Abstract

The plasmid-encoded small multidrug resistance pump from S. aureus transports a variety of quaternary ammonium and other hydrophobic compounds, enhancing the bacterial host’s resistance to common hospital disinfectants. The protein folds as a homo-dimer of four transmembrane helices each, and appears to be fully functional only in lipid bilayers. Here we report the backbone resonance assignments and implied secondary structure for 2H13C15N Smr reconstituted into lipid bicelles. Significant changes were observed between the chemical shifts of the protein in lipid bicelles compared to those in detergent micelles.

Keywords: MDR, Smr, NMR, Bicelle, Membrane protein

Biological context

Bacteria have developed several methods to resist the lethal effects of antibiotics. The broadest spectrum resistance results from the action of Multi-Drug Resistance pumps (MDRs), which extrude a range of compounds of quite diverse chemical structure. Most Small Multidrug Resistance transporters (SMRs) are homodimeric membrane proteins of ~ 110 residues per monomer. Smr, formerly called QacC, was the first SMR family member identified. It was originally cloned and sequenced from plasmids obtained from clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates that were resistant to disinfectants (Littlejohn et al. 1991). Shortly thereafter, a chromosomal Escherichia coli homolog (EmrE) was identified. At present, this family of multidrug transporters is known to have over 200 members that are found in a wide range of microbes (Schuldiner 2009). While EmrE is the best characterized family member, we have chosen to focus on the S. aureus SMR, since it has been found in a range of disinfectant resistant bacterial isolates in humans and livestock, and is thus a clinically important multidrug transporter.

SMRs are proton-drug antiporters that use a proton gradient to drive the efflux of a wide range of hydrophobic cationic compounds. Both Smr (Grinius and Goldberg 1994) and EmrE were overexpressed, purified, reconstituted into liposomes, and shown to transport a variety of drugs in the presence of a proton gradient. Both proteins were shown to fold as four transmembrane helices. A single glutamate in the first transmembrane helix (Glu13 in Smr and Glu14 in EmrE) is the only residue absolutely essential for substrate binding and transport (Grinius and Goldberg 1994), which involves the exchange of cationic drug (or neutral drug plus a cation) for protons at the pair of glutamates in the homodimer. With their small size and simple architecture, SMRs were expected to be ideal proteins for understanding the essentials of multidrug transport. However, this has proven to be much more difficult than anticipated, with conflicting and controversial findings. Briefly (reviewed in (Schuldiner 2009; Korkhov and Tate 2009)) initial topology mapping placed the N- and C-termini of Smr and EmrE on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, and cross-linking and spin label EPR experiments supported a “parallel” dimer in which both monomers had the same membrane orientation. Shortly thereafter, a cryoEM projection map of EmrE (Ubarretxena-Belandia et al. 2003) was interpreted as supporting an inverted dimer. Von Heijne’s group showed that by manipulating the charged residues in the loops and termini of EmrE it could be coaxed into either membrane orientation (Rapp et al. 2007), and their initial data indicated that only a mix of the two orientations was functional—although subsequent results indicate that the parallel dimer is, in fact, functional (Mchaourab et al. 2008). Finally, a pair of revised crystal structures (Chen et al. 2007) of EmrE in nonyl-glucoside detergent micelles showed two very different folds for the protein in the presence and absence of substrate, and the substrate bound form was modeled as an inverted dimer. Functional studies have shown that SMRs only retain native ligand affinity in long chain maltoside detergent micelles and lipid bilayers (Poget et al. 2007). Hence we are structurally characterizing Smr reconstituted into functional form in lipid bicelles in order to resolve these uncertainties and understand how small MDRs function. The chemical shifts reported here for the protein in bicelles differ significantly from those observed for the protein in lysolipid micelles (Poget et al. 2006).

Materials and experiments

Sample preparation

Smr from S. aureus was overexpressed and purified as described by Krueger-Koplin et al. (2004), using M63 media prepared with 15NH4Cl, 2H13C-glucose and 99.8% D2O. The protein was reconstituted into lipid bicelles as previously described (Poget et al. 2007), using 10.5 mM 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DHPS), 198.5 mM 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DHPC), and 83.5 mM 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), for a final ratio of q = 0.4 for long chain to short chain lipids, in 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.8), 0.05% NaN3 and 10% D2O. The addition of 5 mM 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DMPE-DTPA) (Prosser et al. 1998) to the lipid mixture and the lowering of the experimental temperature from 320 to 315.5 K were found to extend the sample half-life from the previous 7 days to over 28 days. The final protein concentration was 1 mM (dimer) 2H13C15N uniformly labeled Smr.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired at 315.5 K on Bruker Avance spectrometers (operating at a nominal frequency of 700, 800 or 900 MHz) equipped with a triple resonance (1H, 13C, 15N) TCI or TXI cryogenic probe including Z-axis pulse field gradients. The overall correlation time for Smr in q = 0.4 bicelles was estimated to be 53 ns using the TRACT method (Lee et al. 2006). Sequence specific resonance assignments were obtained by combining the data from 2D CACO, 3D 15N NOESY–TROSY (τmix = 80 ms) and the following 3D TROSY, deuterium decoupled, gradient sensitivity enhanced triple resonance experiments: HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA and HN(CA)CB (Yamazaki et al. 1994). The triple resonance pulse sequences used were modified from the standard Bruker non-deuterium decoupled pulse sequences to include the deuterium decoupling and an extra gradient in the C–N reverse INEPT period to improve lipid buffer suppression. All spectra were processed using NMRpipe/NMRDraw (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed using CCPN Analysis (Vranken et al. 2005). Chemical shifts were referenced to DSS in the samples (Wishart et al. 1995).

Extent of assignments and data deposition

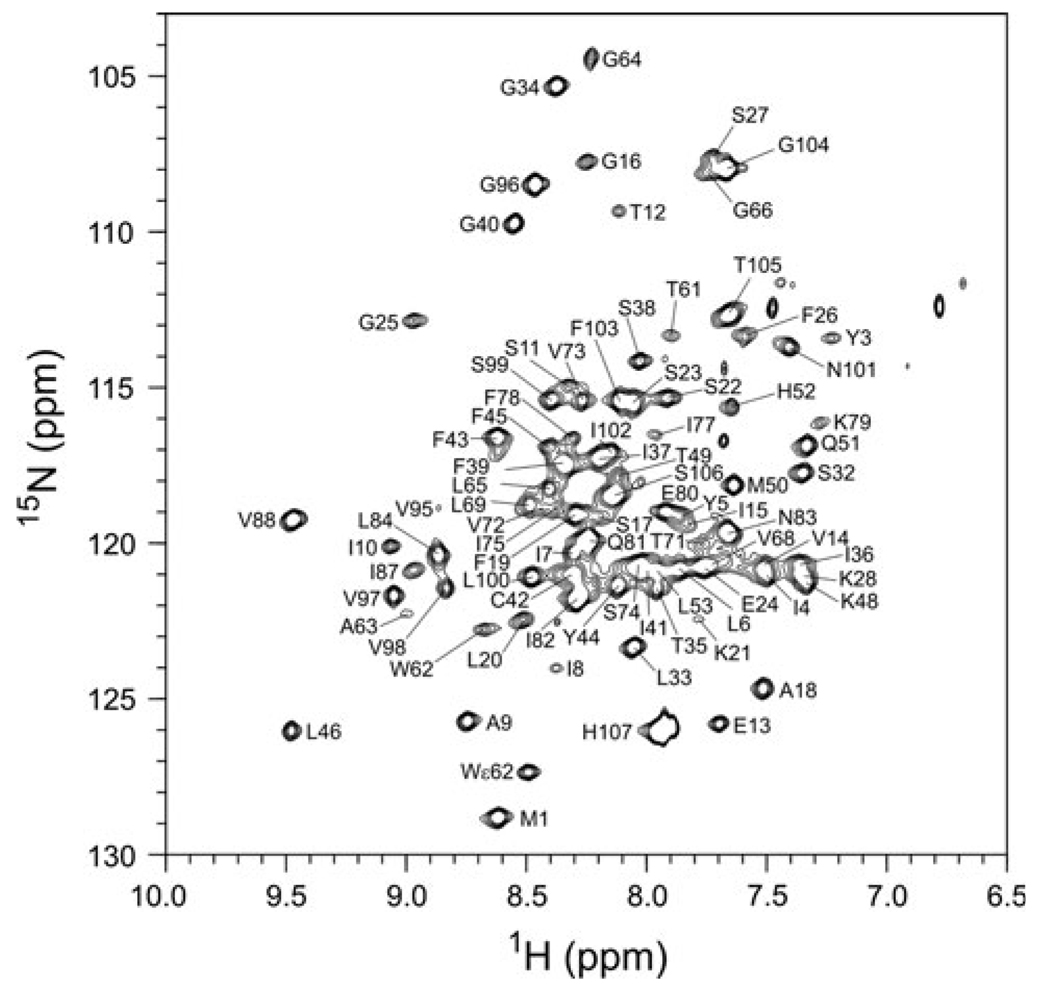

Analysis of the experiments allowed identification and the sequence-specific assignments for 85 out of the 104 Smr (107 less 3 prolines) backbone 15N and amide proton resonances. Definitive assignments have not been obtained for F29, I30, S47, L55-A60, L67, T70, I76, T86, S89-I94—the resonances for a number of residues disappear on lowering the temperature from 320 K. Figure 1 shows an assigned 2D 13C-decoupled 1H–15N TROSY spectrum of [2H, 13C, 15N] Smr at pH 6.8, recorded at a 1H frequency of 800 MHz. From the assigned amide resonances, we were able to obtain 88, 61 and 84% of the Cα, Cβ and CO chemical shifts, respectively. The backbone 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts of Smr have been deposited at BioMagResBank under accession number 16783. These Smr backbone assignments will permit mapping the binding sites of its many transport substrates.

Fig 1.

Assigned 2D 13C-decoupled 1H–15N TROSY spectrum of [2H, 15N, 13C]-labeled Smr recorded on a 800 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer at 315.5 K

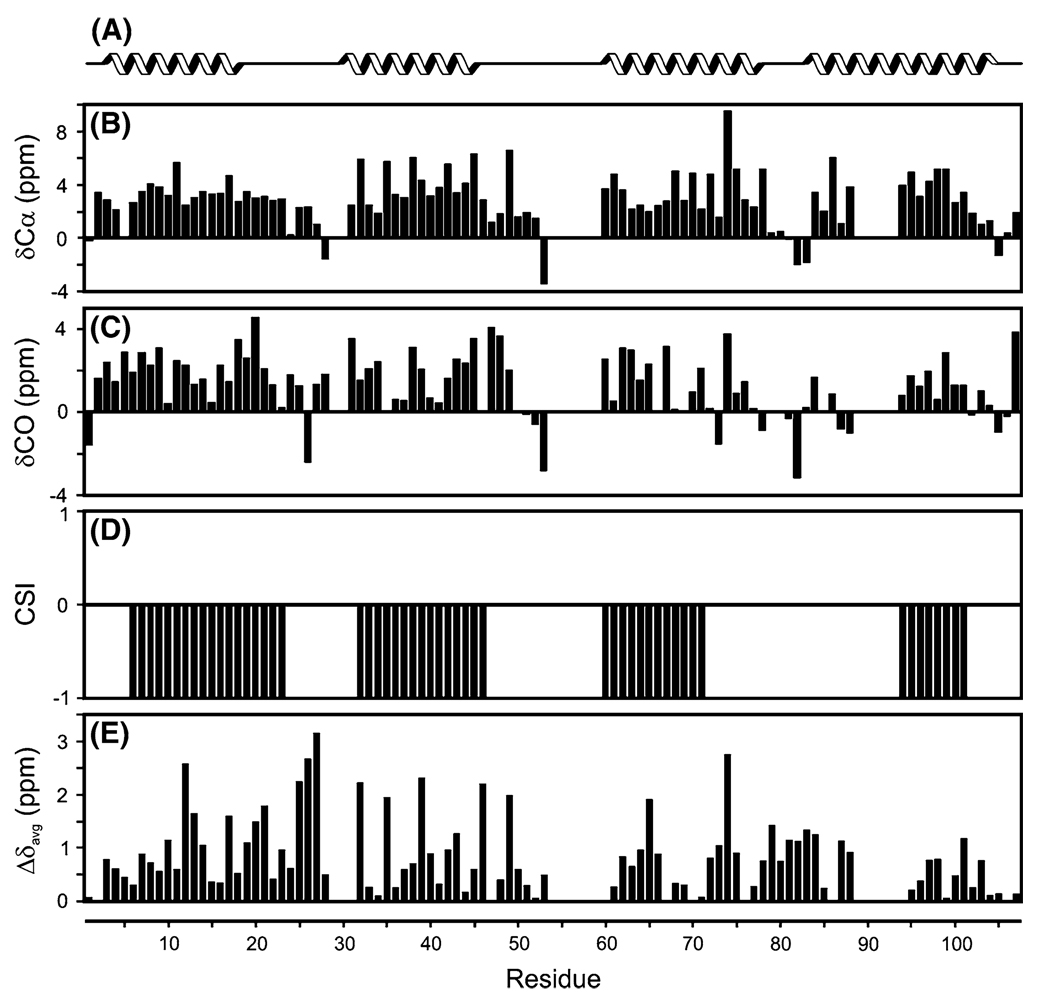

The secondary structure of Smr was predicted using the chemical shift difference method between measured values and random-coil values of Cα, Cβ and CO. The Cα and Cβ shifts were corrected for the deuterium effect (Venters et al. 1996). Figure 2 shows the secondary structure prediction from TMHMM (Krogh et al. 2001), along with the secondary chemical shifts and consensus CSI (Wishart and Sykes 1994) results. Analysis of the secondary chemical shift data suggest that Smr contains 4 alpha helices; residues 6–23, 32–46, 60–71 and 94–101. The analysis is in good agreement with the TMHMM prediction, apart from helix 4 that is under-predicted by the secondary chemical shifts probably because of the missing assignments for residues 89–94. The average differences in amide proton and nitrogen chemical shifts for Smr in lipid bicelles versus lysolipid detergent micelles are presented in Fig. 2e. Changes are apparent throughout the protein, with the largest differences found in the first three transmembrane helices and the two loops connecting them.

Fig 2.

Chemical shift deviations and secondary structure predictions for Smr. a TMHMM transmembrane helix prediction. Deviations from random coil shifts for b δCα and c δCO, yield the CSI plot shown in d. The average amide chemical shift differences, (((Δδ1H)2 + (Δδ15N/5)2)/2)1/2, for Smr in bicelles vs. the protein in LPPG detergent micelles (e)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM072085. Many of the NMR experiments were performed at the New York Structural Biology Center, which is a STAR center supported by the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research; its 900 MHz spectrometers were purchased with funds from NIH, USA, the Keck Foundation, New York State, and the NYC Economic Development Corporation.

Contributor Information

Sébastien F. Poget, Chemistry Department, College of Staten Island, 2800 Victory Boulevard, Staten Island, NY 10314, USA

Richard Harris, Biochemistry Department, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

Sean M. Cahill, Biochemistry Department, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 10461, USA

Mark E. Girvin, Biochemistry Department, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 10461, USA mark.girvin@einstein.yu.edu

References

- Chen YJ, et al. X-ray structure of EmrE supports dual topology model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18999–19004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709387104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfiefer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinius LL, Goldberg EB. Bacterial multidrug resistance is due to a single membrane protein which functions as a drug pump. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29998–30004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkhov VM, Tate CG. An emerging consensus for the structure of EmrE. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(Pt 2):186–192. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908036640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger-Koplin RD, et al. An evaluation of detergents for NMR structural studies of membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:43–57. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000012875.80898.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Hilty C, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Effective rotational correlation times of proteins from NMR relaxation interference. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn TG, et al. Structure and evolution of a family of genes encoding antiseptic and disinfectant resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Gene. 1991;101:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90224-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mchaourab HS, et al. Role of sequence bias in the topology of the multidrug transporter EmrE. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7980–7982. doi: 10.1021/bi800628d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poget SF, Krueger-Koplin ST, Krueger-Koplin RD, Cahill SM, Chandra Shekar S, Girvin ME. NMR assignment of the dimeric S. aureus small multidrug-resistance pump in LPPG micelles. J Biomol NMR. 2006;36 suppl 1:10. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-5346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poget SF, Cahill SM, Girvin ME. Isotropic bicelles stabilize the functional form of a small multidrug-resistance pump for NMR structural studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2432–2433. doi: 10.1021/ja0679836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser RS, Volkov VB, Shiyanovskaya IV. Novel chelate-induced magnetic alignment of biological membranes. Biophys J. 1998;75:2163–2169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77659-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp M, et al. Emulating membrane protein evolution by rational design. Science. 2007;315:1282–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1135406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner S. EmrE, a model for studying evolution and mechanism of ion-coupled transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Baldwin JM, Schuldiner S, Tate CG. Three-dimensional structure of the bacterial multidrug transporter EmrE shows it is an asymmetric homodimer. EMBO J. 2003;22:6175–6181. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venters RA, Farmer BT, II, Fierke CA, Spicer LD. Characterizing the use of perdeuteration in NMR studies of large proteins: 13C, 15N and 1H assignments of human carbonic anhydrase II. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:1101–1116. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Sykes BD. The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, Markley JL, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Lee W, Arrowsmith CH, Muhandiram DR, Kay LE. A suite of triple resonance NMR experiments for the backbone assignment of 15N, 13C, 2H labeled proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:11655–11666. [Google Scholar]