Abstract

Cell surface expression of MHC class I molecules by tumor cells is determinant in the interplay between tumor cells and the immune system. Nevertheless, the mechanisms which regulate MHCI expression on tumor cells are not clear. We previously showed that immune innate cells from the spleen can regulate MHCI expression on MHCIlow tumor cells. Here, using the murine model of B16 melanoma, we demonstrate that the MHCI status of tumor cells in vivo is regulated by the microenvironment. In subcutaneous grafts, induction of MHCI molecules on tumor cells is concomitant to the recruitment of lymphocytes and relies on an IFNγ-mediated mechanism. γδ T and NK cells are essential to this regulation. A small proportion of tumor-infiltrating NK cells and γδ T cells were found to produce IFNγ, suggesting a possible direct participation to the MHCI increase on the tumor cells upon tumor cell recognition. Depletion of γδ T cells increases the tumor growth rate, confirming their anti-tumoral role in our model. Taken together, our results demonstrate that in vivo, NK and γδ T cells play a dual role during the early growth of MHCIlow tumor cells. In addition to controlling the growth of tumor cells, they contribute to modifying the immunogenic profile of residual tumor cells.

Keywords: mice, B16 melanoma, MHC class I, NK cells, gamma delta T cells

Introduction

Cell surface expression of MHC class I molecules by tumor cells is thought to be an important determinant in the interplay between tumor cells and the immune system (1). When expressed on the cell surface, MHCI molecules allow antigen presentation that is required for target cell recognition by the cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Absence of MHCI molecules can trigger the innate part of the immune system by activating cells, such as NK cells, that express inhibitory receptors (KIRs) (2). Thus, the MHCI level on tumor cells participates in determining which arm of the immune system (adaptive or innate) can interact with tumor cells.

Different studies suggest that host factors are required to maintain a sustained MHCI level on tumors (3-5). Nevertheless, the mechanisms which regulate MHCI expression in vivo are not clear. Our present work aims at studying the early regulation of MHCI expression on tumor cells within their microenvironment. We hypothesized that the immune system itself plays an important role in this process. Firstly, the tumoral microenvironment includes immune components (6, 7) which participate in the dynamics of tumor cells/stroma interactions. Secondly, immune cells known to interact with tumor cells such as αβ T, γδ T, NKT, NK cells, macrophages and dendritic cells (8) are producers of IFNγ, which is one of the major external regulators of MHCI expression. Thirdly, we recently showed that NKT, DC and NK cells from normal non-immune spleen regulate MHCI expression in vitro on MHClow tumor cells by a cell-cell contact-dependent, IFNγ-mediated mechanism (9).

We took advantage of the murine melanoma B16F10 model and its fluorescent derivative B16F10-GFP (10) which express no or few MHCI molecules due to a reversible TAP2 deficiency (11). Fluorescent tumor cells were grafted in Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel matrix (12) in order to analyze both the modification of the MHCI level on tumor cells and the recruitment of immune host cells during the early steps of tumor growth. Using this model, we were able to show that the MHCI level can be rapidly upregulated on MHCIlow tumor cells when they grow in vivo. In the subcutaneous graft model, MHCI regulation is concomitant with the early phase of immune cell recruitment to the tumor site and depends on IFNγ. NK and γδ T cells are shown to be essential to this process. We discuss how this regulation could impact on tumor cell recognition and tumor growth or escape.

Results

MHCI level on B16F10 MHCI negative cells is upregulated in vivo

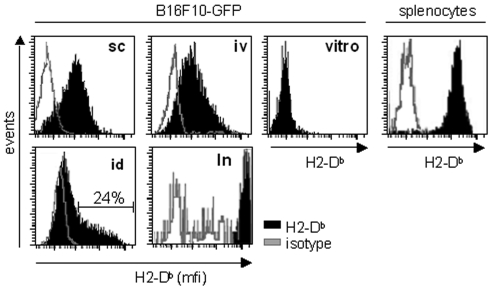

MHCI expression was examined on established tumors using the fluorescent tumor cell line B16F10-GFP (10). Similar to their parental cells, these cells express no MHCI molecules on their surface in vitro. B16F10-GFP cells were grafted in different locations and recovered ten days later. Figure 1 shows that tumor cells grown in vivo display a detectable level of MHCI molecules whatever the grafting site. The MHCI level was found to be homogeneous on cells extracted from subcutaneous tumor masses, experimental pulmonary metastases and spontaneous lymph node metastases that spread from the intradermal graft in the ear (Figure 1). In this latter model, only 24% of the cells from the primary tumor are MHCI+. It is noteworthy that spontaneous metastases found in lymph nodes display a very high level of MHCI molecules compared to normal cells such as the host splenocytes.

Figure 1.

Upregulation of MHCI expression on B16F10-GFP tumors in vivo. B16F10-GFP cells were injected subcutaneously (sc), via the tail vein (iv) or intradermally (id). Ten days later, tumor masses (sc, id), lungs (iv) and the lymph node draining the id tumor (ln) were recovered and dissociated. B16F10-GFP cells grown in vitro (vitro) and cells extracted from the mice spleens (splenocytes) were used as controls. Cell suspensions were labeled with anti-H2-Db antibody (black) or a control isotype (grey), followed by an APC-labeled secondary antibody. Fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry on DAPI negative B16F10-GFP cells.

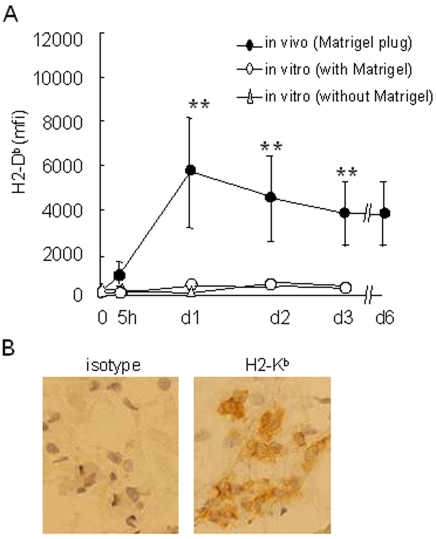

For the next experiments, we selected the subcutaneous model and injected the B16F10-GFP cells embedded in a matrix (Matrigel) in order to recover tumor cells and infiltrating host cells rapidly after the injection (13). An increase in the MHCI level was detectable as soon as 5 hours after the graft. It was found to be maximal at 24 hours and was stable over the period of tumor growth (Figure 2A). Matrigel does not interfere with the MHCI regulation on tumor cells since B16F10-GFP cells co-cultured with Matrigel do not upregulate their MHCI level. In vivo MHCI induction was also confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

MHCI upregulation occurs rapidly after the tumor cell graft. B16F10-GFP cells were injected subcutaneously in Matrigel at day 0. Mice were sacrificed at the times indicated and Matrigel plugs were resected and dissociated. As a control, B16F10-GFP cells were plated in vitro at day 0, with or without Matrigel. B16F10-GFP cells were analyzed for H2-Db expression as described in Figure 1. (A) Kinetics of H2-Db expression on B16F10-GFP cells extracted from Matrigel plugs (in vivo) or grown in vitro, with or without Matrigel. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate assays (**: P < 0.05). (B) Immunochemistry analysis of frozen sections from in vivo Matrigel plugs containing B16F10-GFP cells at day 3, immunostained with an anti-H2-Kb antibody.

Induction of MHCI molecules is concomitant to an immediate recruitment of lymphocytes toward melanoma cells

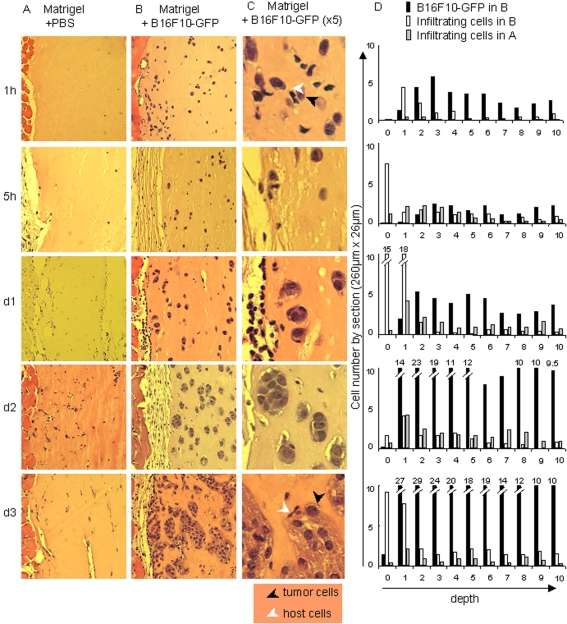

As shown in our previous study (9), immune cells can contribute to increase MHCI expression on tumor cells in vitro. Here, we analyzed the recruitment of host cells in Matrigel plugs in the subcutaneous graft model. Figure 3 shows an immunohistochemical analysis of control plugs (PBS) versus tumor plugs (B16F10-GFP), after hematoxylin and eosin labeling. The detected cells can basically be divided into two populations: (i) the tumor cells, characterized by a large pleomorphic nucleus and abundant cytoplasm containing finely dispersed melanin granules and (ii) the host cells (small size, small nucleus with a scant cytoplasm or large size, small nucleus with a more abundant pale cytoplasm for lymphocytes and macrophages respectively).

Figure 3.

MHCI upregulation is concomitant to host cell recruitment to the tumor site. Mice were injected either with PBS (A) or 5 x 105 B16F10-GFP cells (B-C) in Matrigel. At the times indicated, Matrigel plugs were resected, fixed and embedded in paraffin. Sections were labeled with hematoxylin and eosin (A-C). (C) Magnification (5x) of panel B. Black and white arrows indicate respectively tumor cells and infiltrating cells. (D) Tumor cells and infiltrating cells were counted in ten surface sections (260 µm x 26 µm) designed parallel to the edge, from the edge towards the center of the Matrigel plugs. Histograms show the number of B16F10-GFP cells (black bars) and infiltrating cells (white bars) in surface sections from one representative slice of six from two different Matrigel plugs containing tumor cells resected respectively at 1 h, 5 h, day 1, day 2 and day 3. The number of infiltrating cells in equivalent surface sections from one representative slice from two Matrigel plugs containing PBS only is shown as grey bars. Values are indicated above the bars when they are out of scale.

After injection, tumor cells are seen as isolated cells located homogeneously on the whole section surface. As soon as 1 h after the graft, host cells are infiltrating the tumor plugs but not the control plugs. Some of them establish close contact with the tumor cells (Figure 3C, 1 h). This very early invasion was confirmed by a semi-quantitative analysis of the histological data in which tumor cells and infiltrating cells were counted on successive slices, from the edge towards the center of the Matrigel plugs. As seen in Figure 3D (1 h, sections 1-4), infiltrating cells penetrate inside the tumor plugs and this tumor-specific recruitment is detected deeper in the plug at 5 h. At day 1 after injection small cellular islets appear, showing that tumor cells begin to divide while a second wave of host cells accumulate at the edge of the plug. A third tumor-specific recruitment is clearly seen at the edge, as well as in the depth of the tumor plug, at day 3.

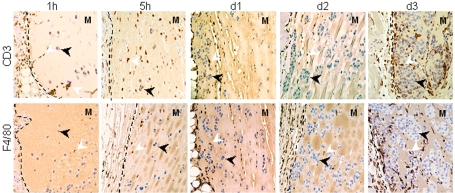

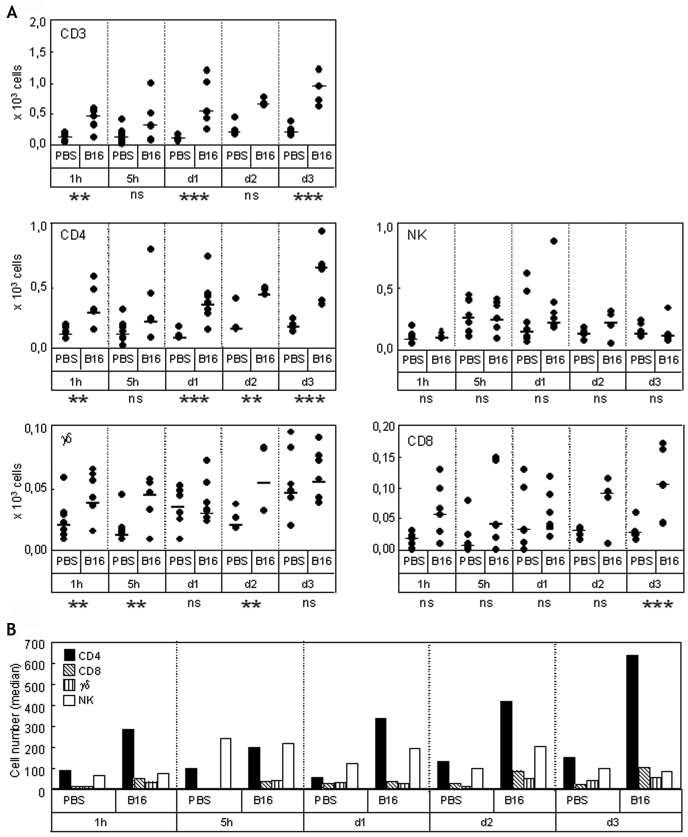

In a first step to identify the recruited cells, plugs sections were labeled with anti-CD3 or -F4/80 antibodies (Figure 4). CD3+ T cells begin to appear in tumor plugs from the edge at 1 h, and were clearly detected at 5 h, day 1 and day 3 inside the plugs. F4/80+ macrophages were detected from day 1 at the edge and infiltrated the tumor deeply at day 3. This analysis indicates that the cells that are accumulating predominantly during the phase of MHCI increase on tumor cells (i.e. during the first 24 hours after the graft) are mostly lymphocytes. This was extended by a flow cytometry analysis of plug contents. In plug extracts, tumor cells were distinguished from infiltrating cells on the basis of their high GFP fluorescence. Simultaneous labeling with anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -TCRγδ and -NK1.1 antibodies shows the recruitment of CD3+ T cells to the tumor site as soon as one hour after the graft (Figure 5A). Most of the CD3+ T cells were CD4+ T cells (Figure 5, panels A and B). Their recruitment was specifically induced by the presence of tumor cells since they were significantly more numerous in tumor plugs than in control ones. NK cells were the second most abundant cells found in tumor plugs, but they were also detected in control plugs. Interestingly, cells specifically recruited in tumor plugs at early times include a very small but significant amount of γδ T cells. CD8+ T cells were also detected and their recruitment appears to be tumor-specific only at day 3. We did not detect NKT (NK1.1+ CD3+) or IKDC (B220+ NK1.1+ CD11c+) cells.

Figure 4.

The early stage of tumor-specific recruitment concerns mostly lymphocytes. Mice were injected with 5 x 105 B16F10-GFP cells in Matrigel. At the times indicated, Matrigel plugs were resected, fixed, and embedded in paraffin. Matrigel sections were labeled with anti-CD3 or -F4/80 antibodies. Dotted lines indicate the edge of the Matrigel (M). Black and white arrows indicate tumor cells and CD3 or F4/80 positive cells respectively.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry analysis of lymphocytes involved in the early stages of tumor-specific recruitment. (A) Mice were injected either with PBS or 5 x 105 B16F10-GFP cells in Matrigel. At the times indicated, Matrigel plugs were resected and dissociated. Cellular suspensions were labeled with anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -NK, -TCRγδ antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For each condition, 5 to 6 independent Matrigel plugs were analyzed. The total number of cells (circles) recovered from each individual plug and the medians of mice groups (bars) are reported. For each time point, the significance of the difference between B16 groups and PBS groups was determined by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Abbreviations: ns, non significant; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.005. (B) Medians of the values in panel A are reported as histograms.

Endogenous IFNγ modulates MHCI molecules on tumor cells in vivo

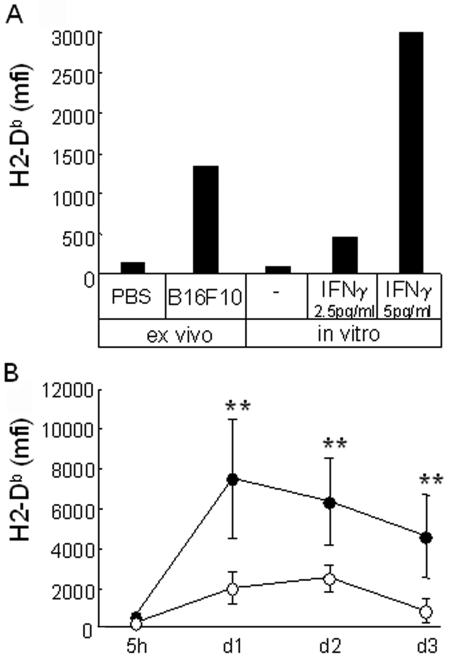

Matrigel plugs containing PBS or non-fluorescent B16F10 cells resected at day one after the graft were cultured in vitro with tumor cells. Figure 6A shows that extracted cells from tumor plugs, but not control plugs, induce MHCI expression on fresh B16F10-GFP in vitro. This suggests that plugs with tumor cells contained soluble or cellular elements able to regulate the MHCI level. It also confirms that the Matrigel matrix per se or the microenvironment locally induced in or around the Matrigel plug has no effect on the induction of MHCI molecules on the tumor cells.

Figure 6.

Endogenous IFNγ modulates MHCI molecules on tumor cells. (A) B16F10-GFP cells were co-cultured 2 days with extract of one day-plugs collected from mice injected either with PBS or non-fluorescent B16F10 cells (ex vivo), or with Matrigel containing IFNγ or not (in vitro). H2-Db expression was measured on B16F10-GFP cells. (B) B16F10-GFP cells were injected with Matrigel in C57Bl/6 or C57Bl/6 IFNγ0/0 mice (black or white circles, respectively; n = 5 or 6). At the times indicated, cells contained in the Matrigel were extracted and B16F10-GFP cells were analyzed for the expression of H2-Db. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate assays (Mann-Whitney rank sum test; **: P < 0.02).

Basal expression of MHCI molecules is known to be increased in response to IFNγ. Indeed, this is seen when B16F10-GFP cells are cultured with Matrigel containing added IFNγ (Figure 6A). We thus compared MHCI induction on B16F10-GFP, in wild-type and IFNγ0/0 mice. Figure 6B shows that the increase in MHCI molecules observed when tumor cells are grafted in C57Bl/6 mice is significantly lower when tumor cells grow on IFNγ0/0 mice. Thus, IFNγ participates to increase the level of MHCI molecules on B16F10 cells grown in vivo.

γδ T and NK cells are essential to upregulate the MHCI level on tumor cells in vivo

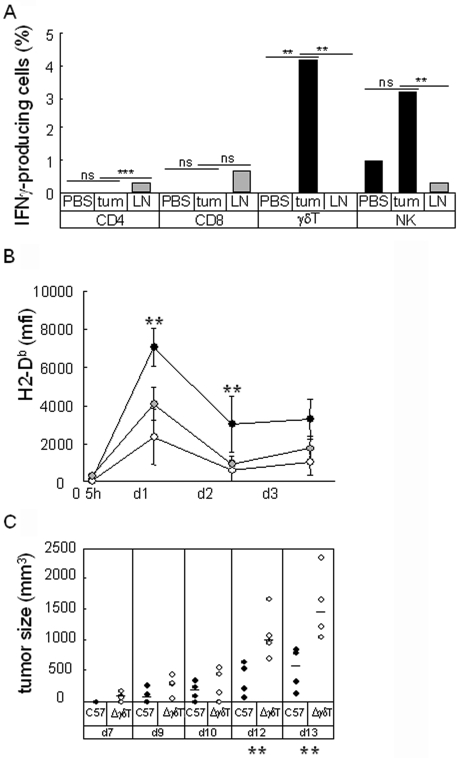

Upon IFNγ treatment in vitro, B16F10-GFP cells display a detectable MHCI level within 24 hours (data not shown). The similar kinetics observed in vivo suggest that tumor cells are in contact with IFNγ in the first hours following the graft. We tried to identify the source of the IFNγ by performing direct intracellular labeling of IFNγ on infiltrating cells extracted from pooled one-day plugs. Figure 7A shows that CD4+ T cells, which are the most abundant infiltrating cells, do not produce IFNγ at day 1. Despite the small number of cells analyzed, the proportions of IFNγ-producing cells among γδ T cells and NK cells were found to be consistently higher in tumor extracts than in PBS plugs or lymph node controls, suggesting that some of the cells recruited in plugs were stimulated to produce IFNγ in the presence of tumor cells.

Figure 7.

In vivo modulation of MHCI molecules expression is altered in TCRγ0/0 and NK-depleted mice. (A) B16F10-GFP cells or PBS were injected with Matrigel in C57Bl/6 mice. At day 1, cells contained in Matrigel plugs from five mice were extracted, pooled and labeled for intracellular IFNγ. The percentage of IFNγ positive cells in the indicated subsets are expressed as a histogram. Gating of IFNγ positive cells was defined using an isotypic control antibody. The significance of the differences in the percentage of positive cells was analyzed using a z-test (**: P < 0.05; ***: P < 0.005). (B) B16F10-GFP cells were injected with Matrigel in C57Bl/6 (black circles), TCRγ-depleted C57Bl/6 (white circles) and NK-depleted C57Bl/6 (grey circles) mice (n = 4). At the times indicated, cells contained in Matrigel were extracted and B16F10-GFP cells were analyzed for H2-Db expression. (C) B16F10-GFP cells were injected without Matrigel in C57Bl/6 (black circles) and TCRγ0/0 (white circles) mice (n = 4). Tumor growth is reported for the times indicated (**: P < 0.05).

We then analyzed MHCI expression on tumor cells grafted on γδ T cell- and NK cell-deficient mice. As shown on Figure 7B, upregulation of MHCI expression on tumor cells in vivo was severely impaired in the absence of either γδ T cells or NK cells in the first two days after the graft. γδ T cells seem to have a more drastic effect than NK cells. Because these cells were recently shown to participate to the tumor growth control, we compared the B16F10-GFP growth in normal or γδ T-deficient mice. Figure 7C shows that growth of B16F10-GFP tumor cells is delayed in normal mice compared to γδ T cell-deficient mice.

Discussion

We recently showed that the direct interaction of MHCIlow tumor cells with naive splenocytes in vitro induces the production of IFNγ, which upregulates the MHCI level on residual tumor cells. Because of the key role of MHCI expression in determining the interactions of tumor cells with the immune system, this prompted us to examine the relevance of such a regulating mechanism in vivo.

The B16F10 melanoma model we used was experimentally derived from a spontaneous melanoma in a C57Bl/6 mouse ear. Selected for its high ability to form pulmonary metastases (14), it differs from the primary tumor cell line (B16) by a loss of H-2 expression. As such, B16F10 cells are considered to be MHCIlow cells (11). Their susceptibility to the cytotoxic activity of NK cells (15-17) was well established and directly attributed to low expression of MHCI since they escape NK cytotoxicity when MHCI expression is restored (18, 19).

Different B16F10 graft models are used in order to mimic primary tumor growth, experimental or spontaneous tumor cell spreading (20). We found that when administered by subcutaneous, intravenous or intradermal route in non-immune syngeneic mice, B16F10 cells from established tumors upregulated the expression of MHCI molecules on their surface. This indicates that the MHCI status of tumor cells depends on their microenvironment.

In order to understand the mechanisms of this upregulation, we focused our analysis on a Matrigel subcutaneous model. Cells were grafted embedded in a Matrigel matrix, which is a soluble basement membrane derived from a murine tumor (12) and which facilitates the recovery of tumor cells and infiltrating cells (13). We compared the MHCI level on day 10 tumors that were injected subcutaneously, either embedded or not. We did not find any significant difference (data not shown), suggesting that Matrigel does not interfere in a major way with the MHCI regulation process in vivo. A bias in the nature and kinetics of host cell recruitment can not be completely excluded if Matrigel provides physical barriers for migrating cells (21). Nevertheless, it represents a genuine tumor cell microenvironment that is not expected to hinder cell migration. Our data (see below) and that of others (13, 21) indeed show that most of the immune subsets infiltrate Matrigel plugs. We thus assumed that mechanisms triggered in the Matrigel subcutaneous model are very similar to those occurring without Matrigel.

Using this model, we found that MHCI molecules begin to be upregulated as soon as host cells were recruited close to the tumor cells, i.e. during the hours following the graft. Many immune cells are known to be recruited to the nascent tumor site. NK cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) represent the first line of defense which is activated when tissue homeostasis is perturbed. NK and NKT cells participate in the cross-talk between innate and adaptive immunity by interacting with DCs (22). Acute activation of innate immunity sets the stage for activation of the adaptive immune system, i.e. of the αβ T cells.

A steady MHCI level was reached within 24 hours after the graft indicating that the triggering events precede this time point. The most abundant and earliest cells we could detect at the tumor site were CD4+ T cells and NK cells. Detection of CD4+ T cells was rather unexpected at such a very early phase of recruitment (1 h - 5 h) since they need to be properly activated in lymph nodes and to acquire a memory phenotype before patrolling in tissues. These cells are neither activated T cells nor regulatory T cells since they do not express the CD25 marker (data not shown). The significant increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at day 2 and day 3 after the graft fits better with the expected delay of the onset of an adaptive immune response. The detection of NK cells (at 5 h) and, in a smaller proportion, of γδ T cells (at 1 h and 5 h) is in agreement with the fact that NK and γδ T cells are regular constituents of normal skin with potential function in the clearance of tumor (23-26). Previous studies reported the infiltration of NKT cells (27) and IKDCs (B220+ NK1.1+ cells) (28) in B16 tumors. In this study, we did not detect any of these cell types during our time course analysis (3 days).

Upregulation of MHCI was severely impaired in IFNγ-deficient mice, demonstrating a predominant role of this cytokine, as previously shown in vitro (9). Nevertheless other physiological MHCI modulators, such as type I (α and β) interferons (29), might participate to a lesser extent to the MHCI regulation in vivo since it was not completely abrogated in IFNγ-deficient mice. The early timing of the regulation pointed to the innate immune cells as the IFNγ providers. NK and γδ T cells are mostly responsible for this effect since MHCI upregulation is also impaired in γδ T cell- and NK cell-deficient mice. Depletion of CD4+ T cells did not alter the MHCI induction on tumor cells (not shown), suggesting that no other cell subsets bearing the CD4+ marker (such as CD4+ NKT cells) are implicated. A very small proportion of tumor-infiltrating NK and γδ T cells were found to produce IFNγ at day one. The nature of the molecular signals that activate γδ T cells and NK cells in this model remains to be determined. Nevertheless, it was shown that B16 melanoma cells express Rae-1, a mouse MHC class Ib protein that engages the activating receptor NKG2D expressed on both subsets (30). No IFNγ producing cells were detected among early recruited CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells confirming that these detected cells were not specifically activated by the tumor cells. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing the role of NK cells on the regulation of MHCI molecules in vivo (31, 32). Nevertheless, this was observed in an IL-2-based therapy model where NK cells and tumor-associated macrophages were highly activated through recognition of an IL-2 cDNA-transduced B16 cell line. The implication of γδ T cells in MHCI regulation was not reported until now but these cells were previously described as an early source of IFNγ in tumor immunity (33).

Our experiments were set up in order to study the phenotypic changes on tumor cells that escaped the well-characterized NK response. This was achieved by injecting a number of tumor cells sufficient to overcome NK response efficiency and to induce tumor growth (34). Here, we show that depletion of γδ T cells increases the tumor growth rate, confirming their anti-tumoral role in our model, as previously described for an MHCI-expressing B16 variant grafted in the mice (33) or in human melanoma xenografts (24). Taken together, our results demonstrate that in vivo, NK and γδ T cells play a dual role during the early growth of MHCIlow melanoma cells. In addition to controlling the growth of tumor cells, they contribute to modifying their immunogenic profile through the production of IFNγ.

In our previous study (9), we proposed that in vitro MHCI upregulation on tumor cells was driven by a collaborative interaction between NKT cells (CD1d-independent CD4+), NK cells and DCs. It is noteworthy that, as a source of effectors cells, we used splenocytes where NKT and γδ T cells were equally represented and simultaneously in contact with the tumor cells. The major role we found for γδ T cells in vivo is consistent with the fact that, in addition to the functional properties shared with NK and NKT cells, some γδ T cells are resident in the epidermis and play a role in host resistance to carcinogenesis (25). NKT cells, which are barely present in the skin under normal conditions, may be recruited during the local immune reorganization that follows the activation of γδ T cells (35). Interestingly, DCs were detected in tumor plugs at day 1 (data not shown) simultaneously with IFNγ-producing γδ T cells. From our in vitro model, we proposed that the IFNγ produced by NKT and NK cells stimulates DCs to secrete IL-12, which in turn sustains the IFNγ production by NK and NKT cells. A similar reciprocal activating interaction was described between γδ T cells and DCs (36, 37), suggesting that the DCs recruited to the tumor site may also participate in such an interplay in vivo. If this is the case, one would expect reduced MHCI regulation in an IL-12 deficient mouse.

Because the initial response to tumor cells may depend mainly on the local, tissue-associated immune cells, different innate immune subsets may be engaged from one graft location to another. While not explored for NKT cells or circulating γδ T cells, it was shown that NK cells are recruited very rapidly in the lung after an i.v. graft (17) and thus could also play a role in the MHCI upregulation we observed in the lung tumoral foci. Surprisingly, the MHCI level on tumor cells was found to be rather elevated in lymph nodes, in which NK, NKT and γδ T cells are poorly represented subsets. We nevertheless observed that a significant proportion of the CD4+ T cells found in tumor draining lymph nodes produced IFNγ. This suggests that various sources of IFNγ participate to modify the tumor phenotype and to sustain these changes during the tumor growth, depending on the tissue that surrounds the tumor cells and the proximity of activated IFNγ-producing cells.

The MHCI modulation observed on the B16F10 melanoma upon interaction with the innate immune effectors would presumably also occur with other MHCIlow tumor cells, such as methylcholanthrene (MCA)-induced sarcomas. While not shown here, this is strongly suggested by the splenocyte-induced modulation that we observed in vitro on the MCA102 cell line (9). Furthermore, the activation of innate immune effectors and their protective role against MCA-induced tumors via IFNγ production is well documented (25, 33, 38). What can be the consequences of such a MHCI upregulation? MHCI expression on tumor cells is by itself a known escape mechanism to NK cells. Indeed, metastatic ability has been correlated to an increase in the H-2 antigen expression and the decrease in sensitivity to the NK cell. In contrast, upregulation of the level of MHCI molecules on B16F10 cells by IFNγ treatment is known to improve their recognition and lysis by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in vitro (9). Production of IFNγ by γδ T cells was also shown to participate to the onset of the adaptive response (33). Thus, these simultaneous effects on the MHCI level of tumor cells and on the activation of effectors could support the transition from an innate response towards an efficient adaptive anti-tumoral response in vivo. Nevertheless, the time course we observed in this study shows that the completion of MHCI upregulation occurs 24 h - 48 h before the time required for the onset of an efficient adaptive response. During this time, tumor cells that survived the innate immune effectors actively proliferate and might acquire at least a numerical advantage against the adaptive response. Furthermore, IFNγ is known to have several inhibitory effects on tumor cell killing by cytotoxic cells. By downregulating the expression of NKG2D ligands on melanoma cells (39-41), IFNγ impairs the cytotoxic activity not only of NK cells (42) but also of CTLs and γδ T cells in which NKG2D acts as a co-stimulatory receptor (43). It has also been shown to hamper the granzyme B association with the target cell membrane in an uveal melanoma cell model (44).

B16F10 cells are indeed known to be poor spontaneous stimulators of the adaptive response in vivo and efficient tumor eradication by CD8+ T cells operates only in hosts that have been previously immunized (45-48). Whether or not IFNγ participates directly to the escape of tumor cells through its role in the in situ modulation of the tumor phenotype remains to be determined. The concept of cancer immunoediting proposes that the immune system plays an active role in tumor progression, during the phases of elimination, equilibrium and escape (38, 49). Our results, as well as those of others, support the idea that in addition to genetic or epigenetic changes resulting in stable cellular phenotypes, immunoediting also involves an inducible modulation of tumor cells in response to a microenvironment associated with the immune activation. Thus, in order to improve treatment outcomes, the tumor phenotype should be carefully monitored and possibly pharmacologically modulated, depending on its evolving microenvironment and the immuno- or chemo-therapeutic options (50).

Abbreviations

- MHCI

MHC class I

Acknowledgements

We thank Jean Christophe Blanchet and Florence Capilla for histological and immunohistochemical experiments, William Riquet for antibody production, Bent Rubin, Myriam Capone, Julie Déchanet-Merville and Jean-Jacques Fournié for their helpful discussions. This work was supported by institutional grants from the CNRS, Laboratoires Pierre Fabre, and from the European Union.

References

- 1.Aptsiauri N, Cabrera T, Garcia-Lora A, Lopez-Nevot MA, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens and immune surveillance in transformed cells. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;256:139–189. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)56005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diefenbach A, Raulet DH. The innate immune response to tumors and its role in the induction of T-cell immunity. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:9–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finn OL, Lieberman M, Kaplan HS. H-2:antigen expression: loss in vitro, restoration in vivo, and correlation with cell-mediated cytotoxicity in a mouse lymphoma line. Immunogenetics. 1978;7:79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF01843991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtkamp B, Fischer-Lindahl K, Segal M, Rajewski K. Spontaneous loss and subsequent stimulation of H-2 expression in clones of a heterozygous lymphoma line. Immunogenetics. 1979;9:405–421. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker S, Kiessling R, Lee N, Klein G. Modulation of sensitivity to natural killer cell lysis after in vitro explantation of a mouse lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978;61:1495–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zitvogel L, Tesniere A, Kroemer G. Cancer despite immunosurveillance: immunoselection and immunosubversion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nri1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdan C, Schleicher U. Production of interferon-gamma by myeloid cells--fact or fancy? Trends Immunol. 2006;27:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin B, Riond J, Courtiade L, Roullet N, Gairin JE. The innate immune system recognizes and regulates major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI) expression on MHCIlow tumor cells. Cancer Immun. 2008;8:14. http://www.cancerimmunity.org/v8p14/080814.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golzio M, Mazzolini L, Ledoux A, Paganin A, Izard M, Hellaudais L, Bieth A, Pillaire MJ, Cazaux C, Hoffmann JS, Couderc B, Teissié J. In vivo gene silencing in solid tumors by targeted electrically mediated siRNA delivery. Gene Ther. 2007;14:752–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seliger B, Wollscheid U, Momburg F, Blankenstein T, Huber C. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex class I deficiencies in B16 melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1095–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman HK, McGarvey ML, Hassell JR, Star VL, Cannon FB, Laurie GW, Martin GR. Basement membrane complexes with biological activity. Biochemistry. 1986;25:312–318. doi: 10.1021/bi00350a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corthay A, Skovseth DK, Lundin KU, Røsjø E, Omholt H, Hofgaard PO, Haraldsen G, Bogen B. Primary antitumor immune response mediated by CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2005;22:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidler IJ. Tumor heterogeneity and the biology of cancer invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 1978;38:2651–2660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fogler WE, Volker K, McCormick KL, Watanabe M, Ortaldo JR, Wiltrout RH. NK cell infiltration into lung, liver, and subcutaneous B16 melanoma is mediated by VCAM-1/VLA-4 interaction. J Immunol. 1996;156:4707–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smyth MJ, Thia KY, Street SE, Cretney E, Trapani JA, Taniguchi M, Kawano T, Pelikan SB, Crowe NY, Godfrey DI. Differential tumor surveillance by natural killer (NK) and NKT cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:661–668. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundy MA, Zhang T, Sentman CL. NK cells rapidly remove B16F10 tumor cells in a perforin and interferon-gamma independent manner in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1153–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0264-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljunggren HG, Sturmhöfel K, Wolpert E, Hämmerling GJ, Kärre K. Transfection of beta 2-microglobulin restores IFN-mediated protection from natural killer cell lysis in YAC-1 lymphoma variants. J Immunol. 1990;145:380–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franksson L, George E, Powis S, Butcher G, Howard J, Kärre K. Tumorigenicity conferred to lymphoma mutant by major histocompatibility complex-encoded transporter gene. J Exp Med. 1993;177:201–205. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee L, Sharma S, Morgan B, Allegrini P, Schnell C, Brueggen J, Cozens R, Horsfield M, Guenther C, Steward WP, Drevs J, Lebwohl D, Wood J, McSheehy PM. Biomarkers for assessment of pharmacologic activity for a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitor, PTK787/ZK 222584 (PTK/ZK): translation of biological activity in a mouse melanoma metastasis model to phase I studies in patients with advanced colorectal cancer with liver metastases. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:761–771. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albertsson P, Basse PH, Edsparr K, Kim MH, Goldfarb RH, Kitson RP, Lennernäs B, Nannmark U, Johansson BR. Differential locomotion of long- and short-term IL-2-activated murine natural killer cells in a model matrix environment. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:402–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cells in tumor immunity: opposing subsets define a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2008;180:3627–3635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebert LM, Meuter S, Moser B. Homing and function of human skin gammadelta T cells and NK cells: relevance for tumor surveillance. J Immunol. 2006;176:4331–4336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozupone F, Pende D, Burgio VL, Castelli C, Spada M, Venditti M, Luciani F, Lugini L, Federici C, Ramoni C, Rivoltini L, Parmiani G, Belardelli F, Rivera P, Marcenaro S, Moretta L, Fais S. Effect of human natural killer and gammadelta T cells on the growth of human autologous melanoma xenografts in SCID mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:378–385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girardi M, Oppenheim DE, Steele CR, Lewis JM, Glusac E, Filler R, Hobby P, Sutton B, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science. 2001;294:605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1063916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamada K, Harada M, Abe K, Li T, Tada H, Onoe Y, Nomoto K. Immunosuppressive activity of cloned natural killer (NK1.1+) T cells established from murine tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:4846–4854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taieb J, Chaput N, Ménard C, Apetoh L, Ullrich E, Bonmort M, Péquignot M, Casares N, Terme M, Flament C, Opolon P, Lecluse Y, Métivier D, Tomasello E, Vivier E, Ghiringhelli F, Martin F, Klatzmann D, Poynard T, Tursz T, Raposo G, Yagita H, Ryffel B, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. A novel dendritic cell subset involved in tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Med. 2006;12:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nm1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka K, Yoshioka T, Bieberich C, Jay G. Role of the major histocompatibility complex class I antigens in tumor growth and metastasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:359–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akao Y, Ebihara T, Masuda H, Saeki Y, Akazawa T, Hazeki K, Hazeki O, Matsumoto M, Seya T. Enhancement of antitumor natural killer cell activation by orally administered Spirulina extract in mice. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1494–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kijima M, Saio M, Oyang GF, Suwa T, Miyauchi R, Kojima Y, Imai H, Nakagawa J, Nonaka K, Umemura N, Nishimura T, Takami T. Natural killer cells play a role in MHC class I in vivo induction in tumor cells that are MHC negative in vitro. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:679–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouyang GF, Saio M, Suwa T, Imai H, Nakagawa J, Nonaka K, Umemura N, Kijima M, Takami T. Interleukin-2 augmented activation of tumor associated macrophage plays the main role in MHC class I in vivo induction in tumor cells that are MHC negative in vitro. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Yang W, Pan M, Scully E, Girardi M, Augenlicht LH, Craft J, Yin Z. Gamma delta T cells provide an early source of interferon gamma in tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2003;198:433–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smyth MJ, Taniguchi M, Street SE. The anti-tumor activity of IL-12: mechanisms of innate immunity that are model and dose dependent. J Immunol. 2000;165:2665–2670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strid J, Roberts SJ, Filler RB, Lewis JM, Kwong BY, Schpero W, Kaplan DH, Hayday AC, Girardi M. Acute upregulation of an NKG2D ligand promotes rapid reorganization of a local immune compartment with pleiotropic effects on carcinogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:146–154. doi: 10.1038/ni1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Münz C, Steinman RM, Fujii S. Dendritic cell maturation by innate lymphocytes: coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:203–207. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conti L, Casetti R, Cardone M, Varano B, Martino A, Belardelli F, Poccia F, Gessani S. Reciprocal activating interaction between dendritic cells and pamidronate-stimulated gammadelta T cells: role of CD86 and inflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;174:252–260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bui JD, Carayannopoulos LN, Lanier LL, Yokoyama WM, Schreiber RD. IFN-dependent down-regulation of the NKG2D ligand H60 on tumors. J Immunol. 2006;176:905–913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwinn N, Vokhminova D, Sucker A, Textor S, Striegel S, Moll I, Nausch N, Tuettenberg J, Steinle A, Cerwenka A, Schadendorf D, Paschen A. Interferon-gamma down-regulates NKG2D ligand expression and impairs the NKG2D-mediated cytolysis of MHC class I-deficient melanoma by natural killer cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1594–1604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav D, Ngolab J, Lim RS, Krishnamurthy S, Bui JD. Cutting edge: down-regulation of MHC class I-related chain A on tumor cells by IFN-gamma-induced microRNA. J Immunol. 2009;182:39–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang C, Niu J, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Tian Z. Opposing effects of interferon-alpha and interferon-gamma on the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related A in tumors. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1279–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maccalli C, Nonaka D, Piris A, Pende D, Rivoltini L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. NKG2D-mediated antitumor activity by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and antigen-specific T-cell clones isolated from melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7459–7468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallermalm K, Seki K, De Geer A, Motyka B, Bleackley RC, Jager MJ, Froelich CJ, Kiessling R, Levitsky V, Levitskaya J. Modulation of the tumor cell phenotype by IFN-gamma results in resistance of uveal melanoma cells to granule-mediated lysis by cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:3766–3774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldszmid RS, Idoyaga J, Bravo AI, Steinman R, Mordoh J, Wainstok R. Dendritic cells charged with apoptotic tumor cells induce long-lived protective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immunity against B16 melanoma. J Immunol. 2003;171:5940–5947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibagaki N, Udey MC. Dendritic cells transduced with TAT protein transduction domain-containing tyrosinase-related protein 2 vaccinate against murine melanoma. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:850–860. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He Y, Zhang J, Mi Z, Robbins P, Falo LD Jr. Immunization with lentiviral vector-transduced dendritic cells induces strong and long-lasting T cell responses and therapeutic immunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:3808–3817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KC, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, Diamond MS, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM, Schreiber RD. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ni1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zitvogel L, Tesniere A, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Kroemer G. [Immunological aspects of anticancer chemotherapy]. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2008;192:1469–1487. Discussion 1487-1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Materials and methods

Mice

C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Janvier (Le Genest-St-Isle, France), IFNγ0/0 mice were obtained from INSERM-IFR30 (Toulouse, France), and TCRδ0/0 mice were a generous gift from M. Capone (UMR5164, CNRS-Université Bordeaux 2, France). Animals used in experiments were between 7 and 12 weeks of age. All experiments were approved by the "Comité d'éthique pour l'expérimentation animale" of the CNRS.

In vivo depletion

Anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136) antibodies were purified from ATCC hybridoma supernatants. Mice were depleted of NK cells by intraperitoneal injections of 250 µg of antibody at day -3 and day -1 before tumor cell graft (day 0). When indicated, an additional injection was performed at day +1.

Tumor cell line and experimental in vivo models

B16F10-GFP cells were grown in vitro in RPMI medium supplemented with Glutamax (Gibco Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), complement-free fetal calf serum (10%), and antibiotics (10 IU/ml penicillin and 10 µg/ml streptomycin). For injection, they were mildly dissociated with trypsin/EDTA and washed twice with PBS. Viability was more than 90%. Cells were injected in PBS via the tail vein (5 x 105 cells), subcutaneously on the flank (5 x 105 cells) or intradermally in the ear (2 x 105 cells). When indicated, B16F10-GFP (5 x 105 cells in 50 µl PBS) were mixed with 100 µl Matrigel (Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel, BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France) and injected subcutaneously in C57/Bl6 mice.

Ex vivo analysis of MHCI expression by flow cytometry

Tumors, Matrigel plugs, lungs or lymph nodes were recovered and minced in 600 µl dispase (BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France) for 30 min at 37˚C. Digestion was stopped with medium. Samples were filtered on 75 µm filters and washed twice. Extracted cells were labeled with anti-H2-Db antibody (clone 28-14-8s) or a control isotype (0.5 µg/ml) and with an allophycocyanin (APC)-donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (2.5 µg/ml, eBioscience-Clinisciences, Montrouge, France) in PBS containing 1% BSA. After washes, they were labeled with DAPI (2 µg/ml) in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII, BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France). APC fluorescence was measured on GFP cells that are DAPI negative.

Ex vivo analysis by immunohistochemistry

Tumors plugs were either snap frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histomorphological analyses.

For MHCI analysis, frozen sections were first incubated with a biotinylated anti-H2-Kb monoclonal antibody (clone AF6-88.5; BD Pharmingen, Le Pont-de-Claix, France), followed by a biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase complex (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and the diaminobenzidine chromogen solution. Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin. Non-reactive immunoglobulin of the same isotype was included as a negative control.

Immunostaining of T cells and macrophages was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the rabbit polyclonal anti-CD3 antibody (Dako) or with the rat monoclonal anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (clone CI :A3-1; AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) respectively. CD3 staining was carried out with ImmPRESS anti-rabbit Ig (peroxidase) reagent (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, USA) after antigen retrieval in target retrieval solution pH 6 (S 1700, Dako) for 40 min at 95˚C. F4/80 staining was obtained after treatment with trypsin (1 mg/ml) for 6 min at 37˚C and completed with a biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase complex as described above. Mononuclear cells were counted in representative high-power fields (400x). Negative controls were incubated in buffered solution without primary antibodies.

Tumor infiltrate analysis

Mice were sacrificed and Matrigel plugs were recovered. They were minced and extracted twice with 600 µl of Cell Recovery solution (BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France) upon mild agitation during 30 min at 4˚C. Residual pieces were treated 5 min at 37˚C with trypsin/EDTA (Gibco Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France). Supernatants were pooled and added to a known number of beads (negative control of BD CompBeads; BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France). They were then filtered on 75 µm filters (BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France), centrifuged and washed twice with complete medium.

Cellular suspensions were labeled with fluorescent antibodies. Anti-CD3e-PE-Cy7 (clone 145-2C11), -CD4-Aexa 700 (clone RM4-5), -CD8-PE-Cy5 (clone 53-6.7), -TCRγδ-FITC (clone GL3), -NK-1.1-PE (clone PK136), -B220-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone RA3-6B2) antibodies were from BD Biosciences (Le-Pont-de-Claix, France). Cell subsets were identified and counted by flow cytometry, using beads as an internal standard.

When intracellular IFNγ staining was performed, labeled cellular suspensions were fixed with paraformaldehyde, saponin-permeabilized and stained with either an anti-mouse IFNγ antibody (clone XMG1.2) or an isotype control (clone R3-34) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (BD Biosciences, Le Pont-de-Claix, France).

Statistic analysis

Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Results expressed as percentages were analyzed using the z-test. Both tests were done with the SigmaStat software (Systat Software, Inc, Point Richmond, USA).