Abstract

Repetitive sequences in eukaryotic genomes induce chromatin-mediated gene-silencing of juxtaposed genes. Many components that promote or antagonize silencing have been identified, but how heterochromatin causes variegated and heritable changes in gene expression remains mysterious. We have used inducible mis-expression in the Drosophila eye to recover new factors that alter silencing caused by the bwD allele, an insertion of repetitive satellite DNA that silences a bw+ allele on the homologous chromosome. Inducible modifiers allow perturbation of silencing at different times in development, and distinguish factors that affect establishment or maintenance of silencing. We find that diverse chromatin and RNA processing factors can de-repress silencing. Most factors are effective even in differentiated cells, implying that silent chromatin remains plastic. However, over-expression of the bantam microRNA or the crooked-legs (crol) zinc-finger protein only de-repress silencing when expressed in cycling cells. Over-expression of crol accelerates the cell cycle, and this is required for de-repression of silencing. Strikingly, continual over-expression of crol converts the speckled variegation pattern of bwD into sectored variegation, where de-repression is stably inherited through mitotic divisions. Over-expression of crol establishes an open chromatin state, but the factor is not needed to maintain this state. Our analysis reveals that active chromatin states can be efficiently inherited through cell divisions, with implications for the stable maintenance of gene expression patterns through development.

Author Summary

Repetitive DNA and transposons are compacted into heterochromatin in eukaryotic genomes to silence potentially dangerous elements. Heterochromatic silencing is distinct from classical gene repression because affected genes randomly switch on and off during development, with varying degrees of somatic heritability. Here, we focus on the silencing of a reporter gene by a repetitive DNA satellite block on a homologous chromosome. Silencing in this system relies on long-range chromosomal interactions, but these are disrupted during mitosis and must be re-established every cell cycle. We employed an inducible system to identify factors that can alter silencing when over-expressed. The inducible nature of this system allows us to perturb silencing at different development stages, and distinguish factors that affect the establishment or maintenance of silencing. We identified a diverse collection of modifiers, and most can alter silenced chromatin even in differentiating cells. Strikingly, over-expression of one factor – the crol zinc-finger protein – establishes a de-repressed state that is somatically heritable. Our analysis of crol implicates cell cycle progression in the maintenance of silenced chromatin, and argues that active chromatin can be efficiently propagated through mitotic divisions. Our findings validate inducible modifiers as tools for the dissection of establishment and maintenance of chromatin states.

Introduction

Eukaryotic DNA is packaged with histones into nucleosomes, which represent the primary unit of chromatin. Nucleosomes render DNA inaccessible to transcription factors, and thus modulate transcriptional activity. Nucleosome stability is governed by chromatin remodeling complexes that move histones with respect to the DNA [1] as well as the physical properties of the sequences the histones wrap [2]. Chemical modifications of histone tails are also important for chromatin transactions, as they affect how nucleosomes interact with each other, recruit auxiliary factors, and define functional chromatin domains [3]. Chromatin can be separated into two types – euchromatin, where most unique genes are found, and heterochromatin, rich in transposable elements and repetitive sequences. While a great deal is known about the different protein composition and signature chemical modifications of these two types of chromatin environments, how they are established and maintained remains mysterious.

Much of our understanding of heterochromatin comes from genetic screens performed with variegating reporter genes in Drosophila. These genetics studies have focused on the repressive effects that heterochromatin exerts on euchromatin when the two are in close proximity, and have identified a number of chromatin factors required for efficient silencing [4], [5]. Molecularly, heterochromatin-mediated silencing is correlated with repressive histone modifications and the association of heterochromatic proteins [6]. Silenced genes exhibit reduced accessibility of restriction enzymes and highly regular nucleosomal arrays, further indicating that repression is achieved through an altered chromatin structure [7]. A silent chromatin state can be established at euchromatin de novo by the artificial tethering of heterochromatin factors to a site [8], [9]. However, it remains unknown what the requirements are for the propagation of an altered chromatin state through DNA replication and cell division.

Here we use the GAL4-UAS over-expression system [10] to perturb chromatin-mediated silencing. Our analysis reveals a more extensive array of modifiers than previously appreciated. We exploited the modular nature of the GAL4-UAS system to address the establishment and maintenance of heterochromatic silencing in cycling and differentiated cells. Our findings indicate that active chromatin states can be established early in development and stably inherited through mitosis, while silenced chromatin is plastic and must be re-enforced every cell cycle.

Results

The brownDominant (bwD) allele is an insertion of ∼2 Mb of satellite sequence in the brown gene, and confers a heterochromatic chromatin structure to the locus [11]. This insertion causes dominant heterochromatic gene-silencing in bwD/bw+ heterozygous adults, so that only ∼5% of eye cells are pigmented [12]. Silencing of the bw+ allele proceeds through a sequence of chromosomal interactions, where the bwD allele first somatically pairs with bw+, and then the aggregation of repetitive sequences within the nucleus drags the locus into the heterochromatic chromocenter (Figure 1A; [13]). These interactions are required for silencing of the bw+ gene [14]. Pairing and aggregation are thought to be disrupted every mitosis and frequently reform in each interphase, accounting for the speckled variegation of bw+ silencing in the adult eye [15], [16]. The severity of silencing with bwD is reliable and consistent between individuals, and we therefore used this system in a screen to recover genes that perturb bwD silencing when over-expressed.

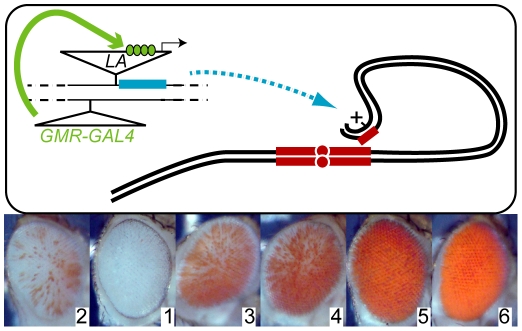

Figure 1. A perturbation screen for bwD–mediated heterochromatic silencing.

(A) New insertions of a P[LA] transposon carrying a y+ marker and a GAL4-inducible promoter were recovered in progeny that also carried a eye-specific GAL4 driver (GMRGAL) and the bwD heterochromatic insertion (small red block). GAL4 (green) activates a inducible promoter in the P[LA] insertion and transcribes any neighboring gene (blue). Somatic pairing between homologous chromosomes (black lines) and aggregation of heterochromatin (red blocks) normally efficiently silences the paired bw+ eye color gene. We screened for new P[LA] insertions that altered bwD silencing, and identified the position of the P element by iPCR. (B) Silencing of bw+ was ranked on a scale from 1 to 6. Normal bwD/bw+ silencing was scored as Rank 2, enhancement as Rank 1, and increasing degrees of de-repression as Ranks 3–6. Representative eyes from each rank are shown.

Diverse factors modify heterochromatic gene-silencing

We used the modular GAL4-UAS mis-expression system [10] to identify endogenous genes that could modify the severity of bwD silencing when over-expressed in the eye (Figure 1A). We mobilized the mis-expression transposons P[EP] and P[LA], both of which contain a GAL4-dependent promoter at one end of the element that transcribes into flanking DNA sequences [10], [17]. New insertions were combined with the eye-specific GAL4 source GMRGAL and bwD to test for effects on heterochromatic silencing, and adults with increased or decreased eye color were retained. We categorized pigmentation of the eye on a scale of 1 through 6, where silencing from the bwD allele with no mis-expression insertion was assigned a score of 2, and full pigmentation in bw+ adults was a score of 6 (Figure 1B). Insertions with enhanced silencing were assigned a score of 1, and insertions with de-repressed silencing were ranked 3–6 depending on the extent of de-repression.

We recovered 28 P[EP] modifying insertion lines and 23 P[LA] insertion lines from ∼1100 fertile individual crosses (Table 1). 45 lines showed de-repression of silencing, and 9 lines showed enhanced silencing. 7 of these lines had effects on eye morphology, but changes in silencing were clear even in these cases where the eye was rough. We used inverse PCR to identify the location of the transposon in each line (Table S1). A single gene could not be identified in most P[EP] lines as multiple insertions were present, in part because these lines still carried the donor insertion. The 4 lines with single insertions that could be identified were retained (Table 1; Table S1), and other lines discarded. Inverse PCR successfully identified 22 of the P[LA] insertions. We also tested candidate over-expression lines from public stock centers that we selected based on molecular pathways known to be involved in heterochromatic gene-silencing, or implicated by hits in our screens (Table 1; Table S2). Each line was verified as requiring GAL4 induction of the flanking genomic sequence for effects on bwD silencing.

Table 1. Over-expression of genes with effects on silencing.

| linea | CG IDb | gene | bwD/bw+ silencingc | description | |||

| GMRGAL4 | eyGAL4 | A5CGAL4 | GMR-wIR d | ||||

| EPChd12 | CG3733 | Chd1 | 1 | 2 | viableg | ++ | chromatin remodeler |

| XPd10097 | CG31212 | Ino80 | 1 | 1 | viable | +++ | chromatin remodeler |

| LA77A | CG1507 | pur-alpha | 1e | 2 | viableg | ++ | transcription factor |

| LA4.5 | CG11844 | vig2 | 1 | 3 | lethalh | ++ | mRNA-binding |

| LA4.4 | CG10630 | CG10630 | 1 | 2 | lethal | ++ | mRNA-binding |

| LA3.2 | CG8036 | CG8036 | 1 | 2 | viable | ++ | transketolase |

| LA3.1 | CG11352 | Jim | 1 | 2 | lethal | ++ | zinc-finger protein |

| LA5.3 | CG5486 | Ubp64E | 1 | 2 | lethal | ++ | ubiquitin protease |

| LAE154 | CG31868 | Samuel | 1e | 2 | lethalh | ++ | steroid nuclear receptor |

| LA11A | CG2368 | psq | 1e | 2f | lethal | ++ | transcription factor |

| no insertion control | – | 2 | 2 | viable | ++ | – | |

| LA2.1 | Bte00003 | Doc | 3e | lethal | lethal | ++ | retrotransposon |

| LA1.4 | CG8676 | HR39 | 3 | 2e | lethal | ++ | steroid nuclear receptor |

| EP701 | CG5899 | Etl1 | 3 | 2 | viable | n.d. | chromatin remodeler |

| EY12846 | CG3696 | kismet | 3 | 2 | viable | ++ | chromatin remodeler |

| LA4.3 | CG3696 | kismet | 3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | chromatin remodeler |

| LAS146 | CG6930 | l(3)neo38 | 3 | 2 | lethal | ++ | zinc-finger protein |

| LA2.4 | CG7757 | CG7757 | 3 | 2 | lethalh | ++ | small nuclear riboprotein |

| LAS110 | * | * | 3 | 2 | viableg | ++ | * |

| LA1.3 | CG5933 | MTA70 | 3 | 2 | viable | ++ | RNA methyltransferase |

| LAJJ2A | CG14938 | crol | 3e | 2/6i | lethal | ++ | zinc-finger protein |

| EY09290 | CG9537 | DLP | 4 | 2 | lethal | ++ | transcription factor |

| EY04120 | CG2031 | Hpr1 | 4 | 2 | viable | ++ | mRNA export factor |

| LAS55 | CR33559 | bantam | 4e | lethal | lethalh | ++ | microRNA |

| LA2.5 | CR33559 | bantam | 4e | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | microRNA |

| LA1.6 | CG3162 | CG3162 | 4 | 2 | lethal | ++ | small nuclear riboprotein |

| EY06795 | CG10279 | Rm62 | 4 | 2 | viable | + | RNA helicase |

| EY03252 | CG32438 | SMC5 | 4 | 2 | viable | n.d. | condensin |

| LA00872 | CG9383 | Asf1 | 4 | lethal | lethal | n.d. | histone chaperone |

| XPd04051 | CG8989 | His3.3B | 4 | 2 | viable | n.d. | histone variant |

| EY23248 | CG17921 | HmgZ | 4 | 3 | viable | + | high mobility group protein |

| EY03609 | CG17950 | HmgD | 5 | 2 | lethalh | + | high mobility group protein |

| LA3.4 | CG5794 | CG5794 | 5 | 2 | viable | ++ | ubiquitin protease |

| EP635 | CG4548 | xnp | 5 | 4 | lethal | ++ | chromatin remodeler |

| EY08629 | CG1966 | Acf1 | 6 | 3 | viable | + | chromatin assembly factor |

| EY10737 | CG33182 | CG33182 | 6 | 2 | viable | n.d. | histone demethylase |

| EP14C | CG13895 | CG13895 | 6 | 2 | viable | ++ | CENPB motifs |

| LA4.1 | CG3941 | pita | 6 | 2 | viable | ++ | zinc-finger protein |

| EPDJ1 | CG12819 | sle | 6 | 2 | viable | ++ | nucleolar protein |

| EP27 | CG13109 | tai | 6 | 2e | lethal | +++ | transcription factor |

| EP13 | CG5935 | Dek | 6 | 2 | viableg | ++ | chromatin & splicing factor |

– Bold, lines recovered in screens; non-bold, candidate lines.

– * an genomic insertion site was not identified by iPCR.

– severity of silencing was scored in ranks from severe silencing (1) to no silencing (6).

– eye color after w+ knockdown ('++' amount in controls, '+++' increased, '+' reduced).

– rough eyes.

– small eyes.

– lethal in males.

– pupal lethal.

– sectors of complete de-repression in a speckled background.

Altogether, we identified 36 genes that act as over-expression modifiers of bwD. These include 7 genes that are known to be required for heterochromatic gene-silencing from previous studies with null alleles (psq [18], Ubp64E [19], ASF1 [20], Acf1 [21], xnp [22], [23], Rm62 [24], and vig2 [25]). Some of these factors have also been implicated in Polycomb-dependent silencing, suggesting that this screen may identify factors that can affect multiple levels of chromatin structure and gene expression. As these factors affect silencing when over-expressed, caution is necessary in inferring their normal functions. Indeed, we noted that in many cases over-expression of a factor had similar effects on silencing as null alleles for that factor, suggesting that their effect is not simply due to increased dosage of the factor. We group these factors according to their annotated biological function below.

Chromatin factors

A diverse collection of chromatin factors affects bwD silencing. We recovered insertions that over-express structural components of chromatin (SMC5, HmgZ, HmgD, and His3.3B). HmgZ, HmgD, and H3.3 are enriched in active chromatin [26], [27], and might promote the activation of genes when over-expressed. SMC5 has been implicated in both compaction of chromatin and in long-range enhancer-promoter interactions during gene activation. Structural components of chromatin are believed to be important for connections between nucleosomes [28]. A second set of chromatin factors implicates nucleosome assembly and remodeling (the remodelers Chd1, Ino80, Etl1, Kismet, and XNP; the histone chaperones ASF1 and Dek; the chromatin assembly factor ACF1). It is striking that individual remodelers have distinctive effects on silencing, presumably by altering nucleosome dynamics at specific sites in the genome [22]. Finally, we identified one gene with histone modifying activity – the histone JmjC demethylase Kdm4B. This demethylase removes methylation from both histone H3-K9 and H3-K36 residues [29], [30]. The insertion Kdm4BEY10737 partially de-represses silencing on its own, but bwD is further de-repressed with GMRGAL induction.

Transcription factors

Previous studies have identified mutations in genes encoding transcription factors as modifiers of heterochromatic silencing [31]. These mutations are thought to affect the competition between activation and repression at genes juxtaposed to heterochromatin, thereby enhancing silencing. We identified 10 genes annotated as transcription factors that alter bwD silencing when over-expressed. Over-expression of HR39, l(3)neo38, crol, DLP, CG13895, pita, Dek, and tai de-repress silencing, consistent with the idea that excess production of these factors may overcome repressive effects of heterochromatin. In contrast, over-expression of the psq, pur-alpha Jim, and Samuel transcription factors enhance silencing. We noted that a number of the recovered factors (Samuel, HR39, crol, tai, and Dek) are linked to ecdysone hormone-triggered developmental responses. The levels of these proteins change during development, and this suggests that ecdysone responses stimulate global change in heterochromatin. A developmentally-regulated aspect of heterochromatic silencing has been previously suggested from patterns of silencing of a HS-lacZ gene [32], [33].

RNA processing factors

This group of modifiers includes RNA binding and export factors (vig2, Hpr1, Rm62, sle, CG10630), an RNA modification enzyme (MTA70), and splicing components (CG7757, CG3162, Dek). The vig2 and Rm62 genes have been previously identified as involved in heterochromatic silencing [25], [24]. Our recovery of splicing factors and RNA modifying enzymes implicates additional aspects of RNA metabolism in silencing.

Miscellaneous factors

Some factors we identified have domains that only partially identify their functions. We identified the transketolase CG8036, and 2 ubiquitin-dependent proteases (Ubp64E, CG5794). Ubp64E has been previously identified as a modifier of silencing, and may modulate the stability of chromatin proteins after ubiquitinylation [19]. Other factors may also act by modifying heterochromatin proteins.

Two remaining factors were surprising because the recovered insertion sites did not map near annotated protein-coding genes. The insertion P[LA]S55 lies at position 638208 of chromosome 3L, and P[LA]2.5 lies nearby at position 639482. Both insertions are upstream of the bantam microRNA precursor gene (4 Kb and 2.5 Kb, respectively) and oriented so that GAL4 induction may over-produce this transcript. These insertions appear to generate functional bantam microRNAs, because induction by GMRGAL produces enlarged eyes in adults, consistent with the role of bantam in promoting cell division and growth [34]. A third insertion – P[LA]2.1 – lies in the 5′ UTR of a Doc retrotransposon and maps to the second chromosome. This insertion is oriented to over-produce the Doc transcript. However, induction of P[LA]2.1 probably produces a transcript from an unidentified gene downstream of the Doc insertion, because other mis-expression insertions in selected Doc elements do not recapitulate the phenotype of P[LA]2.1 (data not shown).

Specificity of over-expression for heterochromatic rearrangements

We tested our insertions with a series of additional assays. We first determined if over-expression modifiers have general effects on heterochromatic silencing, or are limited to bwD-mediated silencing. As an independent test of silencing, we used the inversion In(1)wm4 (wm4) where the w+ gene is juxtaposed to pericentric heterochromatin. Many mis-expression constructs carry a w+ marker and cannot be assayed with wm4. However, the P[LA] element we used is marked with y+; thus we could induce our lines using GMRGAL in combination with wm4 and then assess effects on white silencing. We found that all 8 enhancers of bwD silencing are also enhancers of wm4 silencing (Table 2). This implies that these factors do indeed have general effects on heterochromatin. The effects of bwD de-repressors are more variable. Only 1 line de-represses both bwD and wm4, and 9 lines have no effect on wm4. Surprisingly, 2 lines de-repress bwD but enhance wm4. Previous studies have also found that the bwD and wm4 rearrangements are not equivalently affected by all modifiers of heterochromatic silencing [35]. These differences suggest that each chromosome rearrangement has a unique combination of gene regulatory elements and heterochromatic sequences that determine the extent of silencing. The testing of bwD modifiers for effects on silencing of wm4 is informative, as it reveals that enhancers are general, yet de-repressors are not. The silencing of bw+ by bwD provides a sensitive assay for multiple levels of chromosomal organization. Over-expression lines that perturb bwD silencing yet have no effect on wm4 may affect bw+ regulation, chromosome pairing, or heterochromatic aggregation, all of which are required for silencing in trans.

Table 2. Specificity of modifiers for heterochromatic rearrangements.

| gene | silencinga | |

| bwD/bw+ | wm4 | |

| pur-alpha | 1 | E |

| vig2 | 1 | E |

| CG10630 | 1 | E |

| CG8036 | 1 | E |

| Jim | 1 | E |

| Ubp64E | 1 | E |

| Samuel | 1 | E |

| psq | 1 | E |

| LA2.1 | 3 | E |

| HR39 | 3 | N |

| l(3)neo38 | 3 | S |

| CG7757 | 3 | E |

| LAS110 | 3 | N |

| MTA70 | 3 | N |

| crol | 4 | N |

| bantam | 4 | N |

| CG3162 | 4 | N |

| CG5794 | 5 | N |

| pita | 6 | N |

| LAS154 | 6 | N |

– Severity of bwD silencing in indicated by ranks (1, severe to 6, de-repressed); severity of wm4 silencing as S (suppressed), E (enhanced) or N (no effect).

Over-expression modifiers do not affect RNAi

Functional RNAi systems are required for heterochromatic silencing in eukaryotes. Nuclear complexes containing small RNAs are thought to target histone modifications to homologous repetitive sequences, and to promote the retention and subsequent degradation of nascent transcripts from those repeats [36]. In Drosophila, the RNA endonuclease Dcr2 is required for both production of post-transcriptional silencing small RNAs and for small RNAs derived from transposable elements in the genome [37]. Genetic evidence in Drosophila indicates a link between RNAi and heterochromatic silencing as well [38]–[40], although the mechanism of how RNAi is converted into chromatin structure has not been detailed. We recovered 10 lines that are implicated in RNA metabolism in our screen (Table 1), and we tested whether over-expression lines might affect bwD silencing by inhibiting RNAi. We used a hairpin construct that eliminates w+ message (GMR-wIR) to assay the effectiveness of RNAi [41]. GMR-wIR eliminates almost all pigmentation in the eye, and this effect requires Dcr2 activity. As the hairpin construct and the over-expressed modifiers are both induced from GMR promoters, the double-strand RNA for knockdown and the modifier are expressed at the same time starting late in the development of the eye.

There were no significant effects of over-expression lines on the extent of w+ knockdown by GMR-wIR, although 3 lines showed a slight increase in eye pigmentation, and 4 lines had a slight decrease (Table 1, Figure S1). In these 7 lines the mis-expression P elements carry a w+ marker, and the marginal effects on knockdown may be due to different levels of w+ expression. Regardless, the severe effect of these insertions on heterochromatic silencing with little effect on knockdown implies that these factors do not affect silencing by altering RNAi.

Most factors require high-level expression to affect silencing

The GMRGAL driver we used in our screen produces high levels of GAL4 late in eye development, immediately before the last S phase and cell division of pigment cells in the 3rd instar imaginal disc [42]. Previous experiments have indicated that heterochromatic silencing varies during the development of the eye [43]. We used the modular nature of the GAL4-UAS system to test if continual production of factors in the eye would also alter silencing. The eyGAL driver produces moderate levels of GAL4 in the eye primordium starting in embryogenesis, and shuts off just before the last cell division in the developing eye [44]. We anticipated that factors may only be effective when expressed with GMRGAL if they are required at high levels to modify silencing. Indeed, we found that the majority (29/34) of lines have no effect on silencing when induced by eyGAL (Table 1).

Only five factors affected bwD silencing when induced by eyGAL4 (Table 1). Induction of the chromatin remodelers xnp and Ino80 have quantitatively similar effects on silencing whether they are induced by GMRGAL or by eyGAL. This implies that moderate expression of these factors is sufficient for their effect. GMRGAL induction of ACF1 has a dramatic de-repression of silencing, but de-repression is more moderate with eyGAL, suggesting that amounts of ACF1 are limiting for de-repression. Late induction of vig2 enhances silencing, but early induction de-represses silencing. Vig2 is normally produced early in development and may promote the formation of heterochromatin, while the related Vig protein may take over its functions in later development [25]. Perhaps early over-expression of Vig2 interferes with function in early development, while later expression interferes with Vig function. Finally, crol is an exceptional case, because over-expression with eyGAL gives more dramatic de-repression than induction by GMRGAL. This line is examined in more detail below.

The effects of early over-expression on silencing could not be determined for 5 lines that are lethal or severely distort the eye in combination with eyGAL (Table 1). These appear to be cases where continuous expression is toxic to cells. It is notable that toxic effects are infrequent in this collection of modifiers. Indeed, when we ubiquitously induced modifier lines with the A5CGAL driver, 19 had no effect on viability (Table 1). This includes seven lines with strong de-repressive effects on silencing when induced by GMRGAL. This is consistent with the observation that some modifiers of heterochromatin silencing are largely dispensable for viability in Drosophila [45]. Lines that are lethal when constitutively expressed are likely to have more general effects on chromatin regulation.

Over-expression of crol leads to heritable de-repression

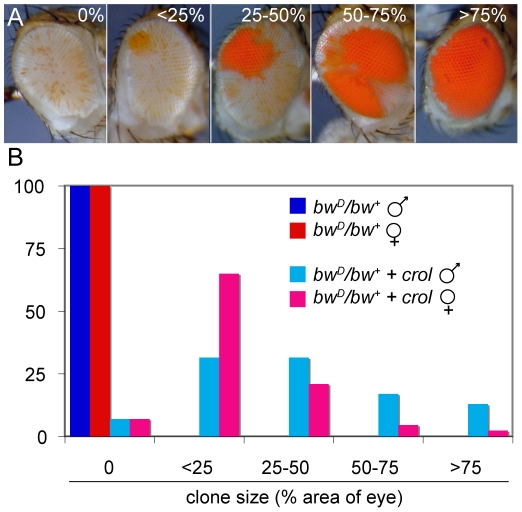

The crol transcription factor is one of the few factors tested that de-represses silencing when continually expressed in the eye (Table 1). Strikingly, continual expression of crol changes the pattern of silencing in bwD/bw+ animals (Figure 2A). The bwD allele normally causes speckled variegation of bw+ that is thought to result from the disruption and re-establishment of inter-chromosome interactions every cell cycle as the eye grows [15], [16]. However, bwD/bw+ animals with continual expression of crol frequently have de-repressed sectors in the eye. Most animals with crol expression show one or more sectors, implying that de-repression is frequent in this genotype (Figure 2B). Sectors appear in a speckled background, implying that bwD silencing remains severe for some cells.

Figure 2. Early over-expression of crol leads to sectored de-repression of bw+.

(A) Early induction of the transcription factor crol with the eyGAL4 driver leads to sectors of complete de-repression in a bwD/bw+ background. Eyes were assigned to 5 ranks based on the percentage of the area of the eye included in de-repressed sectors. (B) The percentage of eyes with de-repressed sectors in males and females with bwD and over-expressing crol is shown (p<10−57 between control and crol-expressing males; p<10−9 between crol-expressing males and females). At least 100 animals were scored for each genotype.

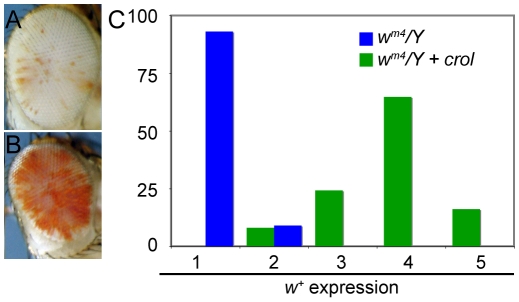

We verified that de-repressed sectors were due to crol expression using an independent over-expression insertion line (d03228, Exelexis Stock Center). Furthermore, increased crol expression with two eyGAL4 drivers also increases the frequency of de-repressed sectors. Continual expression of crol also de-represses wm4 (Figure 3), indicating that this factor can generally modify heterochromatic silencing. Late induction of crol moderately de-represses silencing with bwD and has little or no effect with wm4, implying that the timing of crol expression during development is important for de-repression.

Figure 3. Early over-expression of crol is a general de-repressor of heterochromatic silencing.

(A) The w+ gene in wm4/Y; eyGAL/+ males show severe silencing. (B) In wm4/Y; eyGAL/crolJJ2A males the w+ gene is de-repressed. (C) Eyes from male flies were assigned ranks based on the pigmented area (1, no pigment to 5, mostly pigmented), and the percentage of eyes with w+ expression with and without crol over-expression is shown (p<10−14). At least 40 animals were scored for each genotype.

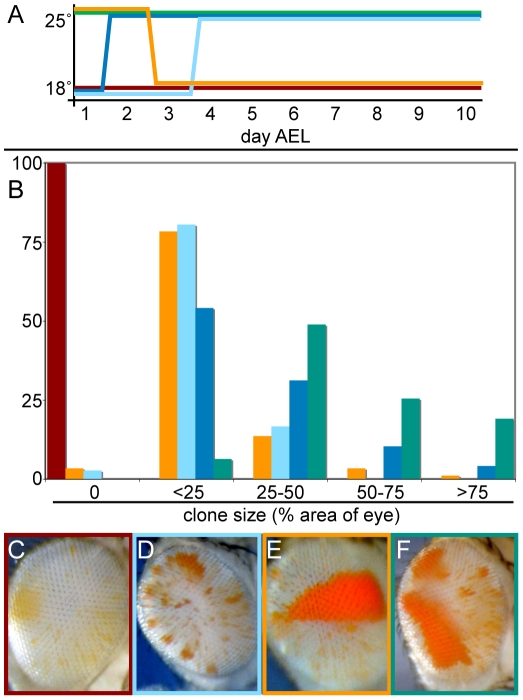

The sectored pattern of variegation suggested that continual crol expression causes somatically heritable de-repression. To test this idea, we reduced the strength of crol over-expression by raising animals at 18°C, where GAL4 is less effective as an activator [46]. Indeed, raising animals at 18° completely blocks the appearance of de-repressed sectors (Figure 4A–4C). This allows us to use temperature shift experiments to determine the developmental timing when crol causes de-repression. We found that animals raised at 18° for early development and then shifted to 25° showed reduced de-repression (Figure 4A and 4B). Strikingly, some animals raised in this regimen showed numerous small sectors (Figure 4D), consistent with the idea that de-repression does not occur early in this regime but often occurs in later development. This idea is supported by our observation that animals shifted to 25° after 1–2 days at 18° show more de-repression than animals shifted to 25° after 3–4 days (Figure 4B). We conclude that crol-stimulated de-repression can occur sporadically throughout development.

Figure 4. Transient crol expression establishes heritable de-repression.

(A) Scheme for temperature shifts from 18°C to 25°C and vice versa. Each colored line represents a temperature regimen after egg collections from eyGAL bwD; st x crolJJ2A; st crosses, and the proportion of clonal de-repression was counted in male progeny. Flies were also raised continuously at 25° (green line) and 18° (red line) as controls. (B) The percentage of eyes with de-repressed sectors for each temperature regimen in (A) is shown. 40–100 animals were scored for each regime. (C–F) Distinctive eyes of animals raised in the temperature regimes indicated by color lines in (A). (C) Development at 18° inhibits de-repression by crol over-expression. (D) Some animals raised at 25° for 2–3 days and then shifted to 18° show single early sectors. (E) Animals raised at 18° for 2–3 days and then shifted to 25° show numerous small sectors. (F) Animals raised at 25° show multiple large de-repressed sectors.

To determine if crol over-expression is required for the establishment of de-repression, for its stable inheritance, or for both, we transiently expressed crol early in development. We raised animals at 25° for embryonic and early larval stages, and then shifted them to 18°. De-repression persisted in this temperature regimen and often appeared as a single sector in the eye (Figure 4E), demonstrating that de-repression can be maintained in the absence of crol expression. Thus, the strong effect of continual crol expression appears to result from multiple de-repression events throughout development (Figure 4F). We conclude that crol is required for de-repression, but de-repression can be maintained through cell divisions without over-expression of the factor.

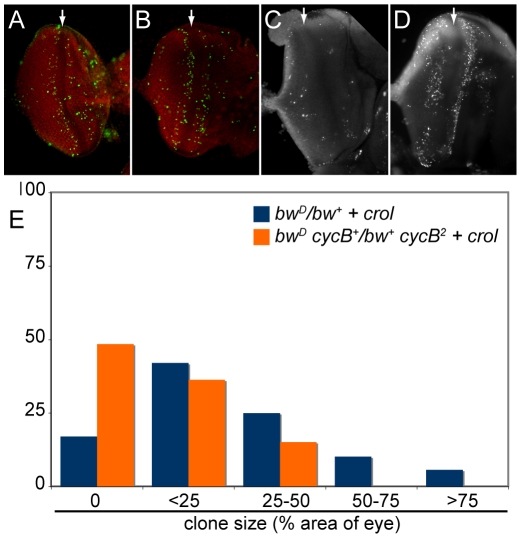

Accelerated cell cycles de-repress silencing

How does crol de-repress silencing? We noted that GMRGAL-induced crol expression resulted in a slight roughening of the eye, suggesting that there may be proliferation defects. Indeed, over-expression of crol promotes cell division in developing wing discs [47]. We confirmed that crol over-expression also promotes cell cycle progression in eye discs. In late third instar larvae, the eye disc contains both mitotically active cells and differentiating cells, and the last two waves of cell divisions in the eye occur on either side of the morphogenetic furrow (MF; [48]). Over-expression of crol causes a substantial increase in the number of mitotic cells on both sides of the MF (Figure 5A and 5B). This is accompanied by increased cell death in these zones (Figure 5C and 5D). Previous studies have shown that increased cell proliferation induces compensatory cell death in developing imaginal discs [49]. Thus, crol induces both accelerated cell cycles and stable de-repression of silencing in the developing eye.

Figure 5. Accelerated cell cycles accompany crol -mediated de-repression.

(A) Mitotic cells (H3-phospho-S10 staining, green) are detected on both sides of the morphogenetic furrow (MF, arrow) in wildtype eye imaginal discs. (B) Over-expression of crol by the eyGAL driver increases the number of mitotic cells in eye imaginal discs. 10 discs for each genotype were examined (p<0.04). (C) Wildtype discs show a small number of apoptotic cells (acridine orange staining). (D) Over-expression of crol stimulates cell death in the mitotically active regions on either side of the MF. 10 discs for each genotype were examined (p<0.004). (E) The percentage of eyes with de-repressed sectors in males over-expressing crol with or without a heterozygous cycB2 mutation is shown. The cycB2 allele significantly reduces sectored de-repression (p<10−5). 60–90 animals were scored for each genotype.

Acceleration of the cell cycle by crol over-expression is suppressed by mutations the mitotic regulator cyclin B (cycB; [47]). We used this to test if cell cycle acceleration by crol causes de-repression. We found that cycB2 dominantly reduces de-repression by crol over-expression (Figure 5E). We conclude that de-repressed clones result from an acceleration of the cell cycle. Notably, cycB mutations have no dominant effect on bwD silencing, demonstrating that silencing and clonal de-repression are genetically distinct processes.

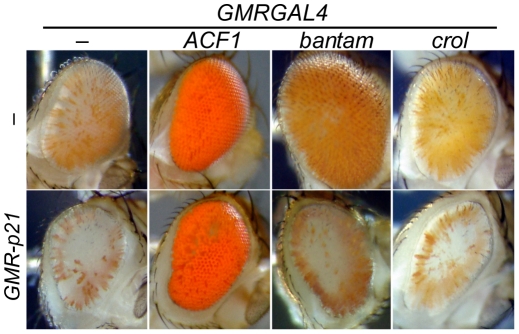

De-repression by crol and bantam is limited to cycling cells

If accelerated cell cycles induced by crol over-expression cause de-repression, then crol over-expression in post-mitotic cells should have no effect on silencing. The GMRGAL driver induces transgenes immediately before the last cell division in the eye, and induction of crol with this driver moderately de-represses bwD silencing. We used the cyclin inhibitor p21 to eliminate the last division in the eye disc [50]; in this background GMRGAL induces crol after the last cell division. We found that eliminating the last cell cycle blocks the de-repressive effect of crol, confirming that crol over-expression is only effective in cycling cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Cell cycle requirements for inducible de-repression.

The GMR-p21 construct blocks Cyclin E activity and eliminates the last cell division in the eye. Flies with GMR-p21 have slightly reduced and roughened eyes, but still show efficient silencing by bwD. GMRGAL4-induced expression of ACF1 strongly de-represses silencing, and this is not affected by GMR-p21. In contrast, de-repression of silencing by crol or bantam over-expression is abrogated by a contemporaneous expression of p21. At least 5 animals were scored for each genotype.

A second factor we identified also implicated cell cycle progression in de-repression. The bantam microRNA promotes cell growth, and indeed, late over-expression of this factor with GMRGAL leads to both de-repression of silencing and expansion of the eye (Figure 6). To determine whether the de-repressive effects of bantam are also limited to cycling cells, we tested if de-repression could occur when p21 was also expressed. We found that eliminating the last cell cycle greatly reduces de-repression caused by bantam over-expression (Figure 6).

Finally, we tested if other over-expression modifiers are also only effective in mitotically active cells. We focused on the 9 lines that show dramatic de-repression (Rank 6 in Table 1). All 9 of these factors show dramatic de-repression when expressed either before or after the last division in the eye (Figure 6). We conclude that the silenced chromatin state is plastic, and over-expression can overcome silencing even in differentiated cells. The bantam and crol factors are exceptional, in that they are only effective in cycling cells.

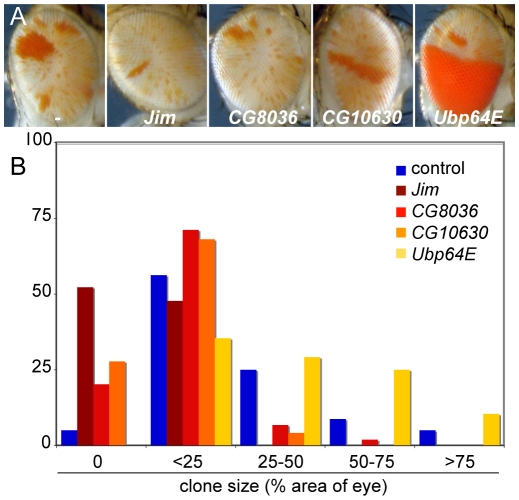

Establishment is distinct from silencing

Over-expression of crol generates bw+ clones, implying that some cells establish de-repressed early in development and their daughter cells maintain de-repression. We used inducible modifiers we recovered to test if enhancers could inhibit establishment or the maintenance of crol-mediated de-repression. Jim, CG8036, CG10630, and Ubp64E are enhancers of silencing when induced late in development, but have no effect when expressed early (Table 1). To test if these factors affect clonal de-repression, we induced each of these factors and crol early in development. While crol induction results in extensive clonal de-repression, contemporaneous expression of Jim, CG8036, or CG10630 strongly reduced clones (Figure 7A and 7B), suggesting that establishment of de-repression is more sensitive than bw+ expression later in development. In contrast, contemporaneous expression of crol and Ubp64E dramatically increases clonal de-repression in the eye (Figure 7B), implying that more cells sporadically switch to a de-repressed state. Thus, while the establishment of de-repression is sensitive to some modifiers of heterochromatic silencing, these appear to be genetically distinct.

Figure 7. Inducible enhancers alter crol-mediated establishment of de-repression.

(A) Representative eyes showing heterochromatic silencing with the early expression of crol contemporaneous with the indicated inducible enhancer. The size and frequency of de-repressed clones is altered by each enhancer, but the background speckled variegation is unchanged. (B) Histograms of the area of the eye included in de-repressed sectors (p<10−3 for all 4 enhancers, at least 45 animals were scored for each genotype).

Discussion

We used an efficient over-expression screen to recover dominant modifiers of heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing. The inducible GAL4-UAS system allows us to limit over-expression from insertion elements to the eye, thereby avoiding potential toxic effects, as well as testing factors that may not be normally expressed in this tissue. Our screen identified a diverse set of 36 factors that are effective for enhancing or de-repressing silencing, including 7 factors have been previously implicated in heterochromatic function. Some of these factors are likely to directly affect heterochromatin structure, while other factors may have more indirect effects. However, the inducible feature of these modifiers allows us to manipulate heterochromatic silencing by controlling the timing and level of modifier expression. Our results show that both the active and the silenced chromatin states are plastic and epigenetic, as they can be reversed even in post-mitotic differentiating cells. Furthermore, inducible control of modifiers allows us to distinguish between establishment and maintenance of silencing during development.

Patterns of variegation are characteristic of individual chromosomal rearrangements that cause silencing. Silencing due to the bwD insertion shows a fine-grained speckled pattern of variegation, and the lack of clonal variegation implies that this rearrangement cannot propagate silenced chromatin state. Long-range interactions between heterochromatic regions within the nucleus are required to silence bw+, and heterochromatic aggregation is thought to be disrupted every cell division. Thus, every daughter cell must re-establish silencing anew after cell division, and even though silencing by bwD is highly efficient, disruption of heterochromatic interactions every mitosis limits the somatic heritability of silencing. Sporadic speckling where ∼5% of pigment cells have bw+ expression is therefore a result of rare and independent de-repression that occur late in eye development.

In spite of this instability, over-expression of the crol transcription factor efficiently de-represses silenced genes, and daughter cells then maintain de-repression. Clonal gene activity in an otherwise silenced population of cells requires that the de-repressed chromatin state be heritable through multiple rounds of mitotic divisions. The speckled variegation of bwD/bw+ makes it surprising that expression of a single factor can confer a somatically heritable state to this genotype. It is likely that the crol factor perturbs a normal process carried out by cells, resulting in an inability to silence.

The de novo generation of de-repressed and stable clones in unstable silencing system has implications for the mechanism of heterochromatic silencing. Our experiments show that expression of crol can establish a heritable de-repressed state as early as embryogenesis, but the bw+ gene is not expressed until eye differentiation ∼5 days later [51]. Thus, the heritable state must be established independently of the expression state of bw+ gene. This distinction has been previously demonstrated for a number of gene activation models, where the establishment of an accessible chromatin state precedes gene activation. For example, the beta-globin locus becomes “open” before transcription initiates in erythrocyte cells [52], [53]. Similarly, monoallelically-expressed loci have “open” and “closed” chromatin features many cell divisions before transcription of one allele begins, and the activated allele is always the “open” locus [54]. Open and closed states of chromatin may correspond to histone modifications that recruit chromatin factors. Our experiments suggest that over-expression of crol induces such an open chromatin state at bw+, thereby permitting its expression later in development.

Crol is a zinc-finger protein that binds chromatin [47], and may directly contribute to inducing an open chromatin state. However, its effect on heterochromatic silencing requires acceleration of the cell cycle, and silencing is restored when cell cycle progression is either delayed with cyclin B mutations or blocked with cyclin E inhibitors. Our identification that the proliferation-inducing bantam microRNA also de-represses silencing confirms that cell cycle progression affects bwD silencing. There is extensive evidence that cell cycle progression is generally important for heterochromatic silencing. New nucleosome assembly during the duplication of chromatin in S phase dilutes histone modifications localized in the genome. The dilution of heterochromatic histone modifications during replication leads to transient de-repression of repetitive sequences, and a closed chromatin state must be re-established [55], [56]. In budding yeast, heterochromatic silencing can be partially established during S phase, but mitosis is required to fully establish silencing [57], [58]. Such requirements may also apply to Drosophila, because elongation of the cell cycle by mutation [59] or by low temperatures [60] enhances silencing. Conversely, our observation that acceleration of the cell cycle de-represses silencing suggests that re-establishment is a slow process.

Cell cycle length may be important for heterochromatic function if silencing requires that heterochromatic closed chromatin states be duplicated every cell cycle. As chromatin duplicates in S phase, and associations between homologs are disrupted in mitosis, heterochromatin at the bw+ locus must be re-established in this interval. Euchromatin and heterochromatin replicate in early and late S phase, respectively, and this temporal separation is important for maintaining the hypo-acetylation of heterochromatin [61]. The bw+ locus may be silenced if pairing with bwD forces it to replicate late and become hypo-acetylated. Alternatively, pairing with bwD may be necessary to add repressive histone modifications after DNA replication. Accelerated cell cycles may drive early replication of bw+ or mitosis before heterochromatic marks are duplicated, leading to the loss of a closed chromatin state. Importantly, our results imply that re-establishment of a closed chromatin state must occur every cell cycle, and if re-establishment fails it cannot be restored.

Regardless of how accelerated cell cycles lead to de-repression, the appearance of de-repressed clones in an otherwise silenced population of cells indicates that once an open chromatin state is established, it is stably propagated through multiple cell cycles. Perhaps open chromatin states are inherently heritable, but simply never occur early in development in bwD/bw+ animals. Indeed, developmental differences in silencing have been previously observed, where dividing cells show severe silencing that “relaxes” upon differentiation [43]. Alternatively, cells may normally switch between open and closed chromatin states throughout development, but rapid cell cycles might prevent establishment of a closed state from an open state. If acceleration of the cell cycle causes early replication and hyper-acetylation of the bw+ locus, this could hinder heterochromatin formation. For example, methylation of histone H3 at lysine-9 is required for heterochromatic silencing, but is blocked by acetylation at this residue [62]. This antagonistic relationship between modifications at this residue may also imply that a third, unmarked chromatin state may affect the stability of silencing. In any case, as the loss of euchromatic modifications can take multiple cell divisions [63], open chromatin states may only slowly switch to a closed state.

Most models for epigenetic systems assume the silenced state is somatically heritable, and propose that heritability is conferred by self-associating properties of silencing proteins. However, silencing also requires continual re-establishment by nascent transcription of repetitive sequences that direct RNAi-dependent histone modifications after every round of chromatin duplication [56]. Our work makes it clear that active states can also be somatically heritable, and suggests that somatically heritable patterns need not imply special features of chromatin-associated proteins. Stable de-repression has also been observed with Polycomb-dependent regulatory elements [64], suggesting that heritability is a common property of chromatin-based silencing systems. Thus, inheritance of either open or of closed chromatin states may generate clonal patterns of gene expression during development.

Materials and Methods

All crosses were grown at 25°C or 18°C on standard cornmeal medium. Stocks, mutations, and balancer chromosomes not described here are detailed in Flybase (www.flybase.org).

GAL4 driver lines

The lines referred to as ‘GMRGAL’ and ‘A5CGAL’ are previously described white-deficient versions of drivers for late eye-specific and constitutive expression of GAL4, respectively [65]. For constitutive eye-specific expression, we used the P[eyGAL, w+]3-8 line, referred to as eyGAL [66]. For experiments with In(1)wm4, the eyGAL driver was destabilized using TMS, P[Delta2–3] to generate a white-deficient insertion that retained eye-specific expression of GAL4.

Mis-expression insertion screens

We used st or v36f to eliminate all ommochrome pigments from the eye. In these backgrounds, bw+ cells appear red, while cells with bw+ silencing appear white. A preliminary screen was performed using a w+-marked P[EP]2339 (inserted at 59E) as a donor for mutagenesis. We crossed P[EP]2339/CyO; st virgins to Dr/TMS, P[Delta2–3] males, and then crossed individual Cy+ Sb male progeny to GMRGAL bwD/CyO; st females. Cy+ Sb+ progeny with enhanced or de-repressed bw+ silencing were recovered and mated to a w1118 stock for extraction of new P[EP] insertions.

A second screen used the y+-marked P[LA] construct for mutagenesis. We first transposed P[LA]4 [17] onto FM7i using P transposase, and then used the resultant chromosome FM7i, P[LA]4.2 as a donor chromosome. We crossed y/FM7i, P[LA]4.2; st females to Dr/TMS, P[Delta2–3] males, and then crossed individual progeny B Sb males to y; GMR bwD/CyO; st females. Cy+ Sb+ y+ males with enhanced or de-repressed bw+ silencing were recovered and mated to a y stock for extraction of new P[LA] insertions.

Candidate gene insertion lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington IN) and the Exelexis Stock Center (Boston MA) and tested for effects on bwD silencing in v36f; GMRGAL bwD/+ males. To assess if effects were dependent on expression of a gene adjacent to the P element, each insertion from screens and candidate tests were re-assessed with GAL4 (GMRGAL bwD/insertion) and without GAL4 (bwD/insertion). Progeny from crosses were scored and photographed 3–4 days after eclosion as previously described [67].

Identification of target sites

New insertion sites were mapped using inverse PCR according to published protocols [68]. Genomic DNA from balanced lines was purified and digested using MspI or RsaI restriction enzymes, ligated, and used for PCR amplification using the following primers: P[LA] 5′ ends, LA(f).1/LA(r).1; P[LA] 3′ ends, Pry4/Pry1, or Sp6/Pry4; P[EP] 5′ ends, Pwht1/Plac1; P[EP] 3′ ends, Pry4/Pry1. Products from all 3′ ends were sequenced using the nested primer Spep1, for P[LA] 5′ends using LA(f)seq1, and for P[EP] 5′ ends using Plac1. The gene responsible for effects on heterochromatic gene-silencing was inferred to be the nearest gene down-stream of the inducible promoter.

Constructs used to characterize modifiers

We tested whether P[LA] modifiers of bwD silencing altered wm4 silencing by crossing In(1)wm4h; GMRGAL females to each insertion line and scoring silencing in male progeny. Insertion-bearing progeny were divided into 5 ranks based on the extent of wm4 silencing and compared to silencing in siblings carrying a dominant marker (CyO or Sco for chromosome 2 inserts, and Sb for chromosome 3 inserts). At least 40 flies were scored for each genotype, and assessed for statistical significance using Mann-Whitney U tests. To test if insertions affected RNAi-mediated gene-silencing, we crossed each insertion line to GMRGAL; P[GMR-wIR] [69] and scored w+ expression. To determine if modifying effects of insertions required expression in dividing cells, we used the cyclin inhibitor p21 to block cell cycle progression in the GMR expression domain of the eye [50]. We crossed each insertion line to v36f; GMRGAL bwD; P[GMR-p21,w+] and scored silencing in male progeny.

Eye disc cytology

Imaginal eye-antennal discs were dissected from late 3rd instar larvae in PBS. For detection of apoptosis, discs were incubated in 5 µg/mL acridine orange/PBS for 5 minutes, and then imaged using FITC excitation and emission filters. For detection of mitotic cells, discs were fixed with 2% formaldehyde, and stained with antisera to the mitosis marker H3-S10-phosphorylation (Millipore).

Supporting Information

Over-expression modifiers do not affect RNAi. GMRGAL induces over-expression from a mis-expression insertion and the mini-w+ marker in the transgene, and GMR-wIR produces hairpin RNAs that knock-down the w+ transcript through RNAi. Over-expression of Orc6 does not alter heterochromatic silencing and was used as a control, where RNAi of w+ is efficient. Knock-down of mini-w+ with over-expression of Rm62 appears more efficient, while knock-down with over-expression of P[EP]Su25 is decreased. Other tested modifiers had no effect on RNAi knock-down.

(10.01 MB EPS)

Genomic positions of modifier insertions.

(0.02 MB XLS)

Candidate genes with no effect on silencing.

(0.02 MB XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Carthew for the GMR-wIR stock, Ishwar Hariharan for the GMR-p21 stock, Jonathan Diah, Devorah Freudiger, and Josephine Lee for technical help, and Welcome Bender for suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM068696 to KA. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:273–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolffe AP. New York: Academic Press; 1998. Chromatin: Structure and Function. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuter G, Wolff I. Isolation of dominant suppressor mutations for position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:516–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00293947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuter G, Werner W, Hoffmann HJ. Mutants affecting position-effect heterochromatinization in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma. 1982;85:539–551. doi: 10.1007/BF00327349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebert A, Lein S, Schotta G, Reuter G. Histone modification and the control of heterochromatic gene silencing in Drosophila. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:377–392. doi: 10.1007/s10577-006-1066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallrath LL, Elgin SC. Position effect variegation in Drosophila is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1263–1277. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seum C, Delattre M, Spierer A, Spierer P. Ectopic HP1 promotes chromosome loops and variegated silencing in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2001;20:812–818. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Danzer JR, Alvarez P, Belmont AS, Wallrath LL. Effects of tethering HP1 to euchromatic regions of the Drosophila genome. Development. 2003;130:1817–1824. doi: 10.1242/dev.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rorth P. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12418–12422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talbert PB, LeCiel CD, Henikoff S. Modification of the Drosophila heterochromatic mutation brownDominant by linkage alterations. Genetics. 1994;136:559–571. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henikoff S, Dreesen TD. Trans-inactivation of the Drosophila brown gene: evidence for transcriptional repression and somatic pairing dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6704–6708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Spreading of silent chromatin: inaction at a distance. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:793–803. doi: 10.1038/nrg1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dernburg AF, Broman KW, Fung JC, Marshall WF, Philips J, et al. Perturbation of nuclear architecture by long-distance chromosome interactions. Cell. 1996;85:745–759. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Csink AK, Henikoff S. Large-scale chromosomal movements during interphase progression in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:13–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harmon B, Sedat J. Cell-by-cell dissection of gene expression and chromosomal interactions reveals consequences of nuclear reorganization. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minye H, Merriam J. Induction of P element transposition using 2–3 transposase to determine whether the number of inserts affects transposition rate in Drosophila melanogaster. D I S. 2001;84:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwendemann A, Lehmann M. Pipsqueak and GAGA factor act in concert as partners at homeotic and many other loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12883–12888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202341499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henchoz S, De Rubertis F, Pauli D, Spierer P. The dose of a putative ubiquitin-specific protease affects position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5717–5725. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moshkin YM, Armstrong JA, Maeda RK, Tamkun JW, Verrijzer P, et al. Histone chaperone ASF1 cooperates with the Brahma chromatin-remodelling machinery. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2621–2626. doi: 10.1101/gad.231202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fyodorov DV, Blower MD, Karpen GH, Kadonaga JT. Acf1 confers unique activities to ACF/CHRAC and promotes the formation rather than disruption of chromatin in vivo. Genes Dev. 2004;18:170–183. doi: 10.1101/gad.1139604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneiderman JI, Sakai A, Goldstein S, Ahmad K. The XNP remodeler targets dynamic chromatin in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14472–14477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905816106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassett AR, Cooper SE, Ragab A, Travers AA. The chromatin remodelling factor dATRX is involved in heterochromatin formation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Csink AK, Linsk R, Birchler JA. The Lighten up (Lip) gene of Drosophila melanogaster, a modifier of retroelement expression, position effect variegation and white locus insertion alleles. Genetics. 1994;138:153–163. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gracheva E, Dus M, Elgin SC. Drosophila RISC component VIG and its homolog Vig2 impact heterochromatin formation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragab A, Thompson EC, Travers AA. High mobility group proteins HMGD and HMGZ interact genetically with the Brahma chromatin remodeling complex in Drosophila. Genetics. 2006;172:1069–1078. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.049957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirano T. At the heart of the chromosome: SMC proteins in action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:311–322. doi: 10.1038/nrm1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin CH, Li B, Swanson S, Zhang Y, Florens L, et al. Heterochromatin protein 1a stimulates histone H3 lysine 36 demethylation by the Drosophila KDM4A demethylase. Mol Cell. 2008;32:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lloret-Llinares M, Carre C, Vaquero A, de Olano N, Azorin F. Characterization of Drosophila melanogaster JmjC+N histone demethylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2852–2863. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillon N, Festenstein R. Unravelling heterochromatin: competition between positive and negative factors regulates accessibility. Trends Genet. 2002;18:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02648-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu BY, Bishop CP, Eissenberg JC. Developmental timing and tissue specificity of heterochromatin-mediated silencing. EMBO J. 1996;15:1323–1332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wines DR, Talbert PB, Clark DV, Henikoff S. Introduction of a DNA methyltransferase into Drosophila to probe chromatin structure in vivo. Chromosoma. 1996;104:332–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00337221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sass GL, Henikoff S. Comparative analysis of position-effect variegation mutations in drosophila melanogaster delineates the targets of modifiers. Genetics. 1998;148:733–741. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motamedi MR, Hong EJ, Li X, Gerber S, Denison C, et al. HP1 proteins form distinct complexes and mediate heterochromatic gene silencing by nonoverlapping mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2008;32:778–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghildiyal M, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Li C, Du T, et al. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science. 2008;320:1077–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pal-Bhadra M, Leibovitch BA, Gandhi SG, Rao M, Bhadra U, et al. Heterochromatic silencing and HP1 localization in Drosophila are dependent on the RNAi machinery. Science. 2004;303:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1092653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin H, Lin H. An epigenetic activation role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2007;450:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature06263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fagegaltier D, Bouge AL, Berry B, Poisot E, Sismeiro O, et al. The endogenous siRNA pathway is involved in heterochromatin formation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21258–21263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809208105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, et al. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell. 2004;117:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu BY, Eissenberg JC. Time out: developmental regulation of heterochromatic silencing in Drosophila. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:50–59. doi: 10.1007/s000180050124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quiring R, Walldorf U, Kloter U, Gehring WJ. Homology of the eyeless gene of Drosophila to the Small eye gene in mice and Aniridia in humans. Science. 1994;265:785–789. doi: 10.1126/science.7914031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tschiersch B, Hofmann A, Krauss V, Dorn R, Korge G, et al. The protein encoded by the Drosophila position-effect variegation suppressor gene Su(var)3-9 combines domains of antagonistic regulators of homeotic gene complexes. EMBO J. 1994;13:3822–3831. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busson D, Pret AM. GAL4/UAS targeted gene expression for studying Drosophila Hedgehog signaling. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;397:161–201. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-516-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell N, Cranna N, Richardson H, Quinn L. The Ecdysone-inducible zinc-finger transcription factor Crol regulates Wg transcription and cell cycle progression in Drosophila. Development. 2008;135:2707–2716. doi: 10.1242/dev.021766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolff T, Ready DF. The beginning of pattern formation in the Drosophila compound eye: the morphogenetic furrow and the second mitotic wave. Development. 1991;113:841–850. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reis T, Edgar BA. Negative regulation of dE2F1 by cyclin-dependent kinases controls cell cycle timing. Cell. 2004;117:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Nooij JC, Hariharan IK. Uncoupling cell fate determination from patterned cell division in the Drosophila eye. Science. 1995;270:983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomancak P, Beaton A, Weiszmann R, Kwan E, Shu S, et al. Systematic determination of patterns of gene expression during drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groudine M, Weintraub H. Activation of globin genes during chicken development. Cell. 1981;24:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schubeler D, Francastel C, Cimbora DM, Reik A, Martin DI, et al. Nuclear localization and histone acetylation: a pathway for chromatin opening and transcriptional activation of the human beta-globin locus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:940–950. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mostoslavsky R, Singh N, Tenzen T, Goldmit M, Gabay C, et al. Asynchronous replication and allelic exclusion in the immune system. Nature. 2001;414:221–225. doi: 10.1038/35102606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen ES, Zhang K, Nicolas E, Cam HP, Zofall M, et al. Cell cycle control of centromeric repeat transcription and heterochromatin assembly. Nature. 2008;451:734–737. doi: 10.1038/nature06561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kloc A, Zaratiegui M, Nora E, Martienssen R. RNA interference guides histone modification during the S phase of chromosomal replication. Curr Biol. 2008;18:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aparicio OM, Gottschling DE. Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1133–1146. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lau A, Blitzblau H, Bell SP. Cell-cycle control of the establishment of mating-type silencing in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2935–2945. doi: 10.1101/gad.764102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Csink AK, Henikoff S. Genetic modification of heterochromatic association and nuclear organization in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;381:529–531. doi: 10.1038/381529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spofford J. Ashburner M, Novitski E, editors. Position-effect varigation in Drosophila. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. 1976. 955

- 61.Zhang J, Xu F, Hashimshony T, Keshet I, Cedar H. Establishment of transcriptional competence in early and late S phase. Nature. 2002;420:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O'Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, et al. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature. 2000;406:593–599. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katan-Khaykovich Y, Struhl K. Heterochromatin formation involves changes in histone modifications over multiple cell generations. EMBO J. 2005;24:2138–2149. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cavalli G, Paro R. The Drosophila fab-7 chromosomal element conveys epigenetic inheritance during mitosis and meiosis. Cell. 1998;93:505–518. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. Modulation of a transcription factor counteracts heterochromatic gene silencing in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;104:839–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hazelett DJ, Bourouis M, Walldorf U, Treisman JE. Decapentaplegic and wingless are regulated by Eyes Absent and Eyegone and interact to direct the pattern of retinal differentiation in the eye disc. Development. 1998;125:3741–3751. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahmad K, Golic KG. Somatic reversion of chromosomal position effects in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;144:657–670. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang AM, Rehm EJ, Rubin GM. Recovery of DNA sequences flanking P-element insertions in Drosophila: inverse PCR and plasmid rescue. CSH Protoc. 2009;2009:5199. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee YS, Carthew RW. Making a better RNAi vector for Drosophila: use of intron spacers. Methods. 2003;30:322–329. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Over-expression modifiers do not affect RNAi. GMRGAL induces over-expression from a mis-expression insertion and the mini-w+ marker in the transgene, and GMR-wIR produces hairpin RNAs that knock-down the w+ transcript through RNAi. Over-expression of Orc6 does not alter heterochromatic silencing and was used as a control, where RNAi of w+ is efficient. Knock-down of mini-w+ with over-expression of Rm62 appears more efficient, while knock-down with over-expression of P[EP]Su25 is decreased. Other tested modifiers had no effect on RNAi knock-down.

(10.01 MB EPS)

Genomic positions of modifier insertions.

(0.02 MB XLS)

Candidate genes with no effect on silencing.

(0.02 MB XLS)