Abstract

The quinone/semiquinone/hydroquinone triad (Q/SQ•−/H2Q) represents a class of compounds that has great importance in a wide range of biological processes. The half-cell reduction potentials of these redox couples in aqueous solutions at neutral pH, E°′, provide a window to understanding the thermodynamic and kinetic characteristics of this triad and their associated chemistry and biochemistry in vivo. Substituents on the quinone ring can significantly influence the electron density “on the ring” and thus modify E°′ dramatically. E°′ of the quinone governs the reaction of semiquinone with dioxygen to form superoxide. At near-neutral pH the pKa's of the hydroquinone are outstanding indicators of the electron density in the aromatic ring of the members of these triads (electrophilicity) and thus are excellent tools to predict half-cell reduction potentials for both the one-electron and two-electron couples, which in turn allow estimates of rate constants for the reactions of these triads. For example, the higher the pKa's of H2Q, the lower the reduction potentials and the higher the rate constants for the reaction of SQ•− with dioxygen to form superoxide. However, hydroquinone autoxidation is controlled by the concentration of di-ionized hydroquinone; thus, the lower the pKa's the less stable H2Q to autoxidation. Catalysts, e.g., metals and quinone, can accelerate oxidation processes; by removing superoxide and increasing the rate of formation of quinone, superoxide dismutase can accelerate oxidation of hydroquinones and thereby increase the flux of hydrogen peroxide. The principal reactions of quinones are with nucleophiles via Michael addition, for example, with thiols and amines. The rate constants for these addition reactions are also related to E°′. Thus, pKa's of a hydroquinone and E°′ are central to the chemistry of these triads.

Keywords: Semiquinone, Free radical, Reduction potentials, Thermodynamics

Introduction

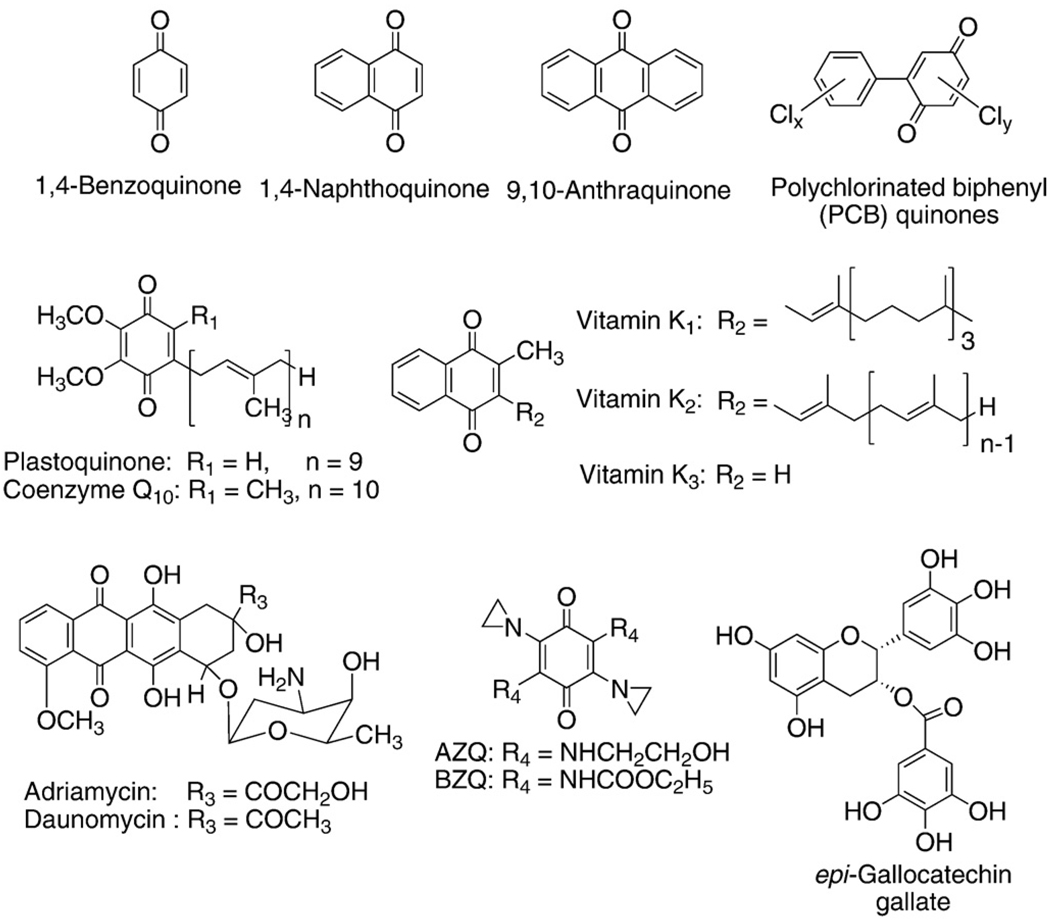

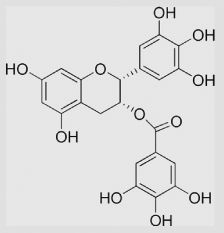

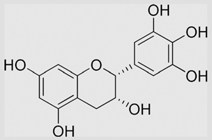

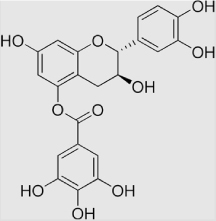

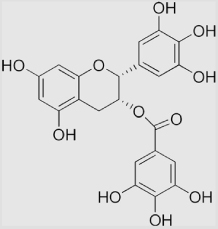

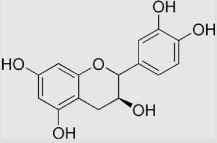

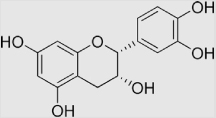

Mass spectrometry of interstellar dust observed onboard the NASA spacecraft STARDUST has found quinones to be the principal class of compounds in the dust, indicating they are among the oldest organic molecules in the universe [1]. The quinone/semiquinone/hydroquinone (Q/SQ•−/H2Q) triad is an important component of many redox systems in biology (Fig. 1). This moiety is a common constituent of many biologically relevant molecules, serving as a vital link in the movement of electrons through cells and tissues; the moiety can also be at the root of pathology, as in the case of many xenobiotics (Fig. 2). Coenzyme Q (ubiquinone) serves as a key agent for electron and proton transfer in mitochondria [2,3], while plastoquinone serves a similar function in photosynthesis [4]. The quinone moiety is also a key functional group in vitamin K. Quinones/hydroquinones are moieties central in the mechanisms of action of many xenobiotics, ranging from drugs such as adriamycin [5–7], to phytochemicals that have health benefits, such as epigallocatechin gallate [8–10].

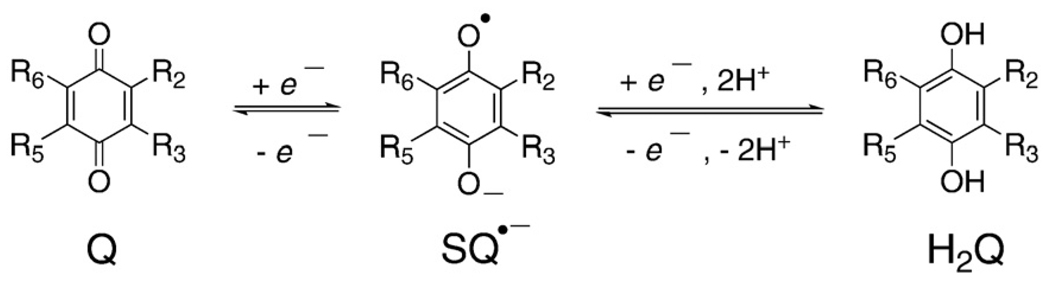

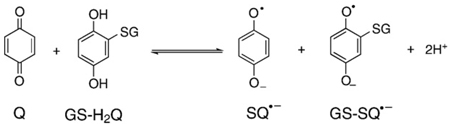

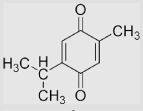

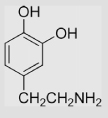

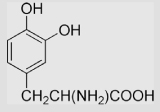

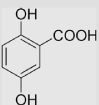

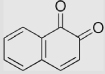

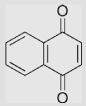

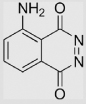

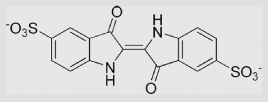

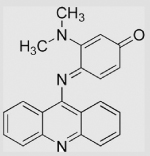

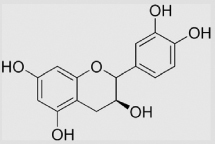

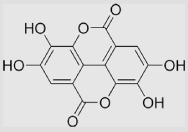

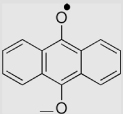

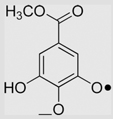

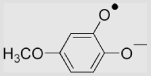

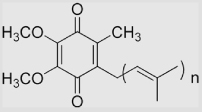

Fig. 1.

Shown are the basic structures of quinones, semiquinones, and corresponding hydroquinones. We show here the dominant species of each component of the triad that would be present in aqueous solution at pH 7. For example, for 1,4-hydroquinone the pKa's are 9.8 and 11.4 for the first and second protons of the phenoxyl moieties, respectively [11,12]. The pKa of the protonated 1,4-semiquinone radical (SQH•) is 4.1 [13,14]; thus, it is shown as the radical anion.

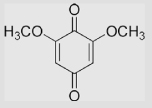

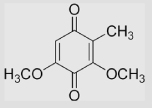

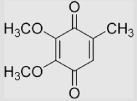

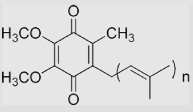

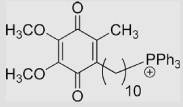

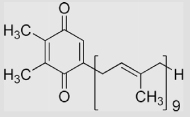

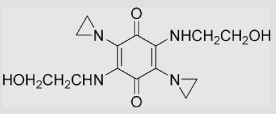

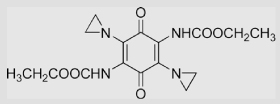

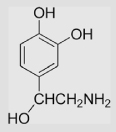

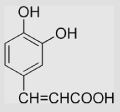

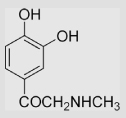

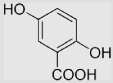

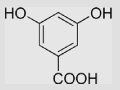

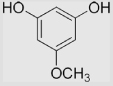

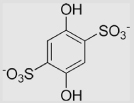

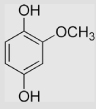

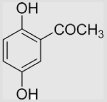

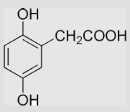

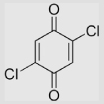

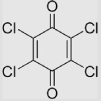

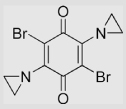

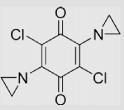

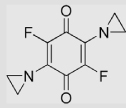

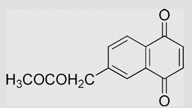

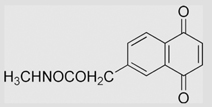

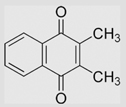

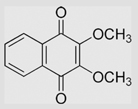

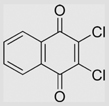

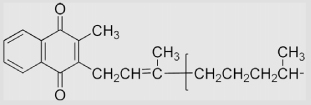

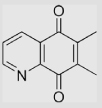

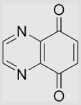

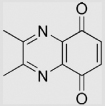

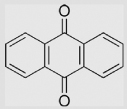

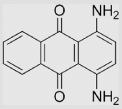

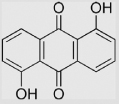

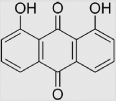

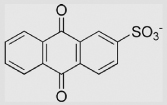

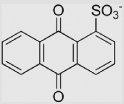

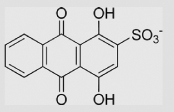

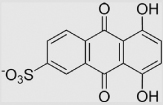

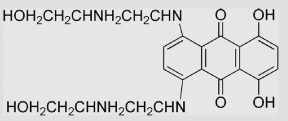

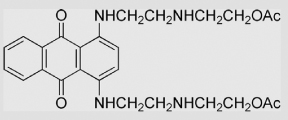

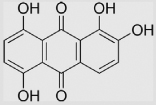

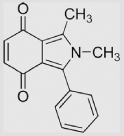

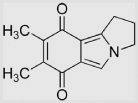

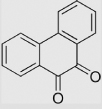

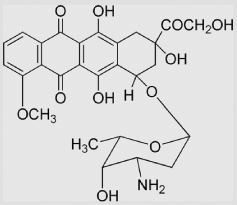

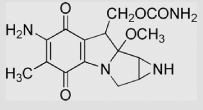

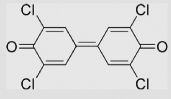

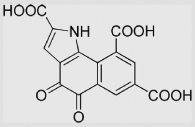

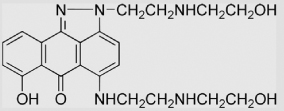

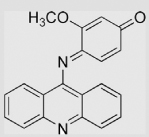

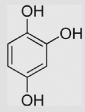

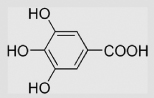

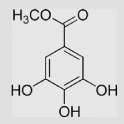

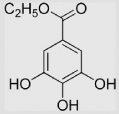

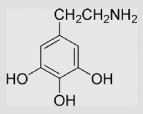

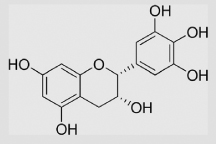

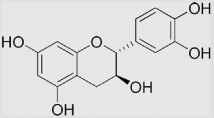

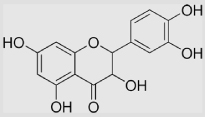

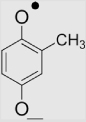

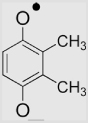

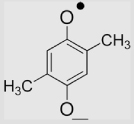

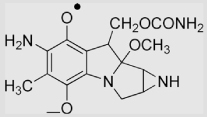

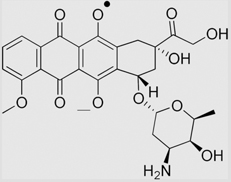

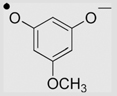

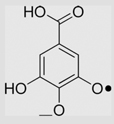

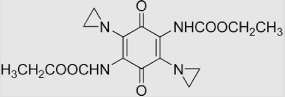

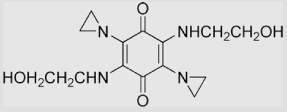

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of quinones.

The unique redox characteristics of the Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad allow it to serve as a one-electron as well as a two-electron acceptor/donor. An important chemical feature of quinones is the ability to undergo a reversible oxidation-reduction without a change in structure; i.e., the quinone/quinol ring remains intact thereby allowing redox cycling. In the context of the Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad, redox cycling would be enzymatic reduction of Q to SQ•− or H2Q and the subsequent oxidation to form superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. This futile cycle results in an apparent nonending shunting of electrons from cellular reducing equivalents to dioxygen, forming potentially damaging reactive oxygen species.

The goal of this paper is to provide information on the fundamental thermodynamics and kinetics of the reaction of semiquinone radical with dioxygen to form superoxide. We have collected in Table A1 the half-cell reduction potentials of many Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads. In Table A2 the second-order rate constants for the reaction of various semiquinones with dioxygen to form superoxide are tabulated. The thermodynamics of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads at near-neutral pH also provide insight into other reactions of the members of these triads, such as the Michael addition of nucleophiles, e.g., thiols. Insights into these chemistries are available when the relative electrophilicities of these species are taken into account; the pKas of hydroquinones serve as excellent reporters of the relative electrophilicities of members of these triads.

Half-cell reduction potentials, E°′, for Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads

Quinones are used as oxidizing agents in organic synthesis, e.g., 2, 3-dichloro-5, 6-dicyano -1, 4-benzoquinone [15], whereas hydroquinones are used as reducing agents, e.g., in photographic developers. However, the oxidizing and reducing abilities of these compounds vary greatly, depending on the nature of substituents on the ring, R2, R3, R5, and R6 of Fig. 1. Their relative oxidizing or reducing capacity can be assessed by half-cell reduction potentials.

The reduction of a quinone can occur in two sequential one-electron transfer reactions (Eqs. (1) and (2)) [16]. The complete reduction of a quinone to a hydroquinone requires two electrons and two protons (Eq. (3)) [17]. The intermediate semiquinone (SQ•−) is a relatively stable free radical, compared to highly reactive free radicals such as the hydroxyl radical; however, semiquinone radicals are relatively unstable species compared to quinones and hydroquinones. Semiquinones and hydroquinones readily undergo the reverse of Eqs. (1)–(3) in the presence of appropriate electron acceptors (oxidants, e.g., dioxygen).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The ease of reduction of a quinone or semiquinone is quantified by the half-cell reduction potential (E°′), when expressed in volts (V) or millivolts (mV) [18,19].1

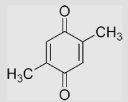

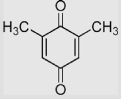

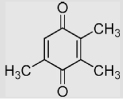

The more positive the reduction potential, the more easily the quinone or semiquinone is reduced. Conversely, the more negative this potential the more difficult it is to reduce the species. For example, 1,4-benzoquinone has a standard one-electron half-cell reduction potential of +99 mV to form benzosemiquinone; duroquinone (D-SQ•−), which has four methyl substituents on the quinone ring, has E°′ = −240 mV. Thus, 1,4-benzoquinone is much easier to reduce than duroquinone, i.e., it is a better oxidizing agent; however, durosemiquinone will be a stronger reducing agent than benzosemiquinone.

The chemistry of cells and tissues is clearly not occurring under standard conditions. Given the standard potential of the half-cell, the reduction potential for a redox couple at nonstandard concentrations (E) can be calculated using the Nernst equation (Eq. (4). Here, Qr is the reaction quotient for the half-reaction, simply the ratio of the [reduced species]/[oxidized species],

| (4) |

R is the gas constant in appropriate units, 8.314 J K−1 mol−1, T is the temperature in Kelvin, F is the Faraday constant 9.6485 × 104 C mol−1, and n is the number of electrons in the reduction reaction. If in the Nernst equation we use log10 rather than natural logarithm, then, at 25 °C (298.15 K), 2.3RT/nF = 59.1/n (mV); at 37 °C, 2.3RT/nF = 61.5/n (mV). Then, Eq. (4) will have the form:

| (5) |

With this form of the Nernst equation, real-world estimates are easily made from the quantitative information under standard conditions. Cells and tissues have a relatively reduced redox environment compared to that of the biosphere; these potentials have a limited range to be compatible with life [20,21].

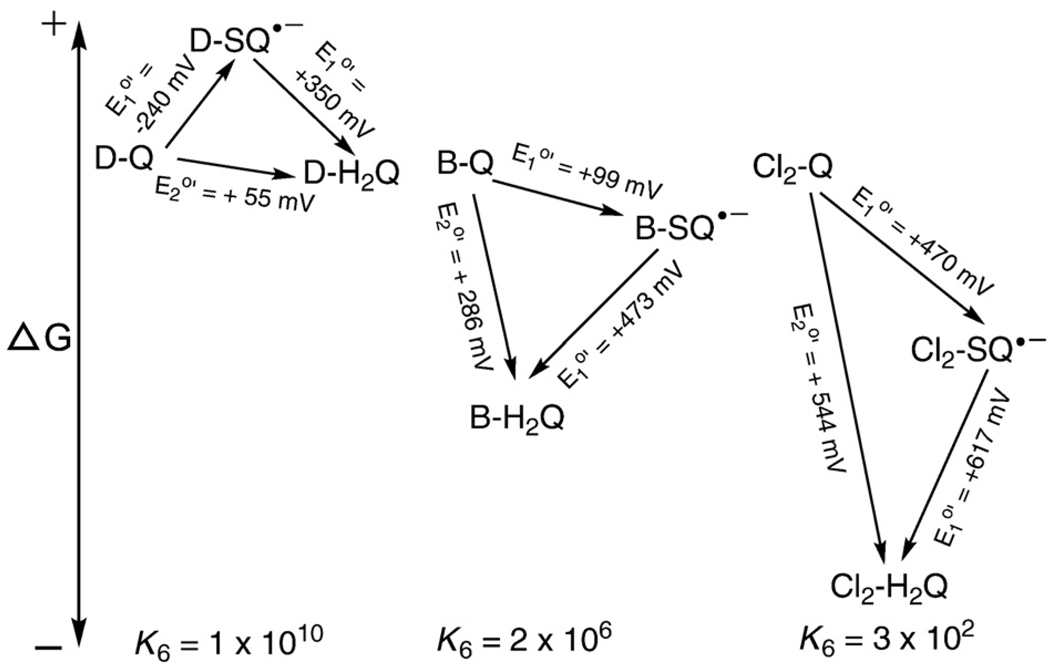

Quinones can undergo two sequential one-electron oxidations, Q/SQ•− and then SQ•−,2H+/H2Q.2 Each step will have a distinct reduction potential. For example, for the first electron for duroquinone, E°′(Q/SQ•−) = −240 mV, while for the second electron E°′(SQ•−,2H+/H2Q) = + 350 mV. These potentials indicate that the durosemiquinone is relatively3 reducing and at the same time it could also oxidize an appropriate electron donor by one electron to form H2Q.

Since SQ•− can be both oxidizing and reducing, it will readily disproportionate to its corresponding hydroquinone and quinone (Eq. (6) and Fig. 3). This reaction requires two protons:

| (6) |

Fig. 3.

The disproportionation (dismutation) reaction of semiquinone radicals is spontaneous and reversible at pH 7. Shown are the standard one-electron and two-electron reduction potentials for the duroquinone (D-Q), benzoquinone (B-Q), and 2,5-dichlorobenzoquinone (Cl2-Q) triads. Under standard conditions, i.e., ≈ 1.0 M concentration for each species, the dismutation reaction will be spontaneous because the overall change in the Gibbs free energy is favorable. A positive change in ΔE will yield a negative value for the change in the Gibbs free energy (ΔG=−nFΔE), indicating a spontaneous process. However, comproportionation of Q and H2Q to yield SQ•− is also possible when the value of the mass action expression for the system is not equal to the equilibrium constant. For Eq. (6), the complete mass action expression will be Qr=[Q][H2Q]/[SQ•−]2[H+]2. However, E°′ is the reduction potential at pH 7; thus, at this fixed pH, the mass action expression can be simplified to Qr=[Q][H2Q]/[SQ•−]2, because [H+] is constant. The equilibrium constants shown were determined with this form of Qr. The equilibrium constant for the disproportionation reaction (Eq. (6)) for a Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad can be determined using . At equilibrium ΔE = 0. If Qr<K, the reaction will proceed to the right until equilibrium is achieved; if Qr>K the reaction will proceed to the left; K is the equilibrium constant. (The quinones of each triad are shown with the same relative free energies. This was done only to conveniently show the relative changes in the free energy of each triad; it is not meant to imply they have the same Gibbs free energy.)

The rate for the forward reaction of Eq. (6) will slow as the pH is increased [22,23]. Thus, as the pH of a solution is raised semiquinone radical will become more persistent, allowing for a greater steady-state concentration and ease of detection, for example, by EPR spectroscopy (assuming no other chemistry is introduced) [24].

However, the reversible nature of these oxidations and reductions is shown by the comproportionation reaction of a quinone and hydroquinone yielding two SQ•−, reverse of Eq. (6). Because the reaction of Eq. (6) is reversible, the mixing of Q and H2Q will result in SQ•− being formed via comproportionation. Thus, when both Q and H2Q are present, there will always be some SQ•− in the system. How much will depend on the thermodynamics (equilibrium constant, K) for the reaction of Eq. (6), the pH, and the presence or absence of oxygen.

In Fig. 3 we present the thermodynamics of three different Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads graphically. Here we see that durosemiquinone is energetically “uphill” with respect to both D-Q and D-H2Q. Thus, the equilibrium constant for the reaction of Eq. (6) is large; i.e., the concentration of D-SQ•− will be very low at equilibrium. For both B-SQ•− and Cl2-SQ•− it is energetically “uphill” to the quinone; however, to get to the hydroquinone is energetically downhill. The overall energetics yields smaller equilibrium constants. With these smaller equilibrium constants for the dismutation reaction we would predict that semiquinone radicals would be present at relatively higher concentrations. They would appear as more persistent (and detectable) radicals when Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads are examined by EPR [25].

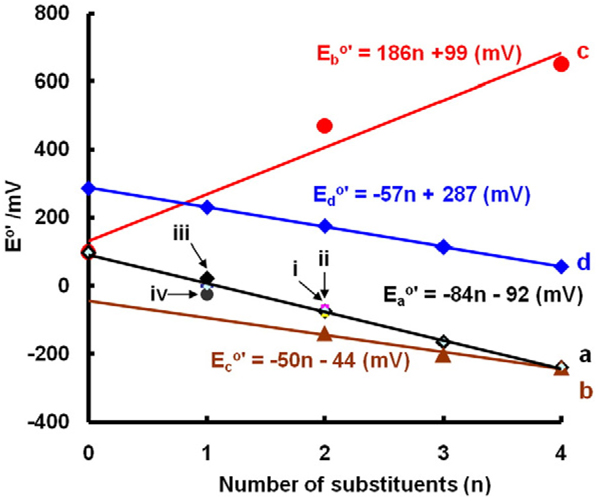

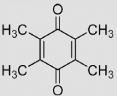

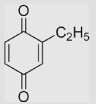

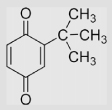

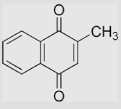

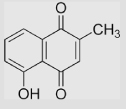

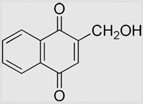

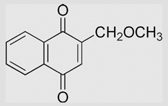

The substituents on a quinone ring can have a significant influence on the reduction potentials of the triad. For example, alkyl groups donate electrons into aromatic systems. As methyl groups are added to a benzoquinone ring, we would expect the resulting quinone to be less electrophilic; it should be “harder” to put an electron into Q to form SQ•−; we would expect the one-electron reduction potentials to become more negative with increasing numbers of alkyl substituents. Indeed, as one, two, three, and then four alkyl groups are added to the benzoquinone ring, we see a linear decrease in the one-electron reduction potential of Q (Fig. 4 line a). As might be expected, this pattern holds for 1,4-naphthoquinones as well (Fig. 4 line b).

Fig. 4.

Substituents influence E°′(Q/SQ•−) and E°′(Q, 2H+/H2Q) of quinones. (a) E°′(Q/SQ•−) vs number of alkyl groups on the benzoquinone ring: (i) all three isomers of dimethyl-benzoquinone are included (2,3-dimethyl, 2,5-dimethyl, and 2,6-dimethyl); they are similar so the points overlap on this plot; (ii) 2-methyl-5-iso-propyl-benzoquinone; again it is similar and overlap; (iii) ethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (iv) tert-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone. (b) E°′(Q/SQ•−) vs number of methyl groups on 1,4-naphthoquinone; here we treat the second ring as benzoquinone with two alkyl groups. (c) E°′(Q/SQ•−) vs number of chlorines on benzoquinone. (d) vs number of methyl groups on benzoquinone. Note these are two-electron half-cell reduction potentials.

If electron-withdrawing substituents (relatively electronegative, e.g., chlorine and bromine) are added to a benzoquinone ring, we would anticipate that the resulting quinone will be more electrophilic. Thus, it should be “easier” to put an electron into Q to form SQ•−. Indeed, the one-electron reduction potentials of chlorine-substituted quinones become more positive with increasing numbers of chlorines (E°′ = +99 mV for (benzoquinone), +470 mV for dichloroquinone, and +650 mV for tetrachloroquinone (Fig. 4 line c).

This principle also holds for two-electron reduction potentials of quinones. A plot of E°′(Q/H2Q) vs number of methyl substituents on benzoquinone demonstrates a linear decrease in the two-electron reduction potential (Fig. 4 line d). These trends allow estimates of E°′ for triads for which experimental data are not yet available. In addition, these potentials provide information for the understanding of the reactions of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads with nucleophiles and dioxygen.

Superoxide and superoxide dismutase

A potentially important reaction for semiquinones is their reaction with dioxygen to form superoxide (Eq. (7)). As indicated, this is an equilibrium reaction; the product quinone can be

| (7) |

reduced by superoxide; reverse Eq. (7). The equilibrium position of Eq. (7) is determined by E°′(Q/SQ•−) and . Using the potentials of the quinones listed in Table A1, the equilibrium constant (K) for the reaction of Eq. (7) can be determined. The reduction potential for the couple was initially determined to be −155 mV(1.0 M O2) [26,27]. However, a careful reexamination of this couple indicates that a better value is −180 mV[28,29]. Using and E°′(Q/SQ•−) = +99 mV for benzoquinone, in conjunction with Eq. (8), the equilibrium constant for reaction (7), where SQ•− is benzosemiquinone, is estimated as 2 × 10−5; for durosemiquinone the equilibrium constant at pH 7.0 is estimated to be 26.

| (8) |

If a quinone has E°′(Q/SQ•−) lower than the one-electron reduction potential of oxygen (<− 180 mV), e.g., mitomycin C, adriamycin, and menadione, the equilibrium position for the reaction of Eq. (7) will lie to the right, favoring formation of superoxide. For those quinones that have E°′(Q/SQ•−) greater than −180 mV, the equilibrium of Eq. (7) will lie to the left, and the generation of superoxide will not be thermodynamically favorable. However, it must be kept in mind that “not thermodynamically favorable” does not mean that superoxide will not be formed. Because K = kforward/kreverse, not thermodynamically favorable means that the reverse rate constant is greater than the forward rate constant. Thus, superoxide can be formed; however, the consequences of its formation in biological systems will be a function of the rate of formation of the semiquinone and the presence of reaction targets other than quinone.

One of these potential reaction targets is the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). SOD is an important antioxidant enzyme involved in removing superoxide and thereby protecting cells against oxidative damage; it reacts rapidly with superoxide radical (k = 2.4×109 M−1 s−1 [30]), facilitating its dismutation, thereby keeping a low steady-state level (Eq. (9)). In cells and tissues it will compete favorably with quinone for superoxide, thereby pulling reaction (7) to the right, even if reaction (7) is not “thermodynamically favorable” [24,31].

| (9) |

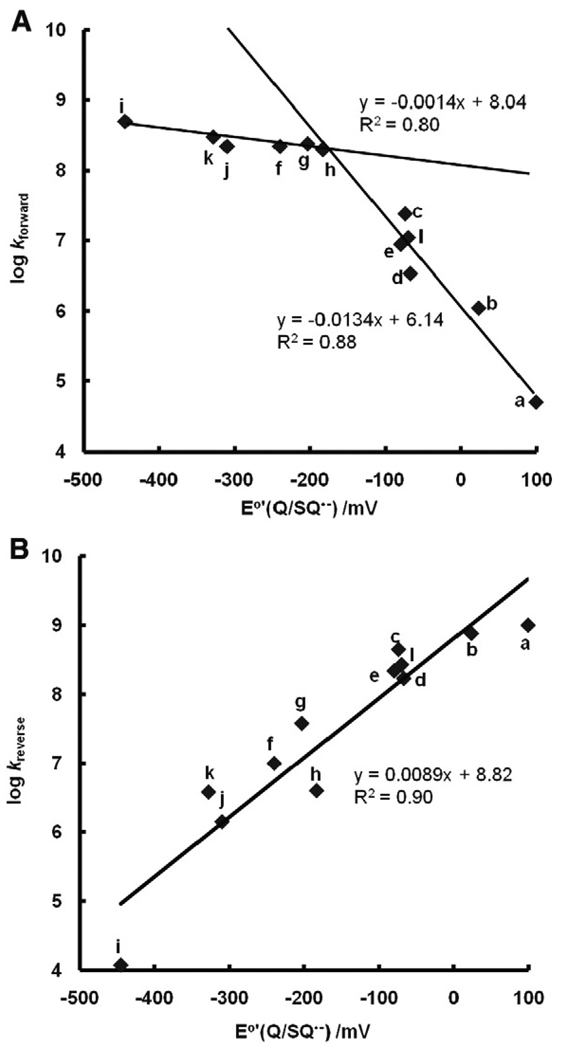

Because O2 has no charge, the Marcus theory of electron transfer predicts that the rate constants for the reaction of SQ•− with O2 (Eq. (7)) (Table A2) will be a function of the change in the Gibbs free energy for this reaction. A plot of log kforward vs E°′(Q/SQ•−) for a subset of the Q/SQ•− couples of Table A1 shows two distinct groups, each having an approximate linear relationship (within the noise of the available data) (Fig. 5A). Detailed analyses by Meisel [32] and Wardman [23] show a gentle parabolic shape, mostly in accord with the Marcus theory. In Fig. 5A the data fall into two categories: (i) for E°′<−150 mV the rate constants appear to be influenced by diffusion, i.e., k> 108 M−1 s−1; and (ii) when E°′>−150 mV the rate constants follow well the Marcus theory for electron transfer, here approximated by a linear relationship.

Fig. 5.

Second-order rate constants for formation of superoxide by SQ•− (Eq. (7)), as well as the reverse reactions, are a function of E°′. (A) For the forward reaction, the rate constants fall into two categories: (i) when E°′<−150 mV the rate constants appear to be influenced by the diffusion limit, i.e., > 108 M−1 s−1; and (ii) when E°′>−150 mV the rate constants appear to follow the Marcus theory for electron transfer, here approximated by a linear relationship. (B) For the reverse reaction of Eq. (7), the rate constants correlate well with the one-electron reduction potential of the quinones. The specific semiquinone radical for each point has as the parent quinone: a, 1,4-benzoquinone; b, methyl-1,4-benzoquinone; c, 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; d, 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; e, 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; f, duroquinone; g, 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone; h, 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone; i, anthraquinone (estimated here for B); j, Mitomycin (estimated here for B); k, Adriamycin (estimated here for B); l, AZQ: 2,5-diaziridinyl-3,6-bis(carbethoxyamino)-1,4-benzoquinone.

On fitting the data of these two groups to separate linear functions, we can estimate kforward of Eq. (7) for different SQ•− if we know E°′(Q/SQ•−). For example, for 2,5-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone E°′(Q/SQ•−) = +470 mV, log kforward is estimated as −0.15 or kforward = 10(−0.15) = 0.7; for 2,3,5,6-tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone, kforward = 10(−2.57) = 0.003. Thus, the rate constants for formation of superoxide by semiquinone radicals can vary over at least 11 orders of magnitude: for anthraquinone E°′(Q/SQ•−) = −445 mV, k = 5 × 108 M−1 s−1, while for tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone, E°′(Q/SQ•−) = +650 mV, k = 3× 10−3 M−1 s−1 (estimated).

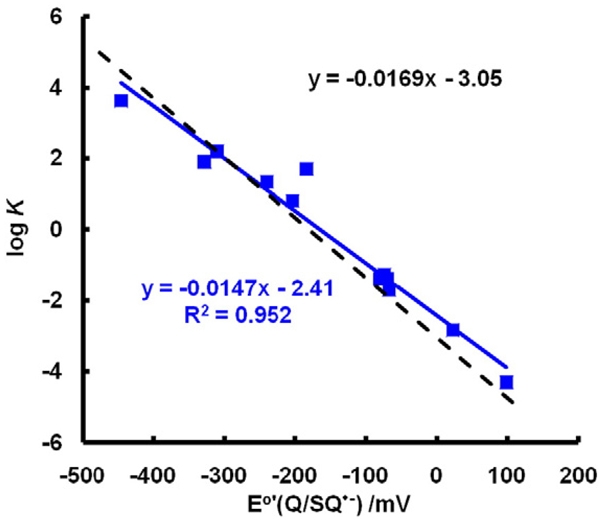

Making a similar plot for kreverse, i.e., log(kreverse) vs E°′(Q/SQ•−), we again see an approximate linear relationship (Fig. 5B). As might be expected, the larger the forward rate constant for Eq. (7), the smaller the rate constant for the reverse reaction. A plot of log(experimentally determined equilibrium constants) vs E°′(Q/SQ•−) yields a straight line as expected (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Experimental equilibrium constants match theoretical equilibrium constants closely. The dashed black line represents the theoretical values of K for Eq. (7) using the Nernst equation (Eq. (7)) with ; the slope of this line is 1/(59.1 mV) and the intercept is (−180 mV)/(59.1 mV). The variation in the experimental values represents the uncertainties of measurement. (Solid line, a fit of experimental data by linear regression.) However, if the very fast reactions of Eq. (7) are influenced by limitations from diffusion, then the largest forward rate constants are lower than theoretical rate constants, resulting in the corresponding Ks being underestimated. Likewise, when E°′(Q/SQ•−) is very positive, the experimental, very fast rate constants for the reverse reactions of Eq. (7) are lower than theoretical rate constants and, thus K would be overestimated. These two extremes may account for the shallower slope and the underestimation of the intercept for experimental values.

To understand how the presence of SOD will affect the reverse of Eq. (7), one needs to compare pseudo-first-order rate constants for the competing reactions of superoxide with SOD or quinone. Each reaction is second-order. The rate constant for the reaction of superoxide with SOD is 2 × 109 M−1 s−1 [33]. If we assume a typical concentration for CuZnSOD to be 20 µM in tissues [34,35], then the pseudo-first-order rate constant for the reaction of superoxide with SOD in cells is ≈ 4 × 104 s−1 . When the pseudo-first-order rate constant for the reaction of superoxide with is equal to 4× 104 s−1, then one-half of the superoxide will with react with SOD and one-half will react with Q, assuming no other significant “sinks” for superoxide. If , then the major fraction of superoxide will react with SOD; if this ratio is < 1, then the major fraction will react with quinone.

As an example, if for Eq. (7) kreverse = 106 M−1 s−1, then [Q] must be 40 mM just to compete on an equal basis with SOD; if kreverse = 109 M−1 s−1 then [Q] must be 40 µM to compete on an equal basis with SOD. A concentration of 40 mM Q inside a cell is quite unrealistic for most xenobiotics, even 40 µM seems challenging. Thus, we suggest that in nearly all circumstances, SOD will pull Eq. (7) to the right by competing against the reverse reaction [36–38]. SOD will lower the steady-state concentration of . However, if SQ•− is readily regenerated from Q and/or H2Q, then SOD will increase the flux of , which will then lead to an increased flux of H2O2 [38]. Thus, the rate of the forward reaction of Eq. (7) is a key factor in determining the flux of and H2O2 in cells and tissues.

pKa's

The pKa of a proton reflects the electron density on the atom with which it forms a hydrogen bond. In general the higher the electron density, the greater the negative charge, the higher the pKa, and vice versa. Because the core structure of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads is nearly the same, the pKa's of a hydroquinone will also reflect the relative electron density not only on the oxygens of the hydroquinone but also the relative electron density in the aromatic core of each member of a triad. Thus, the pKa's of hydroquinones will reflect the relative electron density in the aromatic core (electrophilicity) of a series of quinones and semiquinones, as well as the parent hydroquinone.

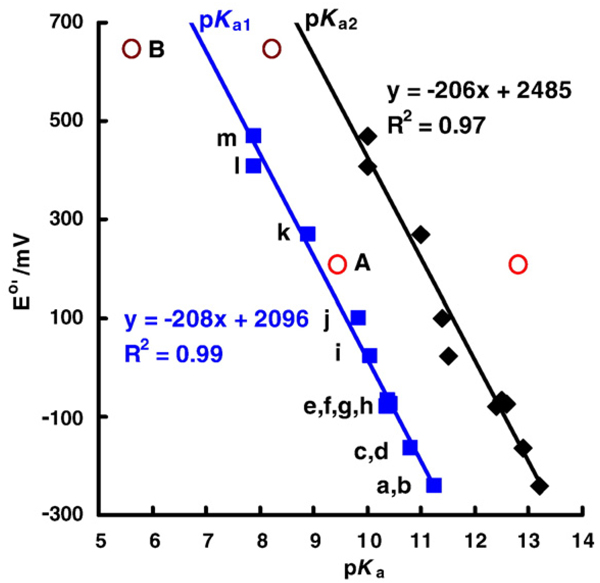

Hydroquinones are very weak diacids with first pKa's typically in the range of 9 – 11. The second pKa is uniformly 2.0 units higher (Fig. 7). From the trends seen in Figs. 4 and 7, we see, as expected, that electron-donating groups on the hydroquinone ring lead to higher pKa's, while electron-withdrawing groups lead to lower pKa's. Protonated semiquinones (SQH•) will also have an associated pKa; this pKa is typically in the range of 4 – 5 [13]. Thus, in near-neutral aqueous solution semiquinone radicals will exist primarily in their anionic, i.e., nonprotonated form (SQ•−), while hydroquinones will in general exist as H2Q with smaller amounts of HQ− (in general <1%); the concentration of Q2− will be about 1% of that of HQ−.

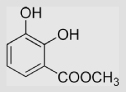

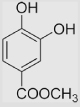

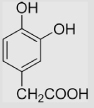

Fig. 7.

E°′(Q/SQ•−) correlates with the pKa's of the corresponding para-hydroquinones. The squares ( , blue) are the first pKa of a particular hydroquinone; the diamonds (◆, black) are the second pKa of the hydroquinone; pKa's are from [11,12,39]. The para-quinones/hydroquinones a–m show a linear relationship between the one-electron reduction potential of the quinone (E°′(Q/SQ•−)) and the first and second pKa's of the corresponding hydroquinone. The one-electron reduction potentials for quinones k and l have been estimated from Fig. 4; compounds A (catechol) and B (tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone) are not included in the linear regression of the two lines. We anticipate that ortho-hydroquinones would behave similarly to para-hydroquinones, but there would most likely be a systematic offset relative to the plots for para-hydroquinones. (A note on tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone: E°′(Q/SQ•−) for tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone (B) has been estimated from the correlation of the reduction potentials determined in methyl cyanide [40,78]; knowing that pKa1 for tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone is 5.6 [12] suggests that the one-electron reduction potential is actually about +800 mV in aqueous solution.) The compounds are: a. ubiquionol-1, coenzyme Q-1; b, tetramethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; c, 2,3,5-trimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; d, plastoquinol-1; e, 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; f, 2-methyl-5-isopropyl-1,4-hydroquinone; g, 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; h, 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; i, 2-methyl-1,4-hydroquinone; j, 1,4-hydroquinone; k, 2-chloro-1,4-hydroquinone; l, 2,6-dichloro-1,4-hydroquinone; m, 2,5-dichloro-1,4-hydroquinone; A, catechol; B, tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone.

, blue) are the first pKa of a particular hydroquinone; the diamonds (◆, black) are the second pKa of the hydroquinone; pKa's are from [11,12,39]. The para-quinones/hydroquinones a–m show a linear relationship between the one-electron reduction potential of the quinone (E°′(Q/SQ•−)) and the first and second pKa's of the corresponding hydroquinone. The one-electron reduction potentials for quinones k and l have been estimated from Fig. 4; compounds A (catechol) and B (tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone) are not included in the linear regression of the two lines. We anticipate that ortho-hydroquinones would behave similarly to para-hydroquinones, but there would most likely be a systematic offset relative to the plots for para-hydroquinones. (A note on tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone: E°′(Q/SQ•−) for tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone (B) has been estimated from the correlation of the reduction potentials determined in methyl cyanide [40,78]; knowing that pKa1 for tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone is 5.6 [12] suggests that the one-electron reduction potential is actually about +800 mV in aqueous solution.) The compounds are: a. ubiquionol-1, coenzyme Q-1; b, tetramethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; c, 2,3,5-trimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; d, plastoquinol-1; e, 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; f, 2-methyl-5-isopropyl-1,4-hydroquinone; g, 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; h, 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-hydroquinone; i, 2-methyl-1,4-hydroquinone; j, 1,4-hydroquinone; k, 2-chloro-1,4-hydroquinone; l, 2,6-dichloro-1,4-hydroquinone; m, 2,5-dichloro-1,4-hydroquinone; A, catechol; B, tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone.

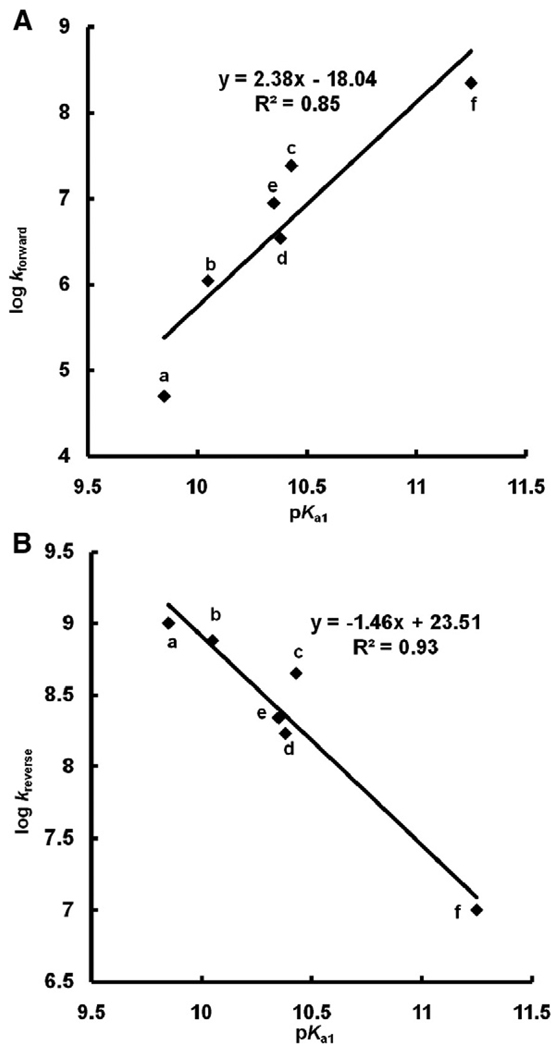

From Fig. 7 it is clear that the pKa's of a hydroquinone are outstanding indicators of the one-electron reduction potential of the corresponding quinone; E°′(Q/SQ•−) is determined by the nature of the “R groups” on the quinone/hydroquinone ring, which is reflected in the pKa's. In Fig. 5 we see that the rate constants for the reactions of Eq. (7) are a function of E°′(Q/SQ•−); thus, it would appear that the pKa's of H2Q are outstanding indicators of relative electron densities, providing a window to understanding the production of by SQ•− at near-neutral pH. In fact, a plot of the log(forward rate constant) or log(reverse rate constant) for Eq. (7) vs pKa1 of the corresponding hydroquinone shows a linear relationship (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Second-order rate constants for formation of superoxide by SQ•− (Eq. (7)) as well as the reverse reactions are a function of pKa1. pKa's are from Fig. 5. The para-hydroquinones a–f show a linear relationship between the rate constant of formation of semiquinone (Eq. (7)) as well as corresponding reverse Eq. (7) vs the first pKa's of the corresponding hydroquinone. The compounds are: a, 1,4-benzoquinone; b, methyl-1,4-benzoquinone; c, 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; d, 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; e, 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; f, duroquinone.

Essentially we see that electron-withdrawing groups on the semiquinone ring will lead to a less reactive (less reducing), more persistent free radical that reacts relatively slowly with dioxygen to produce superoxide. Conversely, electron-donating groups result in a more reducing semiquinone radical that is less persistent and will readily react with dioxygen to produce superoxide. These properties at near-neutral pH are related to the electron densities in the aromatic moiety of the semiquinone and are reflected in the pKa's of the hydroquinone (Figs. 5 and 7. There must be a near linear offset in the overall electron density in the aromatic moiety of a triad as we go from Q to SQ•− to QH2, so it all works.

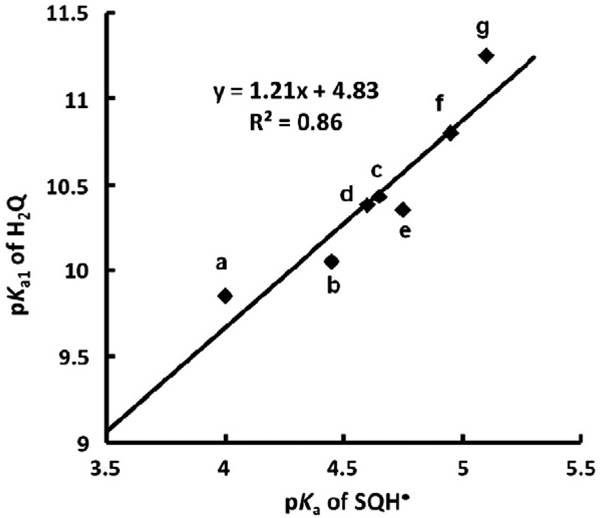

That there is indeed a linear offset in the electron density, i.e., relative electrophilicity, in the members of a Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad is seen when the first pKa's of hydroquinones are compared to the pKa's of corresponding protonated semiquinones (Fig. 9). This linear relationship supports the use of pKa's to understand the chemistry of these triads.

Fig. 9.

There is a linear relationship of pKa1 of H2Q with pKa of the corresponding SQH•. (a) 1,4-Benzoquinone; (b) methyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (c) 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (d) 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (e) 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (f) 2,3,5-trimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (g) duroquinone.

There are now many computational tools to estimate the pKa's of a broad range of organic compounds, including hydroquinones. With these pKa's it would be possible to estimate E°′ (Q/SQ•−) and the other reduction potentials of a triad and even rate constants for Eq. (7) based on the data from a series of triads that have similar structures and properties.

A broader approach to understanding the reactivity and mechanisms of toxicity of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads would be to use the electrophilicity index or similar approaches [41–43]. However, this is beyond the scope of this paper.

Hydroquinone autoxidation

The autoxidation of hydroquinones has been studied for over a century [44,45] (autoxidation is oxidation in the absence of metal catalysts [46].) In general, autoxidation of hydroquinones to corresponding quinones results in the stoichiometic production of H2O2. The oxidation is pH dependent; the rate increases as the pH increases [47]. In homogeneous aqueous solution, the rate law for the autoxidation of a family of 1,4-hydroquinones has been observed to be first-order with respect to [H2Q] and [O2]; however, it is second order in [OH−] [48–50]. This oxidation can be inhibited by reducing agents [51–53]; the rate law can change in the presence of catalysts [16,54].

Because kinetic studies at near-neutral pH have found that the initial rate of oxidation of 1,4-hydroquiones is second order in [OH−], the key species in the autoxidation of hydroquinones is Q2−; i.e., Q2− is the species that actually undergoes autoxidation, Eqs. (10)–(13).

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

The reaction of Eq. (12) is spin-restricted and thus expected to be quite slow [46]. Here we indicate H2O2 as the product of Eq. (12) and of the overall reaction Eq. (13), as observed by researchers over the decades. However, the reaction of Eq. (12) will most likely occur as two sequential steps with superoxide and semiquinone as intermediates. The actual mechanism can be quite complex and Eqs. (10)–(13) as written are not intended to convey the detailed mechanism of every oxidation. The mechanism will change if metals are present or if superoxide is a chain-carrying radical in the oxidation process; see below (Catalysts for oxidation of H2Q). As an example of Eqs. (10)–(13), the ascorbate dianion undergoes true autoxidation, a reaction parallel to Eq. (12), with a rate constant of about 200 M−1 s−1 [55]. Thus, the initial rate of autoxidation of a hydroquinone at near-neutral pH will actually be a function of [Q2−]. The lower the pKa's of a hydroquinone, the greater the concentration of Q2− at near-neutral pH. Thus, electron density in the aromatic moiety of hydroquinones, as reflected in its pKa's, is central to its rate of autoxidation.

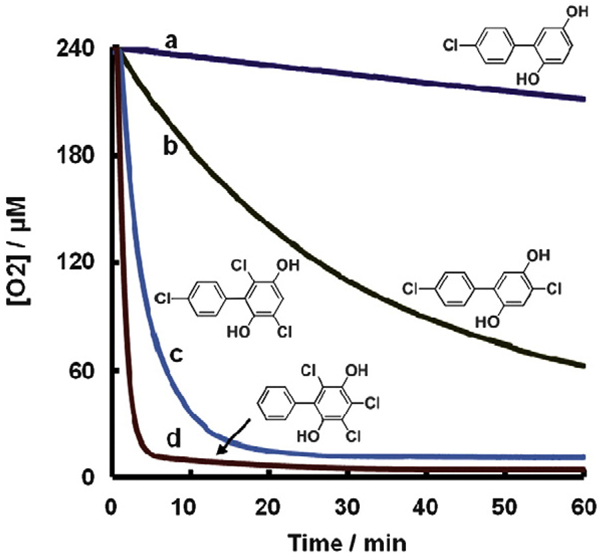

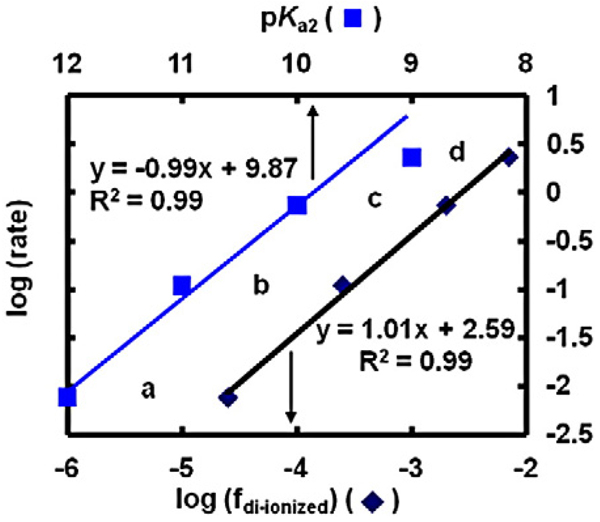

A clear example of this is seen in the autoxidation of a series of chlorinated 1,4-hydroquinones (Fig. 10). The rate of autoxidation of this family of hydroquinones, as measured by the rate of oxygen consumption, increases with increased chlorination of the hydroquinone ring. The initial rates for the autoxidation of this set of chlorinated hydroquinones at pH 7.4 increases by a factor of 10 as the number of chlorines on the oxygenated ring increases from 0 to 3 (Fig. 11) [56]. The factor of 10 increase in the rate of autoxidation follows closely the lowering of the pKa's of the hydroquinone by one pKa unit on the addition of each chlorine to the hydroquinone ring, except for the trichlorinated hydroquinone (Fig. 11). If the rate constants for the reaction of Eq. (12) are similar for each Q2−, then the rate of autoxidation will be proportional to the concentration of Q2−. Indeed, when log(rate) is plotted against the fraction of hydroquinone present in the di-ionized form (Q2−), we see a slope of exactly 1.0, consistent with the reaction of Eq. (12) being central in the autoxidation hydroquinones in near-neutral solution. This is seen in the slope of the lines being exactly 1.0. These data suggest that for the rate law −d[O2]/dt = −k[Q2−][O2], k = 2 × 102 M−1 s−1. This rate constant appears to hold across all Q2− in this series; interestingly this is also consistent with that observed for the ascorbate dianion [55].

Fig. 10.

Time course of oxygen consumption during the autoxidation of PCB hydroquinones with different degrees of chlorination on the oxygenated phenyl ring. (a) 4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; (b) 4,4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; (c) 3,6,4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; and (d) 3,4,6-Cl-2,5-H2Q. Solutions contained [H2Q] = 2.0 mM in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer at 25 °C. Adapted from [56].

Fig. 11.

The rate of O2 consumption (µM s−1) increases with the fraction of the di-ionized hydroquinone, which is determined by the number of chlorines on the ring. Rates were determined from the initial slopes for the uptake of oxygen in Fig. 10. (a) 4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; (b) 4,4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; (c) 3,6,4′-Cl-2,5-H2Q; and (d) 3,4,6-Cl-2,5-H2Q. A plot of log(rate) vs pKa2 of the hydroquinone works well except for (d). However, pKa1 for (d) is 7; thus there is not an approximate factor of 10 increase in the concentration of Q2−, compared to (c), because the solution pH is 7.4. However, when the log of fraction di-ionized (fdi-ionized) is plotted against log(rate), all points fit. The fraction of di-ionized (fdi-ionized) H2Q was determined in pH 7.4 buffer, by using pKa2 of the H2Q's as 12, 11, 10, and 9 for H2Q with 0, 1, 2, and 3 chlorines on the oxygenated ring, respectively [56]. The values are pKa1 + 2, as indicated by Fig. 7. A slope of 1.0 indicates the reaction is first-order in [di-ionized hydroquinone].

The experimental observation that electron-withdrawing groups on a semiquinone ring result in semiquinones that are more persistent compared to when there are electron-donating groups on the ring appears [25] to be at odds with the observation that electron-withdrawing groups make the hydroquinone more susceptible to autoxidation. As discussed above, both observations can be related to the pKa's of the parent hydroquinone. Thus, you cannot win—a Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad that readily produces superoxide via SQ•− will have a relatively stable hydroquinone, with respect to autoxidation; however, a Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad that has a semiquinone that reacts very slowly with dioxygen to produce superoxide will have a hydroquinone that readily undergoes autoxidation to produce hydrogen peroxide.

Catalysts for oxidation of H2Q

The above discussion focuses on the autoxidation of hydroquinones. However, catalysts can accelerate the oxidation of hydroquinones. For example, redox-active transition metals, e.g., manganese, iron, and copper, will serve as catalysts for the oxidation of hydroquinones [16,54,57–60]. These metals assist in overcoming the spin restriction by forming complexes with the monoanion (HQ−) as they facilitate the electron transfer to dioxygen. In autoxidation, the kinetic rate law is second-order in [OH−]. However, in metal-catalyzed oxidations, the rate law is often first-order in [OH−], consistent with the monoanion being the important species in this route of oxidation. Redox-active metals are ubiquitous; adventitious metals are present on glassware and in all buffer solutions unless measures are taken to remove them [61]. Redox-active metals with appropriate coordination environments accelerate the oxidation of hydroquinones compared to autoxidation, principally by changing the mechanism.

Another, often overlooked, catalyst for the oxidation of H2Q is the quinone formed as a product. This has been demonstrated by the observation of an apparent “self-acceleration” during the autoxidation of many hydroquinones. The reaction kinetics show a significant induction (lag) period that can be eliminated by addition of very small amounts of Q [24,62]. When Q is present, the reverse of Eq. (6) will occur, i.e., H2Q and Q will comproportionate to form 2SQ•−; SQ•− will then react with dioxygen to produce , Eq. (7); will dismute, either spontaneously or as catalyzed by SOD to form H2O2 in biological systems. Thus H2Q is oxidized, Eq. (13), albeit by a different mechanism than autoxidation.

Quinone will only be an efficient catalyst if the corresponding semiquinone radical reacts readily with dioxygen to form superoxide. When a semiquinone has electron-withdrawing groups on the ring, the rate constant for the reaction of SQ•− with dioxygen to form (Eq. (7)) will be small; electron-donating groups result in higher values for the rate constant for superoxide production. Thus, the efficiency of Q/SQ•− in the catalysis of the oxidation of H2Q is really a function of how efficiently SQ•− forms superoxide.

SOD can accelerate the rate of oxidation of some hydroquinones [24,62]. SOD removes superoxide, Eq. (9), forming H2O2. By removing , SOD increases the rate of formation of both H2O2 and of quinone, the two end products of oxidation of H2Q. Thus, SOD accelerates the overall rate of oxidation of certain hydroquinones by minimizing the reverse of Eq. (7) as well as providing Q, which can serve as an apparent catalyst. SOD will have the greatest effect on the rate of oxidation of hydroquinones that have electron-donating substituents on the ring because it will increase the rate of formation of Q, a catalyst.

SOD can also slow the rate of autoxidation of some substances, e.g., when the superoxide produced is also a chain-propagating species. For example, the oxidation of epinephrine (adrenaline), a catechol, has been the subject of many studies [63]. It readily autoxidizes at higher pH and trace catalytic metals can accelerate its air oxidation. On the discovery of SOD, it was then found that autoxidation of epinephrine produces superoxide and this superoxide can serve as a chain-carrying radical [64]. Removing this chain-carrying radical by SOD will slow its oxidation. These reactions form the basis of an activity assay for SOD [64].

The oxidation of hydroxylated aromatics can be quite complex [65]. For example, the air oxidation of dialuric acid (2,4,5,6-tetrahydroxypyrimidine) can be accelerated by catalytic metals [66], as well as the presence of its two-electron oxidation product, alloxan. Dialuric acid and alloxan will undergo a comproportionation reaction, parallel to the reverse of Eq. (6), forming a reducing radical parallel to SQ•−, which will in turn react with dioxygen to form superoxide [65]. Superoxide is a chain-carrying radical in this system; thus, the presence of SOD will change the rate as well as the form of the kinetic rate law of this oxidation. The kinetic rate law that describes the oxidation can change considerably, depending on the environment and the mechanism that dominates the oxidation [65].

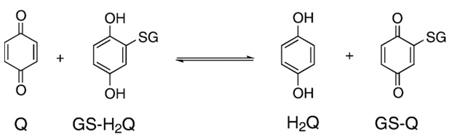

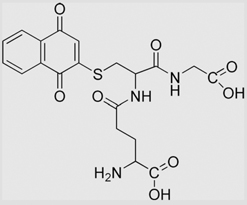

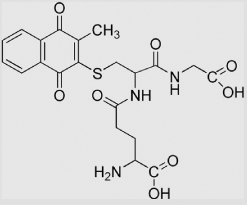

Thiols/GSH, addition of nucleophiles to quinone compounds

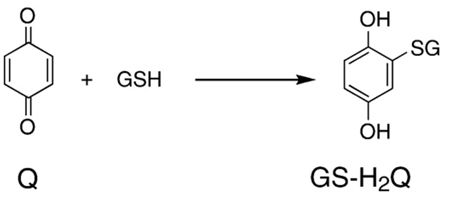

Above we have focussed on the oxidation reactions of the Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad and the associated production of and H2O2. However, because quinones are electrophilic, they have another chemistry that can be the principal mechanism for their toxicity, i.e., the reductive addition (Michael reaction) of nucleophiles such as amines and thiols [67–69]. Eq. (14) is representative of this type of reaction with quinones; showing the reductive addition of glutathione to B-Q to form a monothiol ether of benzohydroquinone, GS-H2Q. On oxidation of GS-H2Q to GS-Q, another reductive addition can occur to yield (GS)2-H2Q; this cycle of oxidation and reductive addition can occur until all four “open” sites on benzoquinone are glutathionylated [56,68]. The rate constant for the addition reaction of the first thiol to benzoquinone is on the order of 105 M−1 s−1 in pH 6.0 buffer [70]. Because the kinetics of nucleophilic addition of a thiol to a quinone ring is controlled by the concentration of the ionized form of the thiol, the rate constant for thiol addition to benzoquinone at pH 7 will be about 10 times faster, i.e., k is on the order of 106 M−1 s−1 [23,71,72].

|

(14) |

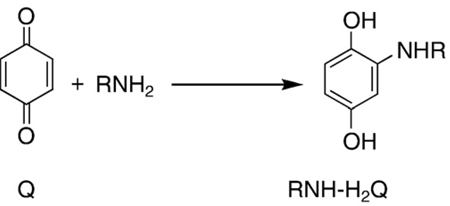

In addition to thiols, amine compounds can also serve as nucleophiles, undergoing reductive addition to Q, Eq. (15). Naturally, all free amino acids contain an RNH2 moiety, but in proteins the amine groups, such as on lysine and arginine, or the amine groups of DNA bases can also serve as appropriate nucleophiles for Eq. (15). Parallel with thiols, it is the unprotonated amine (R-NH2) rather than the protonated form that is the effective nucleophile. As amines are much weaker nucleophiles than thiolates (RS−), they react with benzoquinones much more slowly; rate constants for reductive addition of amino acids to Q are on the order of 10−2 M−1 s−1 in pH 7.4 buffer [73]. This difference of 108 in rate constants and the fact that the concentration of reactive thiols in cells and tissues is high indicate that the dominant reaction of quinones will be with thiolates rather than amines.

|

(15) |

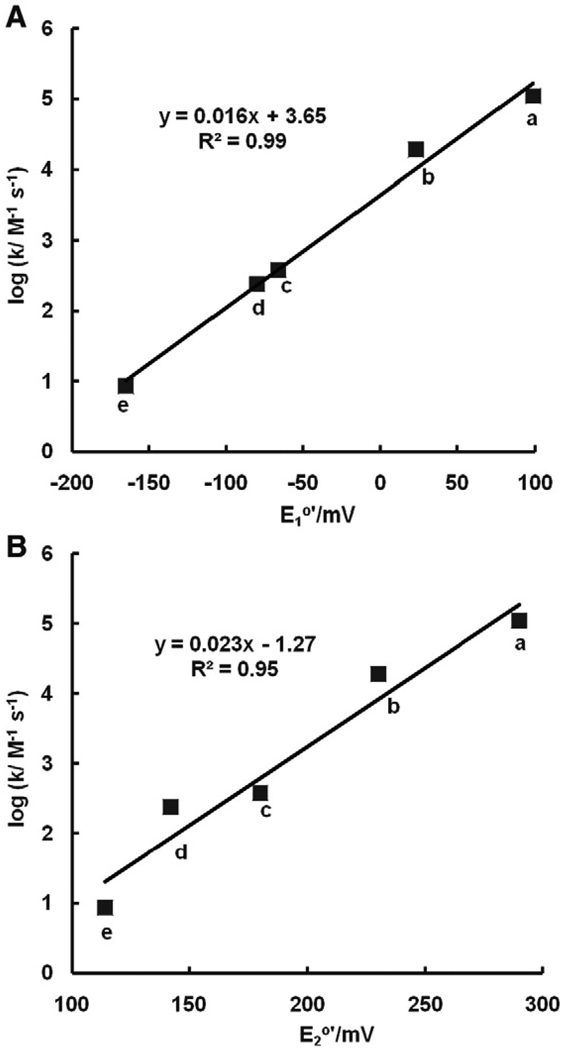

The actual rate constants for the reductive addition of nucleophiles to quinone rings will not only be a function of the nucleophilicity of the nucleophile, but also the electrophilicity of the quinone ring. As manifest in their wide range of half-cell reduction potentials, quinones have a wide range of electrophilicity. We would expect that quinones with very positive half-cell reduction potentials will react rapidly with nucleophiles, while quinones with lower reduction potentials will react more slowly [74]. Indeed, when log(rate constant) values for the reaction of glutathione with a series of benzoquinones are plotted against either the one-electron or two-electron reduction potential of the quinones, we see remarkable linear relationships (Fig. 12). Thus, the half-cell reduction potentials of quinones can be used to estimate rate constants for the reductive addition of nucleophiles (Eqs. (14) and (15)).

Fig. 12.

The rate constants for the Michael reaction of glutathione with various quinones are a function of E°′. The rate constants for reductive addition of GSH to benzoquinone and methylated benzoquinones decrease linearly with increasing degrees of methylation; methyl groups donate electrons into the quinone ring. (A) One-electron reduction potential for Q/SQ•−; and (B) two-electron reduction potential of the quinones, Q,2H+/H2Q. (a) 1,4-Benzoquinone; (b) methyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (c) 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (d) 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (e) 2,3,5-trimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone. Data from [70]. The kinetic data are at pH 6.0. Because it is actually the ionized thiol, here GS−, that dominates the reaction of Eq. (14), rate constants at pH 7 will be about 10 times larger.

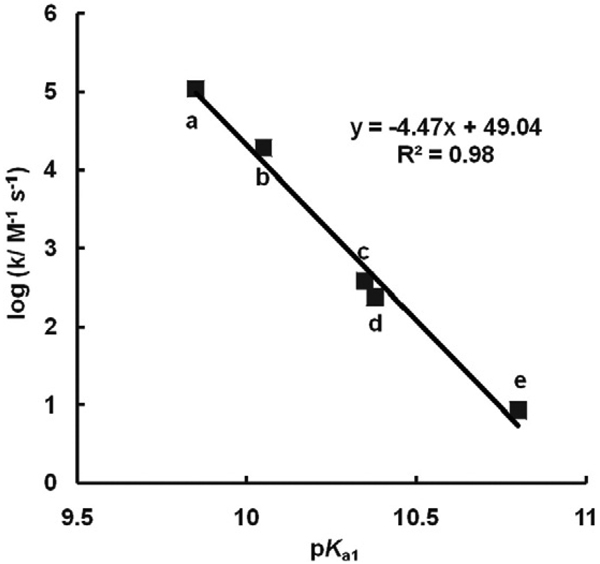

Because pKa is a measure of electrophilicity for members of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads, we would anticipate that rate constants for the reductive addition of nucleophiles, such as GSH, might also correlate well with rate constants for the addition reaction (Fig. 13). Thus, pKa's in combination with other information can be used to predict this aspect of the chemistry and even aspects of potential mechanisms of the toxicology of these types of compounds.

Fig. 13.

The rate constants for the Michael reaction of glutathione with various quinones are a function of pKa1 of the corresponding hydroquinone. The rate constants for reductive addition of GSH to benzoquinone and methylated benzoquinones decrease linearly with increase of pKa1. (a) 1,4-Benzoquinone; (b) methyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (c) 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (d) 2,5-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone; (e) 2,3,5-trimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone.

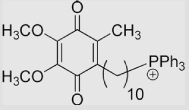

Coenzyme Q10 is an important redox species in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. The location of CoQ10 in membranes in not understood, but with a very large octanol/water partition coefficient (log(P) ≈ 20 [75]) it is clearly very lipophilic, residing in the lipid bilayer [3,76,77]. When in a lipid phase, the thermodynamics will be somewhat different, similar to the thermodynamics in an organic solvent. In general Eos of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads in organic solvents have similar relative values to the corresponding Eos in aqueous solution, but with an offset [23,78]. It is interesting to note that coenzyme Q has all four positions on the quinone ring occupied by alkyl and alkoxyl groups. Thus, Michael addition to the quinone ring is blocked, protecting CoQ from this type of chemistry.

Plastoquinone has a role in the electron transport chain of photosynthesis. It has one open site that could participate in a Michael addition reaction by appropriate nucleophiles (Fig. 2). However, the substituents on the plastoquinone ring have a net electron-donating effect, (estimated from Fig. 4 and Ref. [79]). Thus, a reductive addition reaction will be relatively slow, approximately ≈ 101 M−1 s−1 for a thiol (Fig. 12).

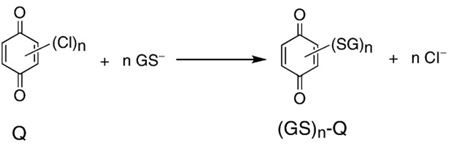

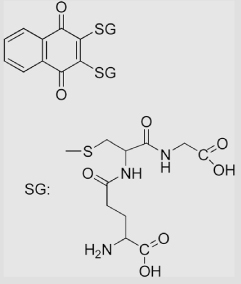

In addition to reductive addition (Michael reaction) strong nucleophiles can also displace weaker nucleophiles on a quinone ring. For example, thiolates, e.g., ionized glutathione (GS−), are strong nucleophiles that can displace chlorine on a quinone ring, Eq. (16). This

|

(16) |

type of reaction is typically facilitated by glutathione transferases [80,81]. However, it can also occur in the absence of enzymes, such as with halogen-substituted diaziridinylbenzoquinones [82], dioxygenated PCBs with chlorine on the quinone ring [56], as well as chlorinated naphthoquinones [83]. Because the product after the nucleophilic substitution reaction is still a quinone, more than one chlorine on a quinone ring can be displaced. In fact all four chlorines of tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone can be displaced by glutathione yielding tetra-glutathiyl-1,4-benzoquinone [56]. These substitution reactions are rapid and will be of significance in a biological milieu.

The autoxidation of hydroquinone generates hydrogen peroxide and quinone. Hydrogen peroxide is a nucleophile and has been shown to react with benzoquinone [24,49,84,85] as well as chlorinated benzoquinone [86]. Reductive addition can occur at higher pH environments because peroxide anion (HOO−) is a powerful nucleophile, much more reactive than hydroxide anion (pKa1 for H2O2 is 11.7 [87]). However, this reaction is most likely insignificant in vivo, as the amount of HOO− present will be infinitesimally small due to the neutral environment.

Cross-oxidation

The dismutation reaction of Eq. (6) is indeed an equilibrium reaction. If a quinone and hydroquinone are introduced into a solution, they will comproportionate to form two semiquinone radicals. The quinone and hydroquinone can be “different” resulting in two different semiquinone radicals; Eq. (17) is an example. The behavior of each of these radicals

|

(17) |

will be governed by their individual thermodynamics. The system will come to equilibrium with a ratio of two different quinones, two different hydroquinones (Eq. (18)), and smaller amounts of two different semiquinones [24];

|

(18) |

the ratio will all depend on the thermodynamics of each Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad. This is often referred to as a cross-oxidation; the rate can be relatively fast [71]. Naturally, if oxygen is present, then oxidation of the hydroquinones and semiquinones can occur, Eqs. (7) and (13).

Quinones are oxidants; thus, as noted above, they can oxidize species other than hydroquinones. For example, the more oxidizing quinones are capable of oxidizing NADPH [88]. For example, benzoquinone will oxidize NADPH with a rate constant on the order of 1 M−1 s−1 [88]. The rate constant will be smaller for quinones with more negative potentials, and conversely, larger with more positive potentials. Thus, half-cell reduction potentials can give insight into the wide range of reactions of members of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads.

Summary

In this treatise we provide a comprehensive overview of how the fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic properties of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads are intertwined. At near-neutral pH, the pKa's of the hydroquinone are outstanding indicators of these properties; i.e., they can be used to understand E°′ as well as the reaction kinetics for a range of reactions, including reactions with dioxygen to make and H2O2. However, E°′ can also guide our understanding of nucleophilic addition reactions to quinone rings.

Here we have presented and discussed details of:

Molecules containing a quinone/semiquinone/hydroquinone moiety can serve as either one- or two-electron acceptors/donors. The reduction of a quinone typically occurs in two sequential one-electron transfer reactions to generate hydroquinone via semiquinone.

The ability of the Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad to facilitate electron-transfer is dependent on the reduction potentials of the members of the triad. The more positive the reduction potential, the more easily the quinone or semiquinone is reduced. Conversely, the more negative this potential the more difficult it is to reduce the species.

The substituents on a quinone ring greatly influence the reduction potentials of the triad at neutral pH. Electron-withdrawing groups lead to higher reduction potentials (more positive); electron-donating substituents lead to lower reduction potentials (more negative).

Semiquinones can react with dioxygen to form superoxide. The more negative the reduction potential of a Q/ SQ•− redox couple, the greater the rate constant for production of superoxide by SQ•−; at the same time, the rate constant for the back reaction will be smaller, Eq. (7). These rate constants can vary over at least 11 orders of magnitude.

SOD can remove superoxide produced by SQ•−, thereby pulling the reaction of Eq. (7) to the right. This will result in an increase in the rate of formation of quinone, which can serve as a catalyst to increase the rate of autoxidation of hydroquinones. SOD can also increase the rate of hydrogen peroxide production from Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads in some settings [38]. If superoxide is a chain-carrying radical in an oxidation process, then SOD will slow the rate of oxidation of a hydroquinone.

The pKa's of a hydroquinone can serve as a barometer for the relative electron density in the aromatic moieties of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads (electrophilicity). Electron-donating groups on the hydroquinone ring lead to higher pKa's (lower electrophilicity), while electron-withdrawing groups lead to lower pKa's (higher electrophilicity).

The pKa's of a hydroquinone can be used to estimate the reduction potential of the members of a Q/SQ•−/H2Q triad as well as the kinetic rate constants for their reactions.

In general, autoxidation of hydroquinones to corresponding quinones results in the stoichiometic production of H2O2. The rate of oxidation is pH dependent; the rate increases as the pH increases. By changing the mechanism, catalysts, such as quinone and redox-active metals, can accelerate the oxidation of hydroquinones.

The reactions of hydroquinones are the result of formation of ionic species, QH− and Q2−.

Nucleophiles, e.g., amines and thiols, can react with quinones via the Michael reaction (reductive addition) yielding corresponding hydroquinone conjugates.

Thiolates, e.g., GS−, can displace chlorine on quinone rings via nucleophilic substitution.

The biochemistry and toxicology of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads are modulated by the presence of substituents on the aromatic ring that effectively determine their electrophilic properties. These properties dictate their reactions with both electrophiles and nucleophiles; they govern the kinetics of Eq. (7), both the forward and the reverse reactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants R01GM073929 from the NIGMS and P42ES013661 from the NIEHS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent views of the NIGMS, NIEHS, or the NIH. The University of Iowa ESR Facility provided invaluable support.

Abbreviations

- AZQ

2,5-diaziridinyl-3,6-bis(carbethoxyamino)-1,4-benzoquinone

- B-H2Q

benzohydroquinone

- B-Q

benzoquinone

- B-SQ•−

benzosemiquinone

- BZQ

5-diaziridinyl-3,6-bis(2-hydroxyethylamino)-1,4-benzoquinone

- Cl2-H2Q

2,5-dichlorobenzohydroquinone

- Cl2-Q

2,5-dichlorobenzoquinone

- Cl2-SQ•−

2,5-dichlorobenzosemiquinone

- D-H2Q

durohydroquinone

- D-Q

duroquinone

- D-SQ•−

durosemiquinone

- DETAPAC

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- E

nonstandard concentrations half-cell reduction potential

- E°

standard half-cell reduction potential

- E°′

standard half-cell reduction potential at pH 7.0

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- F

Faraday constant

- G

Gibbs free energy

- GSH

glutathione

- GS-H2Q

glutathionylated hydroquinone

- (GS)2-H2Q

diglutathionylated hydroquinone

- GS-SQ•−

glutathionylated semiquinone

- GS-Q

glutathionylated quinone

- RNH-H2Q

amino hydroquinone

- H2Q

a generic hydroquinone

- HO•

hydroxyl radical

- HQ−

a generic monoanionic hydroquinone

superoxide

- PCB

polychlorinated biphenyl

- Q

a generic quinone

- Qr

reaction quotient or mass action expression

- Q2−

a generic dianionic hydroquinone

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SHE

standard hydrogen electrode

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SQ•−

a generic semiquinone

- SQH•

a generic protonated semiquinone radical.

Appendix

Table A1 has collected information on the reduction potentials for members of Q/SQ•−/H2Q triads at pH 7. Table A2 presents kinetic information on Eq. (7), the formation of superoxide by various semiquinones. We have worked to minimize errors; we hope none remain

Table A1.

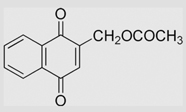

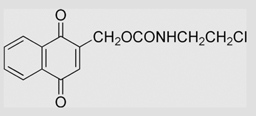

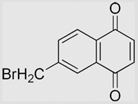

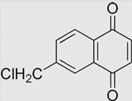

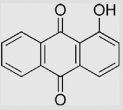

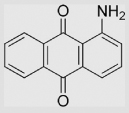

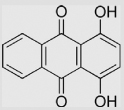

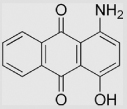

| No. | Compounds | Structure | E°′ (Q/SQ•−) /mV | E°′ (SQ•−/H2Q) /mV | E°′ (Q/H2Q) /mV | Ref | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

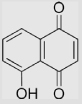

| 1 | Benzoquinone | ||||||

| 1.1 | 1,4-Benzoquinone | 78 99 |

448 459 473 23 57 1041 |

286 |

[78] [19,79] [89] [39] [39] [89] |

Calcn pH 13.5 pH ≈ 11 pH 0 (pKa of SQH• = 4.0) [13] |

|

| 1.2 | Methyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

23 23 |

460 437 414 |

230 | [89] [79] [78] |

Calcn |

| 1.3 | 2,3-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

−74 | 430 424 |

175 | [89] [79] |

Calcn |

| 1.4 | 2,5-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

−66 |

420 426 |

176 180 |

[89] [13] [79] |

Calcn (pKa of SQH• = 4.6) [13] |

| 1.5 | 2,6-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

−80 −80 |

363 | 142 | [78] [79,90] |

|

| 1.6 | 2,3,5-Trimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

−165 | 385 393 |

114 | [89] [79] |

Calcn |

| 1.7 | 2,3,5,6-Tetramethyl-1, 4-benzoquinone (Duroquinone) |

|

−264 −240 |

350 354 −54±5 |

68 |

[28] [79,89] [39] |

Calcn pH 13.5 (pKa of SQH• = 5.1 [13]) |

| 1.8 | Ethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

0 | 395 | −395 | [40,78] | Midpoint potentials: estimated based on the correlation of E(Q/SQ•−) with the structures of alkyl-substituted 1, 4-benzoquinone |

| 1.9 | t-Butyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

219±14 −25±6 −23±6 −32 |

1061±14 489±6 −75±15 453 |

[91] [91] [91] [78] |

pH 0 pH 7 pH 14 |

|

| 1.10 | 2-Methyl-5-iso-propyl-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

−70 | 358 | −428 | [40,78] | Estimated based on the correlation of E(Q/SQ•−) with the structures of alkyl-substituted 1, 4-benzoquinones |

| 1.11 | 2,6-Methoxyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

−150 | 187 | −337 | [78] | Midpoint potentials |

| 1.12 | 2,6-Methoxyl-3-methyl-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

−110 | ~290 | ~399 | [78] | Estimated from the correlation of E(Q/SQ•−) in aqueous buffer and that in MeCN |

| 1.13 | 2,3-Methoxyl-5-methyl-1, 4-benzoquinone (Ubiquinone-0) |

|

−130 | [92] | |||

| 1.14 | Coenzyme Q (Ubiquinone) |  |

−230 | ≈ 190 | 70 | [12,75,79,93]] | pKa of SQH• =5.9 pKa of CoQH2 =11.3 (The values of E°′ are estimated in aqueous phase because of the lipophilicity) |

| 1.15 | Mitoquinone |  |

−105 | [94] | (pKa of SQH• = 4.9) | ||

| 1.16 | Plastoquinone |  |

−165 | 55 | 110 | [79,95] | (The values of E°′ have been estimated in aqueous solution because of their lipophilicity) |

| 1.17 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3,6-bis (2-hydroxyethylamino)-1, 4-benzoquinone (BZQ) |

|

−383±10 | [96] | |||

| 1.18 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3,6-bis (carbethoxyamino)-1, 4-benzoquinone (AZQ) |

|

−228±10 −168 |

[96] [97] |

|||

| 2 | 1,2-Dihydroxybenzene | ||||||

| 2.1 | 1,2-Dihydroxybenzene (catechol) |

|

210 | 530 43±5 139±20 98 850 1060 |

370 | [39] [39] [39] [98] [39,98] [39] |

pH 7 pH 13.5 pH ≈ 11 Caln pH 13.5 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

| 2.2 | 2,3-Dihydroxybenzoate |  |

118±5 | [39,99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 2.3 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoate |  |

119±5 | [39,99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 2.4 | 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetate |  |

21 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 2.5 | 3-Hydroxytyramine |  |

18 | [39] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 2.6 | dl-Norepinephrine |  |

44 | [39] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 2.7 | 3,4-Dihydroxycinnamate |  |

84 540 880 1090 |

[39] [98] [98] [98] |

pH 13.5 pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

||

| 2.8 | Adrenalone |  |

~180 | [99,100] | pH 13.5 (pKa of SQH• = 3.6) [13] |

||

| 2.9 |

dl-β-3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine (dl-DOPA) |

|

14 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 3 | 1,3-Dihydroxybenzene | ||||||

| 3.1 | 1,3-Dihydroxybenzene (Resorcinol) |  |

385 810 300±8 304±5 310 720 1130 |

[99] [99] [39] [39] [39] [39] [39] |

pH 13.5 pH 7 pH 13.5 pH 11.6 Caln pH 13.5 Caln pH 7 Caln pH 0 |

||

| 3.2 | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |  |

33 | [98] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 3.3 | 3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |  |

280 | [98] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 3.4 | 3,5-Dihydroxyanisole |  |

840 530 850 1060 |

[98] [98] [98] |

pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

||

| 4 | 1,4-Dihydroxybenzene | ||||||

| 4.1 | 1,4-Dihydroxybenzene-2, 5-disulfonate ion |

|

116 | [101] | pH 12.9 | ||

| 4.2 | Methoxyhydroquinone |  |

−85 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 4.3 | 2,5-Dihydroxyacetophenone |  |

118±10 | [39,99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 4.4 | 2,5-Dihydroxyphenylacetate (Homogentisic acid) |

|

−50 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 4.5 | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoate |  |

33±10 | [39] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 5 | Halogenated quinones | ||||||

| 5.1 | 2,5-Dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

470 | 617 | 544 | [78] | Estimated from the correlation of E(Q/SQ•−) in aqueous buffer and that in MeCN |

| 5.2 | 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloro-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

650 | >650 | [78] | Estimated from the correlation of E(Q/SQ•−) in aqueous buffer and that in |

|

| 5.3 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3,6-bromo-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

32±9 | [82] | |||

| 5.4 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3,6-chloro-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

51±11 | [82] | |||

| 5.5 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3,6-iodo-1, 4-benzoquinone |

|

90±15 | [82] | |||

| 6 | Naphthoquinones | ||||||

| 6.1 | 1,2-Naphthoquinone |  |

68 −89 |

[13] [89] |

iso-propyl alcohol pH 7.8 (pKa of SQH• = 4.8) [13] |

||

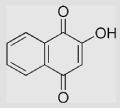

| 6.2 | 1,4-Naphthoquinone |  |

50 −140 |

[13] [89,102] |

iso-propyl alcohol pH 7.8 (pKa of SQH• = 4.1) [13] |

||

| 6.3 | 5-Hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone (juglone) |

|

−93 −95 |

[103] [102] |

|||

| 6.4 | 2-Hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone (lawsone) |

|

−139 −415 |

[13] [102,104] |

iso-propyl alcohol (pKa of SQH• = 4.7) [13] |

||

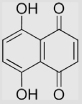

| 6.5 | 5,8-Dihydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−110 | [105] | |||

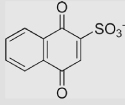

| 6.6 | 1,4-Naphthoquinone-2-sulfonate ion |  |

−60 | 300 | 120 | [79,89] | |

| 6.7 | 2-Methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (Menadione) |

|

−203 −335 |

193 | −5 | [79,102] [106] |

|

| 6.8 | 5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-1, 4-naphthoquinone (Plumbagin) |

|

−156 | [107] | |||

| 6.9 | 2-Hydroxymethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−152 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.10 | 2-(Methoxymethyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−129 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.11 | 2-[(Acetyloxy)methyl]-1, 4-naphthoquinone |

|

−106 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.12 | 2-[[[(2-Chloroethyl)amino] carbonyl]oxy]methyl-1, 4-naphthoquinone |

|

−122 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.13 | 6-(Bromomethyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−92 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.14 | 6-(Chloromethyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−94 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.15 | 6-[(Acetyloxy)methyl]-1, 4-naphthoquinone |

|

−94 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.16 | 6-[[(Methylamino)carbonyl] oxy]methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |

|

−99 | [108] | pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.17 | 2,3-Dimethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−240 | [89,102] | |||

| 6.18 | 2,3-Dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DMNQ) |

|

−240 −183 |

[109] [102] |

|||

| 6.19 | 2,3-Dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−36 | [107] | |||

| 6.20 | 3-Glutathionyl-l,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−132 | [102] | |||

| 6.21 | 3-Glutathionyl-2-methyl-1, 4-naphthoquinone |

|

−192 −195 |

[108] [102] |

pH 7.67 | ||

| 6.22 | 2,3-Diglutathionyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−150 | [110] | |||

| 6.23 | 2-Methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

−170 | 220 | −60 | [79,89,102] | |

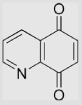

| 6.24 | Quinoline-5,8-dione |  |

−218 | [106] | |||

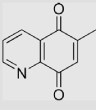

| 6.25 | 6-Methylquinoline-5,8-dione |  |

−279 | [106] | |||

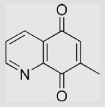

| 6.26 | 7-Methylquinoline-5,8-dione |  |

−282 | [106] | |||

| 6.27 | 6,7-Dimethylquinoline-5,8-dione |  |

−317 | [106] | |||

| 6.28 | Quinoxaline-5,8-dione |  |

−163 | [106] | |||

| 6.29 | 2,3-Dimethylquinoxaline-5,8-dione |  |

−211 | [106] | |||

| 7 | Anthraquinones | ||||||

| 7.1 | 9,10-Anthraquinone |  |

−445 −445 |

[111] [111] |

pH 7 pH 11 (pKa of SQH• = 5.3) [13] |

||

| 7.2 | 1-Hydroxyl-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−385 −415 |

[111] [111] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.3 | 1-Amino-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−435 −480 |

[111] [111] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.4 | 1,4-Dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−249 −304 |

[111,112] [111,112] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.5 | 1-Amino-4-hydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−408 −414 |

[111,113] [111,113] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.6 | 1,4-Diamino-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−410 −424 |

[111,113] [111,113] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.7 | 1,5-Dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−306 −340 |

[111,114] [111,114] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.8 | 1,8-Dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

−325 −405 |

[111,114] [111,114] |

pH 7 pH 11 |

||

| 7.9 | 9,10-Anthraquinone-2-sulfonate ion |  |

−266 −390 −380 |

−76 |

−228 | [13] [115,116] [79] |

iso-propyl alcohol |

| 7.10 | Anthraquinone-1-sulfonate ion |  |

−218 | [13] |

iso-propyl alcohol (p̅Ka of SQH• = 5.4) |

||

| 7.11 | 1,4-Dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone- 2-sulfonate ion |

|

−270 | [117] | |||

| 7.12 | 1,4-Dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone- 6-sulfonate ion |

|

−249 | [117] | |||

| 7.13 | 1,4-Dihydroxy-5,8-bis [(2-hydroxyethylamino) ethyl]amino-9,10-anthraquinone |

|

−527 | [118] | |||

| 7.14 | 1,4-bis[(2-hydroxyethylamino) ethyl]amino-9,10-anthraquinone diacetate |

|

−348 | [97] | |||

| 7.15 | 1,2,5,8-tetrahydroxyanthracene-9, 10-dione (quinalizarin) |

|

73 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

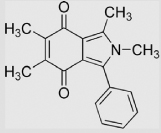

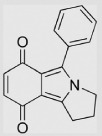

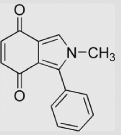

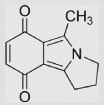

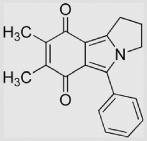

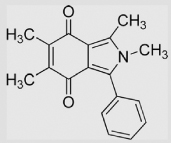

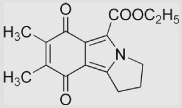

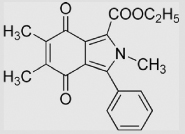

| 8 | Isoindole-4,7-diones | ||||||

| 8.1 | 1,2-Dimethyl- 3-phenylisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−440 | [119] | |||

| 8.2 | 5-Methyl-1, 2-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−420 | [119] | |||

| 8.3 | 1,2,5-Trimethyl-3-phenylisoindole-4, 7-dione |

|

−423 | [120] | |||

| 8.4 | 1-Phenyl-2, 3-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−427 | [120] | |||

| 8.5 | 2-Methyl-3-phenylisoindole-4, 7-dione |

|

−419 | [120] | |||

| 8.6 | 1-Methyl-2, 3-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−438 | [120] | |||

| 8.7 | 5,6-Dimethyl-3-phenyl-1, 2-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−435 | [119] | |||

| 8.8 | 1,2,5,6-Tetramethyl- 3-phenylisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−452 | [119] | |||

| 8.9 | 1-Ethoxycarbonyl-5-methyl-2, 3-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−368 | [119] | |||

| 8.10 | 1-Ethoxycarbonyl-2,5-dimethyl- 3-phenylisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−366 | [119] | |||

| 8.11 | 1-Ethoxycarbonyl-6-methoxy- 5-methyl-2, 3-trimethyleneisoindole-4,7-dione |

|

−383 | [119] | |||

| 8.12 | 1-Ethoxycarbonyl-5-methoxy- 6-methyl-2, 3-trimethyleneisoindole-4, 7-dione |

|

−378 | [119] | |||

| 9 | Miscellaneous | ||||||

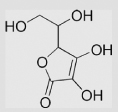

| 9.1 | Ascorbic acid |  |

−175 ≈ −180 |

282 ≈ 300 |

54 ≈ 60 |

[55,121–124] | |

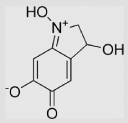

| 9.2 | Adrenochrome |  |

−253 | [97] | |||

| 9.3 | 5-Aminophthalazine-1,4-dione |  |

240 | [125] | pH ≈ 10.6 | ||

| 9.4 | 9,10-Phenanthrenequinone |  |

−124 | [126] | pH 7.8 | ||

| 9.5 | Adriamycin |  |

−292 −328 −341 |

[97] [127] [128] |

|||

| 9.6 | Daunomycin |  |

−305 −341 |

[97] [128] |

|||

| 9.7 | Indigodisulfonate ion |  |

−247 | [129] | |||

| 9.8 | Mitomycin C |  |

−310 | 55 | −368 | [130] | |

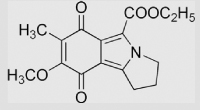

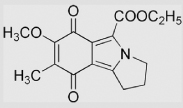

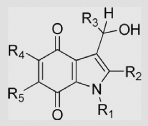

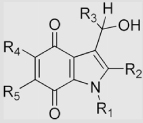

| 9.9 | Indolequinones |  |

[131] | ||||

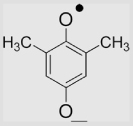

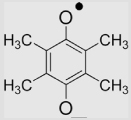

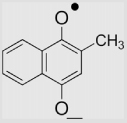

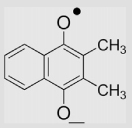

| R1 = CH3, R2 = R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −332±9 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −376±9 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −317±8 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = Morpholino | −365±8 | ||||||

| R1 = CH3, R2 = Ph, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −315±8 | ||||||

| R1 = c-Pr, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −336±5 | ||||||

| R1 = CH2Ph, R2 = C2H5, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −326±3 | ||||||

| R1 = Ph, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −336±5 | ||||||

| R1 = Ph, R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −346±5 | ||||||

| R1 = p-F-C6H4, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −310±4 | ||||||

| R1 = n-Pr, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −318±4 | ||||||

| R1 = n-Pr, R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −324±4 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = R3 = CH3, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −302±9 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = R3 = CH3, R5 = H, R4 = 4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl | −285±5 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = Ph, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −332±9 | ||||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = Thienyl, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −376±9 | ||||||

| R1, R2 = −(CH2)3−, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | −317±8 | ||||||

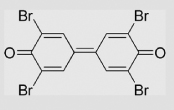

| 9.10 | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetrabromodiphenoquinone |  |

260 | [132] | |||

| 9.11 | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetrachlorodiphenoquinone |  |

260 | [132] | |||

| 9.12 | Methoxatine |  |

−114 | [133] | |||

| 9.13 | 7-Hydroxy-2-[2-(2-hydroxyethyl) aminoethyl]-5-[[2-(2-hydroxyethyl) aminoethyl]amino]-anthra[1,9-cd] pyrazol-6-one |

|

−538 | [134] | |||

| 9.14 | N1-(Acridinyl)-N4-methylsulfonyl- 2-methoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1′, 4′-diimine |

|

85 | [135] | |||

| 9.15 | N1-(Acridinyl)-N4-methylsulfonyl- 2-dimethylaminocyclohexa-2, 5-diene-1′,4′-diimine |

|

−10 | [135] | Ref compound benzoquinone |

||

| 9.16 | 1,2,4-Trihydroxybenzene |  |

−110±20 | [39] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.17 | 1,2,3-Trihydroxybenzene (Pyrogallol)(Pyrogallol) |

|

−9±5 | [39] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.18 | Gallic acid |  |

450 780 980 |

[98] | pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

||

| 9.19 | Methyl gallate |  |

560 910 1120 |

[98,136] 98 98 |

pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

||

| 9.20 | Ethyl gallate |  |

−54 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.21 | 5-Hydroxydopamine |  |

42 | [98] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.22 | Epigallo-o gallate |  |

420 730 930 |

[98] | pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 |

||

| 9.23 | Epigallocatechin gallate |  |

430 | [136] | |||

| 9.24 | Epicatechin |  |

420 48 |

[136] [99] |

pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.25 | (+)-Catechin |  |

570 910 1120 79 |

[98] [98] [98] [99] |

pH 7 pH 3.5 pH 0 pH 13.5 |

||

| 9.26 | Quercetin |  |

330 −37 |

[98] [99] |

pH 13.5 | ||

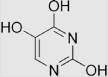

| 9.27 | 2,4,5-trihydroxypyrimidine |  |

132 | [99] | pH 13.5 | ||

| 9.28 | Ellagic acid |  |

187 | [99] | pH 13.5 |

Reduction potentials are at pH 7.0 unless indicated otherwise.

We quote E°′. Many references above provide midpoint potentials. These are nearly the same, typically within 1 mV [40].

Table A2.

Reaction rate constants for SQ•− with dioxygen to form superoxide

| No. | Q or H2Q | SQ•− (or parent Q or H2Q) |

kforward (M−1 s−1) Eq. (7) |

kreverse (M−1 s−1) Eq. (7) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,4-Benzoquinone | 5×104 | 1×109 | [32,137] | |

| 2 | Methyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

1.1×106 | 7.6×108 | [32,137] |

| 3 | 2,3-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

2.4×107 | 4.5×108 | [32,137] |

| 4 | 2,5-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

3.4×106 | 1.7×108 3.6×109 |

[32] [137] |

| 5 | 2,6-Dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone |  |

8.8×106 | 2.2×108 5.8×109 |

[32] |

| 6 | Duroquinone |  |

2.2×108 | 1×107 | [32,138] |

| 7 | 2-Methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (Menadione) |

|

2×108 2.4×108 |

5×106 3.8×107 |

[137] [32] |

| 8 | 2,3-Dimethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone |  |

2×108 | 4×106 | [32,137] |

| 9 | Anthraquinone |  |

5.0×108 | 1.2×104 | [139] |

| 10 | Mitomycin C |  |

2.2(±0.2) ×108 |

1.4×106 | [131] |

| 11 | Adriamycin |  |

3.0(± 0.2) ×108 |

3.8×106 | [131] |

| 12 | 3,5-Dihydroxyanisole |  |

<104 | [136] | |

| 13 | Methyl gallate |  |

2.5×105 | [136] | |

| 14 | Gallic acid |  |

3.4×105 | [136] | |

| 15 | Epigallocatechin (Gallocatechol) |  |

4.1×105 | [136] | |

| 16 | Epicatechin gallate |  |

4.3×105 | [136] | |

| 17 | Epigallocatechin gallate |  |

7.3×105 | [136] | |

| 18 | Epicatechin |  |

6.8×104 | [136] | |

| 19 | Catechin |  |

6.4×104 | [136] | |

| 20 | Indolequinones |  |

[131] | ||

| R1 = CH3, R2 = R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | |||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | |||||

| R1 = R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (4.4±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3,R3 = R5 = H, R4 = Morpholino | (5.2±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1 = CH3, R2 = Ph, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.2±1.2)×108 | ||||

| R1 = CH3, R2 = 4-Ph-C6H4, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (5.1±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1 = CH3, R2 = 2-Naphthyl, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.2±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1 = c-Pr, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.3±0.2)×108 | ||||

| R1 = CH2Ph, R2 = C2H5, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.5±0.3)×108 | ||||

| R1 = Ph, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.3±0.4)×108 | ||||

| R1 = Ph, R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (2.2±0.3)×108 | ||||

| R1 = p-F-C6H4, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.4±0.4)×108 | ||||

| R1 = n-Pr, R2 = CH3, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (4.6±0.5)×108 | ||||

| R1 = n-Pr, R2 = R5 = CH3, R3 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.8±0.6)×108 | ||||

| R1 = R2 = R3 = CH3, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (2.1±0.3)×108 | ||||

| R1 = R2 = R3 = CH3, R5 = H, | (2.4±0.3)×108 | ||||

| R4 = 4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl | |||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = Ph, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (0.9±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = Thienyl, R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (1.1±0.1)×108 | ||||

| R1, R2 = −(CH2)3−, R3 = R5 = H, R4 = OCH3 | (0.9±0.1)×108 | ||||

| (0.8±0.1)×108 | |||||

| 21 | Anisyl-3,4-quinone |  |

≤105 | 8.7×108 | [140] |

| 22 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3, 6-bis (carbethoxyamino)-1, 4-benzoquinone (AZQ) |

|

(1.1±0.1)×107 | (2.7±0.2)×108 | [96] |

| 23 | 2,5-Diaziridinyl-3, 6-bis (2-hydroxyethylamino)-1, 4-benzoquinone (BZQ) |

|

(8.2±0.5)×108 | (1.5±0.1)×105 | [96] |

| 23 | Mitoquinone |  |

(2.9±0.2)×107 | (2.0±0.3)×108 | [94] |

| 24 | Coenzyme Q (Ubiquinone) |  |

2×108 | 5×106 | [75,137] |

Footnotes

A standard half-cell reduction potential (E°) indicates that it was measured under standard conditions: 25 °C, 1.0 M concentration for each species participating in the reaction, pH 0.0 when in aqueous solution; a partial pressure of 100 kPa (0.986 atm) for each gas that is part of the reaction, and metals in their pure state. The superscript ° on the E implies these standard conditions. Standard reduction potentials are relative to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), a reference electrode that is given a value of 0.00 V at all temperatures. Historically, some countries including the United States and Canada used standard oxidation potentials rather than reduction potentials in their calculations. These are simply the negative of standard reduction potentials. However, the term "redox potential" is widely used; this results in much confusion because it is not clear if a reduction or oxidation potential is being referred to. In modern chemistry texts all potentials quoted are reduction potentials. In the field of redox biology we suggest that this convention be adopted to eliminate possible confusion. E°′ is widely used to indicate that the pH is 7.0, rather than 0.0.

The notations Q/SQ•− and SQ•−,2H+/H2Q represent the reactions of Eqs. (1) and (2). If in an electrochemical cell, then the slash (/) would represent the electrode of the cell.

The word “relatively” is used here because the reference is the standard hydrogen electrode, E°′ = 0 mV.

References

- 1.Krueger FR, Werther W, Kissel J, Schmidt ER. Assignment of quinone derivatives as the main compound class composing ‘interstellar’ grains based on both polarity ions detected by the ‘Cometary and Interstellar Dust Analyser’ (CIDA) onboard the spacecraft STARDUST. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:103–111. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trumpower BL. The protonmotive Q cycle. Energy transduction by coupling of proton translocation to electron transfer by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:11409–11412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stocker R, Bowry VW, Frei B. Ubiquinol-10 protects human low density lipoprotein more efficiently against lipid peroxidation than does alphatocopherol. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:1646–1650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiemann R, Renger G, Gräber P, Witt HT. The plastoquinone pool as possible hydrogen pump in photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;546:498–519. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(79)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odom AL, Hatwig CA, Stanley JS, Benson AM. Biochemical determinants of Adriamycin toxicity in mouse liver, heart and intestine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43(4):831–836. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90250-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers CE, McGuire WP, Liss RH, Ifrim I, Grotzinger K, Young RC. Adriamycin: the role of lipid peroxidation in cardiac toxicity and tumor response. Science. 1977;197(4299):165–167. doi: 10.1126/science.877547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalyanaraman B, Morehouse KM, Mason RP. An electron paramagnetic resonance study of the interactions between the adriamycin semiquinone, hydrogen peroxide, iron-chelators, and radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991;286(1):164–170. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90023-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;20(7):933–956. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36(7):838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komori A, Yatsunami J, Okabe S, Abe S, Hara K, Suganuma M, Kim SJ, Fujiki H. Anticarcinogenic activity of green tea polyphenols. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 1993;23:186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishop CA, Tong LKJ. Equilibria of substituted semiquinones at high pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:501–505. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rich PR, Bendall DS. The kinetics and thermodynamics of the reduction of cytochrome c by substituted p-benzoquinols in solution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1980;592:506–518. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao PS, Hayon E. Ionization constants and spectral characteristics of some semiquinone radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1973;77:2274–2276. [Google Scholar]