Abstract

Disclosure of HIV seropositive results among HIV-discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa is generally low. We describe a facilitated couple counselling approach to enhance disclosure among HIV-discordant couples.

Using unique identifiers, 293 HIV-discordant couples were identified through retrospective linkage of married or cohabiting consenting adults individually enrolled into a cohort study and into two randomized trials of male circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. HIV discordant couples and a random sample of HIV-infected concordant and HIV-negative concordant couples (to mask HIV status) were invited to sensitization meetings to discuss the benefits of disclosure and couple counselling. HIV-infected partners were subsequently contacted to encourage HIV disclosure to their HIV uninfected partners. If the index positive partner agreed, the counsellor facilitated the disclosure of HIV results, and provided ongoing support. The proportion of disclosure was determined.

81% of HIV-positive partners in discordant relationships disclosed their status to their HIV-uninfected partners in the presence of the counsellor. The rates of disclosure were 81.3% in male HIV-positive and 80.2% in female HIV-positive discordant couples. Disclosure did not vary by age, education or occupation.

In summary, disclosure of HIV-positive results in discordant couples using facilitated couple counselling approach is high, but requires a stepwise process of sensitization and agreement by the infected partner.

Keywords: HIV disclosure, Facilitated couple counselling, Discordant couples

Background

Couple HIV-discordance in sub-Saharan Africa is high; with prevalence rates ranging from 3% to 20 % in the general population to over 60% among HIV infected married or cohabiting individuals (Carpenter, L.M., et al, 1999; De Walque, D., 2006; Guthrie B.L, De Bruyn G. & Farquhar, C., 2007; Lurie, M.N., et al, 2003; McKenna, S.L., et al, 1997; Tanzania Government and ORC Macro., 2005). HIV transmission among discordant couples is substantial, ranging from 5.0 to 16.7 per 100 person years (Gray, R.H., et al, 2000; Gray, R.H., et al 2001; Hira, S. K., et al, 1997; Hugonnet, S. et al, 2002; Quinn, T.C., et al, 2000; Senkoro, P.K., et al., 2000; Serwadda, D., et al, 1995), which is 5 to 17 times higher than incidence among HIV concordant negative couples. Thus, couple HIV discordance considerably contributes to the HIV epidemic and represents an unmet HIV prevention need in sub-Saharan Africa. However, less than 10% of HIV sero-positive individuals know their partners’ status and only about 20% of HIV discordant couples know that they are living in a discordant relationship in East Africa (Tanzania Government and ORC Macro., 2005; Bunnell, R., et al, 2008). The lack of knowledge of partner HIV status poses an increased risk of HIV transmission to the uninfected partners (Carpenter, L.M., et al, 1999; Serwadda, D., et al, 1995) and may lead to unprotected sex if the HIV infected partner incorrectly assumes that their sexual partners are also HIV infected. HIV infected individuals may have difficulty disclosing their HIV sero-status to their sexual partners (Sullivan, M.K., 2005) or they may disclose incorrect HIV results to their HIV uninfected partners for fear of blame, violence and marital dissolution.

HIV disclosure to sexual partners is an important HIV prevention strategy (Medley. A., et al, 2004; UNAIDS, 2000), and is associated with a reduced risk of HIV transmission by 18% to 41% (Pinkerton, D.S., & Galley, L.C., 2007) and increased use of condoms from 4% to 57% (Allen, S., et al, 1992). Appropriate counselling approaches to facilitate HIV positive persons in discordant relationships to disclose their status to their HIV-uninfected partners is thus central to HIV prevention in couples. We describe a stepwise strategy to promote disclosure of HIV-positive results among discordant couples using a facilitated couple counselling approach in Rakai district, Uganda.

Participants & Methods

Eligible couples were identified from three studies conducted by the Rakai Health Sciences Programme: (1) the Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS); a prospective population-based surveillance study, which obtains annual data from approximately 14,000 men and women aged 15–49, resident in Rakai communities. (2) A randomized trial of male circumcision for HIV/STD prevention which enrolled 5000 uncircumcised HIV-negative men who accepted voluntary HIV counselling and testing (VCT); and (3) a randomized trial of male circumcision which enrolled 997 HIV-positive men. Female partners of men enrolled in the circumcision trials were invited to enrol into a parallel study.

Participants were informed of procedures, benefits and risks of the study in which they were enrolled, and provided written informed consent for interviews and blood sample collection. All individuals were provided with health education on HIV prevention and safe sex practices, were offered condoms and individual and couples VCT free of charge. The studies were approved by the Science and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute (Entebbe, Uganda), the Committee for Human Research at Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health (Baltimore, MD, USA), and the Western Institutional Review Board (Olympia, WA, USA), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, the body that oversees all medical research in Uganda.

Interviews and blood collection were conducted in private by same sex interviewers to obtain socio-demographic, health and behavioural data. For participants who were currently married or cohabiting, we requested information on their partners and retrospectively linked them to identify HIV concordantly positive or negative and HIV-discordant couples. Couples were invited to attend couple meetings at the counsellor’s office in their respective communities. The invitation letters were sent to all 293 HIV-discordant couples identified, as well as randomly selected concordant HIV-infected (n = 22) and uninfected couples (n = 22) in the same communities. The concordant couples were included to mask the discordant couples’ HIV status and avoid breach of confidentiality. Attendance was extremely high, with 100% being represented by at least one partner and reasons for the other partner not present in the meeting were given by the attending partner and include: away business/official duties, away burial and away hospital among others. The attending partner assured the authors of his/her commitment to inform the absentee partner about the details of the meeting.

During the sensitization meetings, the following issues/topics were discussed: HIV sero-discordance, the benefits of HIV disclosure and couple counselling and partner communication (see table 1 for detailed outline). Couples were also informed of the availability of free HIV care and antiretroviral therapy offered by the Rakai Health Sciences Programme with funding from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). After the couples’ meetings, participants were followed up either at home or at the counsellor’s office to facilitate HIV disclosure and couple counselling. For the HIV-discordant couples, the counsellor first met with the HIV- positive partner and, subject to his/her agreement, the counsellor met with the HIV-negative partner and then scheduled a meeting with the couple where both partners disclosed their results to one another in the presence of the counsellor. If one of the partners refused to share their HIV result, a record of non-disclosure was recorded.

Table 1.

Sample session Plan for HIV Discordant & Concordant Couples’ Sensitization Outline

|

Subject: Couple Sensitization Session for HIV Discordant & Concordant Couples Date: Time: |

Lead Counsellor: |

| Co-Lead Counsellor: | |

Participants are engaged in:

| |

|

Pre-Session: (Time: 20 – 30 minutes) The Counsellors warmly welcomes participants into the Hall, provides them with seats and begins by introducing him/her self and other Rakai Program staff if available Counsellor proceeds on by requesting participants to introduce their neighbours (Via pre-determined format) Counsellor solicits for ground rules and expectations from participants Counsellor displays the chart with the session objectives of the session | |

| Objective | Duration | Content | Teaching Method | Teaching Aids/materials | Participants/Learners activity | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing participants share individual experiences with regard to VCT | 30 min | Participants share the individual experiences regarding VCT and the lessons learned from this endeavour. The facilitator moderates the exercise | Experience sharing/story telling | Active Listening | Asks questions | |

| Mention at least 4 benefits of couple HIV counselling & testing | 20 min |

|

Small Group discussion | Flip Chart | -Asking Questions Answering Questions -Brainstorming |

Ask a participant to summarize all points presented. |

| 20 min | BREAK- BREAK –BREAK- BREAK- BRAK- BREAK- BREAK- BREAK- BREAK- BREAK- BREAK –BRAK- BREAK- BREAK | |||||

| Explain the cardinal elements of effective communicat ion among couples | 20 min | Good communication is the first step in problem solving and in relation building:

|

Small group discussion then counsellor corrects myths | Flip Chart | Asking Questions Answering Questions -Brainstorming |

Asks questions |

| List at least 8 reasons why spouses fail to communicate effectively | 25 min |

|

Small group discussion then counsellor corrects myths & misconceptions in the groups | Flip Chart | Asking Questions Answering Questions -Brainstorming |

Asks questions |

| Outline at least five benefits of effective communication in couples | 15 min | 1. Good communicators avoid misunderstandings, unacceptable behaviours, fights and separation 2. Good communicators can disagree, yet agree respectfully and constructively 3. Good communicators know when and how to talk, and when and how to listen.4. Good communicators resolve problems through discussion and constructive arguing. 5. Good communication promotes sharing, companionship, and bonding 6. Good communicators engage in frank discussions that reveal each person’s needs/desires/agenda and develop a clear understanding of how to fulfill each other’s expectations | Small group discussion then counsellor corrects myths and misconceptions | Flip Chart | Asking Questions Answering Questions -Brainstorming |

Asks questions |

| Describe the salient issues regarding Couple HIV discordance | 30 min |

|

Small group discussions then counsellor corrects myths and misconceptions | Flip Chart | Asking Questions Answering Questions -Brainstorming |

Asks questions |

| Rapping up the session | 10 min | Counsellor appoints one or two participants to summarize the whole session. Then counsellor appreciates all participants for their presence and active participation | - | Summative evaluation | ||

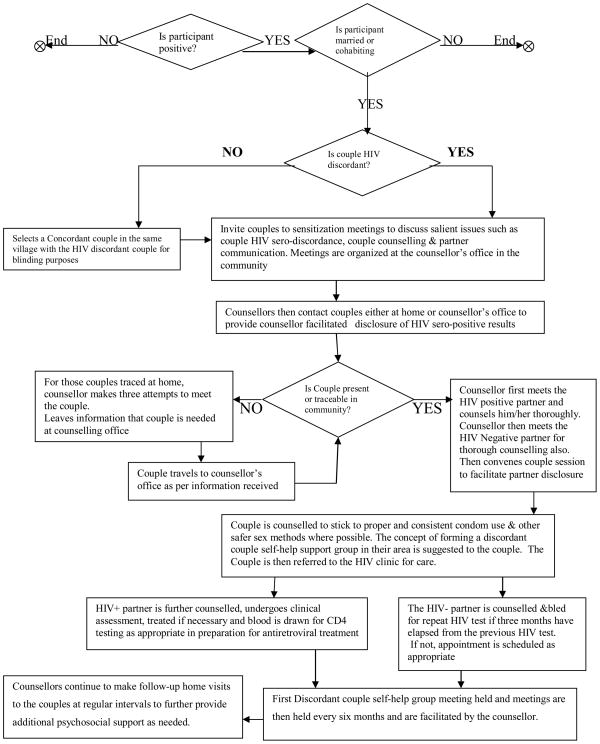

After disclosure (for couples that accepted), the counsellor conducted a 45–60 minute couple counselling session to help the couple understand the implications of each other’s HIV status and map out new strategies for the future. The counsellor provided the couple with free condoms and encouraged them to collect more condoms from the Rakai Health Sciences Programme condom distribution outlet sites in the community in case they needed more supplies. Every HIV-infected individual who accepted disclosure and facilitated couple counselling was referred to the HIV clinic for on-going counselling and clinical management (CD4 screening, treatment for opportunistic infections and initiation of antiretroviral therapy if eligible) and their HIV-negative partners were counselled and provided with repeat HIV testing as appropriate (see figure 1 for detailed profile).

Figure 1.

Profile of activities during facilitated couple counselling and HIV sero-status disclosure among concordant & discordant couples and related services provided.

Also, after the disclosure and couple counselling session, the idea of forming an HIV self-help sero-discordant couple group in the community was suggested to the couple. If the couple agreed, a letter of invitation was handed to them detailing the agenda, date, time and venue of the self-help sero-discordant couple group meeting. There are currently ten such groups in the Rakai Health Sciences Programme communities and membership is open to new qualifying couples in the Rakai Health Sciences Programme cohort. Every group is led by two counsellors who facilitate group sessions as planned. Counsellors were sufficiently trained in group psychotherapy skills. The groups meet every six months to discuss, review and evaluate coping strategies and devise new plans. Each group developed its own contract (verbal ground rules) with the counsellors and during the sessions, individuals freely share experiences among themselves and discuss disputes and challenges that arise in their day-to-day living and the counsellors provide group leadership, direction and support (see table 2 for detailed outline). After every group session, counsellors make a follow-up of every member individually and as a couple either at home or at the counsellor’s office to discuss their feelings about the group and also as a follow-up on couple relational issues and provide additional support as needed.

Table 2.

Establishing Discordant Couple Self-help Groups in Rakai, Uganda.

| Rationale |

| • To reduce myths and misinformation about the realities of couple HIV discordance, mitigate associated stigma and discrimination, and consequently improve self esteem and coping strategies among discordant couples. |

| Objectives |

| • To provide opportunity for fellowship and peer support. |

| • To provide opportunity for the negative partners to get information on risk reduction and address questions on couple HIV discordance. |

| • To provide forum where discordant couples can share experiences and challenges |

| • To help discordant couples develop ability to communicate accurate empathic understanding skills in marriage and family. |

| Anticipated Benefits |

| • Experiences will be shared with other members of the community and belonging will be cultivated. |

| • Group cohesiveness & Universality (all clients share the same problem and this is both supportive and therapeutic) |

| • Feedback will be shared among client’s themselves. |

| • Destructive criticism is unlikely |

| • The feelings of powerlessness which many people experience when they are sick/infected will be overcome as a result of the therapeutic effects of group membership |

| • Will allow clients to act as both clients and therapists |

| • Corrective emotional experiences (Clients who have been defensive and guarded will be encouraged to share their feelings with others and in doing so will become more self-confident and self-accepting) |

| • Imitative Behaviours (Clients will also learn from one another through observations and modelling and new ideas and attitudes will be explored and nurtured through group interaction.) |

| Requirements for Becoming a Member |

| • Discordant the last time they received their HIV results and know the status of one another |

| • Willing to continue participating in couple meetings regularly or as convened |

| • Willing to share with peers issues regarding HIV disclosure/discordance challenges and coping strategies |

| • Willing to respect Human rights and Human dignity of their partners |

| • Willing to provide support to either partner as necessary |

| • Willing to explore and implement realistic and concrete risk reduction steps/strategies |

| • Willing to keep and maintain confidentiality of all issues discussed in the group and abide by the restrictions of shared confidentiality |

| Counsellor/Group Leader roles |

| Beginning sessions |

| • Helping members get acquainted |

| • Setting a positive tone |

| • Clarifying the purpose of the group |

| • Explaining the leader’s role |

| • Explaining how the group sessions will be conducted |

| • Helping members verbalize expectations |

| • Checking out the comfort levels of the members |

| • Explaining group rules including the group contract |

| • Focusing on the content |

| • Addressing questions |

| Subsequent sessions |

| • Assessing the benefits |

| • Assessing members’ interest and commitment |

| • Assessing each member’s participation |

| • Assessing members’ level of trust and group cohesion |

| • Assessing how much to focus on the content or process |

In this analysis, we determined HIV disclosure by gender of the infected partner, age, education, occupation, and condom use. Tests of statistical significance included chi squaretest and Fisher’s exact test and analyses were done using STATA™ version 8.2.

Results

The study population comprised 293 HIV-discordant couples, among whom the male partner was HIV-infected in 192 (65.5%) and the female partner was HIV-infected in 101 couples (34.5%). Overall, 237 HIV-infected persons (80.9%) disclosed their HIV positive results and accepted facilitated couple counselling (Table 3). Disclosure was similar irrespective of the sex of the HIV infected partner (male HIV-positive couples 81.3%, female HIV-positive couples 80.2%) (Table 3). Disclosure did not differ significantly by age, education or occupation of the HIV infected partners (Table 3). Though not statistically significant, over all disclosure was higher among couples where the HIV-infected partner reported prior discussion of condom compared to no condom discussion (83.7% versus 76.5%, p=0.13). With regard to use of condoms, over all disclosure was significantly higher where the HIV-infected partner reported use of condoms compared to non condom use (87.2% versus 76.8%, p=0.03). Disclosure was also marginally significantly higher among couples in which the male partner was HIV-positive and reported having discussed use of condoms, compared to couples where the male partner was HIV infected but reported no condom discussion (85.3% versus 75.0%, p =0.07). Similarly, disclosure rates were significantly higher in couples in which the male partner was HIV-positive and reported prior use of condoms (90.1% disclosed) compared to couples who reported no prior use of condoms (75.3%, p = 0.01)(Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the HIV infected persons among discordant couples

| Characteristics | All Couples Combined | M+F− | M−F+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosed (%) | P | Disclosed (%) | P | Disclosed (%) | P | |

| Over all | 237/293 (80.9) | 156/192 (81.3) | 81/101 (80.2) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| 15–34 | 145/184 (78.8) | 478/99 (78.8) | 67/85 (78.8) | |||

| 35–49 | 92/109 (84.4) | 0.24 | 78/93 (83.9) | 0.37 | 14/16 (87.8) | 0.42 |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary or Lower | 196/240 (81.7) | 128/157 (81.5) | 68/83 (81.9) | |||

| Post primary | 41/53 (77.4) | 0.47 | 28/35 (80.0) | 0.83 | 12/18 (72.2) | 0.15 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Agriculture | 140/177 (80.9) | 86/106 (81.1) | 54/71 (76.1) | |||

| Skilled/Other | 96/116 (82.8) | 0.44 | 70/86 (81.4) | 0.96 | 26/30 (86.7) | 0.23 |

| Ever discussed Condom with this Partner? (N=293) | ||||||

| Yes | 149/178 (83.7) | 99/116 (85.3) | 50/62 (80.6) | |||

| No | 88/115 (76.5) | 0.13 | 57/76 (75.0) | 0.07 | 31/39 (79.5) | 0.89 |

| Ever Used Condom with this Partner? (N=263) | ||||||

| Yes | 109/125 (87.2) | 73/81 (90.1) | 36/44 (81.8) | |||

| No | 106/138 (76.8) | 0.03 | 67/89 (75.3) | 0.01 | 39/49 (79.6) | 0.79 |

Discussion

We found that our (facilitated couple counselling) approach to disclosure among HIV-discordant couples resulted in high rates (80.9%), irrespective of the sex of the HIV-infected partner (81.3% in male HIV-positive versus 80.2% in female HIV-positive discordant couples) (Table 3). Prior studies reported lower average HIV-disclosure rates of 49% in sub-Saharan Africa (World Health Organization, 2003) and these studies were based on self-reported disclosure by the HIV-positive partners which are subject to social desirability bias. In this study, disclosure was directly observed by the counsellor and thus, reducing on instances of social desirability biases. Also, prior studies suggested lower disclosure rates among HIV-infected women than men (Maman, S. et al, 2001; Maman, S. et al 2003; Mayfield, A., et al, 2008; Semrau, K., et al, 2005), contrary to our findings in which disclosure did not differ by gender of the HIV-infected partner. This possibly might be due to the fact that our disclosure intervention was a stepwise process involving prior sensitization couple meetings in which we registered a high degree of attendance of 100% being represented by at least one partner in addition to emphasizing the importance of disclosure and couple counselling in these sensitization meetings. Also, the availability of free HIV care and antiretroviral therapy offered by the Rakai Health Sciences Programme could have enhanced the disclosure proportions.

Disclosure was also marginally significantly higher among couples in which the male partner was the HIV-infected and reported prior discussion of condoms and significantly higher where the male partner was the HIV-infected and reported use of condoms. These results are similar to findings from previous studies (Allen S. et al, 1992; Crepaz, N., &Marks, G., 2003; Semrau, K., et al, 2005) suggesting that interpersonal communication on safe sex may facilitate disclosure. Also, it is possible that gender-associated power imbalances within couple relationships may contribute to greater rates of disclosure where male partners are the HIV sero-positive compared to where female partners are the HIV infected.

It is difficult to generalize our findings to the usual VCT programmatic settings in which most clients coming for couples counselling are self-selected because they have already agreed to disclosure prior to attending the service. It is possible that because individuals in this study were research participants, they may be more motivated to disclose their HIV test results. However, the stepwise process of sensitization meetings, agreement by the infected partner and subsequent disclosure may be applicable to HIV longitudinal studies where married or cohabiting respondents are enrolled as individuals, in national HIV sero-surveys and in the roll-out of male circumcision for HIV prevention programmes where married or cohabiting individuals are part of the target group.

In summary, we found that high rates of disclosure of HIV results among HIV-discordant couples can be achieved using a phased approach of sensitization meetings, individual-level counselling to gain agreement from the HIV-infected partner and ultimately open disclosure of results by the couple.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (#U1AI51171), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (#22006.02) and the Fogarty International Centre (#5D43TW001508 and #D43TW00015). This study was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

The authors would like to thank the study participants whose commitment and cooperation to disclosure made this study a success. We also thank the field counsellors for their continuous endurance and effort in locating, counselling and mobilizing these couples without whom this study would have not proceeded. Finally we thank Rakai Health Sciences Programme management for all the support in developing this paper.

References

- Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. British Medical Journal. 1992;304(6842):1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell R, Opio A, Musinguzi J, Kirungi W, Ekwaru P, Mishra V, et al. HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-infected adults in Uganda: Results of a nationally representative survey. AIDS. 2008;22(5):617–624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Ruberantwari A, Malamba S, Whitworth JA. Rates of HIV-1 transmission within marriage in rural Uganda in relation to the HIV sero-status of the partners. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1083–1089. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marks G. Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care. 2003;15:379–387. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Walque D. Discordant couples: HIV infection among couples in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania. Washington, D.C: Development Research Group, the World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Male Circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: Cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14(15):2371–2381. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357:1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BL, De Bruyn G, Farquhar C. HIV-1-Discordant Couples in Sub-Saharan Africa: Explanations and Implications for High Rates of Discordance. Current HIV Research. 2007;5(4):416–429. doi: 10.2174/157016207781023992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hira SK, Feldblum PJ, Kamanga J, Mukelabai G, Weir SS, Weir JC. Condom and Nonoxynol-9 use and the incidence of HIV infection in serodiscordant couples in Zambia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1997;8(4):243–250. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugonnet S, Mosha F, Todd J, Mugeye K, Klokke A, Ndeki L, et al. Incidence of HIV Infection in Stable Sexual Partnerships: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 1802 Couples in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome and Human Retro virology. 2002;30:73–80. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett GP, Sweat MD, et al. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17:2245–2252. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Sweat M. Women’s barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care. 2001;13(5):595–603. doi: 10.1080/09540120120063223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Hogan N, Kilonzo GP, Weiss E, Sweat M. High Rates and Positive Outcomes of HIV-Serostatus Disclosure to Sexual Partners: Reasons for Cautious Optimism from a Voluntary Counseling and Testing Clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS and Behaviour. 2003;7(4):373–382. doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000004729.89102.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield A, Rice E, Flannery D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. HIV disclosure among adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):80–92. doi: 10.1080/09540120701449138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna SL, Muyinda GK, Roth D, Mwali M, Ng’Andu N, Myrick A, et al. Rapid HIV testing and counselling for voluntary testing centres in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(4):299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton DS, Galletly LC. Reducing HIV Transmission Risk by increasing Serostatus Disclosure: A Mathematical Modelling Analysis. AIDS and Behaviour. 2007;11(5):698–705. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9187-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Chuanjun L, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Viral Load and Heterosexual Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. New England Journal of medicine. 2000;342:921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semrau K, Louise K, Vwalika CV, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, Chipepo K, et al. Women in couples antenatal HIV counselling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS. 2005;19(6):603–609. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163937.07026.a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkoro PK, Boerma JT, Klokke HA, Ng’weshemi JL, Muro SA, Gabone R, et al. HIV Incidence and HIV-Associated Mortality in a Cohort of Factory Workers and Their Spouses in Tanzania, 1991 through 1996. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;23(2):194–202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200002010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwadda D, Gray HR, Wawer MJ, Stallings YR, Sewankambo NK, Konde-Lule J, et al. The social dynamics of HIV transmission as reflected through discordant couples in rural Uganda. AIDS. 1995;9:745–750. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MK. Male Self-Disclosure of HIV-Positive Serostatus to Sex Partners: A review of the Literature. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS care. 2005;16(6):33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania Government and ORC Macro. Tanzania HIV/AIDS Indicator Survey 2003–04: Tanzania Commission for AIDS and National Bureau of Statistics. Dares Salam; Tanzania: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Opening up the HIV/AIDS epidemic: Guidance on encouraging beneficial disclosure, ethical partner counselling and appropriate use of HIV case-reporting. Geneva: Switzerland; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. A review paper. Geneva: Switzerland; 2003. Gender dimensions of HIV status disclosure to sexual partners: Rates, barriers and outcomes. [Google Scholar]