Abstract

Leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) mutations are a common cause of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Here, we identify inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase, which are protective in in vitro and in vivo models of LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration. These results establish that LRRK2-induced degeneration of neurons in vivo is kinase dependent and that LRRK2 kinase inhibition provides a potential new neuroprotective paradigm for the treatment of PD.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a very common neurodegenerative disorder with no proven neuroprotective or neurorestorative therapies. Recent advances in identifying genetic causes of PD have provided new opportunities for discovery of therapeutic targets and agents to potentially prevent the degenerative process of PD. Patients with LRRK2 mutations are clinically and neurochemically indistinguishable from idiopathic PD1. Disease segregating mutations in LRRK2 lead to neurotoxicity in vitro 2–4 and loss of dopamine neurons in PD patients 5. LRRK2 toxicity in vitro is linked to kinase activity and GTP binding, since mutations in LRRK2 that interfere with kinase activity and GTP binding, inhibit toxicity. Whether LRRK2 toxicity requires kinase activity in vivo and whether pharmacologic inhibition could protect against LRRK2 toxicity is not known.

To identify LRRK2 inhibitors, LRRK2 autophosphorylation (Fig. 1) and LRRK2-mediated phosphorylation of myelin basic protein (MBP) (Supplementary Fig. 1) were monitored in the presence or absence of 84 Biomol kinase and phosphatase inhibitors at 16 μM (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1). Indolinone compounds including staurosporine (compound 6), GF 109203X (compound 31), Ro 31- 8220 (compound 33), 5-iodotubercidin (compound 49), GW5074 (compound 56), and indirubin-3′-monooxime (compound 70) and anthracene compounds, SP 600125 (compound 68), damnacanthal (compound 22) substantially inhibit LRRK2 autophosphorylation (Fig. 1a, b) or LRRK2-mediated phosphorylation of MBP (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). None of the inhibitors significantly enhanced LRRK2 kinase activity.

Figure 1.

Identification of inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase. (a) LRRK2 autophosphorylation (% of control) ± Biomol inhibitors (See Table S1). Red indicates LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. ***p<0.001 by ANOVA compared to the other groups. Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 34 (total) and F = 18.4144. (b) Representative phosphoimage of WT and LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. LRRK2 kinase dead (D1994A) and KN-93 are negative controls. (c, d) LRRK2 kinase inhibitors dose-response curves of LRRK2 WT and G2019S autophosphorylation. (e, f, g) Raf kinase inhibitors dose-response curves on LRRK2 WT, LRRK2 G2019S and LRRK1 autophosphorylation. (h) LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. LRRK2 G2019S kinase dead mutant (G2019S, D1994A), ZM336372 and indirubin are negative controls. (i) Quantification of LRRK2 G2019S autophophorylation and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. ***P < 0.001, by ANOVA, Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Degree of freedom for LRRK2 = 17 (total) and F = 22.401. Degree of freedom for 4E-BP1 = 17 (total) and F = 22.453. All data represents the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments.

The IC50’s of the 8 inhibitors were determined against autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation by wild type (WT) and G2019S LRRK2 (Fig. 1c, d, Supplementary Fig. 1 c, d and Supplementary Table 2). All the inhibitors except indirubin-3′-monooxime have relatively similar potency against WT and G2019S LRRK2 autophosphoryation activity (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Table 2). Indirubin-3′-monooxime more potently inhibits LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation. Staurosporine, damnacanthal, SP 600125, 5-iodotubercidin equivalently inhibit both WT and LRRK2 G2019S MBP phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 1 c, d and Supplementary Table 2). Both PKC inhibitors, Ro 31-8220 and GF109203X more potently inhibit both WT and G2019S LRRK2 MBP phosphorylation. GW5074 is less potent in inhibiting both WT and G2019S LRRK2 MBP phosphorylation. All 8 inhibitors have a similar inhibitory profile against LRRK1 autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 2a d).

Since LRRK2 and LRRK1 are related to the MAP kinase kinase kinase, Raf 6 and GW5074 inhibits Raf kinase 7, LRRK2 and LRRK1 autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation were monitored in the presence or absence of additional Raf kinase inhibitors, ZM336372, Sorafenib and Raf inhibitor IV (Fig. 1e). GW5074 more potently inhibits LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation than LRRK1 autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation (Fig. 1f, g and Supplementary Fig. 1e, f, 2e and Supplementary Table 3). ZM336372 has minimal to no effect on LRRK1 autophophorylation and MBP phosphorylation and no effect on WT or G2019S LRRK2 autophosphorylation or MBP phosphorylation. Both Sorafenib and Raf inhibitor IV inhibit LRRK2 autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation MBP with less potency than GW5074, but they have minimal to no effect on LRRK1 autophosphorylation or MBP phosphorylation (Fig. 1e, f, g and Supplementary Fig. 1e, f, 2e and Supplementary Table 3). These results taken together indicate that GW5074 inhibits both LRRK2 and LRRK1 kinase activities, whereas Sorafenib and Raf inhibitor IV are relatively selective for LRRK2 kinase activity and ZM336372 has minimal to no effect on both LRRK2 and LRRK1 kinase activities.

Indirubin-3′-monooxime and the related analog, indirubin were also compared against LRRK1 WT, LRRK2 WT and LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation or MBP phosphorylation. Indirubin-3′-monooxime inhibits LRRK1 WT, LRRK2 WT and LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation, whereas indirubin has no effect on LRRK1 WT, LRRK2 WT and LRRK2 G2019S autophosphorylation or MBP phosphorylation (Supplementary Table 3). GW5074 and indirubin-3′-monooxime also inhibit LRRK2-mediated eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein (4E-BP1), a putative physiologic LRRK2 substrate8, whereas ZM336372 and indirubin do not inhibit LRRK2 phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 (Fig. 1h, i).

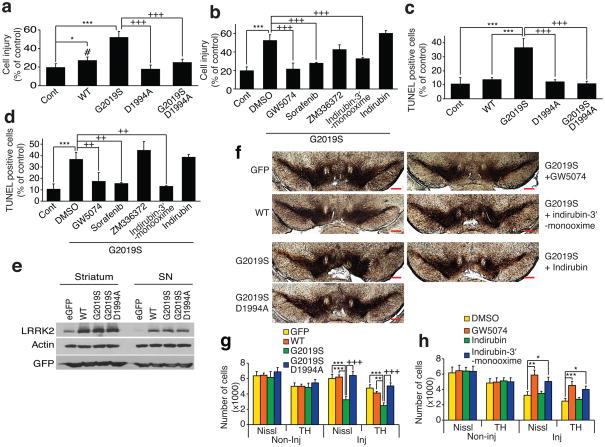

Both LRRK2 WT and LRRK2 G2019S overexpression leads to primary cortical neuron injury as assessed by neurite shortening (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3) and LRRK2 G2019S overexpression leads to cell death as assessed by DNA fragmentation (TdT-mediated X-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay) (Supplementary Methods) (Fig. 2c, d), whereas a kinase dead versions of LRRK2 WT (D1994A) and LRRK2 G2019S (G2019S, D1994) are devoid of toxicity as previously described 3,4,9 (Fig. 2a, d and Supplementary Fig. 3). Treatment of the cortical cultures with 0.5 μM GW5074 and 0.5 μM indirubin-3′-monooxime, which inhibit both LRRK2 and LRRK1, attenuate LRRK2 G2019S cell injury and cell death (Fig. 2b, d). The Raf kinase inhibitor, Sorafenib (0.5 μM), which is relatively selective for LRRK2 (see Supplementary Table 3), also completely protects against LRRK2 G2019S toxicity (Fig. 2b, d and Supplementary Fig. 3). The Raf kinase inhibitor, ZM336372 (0.5 μM), which does not inhibit either LRRK2 or LRRK1 kinase activity fails to inhibit LRRK2 G2019S toxicity (Fig. 2b, d and Supplementary Fig. 3). The cyclin-dependent kinase and GSK-3β inhibitor, indirubin, which does not inhibit either LRRK2 or LRRK1 kinase activity fails to inhibit LRRK2 G2019S toxicity (Fig. 2b, d and Supplementary Fig. 3). These results taken together indicate that the protection afforded by the Raf inhibitors (GW5074 and Sorafenib) and the cyclin-dependent kinase and GSK-3β inhibitor, indirubin-3′-monooxime, are due to inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity and not inhibition of Raf, cyclin-dependent or GSK-3β kinase activity, respectively.

Figure 2.

LRRK2 kinase inhibition protects against LRRK2-induced neuronal toxicity. (a) Quantification of neuronal injury, normalized to number of viable neurons transfected with eGFP in three experiments. ***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05 by ANOVA compared to eGFP control. +++P < 0.001 by ANOVA compared to LRRK2 G2019S. #P < 0.05 by ANOVA compared to LRRK2 D1994A. Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 21 (total) and F = 42.436. (b) Quantification of neuronal injury ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. ***P < 0.001 by ANOVA compared to eGFP control. +++P < 0.01 by ANOVA compared to DMSO control. Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 28 (total) and F = 47.3152. (c) Quantification of neuronal cell death via TUNEL. ***P< 0.001 by ANOVA compared to eGFP control. +++P< 0.01 by ANOVA compared to LRRK2 G2019S. Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 14 (total) and F = 12.4378. (d) TUNEL quantification ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. **P< 0.01 by ANOVA compared to eGFP control. ++P< 0.01 by ANOVA compared to DMSO control. Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 20 (total) and F = 16.6113. (e) LRRK2 and GFP immunoblots of striatum and substantia nigra (SN) 2 weeks after intrastriatal infusion of HSVPrPUC/CMVeGFP, LRRK2 WT (HSV-LRRK2 WT/CMVeGFP) and LRRK2 G2019S (HSV-LRRK2 G2019S/CMVeGFP). (f) SN tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunolabeling 3 weeks after HSV-mediated delivery of eGFP, LRRK2 WT, LRRK2 G2019S, or LRRK2 G2019S, D1994A ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. Scale bar = 500 μm. (g) TH-positive and Nissl-positive cell counts comparing eGFP, LRRK2 WT, LRRK2 G2019S, or LRRK2 G2019S, D1994A. Each bar represents the mean number (± S.E.M., n = 8) of TH-positive cells. ***P< 0.001 by ANOVA compared to eGFP control and LRRK2 WT. +++P< 0.001 by ANOVA compared to LRRK2 G2019S, D1994A. Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 67 (total) and F = 6.5115 for Nissl staining groups. Degree of freedom = 68 (total) and F = 7.1292 for TH staining groups. (h) TH- positive and Nissl-positive cell counts comparing LRRK2 G2019S ± LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. Each bar represents the mean number (± S.E.M., n = 8) of TH-positive cells. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, and ***P< 0.001 by ANOVA compared to DMSO vehicle control. Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. Degree of freedom = 70 (total) and F = 5.6004 for Nissl staining groups. Degree of freedom = 88 (total) and F = 5.0678 for TH staining groups. All procedures used in this study involving animals were approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute Animal Care Committee and by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

To determine the efficacy of the LRRK2 kinase inhibitors in vivo, a herpes simplex virus (HSV) amplicon-based mouse model of LRRK2 DA neurotoxicity was developed (Supplementary Methods) (Fig. 2e, h). GFP is extensively co-expressed with TH and in ~75 % of substantia nigra compacta neurons after an intrastriatal HSVPrPUC/CMVeGFP injection (Supplementary Fig. 4). Immunoblot analysis confirms that WT, G2019S and G2019S, D1994A LRRK2 are overexpressed at equivalent levels (Fig. 2e). HSV amplicon-mediated delivery of LRRK2 G2019S induces significant loss of TH-positive neurons 3 weeks after stereotaxic injection into the ipsilateral striatum of mice compared to LRRK2 WT and eGFP control viruses (Fig. 2f, g). HSV amplicon-mediated delivery of LRRK2 G2019S, D1994A causes no neuronal loss similar to LRRK2 WT and GFP control viruses (Fig. 2f, g). Since GW5074 and indirubin-3′-monooxime and indirubin are known to cross the blood brain barrier 7,10,11, they were chosen to test whether inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity is protective in vivo. Twice daily injections of the LRRK2 kinase inhibitors, GW5074 and indirubin-3′-monooxime, (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) attenuate the loss of TH-positive neurons induced by HSV-LRRK2 G2019S/CMVeGFP compared to DMSO and indirubin injected controls (Fig. 2f, h). The density of TH-positive fibers is also reduced in HSV-LRRK2 G2019S compared to HSV-eGFP control and HSV-LRRK2 WT and the reduction in the density of TH-positive fibers is rescued by GW5074 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Transduction of eGFP and LRRK2 WT do not show any signs of inflammation as determined by isolectin B4 (ILB4-positive cells), but LRRK2 G2019S induces a significant increase of ILB4-positive cells in the striatum and SNc, which is also prevented by administration of GW5074 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The major finding of this paper is the identification of kinase inhibitors that inhibit LRRK2 kinase activity and protect against LRRK2 toxicity both in vitro and in vivo. Other kinase inhibitors have recently been reported to inhibit LRRK2 kinase activity with similar potency to those described here 12–15. Since an authentic substrate of LRRK2 has yet to be identified, there should be a note of caution regarding the physiological relevance of the screens used in this and related studies based on autophosphorylation and artificial substrates. These results hold particular promise for further studies focused on developing selective and potent inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase activity. Moreover, they demonstrate that pharmacologic inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity is a potentially promising therapeutic modality for the treatment of neurodegeneration in PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Burris and L. Lotta for helper virus-free amplicon packaging. Drs. C. Cook, K. Kehoe, J. Dunmore and C. Eckman provided technical support for some of the in vivo HSV studies. We also thank Drs. G. and K. Caldwell and S. Hamamichifor helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Heath, P50NS38377, R01ES014470 (KMZ), R01-AG023593 (WJB), R00-NS058111 (ABW), NS36420 (HF) and Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, DAMD17-02-1-0695 (HF), the Mayo Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. TMD is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BDL, JV, LP, ABW, VLD, and TMD designed the experiments. BDL, JV, HSK, YIL, and JHS generated data. KAM, WJB, and HF generated HSV LRRK2s. BDL and JV analyzed data. BDL, VLD, and TMD wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

TMD is a paid consultant to Merck KGAA. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Medicine website

References

- 1.Gasser T. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greggio E, et al. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith WW, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1231–1233. doi: 10.1038/nn1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West AB, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whaley NR, Uitti RJ, Dickson DW, Farrer MJ, Wszolek ZK. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006:221–229. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mata IF, Wedemeyer WJ, Farrer MJ, Taylor JP, Gallo KA. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin PC, et al. J Neurochem. 2004;90:595–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai Y, et al. EMBO J. 2008;27:2432–2443. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith WW, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18676–18681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508052102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leclerc S, et al. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:251–260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W, et al. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1678–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand VS, et al. FEBS J. 2009;276:466–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covy JP, Giasson BI. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols RJ, et al. Biochem J. 2009;424:47–60. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichling LJ, Riddle SM. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.