Abstract

Opportunities to investigate selection in free-living species during a naturally occurring epidemic are rare; however, we assessed innate immunocompetence in Florida scrub-jays before the population suffered the greatest over-winter mortality in 20 years of study. Propitiously, three months prior to the epidemic, we had sampled a number of male breeders to evaluate a suite of physiological measures that are commonly used to estimate the overall health-state of an individual. There was a significant, positive selection gradient for both Escherichia coli bacterial killing capability and body condition, suggesting that directional selection had occurred upon each of these traits during the disease epidemic.

Keywords: Aphelocoma coerulescens, ecoimmunology, directional selection

1. Introduction

An individual's ability to survive disease should be correlated with their immunocompetence and thus it is often assumed that greater measures of immunocompetence generally indicate greater immunity (for review see Ardia & Schat 2008). Although many studies have investigated the relationship between survival and immune response through immune challenges (see review by Møller & Saino 2004), a missing component is evidence of resistance against a naturally occurring disease. Our understanding of the relationship between immunity to a pathogen and survival is complicated, because immune capability can vary with overall body condition (Ardia & Schat 2008), reproductive state or effort (Sheldon & Verhulst 1996) and physiological stress (for review see Sapolsky et al. 2000).

Other studies have examined traits favoured by selection during catastrophic events; however, none have implicated a pathogen outbreak as the cause (e.g. Bumpus 1899; Price & Grant 1984). More recently, Nolan et al. (1998) found that smaller house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) were more likely to survive an outbreak of mycoplasmal conjunctivitis. Here we report, for the first time in birds, directional selection on an immunocompetence trait during an epidemic.

Between July 2008 and January 2009, 39 per cent of our study population of Florida scrub-jays died. This is more than twice the annual mortality rate (long-term average of approximately 18 per cent; Woolfenden & Fitzpatrick 1984). Although we do not know the exact time-course of all fatalities, many died between mid-July and October and this was almost certainly a consequence of a disease epidemic. As part of a project on breeding male Florida scrub-jays, we had collected data three months prior to the epidemic. These data, bacterial killing ability (BKA), body condition, baseline levels of the avian stress hormone, corticosterone (CORT), and reproductive effort for 32 breeding males, allowed us to determine whether measures of constitutive immune response, body condition, stress or reproductive effort were subject to selection during this epidemic.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study species and location

Our study population of Florida scrub-jays occupies the southern part of Archbold Biological Station in Florida (27°10′50″ N, 81°21′00″ W). All birds are identifiable by unique colour and United States Fish and Wildlife Service numbered aluminum ring combinations.

(b). Capture and blood sampling

Four days following hatching of its clutch, we used Potter traps to capture that territory's male breeder. We then collected a small blood sample from the brachial vein within 2 min to measure baseline CORT levels (Romero & Reed 2005). Subsequently, we collected a sterile blood sample and 40 µl was transferred to a vial containing 400 µl of CO2-independent media (catalog #18045: GIBCO Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 4 mM l-glutamine (Sigma, #G-6392) for use in an in vitro BKA (see below). Blood samples were kept on ice until return to the laboratory (less than 60 min). Microhaematocrit tubes containing samples for measurement of baseline CORT levels were centrifuged and plasma was frozen and stored at −20°C until radioimmunoassay (RIA).

(c). Bacterial killing assay

We followed the protocol of Millet et al. (2007) to assay Escherichia coli (ATCC #8739) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC #6538; Microbiologics, St Cloud, MN) killing ability. An 110 µl suspension of bacteria and diluted blood was incubated in a heat-block at 41°C (based upon average passerine body temperature; Gill 2007) for 20 min to stimulate an immune response. Two 50 µl aliquots were spread onto separate trypticase soy agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. Controls consisted of 10 µl of the reconstituted bacterial culture diluted in 100 µl of media. Colonies were counted 24 h later and bactericidal activity was calculated as the proportion of bacterial colonies killed in samples when compared to controls. A nearly identical procedure that differed only in incubation time (60 min) was then used to determine the ability of blood to kill S. aureus.

(d). Radioimmunoassay

We measured plasma CORT concentrations with a single direct RIA. The RIA used tritiated CORT from PerkinElmer, Inc. (Boston, MA) and CORT antiserum from Esoterix Inc. (Calabasas, CA). The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 16 per cent. CORT values were not normally distributed; therefore, data were square root transformed. For RIA details, see Schoech et al. (1997).

(e). Body condition index

As per the methods of Green (2001), we derived a body condition index (BCI) using a principal component analysis of structural measures (head breadth and the lengths of the head-plus-bill, wing cord, tail and tarsus). PC1 (variance explained = 0.57) was regressed upon body mass and the resultant residuals served as the BCI.

(f). Paternal effort

Both the incubation and nestling stages average 18 days, and fledglings reach nutritional independence at 70 days-of-age (Woolfenden & Fitzpatrick 1984). We estimated paternal effort by summing the total days that a breeding male cared for offspring, corrected for the number of offspring. If we did not know the exact date of either nest failure or of the death of dependent young, we used an estimate based upon the last observation.

(g). Statistical analysis

Because the disease outbreak occurred three months after most data were collected, we used data for E. coli killing and BCIs from multiple captures at different times to determine repeatability (interclass correlation coefficient; Lessells & Boag 1987). We could not assess repeatability for S. aureus BKA as we had only 32 captures, each of different birds, from 2008. Escherichia coli BKA was highly repeatable within individual males (r = 0.825, F13,52 = 4.296, p = 0.003) as was BCI (r = 0.640, F15,54 = 2.243, p = 0.043), thus, immunocompetence and body condition at the time of sampling could reflect those at the time of the outbreak.

Data were standardized by dividing all values by the standard deviation (Lande & Arnold 1983; Grant & Grant 1995) prior to selection analysis. The selection differential (S, the net effect of selection on a trait) was calculated as the difference between the mean value of the trait in all birds sampled and the mean value of the trait in only the survivors. We used t-tests to assess statistical significance of the selection differential. We also calculated the direct effect of selection on each trait, or selection gradient (β), by estimating the partial regression coefficient of relative fitness (survival) on each trait. We used a logistic regression analysis (Grant & Grant 1995) to assess significance of the selection gradients (dead = 0 and alive = 1 in all analyses). The variables considered included the two measures of immune function (BKA of E. coli and S. aureus), baseline CORT levels, BCI, age and paternal effort (see above). All statistical analyses were conducted in PASW v. 17.0 (PASW Statistics 2009).

3. Results

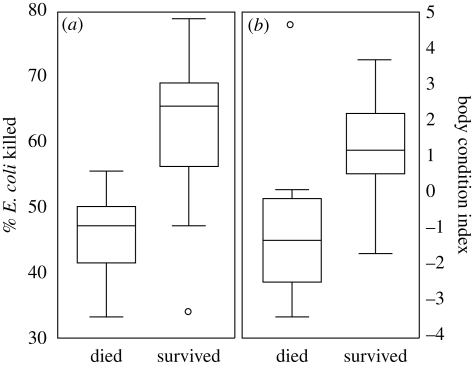

There was a significant selection gradient for both E. coli killing ability and BCI (increased E. coli BKA and greater body condition), suggesting that selection was acting on these traits (table 1; figure 1). No other traits showed statistically significant selection differentials or selection gradients during this selection event (table 1). Even though a selection gradient was found, there was no net effect of selection on any candidate trait, as evidenced by no significant difference in the means of any of our measures between individuals that were alive before or after the epidemic (see table 1 for selection differential values).

Table 1.

Net and directional natural selection on male Florida scrub-jays throughout an epidemic in 2008. Coefficients in boldface are significantly different (p < 0.05) from zero. S is the selection differential, β is the selection gradient from a linear regression analysis, power represents the sample size necessary to have found significant results in each of these measures given the differences among individuals.

| selection differential |

selection gradient |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | p | power | β | s.e. | p | |

| E. coli BKA | +0.374 | 0.155 | 38 | 0.110 | 0.042 | 0.008 |

| S. aureus BKA | +0.145 | 0.617 | 82 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 0.193 |

| baseline CORT | −0.249 | 0.584 | 44 | −0.721 | 0.546 | 0.182 |

| body condition | +0.356 | 0.152 | 38 | 0.986 | 0.370 | 0.001 |

| age | +0.030 | 0.915 | 500 | 0.046 | 0.170 | 0.361 |

| parental effort | −0.016 | 0.951 | 520 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.762 |

| sample size | 32 | 32 | ||||

Figure 1.

(a) Variation in E. coli bacterial killing and (b) body condition (BCI) as a function of survival (0 = dead, 1 = alive), represented as a box (25th and 75th percentiles with median line) and whisker (1.5× interquartile range or max value if less) plot.

4. Discussion

We provide evidence that this disease outbreak led to directional selection on both E. coli killing ability (a measure of non-specific constitutive immunity) and body condition. Although we did not discern a significant net change in these traits after the epidemic, we only have comprehensive data from male breeders in the population that were feeding young (of which nine of 32 died; 28%) and know little about the health-state of females or young-of-the-year (a demographic that suffered 51% mortality). Further, a power analysis shows that (for some measures) only a slightly larger sample size could have revealed significant net selection (see table 1). Also, a screening of survivors showed that 75% had antibodies against eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), strongly suggesting that this pathogen was responsible for the epidemic (R. K. Boughton unpublished data). For perspective, in previous years EEE antibody prevalence was approximately 10 per cent (R. K. Boughton unpublished data).

At the time of data collection a male breeder must provision his mate and offspring at the nest, while defending their territory. The demands remain elevated until the young reach nutritional independence. We speculate that the coincidence of high parental effort with the disease outbreak contributed to the impact of the pathogen upon our study population. Obviously, there are multiple other factors that are not considered here, such as additional components of the immune system (Martin et al. 2006; Ardia & Schat 2008) and genetic quality (O'Brien & Evermann 1988) that could have contributed to survival.

Though speculative, there are a number of possible reasons that we found directional selection in only one of two measures of innate immunity. First, in a comparative study with birds, Millet et al. (2007) found differences between BKA of S. aureus and E. coli within the same individuals. Differences that may be due to immunoredistribution (a temporary shifting of immune resources and function to different components of the immune system; Martin et al. 2006), the effectiveness or efficiency of toll-like receptors specific for each E. coli and S. aureus (Janeway & Medzhitov 2002), or a population-wide difference in exposure history to these bacteria (Keeler et al. 2007). It is also important to note, that although there was no statistically significant directional selection for S. aureus killing, the individuals that survived did have slightly greater S. aureus killing ability (table 1).

Our findings that link an aspect of immunocompetence with survival agree with those of other studies (reviewed in Møller & Saino 2004). Though used extensively in current ecoimmunology research, the BKA we used (see Millet et al. 2007) has not been linked to fitness in free-living animals. Our results confirm that these measures can be indicators of individual quality and fitness, and support the findings of other avian studies (i.e. Råberg & Stjernman 2003; Hanssen et al. 2004) in that physiological condition during one life-history stage can carry over and influence survival during other life-history stages.

Acknowledgements

All methods were approved by the University of Memphis IACUC.

We thank the personnel of Archbold Biological Station, particularly R. Bowman. We also thank M. A. Rensel and G. M. Morgan. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (IBN-0346328 to S.J.S., IOS-0909620 to S.J.S. & T.E.W., & SGER-0855879 to R.K.B.), and a Van Vleet Memorial Fellowship (to T.E.W. from the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Memphis). We also thank three anonymous reviewers for comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- Ardia D. R., Schat K. A.2008Ecoimmunology. In The immunology of birds (eds Davison F., Kaspers B., Schat K. A.). Cambridge, MA: Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- Bumpus H. C.1899The elimination of the unfit as illustrated by the introduced house sparrow Passer domesticus. Biol. Lect., Mar. Biol. Lab. Woods Hole, 209–226 [Google Scholar]

- Gill F. B.2007Ornithology, 3rd edn.New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Company [Google Scholar]

- Grant P. R., Grant B. R.1995Predicting microevolutionary responses to directional selection on heritable variation. Evolution 49, 241–251 (doi:10.2307/2410334) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A. J.2001Mass/length residuals: measures of body condition or generators of spurious results? Ecology 82, 1473–1483 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[1473:MLRMOB]2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen S. A., Hasselquist D., Folstad I., Erikstad K. E.2004Costs of immunity: immune responsiveness reduces survival in a vertebrate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 271, 925–930 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C. A., Medzhitov R.2002Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 197–216 (doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeler C. L., Bliss T. W., Lavri M., Maughan M. N.2007A functional genomics approach to the study of avian innate immunity. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 117, 139–145 (doi:10.1159/000103174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R., Arnold S. J.1983The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution 27, 1210–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessells C. M., Boag P. T.1987Unrepeatable repeatabilities: a common mistake. Auk 104, 116–121 [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. B., Weil Z. M., Nelson R. J.2006Refining approaches and diversifying directions in ecoimmunology. Integr. Comp. Biol. 46, 1030–1039 (doi:10.1093/icb/icl039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet S., Bennett J., Lee K. A., Hau M., Klasing K. C.2007Quantifying and comparing constitutive immunity across avian species. Dev. Comp. Immun. 31, 188–201 (doi:10.1016/j.dci.2006.05.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A. P., Saino N.2004Immune response and survival. Oikos 104, 299–304 (doi:10.1016/j.dci.2006.05.013) [Google Scholar]

- Nolan P. M., Hill G. E., Stoehr A. M.1998Sex, size and plumage redness predict house finch survival in an epidemic. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 265, 961–965 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0384) [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien S. J., Evermann J. F.1988Interactive influence of infectious disease and genetic diversity in natural populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 254–259 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(88)90058-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASW Statistics 2009PASW statistics version 17.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS, Inc [Google Scholar]

- Price T. D., Grant P. R.1984Life-history traits and natural selection for small body size in a population of Darwin finches. Evolution 38, 483–494 (doi:10.2307/2408698) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Råberg L., Stjernman M.2003Natural selection on immune responsiveness in blue tits Parus caeruleus. Evolution 57, 1670–1678 (doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1287-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L. M., Reed J. M.2005Collecting baseline corticosterone samples in the field: is under three minutes good enough? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 140, 73–79 (doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2004.11.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R. M., Romero L. M., Munck A. U.2000How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr. Rev. 21, 55–89 (doi:10.1210/er.21.1.55) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoech S. J., Mumme R. L., Wingfield J. C.1997Breeding status, corticosterone, and body mass in the cooperatively breeding Florida scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens). Physiol. Zool. 70, 68–73 (doi:10.1086/639545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon B. C., Verhulst S.1996Ecological immunology: costly parasite defences and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 317–321 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10039-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfenden G. E., Fitzpatrick J. W.1984The Florida scrub jay, demography of a cooperative-breeding bird. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University [Google Scholar]