Abstract

Objective

To determine baseline proportion of emergency physicians with favorable attitudes and beliefs toward IV tPA use in a cohort of randomly selected Michigan hospitals.

Methods

278 emergency physicians from 24 hospitals were surveyed. A confidential, self-administered, pilot-tested survey assessing demographics, practice environment, attitudes and beliefs regarding tPA use in stroke was used. Main outcome measures assessed belief in legal standard of care, likelihood of use in ideal setting, comfort in use without a specialist consultation and belief that science on tPA use is convincing. OR with robust 95% CI (adjusted for clustering) were calculated to quantify the association between responses and physician- and hospital-level characteristics.

Results

199 surveys completed (gross response rate 71.6%). 99% [95% CI: 97.8 to 100] indicated use of tPA in eligible patients represented either acceptable or ideal patient care. 27% [95% CI: 21.7 to 32.3] indicated use of tPA represented a legal standard of care. 83% [95% CI: 78.5 to 87.5] indicated they were “likely” or “very likely” to use tPA given an ideal setting. When asked about using tPA without a consultation, 65% [95% CI: 59.3 to 70.7], indicated they were uncomfortable. 49% [95% CI: 43.0 to 55.0] indicated the science regarding use of tPA in stroke is convincing, with 30% remaining neutral. Characteristics associated with favorable attitudes included: non-emergency medicine board certification; older age and a smaller hospital practice environment.

Conclusions

In this cohort, emergency physician attitudes and beliefs toward IV tPA use in stroke are considerably more favorable than previously reported.

Keywords: Stroke, Emergency medicine, Attitude, Belief, Thrombolytic Therapy

Background

Currently, 1 to 3 percent of stroke patients in community settings receive intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke.1–6 Prior research suggests substantial improvement in treatment rates is possible.1, 3, 7, 8 In order to enhance acute treatment, emergency departments - with key triage, evaluation and management responsibilities - have been identified as a critical component in the Stroke Chain of Survival and Recovery.9

Prior reports suggest emergency physicians are resistant to the use of tPA in stroke. A 2005 survey of members of the American College of Emergency Medicine found 40% of respondents were either “unlikely” or “uncertain” to use tPA even in the ideal setting (defined as CT scanner availability, neuroradiology and neurology support, administrative support, appropriate candidate, etc.).10 No professional emergency medicine organization has endorsed the use of tPA in stroke.

If broad emergency physician resistance to tPA use is confirmed, it represents a substantial barrier to increasing acute stroke treatment in the community setting. The objective of this survey was to determine the baseline proportion of emergency physicians with favorable attitudes and beliefs toward the use of tPA in a cohort of practicing emergency physicians from a broad variety of hospital environments in Michigan.

Materials and Methods

Survey Development

This survey was developed as part of the ongoing INSTINCT Stroke Trial (INcreasing Stroke Treatment through INterventional behavior Change Tactics; NIH/NINDS R01NS050372). We used a confidential, self-administered, self-reported, survey assessing emergency physician demographics, practice environment, attitudes and beliefs regarding tPA use in stroke.

The survey was iteratively pilot tested on samples of emergency physicians from hospitals not participating in the study. Pilot testing focused on length, validity, question design, and implementation using an on-line survey system (see Appendix for detail). The University of Michigan and local IRBs approved the INSTINCT trial and its survey.

Selection of Participants

The INSTINCT trial is a multi-center, cluster-randomized, controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a barrier assessment and educational intervention to increase appropriate tPA use in Michigan community hospitals. The unit of randomization was the hospital. Since emergency physicians at the participating hospitals formed the survey cohort, the hospital selection process for the INSTINCT trial is reviewed here.

We selected all acute care hospitals in the lower peninsula of Michigan for potential inclusion in the INSTINCT Trial. Hospitals were excluded if they had > 100,000 emergency department visits, were affiliated with the University of Michigan emergency medicine residency program, had < 100 stroke discharges annually as determined from Michigan Hospital Association data, or were self-identified in 2003 as an academic comprehensive stroke center.

These exclusions allowed focus on the unit of interest – acute care community hospitals. The exclusion of hospitals in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan was made for travel and budget considerations. Small hospitals with less than 100 stroke discharges per year were excluded to ensure an adequate number of treatable strokes for the INSTINCT Trial.

From this available pool of hospitals (n = 61), a single index hospital was randomly selected. Once a hospital was selected, all adjacent hospitals within 15 miles were excluded from the selection pool in order to provide geographic separation between sites and prevent cross-contamination between hospital staffs in the INSTINCT Trial.

From the remaining hospital pool, a match for the selected index hospital was chosen from those hospitals within ± 20% of the index hospital’s annual stroke admissions. All hospitals within 15 miles of the match were then excluded from the selection pool as well. This pair of hospitals, matched on stroke admissions and geographically separated, was then added to the final cohort. This process was repeated until 12 pairs (24 hospitals) were selected. Following selection, each hospital and their corresponding emergency department was contacted regarding participation and a site principal investigator recruited.

Of the original 24 hospitals identified, four declined participation in the study. This required selection of an additional five hospitals, using the process above, to fill the remaining four matches. This comprised the final hospital cohort. Site principal investigators identified all emergency physicians at these 24 hospitals as of January 1, 2007 and provided contact information for each (email/phone) at their respective facilities. Primary pediatric emergency physicians were excluded from the survey cohort as tPA is not approved in patients less than 18 years of age. Resident physicians were also excluded. This formed the final baseline survey cohort of 278 emergency physicians.

Survey Administration

The 278 emergency physicians were surveyed beginning January 1, 2007, prior to any INSTINCT-related educational or system interventions. The survey was administered via a secure, web-based, system (SurveyMonkey.com©). Physicians preferring paper copies were sent surveys with a stamped return envelope. Data quality and logic checks were built into the reporting system and completed for every returned survey. The staff contacted responding physicians to clarify ambiguous responses.

Each individual was contacted up to three times to complete the consent and survey (either online or paper). Non-responders were then contacted by phone or additional email, and offered the survey by phone interview, internet or paper. For continued non-responders, the local site principal investigator was contacted and asked to personally contact them and provide a copy of the survey. Each hospital’s emergency physician group was allocated one $50 incentive to be awarded by random selection following completion of the survey.

Hospital Characteristics

Site investigators at each hospital provided detailed baseline demographic information regarding their respective hospitals, emergency departments and availability of stroke resources as part of the INSTINCT Trial. A standard form was used; complete data was obtained from all participating hospitals. We therefore were able to evaluate associations of practice environment as well as demographic factors (education, board certification, and years since graduation, etc.) with emergency physician beliefs about and attitudes toward tPA use.

Outcome Measures

The main outcome measures were the proportion of emergency physicians who believed the use of tPA in eligible stroke patients represented:

the legal standard of care

the proportion of emergency physicians likely to use tPA in the ideal situation

the proportion of emergency physicians defining themselves as comfortable administering tPA to a patient without a consultation from a neurologist or stroke specialist

the proportion of emergency physicians who agree that the existing science on tPA use in stroke is convincing

In addition, the proportions of emergency physicians who felt that tPA use represented acceptable or ideal patient care, felt a telephone consultation was sufficient prior to treatment, and those identifying liability for tPA use (or non-use) as a major concern were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Summaries of the data were obtained using percentages and means as appropriate. Unadjusted rates for the four main outcomes above were obtained. In this, a positive response was taken as either of the two responses most favorable to use of tPA in each case. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to quantify the association between these responses and individual characteristics of the respondents and their practice environment. The confidence intervals were based on robust standard errors – standard errors which are adjusted for the effects of clustering. To accomplish this, we used a logistic regression model and methods based on generalized estimating equations (GEE) to allow for the clustered structure of the trial and the potential correlations among the responses of physicians within the same hospital.11

These same methods were used in multivariate regression analyses to verify the association between a single explanatory variable and the response variable when controlling for one or more other explanatory variables. The following physician-level explanatory variables were included in the model: board certification in emergency medicine, completion of emergency medicine residency, year of medical school graduation (divided into approximate quartiles), gender, prior participation in tPA treatment and race (white versus non-white). Additionally, the following hospital level explanatory variables were included: 2007 ED volume, teaching status of hospital, and joint commission certification as stroke center, Estimated odds ratios were obtained for each factor in the model, having adjusted for others, and robust standard errors calculated. SAS Version 9.1.3 (Cary, N.C.) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Response Rate and Demographics

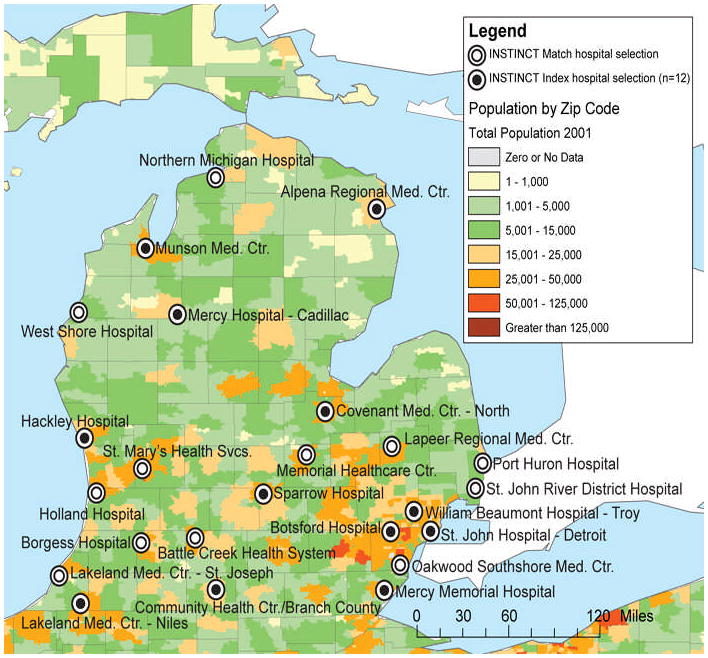

Of the 278 eligible emergency physicians, 199 returned completed surveys, for an overall gross response rate of 71.6%. The response rate by hospital ranged from 30% to 100% [mean 73.3%; median 73.6%]. Characteristics of the hospitals (locations and surrounding population density given in Figure 1) and emergency physicians are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Survey participants reported working an average of 138 clinical hours in the month preceding the survey (median 135 hours) and 81% indicated they had participated (either independently or jointly with specialist consultation) in treating a stroke patient with tPA in the preceding five years.

Figure 1.

INSTINCT Hospitals and Surrounding Population Density

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Hospitals (2007; n = 24)

| Characteristic | n | (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Beds | ||

| < 100 | 4 | (17) |

| 101 – 250 | 12 | (50) |

| 251 – 500 | 5 | (21) |

| > 500 | 3 | (13) |

| Annual ED Volume (adult) | ||

| < 20,000 | 7 | (29) |

| 20,001 – 40,000 | 8 | (33) |

| 40,001 – 60,000 | 7 | (29) |

| 60,001 – 80,000 | 2 | (8) |

| > 80,000 | 0 | (0) |

| Joint Commission Certified Stroke Center | 7 | (29) |

| Teaching hospital | 9 | (38) |

| Neurologist on-staff | 22 | (92) |

| CT availability 24/7 | 24 | (100) |

| Telestroke availability | 4 | (17) |

| Intra-arterial thrombolysis for stroke | 4 | (17) |

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Table 2.

Characteristics of Emergency Physicians

| Characteristic | Survey Response | |

|---|---|---|

| no./total no. | (%)* | |

| Female | 46/199 | (23) |

| Age (years) | Median | 42 |

| Minimum | 28 | |

| Maximum | 65 | |

| Race or ethnic group | ||

| White | 171/192 | (89) |

| Non-white | 21/192 | (11) |

| Black | 6/192 | (3) |

| Asian | 5/192 | (3) |

| Hispanic | 4/192 | (2) |

| Other | 5/192 | (3) |

| Education | ||

| EM residency training | 160/199 | (80) |

| Specialty board certification† | ||

| Emergency medicine | 170/199 | (85) |

| Internal medicine | 8/199 | (4) |

| Family practice | 8/199 | (4) |

| Pediatrics | 1/199 | (1) |

| None | 12/199 | (6) |

| Other | 11/199 | (6) |

| Year of medical school graduation | ||

| 1997 – 2006 | 62/198 | (31) |

| 1987 – 1996 | 72/198 | (36) |

| 1977 – 1986 | 51/198 | (26) |

| 1957 – 1976 | 13/198 | (7) |

| Year of EM residency completion | ||

| 1977 – 1986 | 15/160 | (9) |

| 1987 – 1996 | 58/160 | (36) |

| 1997 – 2006 | 87/160 | (54) |

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Multiple board certifications allowed

Attitudes and Beliefs toward tPA

Specific survey items with their response options and percentage of respondents are located in Table 3. Almost all respondents, 99% [95% CI: 97.8 to 100] indicated the use of tPA in eligible patients with symptoms of acute stroke represented either acceptable or ideal patient care. Evaluated by response option, 57% identified the use of tPA as “ideal,” 42% as “acceptable” and 1% as “unacceptable” patient care. Twenty-seven percent [95% CI: 21.7 to 32.3] indicated the use of tPA represented a legal standard of care in eligible patients with symptoms of acute stroke.

Table 3.

Overall Physician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Use of Intravenous tPA

| Survey Item and Response Options | Ideal patient care AND Legal standard of care | Ideal patient care, NOT Legal standard of care | Acceptable patient care, NOT Legal standard of care | Unacceptable patient care, NOT Legal standard of care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of respondents | ||||

| The use of tPA in eligible patients with symptoms of acute stroke represents: | 27 | 30 | 42 | 1 |

| Survey Item and Response Options | Very Likely | Likely | Uncertain | Unlikely | Very Unlikely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of respondents | |||||

| Assume the ideal setting for tPA use in stroke exists at your local hospital. How likely is it that you would use tPA to treat acute ischemic stroke? | 44 | 39 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| Extremely Comfortable | Comfortable | Neutral | Un-comfortable | Extremely Uncomfortable | |

| How comfortable would you feel giving tPA to a patient WITHOUT a consultation from a neurologist or stroke specialist | 7 | 15 | 13 | 43 | 22 |

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Existing science on tPA use in stroke is convincing | 10 | 39 | 30 | 18 | 3 |

| A telephone consult is sufficient prior to treatment | 22 | 45 | 21 | 9 | 4 |

| Liability for USING tPA is a major concern | 13 | 50 | 21 | 14 | 2 |

| Liability for NOT USING tPA is a major concern | 14 | 45 | 27 | 11 | 3 |

As Table 3 shows, 83% [95% CI: 78.5 to 87.5] of respondents indicated they were “likely” or “very likely” to use tPA given an ideal setting. When asked about using tPA without a consultation, 65% [95% CI: 59.3 to 70.7], indicated they were uncomfortable. A similar majority, 67% [95% CI: 61.4 to 72.7], indicated a telephone consultation would be sufficient prior to treatment.

Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated the science regarding the use of tPA in stroke is convincing [95% CI: 43.0 to 55.0], with 30% remaining neutral. Majorities also agreed that liability for use (or non-use) of tPA is a major concern.

The proportion of emergency physicians responding favorably for various respondent characteristics and practice environments are given in Table 4. Practicing emergency physicians who were not board certified in emergency medicine were more likely to use tPA in an ideal setting, agree that the science on tPA use in stroke is convincing and believe tPA use in eligible patients is a legal standard of care, compared to their board certified counterparts.

Table 4.

Physician Attitudes According to Provider and Hospital Characteristics

| Variable | Likely to use tPA in ideal setting | Agree that existing science on tPA use in stroke is convincing | Agree use of tPA in eligible patients with stroke symptoms is legal standard of care | Comfortable giving tPA without a consultation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board Certification | n | % (OR) (95% C.I.) | % (OR) (95% C.I.) | % (OR) (95% C.I.) | % (OR) (95% C.I.) |

| Emergency Medicine (referent) | 159 | 81 | 46 | 25 | 23 |

| Non-Emergency Medicine | 26 | 96 (5.81) (1.00 – 33.91) | 69(2.65) (1.20–5.87) | 46(2.62) (1.01 – 6.78) | 19 (0.79) (0.28–2.16) |

|

Completion of EM Residency | |||||

| No (referent) | 36 | 89 | 58 | 31 | 25 |

| Yes | 149 | 82 (0.56) (0.18–1.82) | 47 (0.63) (0.40–1.00) | 27 (0.84) (0.45–1.58) | 22(0.85) (0.37 – 1.98) |

|

Year of Medical School Graduation** | |||||

| 1997 – 2006 (referent) | 56 | 82 | 46 | 21 | 20 |

| 1987 – 1996 | 70 | 84 (1.17) (0.45–3.05) | 46 (0.97) (0.47 – 1.99) | 29 (1.47) (0.65–3.31) | 24 (1.31) (0.51–3.37) |

| 1977 – 1986 | 47 | 81(0.92) (0.33 –2.52) | 51 (1.20) (0.50–2.88) | 30(1.60) (0.56–4.57) | 23 (1.25) (0.38 – 4.16) |

| 1957 – 1976 | 12 | 92(2.39) (0.32 – 17.89) | 75 (3.46) (1.13–10.58) | 42 (2.62) (0.79–8.71) | 25(1.36) (0.31–6.01) |

|

Annual ED Volume (adult) | |||||

| < 20,000 (referent) | 33 | 85 | 58 | 28 | 15 |

| 20,001 – 40,000 | 54 | 94(3.04) (0.60 – 15.29) | 48 (0.68) (0.33–1.40) | 30 (1.08) (0.45 – 2.57) | 30(2.36) (0.54 – 10.31) |

| 40,001 – 60,000 | 78 | 81(0.75) (0.30 – 1.89) | 41 (0.51) (0.24–1.07) | 21 (0.66) (0.23 – 1.86) | 26(1.93) (0.51–7.24) |

| 60,001 – 80,000 | 20 | 60 (0.27) (0.09 – 0.81) | 70 (1.72) (0.62 – 4.76) | 50 (2.56) (1.15–5.67) | 5 (0.29) (0.06 – 1.35) |

|

Teaching Hospital | |||||

| No (referent) | 84 | 87 | 49 | 24 | 24 |

| Yes | 101 | 80 (0.61) (0.22–1.68) | 50(1.03) (0.57–1.86) | 31(1.40) (0.70–2.79) | 22(0.89) (0.39–2.04) |

|

Joint Commission Certified Stroke Center | |||||

| No (referent) | 130 | 82 | 51 | 25 | 23 |

| Yes | 55 | 87 (1.55) (0.53–4.54) | 45(0.81) (0.44–1.50) | 33 (1.47) (0.82–2.62) | 22 (0.93) (0.37–2.35) |

|

Gender | |||||

| Female (referent) | 42 | 71 | 50 | 33 | 14 |

| Male | 143 | 87 (2.61) (1.11 – 6.14) | 49 (0.96) (0.51–1.79) | 26 (0.70) (0.43–1.15) | 25 (2.02) (0.58 – 7.04) |

|

Prior Participation in tPA treatment | |||||

| No (referent) | 32 | 75 | 38 | 16 | 0 |

| Yes | 149 | 85 (1.92) (0.87 – 4.26) | 52 (1.83) (0.84–3.98) | 30 (2.36) (0.98–5.68) | 28(N/A) |

Odds ratios adjusted for intra-class correlation of respondents within hospitals. Bolding indicates significance at the 0.05 level.

A trend toward increased odds of a favorable response in the above categories was also observed among older physicians, specifically those who graduated medical school between 1957 and 1976. Male respondents were more likely to use tPA in an ideal setting compared to females.

Emergency physicians practicing at high volume centers (annual ED census between 60,001 and 80,000) were less likely to use tPA in an ideal setting compared to respondents from lower volume emergency departments. A trend toward viewing tPA evidence favorably and identifying tPA use as a legal standard of care was also identified in the group from lower volume emergency departments. In physicians with prior experience using tPA for stroke, a trend toward increased odds of a favorable response was found, but this did not reach significance.

Multiple regression analyses for each of the four outcomes are presented in the web appendix and the results differ from those seen in the univariate analyses in Table 4. In the multivariate analysis of variable 1 (likely to use tPA in an ideal setting) and variable 2 (science on tPA is convincing), it was found that the apparent effect of teaching hospital becomes substantially larger (5.70 versus 0.61 in the first case and 2.08 versus 1.03 in the second). In both cases, the reason for the change is that teaching hospital is highly correlated with ED volume, with larger hospitals more likely to have an educational role.

The adjusted analysis for variable 3 (legal standard of care) is notable in that many variables were highly related to the outcome. The correlation between teaching status and ED volume again plays a role in making both variables more significant. In addition, there is a high correlation between year of medical school graduation and board certification in that physicians with the longest time since medical school tended more frequently to hold emergency medicine board certification. This resulted in both variables becoming more significant when fitted simultaneously in the model. In both the adjusted and unadjusted models, however, there was a clear tendency for those without emergency medicine board certification to view tPA as a legal standard of care. There were no notable differences between the adjusted and unadjusted analyses for variable 4 (comfortable giving tPA without a consultation).

Discussion

In this survey of emergency physicians from a cross section of Michigan community hospitals, we observed greater acceptance of thrombolysis for stroke than previously reported. Nearly all respondents characterized tPA treatment as either ideal or acceptable patient care and approximately one-quarter indicated tPA use represented a legal standard of care in eligible stroke patients. Eighty-three percent indicated they would use tPA given the ideal setting at their local hospital.

Past surveys, from 2003 and 2005, provided acceptance estimates ranging from 53% to 60%.10, 12 Possible explanations for the findings of increased acceptability of tPA use include secular changes in attitudes toward stroke treatment, differences in the survey cohort compared to prior studies and differences in survey design.

A secular trend in physician attitudes toward tPA use in Michigan is plausible given the breadth of stroke activities statewide. The state has multiple hospitals with stroke research programs and an active Department of Community Health that has supported stroke education since 1997. In 2001–02, sixteen Michigan hospitals participated in the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry13, 14 and in 2003 hospitals in the state began participating in the Get With The Guideline – Stroke (GWTG-S) program. Schwamm et al. previously found GWTG-S improved stroke management performance.15

Other potential contributors to a secular trend include competitive efforts by hospitals to achieve primary stroke center designation (Michigan currently has 33 PSCs) as well as the publication of several studies which were concordant with randomized trials on the efficacy and safety of tPA.16–19

Study cohort differences may also explain our findings of increased acceptability of tPA use. We note a higher number of primary stroke centers in our sample than anticipated from nationwide estimates. The reason is unclear, but increased overall presence; random chance; or unknown associations between stroke center status and size or geographic isolation of the included hospitals are all possible.

Previous studies evaluating acceptance of thrombolytics in stroke sampled the membership of the American College of Emergency Physicians.10, 12 While this is the largest of the five emergency medicine (EM) professional organizations, it is not known what proportion of practicing physicians are members. Additionally, response rates in these earlier studies (21 to 43 percent) were substantially smaller than our cohort, increasing the potential for bias. Finally, data indicate 38% of emergency physicians are neither EM residency trained nor EM board certified and these clinicians are more likely to practice in suburban or rural locations.20 Their professional membership is unknown, but it is possible our survey methodology encompassed this population to a greater extent.

Differences in survey design may also explain the increased thrombolytic acceptability in our cohort. While our question assessing use of tPA “in the ideal setting” was identical to that of Brown et al., our survey assessed emergency physician attitudes and beliefs across a number of questions and content domains in order to allow internal comparisons. In general, these were concordant in their findings; however, it is possible this conditioned the respondent to favor one answer modality over another.

Other findings regarding the attitudes and beliefs of emergency physicians are worthy of note. The percentage identifying thrombolytic use as a medical-legal standard-of-care was higher than expected and suggests that cumulative educational efforts and data may be changing perceptions. The gap between the medical-legal response and the overall acceptance of tPA may, in part, represent a perception of lack of access to needed acute stroke resources. This is supported by the finding that 83% were likely to use thrombolytics in an ideal situation.

In univariate analysis there was apparently greater acceptance of stroke thrombolysis by older, as well as, non-EM residency trained physicians. Not surprisingly, prior experience with stroke thrombolysis trended toward an association with positive attitudes toward tPA use. Interestingly, emergency physicians practicing at larger hospitals appeared less comfortable treating stroke with tPA without a consultant than their colleagues at moderate sized hospitals. Several potential explanations for this exist. Physicians at larger facilities may have: less isolated responsibility for acute stroke care; increased access to emergent neurological consultation resources; greater physician and staff turnover (both in ED and consulting staffs); reduced personal contact with specialists and/or increased reliance on physician extenders.

Limitations

In addition to limitations inherent in all survey research, some specific limitations should be noted. Our respondent population was determined by a two-stage, cluster, sampling where the hospital was selected first, recruited, and then the emergency physicians within each recruited hospital surveyed. It is possible the five hospitals which declined to participate (and their accompanying physicians) differed in their prioritization of stroke care compared to participating hospitals.

Our sample included a high number of teaching hospitals; this most likely represents the definition used. A hospital with residents (of any specialty) was defined as a teaching hospital. Additionally, hospitals with a very small annual census of stroke patients were excluded from the study. Thus, the attitudes and beliefs of physicians practicing in such environments are not represented here. Furthermore, given the historical development of stroke care in Michigan caution is warranted in generalizing the results.

Summary

In conclusion, nearly all practicing Michigan emergency physicians responding to this survey indicated that tPA use in eligible patients was ideal or acceptable patient care. Large numbers (83%) reported they would likely use tPA assuming the ideal setting for its use existed at their hospital. This represents a shift in attitudes from prior reports. Characteristics associated with favorable attitudes included: non-emergency medicine board certification; older age and a smaller hospital practice environment.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: Award RO1 NS050372 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the study.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, other than with respect to the review of the grant application at the initiation of the project.

Appendix

Description of Survey Development

Individuals with expertise in survey design and administration, biostatistics, emergency medicine and stroke (Mary Haan, DrPH, MPH; John D. Kalbfleisch, Ph.D., Phillip A. Scott, MD, Shirley M. Frederiksen, MS, RN and Lewis Morgenstern, MD) met multiple times to draft the survey. This initial draft was then pre-tested on approximately 15 attending emergency physicians and emergency medicine residents at the University of Michigan to evaluate acceptability, validity, question design and delivery mechanisms.

The design group then analyzed the pre-test results and modified the survey. The next iteration was pilot-tested by sending it to the attending emergency physicians at three non-university based hospitals, but not participating in the INSTINCT study. These emergency physician groups ranged from 7 to 27 members in size, similar to the size groups found in the INSTINCT cohort. These groups represented 44 total emergency physicians and 28 agreed to participate (response rate 64%).

Information was obtained on respondent demographics, practice environment, prior tPA experience, tPA use knowledge and attitudes and beliefs. In addition to the survey itself, information was collected on the ability to complete the survey online, the time required for completion, where the survey was completed (work, home, etc.) and the type of interruptions, if any, encountered.

Following completion, open-ended questions were asked of the pilot-survey respondents to identify areas of concern, question-specific problems or administration issues. 92% of the test group made comments to improve the survey. The results and comments were then reviewed by the design group and incorporated into the final survey design.

Multivariate Analysis

Below are the results obtained from regression models relating the four outcomes to physician and hospital level variables. GEE methods are used to adjust confidence intervals and p-val90 used for intra-cluster correlation.

V1: “Likely to use tPA in ideal setting”

| Analysis Of GEE Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Standard Error Estimates | |||||

| Parameter | Comparison | odds ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | Pr > |Z| | |

| Intercept | 0.31 | 0.01 | 8.26 | 0.49 | |

| Board Certification | Non EM vs. EM | 7.07 | 1.03 | 48.34 | 0.05 |

| EM residency | Yes vs. No | 1.81 | 0.24 | 13.81 | 0.57 |

| Gender | male vs. female | 2.14 | 0.82 | 5.62 | 0.12 |

| Race | non white vs. white | 1.08 | 0.30 | 3.88 | 0.91 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1987–1996 vs. 1997–2006 | 1.57 | 0.51 | 4.88 | 0.44 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1977–1986 vs. 1997–2006 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 2.66 | 0.56 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1957–1976 vs. 1997–2006 | 2.64 | 0.16 | 42.53 | 0.49 |

| ED volume | 20001–40000 vs. <20000 | 5.12 | 0.83 | 31.68 | 0.08 |

| ED volume | 40001–60000 vs. <20000 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 1.09 | 0.07 |

| ED volume | 60001–80000 vs. < 20000 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.35 | <0.01 |

| Hospital teaching status | Yes vs. No | 5.70 | 1.85 | 17.60 | <0.01 |

| Joint Commission certified PSC | Yes vs. No | 1.90 | 0.53 | 6.81 | 0.33 |

| Prior use of tPA | Yes vs. No | 2.66 | 0.62 | 11.41 | 0.19 |

V2: “Agree that existing science on tPA use in stroke is convincing”

| Analysis Of GEE Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Standard Error Estimates | |||||

| Parameter | Comparison | odds ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | Pr > |Z| | |

| Intercept | 0.18 | 0.02 | 1.33 | 0.09 | |

| Board Certification | Non EM vs. EM | 5.09 | 1.52 | 17.12 | 0.01 |

| EM residency | Yes vs. No | 2.91 | 0.84 | 10.03 | 0.09 |

| Gender | male vs. female | 0.92 | 0.43 | 1.96 | 0.83 |

| Race | non white vs. white | 0.62 | 0.20 | 1.89 | 0.40 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1987–1996 vs 1997–2006 | 0.99 | 0.50 | 1.93 | 0.97 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1977–1986 vs. 1997–2006 | 1.77 | 0.62 | 5.08 | 0.29 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1957–1976 vs. 1997–2006 | 11.55 | 2.01 | 66.42 | 0.01 |

| ED volume | 20001–40000 vs. <20000 | 1.11 | 0.38 | 3.26 | 0.84 |

| ED volume | 40001–60000 vs. <20000 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 1.30 | 0.16 |

| ED volume | 60001–80000 vs. <20000 | 1.88 | 0.54 | 6.56 | 0.32 |

| Hospital teaching status | Yes vs. No | 2.08 | 0.99 | 4.36 | 0.05 |

| Joint Commission certified PSC | Yes vs. No | 0.61 | 0.33 | 1.13 | 0.12 |

| Prior use of tPA | Yes vs. No | 2.38 | 0.90 | 6.30 | 0.08 |

V3: “Agree use of tPA in eligible patients with stroke symptoms is legal standard of care”

| Analysis Of GEE Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Standard Error Estimates | |||||

| Parameter | Comparison | odds ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | Pr > |Z| | |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | <.01 | |

| Board Certification | Non EM vs. EM | 16.06 | 5.14 | 50.21 | <.01 |

| EM residency | Yes vs. No | 4.21 | 1.38 | 12.81 | 0.01 |

| Gender | male vs. female | 0.73 | 0.31 | 1.72 | 0.47 |

| Race | non white vs. white | 0.99 | 0.30 | 3.24 | 0.99 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1987–1996 vs. 1997–2006 | 1.86 | 0.66 | 5.30 | 0.24 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1977–1986 vs. 1997–2006 | 2.63 | 0.56 | 12.27 | 0.22 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1957–1976 vs. 1997–2006 | 17.76 | 2.78 | 113.57 | 0.00 |

| ED volume | 20001–40000 vs. <20000 | 4.86 | 1.14 | 20.73 | 0.03 |

| EDvolume | 40001–60000 vs. < 20000 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 2.09 | 0.32 |

| ED volume | 60001–80000 vs. <20000 | 1.89 | 0.48 | 7.52 | 0.37 |

| Hospital teaching status | Yes vs. No | 6.01 | 1.03 | 34.98 | 0.05 |

| Joint Commission certified PSC | Yes vs. No | 1.58 | 0.82 | 3.05 | 0.17 |

| Prior use of tPA | Yes vs. No | 2.83 | 1.10 | 7.26 | 0.03 |

V4: “Comfortable giving tPA without a consultation”

| Analysis Of GEE Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Standard Error Estimates | |||||

| Parameter | Comparison | odds ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | Pr > |Z| | |

| Intercept | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.60 | 0.02 | |

| Board Certification | Non EM vs. EM | 0.90 | 0.26 | 3.14 | 0.86 |

| EM residency | Yes vs. No | 0.74 | 0.22 | 2.51 | 0.63 |

| Gender | male vs. female | 1.64 | 0.53 | 5.11 | 0.40 |

| Race | non white vs. white | 2.60 | 0.61 | 11.10 | 0.20 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1987–1996 vs. 1997–2006 | 1.31 | 0.58 | 2.96 | 0.52 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1977–1986 vs. 1997–2006 | 0.88 | 0.26 | 2.96 | 0.83 |

| Year medicalschool graduation | 1957–1976 vs. 1997–2006 | 0.83 | 0.13 | 5.15 | 0.84 |

| ED volume | 20001–40000 vs. <20000 | 2.08 | 0.40 | 10.87 | 0.39 |

| ED volume | 40001–60000 vs. < 20000 | 1.32 | 0.35 | 5.00 | 0.69 |

| ED volume | 60001–80000 vs. < 20000 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1.24 | 0.09 |

| Hospital teaching status | Yes vs. No | 1.40 | 0.52 | 3.76 | 0.51 |

| Joint Commission certified PSC | Yes vs. No | 0.98 | 0.37 | 2.60 | 0.97 |

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the US Government.

Conflicsts of Interest/Disclosure

Disclosures: Dr. Scott receives research support from NIH grants R01 NS50373, U01 NS056975, Michigan Blue Cross Blue Shield and the Michigan Department of Community Health #N006648; he previously received support from NIH grant P50 NS442283; provided expert review and testimony in medical malpractice cases and received honoraria from the American Stroke Association, American College of Emergency Physicians (Utah Chapter), University of Utah, Mid-Michigan Regional Medical Center, and the Michigan Neurological Association for speaking on stroke. Ms. Xu reports no disclosures.

Dr. Meurer reports no disclosures.

Ms. Frederiksen reports no disclosures.

Dr. Haan reports no disclosures.

Dr. Westfall reports no disclosures

Dr. Kothari reports no disclosures

Dr. Morgenstern reports no disclosures

Dr. Kalbfleisch reports no disclosures.

Contributor Information

Phillip A. Scott, Email: phlsctt@med.umich.edu.

Zhenzhen Xu, Email: zzxu@umich.edu.

William J. Meurer, Email: wmeurer@med.umich.edu.

Shirley M. Frederiksen, Email: sfred@med.umich.edu.

Mary N. Haan, Email: Mary.Haan@ucsf.edu.

Michael W. Westfall, Email: mwwestfall@comcast.net.

Sandip U. Kothari, Email: skothari@me.com.

Lewis B. Morgenstern, Email: lmorgens@med.umich.edu.

John D. Kalbfleisch, Email: jdkalbfl@umich.edu.

References

- 1.Morgenstern LB, Staub L, Chan W, Wein TH, Bartholomew LK, King M, Felberg RA, Burgin WS, Groff J, Hickenbottom SL, Saldin K, Demchuk AM, Kalra A, Dhingra A, Grotta JC. Improving delivery of acute stroke therapy: The tll temple foundation stroke project. Stroke. 2002;33:160–166. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu DKD, Villar-Cordova C, Kasner SE, Morgenstern LBBP, Yatsu FM, Grotta JC. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: Feasibility, safety, and efficacy in the first year of clinical practice. Stroke. 1998;29:18–22. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katzan IL, Furlan AJ, Lloyd LE, Frank JI, Harper DL, Hinchey JA, Hammel JP, Qu A, Sila CA. Use of tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: The cleveland area experience. Jama. 2000;283:1151–1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman KM, Woolfenden AR, Graeb D, Johnston DC, Beckman J, Schulzer M, Teal PA. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: A canadian hospital’s experience. Stroke. 2000;31:2920–2924. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed SD, Cramer SC, Blough DK, Meyer K, Jarvik JG, Wang DZ. Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator and inpatient mortality rates for patients with ischemic stroke treated in community hospitals. Stroke. 2001;32:1832–1840. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickenbottom S. Preliminary results from four state pilot prototypes of the paul coverdell national acute stroke registry. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grotta JC, Burgin WS, El-Mitwalli A, Long M, Campbell M, Morgenstern LB, Malkoff M, Alexandrov AV. Intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy for ischemic stroke: Houston experience 1996 to 2000. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:2009–2013. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Schneider A, Woo D, Khoury J, Miller R, Alwell K, Gebel J, Szaflarski J, Pancioli A, Jauch E, Moomaw C, Shukla R, Broderick JP. Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke: A population-based study. Stroke. 2004;35:e27–29. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109767.11426.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Improving the chain of recovery for acute stroke in your community. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown DL, Barsan WG, Lisabeth LD, Gallery ME, Morgenstern LB. Survey of emergency physicians about recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Annals of emergency medicine. 2005;46:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidwell CS, Shephard T, Tonn S, Lawyer B, Murdock M, Koroshetz W, Alberts M, Hademenos GJ, Saver JL. Establishment of primary stroke centers: A survey of physician attitudes and hospital resources. Neurology. 2003;60:1452–1456. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063314.67393.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves MJ, Arora S, Broderick JP, Frankel M, Heinrich JP, Hickenbottom S, Karp H, LaBresh KA, Malarcher A, Mensah G, Moomaw CJ, Schwamm L, Weiss P. Acute stroke care in the us: Results from 4 pilot prototypes of the paul coverdell national acute stroke registry. Stroke. 2005;36:1232–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165902.18021.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng YZ, Reeves MJ, Jacobs BS, Birbeck GL, Kothari RU, Hickenbottom SL, Mullard AJ, Wehner S, Maddox K, Majid A. Iv tissue plasminogen activator use in acute stroke: Experience from a statewide registry. Neurology. 2006;66:306–312. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000196478.77152.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Frankel MR, Smith EE, Ellrodt G, Cannon CP, Liang L, Peterson E, Labresh KA. Get with the guidelines-stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2009;119:107–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albers GW, Bates VE, Clark WM, Bell R, Verro P, Hamilton SA. Intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for treatment of acute stroke: The standard treatment with alteplase to reverse stroke (stars) study [see comments] Jama. 2000;283:1145–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill MD, Buchan AM. Thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: Results of the canadian alteplase for stroke effectiveness study. CMAJ. 2005;172:1307–1312. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, Hennerici MG, Kaste M, Kuelkens S, Larrue V, Lees KR, Roine RO, Soinne L, Toni D, Vanhooren G. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the safe implementation of thrombolysis in stroke-monitoring study (sits-most): An observational study. Lancet. 2007;369:275–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von Kummer R, Wahlgren N, Toni D. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moorhead JC, Gallery ME, Hirshkorn C, Barnaby DP, Barsan WG, Conrad LC, Dalsey WC, Fried M, Herman SH, Hogan P, Mannle TE, Packard DC, Perina DG, Pollack CV, Jr, Rapp MT, Rorrie CC, Jr, Schafermeyer RW. A study of the workforce in emergency medicine: 1999. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:3–15. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.124754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]