the algorithm, we selected genes showing a differential expression (SD < 0.2) across the set of samples, resulting in a set of 2192 genes that was used as input for the clustering procedure. We generated 50 different clustering solutions that were integrated to identify tight clusters of genes that are consistently clustered together. The result was a set of 43 tight clusters having more than five genes, that do not overlap and represent a total of 1259 genes. The clusters have a variable number of genes, with a median size of 24 genes. Twenty-five percent of the clusters have less than 11 genes and 75% have less than 41 genes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Boxplot representation of the size of the 43 tight clusters inferred by LeMoNe (A). Number (Nb) of clusters per regulator for high scoring regulators (B). The proportion of miRNAs is indicated in light grey.

The set of 43 tight clusters was used as input for the second stage of the algorithm, the assignment of regulators. The probabilistic score calculated for each regulator reflects how well its expression profile predicts the condition-dependent expression level of the genes in a cluster. Furthermore, we can use this score on heterogeneous types of regulators, including ones having discrete values (see Section 2). For this study, we have used three different types of regulators. First, we selected all transcription factors and signal transducers from the gene expression dataset, using the GO categories ‘transcription factor activity’ (GO:0003700) and ‘signal transducer activity’ (GO:0004871). This selection resulted in a set of 1558 genes. Second, we added a set of 735 microRNA expression profiles that were measured on the same samples, but using a distinct microarray platform (Wang et al., 2009a, b). Third, we also used as a ‘regulator’ a clinical parameter, the Gleason grade, a discrete score assigned by a pathologist based on the microscopic appearance of prostate tissue biopsies. High values of Gleason grade are linked to more aggressive forms of prostate cancer characterized by a worse prognosis for the patient. The 90 samples in the dataset have been classified as ‘high’ or ‘low’ Gleason score.

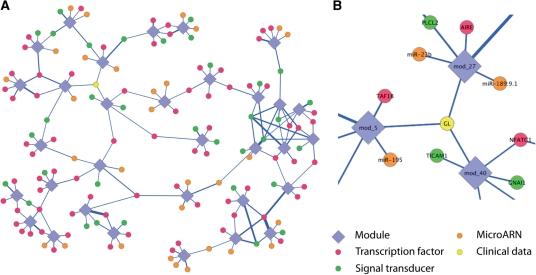

A total of 77 374 regulator–module assignments were made by the algorithm, from which we selected the top 1% as high-scoring candidate regulators (774 regulator–module pairs). For each regulator assigned to a module, the algorithm is also selecting another one at random, thus defining a distribution of randomly assigned regulators. In this study, the distribution of all random regulators has a median score of 9.37, with a maximal score of 60.11. On the other hand, the top regulators (i.e. the top 1% of all assigned regulators) have a median score of 228, with a minimum value of 107.47. Therefore the minimum score for a top regulator is still 3.8 times higher than the maximal score for a randomly assigned regulator, thereby demonstrating that the top regulators score is far greater from what could be expected by chance. There are 496 unique regulators in the top 1% selection. Most of the regulators are assigned to one cluster (68%), but some are assigned to two or more (Figs 1 and 2). Within this set, a total of 148 miRNAs have been selected (30% of all high-scoring regulators). Some miRNAs are also assigned to more than one cluster (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Simplified representation of the module network inferred by the LeMoNe algorithm. Clusters of co-expressed genes have diamond shapes, while regulators are symbolized by circles. The color of the circle correspond to a given type of regulator. The thickness of the edges is proportional to the score of a regulator for a given module. For clarity, some clusters are not represented and we have limited the regulators to six per module. (B) Zoom on the module network representation. The yellow regulator labeled GL represent a clinical parameter, the Gleason score, which is connected to three different clusters.

3.2 Modules are enriched with specific gene ontology categories

We calculated enrichment of GO (Gene Ontology) categories for the 43 tight clusters using the BiNGO tool (Maere et al., 2005). A total of 29 tight clusters have at least one GO category overrepresented at the 0.05 significance level (corrected P-values). There are 580 different GO categories overrepresented. A selection of GO categories overrepresented for various modules is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected GO categories for various modules of the prostate cancer network inferred in this study

| Module ID | Ng | GO category | Corrected P-value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 59 | GO:0043170 | 1.45E-02 | Macromolecule metabolic process |

| GO:0006374 | 1.45E-02 | Nuclear mRNA splicing | ||

| GO:0006395 | 1.45E-02 | RNA splicing | ||

| GO:0006397 | 1.45E-02 | mRNA processing | ||

| GO:0008152 | 3.21E-02 | Metabolic process | ||

| GO:0022402 | 3.62E-02 | Cell cycle process | ||

| 2 | 54 | GO:0048002 | 3.68E-03 | Antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen |

| GO:0006955 | 1.55E-02 | Immune response | ||

| GO:0002376 | 1.56E-02 | Immune system process | ||

| GO:0008283 | 4.05E-02 | Cell proliferation | ||

| 4 | 46 | GO:0007067 | 8.42E-24 | Mitosis |

| GO:0007049 | 2.42E-20 | Cell cycle | ||

| GO:0022402 | 2.51E-17 | Cell cycle process | ||

| GO:0000074 | 9.25E-09 | Regulation of cell cycle | ||

| GO:0000075 | 2.30E-07 | Cell cycle checkpoint | ||

| GO:0008283 | 1.77E-04 | Cell proliferation | ||

| 7 | 29 | GO:0009615 | 4.72E-05 | Response to virus |

| GO:0051707 | 7.30E-04 | Response to other organism | ||

| GO:0006955 | 8.23E-04 | Immune response | ||

| GO:0009607 | 1.92E-03 | Response to biotic stimulus | ||

| GO:0002376 | 3.31E-03 | Immune system process | ||

| 8 | 46 | GO:0007243 | 4.55E-04 | Protein kinase cascade |

| GO:0006950 | 6.85E-04 | Response to stress | ||

| GO:0006915 | 2.60E-03 | Apoptosis | ||

| GO:0012501 | 2.60E-03 | Programmed cell death | ||

| GO:0007242 | 1.16E-02 | Intracellular signaling cascade | ||

| 11 | 42 | GO:0000245 | 3.67E-03 | Spliceosome assembly |

| GO:0000074 | 2.37E-02 | Regulation of cell cycle | ||

| GO:0048523 | 2.37E-02 | Negative regulation of cellular process | ||

| GO:0006374 | 2.37E-02 | Nuclear mRNA splicing | ||

| 12 | 31 | GO:0007154 | 2.85E-03 | Cell communication |

| GO:0007165 | 3.60E-03 | Signal transduction | ||

| GO:0045767 | 9.42E-03 | Regulation of anti-apoptosis | ||

| GO:0007242 | 3.73E-02 | Intracellular signaling cascade | ||

| 14 | 16 | GO:0006066 | 1.06E-02 | Alcohol metabolic process |

| GO:0019318 | 1.37E-02 | Hexose metabolic process | ||

| GO:0005996 | 1.37E-02 | Monosaccharide metabolic process | ||

| GO:0005975 | 2.19E-02 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | ||

| GO:0002252 | 3.62E-02 | Immune effector process | ||

| 18 | 13 | GO:0006334 | 4.74E-19 | Nucleosome assembly |

| GO:0031497 | 7.18E-19 | Chromatin assembly | ||

| GO:0006323 | 6.53E-18 | DNA packaging | ||

| GO:0006333 | 7.42E-18 | Chromatin assembly or disassembly | ||

| GO:0006952 | 6.54E-03 | Defense response | ||

| 21 | 9 | GO:0019882 | 1.30E-14 | Antigen processing and presentation |

| GO:0006955 | 3.38E-10 | Immune response | ||

| 22 | 23 | GO:0006416 | 7.53E-09 | Translation |

| GO:0010467 | 6.55E-05 | Gene expression | ||

| 29 | 32 | GO:0008652 | 3.08E-04 | Amino acid biosynthetic process |

| GO:0019752 | 6.73E-04 | Carboxylic acid metabolic process | ||

| 38 | 11 | GO:0007010 | 1.22E-02 | Cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis |

| GO:0046907 | 1.80E-02 | Intracellular transport | ||

| GO:0007067 | 1.98E-02 | Mitosis | ||

| 41 | 6 | GO:0000075 | 1.63E-02 | Cell cycle checkpoint |

| GO:0007050 | 1.63E-02 | Cell cycle arrest | ||

| GO:0051242 | 3.55E-02 | Positive regulation of cellular process | ||

| GO:0000074 | 3.55E-02 | Regulation of cell cycle | ||

| GO:0042127 | 3.95E-02 | Regulation of cell proliferation | ||

Ng, number of genes in the module.

Several modules are enriched for cell cycle-related categories (for example modules 0, 2, 4, 11, 41). This result is highly consistent with previous analyses that also found cell-cycle enrichment in gene clusters inferred on the same dataset but using different statistical approaches (Wang et al., 2009a, b). As an example, module 4 is highly enriched in cell cycle-related genes (corrected P-value 2.4E-20, Table 1). It has a list of 13 high-scoring regulators, including five miRNAs. Several of those are known regulators of the cell cycle. The top regulator, HMGB2, is a DNA-bending/looping protein that is known to bind p53, the well-known tumor suppressor gene inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Stros et al., 2004). The second regulator in the list is one of the core regulators of the cell cycle, E2F2 (Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). The third regulator is UHRF1, a member of a subfamily of RING-finger type E3 ubiquitin ligases that binds to specific DNA sequences and recruits a histone deacetylase to regulate gene expression. UHRF1 is playing a crucial role at the G1/S transition of the cell cycle (Jeanblanc et al., 2005). The fourth regulator is also a well-characterized regulator of the cell cycle. FOXM1, a member of the FOX family of transcription factors, regulates a large set of G2/M specific genes (Laoukili et al., 2005). FOXM1 was characterized as a proto-oncogene, and was found to be upregulated in many types of cancer, including prostate tumors (Kalin et al., 2006). Amongst the miRNAs selected as regulators of module 4 is miR-320d, which affects the cell cycle G1/S transition through CDK6 under specific conditions (Duan et al., 2009).

Several modules are statistically enriched for other functional categories like nucleosome and chromatin assembly (module 18, P-value 4.74E-19 and 7.18E-19, respectively), translation (module 22, P-value 7.53E-09), immune response (module 2, P-value 1.55E-02, module 7, P-value 8.23E-04), response to stress (module 8, P-value 6.85E-04), cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis (module 38, P-value 1.22E-02), cell communication and signal transduction (module 12, P-values 2.85E-03 and 3.60E-03, respectively), response to stress (module 8, P-value 6.85E-04) and alcohol metabolic process (module 14, P-value 1.06E-02). Previous studies on the same dataset have also identified cell communication and signal transduction (Wang et al., 2009b), but our approach enriches the results with several new functional categories. For example, module 18 is enriched for nucleosome and chromatin assembly, which could be linked to the cell cycle, but might also point to chromatin modifications linked to epigenetic changes. Module 2 and 7 are linked to immune response, which has been characterized as playing a role in tumor initiation and promotion (Pollard, 2004).

Wang et al. (2009a) performed a computational analysis on the same dataset. By using a weighted gene co-expression network analysis, they identified a set of four modules, with one of them being highly enriched in various cell cycle-related GO categories. Our approach, based on a different algorithm, has also clearly identified cell cycle-related modules as well as novel GO categories, like immune response, and therefore is enriching the results obtained previously. This become particularly evident when comparing the top GO categories identified in the study of (Wang et al., 2009a) (Table 2), where most categories identified in their study are clearly related to the cell cycle, while in this analysis we have not only many cell cycle-related categories, but also novel categories like the immune response. Further analysis of those novel modules could help to identify key genes or markers related to prostate cancer.

Table 2.

Top GO categories enriched in the analysis of Wang et al. (2009a) and this study

| Wang et al. (2009a) |

This study |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| GO category | P | GO category | P |

| Cell cycle | 3.4E-26 | Mitosis | 8.4E-24 |

| DNA replication | 1.6E-13 | Cell cycle | 2.4E-20 |

| Chromosome | 2.1E-13 | Chromatin assembly or | |

| Disassembly | 7.4E-18 | ||

| Interphase | 2.4E-06 | Immune response | 3.4E-10 |

| Regulation of mitosis | 7.7E-07 | Translation | 7.5E-09 |

| DNA metabolic process | 1.9E-07 | DNA metabolic process | 2.8E-07 |

| Chromosome segregation | 2.2E-07 | Chromosome segregation | 3.3E-07 |

| Microtubule-based process | 1.1E-05 | Cellular biosynthetic process | 2.7E-05 |

| DNA replication factor C | Response to stimulus | 3.5E-05 | |

| Complex | 3E-03 | ||

| Condensed chromosome | 7.2E-03 | Organic acid metabolic | |

| process | 6.7E-04 | ||

3.3 MiRNAs are selected as high-scoring regulators

Almost 30% of the high-scoring regulators are miRNAs. Even if we restrict the selection to the three best regulators for each module, there are still 17 miRNAs, including six that are selected as best regulators (having the highest score) for a module (miR-451 for module 7, miR-125a-5p for module 18, miR-221 for module 24, miR-767-3p for module 32, miR-132 for module 33 and miR-181a* for module 35). From this restricted list of 17 miRNAs, three were also identified in the study by Wang et al. (2009a) (miR-221, miR-222 and miR-551) as having a significant association with prostate cancer.

From the 148 unique miRNAs selected as high-scoring regulators in this study, 64 have already been implicated in various diseases, mostly cancer (Jiang et al., 2009). For example, miR-451 has been implicated as causal in colorectal cancer (Bandres et al., 2009), breast cancer (Kovalchuk et al., 2008), glioblastoma (Gal et al., 2008) and gastric cancer (Bandres et al., 2009). MiR-221 has been identified in the previous analysis of this dataset (Wang et al., 2009a) and is also selected as a high-scoring regulator in our study. This miRNA has been identified as a causal factor in numerous forms of cancer (Jiang et al., 2009), including prostate cancer (Galardi et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2009; Tong et al., 2008). MiR-132, selected as the best regulator for module 33, has been linked to various diseases, including colorectal cancer (Xi et al., 2006), pituitary adenoma (Bottoni et al., 2007) and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Calin et al., 2004). In conclusion, our analysis confirms miRNAs that have been previously identified from the same dataset (e.g. miR-221), finds miRNAs that have been characterized as causal in various forms of cancer (e.g. miR-451), and predicts novel miRNAs that have not been previously reported to be involved in a disease (e.g. miR-767-3p).

3.4 Assignment of a clinical parameter as a regulator

Only a minority of the patients (∼10%) that do show histologic evidence of prostate cancer will develop a clinically significant form, potentially severe. Distinguishing the factors that are relevant and crucial for the characterization of the degree of aggressiveness of the disease is thus a key question that novel approaches, like systems biology, might help to tackle. More specifically, it might be useful to integrate various types of data, like clinical parameters, to try to shed some light on this problem. The Gleason grade system has proven to be a reliable indicator of the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. We have included this clinical parameter as a binary variable (either low or high for all samples) as a ‘regulator’, along with transcriptions factors, signal transducers and miRNAs.

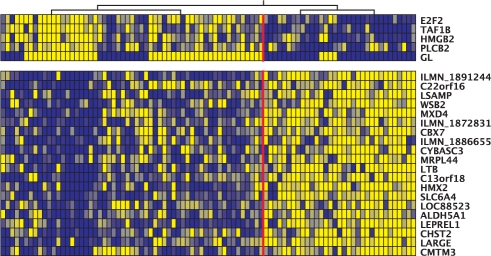

This parameter has been selected as a high-scoring regulator for four different modules (Fig. 2B and Supplementary web site). For example, it is assigned as the fifth best regulator for module 5 (Fig. 3). The figure shows that the Gleason score values are inversely correlated with the expression levels of the module, defined by the first node of the hierarchical tree (red line on the figure), just like the four other regulators. Although this module does not have any statistically enriched functional category, there are several genes annotated for cell proliferation, cell growth and mitosis. Furthermore, amongst the top regulators are the well-known regulators of cell cycle and cell proliferation E2F2 and HMGB2 (Stros et al., 2004; Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). The Gleason score is also linked to module 38, which is enriched in genes involved in mitosis (Table 1). Of course, this parameter is not a regulator per se, and the result should not be interpreted as having a causal regulatory role. Instead, we can postulate that the degree of aggressiveness of the disease might trigger subtle changes in expression in the biological functions represented by these modules.

Fig. 3.

Module 5. The upper panel represent the high-scoring regulators, ordered by decreasing score. The GL is the fifth regulator in the list. The lower panel represent the module genes. Each column represent a different sample. For clarity, only the five best regulators and a selection of the module genes are represented. The expression of the genes and regulators is color coded, with the dark blue representing low expression, while bright yellow indicates highly expressed genes. The hierarchical tree on top of the figure is one of the trees used to assign the regulators. The vertical red line represent the partition of samples defined by the first node of the tree.

For the current dataset, only one clinical parameter was publicly available, but usually many more are measured. This type of data integration might therefore be extremely valuable for a better comprehension of the clinical aspects of various cancers by linking molecular data such as gene and miRNA expression to specific disease phenotypes.

4 CONCLUSION

In this study, we have applied a module network algorithm to a large expression data set measured on lymphoblastoid cell lines coming from patients having different forms of prostate cancer. Compared to our previous applications of the algorithm, we have further extended it to simultaneously evaluate a heterogeneous set of candidate regulators which can be continuous-valued or discrete.

We predicted a module network of 43 modules of co-expressed genes with their associated high-scoring regulators. Most of the modules show enrichment for specific GO categories. Several of those categories are related to cell cycle and mitosis activities, which is consistent with previous studies on the same dataset. Almost 30% of the predicted regulators are miRNAs, and many of them have been characterized as causal in many diseases, including cancer. Our results also suggest novel miRNA candidates that could be linked to prostate cancer. This study also associate the Gleason score, a clinical parameter to modules enriched in cell growth and mitosis.

Our study clearly demonstrate the interest of systems biology approaches to study cancer and its consequences, more particularly by the integration of heterogeneous sets of candidate regulators. This type of analysis can be applied to various cancer types and tissues for which relevant expression data for mRNA, miRNA and various clinical parameters are available.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Kenny Billiau for the Supplementary Material web site setup.

Funding: Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie (IWT) grant for the Strategisch BasisOnderzoek (SBO) project Bioframe; Interuniversity Attraction Pole grant (IUAP) for the BioMaGNet project (Bioinformatics and Modelling: from Genomes to Networks, ref. p6/25).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bandres E, et al. microRNA-451 regulates macrophage migration inhibitory factor production and proliferation of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:2281. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási A, Oltvai Z. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet E, et al. Module network inference from a cancer gene expression data set identifies microRNA regulated modules. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoni A, et al. Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs by microarray: a possible role for microRNA genes in pituitary adenomas. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;210:370. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin G, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2004;101:11755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Meltzer P. Geoquery: a bridge between the gene expression omnibus (geo) and bioconductor. Bioinformatics. 2007;14:1846–1847. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, et al. MiR-320 and miR-494 affect cell cycles of primary murine bronchial epithelial cells exposed to benzo [a] pyrene. Toxicology in Vitro. 2009;24:928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack F. Oncomirs: microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal H, et al. MIR-451 and Imatinib mesylate inhibit tumor growth of Glioblastoma stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;376:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galardi S, et al. miR-221 and miR-222 expression affects the proliferation potential of human prostate carcinoma cell lines by targeting p27Kip1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L, et al. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature. 1999;402:47. doi: 10.1038/35011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood L, et al. Systems biology and new technologies enable predictive and preventative medicine. Sci. Signal. 2004;306:640. doi: 10.1126/science.1104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberg J, et al. Cancer: a systems biology disease. Biosystems. 2006;83:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanblanc M, et al. The retinoblastoma gene and its product are targeted by ICBP90: a key mechanism in the G1/S transition during the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2005;24:7337–7345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, et al. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, et al. Analysis of a Gibbs sampler method for model-based clustering of gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:176. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, et al. Module networks revisited: computational assessment and prioritization of model predictions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:490. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin T, et al. Increased levels of the FoxM1 transcription factor accelerate development and progression of prostate carcinomas in both TRAMP and LADY transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1712. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk O, et al. Involvement of microRNA-451 in resistance of the MCF-7 breast cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2152. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laoukili J, et al. FoxM1 is required for execution of the mitotic programme and chromosome stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:126–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu-Yao G, et al. Natural experiment examining impact of aggressive screening and treatment on prostate cancer mortality in two fixed cohorts from Seattle area and Connecticut. Br. Med. J. 2002;325:740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S, et al. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michoel T, et al. Validating module network learning algorithms using simulated data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8(Suppl. 2):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-S2-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michoel T, et al. Comparative analysis of module-based versus direct methods for reverse-engineering transcriptional regulatory networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 2009;3:49. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard J. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M, Babb P. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part I: international comparisons. BJU Int. 2002;90:162–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.2822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, et al. Module networks: identifying regulatory modules and their condition-specific regulators from gene expression data. Nat. genet. 2003;34:166–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stros M, et al. High-affinity binding of tumor-suppressor protein p53 and HMGB1 to hemicatenated DNA loops. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7215–7225. doi: 10.1021/bi049928k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, et al. The role of microRNA-221 and microRNA-222 in androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, et al. MicroRNA profile analysis of human prostate cancers. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;16:206–216. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi J, Lees J. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeirssen V, et al. Transcription regulatory networks in Caenorhabditis elegans inferred through reverse-engineering of gene expression profiles constitute biological hypotheses for metazoan development. Mol. BioSyst. 2009;5:1817–1830. doi: 10.1039/B908108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler K. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, et al. Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009a;69:9490. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals microRNA-correlated genes and biological processes in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. PLoS One. 2009b;4:e5878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte J. Prostate cancer genomics: towards a new understanding. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;10:77–82. doi: 10.1038/nrg2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y, et al. Differentially regulated micro-RNAs and actively translated messenger RNA transcripts by tumor suppressor p53 in colon cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:2014. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]