Abstract

Motivation: The identification of genes involved in specific phenotypes, such as human hereditary diseases, often requires the time-consuming and expensive examination of a large number of positional candidates selected by genome-wide techniques such as linkage analysis and association studies. Even considering the positive impact of next-generation sequencing technologies, the prioritization of these positional candidates may be an important step for disease-gene identification.

Results: Here, we report a large-scale analysis of spatial, i.e. 3D, gene-expression data from an entire organ (the mouse brain) for the purpose of evaluating and ranking positional candidate genes, showing that the spatial gene-expression patterns can be successfully exploited for the prediction of gene–phenotype associations not only for mouse phenotypes, but also for human central nervous system-related Mendelian disorders. We apply our method to the case of X-linked mental retardation, compare the predictions to the results obtained from a previous large-scale resequencing study of chromosome X and discuss some promising novel candidates.

Contact: rosario.piro@unito.it

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Individuals belonging to the same species show not only phenotypic variations that influence all biological aspects of the organism in more or less profound ways, including physiology, metabolic pathways and development, but also susceptibility to diseases.

In the last years, genome-wide techniques such as linkage analysis and association studies have been very successful in establishing the molecular basis of many phenotypic traits. However, these approaches often select loci containing many hundreds of positional candidates, the experimental evaluation of which can be time-consuming and expensive. Therefore, computational approaches to disease-gene prediction or prioritization can be an important step prior to further empirical analysis in a laboratory. In silico disease-gene prediction can be based on different types of information, such as sequence properties (López-Bigas and Ouzounis, 2004), functional annotation (Freudenberg and Propping, 2002; Turner et al., 2003), text-mining of biomedical literature (Perez-Iratxeta et al., 2002; Tiffin et al., 2005), protein–protein interactions (Lage et al., 2007; Oti et al., 2006), high-throughput gene-expression data (Ala et al., 2008; Miozzi et al., 2008; Mootha et al., 2003) or combinations of these (Aerts et al., 2006; Rossi et al., 2006). While some of these approaches are clearly biased towards already consolidated knowledge, e.g. the mining of functional annotations and biomedical literature, others allow for a less biased evaluation of candidate genes. Avoiding such a bias, that tends to diminish the value of all candidate genes about which little or nothing is known, is a key problem of disease gene prediction methodologies. For this reason, approaches that rely on (or at least include) genome-wide high-throughput data, like the one proposed in this article, are generally preferable.

The introduction of next-generation sequencing technologies is likely to have a significant impact on disease-gene discovery by speeding up the identification of potentially disease-relevant mutations (Mardis, 2007). However, especially if large sets of positional candidates are involved, a high number of sequence variations can be expected to be found. Cargill et al. (1999), for example, found 185 non-synonymous and 207 synonymous polymorphisms in a screen of the coding regions of 106 human genes relevant to cardiovascular disease, endocrinology and neuropsychiatry. During a screen of the coding exons of 718 genes on chromosome X from 208 families for mutations causing X-linked mental retardation (XLMR), Tarpey et al. (2009) found mutations in three novel and several known disease genes, but could not, for most families, identify the genetic cause of XLMR, despite the identification of a large number of missense and even truncating mutations. These results illustrate that even with the aid of novel technologies candidate evaluation remains a difficult task, thus providing a rationale for the inclusion of computational predictions or prioritizations in the evaluation process.

High-throughput expression data from microarray experiments are valuable as a potentially unbiased source of information for comparing the expression profiles of candidate genes with those of ‘reference genes’ known to be (directly or indirectly) associated to a phenotype. This ‘guilt-by-association’ approach, however, has usually been applied to heterogeneous datasets containing samples from multiple tissues and cell types (Aerts et al., 2006; Ala et al., 2008; Miozzi et al., 2008; Rossi et al., 2006).

Traditional high-throughput expression data, although being highly informative, have the shortcoming of carrying only limited spatial information: although samples are usually associated to specific tissues and organs, often no detailed 3D localization of samples within a tissue or organ is recorded. This may be a problem, especially for tissues or organs characterized by a high degree of spatial organization, such as the central nervous system (CNS). Some of the microarray or EST expression datasets that have so far been used for disease gene prediction—see for example Aerts et al. (2006) and Ala et al. (2008)—contain subsets for the brain or the CNS that have a somewhat more detailed anatomical (and hence in some sense spatial) annotation, associating the expression data to specific brain or CNS regions, but coverage is mostly sparse, that is, only samples from arbitrary, non-consecutive positions within these regions are available.

Also, due to limitations in sample dissection, most available datasets represent ‘average’ expression levels over several cell types within a complex, heterogeneous tissue. More selective sample preparation, e.g. based on laser capture microdissection (Emmert-Buck et al., 1996), that yields better resolutions, is still uncommon.

In the last few years, different high-throughput methods have been implemented on a genome-wide scale to provide detailed spatial maps of gene expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels. For instance, high resolution (1 mm3) voxelation, followed by microarray or mass spectrometry analysis, has led to the production of an expression map of a single coronal slice of the mouse brain for approximately 20 000 genes and 1028 proteins (Chin et al., 2007). Moreover, multi-dimensional fluorescence microscopy (Schubert et al., 2006) and imaging mass spectrometry (Stoeckli et al., 2001) have recently shown their potential. Finally, although being based on the more traditional in situ hybridization (ISH) technology, the mRNA gene-expression map of the entire adult mouse brain provided by the Allen Brain Atlas (ABA) project (Lein et al., 2007) is a particularly important resource, both for its high resolution and for its great anatomical coverage. The potential usefulness of this resource for disease-gene identification is underscored by a previous pilot study, which established that genes sharing similar 3D expression profiles in the ABA are likely to share similar biological function (Liu et al., 2007).

The aim of this article is to provide a proof-of-concept for the suitability of spatially mapped gene expression for candidate gene prioritization. For this purpose, we first use a leave-one-out procedure to show how the involvement of genes in mouse phenotypes can be predicted. We extend the scope of our work by demonstrating that the co-expression of genes across the mouse atlas is also relevant for the prioritization of candidate genes for human CNS-related Mendelian disorders. Finally, we apply the method to the particularly complex case-study of XLMR, evaluating its performance on genes already known to be involved in the syndrome and using this knowledge to pinpoint some outstanding novel candidates.

2 METHODS

2.1 Spatial mouse brain gene-expression data

We downloaded spatial gene-expression data for 18 389 of around 20 000 genes from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (10 November 2009), using the Application Programming Interface (API) provided by the ABA website. Only sagittal ISH image series with antisense probes for genes with defined Entrez gene IDs were considered. In case of multiple image series per gene, only the most recent was used, since ISH for about 15% of the genes had been repeated with redesigned probes (e.g. due to higher specificity) or other process improvements (Jones et al., 2009). The downloaded expression patterns provide expression levels for the entire brain, smoothed over evenly spaced voxels (cubes) with a side length of 200 μm.

2.2 Mapping to human homologs

For the purpose of prioritizing human disease genes, the expression profiles from the mouse brain were mapped to human Entrez gene IDs using NCBI's HomoloGene build 64 (Sayers et al., 2010). Only unambiguous mappings were considered, yielding a total of 14 916 human Entrez gene IDs with an associated expression pattern from the mouse brain.

2.3 Mouse phenotypes

Information about mouse phenotypes was obtained from the Mouse Genome Database (MGD), release 4.32 (Bult et al., 2008). All 131 phenotypes containing the expressions ‘central nervous system’ and ‘brain’ (this includes ‘brainstem’, ‘forebrain’, etc.) in their denomination or short description and having at least two directly associated genes were considered (such that one can be taken as a candidate and one as a reference gene in the leave-one-out validation); the 77 CNS- or brain-related phenotypes with more than 20 genes were excluded, restricting the search to cases with less available information. This choice reflects the fact that predictions are likely to be particularly important for less well-characterized phenotypes. On average 7.8 genes were associated to each of the 131 phenotypes.

2.4 Human Mendelian disease

Information on human Mendelian disease phenotypes was obtained from OMIM (Amberger et al., 2009; Sayers et al., 2010) on 17 June 2009. Only the 749 phenotype entries of known molecular basis (OMIM symbol: #) containing the term ‘central nervous system’ in their Clinical Synopsis section were considered. The lists of known associated disease genes (mim2gene) were obtained from Entrez Gene (Sayers et al., 2010) on 16 June 2009. Between 1 and 25 genes (on average 1.3 genes) were associated to each OMIM phenotype ID; only six phenotypes (<1%) had 10 or more associated genes. The 659 phenotypes with a single associated gene (88%) were not excluded because reference genes for the leave-one-out validation can be taken from similar phenotypes (see below).

2.5 Similarity of human disorders

To measure the pairwise similarity of OMIM phenotype entries, we processed the textual descriptions of all OMIM phenotype entries (not limited to brain- or CNS-related disorders) using MimMiner, essentially as described by van Driel et al. (2006).

MimMiner scores are normalized and range from 0 (unrelated) to 1 (highly related or identical). Since is was established that similar phenotypes can be identified with reasonable accuracy considering a minimum score of 0.4 (van Driel et al., 2006), we used the same threshold for our work. Therefore, with exception of the XLMR case study (Section 3), we consider as ‘similar phenotypes’ those pairs of OMIM phenotype entries that have a similarity score of at least 0.4 in our updated MimMiner database.

2.6 Candidate gene prioritization

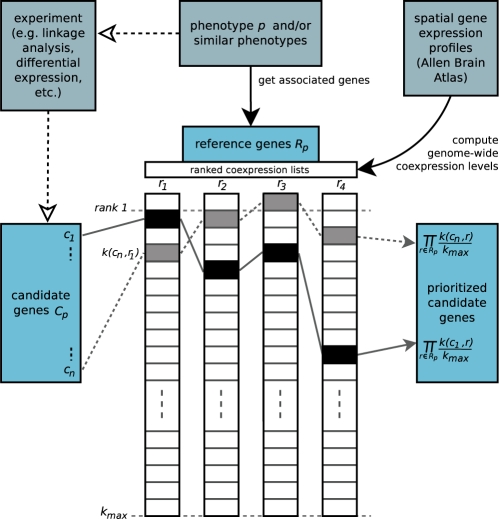

Given a set of candidate genes Cp (e.g. positional candidates from linkage analysis) that have to be prioritized, i.e. ranked according to their probability of being involved in a given phenotype p, the following procedure is applied (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the candidate prioritization method. The procedure is exemplified with two of the hypothetical candidate genes. The list of candidate genes, the phenotype p and the spatial gene expression profiles are considered as given.

First, a set of ‘reference genes’ Rp is selected for the given phenotype. These are genes known to be involved in p and/or similar phenotypes (e.g. via MimMiner, see above).

Then, for each reference gene r ∈ Rp a genome-wide, ranked co-expression list is determined by listing all other genes according to their decreasing co-expression with the reference gene. As a measure of co-expression, we apply the widely used Pearson correlation coefficient.

The rank/position k(c, r) of each candidate gene c ∈ Cp within each of the co-expression lists of the reference genes r is determined, and a relative rank k(c, r)/kmax computed, where kmax is the total number of genes in each co-expression list (all genes but the reference gene r itself).

Each candidate gene is assigned an overall score sc defined as the product of its relative ranks within the reference genes' co-expression lists:

| (1) |

Under the assumption of independence of the correlation coefficients of different gene pairs,1 this score would be equivalent to a P-value of having by chance ranks k(c, r) or better.

Finally, candidate genes are prioritized, i.e. sorted, according to their increasing scores, since lower scores indicate a higher probability of being involved in the given phenotype.

2.7 Leave-one-out

Two large-scale leave-one-out validations were performed: one considering mouse phenotypes from MGD and one considering human Mendelian disorders from OMIM.

For each known gene–phenotype (g–p) pair, a set of reference genes Rp was defined as all genes known to be involved in the given phenotype p (except g itself) and/or all genes associated to similar phenotypes (for human disorders). Then, using gene coordinates obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al., 2002), an artificial locus was constructed on the mouse or human chromosome, respectively, comprising the N genes flanking on both sides of g (containing thus up to 2N+1 genes centered around g). In case of g being close to a chromosome terminal, the number of genes in the artificial locus could also be <2N+1 (but in any case ≥N+1). Three representative sizes N for artificial loci were chosen: 50, 100, and 200 (with a maximum number of 101, 201 and 401 positional candidates, respectively).

Those genes within the artificial locus for which spatial brain expression data was available were considered as candidate genes (simulating an ‘orphan’ locus obtained by linkage analysis or comparable techniques), and the prioritization method was applied as described above. The relative rank/position ℛgrel of the phenotype-causing gene g among the prioritized candidates c ∈ Cp from the artificial locus was recorded:

| (2) |

where ℛg is the rank of g within the prioritized genes and |Cp|≤2N+1 is the number of candidates for which spatial expression data was available.

The analysis, however, was limited to gene–phenotype pairs whose corresponding artificial loci contained at least 50 ‘effective’ candidate genes for which ABA expression profiles were available—one of which was required to be the true phenotype-related gene—since only these can be evaluated and thus prioritized. We reasoned that a lower number of effective candidate genes would introduce an undesired bias by automatically placing the true phenotype-causing gene in higher ranks.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The anatomically comprehensive Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (Lein et al., 2007), is composed of series of ISH images that form layered, 3D gene expression profiles covering the entire adult C57BL/6J mouse brain at a very fine resolution (cellular but not single cell).

Since the notion of co-expression can be effectively exploited for predicting disease genes (Aerts et al., 2006; Ala et al., 2008; Miozzi et al., 2008; Mootha et al., 2003; Rossi et al., 2006), or more in general gene–phenotype relationships, we reasoned that the spatially mapped gene expression provided by the ABA would be of particular interest for predicting the involvement of genes in CNS-related phenotypes.

3.1 Evaluation by leave-one-out

We evaluated the possibility to predict gene–phenotype associations using a leave-one-out procedure (Section 2) that simulates the case where a limited set of candidate genes (e.g. obtained through linkage analysis) is to be ranked according to their relation to a given phenotype.

For this purpose, we used 3D ABA gene expression patterns that report ‘expression energies’ determined from grey-scale values of ISH image intensities, summed over evenly spaced voxels of 200 μm side length (Section 2).

Known gene–phenotype (g–p) relations were processed in leave-one-out tests by constructing artificial loci of varying sizes on the mouse or human chromosome, respectively, followed by scoring of the ‘candidate’ genes lying within these loci against the set of reference genes composed of all other genes known to cause the given phenotype (Section 2). For human disorders also genes known to be involved in similar phenotypes were considered as reference genes.

In contrast to some related work (Aerts et al., 2006), we did not determine a single ‘representative’ reference expression pattern by averaging over the set of reference genes. Especially for the more complex phenotypes, it cannot be expected that candidates are highly co-expressed with all reference genes, questioning the biological meaning of an arbitrarily constructed average reference profile. Instead, we compared the expression of the candidate genes to all single reference genes, such that a significant co-expression with only a subset of the reference genes could in theory already yield a high rank among the prioritized candidates (Section 2).

For each leave-one-out test, the rank of the true phenotype-related gene within the list of prioritized candidates was recorded. Supposing that only the highest ranking candidates would be considered for further study in a laboratory, we verified how often the true phenotype-causing gene was ranked first (ℛg=1), among the top ten (ℛg≤10), and among the upper 10% (ℛgrel≤0.1) of the prioritized list. The corresponding ROC curves can be found in Supplementary Figure S1.

3.2 Mouse phenotypes

A total of 18 389 3D gene expression profiles and 1025 known gene–phenotype pairs for 131 mouse brain- and CNS-related phenotypes (Section 2) were considered for the leave-one-out procedure. As can be seen in Table 1, the procedure yielded for all three locus sizes a significantly higher number of positive results than expected by chance. The number of true phenotype-related genes found among the top 10 candidates, for example, was highly significant (P = 1.38e-11 for N = 50, P = 6.77e-14 for N = 100, and P = 4.79e-09 for N = 200). This suggests that spatial gene expression data from a complex organ, like the mouse brain, can be an important source of information to predict novel gene–phenotype associations. The areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) ranged from 0.547 to 0.562 (see Supplementary Table S4).

Table 1.

Results of the leave-one-out tests

| Organism, phenotypes | N | Candidates (average) | g–p pairs | Ranked first |

Ranked 1st–10th |

Ranked ≤10% |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Exp. | P-value | Obs. | Exp. | P-value | Obs. | Exp. | P-value | ||||

| Mouse | 50 | 85.1 | 860 | 26 | 10 | 1.57e-05*** | 169 | 101 | 1.38e-11*** | 144 | 86 | 5.95e-10*** |

| Mouse | 100 | 160.4 | 877 | 18 | 5 | 1.47e-05*** | 115 | 55 | 6.77e-14*** | 152 | 88 | 1.78e-11*** |

| Mouse | 200 | 298.8 | 880 | 13 | 3 | 1.20e-05*** | 65 | 29 | 4.79e-09*** | 147 | 88 | 5.67e-10*** |

| Human, mol.basis unkn. (%) | 50 | 73.8 | 797 | 16 | 11 | 7.95e-02 | 149 | 108 | 2.64e-05*** | 126 | 80 | 1.80e-07*** |

| Human, mol.basis unkn. (%) | 100 | 137.7 | 844 | 13 | 6 | 9.84e-03** | 105 | 61 | 6.26e-08*** | 132 | 84 | 1.93e-07*** |

| Human, mol.basis unkn. (%) | 200 | 256.6 | 847 | 6 | 3 | 1.16e-01 | 61 | 33 | 4.84e-06*** | 139 | 85 | 5.08e-09*** |

N represents the size of the artificial loci having a maximum of 2N+1 genes. The average numbers of effective candidates with ABA profiles and the numbers of evaluated g–p pairs are shown. The observed and expected numbers of g–p pairs, for which the true phenotype-causing gene g ranks first, among the top 10 and within the best 10% of the prioritized list, is reported along with the corresponding P-values (one-tailed Fisher exact test). Significant P-values are highlighted (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001).

The same procedure was applied to 12 676 microarray gene expression profiles for the mouse brain, extracted from the GNF expression atlas (Su et al., 2004; see Supplementary Methods and Table S1). The results are far less significant than the ones obtained from the Allen Brain Atlas. However, the microarray dataset is much smaller in terms of genes and especially of number of experimental points. Therefore, we cannot draw any firm conclusion on the superiority of spatial gene expression data over microarray data for the identification of disease genes.

3.3 Human disorders

We asked whether spatial expression from the mouse brain would also be helpful when applied to the prediction of human disease genes for Mendelian disorders described in OMIM. We therefore mapped the ABA expression profiles of 14 916 mouse genes to their human homologs and applied the same leave-one-out procedure to known human gene–disease associations. Since the CNS-related OMIM phenotypes can be very detailed and have on average only 1.3 associated disease genes we used MimMiner to extend the sets of reference genes, in order to include also genes involved in similar phenotypes (see Section 2).

We executed the leave-one-out procedure twice: once excluding all known disease genes from the set of reference genes for a given phenotype (relying only on reference genes from similar phenotypes) to simulate disorders that are classified in OMIM as having ‘unknown molecular basis’ (OMIM class: %); and once including all known disease genes, with exception of the gene around which the artificial locus was constructed, to simulate OMIM phenotypes with (at least partly) ‘known molecular basis’ (OMIM class: #). The results for the two cases were almost identical, since similar phenotypes contributed most if not all of the reference genes, even when the molecular basis was known. Therefore, we present here only those regarding the leave-one-out procedure for phenotypes with unknown molecular basis (see Supplementary Table S1 for the results of class #).

As shown in Table 1, the use of spatial expression patterns of the adult mouse brain yields good results even for human CNS-related Mendelian disorders. The number of true phenotype-related genes found among the top 10 candidates, for example, was significant for all locus sizes: P-values obtained were P = 2.64e-05 for N = 50, P = 6.26e-08 for N = 100 and P = 4.84e-06 for N = 200. Non-significant results, for the phenotype-causing gene g ranking first at N = 50 and N = 100, likely depend on a lack of statistical power, since their fold-enrichments are similar to those obtained for g ranking among the top 10 and among the best 10%. AUCs ranged from 0.549 to 0.571 for human disorders (see Supplementary Table S4).

3.4 Case study: XLMR

As a specific case study, we selected XLMR. This disorder is particularly challenging, if considered that 90 genes on the X chromosome are known to be associated to some form of intellectual disability and that a similar number probably remains to be identified (Cécz et al., 2009). We used as a set of hypothetical candidate genes the 718 genes on chromosome X whose coding exons had recently been resequenced by Tarpey et al. (2009) in a search for the causes of XLMR in 208 affected families. Of these genes, we could map 471 to ABA expression profiles from the mouse brain for further evaluation. A total of 73 (15.5%) of these mapped genes were known to be involved in XLMR (including two, SYP and CASK, of the three novel XLMR genes that had been discovered by Tarpey et al.).

3.5 Evaluation

For a first evaluation, none of the 471 resequenced candidates on chromosome X were included among the reference genes, thus pretending XLMR to be a disorder with unknown molecular basis. The reference genes were instead selected from similar phenotypes. As the number of reference genes was still very high (several hundreds) with the standard 0.4 cutoff, we increased the threshold of the MimMiner similarity score to 0.5, obtaining a total of 58 reference genes with mapped ABA expression data.

We ranked the 471 candidates using our prioritization procedure. In spite of the restrictive assumption of XLMR being a disorder with unknown molecular basis and the fact that we relied on gene expression from the mouse brain to evaluate candidates for a human disease, the 47 (10%) best scoring candidate genes (see Supplementary Table S2) contained 13 confirmed XLMR genes (P = 0.0177). Most notably, the best scoring gene (BRWD3) and the gene at rank 3 (SYP), shown in Table 2, are both known XLMR genes, the latter having only recently been discovered by the mentioned resequencing study (Field et al., 2007; Tarpey et al., 2009). Therefore, without a priori considering known XLMR genes, our procedure would have suggested at least two valid candidates among the first three of the prioritized list.

Table 2.

Best 20 candidates of the prioritization (evaluation via similar phenotypes) of the chromosome X genes resequenced by Tarpey et al. (2009) (see also Supplementary Table S2)

| Rank | Gene | Entrez ID | Disorder | Mut. score | Score sc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BRWD3 | 254 065 | XLMR | 2.86 | 7.16e-78 |

| 2 | IRAK1 | 3654 | – | 1.94 | 1.84e-71 |

| 3 | SYP | 6855 | XLMR | − | 8.97e-69 |

| 4 | BIRC4 | 331 | other | 37.04 | 4.28e-68 |

| 5 | MAGED1 | 9500 | – | 5.14 | 5.63e-68 |

| 6 | MORF4L2 | 9643 | – | − | 3.37e-66 |

| 7 | ZNF280C | 55 609 | – | − | 5.07e-65 |

| 8 | SYN1 | 6853 | XLMR | − | 1.15e-64 |

| 9 | CXorf6 | 10 046 | other | 12.00 | 1.19e-64 |

| 10 | ATP6AP2 | 10 159 | XLMR | − | 2.70e-64 |

| 11 | HCFC1 | 3054 | – | 27.82 | 1.65e-61 |

| 12 | PJA1 | 64 219 | – | 2.44 | 1.82e-61 |

| 13 | NGFRAP1 | 27 018 | – | − | 1.91e-61 |

| 14 | FAM50A | 9130 | – | 11.62 | 5.63e-61 |

| 15 | HUWE1 | 10 075 | XLMR | 46.75 | 1.62e-60 |

| 16 | GRIA3 | 2892 | XLMR | 13.00 | 1.14e-59 |

| 17 | PIGA | 5277 | other | − | 3.24e-59 |

| 18 | OGT | 8473 | – | 15.90 | 4.15e-59 |

| 19 | GNL3L | 54 552 | – | 22.49 | 1.68e-58 |

| 20 | WDR40C | 340 578 | – | 0.22 | 3.35e-58 |

Associations to disorders and mutation scores are as reported by Tarpey et al. Mutation scores reflect the conservation scores at missense positions and are summed over the single missense mutations found for each gene. Genes in bold face overlap with those in Table 3.

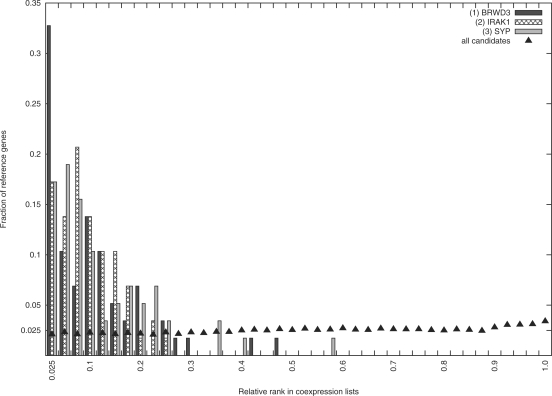

Figure 2 illustrates that the three best candidates (BRWD3, IRAK1 and SYP) rank significantly higher in the co-expression lists of the 58 reference genes, compared to the average rankings of all 471 candidates. BRWD3, for example, ranks among the 2.5% most co-expressed genes for one third of the references genes (P = 1.34e-16), SYP among the 7.5% most co-expressed genes for over half of the reference genes (P = 6.276e-19), and IRAK1 among the 25% most co-expressed genes for all reference genes (P = 1.20e-35). In contrast, the distribution of the relative ranks of all candidates is, as expected, close to a uniform distribution.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of relative ranks k(c, r)/kmax of the three best XLMR candidates (within the co-expression lists of the 58 references genes), compared to the distribution of relative ranks of all 471 candidates. Data points represent bins of width 0.025.

3.6 Prediction

Since we were able to ‘rediscover’ several known XLMR genes (Table 2) we used the same pipeline for predicting novel candidate genes based on current knowledge of causes of XLMR. For this purpose, we considered all 73 resequenced XLMR genes for which ABA expression profiles were available as reference genes (without including genes involved in similar phenotypes) and considered only the remaining 398 resequenced genes as candidates. The 20 best scoring candidates are shown in Table 3 (see Supplementary Table S3 for the best 10%).

Table 3.

Best 20 candidates of the prioritization (prediction via true XLMR genes) of the chromosome X genes resequenced by Tarpey et al. (2009) (see also Supplementary Table S3)

| Rank | Gene | Entrez ID | Disorder | Mut. score | Score sc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MORF4L2 | 9643 | – | − | 5.09e-99 |

| 2 | PJA1 | 64219 | – | 2.44 | 7.70e-97 |

| 3 | ZNF280C | 55609 | – | − | 1.91e-93 |

| 4 | MAGED1 | 9500 | – | 5.14 | 1.55e-91 |

| 5 | MAGEE1 | 57692 | – | 2.04 | 1.60e-85 |

| 6 | BIRC4 | 331 | other | 37.04 | 1.02e-84 |

| 7 | GRIPAP1 | 56850 | – | 8.17 | 3.13e-82 |

| 8 | CXorf6 | 10046 | other | 12.00 | 3.75e-81 |

| 9 | GNL3L | 54552 | – | 22.49 | 4.07e-81 |

| 10 | FAM50A | 9130 | – | 11.62 | 7.72e-81 |

| 11 | PGRMC1 | 10857 | – | 9.70 | 8.65e-81 |

| 12 | GPM6B | 2824 | – | − | 4.12e-79 |

| 13 | IRAK1 | 3654 | – | 1.94 | 8.19e-79 |

| 14 | HCFC1 | 3054 | – | 27.82 | 1.28e-78 |

| 15 | PIGA | 5277 | other | − | 1.65e-78 |

| 16 | RPS4X | 6191 | – | − | 4.97e-78 |

| 17 | REPS2 | 9185 | – | − | 2.81e-77 |

| 18 | ARMCX2 | 9823 | – | − | 1.67e-75 |

| 19 | DRP2 | 1821 | – | 41.79 | 3.64e-74 |

| 20 | MED14 | 9282 | – | 9.54 | 1.41e-73 |

Associations to disorders and mutation scores are as reported by Tarpey et al. Mutation scores reflect the conservation scores at missense positions and are summed over the single missense mutations found for each gene. Genes in bold face overlap with those in Table 2.

The overlap between the two prioritizations–-taking XLMR as a disorder with unknown molecular basis or relying instead on consolidated knowledge–-is striking: 11 out of 14 of the best ranking non-XLMR genes with the first prioritization (evaluation) have also been found among the top 20 of the prediction via true XLMR genes (P = 6.62e-14). We must emphasize the fact that the two sets of reference genes were completely distinct and only related via the concept of phenotype similarity. This strongly suggests that the results are robust and that we can therefore consider the best ranking genes of the two prioritizations as promising novel candidates for XLMR.

Interestingly, missense mutations of highly conserved residues were found by Tarpey et al. in some of our candidates (Tables 2 and 3), although these mutations could not, in many cases, be unambiguously linked to XLMR. Nevertheless, our results suggest that at least some of them may be the true cause of XLMR.

3.7 Novel candidates

It is important to notice that most of our top scoring genes are not very obvious candidates for a role in intellectual disability, on the basis of their functional characterization. Indeed, for many of them, no information at all is available from the literature. Moreover, in the case of BIRC4, HCFC1, CXorf6, PGRMC1 and PIGA, the genes have been characterized for their involvement in diseases or disease-related processes not specifically connected to the CNS.

However, some interesting remark can be made in other cases. For instance, GRIPAP1, also known as GRASP-1, is a neuronally enriched protein that interacts with the AMPA-type glutamate receptor/GRIP and acts as a scaffold for the JNK signalling pathway (Ye et al., 2007), that may be involved in mental retardation downstream of the IL1 receptor (Pavlowsky et al., 2010). Interestingly, IRAK1 is another component of the IL1R-JNK pathway (Vig et al., 1999) and has been recently found to be upregulated in a mouse model of Rett syndrome (Urdinguio et al., 2008). The p75 neurotrophin receptor-mediated programmed cell death pathway, that may play an important role in memory and attentional processes by regulating survival of the cholinergic neurons (Niewiadomska et al., 2010), is also well represented among our candidates by NGFRAP1 and MAGED1 (Bertrand et al., 2008); and in a recent report MAGED1 has been also found to functionally interact with PJA1 (Sasaki et al., 2002). Finally, DRP2 and MAGEE1 are components of the dystrophins/dystroglycans complex (Albrecht and Froehner, 2004; Jin et al., 2007), whose dysfunction results in a high incidence of intellectual disability and psychiatric disorders (Waite et al., 2009), besides to muscular dystrophy. The very high conservation score of the missense mutations of DRP2 found in XLMR families (Tarpey et al., 2009) is particularly intriguing. Indeed, although the complete inactivation of the gene in mice has revealed that it plays a specific role in peripheral myelination (Sherman et al., 2001), a previous report showed that the encoded protein is associated to the post-synaptic density, a neuronal structure strongly involved in learning and memory processes (Roberts and Sheng, 2000). On this basis, it is conceivable that subtle mutations of some of the mentioned genes may contribute to intellectual disability in humans.

4 CONCLUSION

Taken together, our results are very promising, demonstrating the value of high-resolution spatial gene expression data for the purpose of candidate gene prioritization and disease-gene prediction.

We have shown that spatial expression data from the mouse brain can be successfully used to predict not only genes involved in mouse phenotypes, but also genes involved in human CNS-related disorders. The robustness of our results led us to suggest novel candidates for X-linked mental retardation.

Unfortunately, 3D expression data remain an exception, and many potentially powerful applications (such as a hypothetical ‘differential spatial expression’ of case versus control samples) are currently impossible, but as our study hopefully illustrates, further effort to advance relevant technologies and experimental procedures will not be wasted. The ongoing preparation of the Allen Human Brain Atlas, scheduled to be completed in 2013, promises an additional rich source of information for disease gene prediction. The proof-of-concept that we present here, can be understood as a pioneer study towards a more direct analysis of spatial co-expression in the human brain.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Han Brunner and Martin Oti of the Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences, The Netherlands, for providing us with software and precious help regarding MimMiner (van Driel et al., 2006).

Funding: Italian Association for Cancer Research (to P.P.); Regione Piemonte (to P.P., F.D.C.); FIRB-Italbionet program of the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research; Fondazione San Paolo (to F.D.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1This assumption does not hold due to the biological interdependence of gene regulation. We mention it here only to underline the rationale of the scoring procedure we have chosen.

REFERENCES

- Aerts S, et al. Gene prioritization through genomic data fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:537–544. doi: 10.1038/nbt1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ala U, et al. Prediction of human disease genes by human-mouse conserved coexpression analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht DE, Froehner SC. DAMAGE, a novel alpha-dystrobrevin-associated MAGE protein in dystrophin complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7014–7023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberger J, et al. McKusick's Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D793–D796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand MJ, et al. NRAGE, a p75NTR adaptor protein, is required for developmental apoptosis in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1921–1929. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, et al. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargill M, et al. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:231–238. doi: 10.1038/10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cécz J, et al. The genetic landscape of intellectual disability arising from chromosome X. Trends Genet. 2009;25:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, et al. A genome-scale map of expression for a mouse brain section obtained using voxelation. Physiol. Genomics. 2007;30:313–321. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00287.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert-Buck MR, et al. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, et al. Mutations in the BRWD3 gene cause X-linked mental retardation associated with macrocephaly. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:367–374. doi: 10.1086/520677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg J, Propping P. A similarity-based method for genome-wide prediction of disease-relevant human genes. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl. 2):S110–S115. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_2.s110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, et al. The dystrotelin, dystrophin and dystrobrevin superfamily: new paralogues and old isoforms. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AR, et al. The Allen Brain Atlas: 5 years and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:821–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage K, et al. A human phenome-interactome network of protein complexes implicated in genetic disorders. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:309–316. doi: 10.1038/nbt1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein ES, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, et al. Study of gene function based on spatial co-expression in a high-resolution mouse brain atlas. BMC Syst. Biol. 2007;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Bigas N, Ouzounis CA. Genome-wide identification of genes likely to be involved in human genetic disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3108–3114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis ER. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends Genet. 2007;24:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miozzi L, et al. Functional annotation and identification of candidate disease genes by computational analysis of normal tissue gene expression data. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha VK, et al. Identification of a gene causing human cytochrome c oxidase deficiency by integrative genomics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:605–610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242716699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomska G, et al. The cholinergic system, nerve growth factor and the cytoskeleton. Behav. Brain Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.024. [Epub ahead of print, doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.024] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oti M, et al. Predicting disease genes using protein-protein interactions. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:691–698. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlowsky A, et al. A postsynaptic signaling pathway that may account for the cognitive defect due to IL1RAPL1 mutation. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Iratxeta C, et al. Association of genes to genetically inherited diseases using data mining. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:316–319. doi: 10.1038/ng895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RG, Sheng M. Association of dystrophin-related protein 2 (DRP2) with postsynaptic densities in rat brain. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:674–685. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, et al. TOM: a web-based integrated approach for identification of candidate disease genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W285–W292. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, et al. A RING finger protein Praja1 regulates Dlx5-dependent transcription through its ubiquitin ligase activity for the Dlx/Msx-interacting MAGE/Necdin family protein, Dlxin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:22541–22546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers EW, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D5–D16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert W, et al. Analyzing proteome topology and function by automated multidimensional fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1270–1278. doi: 10.1038/nbt1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DL, et al. Specific disruption of a schwann cell dystrophin-related protein complex in a demyelinating neuropathy. Neuron. 2001;30:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckli M, et al. Imaging mass spectrometry: a new technology for the analysis of protein expression in mammalian tissues. Nat. Med. 2001;7:493–496. doi: 10.1038/86573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su AI, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey PS, et al. A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:535–543. doi: 10.1038/ng.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin N, et al. Integration of text- and data-mining using ontologies successfully selects disease gene candidates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1544–1552. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner FS, et al. POCUS: mining genomic sequence annotation to predict disease. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R75. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-11-r75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urdinguio RG, et al. Mecp2-null mice provide new neuronal targets for Rett syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Driel MA, et al. A text-mining analysis of the human phenome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:535–542. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig E, et al. Modulation of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1-dependent NF-kappaB activity by mPLK/IRAK. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13077–13084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite A, et al. The neurobiology of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex. Ann. Med. 2009;41:344–359. doi: 10.1080/07853890802668522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B, et al. GRASP-1 is a neuronal scaffold protein for the JNK signaling pathway. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4403–4410. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.