Abstract

An SCD is a pathologic hole (or dehiscence) in the bone separating the superior semicircular canal from the cranial cavity that has been associated with a conductive hearing loss in patients with SCD syndrome. The conductive loss is defined by an audiometrically determined air-bone gap that results from the combination of a decrease in sensitivity to air-conducted sound and an increase in sensitivity to bone-conducted sound. Our goal is to demonstrate, through physiological measurements in an animal model, that mechanically altering the superior semicircular canal (SC) by introducing a hole (dehiscence) is sufficient to cause such an air-bone gap. We surgically introduced holes into the SC of chinchilla ears and evaluated auditory sensitivity (cochlear potential) in response to both air- and bone-conducted stimuli. The introduction of the SC hole led to a low-frequency (< 2000 Hz) decrease in sensitivity to air-conducted stimuli and a low-frequency (< 1000 Hz) increase in sensitivity to bone-conducted stimuli resulting in an air-bone gap. This result was consistent and reversible. The air-bone gaps in the animal results are qualitatively consistent with findings in patients with SCD syndrome.

1. Introduction

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SCD) syndrome is characterized by a hole (a dehiscence) in the bone between the membranous superior canal and the cranial cavity. Patients with SCD syndrome often present with vestibular symptoms including sound and/or static pressure-induced vertigo (Minor et al., 1998; Cremer et al., 2000; Minor, 2000), but some SCD patients present with auditory symptoms including hyper-sensitivity to bone-conducted (BC) sounds, and a decreased sensitivity to air-conducted (AC) sound (Brantberg et al., 2000; Minor et al., 2003; Mikulec et al., 2004; Limb et al. 2006). A typical audiogram for a patient with an SCD-associated hearing loss shows decreased BC thresholds (increased sensitivity) of 5 to 15 dB and increased AC thresholds (decreased sensitivity) of 20 to 40 dB at frequencies less than 1000 Hz (Mikulec et al., 2004). The air-bone gap, calculated as the dB difference between the AC and BC auditory thresholds, is considered diagnostic for the presence of a conductive hearing loss. The majority of cases with air-bone gaps in humans that are greater than 15 dB are attributed to middle-ear pathologies, such as otosclerosis, that effect the middle-ear's ability to conduct sound to the inner ear. In the case of SCD syndrome the opposing changes in AC and BC thresholds can lead to air-bone gaps of 25-55 dB and an apparent conductive hearing loss even though there is no middle-ear pathology (Mikulec et al., 2004; Limb et al. 2006).

In the normal ear there are two primary windows for sound flow into and out of the inner ear: the round window, and the oval window.1 In SCD syndrome the dehiscence acts as a pathological ‘third window’ in the inner ear. This open window is the proposed mechanism for the SCD-induced changes in auditory sensitivity (Minor et al., 1998; Rosowski et al., 2004; Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2007) that result in an air-bone gap and the apparent conductive hearing loss. The SCD introduces a pathological pathway for sound flow between the inner ear and the cranial cavity and in response to AC stimuli this pathway shunts volume velocity away from the cochlea, via the dehiscent canal, resulting in decreased auditory sensitivity and pathological vestibular stimulation of the dehiscent canal (Carey et al., 2000). In response to BC stimuli we propose that the third-window shunt pathway alters the pressure difference across the basilar membrane by altering the acoustic impedance on the vestibular side of the cochlear partition (Békésy, 1960; Rosowski et al., 2004) and leads to changes in auditory sensitivity.

Understanding the mechanisms of sound transmission to the inner ear in response to both AC and BC sound stimuli is important for understanding the air-bone gap. For AC stimuli, sound enters the air-filled external auditory meatus and is coupled to the inner ear via the oval window by motions of the tympanic membrane and ossicles. In clinical bone conduction measurements, vibratory stimuli are delivered to the head, typically at the mastoid bone behind the ear. The mechanisms of the transmission of sound to the cochlea via bone conduction in the normal ear are multiple and the relative contributions of the different paths are not completely defined - as reviewed by Tonndorf (1972), and Stenfelt and Goode (2005). It is hypothesized that there are as many as four basic routes for BC sound transmission to the cochlea including: a) a tympano-ossicular compression route, which is responsible for the occlusion effect, where sound is produced in the ear canal by vibration of the surrounding bone and tissues and is then conducted to the inner ear via the tympano-ossicular system; b) the inertia of the coupled ossicular system and cochlear fluids producing relative motion of the head and cochlear fluids that mimics the relative motions produced by air-conducted sound (Stenfelt and Goode, 2005); c) compressional bone-conduction caused by motions of cochlear fluid evoked by compressional changes in the volume of the bony cochlear boundaries (Békésy, 1960); d) a coupling of the pressures produced in the soft-tissues within the skull to the inner ear through the cochlear and vestibular aqueduct and along the nerves and vessels that enter the cochlea from the brain (Freeman et al., 2000; Sohmer et al., 2000).

While the pressure-coupling hypothesis (d) depends on the presence of additional ‘windows’ into the cochlea in the healthy ear, the other three mechanisms are thought to function in the healthy ear with two well-defined cochlear windows, the oval and round windows. In tympano-ossicular (a) and inertial bone conduction (b) the stimulus induces coupled motions of the tympanic membrane, ossicles and cochlear fluids, much like those produced by air-conducted sound. In compressional bone-conduction (c) inequalities in the impedances of the oval and round windows and the asymmetric placement of the vestibular system relative to the cochlear partition are thought to contribute to the asymmetric volume-velocity flow within the ear that results in a sound-pressure difference across the cochlear partition (Békésy, 1960; Tonndorf, 1972; Rosowski, 2009).

In this paper we evaluate the effect of an SCD on the auditory system, both in response to AC and BC sound stimuli. Previous work has demonstrated an SCD-induced decrease in sensitivity to AC stimuli in chinchilla (Songer and Rosowski, 2005). We expand on that work by pairing measurements of the SCD-induced change in cochlear potential (CP) in response to both AC and BC stimulation to define an air-bone gap in each animal, analogous to the audiometrically determined air-bone gap in patients. We define this experimentally derived air-bone gap as the dB value of the ratio of the dehiscence-induced changes in cochlear potential (CP) in response to BC and AC stimuli. Other work has suggested dehiscence associated increases in BC sensitivity (Songer et al., 2004; Sohmer et al., 2004). The work reported here expands on this previous work in four key aspects: 1) ensuring middle-ear muscle immobilization, 2) demonstrating the reversibility of the effect, 3) evaluating the effect of AC stimulation in the same ear, and 4) evaluating the effect of dehiscence size.

2. Methods

The chinchilla was chosen as the animal model of SCD for this work due to its easily accessible superior canal (SC), its range of hearing, which is similar to that in humans (20 Hz – 20000 Hz), and its use in previous studies of the effect of SCD on auditory and vestibular function (Hirvonen et al., 2001; Songer et al., 2004; Songer and Rosowski, 2005; Songer and Rosowski, 2006). The surgical preparation has been described previously (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) and will be summarized here.

2.1 Surgical Methods

For each experiment, the chinchilla is anesthetized with pentobarbital and ketamine with boosters every two hours or as necessary. The ear canal is exposed, and an acoustic coupler is glued into the canal to allow for the placement of an acoustic source and microphone. The posterior bulla cavity is exposed, a section of the posterior-lateral bullar wall is removed and the round window (RW) is identified; a hole in the roof of the superior bulla is then created and the SC is identified. All holes into the middle ear are closed with moist cotton or ear-mold impression material between procedures to limit drying of the mucosal surfaces; however, these holes are completely open during all measurements. In later experiments the tensor-tympani tendon was cut and the tympanic segment of the facial nerve sectioned via the superior bulla hole. These later manipulations prevented spontaneous contractions of the middle-ear muscles that are sometimes seen in anesthetized chinchillas (Rosowski et al., 2006).

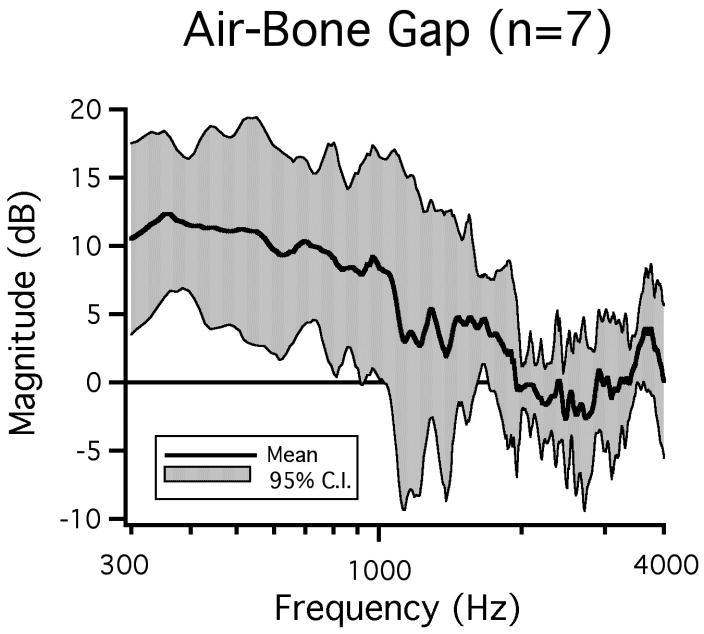

The cochlear potential (CP) is a gross auditory potential measured near the round window that does not separate the cochlear microphonic from the compound action potential. The CP was measured using a silver wire electrode positioned in the RW niche via the posterior bulla cavity. For measurements with bone-conducted stimuli, the top of the skull is prepared by removing the skin and superficial tissues, and the bone conduction stimulator is glued (using cyano-acrylate glue) to the skull. The bone conduction (BC) vibrator has a contact area of approximately 350 mm2. Figure 2 illustrates the relative locations of the SCD, the BC vibrator, the earphone and the CP electrode.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustrating the location of the SCD and superior canal in the middle-ear air space; the placement of earphone in the ear canal; the placement of the CP electrode in the round window niche; and the BC stimulator affixed to the skull.

Two different types of physical stimulus generators are used in this study: an earphone (Knowles ED-1913) for AC stimuli and a clinical bone-conduction vibrator for BC stimuli (Radioear B71). The input signal for both stimulators is a broadband log-chirp with frequency components at 11 Hz intervals from 11 to 24000 Hz. In a log-chirp the magnitude of the different frequency components decreases as the square root of the frequency of the component. This scaling emphasizes the low-frequency stimulus components, as the low frequencies are where the greatest effects of dehiscence have been observed (Songer et al., 2004; Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2006). While the electronic input signals contain energy at frequencies up to 24000 Hz, the low-pass nature of the BC stimulator (Songer et al., 2004) restricts the effective BC stimulus to frequencies below 4000 Hz, and the low-pass characteristics of the earphone restricts the AC stimulus to frequencies below 8000 Hz. We are interested in comparing AC and BC responses so all of the data for this paper will be plotted with reference to the effective stimulus range for our bone conduction vibrator (300 to 4000 Hz). The CP is measured at three different stimulus levels in response to both AC (between 70 and 95 dB SPL) and BC (displacements of the bone adjacent to the superior canal between 0.4 and 1.6 μm) stimuli to check repeatability and ascertain linearity. Additionally, the AC and BC levels were chosen so that the CP recorded in response to the different stimuli was similar in magnitude.

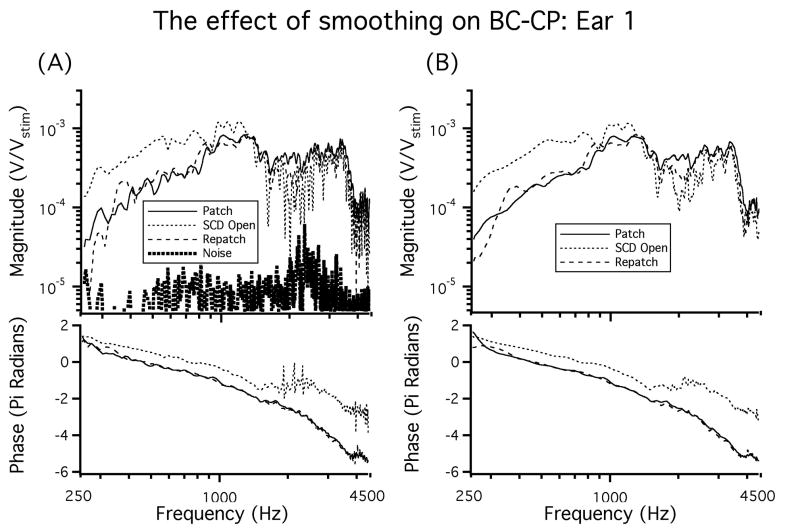

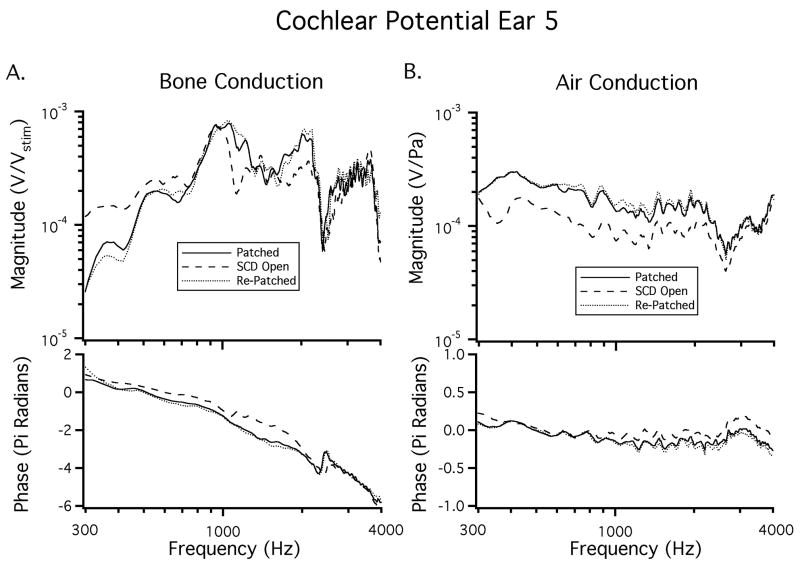

CP was measured in a total of 22 ears. The BC-CP data are normalized by system gains and attenuations and are presented as volts of CP normalized by stimulus voltage (Vstim) with units of V/V. In response to AC sound stimuli the CP is normalized by the sound pressure at the tympanic membrane (PTM) with units of V/Pa. All of the normalized CP data are then smoothed using the loess smoothing algorithm, based on local linear regression (Cleveland, 1993). Figure 3 shows the effect of smoothing in an example ear. Additionally, this figure illustrates rapid phase accumulation in the BC response, which is altered above 1500 Hz by opening the SCD.

Figure 3.

A) The CP recorded from an ear in the patch-unpatch (SCD Open)-repatch states. A low frequency increase in CP is observed between 250 Hz and 500 Hz. A shift in phase is also observed above 1500 Hz in the SCD open condition. B) The CP in response to BC after the data is smoothed using the loess smoothing algorithm.

In Figure 3A the noise floor (measured while presenting a greatly attenuated stimulus) is also illustrated. In some ears the BC-CP measurement in the intact ear at frequencies below 300 Hz is close to the noise floor, due to the pass-band of the bone-conduction stimulator, and CP data for frequencies below 300 Hz are not included in the remainder of the figures.

In each ear measurements were made with the SC intact and after introducing a large SC hole, at least 0.4 mm wide and 1 mm long. The SC holes were introduced by removing a segment of the bone overlying the SC within the superior bullar cavity (Figure 2) using a fine chisel. In some ears a smaller SC hole was made first and then the hole was enlarged to evaluate the effect of dehiscence size on auditory symptoms. Additionally, in nine of the ears, measurements were made after repeatedly patching the SC hole with cyano-acrylic glue (Superglue ®) and removing the patch. In the nine ears in which measurements were made in response to both AC and BC sound stimuli, both the superior and posterior bulla holes were left widely opened. In an additional 13 ears in which measurements were made in response to just BC stimuli, the superior bulla hole was left widely opened, but the posterior cavity was closed.

2.2 Data Analysis

Two data sets are evaluated in this study. In the first set we evaluated CP in response to BC sound stimuli in 13 ears before and after the introduction of a SC hole. In these ears we did not carefully control the state of the middle-ear muscles and we did not evaluate the effect of patching the SC hole with a rigid, water-tight seal. In evaluation of CP in response to AC sound in a subsequent study (Songer and Rosowski, 2005; Rosowski et al., 2006) it was established that the middle-ear muscles could affect sensitivity to AC sound, and a procedure for effectively patching the dehiscence was established. This work led us to collect CP data in an additional nine ears in which the middle-ear muscles were controlled (the tensor tendon and the tympanic branch of the facial nerve sectioned) and the effect of patching the SC hole was evaluated in response to both AC and BC sound stimuli.

2.3 CP in response to BC stimuli alone

In the 13 ears of the first data set (Songer et al. 2004), we evaluated the CP in response to BC sound stimuli. In these ears the CP electrode was glued in place to minimize potential shifts of the electrode that could introduce changes in the measured CP. The CP was then measured in the intact ear. In three of these ears a small SC hole (< 0.4 mm × 0.4 mm in diameter) was introduced using a fine chisel, measurements were made and then the hole was enlarged (to at least 0.4 mm wide and 1 mm long) and an additional set of measurements were made. In the other 10 ears the initial SC hole was large (at least 0.4 mm wide and 1 mm long). In these 13 ears the middle-ear muscles were not severed and the effect of patching the dehiscence was not established.

2.4 CP in response to both AC and BC stimuli

In the nine ears of the second data set, CP was measured in response to both AC and BC stimuli before and after inducing and repeatedly patching and unpatching the SC hole. The sound pressure at a point in the ear canal about 3-4 mm lateral to the tympanic membrane, PTM, was also measured in response to both BC and AC stimuli, where the PTM microphone was integrated into the calibrated sound source sealed in the ear canal during all measurements in these nine ears. With AC stimuli, PTM was used to normalize the CP (Songer and Rosowski, 2005). In response to BC, the exact stimulus to the inner ear is unknown and the voltage to the stimulator Vstim is used to normalize the CP.

Seven of the nine ears in this second set exhibited stability and reversibility in the measurements of both CP and PTM in response to both AC and BC stimuli across long periods of time and through repeated patching and unpatching of the dehiscence. Two of the nine ears, not included in the summary results, failed to demonstrate stability or reversibility across any of the conditions. However, even in the ears in which we observed repeatable affects of patching and unpatching the dehiscence, there was often a small difference between the CP measurements made prior to placing the dehiscence and those measured after patching. That is, some small fraction of the change in CP produced by the initial dehiscence was not reversed by patching the dehiscence. Repeatedly patching, unpatching, and repatching the dehiscence did not lead to subsequent shifts (Figure 3).

The small differences in CP magnitude observed after patching relative to that in the intact ear may reflect a small but real difference between the intact bony wall and the patch, but it may also be due to other complications. While in the first data set we made sure to minimize motions of the head, in this second set it was often necessary to move the animal between measurements recorded in the intact state and the introduction of the SC hole to ensure proper electrode placement. Moving the animal could cause small shifts in CP electrode placement, alterations in how tightly the head is coupled to the head holder, and potential shifts in the earphone coupling. Additionally, the introduction of the SC hole typically results in increased fluid accumulation in the middle ear largely due to the aggravation of the mucosa. Such fluid accumulations, especially if they occur in and around the round window, may alter the measured CP in response to BC stimuli. Additionally, it is possible that the physical act of introducing the hole causes a small hearing loss measured as a drop in CP.

Despite the small differences observed between the intact ear and those observed in the patched ear, a large degree of stability and reversibility was observed between the subsequent patched and repatched states in the seven included ears. We attribute the greater stability after the initial introduction of the dehiscence to the ability to patch, unpatch, and repatch the dehiscence without having to further adjust the position of the animal, earphone, or electrode. Due to the improved preparation stability observed in comparisons of the patched data to the repatched, we present data from the patched-, unpatched- and repatched-states for this data set. To quantify stability, we evaluated the RMS difference (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) between the patched and the re-patched conditions:

| (1) |

where n refers to the number of data points between 300 Hz and 2000 Hz, CPrepatched is the measured CP after the hole is repatched and CPpatched is the CP after the hole is initially patched. We only included data sets that had an RMS Difference less than an arbitrarily threshold of 0.6. Using this criterion seven of the nine ears are included in the evaluation of CP in the remainder of this paper.

In two of the seven repeatable ears we also evaluated the effect of SC hole size. In these ears the baseline CP in the intact ear was first determined, then the SC was exposed and a small hole (diameter 0.2-0.3 mm) was introduced surgically. The SC hole was then enlarged (diameter ≥ 0.4 mm and 1 mm long) and CP measurements were repeated.

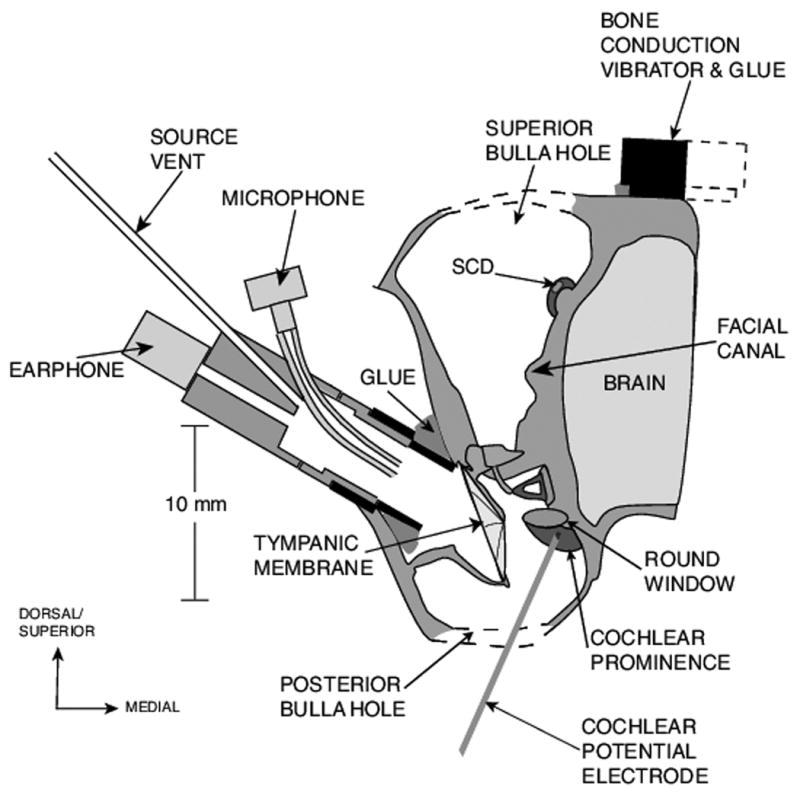

3. Results: SCD and Bone Conduction

Cochlear potential (CP) was measured in response to bone-conducted (BC) stimuli in the intact ear, after the introduction of an SC hole (a dehiscence), and after repeatedly patching and unpatching the SC hole.

3.1 The effect of SCD on CP produced by BC stimulation

3.1.1 The effect of an SC hole on BC-CP

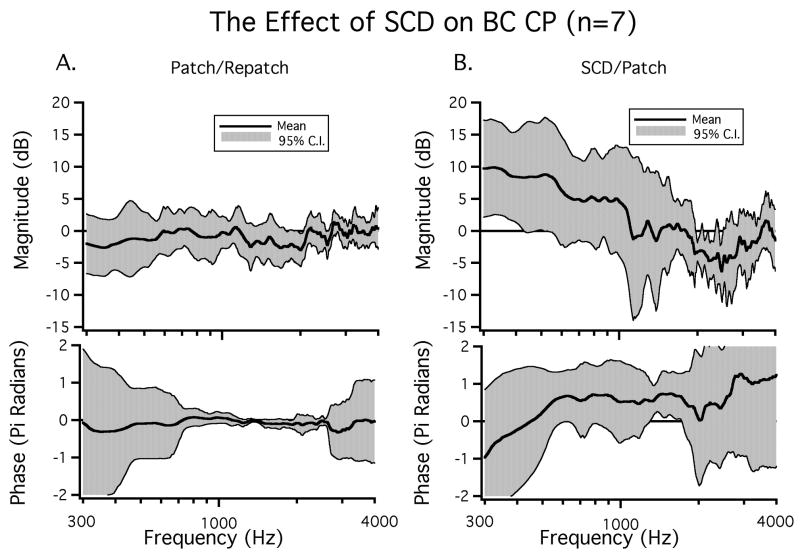

In seven ears we evaluate the bone-conduction evoked CP while repeatedly patching and unpatching the hole. The difference between the patched and the repatched condition was evaluated to determine the reversibility of the hole-induced effects. We chose to evaluate the patch-unpatch-repatch condition because these comparisons exhibited the greatest stability over time and across animals as discussed in the methods section. Figure 3 illustrates data from the SC-hole open and re-patched states in an example ear. In this ear introducing a SC hole resulted in a low-frequency increase in CP in response to BC stimuli for frequencies below 800 Hz. This ear also exhibited a decrease in CP for some frequencies above 1000 Hz. Repatching the SC-hole returned the CP to close to the value seen in the initial patched condition over the entire frequency range. Thus, the effects of unpatching the SCD were reversed by repatching. In order to evaluate the reversibility of SC-hole opening on BC-CP, we calculate the mean dB difference in magnitude (20 log10(repatched / patched)) as well as the difference in phase between the patched and the repatched states in the seven included ears. The mean dB difference illustrated in Figure 4A was near zero over the measured frequency range and was not statistically different from zero at any frequency. The near zero mean and the small 95% confidence interval around the mean of +/- 3 dB are consistent with stability between the patched and repatched states, as well as the reversibility of the effects of SC opening. Additionally, there were no statistically significant changes in phase angle between the patched and the repatched states.

Figure 4.

The mean change in BC-CP between A) the patched and repatched conditions and B) the SCD open and patched conditions. The 95% confidence intervals as well as the means for both magnitude and phase are plotted (n=7). The large 95% confidence intervals around the phases in Figure 4A at low and high frequencies are, in part, due to uncertainties in phase unwrapping at the lowest and highest frequencies.

The change in BC-CP between the SC hole-open and patched conditions in the same seven ears is presented as a dB difference in magnitude (20 log10(SCDopen / SCDpatched)) in Figure 4B. There was a mean increase in CP as a result of SC opening for frequencies below 1000 Hz. This increase had a maximum near 300 Hz, which was near 10 dB and was statistically significant (p < 0.05). In addition to the change in CP magnitude, there was a mean phase lead for frequencies between 400 Hz and 4000 Hz that was statistically significant for a small frequency range (1500 Hz - 1800 Hz). For frequencies above 2000 Hz the 95% confidence interval (CI) was almost 2π radians. Errors in unwrapping the rapidly varying phase of the bone-conducted CP relative to stimulus volts (Figure 3) may contribute to this large CI; regardless, the data of Figure 3 suggest that introducing an SCD can introduce high frequency phase changes of more than a cycle.

3.1.2 Combination of BC-CP Results

CP measurements in response to BC stimuli were made in 13 additional ears (Songer et al., 2004). In these ears there was a mean increase in CP across the observed frequencies after the introduction of an SC hole (Figure 5). This increase was largest at frequencies below 1000 Hz and was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for frequencies between 300 - 800 Hz, 1300 - 1700 Hz, and 3600 - 4000 Hz. We performed a two-sample t-test to determine if the data from the 13 ears in this section could be pooled with the data from the seven ears in which reversibility was assessed. We found that for frequencies between 300 Hz and 1600 Hz the two data sets were not statistically separable and could be considered to be from the same population.

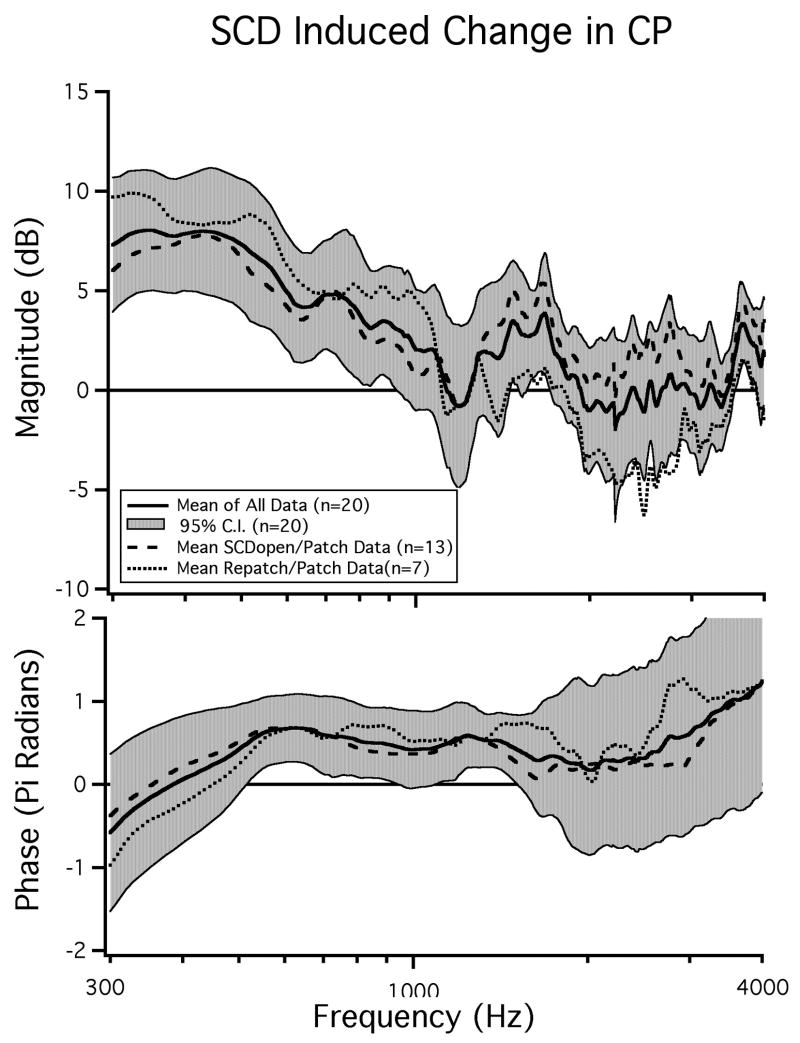

Figure 5.

The effect of SCD on bone-conducted cochlear potential (n=20). The mean CP from seven ears in which reversibility was established as well as the mean CP from 13 ears in which reversibility was not determined are shown. The mean and 95% confidence interval of the pooled data is also illustrated.

Besides the similarities noted above, there were differences between the two data sets (Figure 5) at higher frequencies that may be due to variations in the state of the middle-ear cavities (one bulla-hole open versus two open holes) producing shifts in the frequencies of the bulla cavity anti-resonance. The SCD-induced phase change was similar across the two sets of data.

Pooling the data from the two studies allows us to look at SC-hole-induced changes in BC-CP in a population of twenty ears as illustrated in Figure 5. The combined data reveal a 3 to 8 dB increase in CP magnitude for frequencies below 1000 Hz in both the overall population mean and in the means for the two individual populations. The increase in CP is statistically significant between 300 Hz and 800 Hz (p < 0.05). For frequencies above 300 Hz there is a mean phase lead observed in the SCD open state of near π/2 that is statistically significant between 400 Hz and 900 Hz as well as between 1100 Hz and 1300 Hz.

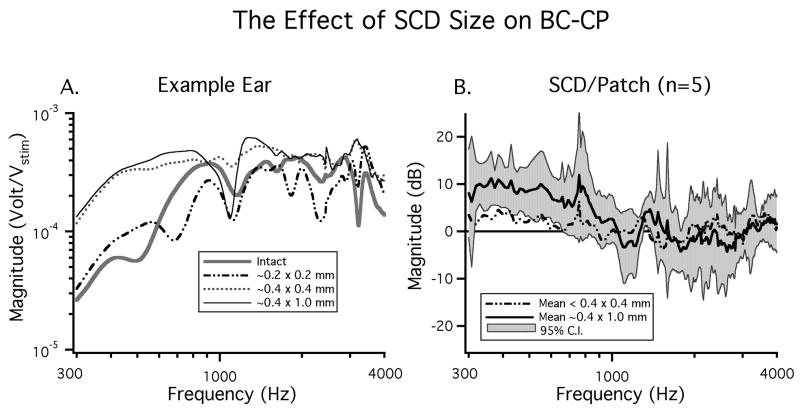

3.2 The Effect of Dehiscence Size

In the previous section all of the SC holes evaluated were large (at least 0.4 mm in diameter and 1 mm in length). In five of the twenty ears discussed above we also evaluated the effect of small SC holes (< 0.4 mm diameter and < 0.4 mm in length). Figure 6A shows CP magnitude data from an example ear in which multiple SC hole sizes were evaluated. In this ear a dehiscence of 0.2 mm in diameter resulted in small changes in the measured CP: a slight low-frequency increase and a decrease in mid-frequencies. Enlarging the dehiscence to 0.4 mm in diameter (the diameter of the boney canal) led to a larger increase in CP magnitude at frequencies < 1000 Hz. Further enlargement of the dehiscence to 0.4 mm by 1.0 mm resulted in little additional change in the low frequency CP. This indicates that dehiscence size effects auditory sensitivity and suggests that there is a saturating effect as dehiscences get very large.

Figure 6.

The effect of dehiscence size on CP in response to bone conducted sound stimuli. A) CP in response to three different dehiscence sizes in an example ear. B) the mean effect of SCD size on BC-CP (n=5).

Figure 6B illustrates the mean effect (n = 5) of a large (0.4 mm × 1.0 mm) and small (<0.4 mm × <0.4 mm) SC hole on CP in response to BC stimuli. In the five ears that we tested the large SC hole (A > 0.13 mm2) led to a mean increase in CP of nearly 10 dB above the dehiscence patched state, which is statistically significant for frequencies between 300 and 800 Hz (p < 0.05). The smaller dehiscence led to a smaller (3 dB) increase in CP above the patched state in the low frequencies, but this increase was not statistically different from zero at any frequency.

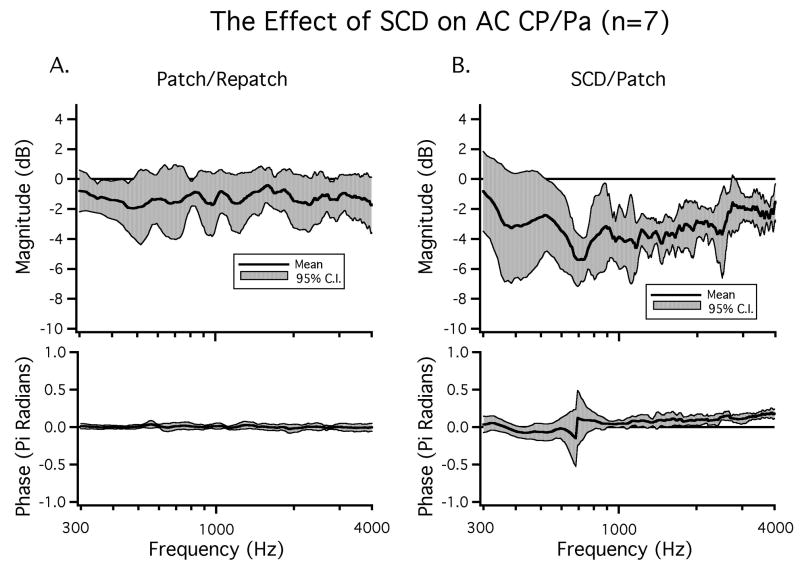

4. Results: SCD and Air-Bone Gap

We evaluated the effect of an SC hole on CP in response to both BC and AC stimuli in the same seven ears, allowing us to compute an SCD-induced air-bone gap for each of the chinchillas. The air-bone gap is calculated as the dB difference between the SC-hole-induced change in CP resulting from BC stimuli and the change in CP resulting from AC stimuli. Since the response of AC-CP to a SC hole has been documented previously (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) we only briefly revisit that topic in this study.

4.1 The effect of SCD on AC-CP

While the CP produced by BC stimulation is normalized by the stimulus voltage, the CP in response to AC sound stimuli is normalized by PTM (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) because PTM is considered to be the effective air-conduction stimulus. The effect of SC opening in response to BC (Figure 7A) and AC (Figure 7B) sound stimuli in an example ear demonstrate that opening a patched SCD can evoke a low-frequency decrease in CP in response to AC sound even as a low-frequency increase in CP in response to BC sound is observed. We also see that the SCD-induced changes in the response to both AC and BC stimuli are reversed by patching.

Figure 7.

Changes in CP in response to both AC and BC sound stimuli in an example ear. A) A reversible decrease in low-frequency sensitivity to BC sound is observed. B) A reversible increase in sensitivity to AC sound is observed.

The mean changes in CP in response to AC sound produced by patching and repatching as well as the changes produced by opening the patched SCD in seven ears are illustrated in Figure 8. The mean difference between the patched and repatched state is illustrated in Figure 8A and shows a slight decrease that is fairly constant with frequency and is not statistically different from zero. The difference between the SC hole and the patched state (Figure 8B) illustrates a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease2 in CP between 500 and 4000 Hz. This decrease averages about 4 dB in magnitude.

Figure 8.

The mean change in AC-CP/PTM. A) between the patch and repatch state and B) between the SCD open and the patched state along with the 95% confidence intervals (n=7).

4.2 Air-Bone Gap

The SCD-induced air-bone gap in our chinchilla measurements is defined as the dB difference between the SC-hole induced changes in response to BC (Figure 5) and AC (Figure 8B) stimuli. Figure 9 illustrates a mean air-bone gap of as much as 12 dB for frequencies below 2000 Hz. The air-bone gap is statistically different from zero (p < 0.05) for frequencies between 300 Hz and 900 Hz.

Figure 9.

The mean air-bone gap with the 95% confidence intervals (n=7).

5. Discussion

5.1 Cochlear Potential in Response to BC stimuli

5.1.1 Summary

Our results indicate an increase in sensitivity to BC sound after introducing SC holes in seven ears in which reversibility was established (Figure 4). A similar increase in sensitivity was observed at frequencies less than 1500 Hz in an additional 13 ears in which the effects of an SC hole were evaluated without quantifying reversibility (Figure 5). The differences between the two populations at higher frequencies were small (5 dB on average), but statistically significant. The means from the two populations show a statistically significant low-frequency increase in BC sensitivity as a result of the SC hole (Figure 5). The repeatability and reversibility observed between the patch-unpatch-repatch conditions (n=7) both within and across animals (Figures 3 & 4) are consistent with hearing changes evoked by the mechanical effects of opening and closing the dehiscence and not uncontrolled changes in the sensitivity of the inner ear. The similarity between the mean data collected in the patch-unpatch-repatch conditions (n=7; Figure 4) and that collected in the intact-SC hole state (n=13; Figure 5) suggest the hearing changes in the total population (n=20) are evoked by mechanical effects of opening and closing the dehiscence.

5.1.2 Comparison to Previous Work

The effect of BC stimuli on auditory sensitivity has been evaluated in fat sand rat by Sohmer and his co-workers (Sohmer et al., 2004); they looked at SC-hole-induced changes in click-evoked auditory brain stem responses (ABR) to both AC and BC stimuli and found a statistically significant decrease in ABR threshold in response to BC sound of −7.0 ± 4.2 dB SPL. The methods used by Sohmer et al. do not allow for evaluation of the frequency dependence of this increase in sensitivity on the ABR response. We have argued that patient data and the increase we see in BC sensitivity are evidence for dehiscence-induced changes in cochlear impedances and the trans-cochlear partition sound pressure that results from the introduction of a third-window into the inner ear (Rosowski et al., 2004). Sohmer et al., on the other hand, argue that the increase results from a simplification of the interactions of several modes of BC excitation as a result of SCD, i.e., the SCD eliminates an interfering mode of BC (Sohmer et al., 2004). We will address the potential mechanisms associated with the increase in BC-CP later.

Increased sensitivity to BC sound stimuli after the introduction of a SC hole has previously been reported in humans (Minor, 2000; Watson et al., 2000; Mikulec et al., 2004). In human patients with SCD syndrome, bone-conduction sensitivity below 2000 Hz can be elevated by 5 - 15 dB (Mikulec et al., 2004), such an increase is similar in frequency and magnitude to the results reported here.

5.2 Cochlear Potential in Response to AC stimuli

5.2.1 Summary

Our results indicate that there is a statistically significant decrease in CP, when normalized by the AC sound pressure stimulus (PTM) in response to SCD. This decrease is largest for low frequencies and is reversible with patching (Figure 8).

5.2.2 Comparison to Previous Work

In this and a previous study (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) we have observed reversible decreases in CP in response to AC stimuli, but previous work in fat sand rat has failed to show changes in ABR response to AC clicks (Sohmer et al., 2004). That study found an increase in threshold (decreased sensitivity) of 1.4 ± 4.8 dB SPL that was not statistically significant. One potential reason for this difference is that Sohmer et al. used broad-band clicks with little low-frequency energy. Most of the changes we observe are at low-frequencies where the Sohmer et al. measurements were least sensitive (Songer and Rosowski, 2005). Other potential reasons for the different result include: inter-species variation, and a lack of control of the state of the middle-ear muscles in the sand rat study.

In patients with SCD syndrome a decrease in sensitivity to low-frequency AC sound stimuli is frequently observed (Minor, 2000; Watson et al., 2000; Minor et al., 2003; Mikulec et al., 2004; Limb et al., 2006). In this study and our previous studies (Songer and Rosowski, 2005) we observe a decrease in CP in response to AC sounds that is largest between 500 and 1000 Hz. Below 500 Hz the decrease is not as significant. The decrease in air-conducted hearing sensitivity in chinchilla for frequencies below 500 Hz is different from humans where the largest hearing loss is often at 250 Hz. One reason for this difference may be the large SCD-induced decrease in middle-ear input admittance in the chinchilla observed in this frequency range (Songer and Rosowski, 2006). These admittance changes cause significant decreases in PTM that reduce the change in CP/PTM. While SCD is also known to affect the sound-induced motion of the human stapes and TM (there are changes in sound-induced ossicular velocity in human ears with SCD, e.g., Chien et al. (2007); Rosowski et al. (2008)) these changes are relatively small. Another factor is that while the decreases observed in chinchilla in response to AC sounds are smaller than those observed in humans with measurable hearing loss; not all SCD patients exhibit a hearing loss.

5.3 Air-Bone Gap

5.3.1 Summary

In this study we evaluated the SC-hole-induced air-bone gap in seven chinchilla ears in which reversible effects of SC opening were observed in response to both AC and BC sounds. Our results indicate an air-bone gap in chinchilla for frequencies below 1000 Hz. This air-bone gap is largest at the lowest frequencies with a mean of near 12 dB and is affected by the increased sensitivity to BC stimuli and the decreased sensitivity to AC stimuli.

5.3.2 Comparison to Previous Work

Sohmer and coworkers evaluated the effect of SC opening on auditory sensitivity to both AC and BC clicks and concluded that the SC hole only had a significant effect on responses to BC clicks (Sohmer et al., 2004). Their reported values of a mean increase in sensitivity to BC clicks of 7.0 dB and a mean decrease in sensitivity to AC clicks of 1.4 dB, lead to an estimated air-bone gap of 8.4 dB.

Air-bone gaps have been also been reported in many patients with SCD syndrome. Air-bone gaps of 24±7 dB for frequencies between 250 and 4000 Hz (Minor et al., 2003) and a mean air-bone gap of 37 dB at 500 Hz (Mikulec et al., 2004) have been reported. The air-bone gap we report here for chinchilla (12 dB) is smaller than that observed clinically. This is mainly due to the smaller changes in sensitivity to AC stimuli as a result of the SC opening in chinchillas compared to that observed in patients as discussed above. Interspecies variation is one potential reason for the difference in magnitude of the air-bone gap. Other differences are: 1) the SC hole in chinchilla opens into an air-filled middle-ear air space whereas the SCD in human patients opens into the cranial cavity (dura and cerebral spinal fluid), and 2) the middle-ear dynamics in humans are dominated by the stiffness of the TM and ossicular ligaments while in chinchilla those stiffnesses are small and middle-ear dynamics appear to be dominated by the inner ear (Rosowski et al., 2006).

In calculations of air-bone gaps in human patients, clinicians frequently don't test for super-sensitivity to BC sound stimuli resulting in underestimates of the air-bone gap in cases of SCD, and potentially missing an important clue to the etiology of the gap. Our data suggest that for patients with SCD syndrome, important information can be obtained by fully exploring the sensitivity to both AC and BC sound stimuli. Specifically, increased sensitivity to BC stimuli may be a useful sign in the differential diagnosis of SCD syndrome and otosclerosis (Mikulec et al., 2004). In both of these situations patients may present with a conductive hearing loss defined by an air-bone gap; however, patients with SCD syndrome may be super-sensitive to BC stimuli whereas patients with otosclerosis are not.

5.4 The effect of dehiscence size

The data of Figure 6 demonstrate that the magnitude of the effect of an SC hole, or dehiscence, on bone conduction generated CP depends on the size of the dehiscence. Small dehiscences (of an area < 0.03 mm2) have little effect on the BC-CP, and larger dehiscences have larger effects. Although once the dehiscence area reaches 0.13 mm2 (a diameter of 0.4 mm) further increases in dehiscence size produce little additional increase in BC-CP. A similar range of sensitivity changes (but of opposite sign) as well as saturation of the size effect were predicted for SCD induced changes in AC-CP by a model of SCD in air conduction. The predicted saturation of the effect occurred when the SCD area approximated the cross-sectional area of the SC (∼0.13 mm2). We interpret this saturation in the following manner: When the dehiscence is smaller than the SC canal cross-section, the dehiscence area limits the magnitude of the volume-velocity shunted from the vestibule through the canal. When dehiscence area is equal to or larger than the SC canal cross-section, the canal remnant limits the shunted volume velocity and further increases in dehiscence area (e.g. by lengthening the dehiscence) produce only small effects on both the magnitude of the shunted volume velocity and further changes in the ears sensitivity (Songer and Rosowski, 2007). The similar size dependence we see in BC-CP suggests that a similar mechanism limits the effect of dehiscence size on BC-CP.

5.5 Mechanism of SC Hole-Induced Air-Bone Gap

An air-bone gap is typically indicative of conductive hearing loss due to middle-ear pathology such as otosclerosis. We hypothesize a pathological ‘third window’ mechanism as the cause of the air-bone gap and apparent conductive hearing loss induced by SCD. As stated in the introduction, the pathological third window hypothesis has been used to explain the qualitative changes in auditory sensitivity, both in response to AC and BC sound stimuli, resulting from a SC hole or dehiscence (Minor et al., 1998; Rosowski et al., 2004; Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2006).

In response to AC sound stimuli the surgically or pathologically induced dehiscence is expected to introduce an additional fluid pathway for sound energy to flow out of the inner ear. This pathological fluid pathway shunts volume velocity away from the inner ear resulting in decreased sensitivity to AC stimuli as well as a decrease in cochlear load and increases in ossicular velocity (Songer and Rosowski, 2006). The physiologic measurements of SCD induced decreases in AC-CP, coupled with increases in middle-ear input admittance and stapes velocity in response to AC sound stimuli reported in this paper and previously (Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2006) are all consistent with such a mechanism. Also, all of these data are well fit by a model of chinchilla AC responses that includes an SCD ‘shunt’ mechanism that acts to reduce the volume velocity of the stapes delivered to the cochlear input (Songer and Rosowski, 2007).

In response to BC sound stimuli the dehiscence is also expected to introduce a pathological fluid pathway that shunts volume velocity away from the cochlea leading to a decrease in the impedance on the scala vestibuli side of the cochlear partition. This decrease in impedance on one side of cochlea could lead to an increased pressure difference across the cochlear partition, and a resultant increase in the sensitivity to bone-conducted sounds, though such a result would depend on the normal cochlear response to BC resulting from a difference of two nearly equal sound pressures on either side of the cochlear partition. In such a ‘balanced’ normal situation, the trans-cochlear sound pressure would be increased if the sound pressure in the cochlear vestibule was reduced by the action of an SCD shunt.

The physiologic data presented in this paper as well as that presented previously (Songer et al., 2004; Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2006) are consistent with the qualitative predictions of the pathological third window hypothesis. This consistency is further supported by the correlation between (a) our data describing graded changes in BC-CP sensitivity with the size of the dehiscence and (b) model predictions of effect of dehiscence size on the shunting of sound from the vestibule by a dehiscent SC (Songer and Rosowski, 2007).

We have noted earlier that Sohmer and his coworkers presented an alternate explanation for the SCD associated increase in cochlear sensitivity that they recorded in sand rats (Sohmer et al. 2004), which they suggest is related to a modulation of the interaction of different bone-conduction pathways. Some incidental findings from our study do support such interactions, but do not contradict our own interpretation. In this study measurements of PTM in response to AC sound were made to enable us to normalize the measured CP by the acoustic stimulus. We did not remove the sound source while making measurements of CP in response to BC sound stimuli, and we generally observed an induced PTM in response to BC sound stimuli. Furthermore the magnitude of the BC induced PTM was generally observed to increase after SCD. This increase was statistically significant for frequencies below 1000 Hz with a mean near 5 dB and was reversible with patching. Such an increase is not consistent with the expected decrease in vestibule sound pressure predicted by the third-window hypothesis but could result from the SCD affecting multiple bone-conduction paths, e.g. tympano-ossicular compression, or ossicular and fluid inertance. Further study of this phenomena may provide insight into the varied mechanisms associated with bone conduction and their interactions.

5.6 Clinical Implications

Patients with SCD syndrome may present with a conductive hearing loss. In this study we have demonstrated that the introduction of a dehiscence causes an apparent conductive hearing loss in chinchilla as evidenced by a statistically significant low-frequency air-bone gap. The reversibility of this air-bone gap by patching the dehiscence implies that the air-bone gap in patients suffering from SCD syndrome may resolve after surgical patching as has been seen in a number of surgical cases (Mikulec et al. 2005; Limb et al. 2006) and in temporal bone experiments (Chien et al., 2007). We have also presented physiologic evidence that dehiscence size can effect sensitivity to BC stimuli: small dehiscences result in small changes in auditory sensitivity and larger dehiscences result in larger changes in auditory sensitivity. However, our results and the earlier predictions of a model of SCD in air-conducted sound (Rosowski and Songer 2007) suggest that once the dehiscence area approximates the cross-sectional area of the SC canal, further increases in dehiscence area produced little additional change in the sensitivity to either AC or BC conducted sound. The earlier model also suggests small changes in the SC shunting that depend on the location of the dehiscence in the SC: Dehiscences closer to the vestibule are predicted to have slightly larger effects on hearing sensitivity than dehiscences that are more distant from the vestibule.

6. Conclusions

Our physiological data support the action of the SCD as a pathological third inner-ear window in chinchilla, where the window enhances the response to bone-conducted stimuli and decreases the response to air conduction. The BC enhancement is consistent with an SCD-shunt induced reduction in the sound pressure within the vestibule that increases the sound-pressure difference across the basilar membrane over the difference present without the SCD. The AC decrease is a result of shunting of air-conducted sound energy away from the cochlea (Songer and Rosowski, 2005, 2007). The results in chinchilla are qualitatively similar to those seen in human patients with SCD syndrome, specifically the low-frequency air-bone gap.

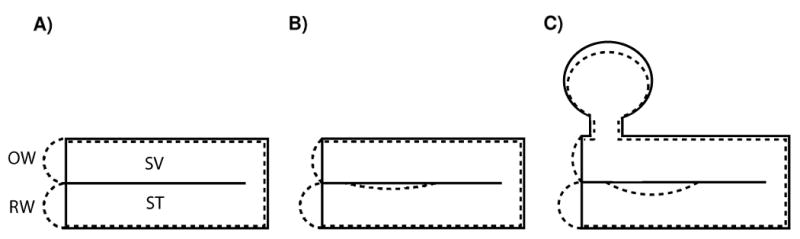

Figure 1.

Cochlear partition response to compressional bone conducted sound if A) the RW and OW are of equal impedance, B) the RW and OW have different impedances, C) the fluid volume of the vestibule and semicircular canals is taken into consideration. Note that the largest cochlear partition motion is in response to greatly different impedances between the SV and ST. The solid lines in the figure represent the normal state of the inner ear and the dashed lines represent the compressed inner ear. Adapted from Békésy Figure 6-17(Békésy, 1960, p.145).

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by an NSF graduate student fellowship, NIH training grant T32-DC00038, and an additional NIH research grant R01-DC000194. S. Merchant and W. Peake, and M.E. Ravicz provided insights and suggestions. M. Wood assisted with data collection and animal surgery.

Footnotes

Contributing author: Jocelyn Songer, Eaton-Peabody Laboratory of Auditory Physiology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, 243 Charles St., Boston, MA, 02114. jocelyns@mit.edu

The presence of other normal ‘third-windows’ has been suggested (Ranke, 1953; Tonndorf, 1972), but the contribution of inner-ear compressibility or other fluid paths into the cochlear to hearing mechanics has been generally considered to be small (Wever and Lawrence, 1950; Shera and Zweig, 1992; Voss et al., 1996; Gopen et al., 1997).

The CP/PTM results here are consistent with those reported previously (Songer and Rosowski, 2005). Note, however, that the CP/PTM results show smaller low frequency changes in response to air-conducted sound stimuli than those reported as CP/Pstim. These differences are attributed to SCD-induced changes in middle-ear input admittance (Songer and Rosowski, 2006) that are associated with changes in the PTM produced by constant voltage stimuli to the ear phone.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Békésy Gv. Experiments in hearing. Acoustical Society of America 1960 [Google Scholar]

- Brantberg K, Bergenius J, Mendel L, Witt H, Tribukait A, Ygge J. Symptoms, findings and treatment in patients with dehiscence of the superior semi-circular canal. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;121:68–75. doi: 10.1080/000164801300006308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey JP, Minor LB, Nager G. Dehiscence or thinning of bone overlying the superior semicircular canal in temporal bone survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:137–147. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien W, Ravicz ME, Rosowski JJ, Merchant SN. Measurements of human middle- and inner-ear mechanics with dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Otol Neurotology. 2007;28:250–257. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000244370.47320.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Visualizing Data. Hobart Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer PD, Minor LB, Carey JP, Santina CC. Eye movements in patients with superior canal dehiscence syndrome align with the abnormal canal. Neurology. 2000;55:1833–1841. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S, Sichel J, Sohmer H. Bone conduction experiments in animals- evidence for a non-osseous mechanism. Hearing Research. 2000;146:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopen Q, Rosowski JJ, Merchant SN. Anatomy of the normal cochlear aqueduct with functional implications. Hearing Research. 1997;107:9–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen TP, Carey JP, Liang C, Minor LB. Superior canal dehiscence: Mechanisms of pressure sensitivity in a chinchilla model. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1331–1336. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.11.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limb CJ, Carey JP, Srireddy S, Minor LB. Auditory function in patients with surgically treated superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Otol & Neurotol. 2006;27:969–980. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000235376.70492.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulec AA, McKenna MJ, Ramsey MJ, Rosowski JJ, Herrmann BS, Rauch SD, Curtin HD, Merchant SN. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence presenting as conductive hearing loss without vertigo. Otology and Neurotology. 2004;25:121–129. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulec AA, Poe DS, McKenna MJ. Operative management of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:501–507. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000157844.48036.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor LB. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Am J Otol. 2000;21:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor LB, Carey JP, Cremer PD, Lustig L, Streubel SO. Dehiscence of bone overlying the superior canal as a cause of apparent conductive hearing loss. Otology and Neurotology. 2003 doi: 10.1097/00129492-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor LB, Solomon D, Zinreich J, Zee DS. Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:249–258. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranke O. Physiologie des Gehörs. In: Ranke O, Lullies H, editors. Gehör-Stimme-Sprache. Berlin: Springer; 1953. pp. 3–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ. Invited comment on “when an air-bone gap is not a sign of middle-ear conductive loss” by Sohmer et al. Ear and Hearing. 2009;30:149–150. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318192769f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Nakajima HH, Merchant SN. Clinical utility of laser-Doppler vibrometer measurements in live normal and pathologic human ears. Ear and Hearing. 2008;29:250–257. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31815d63a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Ravicz ME, Songer JE. Structures that contribute to middle-ear admittance in chinchilla. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192(12):1287–1311. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Songer JE, Nakajima HH, Brinsko KM, Merchant SN. Investigations of the effect of superior semicircular canal dehiscence on hearing mechanisms. Otology and Neurotology. 2004;25:323–332. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA, Zweig G. An empirical bound on the compressibility of the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 1992;92:1382–1388. doi: 10.1121/1.403931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohmer H, Freeman S, Geal-Dor M, Adelman C, Savion I. Bone- conduction experiments in humans- a fluid pathway from bone to ear. Hear Res. 2000;146:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohmer H, Freeman S, Perez R. Semicircular canal fenestration- improvement of bone- but not air- conducted auditory thresholds. Hear Res. 2004;187(1-2):105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE. Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology, Division of Health Sciences and Technology. Cambridge, MA: MIT; 2006. Superior canal dehiscence: Auditory mechanisms. PhD: 159. [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE, Brinsko KM, Rosowski JJ. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence and bone conduction in chinchilla. In: Gyo K, Wada H, Hato N, Koike T, editors. The proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Middle Ear Research and Oto-Surgery. World Scientific; 2004. pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE, Rosowski JJ. The effect of superior canal dehiscence on cochlear potential in response to air-conducted stimuli in chinchilla. Hear Res. 2005;210:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE, Rosowski JJ. The effect of superior-canal opening on middle-ear input admittance and air-conducted stapes velocity in chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2006;120(1):258–269. doi: 10.1121/1.2204356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE, Rosowski JJ. A mechano-acoustic model of superior canal dehiscence in chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2007;122:943–951. doi: 10.1121/1.2747158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenfelt S, Goode R. Transmission properties of bone conducted sound: measurements in cadaver heads. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2005;118:2373–2391. doi: 10.1121/1.2005847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonndorf J. Bone conduction. In: Tobias JV, editor. Foundations of Auditory Theory. II. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- Voss SE, Rosowski JJ, Peake WT. Is the pressure difference between the oval and round windows the effective acoustic stimulus for the cochlea? J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;100(3):1602–1616. doi: 10.1121/1.416062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SRD, Halmagyi GM, Colebatch JG. Vestibular hypersensitivity to sound (Tullio phenomenon: Structural and function assessment. Neurology. 2000;54:722–728. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.3.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever EG, Lawrence M. The acoustic pathway to the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 1950;22:460–467. [Google Scholar]