Abstract

This study observed young, middle-aged and older adults (N = 239; Mage = 49.6 years, range = 18-89 years) for 30 consecutive days to examine the association between daily stress and negative affect taking into account potential risk (i.e., self-concept incoherence) and resilience factors (i.e., age, perceived personal control). Results indicated that younger individuals and individuals with a more incoherent self-concept showed higher average negative affect across the study. As well, individuals reported higher negative affect on days that they experienced more stress than usual and on days that they reported less control than usual. These main effects were qualified by significant interactions. In particular, the association between daily stress and negative affect was stronger on days on which adults reported low control compared to days on which they reported high control (i.e., perceptions of control buffered stress). Reactivity to daily stress did not differ for individuals of different ages or for individuals with different levels of self-concept incoherence. Although all individuals reported higher negative affect on days on which they reported less control than usual, this association was more pronounced among younger adults. This study helps to elucidate the role of risk and resilience factors when adults are faced with daily stress.

Keywords: adulthood, self-concept incoherence, perceived control, daily stress, daily negative affect

Risk and Resilience Factors in Coping with Daily Stress in Adulthood: The Role of Age, Self-Concept Incoherence, and Personal Control

Theoretical models of coping with daily stress have increasingly emphasized that individuals bring both risk and resilience factors to the stressful events and situations in their lives (Almeida, 2005; Lazarus, 1999; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Zautra, 2003). Understanding how different risk and resilience factors influence coping processes in daily life is essential to explaining the great interindividual variability in individuals’ responses to stressful events (Lazarus) and to explaining developmental processes in adulthood (Aldwin, 2007). The present study focused on individuals’ age, self-concept incoherence, and perceptions of personal control as potential risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress. Previous studies have often examined adults’ responses to daily stress over rather short periods of time (e.g., one week) or only in extreme age groups (young vs. older adults), thus, warranting further examination of the role of age as a potential risk or resilience factor in coping with daily stress over longer periods of time. Similarly, previous studies rarely have examined the effects of multiple risk and resilience factors simultaneously. The present study extends earlier work by including a more complete age span of adulthood and by simultaneously examining the influence of multiple risk and resilience factors on adults’ responses to daily stress over a 30-day period.

Age and Coping with Daily Stress

Examining the role of age in the context of daily stress is important for several reasons. First, although there is increasing consensus that the rate of exposure to daily stressors tends to decline with age (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Stawski, Sliwinski, Almeida, & Smyth, 2008; Zautra, Finch, Reich, & Guarnaccia, 1991), findings regarding the role of age in terms of reactivity to daily stress have been mixed. On one hand, Mroczek and Almeida (2004) found a stronger association between daily stress and negative affect for older adults compared to younger adults, suggesting that older adults may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of daily stress. On the other hand, Uchino, Berg, Smith, Pearce, and Skinner (2006) reported that older individuals showed less of an increase in negative affect during daily stress compared to their younger counterparts. Finally, in contrast to both Mroczek and Almeida and Uchino et al., Stawski et al. reported that emotional reactivity to daily stressors did not differ between younger and older adults.

What makes it difficult to compare the findings from these studies is that they examined adults of different age ranges over different, and possibly not sufficiently long enough, time spans. For example, although participants in Mroczek and Almeida's (2004) study came from a nationally representative sample ranging in age from 25 to 74 years, their sample did not include very old individuals. Similarly, Uchino et al.'s (2006) sample did not include young adults or very old adults (age range 36 to 75 years) and adults in the oldest age bracket represented only a small percentage of the total sample. Thus, findings from these two studies are limited in terms of estimating the effect of age on coping with daily stress because they fail to adequately represent adults in the very old age range. Inclusion of very old adults, however, is important because individuals in this age range may show less reactivity to stress than younger individuals due to lowered physiological reactivity (Levenson, 2000). Furthermore, whereas Stawski et al. (2008) studied young and older adults, including very old adults, their sample did not include middle-aged adults. Findings from this study, therefore, are of limited utility for estimating the effect of age because of the omission of middle-aged adults, an age group with relatively high levels of stress exposure (Almeida & Horn, 2004).

The present study permits a more complete examination of chronological age as a potential risk or resilience factor because it included young, middle-aged and older adults (including very old individuals) at equal rates and observed participants over a 30-day period. The 30-day period is relevant, because it provides a large enough window to assess individuals’ daily stress comprehensively (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003; Scollon, Kim-Prieto, & Diener, 2003). In addition, a 30-day period may capture a broader range of daily stressors normally encountered by adults than shorter observation periods because research has shown that, on average, adults report stressful events for about 50% of the days in a given study (Almeida, Whethington, & Kessler, 2002; Bolger et al.; Reis & Gable, 2000). Thus, the present study complements earlier studies with relatively short observation periods (i.e., Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Stawski et al., 2008; Uchino et al., 2006) by examining daily stress reports over a longer period of time.

Second, when examining the effect of age on reactivity to daily stress it is also important to examine whether age in general is associated with the degree of variability in an observed outcome such as negative affect. Specifically, it is crucial to examine whether age is in any systematic way related to variability in negative affect regardless of the level of daily stress. Both data from cross-sectional (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) and longitudinal studies (Charles, Reynolds, & Gatz, 2001; Griffin, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2006) suggest that the average level of negative affect tends to decrease with age. Similarly, data from an experience sampling study showed that older adults tended to rebound from negative emotional experiences quicker than younger individuals (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000). Taken together, these findings suggest that both adults’ average levels of negative affect and their overall variability in negative affect may decrease with age. Consequently, when examining reactivity to stress, it is important to consider such reactivity within the context of any age differences in average levels of negative affect as well as overall variability in negative affect (see also Chow, Hamagami, & Nesselroade, 2007).

Third, examining the association between chronological age and reactivity to daily stress may provide an avenue for better understanding the age-related nature of certain diseases (Uchino et al., 2006), such as cardiovascular disease or cancer. In particular, if increasing age is associated with greater vulnerability to the effects of acute and chronic stress, then this would warrant further systematic investigation of the pathways and mechanisms by which age compromises individuals’ health and well-being (Almeida, 2005). Such research may also result in the identification and development of psychosocial interventions with a focus on teaching individuals how to cope more effectively with acute and chronic stress.

In summary, given the findings from previous studies and given the evidence from research on age differences (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) and age changes in positive and negative affect (Charles et al., 2001; Griffin et al., 2006) and coping strategies (Diehl, Coyle, & Labouvie-Vief, 1996), we hypothesized that compared to younger adults, older adults would (a) have lower levels of average daily negative affect and (b) exhibit less day-to-day variability in negative affect. Furthermore, based on the available findings on the role of age in stress reactivity, we hypothesized that age would not moderate the effect of daily stress on negative affect. That is, we hypothesized that age would not be associated with greater reactivity to daily stress.

Self-Concept Incoherence as a Risk Factor

Although most studies have focused on neuroticism as a personality-related risk factor in coping with daily stress (Bolger & Schilling, 1991; David & Suls, 1999; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Suls & Martin, 2005), the present study focused on self-concept incoherence (SCI) as the risk factor of choice. SCI was operationalized in terms of self-concept differentiation (SCD). SCD assesses the extent to which a person's self-representations1 differ across different social roles and situations (Block, 1961; Donahue, Robins, Roberts, & John, 1993) and has been one of the major approaches to assessing the extent to which a person has an incoherent self-concept (Diehl & Hay, 2007; Donahue et al.).

We focused on SCI, as operationalized by an index of SCD, for several reasons. First, consistent with the notion that a person's self-concept is a cognitive structure with important self-regulatory functions (Baumeister, 1998; Higgins, 1996; Markus & Wurf, 1987), it has been shown that self-representations come into play when a person is confronted with life stress (Showers, Abramson, & Hogan, 1998). However, self-representations may fulfill their self-regulatory functions optimally only if they are coherently and integratively organized. For example, research has shown that self-structures in which self-representations are grouped exclusively into positive or negative groupings (i.e., compartmentalized self-structures) tend to be maladaptive, whereas self-structures in which positive and negative self-attributes are grouped together (i.e., integrated self-structures) tend to be associated with greater stability, increased resilience, and more adaptive ways of coping with stress (Showers et al.; Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007).

Second, cross-sectional research has shown that SCD is indicative of SCI and self-fragmentation and higher levels of SCI tend to be associated with poorer psychological outcomes, such as higher levels of anxiety and depression, and lower levels of self-esteem and psychological well-being (Diehl, Hastings, & Stanton, 2001; Donahue et al., 1993). To date, research has not focused on the association between SCI and day-to-day indicators of well-being. Nonetheless, existing findings suggest that SCI would be positively associated with adults’ mean level of daily negative affect.

Third, examining SCI may shed light on mixed findings regarding age differences in negative affect and stress reactivity. Notably, Diehl et al. (2001) showed that the association between SCI and psychological well-being (PWB) was moderated by participants’ age. In particular, for older adults a high level of SCI was associated with significantly lower levels of positive PWB and significantly higher levels of negative PWB compared to younger adults. This finding suggests that a coherent sense of self (i.e., low SCI) may be of particular importance in later life when negative age-related changes challenge a person's self-concept (Freund & Smith, 1999; Troll & Skaff, 1997). Such challenges to a person's self-concept often occur in the context of daily stress.

Fourth, previous work has provided a rather decontextualized view of SCI and has focused on fairly general associations with measures of adjustment and PWB. In contrast, the present study examined whether and to what extent SCI was associated with individuals’ intraindividual variability in daily affect as well as their reactivity to daily stress. Thus, although SCI may be a relatively stable personality characteristic, we examined its effects in the context of daily events. Specifically, we hypothesized that greater SCI makes it more difficult for an individual to respond to daily events in a coordinated and planful fashion, resulting in greater perturbation of the established person-environment fit. With respect to daily stress, we expect this greater perturbation of the person-environment fit to be observable as increased reactivity to daily stress. Thus, we hypothesized that a person with a high SCI score would respond to daily stress events with a more pronounced increase in negative affect than a person with a low SCI score. This increased reactivity to stress may underlie the negative associations between indices of SCI and indicators of physical and psychological well-being documented in cross-sectional studies and may, over time, put the individual at greater risk for experiencing poorer physical and psychological health.

In summary, we hypothesized that greater SCI would be associated with (a) higher mean levels of daily negative affect, (b) greater intraindividual variability in negative affect, and (c) greater increases in negative affect in response to daily stress (i.e., increased stress reactivity). In addition, we hypothesized that the association between SCI and reactivity to stress would be moderated by age. Specifically, based on the cross-sectional findings reported by Diehl et al. (2001), we expected that the association between SCI and reactivity to stress would be significantly stronger in older adults compared to younger adults. That is, we anticipated that older adults would be more vulnerable to the negative effects of high SCI such that having highly incoherent self-concept would be more strongly associated with stress reactivity among older versus younger adults.

Personal Control as a Resilience Factor

Besides examining the role of SCI as a personality-related risk factor in coping with stress, the present study also focused on adults’ daily beliefs of personal control as a resilience factor. Although there is an extensive body of work showing that personal control beliefs play an important role with regard to adjustment and well-being (Bandura, 1997; Lachman & Firth, 2004; Skinner, 1995), research on the effects of control beliefs in the context of daily stress has been fairly limited. Moreover, the role of control beliefs has rarely been studied vis-à-vis existing risk factors, such as SCI. Thus, the present study examined the effect of daily control beliefs simultaneously with an identified personality-related risk factor.

A large body of research has shown that perceptions of personal control are associated with a variety of positive outcomes, such as better physical and mental health, psychological well-being, and lower mortality (Bandura, 1997; Eizenman, Nesselroade, Featherman, & Rowe, 1997; Skinner, 1995). Greater personal control has also been shown to be associated with lower reactivity to stressors in daily life (Hahn, 2000; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007; Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2005). For example, Neupert et al. reported findings from the National Study of Daily Experiences showing that lower levels of perceived control measured at one point in time were related to greater emotional and physical reactivity to stressors in the interpersonal and work domain, and to greater emotional reactivity to network stressors. These authors also showed that the effects of personal control differed by age group. Moreover, Ong et al. showed in a daily diary study with bereaved women that the stress-anxiety association was significantly reduced on days of greater perceived control. Taken together, findings from these studies suggest that beliefs of personal control do not only matter as an individual difference variable (i.e., between-person characteristic) but that they also play an important role as a within-person characteristic when individuals cope with daily stress (see also Eizenman et al.).

Based on the findings from these previous studies, we hypothesized that perceived daily control would be associated directly with daily affect and would also buffer the impact of stress on negative affect. In addition, we hypothesized that the buffering effect of perceived control on reactivity to stress would differ by age and by level of SCI. Specifically, consistent with the findings reported by Neupert et al. (2007), we hypothesized that the buffering effect of perceived control on the stress-affect association would be significantly stronger in younger adults compared to middle-aged and older adults. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the buffering effect of perceived control on the stress-affect association would be significantly stronger for individuals with lower SCI compared to individuals with greater SCI (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007). This hypothesis reflects the assumption that beliefs of personal control have a greater beneficial effect for individuals with a coherent self-concept compared to individuals with an incoherent self-concept. In addition, this hypothesis is also consistent with the observation that individuals with a more incoherent self-concept tend to report lower levels of perceived personal control in general.

The Present Study

The present study had three objectives. The first objective addressed intraindividual variability in daily affect and considered whether such variability varied as a function of age and SCI. Specifically, we hypothesized that older adults would show less variability in daily affect than younger adults and that SCI would be positively associated with variability in daily affect.

The second objective focused on the association between daily stress and daily negative affect (i.e., stress reactivity) and examined the effects of personality-related risk and resilience factors, namely SCI and perceived control, on stress reactivity. We examined four specific hypotheses. First, we expected that daily stress would be positively associated with daily negative affect. Second, we anticipated that individuals with high SCI scores would respond to daily stress events with a more pronounced increase in negative affect than individuals with low SCI scores. Third, we expected that perceived daily control would buffer the impact of stress on negative affect. Fourth, we anticipated that the buffering effect of perceived daily control on stress reactivity would depend upon adults’ SCI scores. Specifically, we hypothesized that the ability of perceived control to buffer stress reactivity would be strongest among adults with low SCI scores.

The third and final objective examined the effect of age on stress reactivity and addressed whether age moderated the role of the personality-related risk and resilience factors (i.e., SCI and perceived control, respectively) on stress reactivity. We examined three specific hypotheses. First, we examined the hypothesis that age would not be associated with greater reactivity to daily stress. Second, we examined whether age moderated the association between SCI and reactivity to stress. Specifically, we expected that the association between SCI and reactivity to daily stress would be stronger among older adults versus younger adults. Third, we examined the hypothesis that the buffering effect of perceived daily control on reactivity to stress would be significantly stronger in younger adults compared to middle-aged and older adults.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 120 men and 119 women. Participants were recruited from a tri-county area in North Central Florida (i.e., Alachua, Columbia, and Marion county) using a mix of sampling procedures. Specifically, 25% of participants were recruited through random digit dialing, 25% through letters of invitation to University of Florida alumni, 45% through convenience methods (e.g., flyers, newspaper ads) and 5% through a retirement community. Because the study focused on the effects of daily stress in healthy community-residing adults, participants could not have any major sensory impairments, concurrent depression, or history of severe mental illness. Participants also had to be physically able to come to the testing location, and have adequate cognitive ability to complete the study protocol. These eligibility criteria were established during a screening interview.

To ensure an even distribution of age, participants were recruited from three age groups: young adults (n = 81; age range 18-39 years), middle-aged adults (n = 81; age range 40-59 years), and older adults (n = 77; age 60 and older). Thus, the overall sample ranged in age from 18 – 89 (M = 49.6 years, SD = 19.6 years); Table 1 presents the mean ages within age groups. To achieve a balanced distribution of gender, we oversampled middle-aged and older men using letters of invitation and flyers. Gender was evenly distributed within each age group.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Percentage of Days with Different Stressor Types by Age Group

| Young adults (n = 81) | Middle-aged adults (n = 81) | Older adults (n = 77) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | |||

| Age | 26.1 (5.9) | 52.4 (4.7) | 71.4 (4.8) |

| Self-concept incoherence (SCI) | .19a (.10) | .16a,b (.10) | .14b (.11) |

| Education (in years) | 16.1a (2..6) | 16.5a (3.1) | 16.3a (3.2) |

| Life satisfaction1 | 4.6a (.74) | 4.5a (.78) | 4.8a (.62) |

| Health2 | 5.2a (.76) | 5.2a (.86) | 5.2a (.89) |

| Mean daily stress3 | .75a (.41) | .76a (.42) | .71a (.59) |

| Mean daily control3 | 17.7a (2.6) | 18.2a,b (2.8) | 19.1b (2.1) |

| Mean daily negative affect3 | 14.0a (2.9) | 12.6b (2.4) | 11.9b (2.4) |

| Mean Percent of Days Characterized by Stressor Types | |||

| Argument/disagreement | 9.2a | 8.7a | 8.7a |

| Avoided argument/disagreement | 10.1a | 12.4a | 9.9a |

| Work/school/volunteer stress | 19.0a | 15.5a | 9.0b |

| Home stress | 14.3a | 14.7a | 14.7a |

| Health stress | 7.3a | 7.7a | 11.6b |

| Network stress | 6.3a | 7.3a | 7.7a |

| Other stress | 8.7a | 9.7a | 9.7a |

Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

Participants rated their life satisfaction on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = extremely unhappy to 6 = extremely happy.

Subjective health was rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = very poor to 6 = very good.

Mean values reflect averages across within-person study days. Means in the same row that do not share subscripts differ at p < .05 in the Tukey honestly significant difference comparison.

Most of the participants identified themselves as Caucasian (88%), 9% as Black, and 3% as Hispanic. All participants spoke English as their primary language. On average participants reported 16.3 years of education (SD = 2.9 years, see Table 1) and 62% had a college degree or higher. The median reported annual income was $35,000-50,000. Most of the young adults (72.8%) were single, whereas most middle-aged (65.4%) and older adults (62.3%) were married. The young adults were approximately evenly divided between those who were employed (full- or part-time) and those who were students, whereas the majority of the middle-aged adults were employed and the majority of the older adults were retired. Additional information is presented in Table 1. Participants described themselves as being in good health (1 = very poor, 6 = very good) and being satisfied (1 = extremely unhappy; 6 = extremely happy) with their lives (see Table 1).

Procedure

Participants first attended a 2 to 3 hour individual baseline session. Most participants completed the session at the Adult Development and Aging laboratory on the campus of the University of Florida. A subset of older adults (n = 16) completed their testing at the retirement community in which they resided. The day following the baseline session, participants began 30 consecutive daily assessments, consisting of an evening phone interview and a diary. Both, baseline sessions and daily phone interviews were conducted by trained research assistants. The daily diaries were self-administered. Participants completed diaries each evening at approximately the same time.

Participants were instructed to mail the diaries in pre-paid envelopes the day following completion. Through close monitoring during data collection, including monitoring the time elapsed from diary completion to receipt of diaries, checking postal date stamps, cross-checking information provided in the diaries with information obtained during daily interviews, and following up with all participants who did not return their diaries in a regular and timely manner, we determined that participants who failed to complete the majority of their dairies often failed to follow the study protocol when they filled out diaries (e.g., completing their diaries late and/or completing multiple diaries on the same day). Thus, to ensure that the sample consisted of participants who followed the prescribed study protocol and provided daily data in the correct manner, we required that participants complete a minimum of 24 interviews and 24 diaries (80%) in the 30-day period to be included in the final sample. As a result, 43 participants were excluded from analyses due to insufficient daily data. In addition, one participant was excluded because of missing data on a key measure used in this study. The final sample included 239 participants.

Participants who were excluded were compared to those in the final sample on a number of baseline measures. In comparison to the final sample, participants who did not complete the study protocol were younger, F(1, 282) = 8.06, and rated themselves in poorer health, F(1, 282) = 8.12, both p's < .01. They also exhibited scores indicative of poorer psychological well-being (PWB) on a number of measures assessing positive and negative dimensions of PWB, including the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), F(1, 282) = 13.60, p < .001, the negative affect subscale of the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clarke, & Tellegen, 1988), F(1, 282) = 11.00, p < .001, and the Self-Acceptance and Purpose in Life subscales of the Scales of Psychological Well-being (Ryff, 1989), F(1, 282) = 5.10 and F(1, 282) = 4.10, both p's < .05, respectively. Participants who were excluded, however, did not differ from those in the final sample on the average number of stressors they experienced per day.

The 239 participants were in the study for a total of 7,170 days (30 days each). Given our analytic strategy (see below) only days with complete data on all measures of interest were included in the analyses. Thus, the presented analyses are based on 6,715 days of data (an average of 28.1 days of data per person, SD = 2.1 days, range 24 to 30 days).

Measures

Measures administered during the baseline session assessed a variety of sociodemographic and personal information, including participants’ self-concept incoherence and select personality traits. Daily phone interviews assessed positive and stressful events participants experienced that day. Measures included in the daily diaries assessed physical, emotional, and cognitive states participants experienced on a day-to-day basis.

Self-Concept Incoherence (SCI)

Following the approach first introduced by Block (1961), participants rated how characteristic 40 self-attributes (e.g., selfish, considerate) were of (a) their true self and themselves with their (b) family, (c) spouse or significant other, (d) a close friend, and (e) a colleague (1 = extremely uncharacteristic, 8 = extremely characteristic). Participants who did not currently have a significant other or colleague were instructed to think of what they were like in those relationships in the past. Each participant's set of ratings were correlated and the resulting 5 × 5 correlation matrix was subjected to a within-person principal components analysis (i.e., the correlation and principal components analyses were done for each person separately). The first principal component extracted represents the variance shared by the 5 self-representations and the SCD index is calculated by subtracting that shared variance from 1.00; that is, the SCD index represents the proportion of variance that is not shared by the 5 self-representations. Consequently, a person who sees him- or herself very differently across the 5 self-representations will have a high SCD score, indicating high SCI. In contrast, a person who sees him- or herself very similarly across the 5 self-representations will have a low SCD score, indicating low SCI. The reliability and criterion validity of this index has been established in a number of studies (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993; Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, 1997).2

Daily Stress

Each day during their phone interviews, participants completed the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida et al., 2002). The DISE is a semi-structured interview that was developed on a nationally representative sample of adults ranging in age from 25 to 74 years. The DISE consists of 7 stem questions assessing the occurrence of stressors, including having or avoiding arguments, as well as stressors that occur in various domains of life (e.g., at work/school/volunteering, in personal health). The number of stressful events participants experienced each day was summed to create an index of daily stress. Scores can range from 0 to 7, with higher scores indicating more stressors. Participants reported experiencing no stressors on 45% of the days and 1 or more stressors on 55% of the days. The median number of stressors experienced per day was 1; the mean number of stressors experienced per day was .75 (SD = .82 stressors; range = 0-6 stressors). Participants also rated the severity of each daily stressor on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all stressful; 4 = very stressful). The correlation between the number of stressors participants reported each day and the summed severity of those stressors was high (r = .94, p < .05), indicating high collinearity. Given that these two variables capture similar information, and to be consistent with other studies that focused on the occurrence of daily stressors (e.g., Bolger & Schilling, 1991; Stawski et al., 2008), we used the number of stressors participants’ reported each day in all analyses.

Daily Perceptions of Personal Control

Participants’ daily perceptions of personal control were assessed using the locus of control (LOC) subscale from Eizenman et al.'s (1997) perceived control scale. Items were modified to assess participants’ perceptions of personal control for the past 24 hours (e.g., “In the past 24 hours, I have felt I am being pushed around in my life”—reverse coded). Participants indicated how much they agreed with 4 items on a 6-point scale (1 = disagree strongly; 6 = agree strongly). Higher scores indicated that participants’ perceived greater control. We estimated the internal consistency coefficient on the 5th day of assessment and every 10 days thereafter (see Eizenman et al.). The resulting coefficients for the 5th, 15th, and 25th day of assessment were .62, .75, and .73, respectively.

Daily Negative Affect

Each day, participants completed the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). The negative affect scale consists of 10 items that assess a general dimension of aversive affective states such as feeling angry, fearful, nervous, and distressed. Respondents indicated how often they had felt this way during the past 24 hours on a 5-point scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 5 = extremely). Thus, daily affect scores can range from 10 to 50, with higher scores being indicative of a higher level of negative affect. The PANAS has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Watson et al.). Again, we estimated the internal consistency coefficients on the 5th, 15th, and 25th day of measurement. The resulting coefficients were .84, .83, and .85, respectively.

Preliminary Data Manipulation

The analyses focused on examining the associations between participants’ daily negative affect and within-person variables (e.g., daily stress; daily perceptions of control) and between-person variables (e.g., age and SCI). Prior to estimating models, we centered all within-person independent variables on the person's own mean. Using stress as an example, the resulting daily stress score was (a) 0 on a day when an individual experienced his or her average level of stress, (b) greater than 0 on a day when a person experienced more than his or her average level of stress, and (c) less than 0 on a day when an individual experienced less than his or her average level of stress. Centering each participant's daily scores on his or her individual mean ensures that the within-person scores reflect primarily within-person variance (Ong & Allaire, 2005).

In addition, all between-person independent variables (e.g., age and SCI) were deviated around the sample mean. Consequently, the resulting parameters indicate the average intercept and the average association between the independent and dependent variables (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Statistical Analyses

All hypotheses were tested using multilevel modeling (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Multilevel models allowed us to (a) consider whether the magnitude of individuals’ variability in daily negative affect was affected by their age and level of SCI and (b) simultaneously model the effect of within- and between-person variables on daily negative affect.

We modeled associations between daily negative affect and the within-person predictors (i.e., daily stress and daily control) at level 1. The within-person model was:

| (1) |

In Equation 1, β0j is a person's level of negative affect on a day when he/she experiences his/her average level of stress and perceived control, β1j is the association between daily stress and negative affect for person j and indicates his/her reactivity to stress. Analogously, β2j is the association between control and negative affect for person j and indicates his/her sensitivity to control. Finally, β3j is the interaction of stress and control for person j and reflects whether his/her perceptions of control buffer his/her reactivity to stress. The last element in the equation (eij) represents a random residual component or error.

The level 2 equations model the associations between daily negative affect and the between-person predictors (i.e., age and SCI) as well as the role of the between-person variables as moderators of the level-1 associations (e.g., testing whether age moderates the association between stress and negative affect). Given that testing some of the hypothesized moderation effects requires 3-way interactions, all possible 2-way interactions were included. The level 2 equations were:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Equation 2 for β0j describes individuals’ levels of negative affect (i.e., their individual intercepts), equation 3 for β1j describes adults’ reactivity to stress (i.e., the association between adults’ daily stress and negative affect), equation 4 for β2j describes adults’ sensitivity to control (i.e., the association between adults’ daily control and negative affect), and equation 5 for β3j tests the buffering role of daily control on adults’ reactivity to stress. Solving and rearranging the within- and between-person equations simultaneously as described in Raudenbush & Bryk (2002) yields the complete model and more clearly demonstrates how the model tests all our hypotheses:

| (6) |

Specifically, the term γ00 represents the grand mean for negative affect. Focusing on the terms that test our hypothesized effects, γ10 is a test of the average effect of daily stress on negative affect (i.e., whether daily stress influences daily NA) and γ20 is a test of the average effect of daily control on negative affect (i.e., whether daily control influences daily NA). γ30 is a test of whether, on average, daily control buffers the association between daily stress and daily negative affect (i.e., whether perceptions of control buffer stress reactivity). Regarding the main effects of SCI and age, γ01 and γ02 test the effect of adults’ self-concept incoherence scores and age, respectively, on their average negative affect. γ11 and γ12 test the interaction of SCI and age, respectively, with daily stress. Thus, these effects test whether SCI and age moderate adults’ reactivity to stress. Finally, the parameters γ13, γ31 and γ31 test our hypotheses regarding the interactions of age, SCI, control, and stress reactivity. Specifically, γ13 tests whether age moderates the effect of SCI on reactivity to stress, γ31 tests whether SCI moderates the stress buffering effect of daily perceptions of control, and γ32 tests whether age moderates the stress buffering effect of daily perceptions of control. The parameters γ03 γ21 and γ22 do not test any hypothesized effects but need to be included because of the inclusion of the hypothesized higher-order effects. Finally, μ0j, μ1j, μ2j, and μ3j represent the unexplained variance in participants’ random intercepts and slopes.

We began with models that simply decomposed the variance into within- and between-person variance and examined whether intraindividual variability in daily negative affect varied as a function of age and SCI. Then we tested our hypotheses regarding fixed effects. It is important to note that the estimation of effect sizes in multilevel modeling is not straightforward and different methods of approximating effect sizes have been proposed (cf. Roberts & Monaco, 2006; Singer & Willett, 2003; Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Here we adopt the model building and pseudo-R2 approach described by Singer and Willet. This approach allowed us to estimate the percentage of within- or between-person variance that was explained by the independent variables. The estimation of such pseudo-R2 values requires that each variable be added to the model in a step-by-step process of increasing model complexity. Given space constraints, we do not provide all the details of that process here. Rather, we present (a) the results of our final model, (b) the proportion of variance in daily negative affect that was explained when significant predictors of negative affect were added to the model, and (c) the 95% confidence interval of the estimates. The Proc Mixed procedure in SAS was used to estimate the models (SAS Institute, 2000).

Results

The results section has three parts. First, we report descriptive statistics and correlations for the variables of interest. Second, we present models examining intraindividual variability in negative affect as a function of age and SCI. Third, we report the findings from the models examining the role of age, SCI, and perceived control in daily negative affect and reactivity to stress.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the between-person variables (i.e., age, SCI, mean daily stress and control) and mean daily negative affect along with details of the types of stressors reported by young, middle-aged, and older adults. As can be seen in Table 1, there were some significant differences between age groups. In particular, the average SCI score was significantly higher in young adults compared to older adults. Young adults also reported significantly lower mean daily control compared to older adults and significantly higher mean daily negative affect compared to middle-aged and older adults. There were no significant age group differences in mean daily stress. In terms of specific types of daily stressors, young and middle-aged adults reported school and work stressors on a significantly higher percent of days than older adults did. In contrast, older adults reported health stressors on a significantly higher percent of days than young and middle-aged adults did.

The intercorrelations of the variables are presented in Table 2. The percent of stressor days reported by participants (and the mean number of daily stressors) was somewhat higher than reported by Almeida et al. (2002). Nonetheless, the pattern suggested by the descriptive data and the bivariate associations was consistent with our expectations. Notably, at the between-person level the bivariate associations revealed that older adults and adults with lower SCI scores reported lower mean negative affect. At the within-person level, these aggregated associations indicate that, on average, higher levels of stress and lower levels of daily control were associated with increased negative affect. Examining associations based on aggregated data, however, does not allow a full consideration of within- and between-person associations or an examination of the variance attributable to different types of variables and, therefore, we turn our attention to multilevel models.

Table 2.

Correlations of Average Daily Negative Affect with Age, Self-Concept Incoherence, and Between-Person Mean Daily Stress and Control (N = 239)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | ||||

| 2. Self-concept incoherence (SCI) | -0.22 | – | |||

| 3. Mean daily stress | -0.04 | 0.13 | – | ||

| 4. Mean daily perceived control | 0.20 | -0.33 | -0.22 | – | |

| 5. Mean daily negative affect | -0.32 | 0.35 | 0.41 | -0.49 | – |

| Mean | 49.6 | .16 | .75 | 18.4 | 12.8 |

| Standard deviation | 19.6 | .10 | .48 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

Note. Correlations |.13| ≤ r ≤ |.17| are significant at p < .05. Correlations |.18| ≤ r ≤ |.22| are significant at p < .01, and correlations r ≥.23 are significant at p < .001.

Age, Self-Concept Incoherence, and Intraindividual Variability in Negative Affect

In our first multilevel model, we simply partitioned the variance in negative affect into between- and within-person variance; 43% of the variance in negative affect was between-person (τ00 = 6.87, z = 10.44, p < .001) and 57% was within-person (σ2 = 9.04, z = 56.91, p < .001). This unconditional means model revealed there was sufficient variability in negative affect at both the within- and between-person level to proceed with multilevel analyses.

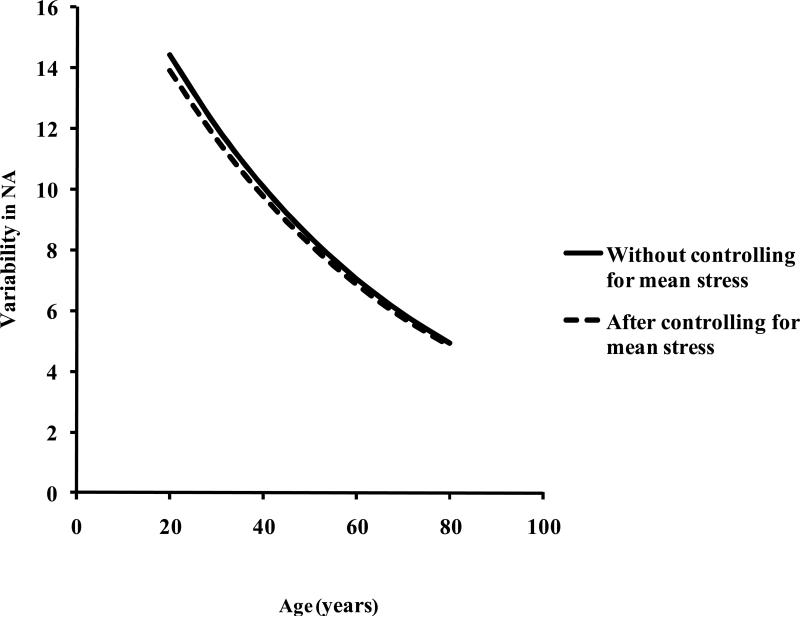

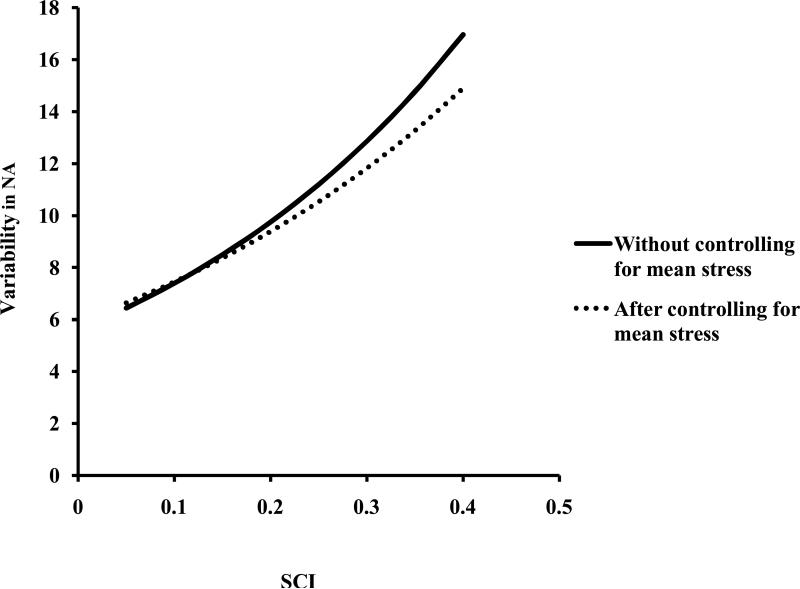

Next, we examined our hypotheses regarding age, SCI, and the degree of variability individuals experienced in daily negative affect. Specifically, we modeled intraindividual variability as a log-linear function of age and SCI (Hedeker & Mermelstein, 2007). Given that adults with higher SCI scores tended to have higher mean levels of stress (see Table 1) to ensure that any differences in intraindividual variability did not just reflect differences in mean levels of stress, we modeled intraindividual variability as a function of age and SCI before and after controlling for mean stress. As can be seen in Figure 1, these models revealed that age was negatively associated with intraindividual variability in negative affect both before and after controlling for mean stress, αage = -.02, z = -19.4, and αage = -.02, z = -19.3, both p's < .001, respectively. In contrast, SCI was positively associated with intraindividual variability in negative affect (see Figure 2). Again, the association was significant both before and after controlling for mean stress, αSCI = 2.77, z = 13.8, and αSCI = 2.31, z = 11.4, both p's < .001, respectively.

Figure 1.

Intraindividual variability in negative affect as a function of age before and after controlling for mean stress.

Figure 2.

Intraindividual variability in negative affect as a function of SCI before and after controlling for mean stress.

Self-Concept Incoherence, Control, and Age in Daily Negative Affect and Reactivity to Stress

Next, we tested our hypotheses regarding the role of age, SCI, daily stress, and daily control on daily negative affect. All effects were examined in one model (Table 3). Focusing first on the role of between person predictors and daily negative affect, it can be seen that the effects of SCI (γ01, b = 7.57, p < .05) and age (γ02, b = -.04, p < .05) were significant and in the expected direction. Specifically, individuals who had a more incoherent self-concept or were younger reported higher average negative affect. SCI accounted for 9.3% of the between-person variation in daily negative affect and age accounted for 9.9% of the between-person variation in daily negative affect.

Table 3.

Unstandardized Estimates, Standard Errors, and the 95% Confidence Intervals of Within- and Between-Person Differences in Daily Negative Affect

| Variable | Parameter | Unstandardized Estimates | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates Examining Average Level of Negative Affect | |||

| Intercept | γ 00 | 12.84 (0.16)*** | (12.52, 13.16) |

| SCI | γ 01 | 7.57 (1.54)*** | (4.53, 10.61) |

| Age | γ 02 | -0.04 (0.01)*** | (-0.05, -0.02) |

| SCI X Age | γ 03 | 0.05 (0.08) | (-0.11, -0.21) |

| Estimates Examining Reactivity to Stress | |||

| Stressij | γ 10 | 1.26 (0.07)*** | (1.11, 1.40) |

| SCI X Stressij | γ 11 | -0.04 (0.70) | (-1.41, 1.33) |

| Age X Stressij | γ 12 | 0.00 (0.00) | (-0.01, 0.00) |

| Age X SCI X Stressij | γ 13 | 0.03 (0.04) | (-.05, 0.10) |

| Estimates Examining the Within-person Influence of Control | |||

| Controlij | γ 20 | -0.41 (0.03)*** | (-0.47, -0.35) |

| SCI X Controlij | γ 21 | 0.07 (0.31) | (-0.55, 0.69) |

| Age X Controlij | γ 22 | 0.01 (0.00)** | (0.00, 0.01) |

| Estimates Examining the Buffering Role of Control on Stress | |||

| Stressij X Controlij | γ 30 | -0.09 (0.04)* | (-0.16, -0.01) |

| SCI X Stressij X Controlij | γ 31 | -0.12 (0.38) | (-0.86, 0.62) |

| Age × Stressij X Controlij | γ 32 | 0.00 (0.00) | (-0.01, 0.00) |

Note. Within-person effects of stress and control are indicated with the subscript ij.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Turning to the association between within-person predictors and daily negative affect, as expected individuals reported higher negative affect on days they experienced more stress than usual (γ10, b = 1.26, p < .05) and on days they reported less control than usual (γ20, b = -.41, p < .05). Including both the fixed and random effect of daily stress and daily control accounted for 16.6% and 16.4%, respectively, of the within-person variation in participants’ daily negative affect.

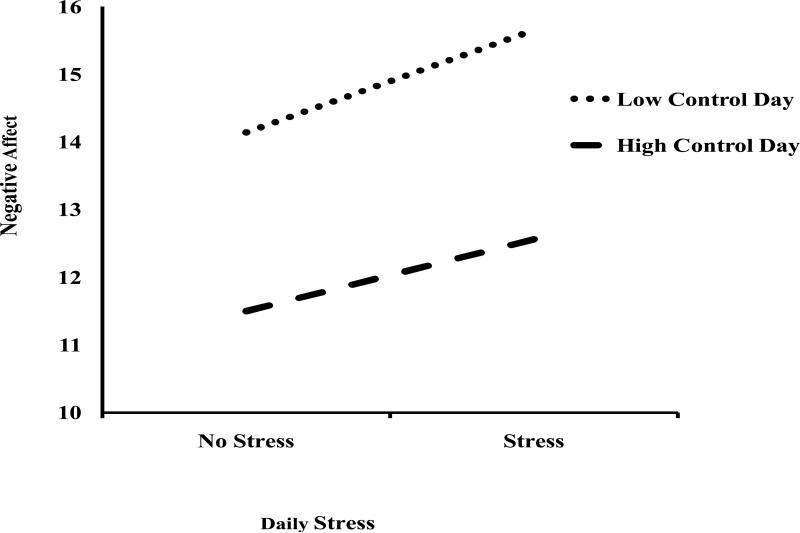

There was also a significant Daily Control × Daily Stress interaction (γ30, b = -.09, p < .05). To decompose and illustrate this interaction, we followed methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991) and Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006). Specifically, we estimated the association between daily stress and daily negative affect on days individuals reported daily control scores 1 SD above and below the mean. Figure 3 depicts this interaction on days adults reported low control (1 SD below the mean) and on days adults reported high control (1 SD above the mean). As expected, the pattern revealed that the association between daily stress and negative affect was stronger on days adults experienced low control (b = 1.5, p < .05) compared to days adults experienced high control (b = 1.1, p < .05). The inclusion of this interaction accounted for 4% of the within-person variation in adults’ daily negative affect.

Figure 3.

Daily control as a moderator of the association between daily stress and daily negative affect.

We also examined our hypotheses regarding the role of SCI and age in moderating the associations between daily stress, daily control, and negative affect. Regarding the association between daily stress and negative affect, in keeping with our expectations, age did not moderate the association between daily stress and daily negative affect (γ12, b = .00, ns). Contrary to our expectations, SCI failed to moderate the association between daily stress and daily negative affect (γ11, b = -.04, ns).

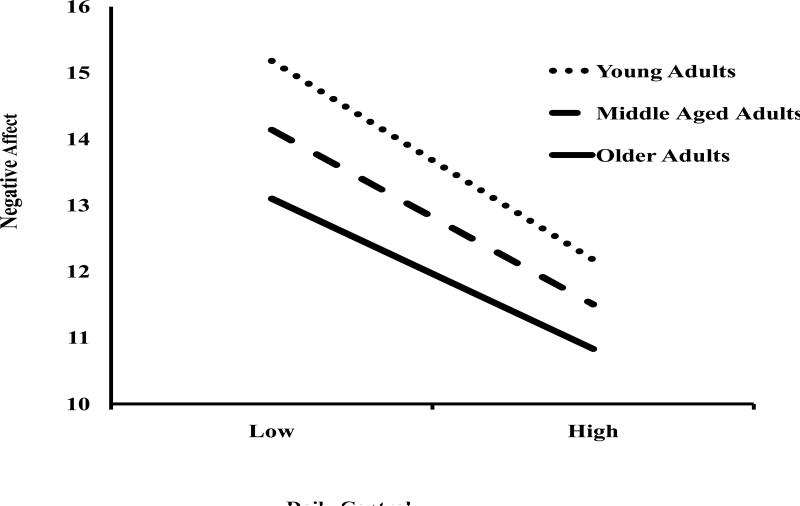

The analyses did, however, reveal that age moderated the association between daily control and negative affect (γ22, b = .01, p < .05); this interaction accounted for 5% of the variation in the within-person associations between daily control and negative affect. We decomposed this interaction for adults of mean age and adults’ 1 SD above and below the mean age on days they experienced low and high control (1 SD above and below the mean). The pattern revealed that perceptions of control and daily negative affect were more strongly associated among younger compared to older adults. Specifically, for adults 1 SD below the mean (i.e., 30 years old, roughly corresponding to young adulthood), the association between daily control and daily negative affect was b = -.53; for adults of average age (i.e., 49.6 years old, roughly corresponding to middle age), the association was b = -.47; and for adults aged 1 SD above the mean (i.e., 69.2 years of age, roughly corresponding to older adulthood) the association was b = -.40 (all slopes significant at p < .05).

Following methods outlined by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006) we determined the region of significance of this interaction; that is, the region of age over which the slope of the association between daily control and daily negative affect was significantly different from zero. This analysis revealed that the association between mean control and negative affect was significant for adults aged 89 years of age or younger. For adults older than 89 years of age the association between daily control and negative was non-significant. Although our sample did not include any adults over the age of 90, these findings suggest that the strength of the association between daily control and negative affect decreases with advancing age, and may become non-significant among the oldest-old.

Finally, we examined our hypotheses that the ability of daily perceptions of control to buffer the effect of daily stress on negative affect might vary by SCI or age (i.e., we examined the 3-way interactions between SCI × Stressij × Controlij and Age × Stressij × Controlij). Contrary to our expectations, there was no evidence that SCI or age moderated the ability of daily control to buffer daily stress (γ31 b = -.12, ns, and γ32 b = .00, ns, respectively).

Unreported analyses

Consistent with past research on daily stress, we estimated additional models controlling for gender and years of education (e.g., Neupert et al., 2007), as well as models including neuroticism as an additional covariate (e.g., Mroczek & Almeida, 2004).3 Also, given that the associations among the variables of interest could reflect the influence of linear trends, we estimated our models with and without day of study as an additional control variable (Ong & Allaire, 2005). The pattern of findings was unchanged and the reported models do not include these additional variables.

We also examined whether age had a curvilinear association with daily negative affect and stress reactivity (i.e., we tested the effect of an age2 term). There was no support for a curvilinear association of age and the inclusion of this effect did not alter the pattern of findings. These models were not reported.

Discussion

The present study addressed three objectives. The first objective examined intraindividual variability in daily affect and whether such variability varied as a function of age and SCI, and the role of mean level of stress in such associations. The second objective focused on the association between daily stress and daily negative affect and examined whether the association between stress and negative affect was moderated by personality-related risk and resilience factors. Finally, the third objective examined the effect of age on the association between daily stress and daily negative affect and whether the effects of the personality-related risk and resilience factors were moderated by age. Overall, findings supported several of the study hypotheses and contribute to the literature on the effects of daily stress in multiple ways.

Daily Stress and Negative Affect

Consistent with previous work (Bolger & Schilling, 1991; DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988; Suls & Martin, 2005), our data showed that on days when participants experienced increased stress, they also experienced more negative affect. Thus, the data supported the notion that daily stress and daily negative affect are coupled with each other. Overall, these findings replicated the results of several previous studies (Bolger & Schilling; Marco & Suls, 1993; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Stawski et al., 2008; van Eck, Nicolson, & Berkhof, 1998) that have documented the association between stressful daily events and negative affect. Indeed, research suggests that long-term physiological and health-related responses to daily stress are influenced by adults’ emotional responses to such daily stressors (Pike et al., 1997; Seeman & Gruenewald, 2006; Stone, Marco, Cruise, Cox, & Neale, 1996). Therefore, gaining a better understanding of whether certain risk and resilience factors make individuals particularly vulnerable or resilient to the negative emotional consequences of daily stress is an important issue in this line of research.

Self-Concept Incoherence as a Risk Factor

Our data showed that SCI was positively associated with intraindividual variability in daily negative affect both before and after controlling for individuals’ mean level of stress (see Figure 2). This finding was consistent with our hypothesis that individuals with an incoherent self-concept would fluctuate more in negative affect from day to day than individuals with a more coherent self-concept. More importantly, the effect of SCI remained significant even after controlling for the effect of neuroticism (Bolger & Schilling, 1991; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Suls & Martin, 2005). The index of SCI, therefore, does not appear to be simply a proxy for neuroticism, but has an effect on daily negative affect above and beyond neuroticism.

Together with findings reported by other researchers (Showers et al., 1998; Zeigler-Hill & Showers, 2007), this finding supports the notion that an integrated and coherent self-concept structure represents a psychological resource that affects how individuals experience their daily lives. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has shown that greater SCI tends to be associated with greater intraindividual variability in daily negative affect, thus, further elucidating the role that SCI may play in long-term emotional adjustment and psychological well-being (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993, Study 2). Like a compartmentalized self-concept structure (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007; Zeigler-Hill & Showers), a highly incoherent self-concept seems to be a “hidden vulnerability” that may affect a person's overall well-being over time. Thus, the findings from this study provide a more contextualized understanding of SCI than previous research and point to potential mechanisms, such as greater within-person variability in negative affect and, hence, greater emotional instability, by which SCI may affect individuals’ psychological well-being.

We had also hypothesized that a higher level of SCI would be associated with a greater increase in negative affect in response to daily stress (i.e., increased stress reactivity). This hypothesis was not supported by the data, as evidenced by the non-significant SCI × Stress interaction. SCI, therefore, did not increase individuals’ reactivity to daily stress. This finding contrasts with the existing literature on the role of personality-related risk factors in at least two ways. First, this result is at odds with findings from studies that have shown that neuroticism tends to be associated with increased reactivity to daily stressors (cf. Bolger & Schilling, 1991; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004). Second, this finding is also inconsistent with findings from the study by Zeigler-Hill and Showers (2007) showing that college students with a more compartmentalized self-concept were significantly more reactive to daily events in terms of their state self-esteem than students with an integrated self-concept.

Although these discrepant findings cannot be easily reconciled, it is worth noting that the study by Zeigler-Hill and Showers (2007) differed from the current study with regard to several key features. For example, the current study focused exclusively on daily stressors and focused on the dependent variable negative affect, whereas Zeigler-Hill and Showers examined both positive and negative daily events and used as the dependent variable a measure of state self-esteem. Thus, these authors may have sampled the domain of daily events more comprehensively and, hence, may have increased their likelihood to show effects on a similar, albeit not identical outcome measure. In addition, Zeigler-Hill and Showers focused on another measure of self-concept structure that was related, but not identical, to our measure of SCI. Specifically, they considered whether individuals described their self-concepts using both positive and negative attributes within roles (i.e., evaluatively integrated) or whether they tended to describe themselves within roles using primarily positive or negative attributes (i.e., evaluatively compartmentalized). It is possible, therefore, that our discrepant findings reflect that the role of the self-concept in reactivity to daily events depends upon particularly nuanced aspects of the self-concept structure. For instance, high incoherence across roles may only be detrimental among adults who tend to describe themselves as primarily positive or negative (but not both) within roles Indeed, our finding that SCI is unrelated to stress reactivity is particularly surprising given that our data showed that adults’ SCI scores were positively associated with increased variability in negative affect. Together, these findings suggest that adults’ SCI scores are not only associated with greater variability in emotional states but also greater unpredictability in emotional states.

Finally, our hypothesis that age would moderate the association between SCI and reactivity to daily stress in terms of negative affect was not supported by the data. Thus, we failed to find support for the daily stress analog of an earlier cross-sectional finding showing that the association between SCI and measures of psychological well-being was moderated by age (Diehl et al., 2001). Rather, we found that the association between SCI and reactivity to daily stress in terms of negative affect was not significantly different across the age range studied. In the current study, therefore, a coherent self-concept was an equally important resource for young, middle-aged, and older adults.

Personal Control as a Resilience Factor

We found substantial support for the role of perceptions of personal control as a resilience factor in coping with daily stress (see Table 3). The data supported our hypothesis that perceived daily control would be significantly associated with daily negative affect. In particular, on days when individuals reported higher perceived control they reported lower negative affect. Although relatively little research focuses on daily perceptions of control, this finding is consistent with a large body of literature showing that perceptions of global control tend to be positively associated with a variety of positive outcomes and negatively associated with negative outcomes (Bandura, 1997; Lachman & Firth, 2004; Skinner, 1995).

In addition, we found that perceived personal control buffered reactivity to stress. Specifically, the association between daily stress and negative affect was stronger on days on which individuals reported low control compared to days on which they reported high control. This finding is similar to research by Neupert et al. (2007) and Ong et al. (2005). Specifically, Neupert et al. showed that adults who reported higher levels of trait-like perceived constraints and lower levels of trait-like perceived mastery tended to be emotionally and/or physically more reactive to daily stressors in different life domains (e.g., work, home, social network). Furthermore, in the only other study that has focused on daily perceptions of control, Ong et al. found that daily perceptions of control played a critical role in buffering psychological reactivity to daily stress among recently bereaved widows. The findings from the present study add to this body of research by documenting the positive effect of perceived personal control in the context of a 30-day study of ordinary daily stress and with a sample of adults covering the entire adult lifespan.

Our findings also showed that the association between daily perceived control and daily negative affect was moderated by age, as evidenced by the Age × Control interaction. Specifically, daily perceptions of control were more strongly associated with negative affect among younger adults. In particular, a low level of perceived daily control was associated with significantly more negative affect among younger adults compared to middle-aged or older adults. In general, this finding converges with results reported by Neupert et al. (2007). These authors showed that low levels of perceived control (i.e., high levels of perceived constraints) were related to poorer outcomes for individuals of all ages both in terms of their general daily well-being and in response to daily stress. Notably, however, Neupert et al. found that the association between perceived control and daily well-being in general was stronger among younger than older adults, and also that younger adults who perceived low control were more reactive to daily interpersonal stressors than older adults. When interpreted from a lifespan developmental perspective, the findings from the present study and from Neupert et al.'s work suggest that younger adults may be particularly vulnerable to perceiving low personal control in general and in their reactions to interpersonal stressors. Younger adults’ greater reactivity to interpersonal stressors when they perceive low personal control may be related to their desire for approval by significant others while at the same time lacking the appropriate interpersonal skills to cope with these stressors adequately. Indeed, younger adults’ lower level of perceived personal control and their greater sensitivity to perceiving low control may be the result of a more limited repertoire of coping skills as suggested by age comparative work on coping strategies (Diehl et al., 1996).

Finally, although we had hypothesized that the buffering effect of perceived control on the stress-affect association would significantly vary by level of SCI, the data from this study failed to support this hypothesis (see Table 3). In combination with the finding that SCI was positively associated with variability in daily negative affect, this result suggests that individuals with high SCI are similarly reactive to daily stress as individuals with low SCI at the same time as they are more variable in their daily negative affect. This also means that the greater variability in daily negative affect observed in adults with high SCI scores cannot be explained by them showing heightened reactivity to stress. Thus, this suggests that individuals with a more incoherent self-concept may overall be more psychologically disorganized, especially with regard to their emotions, than individuals with a more coherent self-concept. It may be this element of psychological disorganization and unpredictability with regard to emotional states that may make the lives of individuals with an incoherent self-concept difficult in terms of achieving well-being and adjustment.

Age as a Risk or Resilience Factor

Overall, our findings regarding the role of chronological age were more consistent with a conceptualization of age as a resilience factor rather than a risk factor. Not only was our hypothesis that older adults, in general, would have lower levels of average daily negative affect supported (cf. Charles et al., 2001), but age also moderated the effect of perceived control at the within-person level.

Consistent with our hypotheses, age did not moderate the effect of daily stress on adults’ daily negative affect. Thus, daily stress showed a similar association with daily negative affect regardless of a participant's age. On the one hand, this result was inconsistent with the findings reported by Mrozcek and Almeida (2004). Specifically, these authors reported findings showing that the association between daily stress and negative affect was significantly stronger in older adults compared to younger adults, potentially making older adults more vulnerable to the negative effect of daily stress. On the other hand, this result was consistent with findings reported by Stawski et al. (2008) and Uchino et al. (2006). For example, Uchino et al. reported that older adults showed less of an increase in negative affect during daily stress compared to younger adults. Similarly, Stawski et al. reported that although exposure to daily stressors was reduced in older adults, their emotional reactivity to the experienced daily stressors did not differ from that of younger adults. Thus, the findings from the present study contribute to the growing evidence that chronological age per se may not be a risk factor for becoming more vulnerable to the negative effects of daily stress, but that it may be other potentially age-related factors (e.g., more limited material and/or social resources) that increase older adults’ vulnerability to the effects of daily stress. This is important to note because the present study included individuals from age 18 through age 89 and examined their exposure to daily stress over a considerably longer period of time than previous studies (Mroczek & Almeida; Stawski et al.; Uchino et al.). Indeed, given research suggesting that older adults experience fewer stressors than younger adults (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Stawski et al.) studies such as this one, that examine adults’ stressors over a relatively long time period, may offer a more comprehensive and representative assessment of older adults’ daily stressors and of age differences in reactivity to stress.

To some extent, the findings from the present study also contribute to the general literature on emotion regulation in adulthood and old age. Although the debate about whether age is positively related to more effective emotion regulation (Carstensen et al., 2000; Labouvie-Vief, 2003) and whether different conceptualizations of emotion regulation may show different age-related trajectories is ongoing (Labouvie-Vief, Diehl, Jain, & Zhang, 2007), the findings from our study suggest that older adults were not less effective than younger adults in regulating negative affect in response to daily stress. Indeed, as Figure 1 shows, our findings support the position that older adults were less variable in their negative affect from day-to-day than younger adults (Charles et al. 2001; Griffin et al., 2006; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). Moreover, the association between age and intraindividual variability in negative affect still remained after we controlled for mean levels of daily stress. The association between age and variability in negative affect, therefore, was not due to age differences in stress exposure. Clearly, additional research is needed to address this general issue and to produce more conclusive findings. In particular, longitudinal measurement-burst designs, which repeat the intensive daily assessments at a later point in time, are needed to elucidate the role of short-term intraindividual variability with regard to long-term intraindividual change and interindividual differences in intraindividual change (Nesselroade & Ghisletta, 2003; Nesselroade & Ram, 2004).

Limitations

Although the present study examined the effects of age and personality-related risk and resilience factors in a sample covering the entire adult lifespan and over a longer time frame than other studies, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the objective of the present study was to examine the effects of age and risk and resilience factors across a broad range of daily stress events. Thus, the present findings do not speak to the possibility that some of the associations between negative affect and the risk and resilience factors may be different if domain-specific stressors are examined (see Neupert et al., 2007). Future analyses will address domain-specific variations in stress-outcome associations. Similarly, the present study was not able to address to what extent role-specific self-representations may potentially interact with the type of stressors the person experiences in this role because we did not assess stressors in a role-specific way. Again, this is an issue that may be fruitfully addressed in future studies.

Second, the current analyses focused on intraindividual variability in negative affect as the sole outcome variable. Although negative affect has been the most frequently used outcome variable in daily stress research (Bolger & Schilling, 1991; Marco & Suls, 2003; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004), there is also a growing understanding that assessments of negative affect should be complemented by assessments of positive affect or affect balance (Fredrickson, 1998; Pressman & Cohen, 2005). We intend to address this issue in detail in a separate paper, examining specifically the role that age and personality-related risk and resilience factors play in the regulation of positive and negative affect in response to daily stress (see Zautra, 2003).

Third, it is important to acknowledge that the present study sample consisted of fairly healthy community-residing adults with a relatively high level of education. Thus, this sample was biased in favor of more motivated, conscientious, and agreeable individuals (Scollon et al., 2003), which is very likely reflected in the high compliance rate (Bolger et al., 2003). Nonetheless, the occurrence of stressors in the health and physical well-being domain was similar to that found by Stawski et al. (2008) and the frequencies of stressors in other life domains were fairly comparable to those reported from a nationally representative sample of adults (Almeida et al., 2002).

Fourth, although the present study provided more specific support for the notion that an integrated and coherent self-concept structure is associated with positive outcomes, it is important to acknowledge that this association may only hold for adults in Western cultures (English & Chen, 2007; Suh, 2002). For example, in cross-cultural research that compared self-consistency in U.S. and Korean students, Suh showed that self-consistency was a significantly stronger predictor of students’ subjective well-being in the U.S. than in Korea. Thus, although self-consistency is important and considerably correlated with many positive outcomes in Western cultures, it is not as strongly tied to emotional well-being and adjustment in Eastern Cultures (Triandis & Suh, 2002).

Finally, although we were able to assess perceptions of control as a time-varying source of daily resilience for adults, constraints related to the testing burden associated with the SCI ratings prevented us from assessing SCI on a daily basis, and from considering its role as a time-varying daily risk factor in stress reactivity. Thus, this study is limited in the sense that our findings can only speak to the role of SCI as a general risk factor, but not as a daily risk factor. Analyses reported elsewhere (Diehl & Hay, 2007), however, have shown that adults were more reactive to daily stressors on days they endorsed negative self-attributes more strongly. Given this finding, it will be essential to develop a procedure to assess SCI in a context specific fashion to investigate in a more sensitive way how SCI is related to stress reactivity.

Conclusion

Using a daily diary design, the present study examined the associations between age, SCI, perceived personal control, and stress and variability in daily negative affect. The results indicate that risk and resilience factors influence daily well-being in complex ways. This is the case for both well-being in general and for well-being in terms of reactivity to stress. Our findings suggest that younger adults and adults with a more incoherent self-concept experienced greater emotional instability as well as higher average levels of negative affect over the 30 days of the study. However, whereas adults reported higher negative affect on days that they had increased stress, age and SCI did not play a role in reactivity to stress. Rather, reactivity to daily stress was buffered by daily perceptions of control, particularly among younger adults. In summary, the findings from this study suggest that personality-related risk and resilience factors influence daily well-being, day-to-day emotional stability, and reactivity to stress in varying ways across adulthood.

Figure 4.

Age as a moderator of the association between daily control and daily negative affect.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this article was supported by grant R01 AG21147 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/dev

We use the terms self-concept and self-representations interchangeably to refer to those attributes that are (a) part of a persony's self-understanding and self-knowledge, (b) the focus of self-reflection, and (c) consciously acknowledged by the person through language or other means of communication (see Harter, 1999).

Baird, Le and Lucas (2006) criticized the use of the SCD index from a methodological point of view. We addressed these authors’ criticisms in a different publication (Diehl & Hay, 2007) and showed that overall our findings did not change if we corrected the SCD index as suggested by Baird et al. (2006). Thus, we are confident that the SCD index represents a robust and useful operationalization of self-concept incoherence.

Some authors have suggested that the SCD index might only be a proxy for neuroticism and, thus, may be highly correlated with neuroticism. To examine this claim, we examined the correlation between the SCD index and neuroticism and performed a set of analyses in which we controlled for the effects of neuroticism. The correlation between SCD and neuroticism was r(239) = .45, p < .001. In terms of the multilevel analyses, the pattern of findings remained the same for all control analyses.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin CM. Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. Guilford; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Horn MC. Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The Daily Inventory of Stressful Experiences (DISE): An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird BM, Le K, Lucas RE. On the nature of intraindividual personality variability: Reliability, validity, and associations with well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:512–527. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RR. The self. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4th ed. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 680–740. [Google Scholar]

- Block J. Ego-identity, role variability, and adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1961;25:392–397. doi: 10.1037/h0042979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Schilling E. Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:355–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:136–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow S-M, Hamagami F, Nesselroade JR. Age differences in dynamical emotion-cognition linkages. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:765–780. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David J, Suls J. Coping efforts in daily life: Role of Big Five traits and problem appraisals. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:265–294. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:486–495. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]