Abstract

Objective

To examine whether a supportive nursing intervention that promoted kangaroo holding of healthy preterm infants by their mothers during the early weeks of the infant’s life facilitated co-regulation between mother and infant at six months of age.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Participants

Sixty-five mother-infant dyads with mean gestational age at birth of 33 weeks. Fifty percent of infants were male, and 50% were non-White.

Interventions

An eight week home intervention encouraged daily one hour, uninterrupted holding with either blanket (baby wrapped in blanket and held in mother’s arms) or the kangaroo (baby in skin-to-skin contact on mother’s chest) method. In both conditions, weekly home visits by an experienced RN included encouragement to hold the infant, emotional support, and information about infant behavior and development. A control group received brief social visits, had no holding constraints, and participated in all assessments.

Main Outcome Measures

When infants were six months of age, the Still-Face Procedure was used to assess mother-infant interaction. Outcome measures were co-regulation of the dyad’s responses during the play episodes of the Still Face Procedure and vitality in infant efforts to re-engage the mother during the neutral face portion of the Still Face procedure.

Results

Significant differences among groups were found in mother-infant co-regulation. Post hoc analysis showed that dyads who were supported in kangaroo holding displayed more co-regulation behavior during play than dyads in the blanket holding group. No differences were found between groups in infant vitality during the neutral face portion of the Still Face Procedure.

Conclusion

Dyads supported in practicing kangaroo holding in the early weeks of life may develop more co-regulated interactional strategies than other dyads.

Keywords: Prematurity, NICU, Still Face, Mother-infant, holding, intervention

Substantial evidence indicates that high quality maternal-infant interaction is associated with infant development of self regulation, cognitive development, social competence in early childhood, positive sense of self, and secure attachment (Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Barrig Jo, 2008; Jahromi & Stifter, 2007; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006; Moore & Calkins, 2004). Co-regulation is an important quality of interaction during which the dyad functions as an integrated entity to regulate each other’s behavior (Fogel, 2000). According to this view, the dyad is a functional unit that co-creates and responds to new information that was not available to them prior to the current interaction. Early mother-infant interactive history and maternal sensitivity (mother’s recognition and response to infant contributions to the interaction) are important factors contributing to co-regulated interactions (Fogel, 2000). Interactive history supports each member of the dyad to expect certain behaviors in the other that they can apply to subsequent interactive situations. However, dyads that experience flexible co-regulation adapt to new and unexpected behaviors within the interaction (novelty) and are likely to experience encounters as mutually rewarding (Legerstee, Markova, & Fisher, 2007).

Maternal adaptive and sensitive response to infant negative emotions assist the infant in using regulatory strategies to reduce arousal (Kochanska, 2000) and maintain positive affect (Kainmauskiene et al, 2009). However, mismatching of affective states, when responses and interpretations of the dyad are not always coordinated, is also an important experience (Tronick, 2007). Although matching states usually are associated with positive affect and mismatching states with negative affect, dyads sometimes attempt to repair mismatches so that co-regulated, coordinated interaction can continue (Tronick, 2004). Jaffe et al (2001) reported that more optimal outcomes in the mother-infant relationship were associated with moderate, rather than high or low levels of dyadic coordination during early infancy, suggesting that mismatches are an essential aspect of high quality interaction.

Barriers and Obstacles to Quality Communication

Emotional and physiological regulation by the infant is necessary to perform activities involved in communicating with the mother, such as attending to the mother, arousing to match the mother’s affect and behavior, smiling, vocalizing, interpreting the mother’s cues, and sending clear behavioral signals (Feldman, 2007; Weinberg, Olson, Beeghly, & Tronick, 2006). Prematurity may interfere with the infant’s ability to self-regulate, so preterm infants may require additional maternal support during an interaction (Feldman, 2006; Rose, Feldman, & Jankowski, 2001).

Infant immaturity and dysregulation, however, compromise the mother’s confidence to interact optimally with her infant (Amankwaa, Pickler, & Boonmee, 2007; Cornish et al., 2006; Holditch-Davis, Schwartz, Black, & Scher, 2007). Mother-preterm dyads show less cooperativeness and synchrony, and more maternal controlling interaction than dyads in which the infant was born at term (Feldman, 2006; Forcada-Guex, Pierrehumbert, Borghini, Moessinger, & Muller-Nix, 2006). Feelings such as anxiety, fatigue, anger, guilt, and depression reported by mothers of infants who received neonatal intensive care most likely interfere with maternal sensitivity (Lindberg & Ohrling, 2008; Shaw, et al., 2009; Vanderbilt, Bushley, Young, & Frank, 2009).

Holding for Mother-Preterm Infant Dyads

Holding may be an important early care method to assist preterm infants’ emotional and physiologic regulation (Liu et al., 2007). During holding mothers provide containment and flexion of the infant’s extremities, simulating infant position in utero. The most typical holding among United States mothers is blanket holding in which the mother holds the infant, dressed and typically wrapped in a blanket, horizontally or vertically in her arms. Korja, et al. (2008) reported that a longer duration of maternal holding correlated positively with the infant’s positive affect and better quality mother-infant interaction at six months corrected infant age. Conversely, shorter duration of holding was associated with dyadic disorganization and maternal negative affect.

In kangaroo holding, an approach first promoted in Bogota, Colombia to support preterm infant survival and care, the mother holds the infant in skin-to-skin contact, prone and upright on her chest. The mother encloses the diapered but unclothed infant in her own clothing, simulating the contact of a kangaroo mother whose infant completes the gestational period in close contact with the mother in her enclosed pouch. The positive impact of kangaroo holding on preterm infants includes promotion of physiologic stability, optimal gas exchange, and enhanced sleep organization (Bergman et al., 2004; Feldman, Weller, Sirota, Eidelman, 2003; Fohe, Knopf, & Avenarious, 2000; Ludington-Hoe et al., 2006).

Mothers in the hospital setting have reported that during kangaroo holding they and their infants felt calm, and that the mothers felt needed and connected to their infants (Johnson, 2007; Neu, 1999; Roller, 2005), especially when in a supportive environment (Neu, 2004). In a study of mother-preterm infant dyads who practiced kangaroo holding for at least one hour per day for 14 days, mothers showed more sensitivity and nurturing touch, and infants displayed less negative affect at 3 months of age than dyads who received standard care (Feldman, et al., 2003). When compared to dyads who received standard care, infants who experienced kangaroo holding were more alert and showed less gaze aversion at six months of age. Their mothers showed more positive affect, more touch and adaptation to infant cues, less depression and perceived their infants more positively than dyads who received standard care (Feldman, Eidelman, Sirota, & Weller, 2002).

The aforementioned studies used either a qualitative design in which only kangaroo holding was examined (Johnson, 2007; Neu, 1999; Roller, 2005) or were randomized controlled trials comparing support for kangaroo holding to caring for infants lying in bed (Bergman et al., 2004; Fohe et al., 2000; Ludington-Hoe, et al., 2006). Others have compared kangaroo holding to standard care, but the support and attention that mothers received during holding was not measured or controlled (Feldman, et al., 2003; Feldman, et al., 2002). In order to adequately study the benefits of kangaroo holding, it needs to be compared to blanket holding and the amount of attention and support offered to mothers need to be controlled.

CALLOUT #1

We conducted a study to investigate the benefits of an eight week, nurse supported holding intervention for mothers of pre-term infants on mother-infant co-regulation at week eight and when infants were six months of age. This study did control for attention and support that the mother received. Dyads were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: 1) supported kangaroo holding of infants held at least one hour a day in skin-to-skin contact between their mothers’ breasts and wrapped in their mother’s blouse or gown with a receiving blanket covering their backs. Infants’ heads were covered with a blanket. 2) supported blanket holding of infants dressed and/or wrapped in a blanket, and held in their mothers’ arms at least one hour a day; or 3) control with no specific support of holding style or duration.

This article describes the interactive assessment conducted when infants were six months of age. Assessment of mother-infant dyad interaction typically involves asking the mother to sit across from her infant so that the dyad is facing each other, and to play with her infant for several minutes. While some assessment approaches observe unstructured play situations (e.g., Biringen, 2000), the Still Face Paradigm (Tronick, Als, Adamson, Wise, & Brazelton, 1978) is a frequently used dyadic assessment allowing observation of the infant’s response to potentially supportive and maximally unsupportive maternal behaviors during brief episodes: play, maternal maintenance of a neutral face without interaction, and play. The aim of this component of the study was to examine whether a supportive nursing intervention that promoted kangaroo holding of healthy preterm infants by their mothers during the early weeks of the infant’s life facilitated co-regulation between mother and infant at six months of age. The researchers tested the hypotheses that at six months of age (4 months corrected age): 1) Mother-infant dyads who are supported to practice daily kangaroo holding for 8 weeks will show more co-regulated responses during the play episode of a standard still-face procedure compared to dyads who experience blanket holding support or are in the control group; and (2) Infants who experience kangaroo holding for eight weeks will show greater vitalityin their efforts to re-engage mothers during the neutral-face portion of a standard still-face procedure than dyads who experience blanket holding or are in the control group.

Methods

Design

A randomized controlled trial was conducted to compare the effects of two eight week nurse-supported infant holding interventions and a control condition on co-regulation of interactive responses of mothers and their preterm infants at six months of age.

Sample and Setting

Subjects were recruited from the neonatal intensive care units at five hospitals in the metropolitan area of a mid-sized city in the western United States. Inclusion Criteria: Infant gestational age was 32 through 34 weeks (determination of the infant’s gestational age was made by the attending physician). The infant was first born. Oxygen requirement was less then ½ liter O2 per nasal cannula. The infant had no umbilical lines, intraventricular hemorrhage, physical anomalies, or anticipated major surgery. The mother was fluent in English or Spanish. The mother had no maternal recorded or stated illicit drug use and no diagnosis of serious chronic illness. Because we had no prior data, we determined power analysis using the smallest detectable effect size. Power analysis indicated that 44 subjects in each of 3 groups would yield 80% power for a univariate test of group differences using an effect size of .25 and an alpha of .05 (Cohen, 1988).

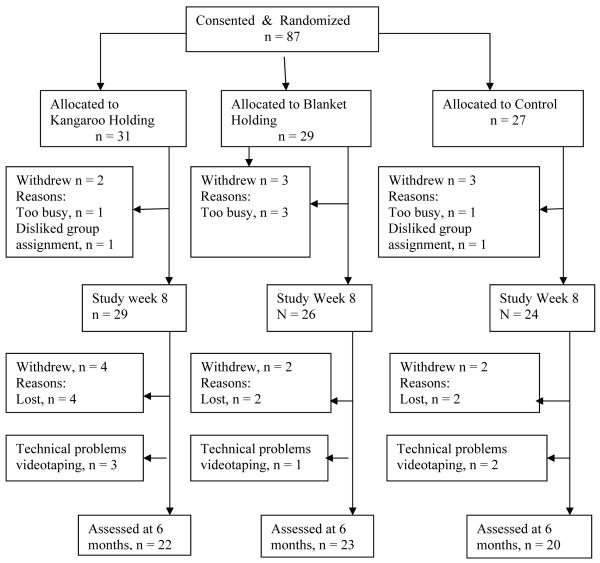

Recruitment was problematic. Approximately 60% (n = 130) of mothers who were approached, declined to be in the study, stating that they felt they would be too busy with the new baby or that they did not want to be assigned to a holding group, an essential feature to rigorously test behavioral interventions. Dyads were recruited within one month after birth of the infant with 58% recruited within 14 days of birth. Of the 87 mothers who consented, 8 (9.2%) withdrew by week 8, and 16 (18.4%) withdrew in total by six months (Figure 1). Technical difficulties prevented successful video recording of 6 dyads resulting in a sample size of 65 dyads. Characteristics of dyads who withdrew did not differ from dyads who remained in the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of all Possible and Actual Dyads for the 6-Month Assessment

Holding practices of mothers assessed at six months are provided in Table 1. Holding practices of the Blanket and Control groups were quite similar.

Table 1.

Number of Subjects Who Practiced Kangaroo Holding During the 8 Week Intervention

| 50-55 days |

45-49 days |

40-44 days |

35-39 days |

30-34 days |

25-29 days |

20-24 days |

15-19 days |

10-14 days |

5-9 days |

1-4 days |

0 days |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kangaroo | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Blanket | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 23 |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 20 |

Procedures

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board of the principle investigator (MN) and the review boards of each study site. Mothers signed informed consent after the study was explained to them and before randomization.

The project director coordinated randomization within each hospital using a computer random number generator and opaque sealed envelopes to conceal allocation. The first author (MN) recruited mother-infant dyads within four weeks after birth of the infant. A folded slip of paper inside the envelope stated either Kangaroo holding, Blanket holding, or Choice of holding. Mothers and researcher were blind to allocation until the envelope was opened.

Dyads in the kangaroo and blanket holding groups were visited by an RN in the hospital or at home twice a week for 2 weeks followed by weekly visits for 6 weeks. The visits lasted 45-60 minutes and consisted of providing encouragement in holding, promotion of relaxation during holding, information about early infant development, and education about recognition and response to infant cues. Benefits of only their assigned holding method were discussed with mothers in the two nurse-supported groups. Mothers also were instructed to hold their infant, using the assigned method for 60 consecutive minutes at least once daily. Mothers in the blanket group were asked not to use the kangaroo method, but were not prohibited from doing so. In the control group, however, although blanket and kangaroo holding were explained to mothers during the first visit, neither holding method was encouraged. Visits in the control group lasted 10 to 20 minutes and content of these visits focused on completion of the study forms and general health of the mother and infant.

Visits at home rather than hospital were most common. Thirty percent of dyads received all visits at home; 43% received all but 1-2 visits at home; 24% received all but 3-4 visits at home; and 3% received half of the visits at home. The percent of visits at home were similar among the 2 nurse-supported holding groups as were the percent of visits completed. Eight visits were received by 81.82% and 87% of dyads in the kangaroo and blanket group respectively. Seven visits were received by 18.18% and 13% of dyads respectively. Dyads in the control group received 7 visits (55%) and 6 visits (45%). All mothers were offered a holding diary and were asked to record the daily amount of holding, who held the infant, and the type of holding.

During Week 1, demographic data and questionnaires assessing maternal depression and anxiety were completed by the mothers before the first holding observation. Mothers completed the anxiety and depression questionnaires again before the holding observation in Week 8. The first author and another RN conducted the home visits and collected the questionnaires and holding diaries.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaires

Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire addressing age, ethnicity, education, occupation and health during the 1st visit. Hospital records were used to obtain information about the infant, birth and pregnancy. The Hollingshead Four Factor Index (1975) was used to measure socioeconomic status (SES). In a study of 140 adults, inter-rater agreement was .89 (Cirino et al, 2002). Cirino et al (2002) also reported concurrent validity with other measures of SES (r = .81) with the Socioeconomic Index of Occupations (Nakao and Treas, 1992) and (r = .86) with the Socioeconomic Index for Occupations in Canada (Blishen, Carroll & Moore, 1987).

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a widely used self-report measure to assess maternal depressive symptoms. CES-D scores have been reported to be stable over the first year postpartum. Mothers with elevated scores show less optimal ability to interact with their infants and poorer psychosocial functioning than mothers who score in the normal range (Beeghly, et al., 2002).; Weinberg et al., 2001; Weinberg et al., 2006). Mothers completed the CES-D at weeks 1 and 8 of the study. Depression was a possible covariate to the outcomes of the study.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Speilberger, Gorsuch, Luchene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1989) was used to assess maternal trait and state anxiety. It is a self-report instrument that has been used extensively in research with women similar to those in this study. State anxiety refers to anxiety that is temporary and exists at a certain time and under certain circumstances. Trait anxiety refers to relatively stable anxiety-proneness. Spielberger et al. (1989) reported concurrent validity of both scales with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory at .70. Test-retest stability for the trait scale after 104 days for College age females was .77 and for state anxiety was .31(Spielberger et al., 1989). Anxiety was considered a possible covariate.

Still Face Paradigm

The Still Face Paradigm (Tronick, et al., 1978) has been widely used with infants born at term (Hsu & Sung, 2008; Rosenblum, McDonough, Muzik, Miller, & Sameroff, 2002; Yato et al., 2008) and preterm (Hsu, & Jeng, 2008; Segal et al., 1995) from 2 to 9 months of age to assess mother-infant interaction and infant response to sudden, unexpected change in maternal emotional expressions. The paradigm provides three assessment conditions, each lasting 2 to 3 minutes: (a) a face-to-face maternal-infant social interaction, (b) a neutral-face period in which the mother maintains a neutral face, and (c) a reunion phase of mother-infant face-to-face social interaction (Weinberg & Tronick, 1996). During the neutral-face period, infants typically appear stressed by the mismatching of the mother’s unresponsiveness to the infant’s bid for attention and they typically display more negative affect than during play (Hsu & Sung, 2008; Rosenblum et al., 2002; Yato et al., 2008). During the reunion phase infants have been reported to alternate between negative and positive behavior toward the mother (Moore & Calkins, 2004; Weinberg & Tronick, 1996) as the dyad works to repair mismatches that occurred during the neutral face. Weinberg & Tronick (1996) postulate that this period is demanding for the infant who is juggling positive feelings of resuming contact with the mother and residual negative feelings from the stress of the neutral-face episode. The Still Face paradigm was chosen because of the ability to assess maternal-infant co-regulation which was a primary outcome measure of this study.

The Principal investigator (PI) contacted mothers when infants were between 24 and 26 weeks postnatal age and an appointment was scheduled as close to 26 weeks as possible. Mothers were encouraged to bring their infants to the laboratory for the observation, but a home visit was done if the mother lacked transportation. Infants were seated in an infant seat placed on a table directly across from the mother, who was seated in a chair. In the laboratory, the dyad was in a room with a one-way mirror and a closed door. Two cameras were used in the lab and at home, one focused on the mother and the other focused on the baby. In the laboratory, the camera signals were transmitted through a split-screen generator to produce one image of mother and baby.

The PI was present for all observations and was accompanied by another RN for 95% of the observations to insure that consistent instructions were given to the mother. Mothers were instructed not to touch the infant during the observation and to (a) play with the infant for 2 minutes, (b) maintain a neutral face without talking to the infant for 2 minutes, and (c) play again with the infant. These episodes were separated by 15 second intervals when the mother looked to the side (Tronick et al, 1978). Mothers were signaled to begin playing with the infant or to change behavior by a knock on the door. In the home, the examiner stayed out of site of the dyad during the observation, and knocked on the door (or wall).

Fogel Scoring System for Still Face Observation

In order to measure mother-infant co-regulation during interaction, the scoring suggested by Fogel (1994) was used for the pre neutral-face play and the post neutral face reunion periods of the Still Face observation. This scoring system considers the dyad as a unit with interactive patterns that are continuously and jointly co-created and innovative (Fogel, 2000). Scoring is done second by second. The Fogel system has been used to demonstrate that: (a) infants vocalize more during symmetrical than unilateral interaction (Hsu & Fogel, 2003), (b) characteristics of the dyad shape stability and transition of dyadic communication patterns in early infancy (Hsu & Fogel, 2003), (c) symmetrical co-regulation is positively associated with infant development (Evans & Porter, 2009), (d) significant relationship exists between the co-regulation codes and maternal efficacy, infant temperament, and physiological measures of regulation (Porter, 2003), and (e) maternal touch influences mother-infant co-regulation during mother-infant face-to-face interaction (Moreno, Posada & Goldyn, 2006). Scoring categories are:

Symmetrical Co-regulation: The dyad shares a joint focus of attention. Each member adds to the interaction. For instance, infant smiling, laughter, reaching to the mother, or crying changes the interaction. An example of symmetrical co-regulation is a peek a boo game (Hsu & Fogel,2003).

Asymmetrical Co-regulation: The dyad shares a joint focus of attention, but only one member of the dyad provides innovation, while the other member (typically the infant) watches.

Unilateral Regulation: The dyad does not share a joint focus of attention. One member of the dyad is absorbed in self-activity (typically the infant) while the other member attends to the activity and/or attempts to attract the attention of that member.

Disruptive: One member of the dyad performs an inappropriate intrusive action that disrupts the innovative behavior of the other member. An example is mother looming in on an infant’s face.

Non engaged: Neither member attempts to interact with the other.

A category is coded if the duration lasts at least 2 seconds. Although symmetrical, asymmetrical, and unilateral interaction are all considered co-regulated activities, symmetrical co-regulation is the most co-participatory and innovative, thus most suggestive of co-regulation.

Four coders scored the play observations for co-regulation. One coder had previously established reliability with the first author and the other three were trained by the first author. In mock sessions, coders practiced with 5 to 7 observations, until 90% agreement was reached. When discrepancies occurred during training or reliability checks, the area of disagreement was discussed and a consensus code entered. Two coders who were research assistants on the project were blind to the hypothesis of this portion of the study but not to group assignment of the dyads. Two coders who had no connection to the study and were blind to group assignment and hypotheses were added to decrease chance of bias. Percent agreement was calculated for 20% of randomly chosen observations. Average percent agreement across the co-regulation codes for pre and post neutral face play observations (phases a and c) was .94 and kappa was .88.

Infant Regulatory Scoring System

The secondary outcomes measure was infant vitality during the neutral face period of the Still Face Observation that was measured using the Infant Regulatory Scoring System (IRSS, Weinberg & Tronick, 1996). This scoring system typically is used with young infants born at term (Hsu & Sung, 2008; Yato et al., 2008) and preterm (Hsu, & Jeng, 2008; Segal et al., 1995).

Behaviors of the infant during the maternal neutral face were coded second by second using the Observer 5.0 software (Noldus Information Technology; Leesburg, VA). The codes gaze at mother’s face with happy expression, laughing or cooing vocalizations, one or two hand reach, and lean forward behaviors were aggregated to represent infant vitality in positive bids for mother’s attention, The code negative vocalizations, crying or fussing, represented infant vitality in negative bids for mother’s attention.

For the infant scores during the neutral face episode, two coders who were blind to the hypothesis of the study scored infant behavior. During training, coders scored the first 5 observations until 90% agreement was reached using Observer software . The Observer software calculated inter-rater agreement of 90% on 20% of randomly selected observations.

Data Analysis

The proportion of time spent in symmetrical, asymmetrical, and unilateral interaction was calculated in phases (a) and (c) (pre and post maternal neutral face). The proportion of time the infant spent in positive and negative bids for attention was used to determine infant vitality during phase (b) (neutral face). Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to determine differences in symmetrical, asymmetrical and unilateral interaction in the pre and post neutral face periods, and to determine differences in infant positive and negative bids for attention during the neutral face period. Demographic variables that differed between groups were used as covariates in the analysis.

Results

Randomization succeeded in equating most demographic characteristics of participants remaining in the study. The Kangaroo mothers had higher depression symptom scores (15.7) than the other two groups p = .047. As part of the study design, the Control group had less hours of visiting than the other groups (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Background Characteristics of Sample

| Sample who Completed Eight Weeks of Holding |

Still Face Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kangaroo Holding n = 29 |

Blanket Holding n = 26 |

Control n = 24 |

Kangaroo Holding n = 22 |

Blanket Holding n = 23 |

Control n = 20 |

|

| Maternal Characteristics | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 25.79 (6.84) | 25.88 (7.26) | 26.63 (5.90) | 26.09 (6.91) | 25.65 (7.00) | 25.95 (5.61) |

| Hollingshead Scorea | 38.33 (15.86) | 36.71 (14.44) | 38.58 (14.54) | 37.25 (15.17) | 37.33 (14.26) | 40.35 (12.85) |

| Daily Hours Maternal Holding (not feeding or sleeping)b |

2.56 (1.08) | 2.45 (0.87) | 2.46 (1.59) | 2.57 (1.19) | 2.43 (0.91) | 2.28 (1.40) |

| Daily Holding Hours (Maternal and Others; not feeding or sleeping)b |

4.81 (2.12) | 4.55 (1.31) | 4.79 (1.59) | 4.88 (2.35) | 4.50 (1.33) | 4.88 (2.21) |

| Depression Score Baselinec |

15.41 (6.81) | 11.19 (7.29) | 11.50 (8.97) | 14.91 (5.91) | 11.17 (7.70) | 9.50 (7.69) |

| Anxiety Score Baseline | 68.59 (13.74) | 67.27 (18.65) | 62.92 (15.08) | 65.82 (12.92) | 68.17 (19.52) | 63.10 (16.50) |

| Days Breast Fed | 32.45 (29.83) | 36.85 (33.09) | 38.75 (31.21) | 33.73 (31.65) | 38.57 (32.63) | 39.40 (30.18) |

| Hours of home visiting received by motherd |

6.57 (0.74) | 6.30 (0.97) | 2.14 (1.16) | 6.55 (0.77) | 6.37 (1.01) | 1.95 (0.62) |

| Infant Characteristics | ||||||

| Gestational Age, Birth (wks) |

33.14 (1.09) | 33.42 (0.90) | 33.42 (0.88) | 33.11 (1.07) | 33.41 (0.93) | 33.47 (0.87) |

| Birth Weight (kg) | 1.99 (0.45) | 1.88 (0.34) | 1.98 (0.36) | 2.02 (0.46) | 1.85 (0.34) | 1.98 (0.38) |

| Illness Score, Birth | 3.97 (2.86) | 3.15 (2.69) | 4.79 (3.71) | 4.09 (2.89) | 3.17 (2.82) | 4.35 (2.83) |

| APGAR 1 minute | 7.21 (1.76) | 7.15 (1.69) | 6.46 (1.85) | 7.32 (1.59) | 7.09 (1.73) | 6.85 (1.53) |

| APGAR 5 minutes | 8.69 (0.54) | 8.58 (0.90) | 8.04 (1.55) | 8.73 (0.55) | 8.57 (0.94) | 8.15 (1.60) |

| Days Hospitalized | 21.66 (10.86) | 23.46 (8.25) | 19.08 (6.41) | 21.91 (10.86) | 23.48 (8.41) | 18.45 (5.47) |

| Days on Oxygen | 8.31 (14.64) | 7.12 (17.03) | 11.67 (20.47) | 7.23 (15.67) | 7.96 (17.98) | 13.65 (21.94) |

| Days under Bililights | 3.31 (2.00) | 2.40 (1.68) | 2.79 (1.67) | 3.55 (2.15) | 2.50 (1.77) | 2.80 (1.54) |

| Corrected Age at Observation (months) |

4.92 (0.57) | 4.90 (0.46) | 4.85 (0.31) | |||

The range of the Hollingshead Scale is 8 to 66.

Amount of holding was calculated as the average number of hours of holding per day per amount of days in which holding was recorded on the diaries after infant discharge from the hospital. Mothers were asked to record the amount of holding in the hospital, but days of hospitalization were quite variable and 42% of the sample had one or no hospital days when diary recording was initiated.

p = .047 for Still Face sample

p = .000 for whole sample and Still Face sample.

Table 3.

Other Characteristics of Sample

| Characteristics | Whole Sample | Still Face Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kangaroo Holding n = 29 |

Blanket Holding n = 26 |

Control n = 24 |

Kangaroo Holding n = 22 |

Blanket Holding n = 23 |

Control n = 20 |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Male Gender | 18 (62.07) | 12 (46.15) | 9 (37.50) | 13 (59.09) | 11 (47.82) | 9 (45.00) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, Non Hispanic | 14 (48.28) | 12 (46.15) | 13 (54.16) | 10 (45.45) | 11 (47.83) | 12 (60.00) |

| Hispanic | 7 (24.14) | 6 (23.09) | 4 (16.67) | 6 (27.27) | 5 (21.74) | 3 (15.00) |

| African American | 2 (6.90) | 4 (15.38) | 3 (12.50) | 2 (9.10) | 3 (13.04) | 2 (10.00) |

| Mixed Race | 6 (20.68) | 4 (15.38) | 4 (16.67) | 4 (18.18) | 4 (17.39) | 3 (15.00) |

| Feeding Type | ||||||

| Breast Feeding Only | 3 (10.34) | 2 (7.69) | 1 (4.17) | 3 (13.64) | 2 (8.69) | 1 (5.00) |

| Breast and Bottle | 14 (48.28) | 12 (46.15) | 11 (45.83) | 11 (50.00) | 10 (43.48) | 9 (45.00) |

| Bottle Feeding Only | 12 (41.38) | 12 (46.15) | 12 (50.00) | 8 (36.36) | 11 (47.83) | 10 (50.00) |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 23 (79.31) | 19 (73.08) | 20 (83.33) | 18 (81.81) | 18 (78.26) | 17 (85.00) |

| Location of Still Face | ||||||

| Observation | 9 (40.91) | 10 (43.48) | 9 (45.00) | |||

| Home | 13 (59.09) | 13 (56.52) | 11 (55.00) | |||

| Laboratory | ||||||

Hypothesis #1, Pre/Post Neutral Face Co-Regulation

Because depression is reported to compromise maternal-infant interaction (Weinberg et al, 2006) and baseline depression differed between groups, the analysis was conducted with depression as a covariate. Chi-square analysis did not reveal distribution differences among groups in infant sex. However, proportions appeared uneven (Table 3) and sex has been reported to influence the dyad interaction (Weinberg et al., 2006) so sex also was used as a covariate. MANCOVA analysis showed no group differences in symmetrical, asymmetrical, and unilateral interaction in phase (a) pre neutral face (Pillai’s Trace (F (6,118) = 1.456, p = .199). A difference was found between groups (Pillai’s Trace (F (6,118) = 2.577, p = .022) in phase (c) post neutral face (Table 4). The two variables that contributed to the difference were the proportion of symmetrical and asymmetrical co-regulation. Contrasts showed that dyads in the kangaroo group showed more symmetrical, and less asymmetrical co-regulation than dyads in the blanket group, and a trend toward more symmetrical behavior and less asymmetrical co-regulation than dyads in the control group. Table 4 displays means of co-regulatory interaction using percentages of the 2-minute post neutral face observation time.

Table 4.

Comparison of Group Meansa for Post Still Face Co-regulation by MANCOVA (sex and maternal depression at baseline as covariates)

| Variables | F Statistic |

P value | Means (SE) Kangaroo Blanket Holding Controlb |

95% Confidence level | Comparison | Contrast p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetrical Co-regulation |

3.163 | .049 | 35.73 (4.87) 19.35 (4.61) 22.28 (5.03) |

25.98 10.11 12.22 |

45.47 28.58 32.35 |

Kangaroo vs. Blanket Holding |

.019 |

| Kangaroo vs. Control |

.066 | ||||||

| Asymmetrical Co-regulation |

3.213 | .047 | 32.63 (5.45) 50.94 (5.17) 48.22 (5.64) |

21.72 40.60 36.95 |

43.55 61.28 59.50 |

Kangaroo vs. Kangaroo vs. Blanket Holding |

.019 |

| Kangaroo vs. Control. |

.057 | ||||||

| Unilateral Regulation |

0.148 | .863 | 31.58 (5.89) 29.46 (5.58) 26.87 (6.09) |

19.80 18.30 14.70 |

43.37 40.63 39.05 |

||

Means are the percentage of the observation spent in the activity

Values are reported in order of group, with Kangaroo listed first, Blanket Holding second and Control third.

Although 44 dyads per group were required for data analysis based on initial power analysis targeting effects as small as d = .25, only 20 per group were available for this 6-month analysis. With this sample size, power was still sufficient to detect effects as small as d = .50 with 80% power at alpha = .05. This is still a moderate effect size and effects smaller than d = .50 are unlikely to be theoretically interesting. Therefore, we believe that significance tests were valid even with the smaller than anticipated sample size.

CALLOUT #2 ABOUT HERE

Two codes in the Fogel Scoring System (Fogel, 2000) were not used in the analysis because they occurred too infrequently to analyze: Disruptive behavior was noted for less than 20 seconds in 8 dyads pre neutral face, and in 4 dyads post neutral face. The occurrence of disruptive behavior was similar among groups. Unengaged behavior was not observed.

To assess the quality of infant affect in the kangaroo group during dyad reunion (phase c), the proportion of infant positive behavior (smiling, laughing, reaching for mother) was examined. Infants in the kangaroo group spent 28.5% (± 23.7) of the 2-minute reunion displaying positive behaviors, compared to 9.6% (±10.9) in the blanket group, and 21.8% (± 24.8) in the control group. A nonparametric analysis, Kruskal-Wallis, used because of unequal variances, showed a difference among groups, X2 (2, N = 64) = 7.88, p = .019).

Hypothesis #2, Neutral Face Infant Vitality

During phase (b), neutral face, positive and negative vitality can be evaluated as the infant bids for maternal attention. Positive and negative vitality was compared between groups using MANCOVA with maternal depression and infant sex as covariates. No difference was found (Pillai’s Trace (F (2,62) = 1.13, p = .345) between groups. Table 5 shows the group percentages of positive infant behavior and negative protest during the 2-minute neutral face.

Table 5.

Comparison of Group Meansa for Infant Behavior During Still Face Period by MANCOVA

| Variables | F Statistic |

Significance | Means (SE) Kangaroo Blanket Holding Control b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Protest | 0.558 | .575 | 28.07 (6.90) 33.35 (6.53) 39.25 (7.12) |

| Total Positive Bids for Attention |

0.718 | .492 | 19.17 (3.89) 13.22 (3.68) 15.81 (4.02) |

Means are the percentage of the observation spent in the activity

Values are reported in order of group, with Kangaroo listed first, Blanket Holding second and Control third.

Discussion

Hypothesis 1, that at six months of age (4 months corrected age): mother-infant dyads who experienced daily kangaroo holding for 8 weeks would show more co-regulated responses during play during a standard still-face procedure than dyads who experienced blanket holding or were in the control group, was partially supported by results of this study. Dyads who experienced kangaroo holding an average of one hour per day for 8 weeks did not display differences in co-regulatory interaction before the maternal neutral face but did display more symmetrical, and less asymmetrical interaction in the reunion phase, after stress of the neutral face. Hypothesis two, that infants who experienced kangaroo holding for 8 weeks would show greater vitality in their efforts to re-engage mothers during the still-face portion of a standard still-face procedure than infants who experienced blanket holding or were in the control group, was not supported.

Both symmetrical and asymmetrical interactions are considered co-regulatory, but symmetrical co-regulation is described by Fogel & Garvey (2007) as communication that is mutually engaging. Mother and infant movements flow continuously with neither one as initiator or follower, yielding co-created, novel information that was not available to the dyad before this interaction (Fogel & Garvey, 2007). Mutual unity observed during symmetrical interaction differs from more passive infant contribution in asymmetrical interaction, suggesting a higher level or more optimal co-regulation in symmetrical than asymmetrical interaction. No differences in symmetrical or asymmetrical co-regulation were found among groups in the pre neutral face portion of the observation. Mothers played with their infants, but could not touch them. The findings indicate that in a relatively low stress play activity, neither type of holding nor the intervention used in this study influenced co-regulatory interaction.

Differences among groups in this study were found in the reunion phase or phase (c) post neutral face period. The kangaroo group demonstrated more symmetrical behavior than the other two groups. The blanket holding and the control groups were similar in demographics and holding practices. The only difference was the structured home visiting intervention received by the blanket holding group. Structured home visiting was an intervention for the nurse supported holding groups, but apparently not an effective one. If it had been effective, the blanket group would have been more similar to the kangaroo group, not the control group. However, as Anderson (2003) reported, some intervention is needed to promote kangaroo holding. Findings in this study that mothers in the control group, who were unsupported in their holding choice primarily chose blanket holding support Anderson’s opinion.

The reunion phase of the observation is challenging for the dyad as both members attempt to repair the mismatches that occurred during the neutral face phase, and infants may continue to display residual distressed behaviors (Moore & Calkins, 2004; Weinberg & Tronick, 1996). Either positive or negative interaction may be symmetrical, but it may be easier for the dyad to re-establish symmetry when both members display positive affect. In this study, infants in the kangaroo group displayed more positive behavior than infants in the other two groups after the stress of the neutral face. Their ability to arouse to meet the mother’s positive affect and to contribute to the interaction by actively smiling and vocalizing suggests that they were more self-regulated than the other infants. The enhanced self-regulation may be due to physiologic regulation that was assisted by kangaroo holding and reported by others (Bergman et al., 2004; Fohe, et al., 2000).

Mothers in the kangaroo group had higher levels of depression at the time of study enrollment than the other two groups. Depression has been reported to interfere with quality of mother-infant interaction (Lindberg & Ohrling, 2008; Shaw et al., 2009). Our results suggest that the combined effects of nursing support and kangaroo holding on symmetrical co-regulation overrode the potential negative effects of maternal depression. Feldman et al. (2003) suggested that the close contact experienced by mothers and infants during kangaroo holding improves symmetry in the relationship. Symmetry that forms in the early weeks of life seems to permeate the relationship several months later. This is especially important with high-risk groups such as dyads in which the infant was born preterm (Amankwaa et al., 2007; Cornish et al., 2006; Forcada-Guex et al., 2006; Holditch-Davis et al., 2007) for whom supportive interventions are particularly needed.

Because history/experience in the relationship contributes to the repair of mismatches (Kalinauskiene et al., 2009), results of this study suggest that dyads who were kangaroo holding developed a positive way to repair mismatches. The neutral face is a novel experience for most dyads and mothers and infants in the kangaroo group responded to this novelty with co-regulatory skills that allowed them to have a rewarding experience even after the stress of the neutral face episode.

Findings from two other longitudinal studies addressing mother-infant interaction in dyads who practiced kangaroo holding have been reported (Chiu & Anderson, 2009; Feldman et al., 2002). Feldman et al. (2002) who compared blanket holding under “standard care” conditions to supported kangaroo holding, found that during a low stress play interaction mothers who had practiced kangaroo group were more sensitive than mothers who had practiced blanket holding, but infants behaved similarly in the two groups. The infant sample in the Feldman et al. (2009) study was very similar to the current study sample. In the current study, interactions did not differ among groups during the low stress play episode prior to the neutral face condition, similar to the report by Feldman and colleagues (2002). However, infants and dyads who were supported in kangaroo holding showed more optimal interaction during the higher stress reunion phase. Findings suggest that kangaroo holding may foster resilience in the dyadic relationship to manage stress or novelty with ease.

Chiu and Anderson (2009) in a randomized controlled trial also examined mother-infant dyads when preterm infants were six months of age. Dyads practicing kangaroo holding were compared to dyads receiving “routine” care who practiced blanket holding. Dyads were encouraged and supported to begin kangaroo holding within the first 42 hours after birth and practiced kangaroo holding for at least one hour a day over a 5-day period. In structured feeding and teaching observations during which maternal sensitivity to infant cues, response to distress and social-emotional and cognitive growth fostering were assessed, Chiu and Anderson found comparable maternal scores at six months between the two groups. The infant score components of the observations were clarity of cues and response to mother. Infants who received kangaroo holding, showed significantly lower scores than infants who received blanket holding. These results contrast with those of the current study in which dyads who practiced kangaroo holding were more mutual partners during interaction than dyads practicing blanket holding. In the current study, dyads practiced kangaroo holding for 8 weeks. Differences in findings might be due to the extended kangaroo holding period in the current study.

Unilateral interactions reflect un-coordinated behavior. One member of the dyad is self-occupied and the other is trying to engage that member in a dual interaction. No differences among groups were found in unilateral interaction in this study. Moderate, not high levels of coordinated behavior are associated with the most optimal outcomes in the mother-infant relationship so unilateral interaction is important in the dyadic interface (Jaffe et al., 2001). Interaction stimulates infants so they often use gaze aversion or turning away to stop interacting and regulate themselves (Sumner & Speitz, 1994). Infants in this study spent approximately one-third of the observation in unilateral interaction, which is similar to the amount reported in a study of 3 to 4 month-old infants born at term (Moreno et al., 2006). The infrequency of occurrence of disruptive and unengaged behavior in mother-infant dyads has been found in other studies (Evans & Porter, 2009).

Limitations

Loss of 25% of the sample for this 6-month assessment should be considered when assessing results of this study. In order to adequately compare holding practices of the three groups, mothers were asked to self-report amount and type of holding using diaries that were collected and monitored weekly. This necessitated a brief description of kangaroo holding to the control group. Maintaining a diary focused on holding may have increased the amount of holding done in the control group, but it did not appear to influence their type of holding. Most mothers in the control group chose the blanket method. Direct observation or videotaping holding would be more exact than maternal self-report but not practical for more than brief episodes. Two coders for the Still Face were not blind to the hypotheses of the study which is a potential source of bias, although two additional coders who were blinded to the hypotheses and group assignment were added for the co-regulation coding.

Future research focused on the time of initiation and duration of holding will be helpful in establishing optimal dosage of kangaroo holding. Feldman et al (2002) found superiority in dyadic interaction after at least 2 weeks of daily kangaroo holding between kangaroo dyads and a blanket holding comparison group, but holding was not randomly assigned. Chiu and Anderson did not find differences in infant behavior after 5 days of kangaroo holding suggesting that more time might be needed. Neither study examined holding practices after discharge, so it is unknown what holding practices were at home. Longitudinal research spanning several years may show continued benefits for preterm infants when compared to blanket holding.

Implications

Many mothers may not appreciate being influenced to adopt a particular holding method, as evidenced by the high rate of refusal to participate in this study. Yet, some encouragement seems necessary for mothers who may be interested in the method but need more than information to adopt kangaroo holding. Mothers in the control group in this study had knowledge of the kangaroo method, but without support, most did not try it or used it minimally. When preterm infants are hospitalized, nurses can educate and provide support and encouragement to mothers to hold kangaroo style. Information that the method can also be used at home and suggestions for implementation at home, may prolong the experience for some mothers. The potential of enhanced infant regulation and more rewarding interactional experiences are benefits that nurses can include when discussing kangaroo holding.

CALLOUT 3

Conclusions

Results of this study add support to the literature on kangaroo holding that preterm infants and their mothers who experience kangaroo holding in the early days or weeks of life, display more optimal dyadic interaction than dyads who do not receive kangaroo holding. Findings also suggest that kangaroo holding may override the negative effects of maternal depression on the dyad’s early relationship. There are two important strengths in this study: (1) kangaroo holding was compared to blanket holding, when mothers received carefully monitored and identical amounts of attention and guidance in the early weeks of life, and in regard to holding; and (2) the control group who received brief visits and recorded holding had similar holding times to the groups that received more support to hold. This creates a conservative test of the hypothesis that amount of holding responds to any support by nurses. Findings from carefully controlled research are necessary when encouraging a practice such as kangaroo holding that seems to have long-range benefits for mothers and their preterm infants.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NICHD HD40892-02 5 K23 and MO1-RR00069, General Clinical Research Centers Program, NCRR, NIH.

Author Bios

Madalynn Neu, RN, PhD, is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, CO.

JoAnn Robinson, PhD, is a professor and director, Early Childhood Education and Early Intervention, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT.

Footnotes

- To adequately study the benefits of kangaroo holding, it needs to be compared to blanket holding with the amount of support offered to mothers controlled.

- Dyads in the kangaroo group showed more symmetrical, and less asymmetrical co-regulation than dyads in the Blanket and Control groups.

- This study strengthens existing findings by comparing kangaroo holding to blanket holding. Mothers also received identical amounts of attention and guidance in regard to holding.

References

- Amankwaa LC, Pickler RH, Boonmee J. Maternal responsiveness in mothers of preterm infants. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 2007;7:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GC, Chiu SH, Dombrowski MA, Swinth JY, Albert JM, Wada N. Mother-newborn contact in a randomized trial of kangaroo (skin-to-skin) care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32:604–611. doi: 10.1177/0884217503256616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J, Tronick EZ. Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman NJ, Linley LL, Fawcus SR. Randomized controlled trial of skin-to-skin contact from birth versus conventional incubator for physiological stabilization in 1200-to 2199-gram newborns. Acta Paediatrica. 2004;93:779–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z. Emotional availability: Conceptualization and research findings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:104–114. doi: 10.1037/h0087711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blishen BR, Carroll WK, Moore C. The 1981 socioeconomic index for occupations in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology. 1987;24:465–488. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SH, Anderson GC. Effect of early skin-to-skin contact on mother-preterm infant interaction through 18 months: randomized control trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.005. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish AM, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C. Maternal depression and the experience of parenting in the second postnatal year. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006;24:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cirino PT, Chin CE, Sevcik RA, Wolf M, Lovett M, Morris RD. Measuring socioeconomic status: reliability and preliminary validity for different approaches. Assessment. 2002;9:145–155. doi: 10.1177/10791102009002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, Barrig Jo PS. Predicting aggressive behavior in the third year from infant reactivity and regulation as moderated by maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:37–54. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CA, Porter CL. The emergence of mother-infant co-regulation during the first year: Links to infants’ developmental status and attachment. Infant Behavior and Development. 2009;32:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. From biological rhythms to social rhythms: Physiological precursors of mother-infant synchrony. Developmental Psychiatry. 2006;42:175–188. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. Parent-infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing: physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:329–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Eidelman AI, Sirota L, Weller A. Comparison of skin-to-skin (Kangaroo) and traditional care: parenting outcomes and preterm infant development. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):16–26. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Weller A, Sirota L, Eidelman AI. Testing a family intervention hypothesis: The contribution of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) to family interaction, proximity, and touch. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:94–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. Co-regulation coding system. University of Utah; 1994. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. Beyond individuals: a relational –historical approach to theory and research on communication. In: Genta ML, editor. Mother-infant communication. Carocci; Rome, IT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A, Garvey A. Alive Communication. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fohe K, Knopf S, Avenarious S. Skin-to-skin contact improves gas exchange in premature infants. Journal of Perinatology. 2000;20:311–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcada-Guex M, Pierrehumbert B, Borghini A, Moessinger A, Muller-Nix C. Early dyadic patterns of mother-infant interactions and outcomes of prematurity at 18 months. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e17–114. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz T, Black B, Scher M. Correlates of mother- premature – infant interactions. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30:333–346. doi: 10.1002/nur.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC, Fogel A. Stability and transitions in mother-infant face-to-face communication during the first 6 months: A microhistorical approach. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:1061–1082. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC, Jeng SF. Two-month-olds’ attention and affective response to maternal still face: a comparison between term and preterm infants in Taiwan. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC, Sung J. Separation anxiety in first-time mothers: infant behavioral reactivity and maternal parenting self-efficacy as contributors. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe F, Beebe B, Feldstein S, Crown CL, Jasnow MD. Rhythms of dialogue in infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2001. p. 66. 2 Serial No. 265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi LB, Stifter CA. Individual differences in the contribution of maternal soothing to infant distress in reduction. Infancy. 2007;11:255–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AN. The maternal experience of kangaroo holding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36:568–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinauskiene L, Cekuoliene D, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, Kusakovskaja I. Supporting insensitive mothers: the Vilnius randomized control trial of video-feedback intervention to promote maternal sensitivity and infant attachment security. Child: Care Health and Development. 2009;35(5):613–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00962.x. doi:10,1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00962x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korja R, Maunu J, Kirjavainen J, Savonlahti E, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, Manninen H, Piha J, Lehtonen L, the PIPARI Study Group Mother-infant interaction is influenced by the amount of holding in preterm infants. Early Human Development. 2008;84:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Emotional development in children with different attachment histories: The first three years. Child Development. 72:474–490. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legerstee M, Markova G, Fisher T. The role of maternal affect attunement in dyadic and triadic communication. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg B, Ohrling K. Experiences of having a prematurely born infant from the perspective of morhers in northern Sweden. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2008;67:461–471. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i5.18353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WF, Laudert S, Perkins B, MacMillan-York E, Martin S, Graven S. The development of potentially better practices to support the neurodevelopment of infants in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology. 2007;27:S48–S74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludington-Hoe SM, Johnson MW, Morgan K, Lewis T, Gutman J, Wilson PD, Scher MS. Neurophysiologic assessment of neonatal sleep organization: preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contact with preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e909–923. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth-LaForce C. Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:247–255. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GA, Calkins SD. Infants’ vagal regulation in the still-face paradigm is related to dyadic coordination of mother-infant interaction. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1068–1080. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A, Posada GE, Goldyn DT. Presence and quality of touch influence coregulation in mother-infant dyads. Infancy. 2006;9:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, Treas J. The 1989 socioeconomic index of occupations: Construction from the 1989 occupational prestige scores (General Social Survey Methodological Report No. 74) University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center; Chicago: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Neu M. Kangaroo care: is it for everyone? Neonatal Network. 2004;23(5):47–54. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.23.5.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu M. Parents’ perception of skin-to-skin care with their preterm infants requiring assisted ventilation. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 1999;28:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CL. Coregulation in moter-infant dyads: link to infants’ cardiac vagal tone. Psychological Reports. 2003;92:307–319. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roller CG. Getting to know you: mothers’ experiences of kangaroo care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34:210–217. doi: 10.1177/0884217504273675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Feldman JF, Jankowski JJ. Attention and recognition memory in the first year of life: A longitudinal study of preterms and full-terms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:135–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum KL, McDonough S, Muzik M, Miller A, Sameroff A. Maternal representations of the infant: associations with infant response to the still face. Child Development. 2002;73:999–1015. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal LB, Oster H, Cohen M, Caspi B, Myers M, Brown D. Smiling and fussing in seven-month-old preterm and full-term black infants in the still-face situation. Child Development. 1995;66:1829–1843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Bernard RS, Deblois T, Ikuta LM, Ginzburg K, Koopman C. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:131–137. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushane R, Vagg PH, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state trait anxiety inventory (form Y) University of South Florida; Tampa Florida: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner G, Spietz A. NCAST caregiver/parent-child interaction teaching manual. NCAST Publications, University of Washington, School of Nursing; Seattle: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ, Als H, Adamson L, Wise S, Brazelton TB. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1978;17:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)62273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ. Why is connection with others so critical? The formation of dyadic states of consciousness and the expansion of individuals’ states of consciousness: Coherence-governed selection and the cocreation of meaning out of messy meaning making. In: Nadel J, Muir D, editors. Emotional development: Recent research advances. Oxford University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. pp. 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ. The neurobehavioral and social-emotional development of infants and children. Norton; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ. Beyond the face: an empirical study of infant affective configurations of facial, vocal, gestural, and regulatory behaviors. Child Development. 1994;54:1503–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbilt D, Bushley T, Young R, Frank DA. Acute posttraumatic stress symptoms among urban mothers with newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit: a preliminary study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:50–56. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318196b0de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ. Infant affective reactions to the resumption of maternal interaction after the still-face. Child Development. 1996;67:905–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ, Beeghly M, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in postpartum women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:87–97. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Beeghly M, Tronick EZ. Making up is hard uto do, especially for mothers with high levels of depressive symptoms and their infant sons. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:670–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yato Y, Kawai M, Negayama K, Sogon S, Tomiwa K, Yamamoto H. Infant responses to maternal still-face at 4 and 9 months. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]