Summary

Obesity is associated with insulin resistance in metabolic tissues such as adipose, liver, and muscle, but it is unclear whether non-classical target tissues, such as those of the reproductive axis, are also insulin resistant. To determine if the reproductive axis maintains insulin sensitivity in obesity in vivo, murine models of diet-induced obesity with and without intact insulin signaling in pituitary gonadotrophs were created. Diet-induced obese wild type female mice (WT DIO) were infertile and experienced a robust increase in luteinizing hormone (LH) after gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) or insulin stimulation. By contrast, both lean and obese mice with a pituitary-specific knockout of the insulin receptor (PitIRKO) exhibited reproductive competency, indicating that insulin signaling in the pituitary is required for the reproductive impairment seen in diet-induced obesity and that the gonadotroph maintains insulin sensitivity in a setting of peripheral insulin resistance.

Introduction

Nutritional status is tightly coupled to reproductive function. Short-term and chronic withdrawal of nutrients is known to inhibit reproductive function in mammals (Cameron and Nosbisch, 1991), likely an evolutionary adaptation to the large amount of energy required for reproduction. In addition, conditions of excess nutrition, such as obesity, have also been linked to reproductive dysfunction. Infertility is associated with conditions such as type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). These conditions are marked by obesity and a complex metabolic phenotype that includes hyperinsulinemia, hyperleptinemia, as well as insulin and leptin resistance. Of these metabolic disorders linked to infertility, PCOS is the best characterized and is the most common cause of infertility in women. In addition to obesity and hyperinsulinemia, PCOS is associated with anovulation and elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) levels suggesting that the central reproductive axis is tonically activated, leading to ovarian dysfunction.

We and others have shown that insulin and insulin-like growth factors can augment the effects of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) on LH expression and secretion (Adashi et al., 1981; Buggs et al., 2006; Soldani et al., 1995) in vitro using LH-secreting gonadotroph cell lines, suggesting that direct insulin action in the gonadotroph may contribute to the elevated LH observed in women with PCOS. In contrast to studies showing that insulin can augment GnRH (Buggs et al., 2006), GnRH has also been shown to inhibit an insulin response in vitro (Navratil et al., 2009). Some groups have noted that in PCOS women, insulin injection caused circulating gonadotropin levels to decrease (Lawson et al., 2008; Mehta et al., 2005; Patel et al., 2003). This suggests that the dysregulation of LH synthesis and/or release in PCOS may be due to insulin dysregulation at the level of the gonadotroph; however, whether the central reproductive tissues maintain insulin sensitivity in the presence of hyperinsulinemia and peripheral insulin resistance remains unclear. While women with PCOS and infertility display insulin resistance in insulin target tissues such as liver and muscle, it is unknown whether the central reproductive axis is also insulin resistant. Approaching this question has been hampered by the difficulty in generating a rodent model to mimic the complex phenotype of PCOS. Mixed results have stemmed from attempts to model the obese, infertile state, and some mouse strains have reacted differently to the effects of a high fat diet (Tortoriello et al., 2004). Consequently, a clear view of nutritional regulation of the reproductive axis has yet to be defined.

Given the discrepant in vitro observations of the gonadotroph response to insulin, we chose to focus on isolating the role of insulin in vivo in the reproductive axis as an important signaling factor of over-nutrition. To determine the direct effects of insulin on the gonadotroph, our laboratory has developed a pituitary-specific insulin receptor (IR) knockout (KO), or PitIRKO mouse. In this study, we use the PitIRKO model to directly assess the role of insulin signaling in the pituitary gonadotroph in the context of infertility associated with diet-induced obesity (DIO).

Results

Generation of PitIRKO Mice

Pituitary-specific insulin receptor knockout (PitIRKO) mice were generated by breeding homozygous floxed IR mice (Bruning et al., 2000) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the promoter of the alpha subunit of gonadotropins (αGSU) to target the anterior pituitary (Naik et al., 2006). Our model (Singh et al., 2009) and others targeting the same cell types (Savage et al., 2007) have been shown to specifically target gonadotrophs. PitIRKO Mice were born with the expected Mendelian frequency and were of normal size and weight. Mice were genotyped using a PCR strategy schematized in Figure 1. Upon expression of the Cre recombinase enzyme, exon 4 of the IR is excised resulting in loss of function of the IR. The PCR product indicating the homozygous floxed-IR alleles (320 bp) were present in all tissues, while a KO specific band (220 bp) was present only in the pituitary (Figure 1B). In the pituitary, the two products, indicating presence of the floxed alleles and the KO specific band, appeared as a result of the mixed cell population present in the pituitary.

Figure 1. Development of pituitary-specific IR knockout mouse.

(A) Mouse insulin receptor gene. Mice bearing LoxP sites flanking exon 4 of the insulin receptor were crossed with mice carrying common alpha subunit-driven Cre recombinase to generate pituitary-specific knockdown of the insulin receptor, or PitIRKO. Primers P1 and P2 were designed to indicate the presence of the LoxP site 3’ of exon 4. Primer P3 and P2 produce a band following Cre recombination. (B) PCR reaction performed on genomic DNA from various tissues indicating the presence of homozyogous floxed alleles (320 bp) in all tissues and the knockout (KO) product following Cre recombination in the pituitary (220 bp).

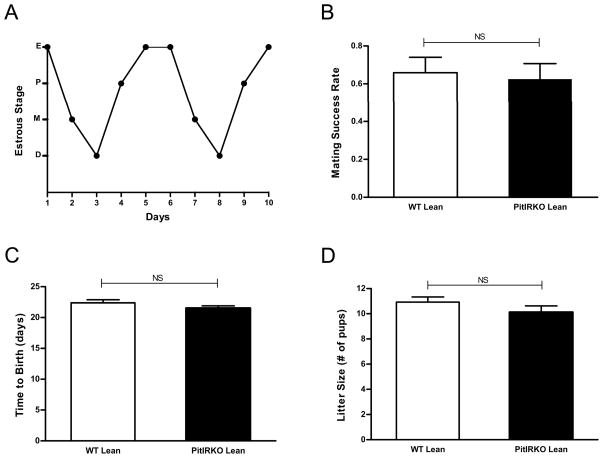

Lean PitIRKO females have normal reproductive function

Reproductive function of lean PitIRKO females was assessed via evaluating estrous cyclicity and breeding studies. Ten lean PitIRKO females were analyzed for vaginal cytology over the course of ten days and each displayed a regular pattern of cycling, passing through each stage of the estrous cycle and only remaining in any one stage for 1-2 days as represented by the plot in Figure 2A. Mating of PitIRKO lean females with WT proven fertile males showed no differences in breeding success rate, number of pups per litter, or length of gestation compared to littermate controls (Figure 2B, C and D).

Figure 2. Reproductive assessment of lean PitIRKO female mice.

(A) Representative vaginal cytology plot from a lean PitIRKO female mouse. Eight PitIRKO females were analyzed and each showed a regular cycling pattern. (B) Percent of litter-producing matings by PitIRKO lean females and WT lean females (C) Gestation periods (D) Litter sizes. WT lean N=13 PitIRKO lean N=10. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

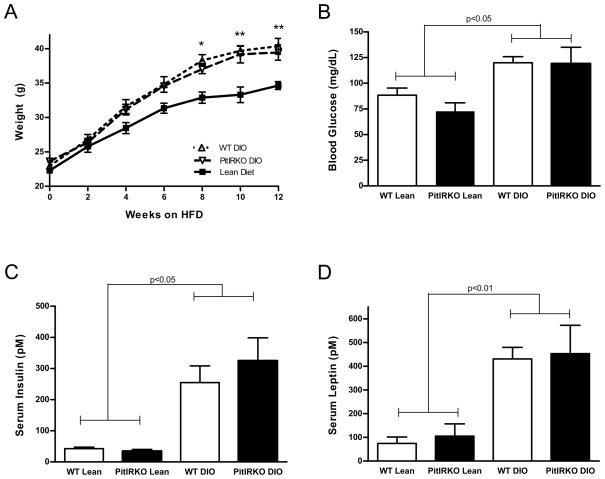

Diet induced obese mice display hallmarks of insulin resistance

At 8 weeks of age, WT and PitIRKO mice were placed on a high fat (60% Kcal from fat) diet and maintained on the high fat diet for 12 weeks prior to evaluation. Diet induced obese (DIO) mice were evaluated for weight gain over the course of the 12-week period and fasting glucose, insulin, and leptin levels were then determined. Mice fed a regular chow diet had a range of weight gain between 10 and 15 grams while DIO mice gained between 17 and 23 grams over the twelve-week period (Figure 3A). Both WT and PitIRKO DIO mice displayed significantly higher fasting blood glucose, insulin levels, and leptin levels than lean mice, indicating that loss of the IR in the gonadotroph does not affect peripheral glucose metabolism (Figure 3B-D).

Figure 3. Diet Induced Obesity model (DIO).

(A) Total body weight of WT lean, PitIRKO lean, WT DIO, and PitIRKO DIO mice over the course of twelve weeks. (B) Fasting blood glucose levels, (C) fasting serum insulin levels, and (D) fasting serum leptin levels across groups. WT lean N=12, PitIRKO lean N=8, WT DIO N=25, PitIRKO DIO N=10. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between lean and DIO: * p-value less than 0.05, ** p-value less than 0.01.

The gonadotroph insulin receptor regulates LH secretion from the pituitary on an obese, hyperinsulinemic background

Baseline serum LH levels were nearly doubled in WT DIO mice compared to WT lean controls (Figure 4A). Although serum FSH levels were elevated by nearly 40% in WT DIO mice compared to WT lean mice, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 4B). While there was no significant difference in baseline LH levels in the presence or absence of IR in the gonadotroph in the chow-fed female mice, serum LH levels were lower in the PitIRKO DIO than in WT DIO mice (Figure 4A). The LH levels in the PitIRKO DIO mice were not different from baseline levels observed in chow fed female mice. To determine whether differences in gene expression contributed to the differences in observed LH levels, quantitative PCR was performed on pituitaries collected from each group. Relative alpha subunit (αGSU) and the LH-β subunit mRNA was assessed and both showed increased basal levels in the WT DIO mice (Figure 4C and D). Both PitIRKO lean and PitIRKO DIO females had serum LH and mRNA levels similar to the WT lean group, and significantly lower levels than WT DIO. We also observed a statistically significant (p<0.05) increase in serum testosterone in WT DIO females (19.3ng/dL, N=25) relative to lean WT females (10.4ng/dL, N=12) suggesting that diet induced obesity in our strain of mice is a suitable model of PCOS.

Figure 4. Basal gonadotropin levels are elevated in WT DIO mice, and WT DIO mice are the most responsive to GnRH stimulation.

(A) Baseline serum luteinizing hormone (LH) levels across groups. Assay detection limit = 0.048ng/mL. (B) Baseline follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels across groups. Assay detection limit = 0.032ng/mL. WT lean N=12, PitIRKO lean N=10, WT DIO N=24, PitIRKO DIO N=10. (C) Basal relative αGSU and (D) LH-β mRNA levels across groups. (E) Fold change in serum LH following injection of GnRH. (F) Basal relative GnRH Receptor mRNA levels. (G) GAPDH was also measured as an unregulated control. WT lean N=11-16, PitIRKO lean=7–8, WT DIO N=12–19, PitIRKO DIO N=8–10. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

WT DIO mice are more responsive to GnRH stimulation than WT lean mice due to upregulation of the GnRH-Receptor

Previous studies have indicated that insulin augments GnRH stimulation of LHβ gene expression and LH secretion (Buggs et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2001). To explore the effect of obesity and hyperinsulinemia on GnRH-induced LH release from the pituitary, a GnRH stimulation test was performed. WT and PitIRKO lean mice both experienced an eight-fold increase in LH after GnRH stimulation while WT DIO mice had an approximately sixteen-fold increase (Figure 4E). In contrast to WT DIO mice showing an increased response to GnRH stimulation, PitIRKO DIO mice had a significantly reduced GnRH response with only a three-fold increase in serum LH following GnRH stimulation. To investigate a potential mechanism for the increased sensitivity to GnRH in the WT DIO mice, relative baseline GnRH-R mRNA levels were compared across groups. Baseline GnRH-R mRNA levels were more than fourteen-fold higher in WT DIO versus other groups (Figure 4F). GAPDH was used as a control and was not significantly different among groups (Figure 4G).

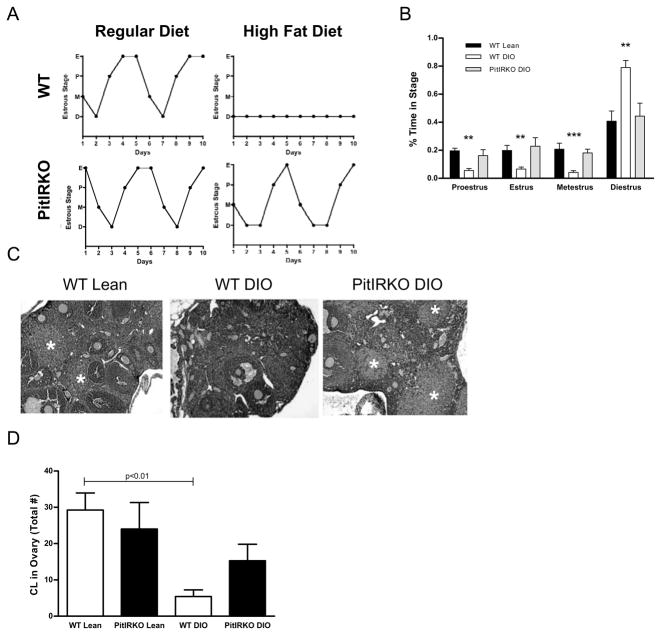

WT DIO female mice display irregular estrous cyclicity and develop fewer corpora lutea while cyclicity and corpora lutea are retained in PitIRKO DIO mice

Estrous cyclicity was examined to evaluate ability to generate an LH surge and induce ovulation. WT and PitIRKO lean females cycled regularly, while WT DIO animals remained in the diestrus phase of the estrous cycle (Figure 5A). Interestingly, PitIRKO DIO females retained their cyclicity, showing a regular cycling pattern comparable to the WT lean and PitIRKO lean females (Figure 5A). WT DIO mice spent a significantly higher percentage of time in the diestrus phase than lean controls and PitIRKO DIO mice, and a significantly lower percentage of time in the proestrus, estrus, and metestrus phases (Figure 5B). PitIRKO DIO mice followed a pattern similar to WT and PitIRKO lean females.

Figure 5. Pituitary insulin receptor knockout rescues estrous cyclicity and ovulation on DIO background.

(A) Representative vaginal cytology plots from lean and diet induced obese (DIO) WT and PitIRKO mice. (B) Percent time spent in each stage of the estrous cycle by WT lean, WT DIO, and PitIRKO DIO animals. WT lean N=9, WT DIO N=25, PitIRKO DION=8. (C) Representative histological sections of ovaries taken from WT lean, WT DIO, and PitIRKO DIO mice. *=corpora lutea (D) Total corpora lutea (CL) counts from each group. WT lean N=13, PitIRKO lean N=4, WT DIO N=11, PitIRKO DIO N=7. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between WT DIO and WT lean/PitIRKO DIO: ** p-value less than 0.01, *** p-value less than 0.001.

Corpora lutea were quantified as a marker of recent ovulation. Histological sections of ovaries revealed a similar number of corpora lutea in WT lean and PitIRKO lean, with PitIRKO DIO mice showing an intermediate number of corpora lutea. Significantly fewer corpora lutea were found in WT DIO mice (Figure 5C and D) consistent with the persistent state of diestrus found in the WT DIO females.

Removal of Gonadotroph IR protects against infertility in DIO

Female mice were housed for 7 days with proven fertile males and four cycles of pairings were evaluated. The males were alternated between pairings with DIO and chow fed females in order to minimize any effects of diet on male reproductive function. Figure 6A shows a chart of successful mating events for five representative females for each group. The data for all mice are summarized in Figure 6B and demonstrate that WT lean and PitIRKO lean females exhibited fertility rates six times higher than WT DIO mice. As with numbers of corpora lutea (Figure 5D), PitIRKO DIO females had significantly improved fertility rates relative to WT DIO females (Figure 6B). For the litters that were born, the numbers of pups per litter and gestation periods were the same across groups (data not shown).

Figure 6. Pituitary insulin receptor knockout rescues infertility associated with diet induced obesity.

(A) Representative breeding study illustration: female mice were paired with four WT males for seven days and then returned to their own cages for three weeks to allow for birth of pups, indicating a successful pairing. Each row represents one individual female, and each bar represents one of her pairings. Five examples were chosen from each group in order to illustrate the fertility phenotypes. (B) Percent successful pairings for WT and PitIRKO groups under lean and DIO conditions. WT lean N=14, PitIRKO lean N=7, WT DIO N=13, PitIRKO DIO N=7. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Insulin stimulates an increase in circulating LH levels

To explore the acute response of the pituitary to insulin, circulating LH levels were measured before and after a peripheral injection of insulin. Forty minutes after insulin administration, serum LH levels increased by 58% in chow-fed mice and by 46.5% in WT DIO mice. Insulin administration did not increase LH levels in PitIRKO animals (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Preserved insulin sensitivity in WT DIO pituitary.

(A) Serum LH levels before and after mice were injected with insulin. WT lean N=10, PitIRKO lean N=12, WT DIO N=7, PitIRKO DIO N=11. (B) Signaling assay showing baseline and insulin-stimulated p-Akt in the pituitary, liver, and muscle. AU = Arbitrary Units. 3–5 animals were used in each group. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

The pituitary remains insulin sensitive under infertile, DIO conditions

Pituitary insulin responsiveness was assessed via insulin signaling assay. Mice were treated with insulin or saline after overnight fasting and harvested for liver, muscle, and pituitary tissue samples. Following insulin treatment, p-Akt levels increased in liver and muscle, as well as in pituitary tissue in WT lean mice (Figure 7B). WT DIO mice exhibited blunted phosphorylation of Akt in liver and muscle after insulin administration indicating peripheral insulin resistance. The WT DIO pituitary showed a significantly increased basal p-Akt level compared to WT lean, indicating preserved insulin sensitivity in the WT DIO pituitary to elevated insulin levels observed under basal conditions (Figure 7B). This sensitivity was lost in the PitIRKO DIO mice reflecting the lack of insulin receptor in the αGSU-expressing cells. After insulin administration, pituitary p-Akt levels were further increased in WT DIO mice, but no effect of insulin was observed in PitIRKO DIO mice. PitIRKO DIO liver and muscle displayed signaling profiles similar to WT DIO indicative of peripheral insulin resistance.

Discussion

The current rise in obesity and associated disorders such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and PCOS have drawn attention to the effect of these diseases on the reproductive system. Conditions marked by hyperinsulinemia are associated with infertility and abnormal regulation of LH secretion, yet the underlying mechanisms for these derangements remain unknown. To determine if insulin signaling at the pituitary gonadotroph plays a role in infertility related to obesity, we developed mice with the insulin receptor specifically deleted in the pituitary gonadotroph using the CRE/lox system. PitIRKO female mice on a regular chow diet displayed normal reproductive function, but in a model of diet-induced obesity, PitIRKO mice retained fertility while WT mice became infertile. This suggests that insulin receptor signaling in the pituitary is fundamental to the dysregulation of LH secretion associated with the obese state.

Evidence has pointed to both increased GnRH pulsatility and increased pituitary sensitivity to GnRH as a cause for the inappropriate gonadotropin secretion associated with PCOS (Hall et al., 1998), yet the mechanism underlying the increased pituitary sensitivity to GnRH in PCOS has not been fully elucidated. Some studies have shown that insulin enhances LH secretion and expression in vitro by augmenting GnRH action (Buggs et al., 2006; Soldani et al., 1994; Xia et al., 2001), implicating hyperinsulinemia and intensified gonadotropic insulin signaling as a cause for the increased LH levels observed in PCOS. Other studies performed in normal and obese PCOS women indicate that prolonged insulin infusion neither alters LH secretion (Patel et al., 2003), nor gonadotropin responses to GnRH (Mehta et al., 2005). It may be noted however that these studies involve isolated infusions of high concentrations of insulin, and these short-term supraphysiologic increases in insulin may regulate the reproductive axis differently than chronically elevated levels observed in states of insulin resistance.

In non-obese conditions, evidence for nutritional input to the reproductive axis has been well documented, but a specific role for insulin signaling in the pituitary has yet to be described. A pituitary-specific insulin receptor knockout was used to investigate the role of insulin signaling in the pituitary gonadotroph. When fed a standard low-fat diet, WT mice and PitIRKO mice exhibited similar fertility rates, estrous cyclicity, LH and FSH levels and corpora lutea counts, demonstrating that insulin receptor signaling in the pituitary is not required for normal reproductive function. While it is possible that insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) signaling may compensate for the IR impairment, the binding affinity of insulin for the IGF-1R is relatively low and the receptor is unlikely to be activated even at the elevated levels in obesity (Froesch et al., 1985; Simpson et al., 1998). However, both IGF-1R and IR signal through the insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins (Kim and Accili, 2002; Nakae et al., 2001) and IRS-2 knockout mouse are infertile with decreased serum LH levels (Burks et al., 2000) indicating that this common signaling pathway plays a role in regulating fertility under normal chow-fed conditions.

Having determined that lean WT and PitIRKO mice do not differ in the reproductive parameters assessed, mice were made obese to investigate the role of insulin signaling in the pituitary under hyperinsulinemic conditions. After three months on a high fat diet, WT DIO mice displayed the hallmarks of insulin resistance including fasting hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperleptinemia, consistent with the metabolic pattern seen in other mouse models of diet induced obesity (Batt and Mialhe 1966; Kleinridders et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2000; Taketomi et al., 1973; Tortoriello et al., 2004). WT DIO mice showed abnormal estrous cyclicity patterns (Figure 5A and B) and fewer ovulations (Figure 5C and D) mirrored by impaired breeding capacity (Figure 6) similar to PCOS women. The elevated baseline LH levels seen in the DIO model (Figure 4) are also similar to results in PCOS women where increased GnRH pulsatility and chronically elevated serum LH levels have been observed (Hall et al., 1998; Lawson et al., 2008; Marshall and Eagleson 1999; Rebar et al., 1976). WT DIO mice remained in persistent diestrus, and showed elevated LH serum and mRNA levels, which may be due to increased GnRH responsiveness of the pituitary gonadotroph (Figure 4E). The elevated LH levels may be the primary mediator of the infertility associated with the diet induced obese state as infertility in female mice with elevated levels of LH has previously been reported (Singh et al., 2009).

WT DIO mice also showed increased sensitivity to GnRH stimulation, similar to the increased LH responsiveness to GnRH that has been shown in PCOS women (Patel et al., 2003). The absence of increased sensitivity to GnRH in PitIRKO DIO mice implies a role for the insulin receptor in contributing to the increase in GnRH sensitivity. We propose that the pituitary remains insulin sensitive to chronically elevated insulin levels found in the DIO model, and modifies the pituitary response to GnRH in accordance with in vitro data showing insulin augmentation of GnRH in gonadotrophs (Adashi et al., 1981; Buggs et al, 2006; Soldani et al., 1995).

αGSU and LH-β mRNA levels were highest in WT DIO mice suggesting that elevated serum LH levels may be mediated by changes in transcriptional regulation of the LH subunit genes. Reduced LH subunit mRNA levels in the PitIRKO DIO mice compared to WT DIO mice implicate insulin signaling in this process as previously observed in vitro (Buggs et al., 2006). GnRH-R mRNA levels were increased in WT DIO compared to WT lean and PitIRKO DIO (Figure 4F). These data suggest that insulin may modulate GnRH-R levels to cause the increased LH secretion after GnRH stimulation found in DIO mice (Figure 4E). Whether the increase in LH subunit expression observed in the DIO mice is due primarily to the increased GnRH-R or whether insulin can directly regulate LH subunit expression cannot be clarified by these studies, but in vitro data suggests that insulin treatment alone cannot regulate LHβ expression (Buggs et al., 2006). Further investigation will elucidate the mechanism by which insulin regulates GnRH-R expression.

Obesity is known to produce insulin resistance in the classic target tissues of insulin action such as the liver and muscle (Biddinger and Kahn, 2006; Kitamura and Accili, 2004). However, whether the reproductive axis remains insulin sensitive in the setting of peripheral insulin resistance is controversial. To test the responsiveness of the pituitary to insulin stimulation in the absence or presence of obesity or in the absence or presence of the pituitary IR, mice were injected with insulin and acute LH responses were measured. WT lean mice showed an increase in serum LH following insulin injection, while PitIRKO mice, lacking the insulin receptor, did not show a response, indicating a direct role for insulin signaling in regulating LH secretion. WT DIO mice had higher baseline serum LH levels, but still showed an increase in insulin stimulated LH levels, suggesting that the pituitary gonadotroph is still sensitive in the obese state. Phospho-Akt, an intracellular marker of insulin action, was increased at baseline in the pituitaries of WT DIO mice prior to insulin treatment. After insulin treatment, the liver and muscle of DIO mice exhibited insulin resistance, as expected, with reduced activation of p-Akt compared to the response in the lean mice. The DIO pituitary exhibited higher basal p-Akt compared to lean mice likely reflecting the hyperinsulinemia of the DIO mice. After insulin stimulation, Akt phosphorylation in the pituitary increased to a similar level in lean and DIO mice, in contrast to the effect of insulin on Akt phosphorylation in the liver and muscle, which did not reach the same level in DIO mice compared to lean mice after insulin administration. This indicates enduring insulin sensitivity in the pituitary on the hyperinsulinemic background. The preserved insulin sensitivity seen in the WT DIO pituitary was lost in the PitIRKO DIO. In this model, IR knockout is targeted to αGSU expressing cells in the pituitary but does not target every cell type. PitIRKO DIO mice did not exhibit significantly increased phospho-Akt in response to insulin suggesting that the other cell types in the pituitary either do not express insulin receptor or that insulin signaling in other cell types does not activate Akt. A role for insulin regulation of the somatotroph has been proposed (Luque et al., 2006, Melmed et al., 1985) but the Akt response to insulin in these cells has not been investigated. As the effect of insulin is found to be inhibitory in the growth hormone axis, this may explain why p-Akt levels were not activated in other cell types.

Tissues specific differences in insulin sensitivity could be mediated at the level of the receptor, but a more likely locus would be tissue specific differences in IRS1 or 2 serine/threonine phosphorylation or proteasomal degradation (reviewed by White, 2006) as these are thought to underlie insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. Alternatively, the pituitary may not be sensitive to mechanisms causing insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. Perhaps the evolutionary history of insulin sensitivity in the reproductive axis has diverged from that in the metabolic tissues.

While fertility improved by deletion of the IR in the pituitary of DIO mice, it was not restored to normal. These data suggest that insulin signaling, or perhaps, another nutritional signal may act at another level in the reproductive axis to cause infertility associated with obesity. Dysregulation at the level of the ovary is suggested by the incomplete rescue of fertility and CL numbers in the PitIRKO DIO mice when compared to WT or PitIRKO lean mice despite serum LH levels and pituitary GnRH sensitivity that are indistinguishable in PitIRKO DIO mice when compared to WT or PitIRKO lean mice.

Insulin sensitivity in the ovary has been implicated in studies in which the ovary specifically responds to insulin (Poretski et al., 1987). In addition, insulin treatment of rat ovaries has been found to decrease follicle development in a time-dependent manner (Ozbilgin and Kuscu 2005). Others have found that the ovary becomes insulin resistant in PCOS patients (Wu et al., 2003). In addition to obesity, PCO is also found in women with Type A insulin resistance resulting from a mutation of the insulin receptor. Women with extreme insulin resistance due to mutations in the insulin receptor exhibit severe hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinism, similar to women with PCOS. These women have normal to low gonadotropins (Musso et al., 2005; Vambergue et al., 2006) in contrast to women with PCOS, implicating direct insulin signaling on the ovary contributing to the ovarian dysfunction. It is tempting to speculate that women with insulin receptor mutations are similar to our PitIRKO model, with normal LH levels in the setting of hyperinsulinemia and less robust response to GnRH stimulation than hyperinsulinemic controls. In contrast to our model, these women also lack insulin signaling in the brain and hypothalamus, which has been shown to regulate GnRH production using a brain-specific IR knockout mouse model (Bruning et al., 2000) and may contribute to the decrease in observed LH levels in these women. The degree of hyperandrogenemia is also higher in these women compared to our mouse model, which may be due to differences in central regulation of the reproductive axis.

A recent report by Nandi et al. demonstrated that insulin resistance in the absence of hyperglycemia did not result in elevated testosterone levels or drastic ovarian dysfunction in mice (Nandi et al., 2010). This paper further supports a model in which elevated insulin signaling in the pituitary, rather than insulin resistance, contributes to infertility.

Strain differences associated with diet induced obesity and infertility have been debated following the results of Tortoriello et al. who showed that one strain of DBA/2J mice became infertile after consuming a 35% fat by weight diet, while another strain of C57BL/6J mice displayed normal fertility. The C57BL/6J mice also gained significantly less weight than the DBA/2J mice, displaying resistance to the high-fat diet. Our studies involved a mixed background strain of CD1/129SvJ/C57Bl6 mice, which suggests that our results may reflect a fundamental property of dysregulation of reproductive function in obesity rather than strain-specific differences. While the mixed background model that we used may more closely resemble the DBA/2J mice described above, it is difficult to assess whether the higher percent fat chow we used (65%) would more generally induce obesity and infertility than the 35% used by Tortoriello et al.

In summary, these findings indicate a direct role for insulin signaling in the gonadotroph that is revealed in an obesity model of infertility. When WT mice became obese, they showed metabolic and reproductive profiles similar to women with hyperinsulinemia and fertility deficiencies such as PCOS. When the insulin receptor was ablated in the gonadotroph, obese PitIRKO mice displayed an improvement in reproductive function, implicating pituitary insulin signaling in the genesis of obesity-induced infertility.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Floxed-IR mice were designed with LoxP sites flanking exon 4 of the insulin receptor as previously described (Bruning et al., 2000). The αGSU transgenic mice have been previously described by our lab (Naik et al. 2006; Singh et al., 2009). All of the mice used in these experiments were maintained on a mixed CD1/129SvJ/C57Bl6 genetic background and each genotypic or dietary experimental group was compared to littermate controls carrying either the floxed IR gene without the αCre, the αCre without the floxed IR gene, or without either αCre or floxed IR. These littermate controls are referred to as “WT” mice throughout this manuscript. All procedures were performed with approval of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee under standard light and dark cycles. Prior to all experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Penn Veterinary Supply, Lancaster, PA) and blood samples were obtained via mandibular bleed or ocular bleed in the case of terminal studies.

Generation of Pituitary Specific Insulin Receptor (IR) knockout

Fl-IR mice were crossed with αGSU Cre mice in order to create a pituitary-specific insulin receptor knockout (PitIRKO). Genotyping primers for the presence of the floxed allele were P1: 5’-TGCACCCCATGTCTGGGACCC-3’ and P2: 5’-GCCTCCTGAATAGCTGAGACC-3’. Genotyping primers used to determine the presence of the Cre recombinase gene were CreF: 5’-ACGACCAAGTGACAGCAATGCTGT-3’ and CreR: 5’CGGTGCTAACCAGCGTTTTCGTTC-3’. The knockout allele was visualized via PCR reaction including three primers: P1, P2, and P3: 5’-TCTATCATGTGATCAATGATTC-3’ according to the strategy described by Kulkarni et al. (Kulkarni et al., 1999). Primers P1 and P2 were designed to produce a 320 bp band to indicate the floxed-IR alleles in tissue DNA samples taken from liver, muscle, hypothalamus, ovary, and pituitary. Primers P2 and P3 were designed to produce a 220 bp band following excision of the sequence between the LoxP sites.

Generation of Diet Induced Obesity

Mice were placed on a high fat diet starting at 8 weeks of age, and maintained on the diet for 12 weeks prior to study and throughout the course of study. The high fat diet consisted of 20% Kcal from protein, 20% Kcal from carbohydrate, and 60% Kcal from fat with an energy density of 5.24 kcal/gm (Research Diets, Inc New Brunswick, NJ). Wood chip bedding was maintained in these cages so that mice would not supplement their diet by eating the standard corncob bedding. Mice were weighed every 2 weeks along with a lean cohort of control littermates maintained on a regular chow diet. The regular chow diet (Tekland Global 18% protein diet) was 24% Kcal from protein, 58% Kcal from carbohydrate, and 18% Kcal from fat with an energy density of 3.1kcal/g (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN).

After the 12 weeks of high fat diet (HFD), mice were assessed for fasting glucose, insulin, and leptin levels. Glucose was measured using a Glucometer Elite glucometer while serum insulin and leptin were measured on the Luminex 200IS system using the Milliplex Map Mouse Serum Adipokine Panel (Millipore, Billerica, MA) (see hormone assays below).

Estrous Cycle Analysis

Vaginal cytology was assessed daily between 9 and 10 am for ten consecutive days, and then analyzed for percent time spent in each stage. Vaginal cells were collected via saline lavage and then fixed with methanol and stained with the DIFF Quick Stain Kit (IMEB Inc., San Marcos, CA). Stages were assessed based on vaginal cytology (Nelson et al., 1982): predominant cornified epithelium indicated the estrus stage, predominant nucleated cells indicated the proestrus stage, both cornified and leukocytes indicated the metestrus stage, and predominant leukocytes indicated the diestrus stage.

Hormone Assays

To measure serum levels of LH, FSH, insulin, and leptin, serum samples were collected from mice via mandibular bleed. Samples were obtained between 9:00 and 10:00 am for baseline LH and FSH, GnRH stimulation and insulin stimulation tests so as to avoid cycle dependent LH surges that occur in the late afternoon on the evening of proestrus. Rodent morning LH levels are not thought to vary in a cycle dependent manner (Halena et al., 2006). For fasting measurements of insulin, leptin and glucose, samples were also obtained between 9:00 and 10:00 am. Serum was analyzed on a Luminex 200IS platform using the Milliplex Map Rat Pituitary Panel. Serum samples from individual mice were analyzed in duplicate. A standard curve was generated using 5-fold serial dilutions of the hormone reference provided by Millipore. Low and high quality controls were also run on each assay to assess CV values. The assay detection limit for LH was 0.048ng/mL; for FSH, 0.032ng/mL; for insulin, 18.5pM; and for leptin, 6.2pM. Serum Testosterone was measured by radioimmunoassay at the University of Virginia Ligand Assay Core.

GnRH stimulation

Blood was collected from mice via mandibular bleed prior to subcutaneous injection of 100ng/kg GnRH (Sigma L7134 Luteinizing hormone releasing hormone human acetate salt). Ten minutes after injection, blood was collected again from the other cheek. Fold-change in serum LH was assessed.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from pituitary tissue using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). PCR reactions were performed with IQ SYBRGreen Supermix (BioRad) and fluorescence was measured using the MyiQ quantitative real-time thermocycler (BioRad). The following primer sets were used: LHβ (sense 5’-CAGTCTGCATCACCTTCACCA-3’ and antisense 5’-GGTAGGTGCACACTGGCTGA-3’), αGSU (sense 5’-GTGTATGGGCTGTTGCTTCTCC-3’ and antisense 5’-GCACTCCGTATGATTCTCCACTCTG-3’), GnRH-R (sense 5’-CAGCTTTCATGATGGTGGTG-3’ and antisense 5’-TAGCGAATGCGACTGTCATC-3’), GAPDH (sense 5’-GGGCATCTTGGGCTACACT-3’ and antisense 5’-GGCATCGAAGGTGGAAGAGT-3’), and ribosomal 18S (sense 5’-GCATGGCCGTTCTTAGTTGG-3’ and antisense 5’-TGCCAGAGTCTCGTTCGTTA-3’). Each reaction was run in triplicate and for each assay a standard curve was created using 10-fold serial dilutions of cDNA. All experiments had efficiencies between 95% and 105% and displayed normal melt curves. Fold changes in relative gene expression were calculated by 2−Δ(ΔCt) where ΔCt = Ct (gene of interest) - Ct (18S) and Δ(ΔCt) = ΔCt (PitIRKO, WT DIO, or PitIRKO DIO gene of interest) - mean ΔCt (WT Lean gene of interest). Results are expressed as fold differences in relative gene expression with respect to WT Lean.

Ovarian Histology

Ovaries were collected from mice and placed immediately in 10% formalin. 5μm sections of ovarian tissue were obtained every 100μm throughout the length of the ovary. Ovaries were stained with H and E by the Johns Hopkins Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology Phenotyping Core. The total number of corpora lutea counted per mouse were compared across groups.

Breeding studies

Female mice were entered into a breeding rotation with 4 proven fertile WT lean males. Each female spent 7 days in a cage with a male, and then was removed for 28 days to allow for determination of pregnancy. Pregnancy was assessed by the generation of litters during that 28-day period. Once the 28 days were up, that female was moved into a cage with the next male. This way, each female was rotated through all 4 males, and had the same amount of time (7 days) in which to attempt pregnancy. Vaginal plugs were usually observed in obese animals indicating that the infertility was unlikely to be due to a mechanical defect. Based on the number of successful pregnancies resulting from the four mating attempts, a fertility rate was calculated for each individual female. These fertility rates, or % successful matings, were then compared across groups.

Insulin stimulation

Blood was collected from mice via mandibular bleed prior to subcutaneous injection of 1.5Units/Kg regular insulin (Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) and forty minutes following injection. An injection of 20% glucose weight/volume was also administered at the same time as the insulin and glucose levels were monitored throughout the experiment to confirm that the glucose administration was sufficient to prevent the mice from becoming hypoglycemic.

Insulin Signaling Assay

WT lean, WT DIO, PitIRKO lean, and PitIRKO DIO mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with 1.5 Unit/Kg body weight insulin or 0.9% saline. Mice were sacrificed after 10 minutes for pituitary, liver, and muscle tissue collection. Tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized in 1× Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) supplemented with Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche Diagnostics). Protein concentration was quantified by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). To quantify levels of phospho-Akt/PKB (Ser473), 10 μg protein from each tissue was analyzed with the Cell Signaling Buffer and Detection MilliplexTM Map Kit with assay buffer 2 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Luminex200 (Austin, Texas) system. Analysis was performed using the XPonent 3.0 software program. Total MEK was also measured in the same well as an internal loading control. Values were assessed as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of phospho-specific signal.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± standard error. Significance was determined via one- or two-way ANOVA with the appropriate post-hoc tests if significant variations were observed across groups. The graphs and analyses were constructed using the GraphPad Prism 4 program (La Jolla, CA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH RO1HD044608 granted to A.W. along with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH through cooperative agreement (U54 HD58820 granted to A.W., F.E.W. and S.R.) as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research. Serum levels measured on the Luminex platform were done with support from the DRTC Integrated Physiology Core at Johns Hopkins. Support was also received from NIH R01 DK33201 to C.R.K. Serum Testosterone levels were measured by the University of Virginia as part of NICHD (SCCPIR) Grant U54-HD28934, University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adashi EY, Hsueh AJ, Yen SS. Insulin enhancement of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone release by cultured pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1981;108:1441–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-4-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt R, Mialhe P. Insulin resistance of the inherently obese mouse--obob. Nature. 1966;212:289–90. doi: 10.1038/212289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddinger SB, Kahn CR. From mice to men: insights into the insulin resistance syndromes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:123–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.124723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, Klein R, Krone W, Muller-Wieland D, Kahn CR. Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science. 2000;289:2122–5. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggs C, Weinberg F, Kim E, Wolfe A, Radovick S, Wondisford F. Insulin augments GnRH-stimulated LHbeta gene expression by Egr-1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;249:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks DJ, Font de Mora J, Schubert M, Withers DJ, Myers MG, Towery HH, Altamuro SL, Flint CL, White MF. IRS-2 pathways integrate female reproduction and energy homeostasis. Nature. 2000;407:377–82. doi: 10.1038/35030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JL, Nosbisch C. Suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and testosterone secretion during short term food restriction in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Endocrinology. 1991;128:1532–40. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froesch ER, Zapf J. Insulin-like growth factors and insulin: comparative aspects. Diabetologia. 1985;28:485–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00281982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halena CV, de Oliveira Poletini M, Sanvitto GL, Hayashi S, Franci CR, Anselmo- Franci JA. Changes in alpha-estradiol receptor and progesterone receptor expression in the locus coeruleus and preoptic area throughout the rat estrous cycle. J Endocrinol. 2006;188:155–65. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Taylor AE, Hayes FJ, Crowley WFJ. Insights into hypothalamic pituitary dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21:602–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03350785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Accili D. Signalling through IGF-I and insulin receptors: where is the specificity? Growth Horm IGF Res. 2002;12:84–90. doi: 10.1054/ghir.2002.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y, Accili D. New insights into the integrated physiology of insulin action. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2004;5:143–149. doi: 10.1023/B:REMD.0000021436.91347.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinridders A, Schenten D, Konner AC, Belgardt BF, Mauer J, Okamura T, Wunderlich FT, Medzhitov R, Bruning JC. MyD88 signaling in the CNS is required for development of fatty acid-induced leptin resistance and diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2009;10:249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni RN, Bruning JC, Winnay JN, Postic C, Magnuson MA, Kahn CR. Tissue-specific knockout of the insulin receptor in pancreatic beta cells creates an insulin secretory defect similar to that in type 2 diabetes. Cell. 1999;96:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Jain S, Sun S, Patel K, Malcolm PJ, Chang RJ. Evidence for insulin suppression of baseline luteinizing hormone in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome and normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2089–96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Thomas TC, Storlien LH, Huang XF. Development of high fat diet-induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57Bl/6J mice. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:639–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque RM, Kineman RD. Impact of obesity on the growth hormone axis: evidence for a direct inhibitory effect of hyperinsulinemia on pituitary function. Endocrinol. 2006;147:2754–2763. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC, Eagleson CA. Neuroendocrine aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28:295–324. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RV, Patel KS, Coffler MS, Dahan MH, Yoo RY, Archer JS, Malcom PJ, Chang RJ. Luteinizing hormone secretion is not influenced by insulin infusion in women with polycystic ovary syndrome despite improved insulin sensitivity during pioglitazone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2136–41. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melmed S, Neilson L, Slanina S. Insulin suppresses rat growth hormone messenger ribonucleic acid levels in rat pituitary tumor cells. Diabetes. 1985;34:409–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso C, Shawker T, Cochran E, Javor ED, Young J, Gorden P. Clinical evidence that hyperinsulinaemia independent of gonadotropins stimulates ovarian growth. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik K, Pittman I4, Wolfe A, Miller RS, Radovick S, Wondisford FE. A novel technique for temporally regulated cell type-specific Cre expression and recombination in the pituitary gonadotroph. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37:63–9. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D. Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:818–35. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Wang X, Accili D, Wolgemuth DJ. The effect of insulin signaling on female reproductive function independent of adiposity and hyperglycemia. Endocrinol. 2010 Feb 22; doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0788. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratil AM, Song H, Hernandez JB, Cherrington BD, Santos SJ, Low JM, Do MH, Lawson MA. Insulin augments gonadotropin-releasing hormone induction of translation in LbetaT2 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;311:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JF, Felicio LS, Randall PK, Sims C, Finch CE. A longitudinal study of estrous cyclicity in aging C57BL/6J mice: I. Cycle frequency, length and vaginal cytology. Biol Reprod. 1982;27:327–339. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod27.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbilgin K, Kuscu NK. Two oestrous cycles. Ten days insulin treatment reduced ovarian leptin expression of rat. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:923–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K, Coffler MS, Dahan MH, Yoo RY, Lawson MA, Malcom PJ, Chang RJ. Increased luteinizing hormone secretion in women with polycystic ovary syndrome is unaltered by prolonged insulin infusion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5456–5461. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poretsky L, Kalin MF. The gonadotropic function of insulin. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:132–141. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-2-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebar R, Judd HL, Yen SS, Rakoff J, Vandenberg G, Naftolin F. Characterization of the inappropriate gonadotropin secretion in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:1320–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI108400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage JJ, Mullen RD, Sloop KW, Colvin SC, Camper SA, Franklin CL, Rhodes SJ. Transgenic mice expressing LHX3 transcription factor isoforms in the pituitary: effects on the gonadotrope axis and sex-specific reproductive disease. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:105–17. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HL, Umpleby AM, Russell-Jones DL. Insulin-like growth factor-I and diabetes. A review. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1998;8:83–95. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(98)80098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Wolfe A, Ng Y, Divall SA, Buggs C, Levine JE, Wondisford FE, Radovick S. Impaired Estrogen Feedback and Infertility in Female Mice with Pituitary-Specific Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ESR1) Biol Reprod. 2009;81:488–496. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldani R, Cagnacci A, Paoletti AM, Yen SS, Melis GB. Modulation of anterior pituitary luteinizing hormone response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone by insulin-like growth factor I in vitro. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:634–7. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldani R, Cagnacci A, Yen SS. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-II enhance basal and gonadotrophin-releasing hormone-stimulated luteinizing hormone release from rat anterior pituitary cells in vitro. Eur J Endocrinology. 1994;131:641–645. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1310641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketomi S, Tsuda M, Matsuo T, Iwatsuka H, Suzuoki Z. Alterations of hepatic enzyme activities in KK and yellow KK mice with various diabetic states. Horm Metab Res. 1973;5:333–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1093938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoriello DV, McMinn J, Chua SC. Dietary-induced obesity and hypothalamic infertility in female DBA/2J mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1238–47. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vambergue A, Lautier C, Valat AS, Cortet-Rudelli C, Grigorescu F, Dewailly D. Follow-up study to two sisters with type A syndrome of severe insulin resistance gives a new insight into PCOS pathogenesis in relation to puberty and pregnancy outcome: a case report. Hu Reprod. 2006;21:1274–1278. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MF. Regulating insulin signaling and beta-cell function through IRS proteins. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:725–37. doi: 10.1139/y06-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XK, Zhou SY, Liu JX, Pollanen P, Sallinen K, Makinen M, Erkkola R. Selective ovary resistance to insulin signaling in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:954–65. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia YX, Weiss JM, Polack S, Diedrich K, Ortmann O. Interactions of insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin and estradiol with GnRH-stimulated luteinizing hormone release from female rat gonadotrophs. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;144:73–79. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]