Abstract

Clear and empirically supported diagnostic symptoms are important for proper diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders. Unfortunately, symptoms of many disorders presented in the DSM-IV-TR lack sufficient psychometric evaluation. In this study, an Item Response Theory analysis was applied to ratings of the 18 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms in 268 preschool children. Children (55% boys) in this sample ranged in age from 37 to 74 months; 80.4% were identified as African American, 15.1% Caucasian, and 4.5% other ethnicity. Dichotomous and polytomous scoring methods for rating ADHD symptoms were compared and psychometric properties of these symptoms were calculated. Symptom-level analyses revealed that, in general, the current symptoms provided useful information in diagnosing ADHD in preschool children; however, several symptoms provided redundant information and should be examined further.

Keywords: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Item Response Theory, assessment, behavior, DSM-IV-TR

ADHD Symptoms in Preschool Children: Examining Psychometric Properties using IRT

Over the last 20 years, significant concerns have been raised over the composition and construction of the symptoms of many psychological disorders. Several of the disorders specified in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were constructed based on committee decisions and, in some instances, without significant empirical support (Follette, 1996; Francis, Mack, First, & Jones, 1995). The importance of clear and empirically accurate diagnostic symptoms cannot be understated. Specifically, examination of the ways in which symptoms function in relation to their underlying latent construct is central to the development of a clear and accurate diagnostic system that can lead to increased diagnostic accuracy and improved treatment effectiveness (Jensen-Doss & Weisz, 2008). Recent research has supported the symptom composition of many psychological disorders, such as personality disorders (Balsis, Gleason, Woods, & Ottmanns, 2007; Feske, Kirisci, Tarter, & Pilkonis, 2007), conduct disorder (Gelhorn et al., 2009), Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adolescents (Gomez, 2008), oppositional defiant disorder (Gomez, Burns, & Walsh, 2008), and substance use disorders (Kirisci et al. 2006). Researchers continue to examine other disorders to determine symptom functioning as well as to examine differences in symptom fit across age groups (Saunders & Schuckit, 2006). One disorder in need of further symptom-level analysis is ADHD, particularly in younger children.

Diagnosis of ADHD

ADHD is a common neurobehavioral disorder that occurs in approximately 2 to 18% of the general child and adolescent population (Rowland, Lesesne, & Abramowitz, 2002). According to the DSM-IV-TR, the two main classes of behaviors that define ADHD are inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. To receive a diagnosis of ADHD, an individual must exhibit significant elevations in at least 6 of 9 Inattention symptoms (ADHD-Inattentive Type) or exhibit significant elevations in at least 6 of 9 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity symptoms (ADHD-Hyperactive Type); if a child exhibits the threshold number of symptoms for both Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity, he or she is diagnosed with ADHD-Combined Type. In addition to meeting a threshold number of symptoms, a child must show significant functional impairment in multiple settings as a result of the ADHD symptoms to be diagnosed with any of the three ADHD subtypes listed above. A clear delineation of diagnostic symptoms is necessary to (a) allow for more accurate classification of children displaying inattentive and/or disruptive behaviors, (b) improve outcomes for those individuals truly affected by the disorder and therefore needing treatment, and (c) improve research studies that evaluate the relation between ADHD and other problems such as academic difficulties and social relationships.

Construct Validity Concerns

Two central construct validity concerns are evident in the current diagnosis of ADHD. First, as with most DSM diagnoses, the symptoms of ADHD were determined by committee consensus, and there is limited information that has empirically determined whether the data provided by specific symptoms are necessary for accurate diagnoses to be made. It is possible that several symptoms are equally as indicative of ADHD. The inclusion of completely redundant symptoms is unnecessary and could result in scales that are not distributed uniformly. The increase in total score at one point along the latent continuum of the disorder may not equate to the same total score increase at another level along the latent continuum (e.g., the difference between a total score of 3 and 6 may not be equivalent depending on which items make-up that increase). It is also possible that specific behaviors are exhibited at different total levels of overall problem behavior (e.g., fidgeting in a seat may be less indicative of ADHD than verbal outbursts). Studies by Power et al (1998a, 1998b, 2001) support the notion that certain symptoms may be more indicative of a diagnosis of ADHD than are other symptoms. However, the information garnered from these studies is limited by the use of the committee consensus criteria to determine the presence or absence of a diagnosis. Examination of symptom properties without the predetermined diagnostic classification can enhance the examination of the functioning of different diagnostic symptoms. Further, the evaluation of potential symptom redundancy would enable researchers and clinicians to develop more succinct and accurate diagnostic techniques.

The second construct concern related to the current diagnosis of ADHD is how to determine the intensity at which a child’s behavior (e.g. fidgeting) should be classified as “abnormal behavior” rather than “normal behavior.” This concern is particularly salient in the use of ratings scales in which symptoms are rated across a continuum of severity (e.g., a 0-to-3 scale). Parent and teacher rating scales such as the Conner’s Rating Scales (Conners, 1997a, 1997b) and the ADHD Rating Scale-IV (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998) are designed for parents or teachers to rate the presence and severity of ADHD symptoms presented by a child. In general, symptoms on these measures are scored on a 0-to-3 scale with 0 indicating no presentation of the behavior and 3 indicating frequent presentation of the behavior. Symptoms ratings are usually dichotomized into categories denoting normal behavior (scores of 0 and 1) and denoting abnormal behavior (scores of 2 and 3), and then the number of symptoms endorsed is summed to determine if a child meets a specific threshold (for ADHD, 6 or more symptoms endorsed as abnormal). It is possible that the loss of information that results from dichotomizing can reduce clinical efficacy. Further, the decision to dichotomize into the common categories of 0 and 1 indicating no endorsement and 2 and 3 indicating endorsement may result in categorization that does not reflect the true underlying condition (i.e., ADHD diagnosis).

Addressing Diagnostic Concerns

To conduct high quality research in ADHD that addresses both construct validity concerns (i.e., determination of symptoms and evaluation of abnormality), it is necessary to examine how ADHD symptoms function in relation to each other and to the overall latent traits of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Further, it is important to ensure that measurement of these constructs is valid in all populations assessed. Recent work by Gomez (2008) laid the foundation for examining ADHD symptoms. Gomez determined that, in a sample of mostly elementary school age children rated by parents and teachers, the current diagnostic symptoms for both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity fit their respective constructs and had distinct differences in latent trait values for each response option. Further, Gomez found unique patterns of responses for both the inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scales. These findings indicate that the current diagnostic symptoms for ADHD are acceptable in a sample of elementary school children; however, these results are limited to this age-group of children and do not address concerns related to diagnosis of ADHD in younger children (i.e., preschool children).

It is especially important to examine the constructs of inattention and hyperactivity/ impulsivity in preschool children because of the dramatic developmental changes that occur in children during the first several years of life. Although the temporal stability of ADHD diagnoses in young children is high (Lahey et al., 2004; Loeber, 1991) and behavior problems beginning during preschool frequently continue into the teenage years (Campbell, 1995), different behavior patterns have been observed between elementary school age children and preschool children (Loughran, 2003). For example, preschool children often exhibit more hyperactive/impulsive behaviors than elementary school children, but these behaviors attenuate as children get older (e.g., elementary school children do not “climb excessively” as might a preschool child). Further, symptoms of inattention become more apparent as children get older, most likely due to the increased academic demands placed on them in school (Ruff & Rothbart, 1996; Spira & Fischel, 2005). Preschool children generally are not expected to perform tasks that might provide insight into their inattentive behaviors, such as remaining seated for extended periods of time.

Item Response Theory

Due to the potential for different presentations of ADHD symptoms in preschool-age versus older children, it is possible that ADHD symptoms have different psychometric properties across early to middle childhood. The term “psychometric properties” refers to the measurement of both how well a symptom fits its latent construct as well as the likelihood that symptom would be endorsed by a given individual. An empirical analysis of the psychometric properties of the DSM-IV-TR ADHD symptoms is needed to understand the appropriateness of the ADHD symptoms for preschool children. Item Response Theory (IRT; Lord & Novick, 1968) is a statistical tool well suited to answer this question (for a detailed explanation of IRT, please see Embretson & Reise, 2000; Hambleton, Swaminathan, & Rogers, 1991). IRT is a model-based method of latent trait measurement that relates the amount of an individual’s latent trait or attribute to the probability of endorsing a symptom (Hambleton et al, 1991). Specifically, multidimensional item response theory, which is used to model the relationships between two or more latent variables within one measure, is needed to examine the structure of the ADHD symptoms because although inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are separate constructs, they are not orthogonal. In fact, these two ADHD domains are highly correlated (r = .72; Erhart et al., 2008) and thus must be examined within one model.

Item Response Theory Background

In IRT, a person’s pattern of responses and the attributes specific to the individual symptoms are used to define the amount of a latent trait exhibited. IRT analyses are population independent, provide symptom specific information, and provide psychometric information across the continua of latent traits (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in this study). Although other techniques of examining symptom functioning such as Positive Predictive Power (PPP) and Negative Predictive Power (NPP) have been used in previous studies to identify symptoms which best differentiate between individuals with and without ADHD (Power, et al., 1998a; Power, et al., 1998b; Power, et al., 2001), PPP and NPP assume initial diagnostic status to be accurate. IRT examines the symptom functioning in relation to the latent trait, which is more consistent with the recognition that Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity are continuous traits (Lahey, Pelham, Loney, Steve, & Wilcutt, 2005).

Item Response Theory Parameters

IRT analysis yields parameters for both an individual’s latent trait and symptom functioning. The parameters that describe symptom functioning are the discrimination parameter (a) and the difficulty parameter (b). The discrimination parameter is a measure of how well a symptom differentiates between individuals above and below that point on the continuum of the latent trait. The difficulty parameter is a measure of how much of a latent trait is necessary for a response to be endorsed and can be interpreted as the severity of symptomology when that symptom is endorsed. In a four-option Likert scale, as is the case in many ADHD symptoms rating scales, there are three difficulty parameters: b1, b2, and b3. These are the points along the latent trait spectrum at which a specific response option would be endorsed 50% of the time for an individual with a given latent trait; b1 is the amount of latent trait that is required to move from a score of 0 on the rating scale to a score of 1; b2 is the amount of latent trait required to move from 1 to 2; and b3 is the amount required of latent trait required to move from 2 to 3. Elevated discrimination (a) values suggest that symptoms are able to differentiate between levels of latent trait at the specified difficulty. In addition to the discrimination (a) and difficulty (b) parameters, which describe symptom functioning across all individuals, IRT analysis yields a theta value that is unique to each individual and is the position along the latent trait continuum where the individual is more likely to endorse all symptoms with difficulty values below his or her theta and less likely to endorse symptoms above that point. For example, a very hyperactive/impulsive child would display a high theta value, meaning he or she would be more likely to be rated as “abnormal” on all 9 hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.

Reliability

Within IRT analyses, there are two indices of reliability. Item Information Functions (IIFs) show the amount of information obtained from individual symptoms at all points across the spectrum of behavior and can be graphed using the discrimination and difficulty parameters.1 Higher levels of information indicate less measurement error. The sum of the IIFs from a test is called the Test Information Function (TIF), which can be used to examine how a set of symptoms function together over the latent-trait spectrum to provide a reasonable measure of that latent trait. The TIF is an index of the reliability of the test across the latent trait spectrum.

Current Study

Not knowing how much weight each ADHD symptom carries or what defines significant symptomology can result in inaccurate cut points for ADHD symptoms that may result in misdiagnosis of this disorder and, ultimately, lead to poorer treatment outcomes. In future revisions of the DSM, it will be important to justify decisions with empirical research. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to use IRT first to compare the current methods of scoring symptoms (i.e., dichotomous vs. polytomous scoring of ADHD rating forms) and then to provide empirical support for ADHD symptoms by examining symptom parameters.

Method

Participants

Data were collected in public and private preschools serving children from families with low- to middle-socioeconomic statuses as part of a larger intervention study. Participation in the study was not restricted based on academic or behavioral levels. Children ranged in age from 37 months to 74 months, with a mean age of 53.2 months (SD = 6.0 months). Of the 268 participants in this study, 80.4% were identified as African American, 15.1% Caucasian, and 4.5% other. The sample was 55.0% boys and 45.0% girls.2 Parental consent was obtained for each child prior to the start of the assessment. Although there is no standard method for conducting a priori power analysis for IRT to determine necessary sample size, Embretson and Reese (2000) suggest a minimum of approximately 250 subjects for a graded response model.

Measure and Procedure

The ADHD Rating Scale-IV: School Checklist (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998) was used to assess the children on the ADHD symptoms. This measure contains each of the 18 DSM-IV-TR symptoms for ADHD (9 inattention symptoms, 6 hyperactivity symptoms, and 3 impulsivity symptoms). Each child was rated on how often he or she exhibited the behavior indexed by each symptom on a scale from 0 (never or rarely) to 3 (very often).

Ratings were completed by children’s small-group instructors, who were hired by the primary investigator to provide literacy intervention as part of a larger research project. Small-group instructors spent 20 minutes per day, 5 days per week, for a period of 3 months, with each child in small group settings (3–5 children per group). All instructors were individuals who were either working toward or had completed an undergraduate degree in psychology, communication disorders, special education, or a related field. There were a total of 15 different raters.3

Analytic Approach

Two primary stages of analysis were conducted. In the first stage, the information provided by the dichotomous and polytomous scoring systems was assessed. Although the symptoms were scored initially on a 4-point Likert scale, dichotomous scoring of the symptoms was also conducted because dichotomization is a common practice in many clinical settings (i.e., symptoms rated as 0 and 1 were set equal to 0 [symptom absent] and symptoms rated as 2 and 3 were set equal to 1 [symptom present]). To calculate symptom parameters for the 18 DSM-IV-TR ADHD symptoms, a multidimensional IRT analysis was conducted using Mplus version 5.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2008). To calculate Test Information Functions (TIFs) and Item Information Functions (IIFs) a 2-parameter logistic model was applied to the dichotomous data and Samejima’s graded response model was applied to the polytomous data using MODFIT (Stark, 2000). TIFs were compared to determine which scoring system provided the most information over the entire spectrum of the latent traits. In the second stage of analysis, the individual symptoms within the inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity factors were examined and individual symptom parameters (i.e., difficulty and discrimination parameters and IIFs) were calculated to determine if symptoms provided redundant information.

Results

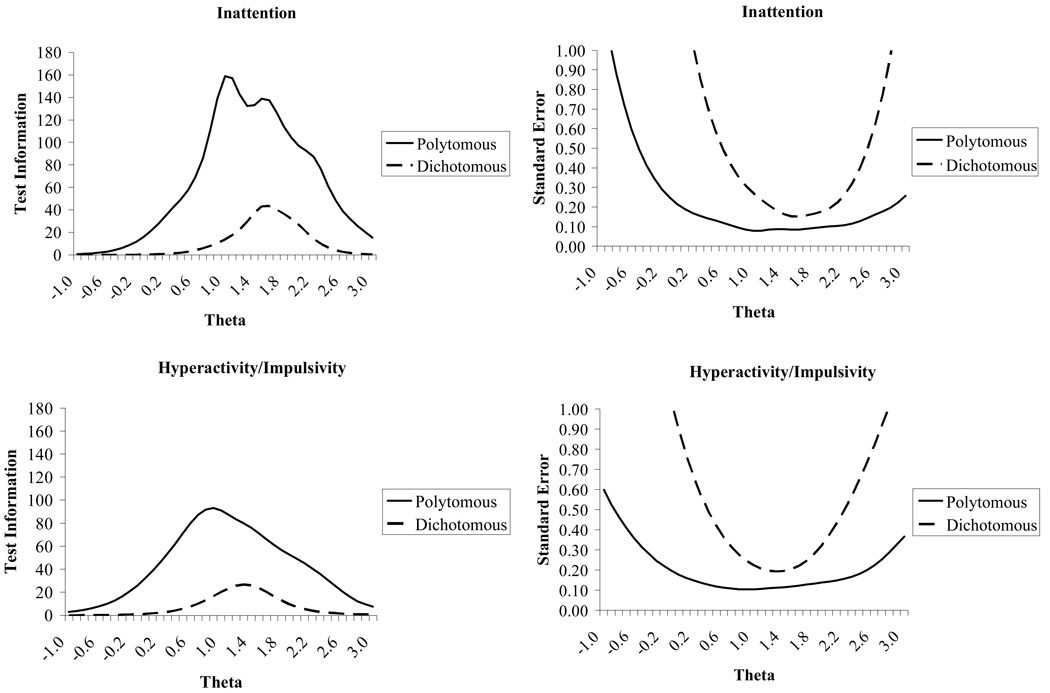

TIFs for the latent traits of both inattention (top panel) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (bottom panel) are presented in Figure 1. For both latent traits, the polytomously scored data provided more information across a broader range of the latent traits than did the dichotomously scored data. Additionally, for both latent traits, the range of theta for which there was acceptable standard error (i.e., < .32, which is equal to an internal consistency of .90) was wider for polytomously scored data than for dichotomously scored data. Although both scoring methods are acceptably reliable, the polytomously scored data provided more accurate information for individuals at the extreme ends of ADHD-spectrum behavior. Specifically, acceptable standard errors across different ranges of theta values were as follows: Inattention, dichotomous = .90 to 2.20; polytomous = −.30 to more than 3.00; Hyperactivity/Impulsivity, dichotomous = .70 to 1.80; polytomous = −.50 to 2.90 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Test Information Functions and standard error functions for inattention (top) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (bottom) symptoms scored dichotomously and polytomously. High levels of information and low standard errors indicate high reliability of the scale a given point along the latent trait.

The total scores within inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity for the two scoring techniques were highly correlated (Inattention r = .94, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity r = .92). Due to these high correlations between scoring methods and in conjunction with the fact that the polytomous scoring method provided more information over a broader range of theta, further analyses only utilized the polytomously scored data.

Symptom Parameters

Inattention

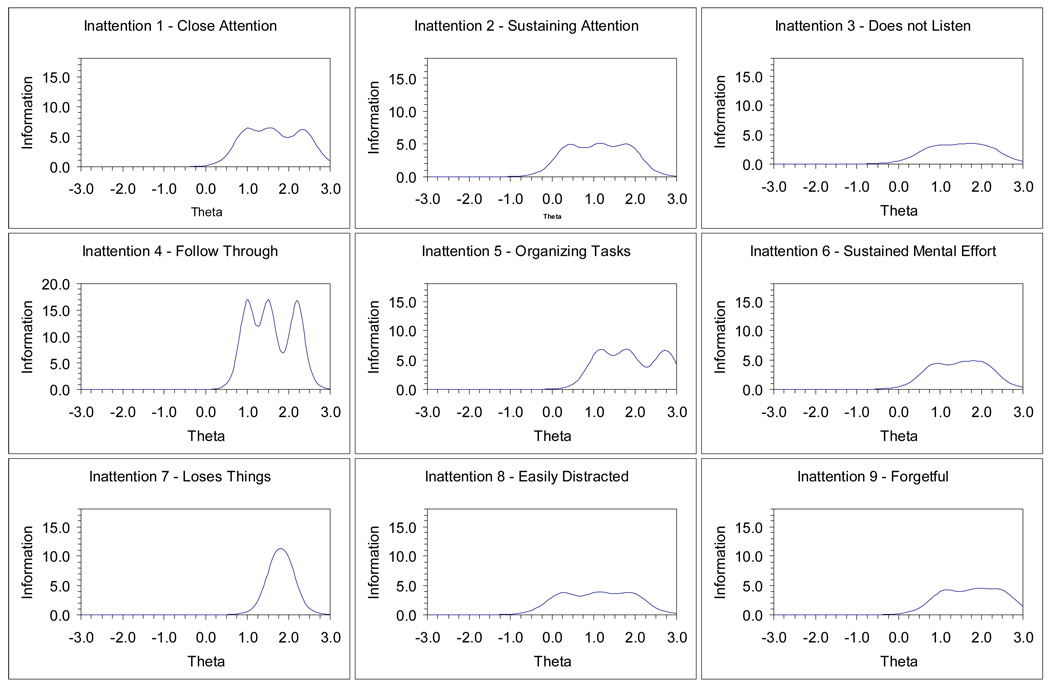

Symptom parameters for each of the nine Inattention symptoms are presented in Table 1. All nine inattention symptoms differentiated well between individuals above and below the symptoms difficulty parameters. Symptoms with the highest discrimination parameters were Symptoms 1 (“close attention”), 4 (“follow through”), 5 (“organizing”), and 7 (“loses things”). The IIFs, which are calculated using both the discrimination and difficulty parameters, for each of the inattention symptoms are presented in Figure 2. The information values for each symptom at varying theta values are presented in Table 2. Symptom 4 (“follow through”) provided the most information at each of the difficulty values and across a relatively broad range of the latent trait. Comparatively, Symptoms 1, 2, 5, and 7 provided a moderate amount of information across the range of difficulty values. The remaining symptoms provided less information.

Table 1.

Symptom Parameters for DSM-IV-TR Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms

| Symptom Parameters |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Discrimination | Difficulty 1 | Difficulty 2 | Difficulty 3 |

| Inattention | ||||

| 1. Fails to give close attention to details | 2.90 | .97 | 1.58 | 2.35 |

| 2. Difficulty sustaining attention | 2.57 | .40 | 1.14 | 1.83 |

| 3. Does not listen | 2.02 | .86 | 1.56 | 2.08 |

| 4. Does not follow through on instructions | 4.81 | 1.00 | 1.51 | 2.20 |

| 5. Has difficulty organizing tasks | 3.02 | 1.14 | 1.81 | 2.73 |

| 6. Avoids tasks requiring sustained mental effort | 2.41 | .87 | 1.59 | 2.05 |

| 7. Loses necessary things | 3.64 | 1.68 | 1.94 | --* |

| 8. Easily distracted | 2.25 | .24 | 1.13 | 1.90 |

| 9. Forgetful in daily activities | 2.37 | 1.11 | 1.86 | 2.46 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | ||||

| 10. Fidgets or squirms | 1.79 | .19 | 1.26 | 2.03 |

| 11. Leaves seat | 2.44 | .55 | 1.12 | 1.77 |

| 12. Runs about or climbs excessively | 2.75 | .86 | 1.28 | 1.92 |

| 13. Difficulty playing quietly | 2.88 | .84 | 1.47 | 2.29 |

| 14. “On the go” or “driven by a motor” | 2.33 | .81 | 1.37 | 1.75 |

| 15. Talks excessively | 1.04 | .55 | 1.65 | 3.15 |

| 16. Blurts out answers | 1.01 | .42 | 1.73 | 2.79 |

| 17. Difficulty awaiting turn | 1.94 | .24 | 1.14 | 1.94 |

| 18. Interrupts or intrudes on others | 1.88 | .42 | 1.18 | 1.99 |

Note. N = 268.

This parameter could not be calculated because no child was rated as a “3”on this symptom.

Figure 2.

Item Information Functions for polytomously scored inattention symptom, shown by individual symptoms. High levels of information indicate high reliability a given point along the inattention latent trait.

Table 2.

Estimated Trait Values for each Symptom across the Range of the Latent Trait

| Estimated Trait |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | −3.0 | −2.0 | −1.0 | −0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Inattention | |||||||||||

| 1. Fails to give close attention to details | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .20 | 1.98 | 6.40 | 6.44 | 4.79 | 5.40 | .93 |

| 2. Difficulty sustaining attention | .00 | .00 | .04 | .36 | 2.44 | 4.91 | 4.88 | 4.67 | 4.22 | .92 | .11 |

| 3. Does not listen | .00 | .00 | .02 | .11 | .55 | 2.07 | 3.26 | 3.44 | 3.39 | 1.84 | .46 |

| 4. Does not follow through on instructions | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | 1.12 | 16.99 | 17.04 | 10.15 | 4.73 | .09 |

| 5. Has difficulty organizing tasks | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .07 | .91 | 5.87 | 5.79 | 5.60 | 5.18 | 4.22 |

| 6. Avoids tasks requiring sustained mental effort | .00 | .00 | .01 | .06 | .45 | 2.49 | 4.39 | 4.63 | 4.73 | 2.00 | .33 |

| 7. Loses necessary things | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .56 | 7.31 | 9.78 | 1.10 | .05 |

| 8. Easily distracted | .00 | .00 | .13 | .78 | 3.02 | 3.45 | 3.78 | 3.59 | 3.62 | 1.23 | .21 |

| 9. Forgetful in daily activities | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .18 | 1.19 | 3.94 | 3.96 | 4.50 | 4.23 | 1.48 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | |||||||||||

| 10. Fidgets or squirms | .00 | .01 | .23 | .90 | 2.15 | 2.25 | 2.33 | 2.58 | 2.51 | 1.45 | .44 |

| 11. Leaves seat | .00 | .00 | .03 | .21 | 1.43 | 4.47 | 4.86 | 4.50 | 3.50 | .76 | .10 |

| 12. Runs about or climbs excessively | .00 | .00 | .00 | .04 | .38 | 2.89 | 6.31 | 5.49 | 5.42 | 1.30 | .14 |

| 13. Difficulty playing quietly | .00 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .37 | 3.19 | 6.09 | 6.31 | 4.76 | 4.68 | .70 |

| 14. “On the go” or “driven by a motor” | .00 | .00 | .01 | .09 | .60 | 2.80 | 4.41 | 4.73 | 3.19 | .74 | .11 |

| 15. Talks excessively | .01 | .03 | .18 | .37 | .63 | .85 | .91 | .92 | .86 | .83 | .85 |

| 16. Blurts out answers | .01 | .04 | .22 | .42 | .66 | .81 | .83 | .85 | .87 | .85 | .75 |

| 17. Difficulty awaiting turn | .00 | .01 | .17 | .80 | 2.36 | 2.78 | 2.93 | 2.89 | 2.81 | 1.28 | .31 |

| 18. Interrupts or intrudes on others | .00 | .00 | .11 | .48 | 1.68 | 2.80 | 2.86 | 2.75 | 2.71 | 1.40 | .37 |

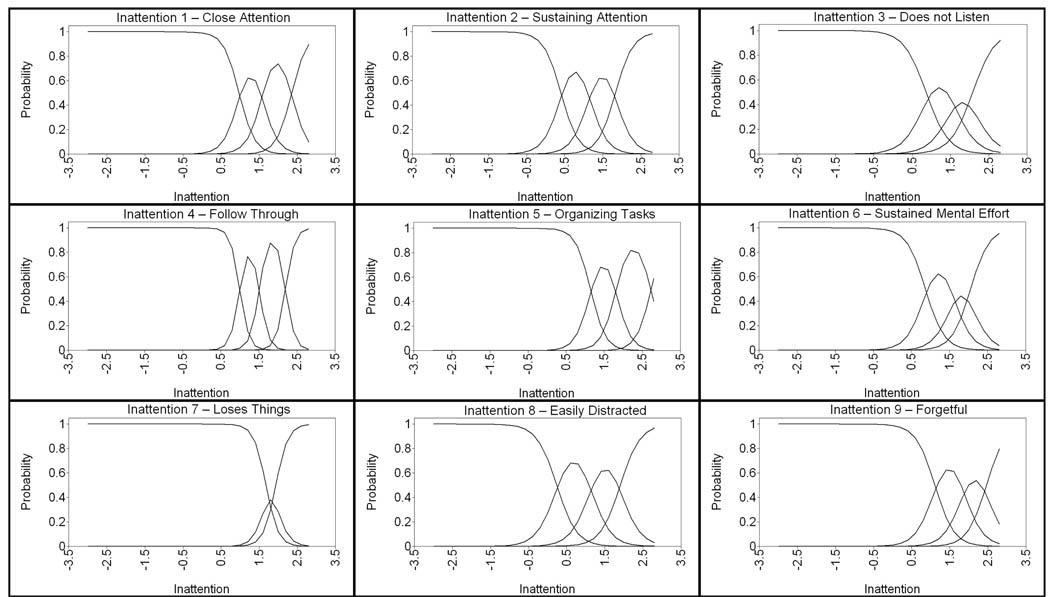

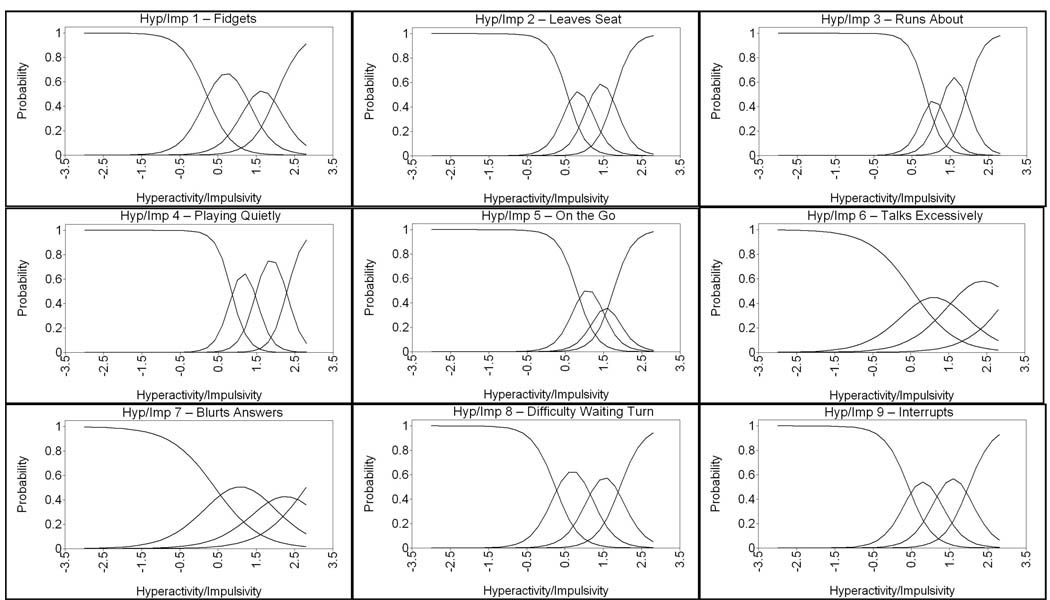

Two aspects of the difficulty parameters were examined. The first aspect was the change in difficulty by response option within symptom (e.g., comparison of the three difficulty values--b1, b2, and b3--for each symptom). Difficulty parameters increased by approximately .50 to .80 degrees of theta between each response option, which indicated that there was a reasonable and consistent increase in theta between response options. This is best illustrated through an Item Characteristic Curve (ICC). The ICC is a graph of the likelihood a response being endorsed across the range of theta values. ICCs for each of the nine inattention symptoms are presented in Figure 3. With the exception of Symptom 7, all ICCs showed distinct shifts (i.e., visible peaks for each response option that are not overlapped by the other response curves) between response options. Symptom 7 (“Loses things”) showed little distinction between responses of 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Item Characteristic Curves for inattention symptoms. Each curve indicates the likelihood for a level of a symptom to be endorsed at a given level of the inattention latent trait. The first curve for each symptom is for a response of 0, the second curve is for a response of 1, and so forth.

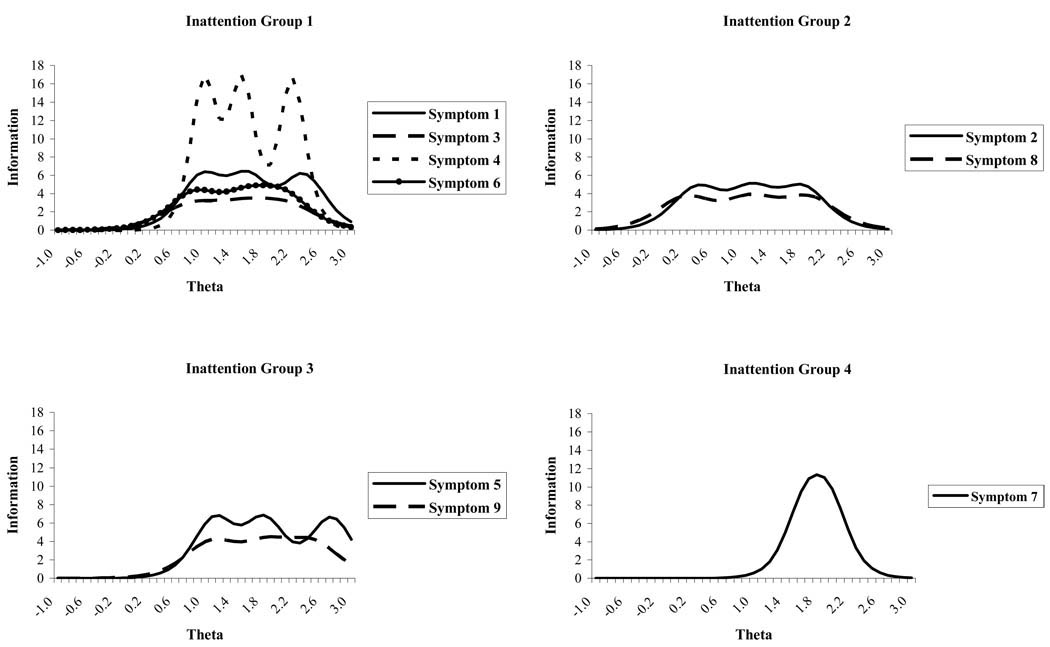

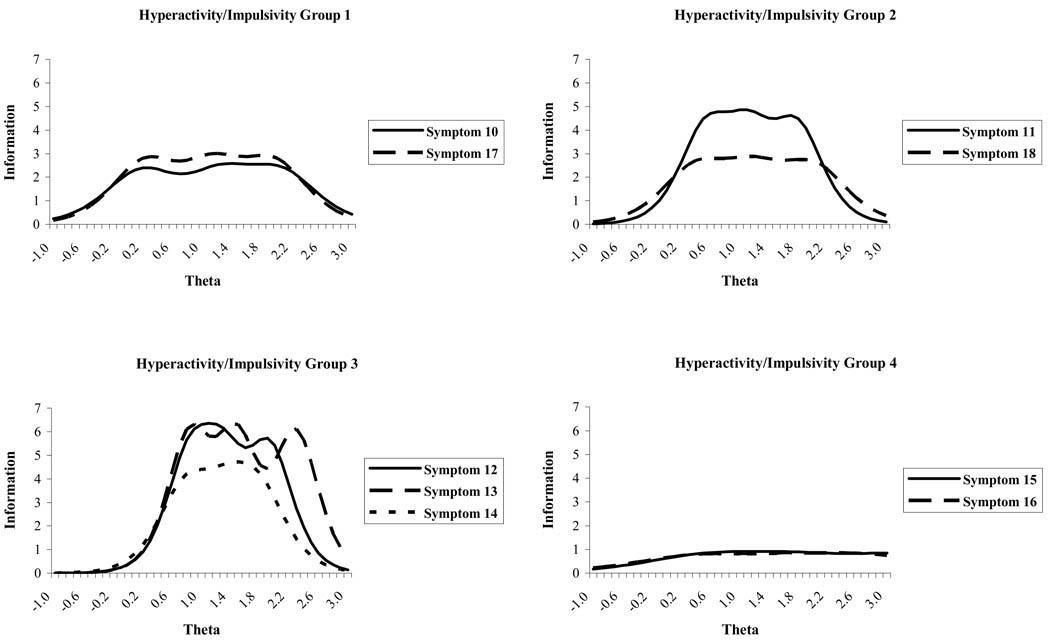

The second aspect of the difficulty parameters examined was the range of difficulties within response options (e.g., range of difficulties for a response of 1 to all symptoms, 2 to all symptoms, or 3 to all symptoms). This aspect is important because it shows the variability in difficulty levels of comparable responses to different symptoms. This type of information is not captured, and may be lost completely, when only raw scores are examined. The difficulty parameters within a response option (i.e., the first column of difficulty parameters) were not homogenous, and they spanned a substantial range of theta values (or levels of the latent trait of inattention; approximately 1.44 for difficulty 1, .81 for difficulty 2, and .90 for difficulty 3), suggesting that similar scores on the various inattention symptoms are indicative of different latent trait levels. The lack of homogeneity of difficulties within a column indicates that similar responses to symptoms do not necessarily provide the same information or indicate comparable levels of the latent trait. There are a number of symptoms, however, that provide similar difficulties across the response options. Inattention symptoms were separated into four symptoms groups based on the similarity of their difficulty parameters. The reason for grouping items is to identify which symptoms may provide redundant information, as evidenced by identical IIFs. Graphs of the IIFs for the symptoms in each of the four groups are presented in Figure 4. Group 1 consisted of Symptoms 1, 3, 4, and 6. Of these symptoms, Symptom 4 provided the most information. Group 2 consisted of Symptoms 2 and 8; both of these symptoms provided comparable information. Group 3 consisted of Symptoms 5 and 9; both of these symptoms provided comparable information. Group 4 consisted of only Symptom 7. This symptom was unique, in part, because no child was rated as a 3 on this symptom.

Figure 4.

Item Information Functions for polytomously scored inattention symptoms, shown by symptom groups. Inattention symptoms were separated into four symptoms groups based on the similarity of their difficulty parameters. Group 1 consisted of Symptoms 1, 3, 4, and 6. Group 2 consisted of Symptoms 2 and 8; both of these symptoms provided comparable information. Group 3 consisted of Symptoms 5 and 9. Group 4 consisted of only Symptom 7. Symptoms with higher Item Information Functions than other symptoms in the group are more reliable symptoms.

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity

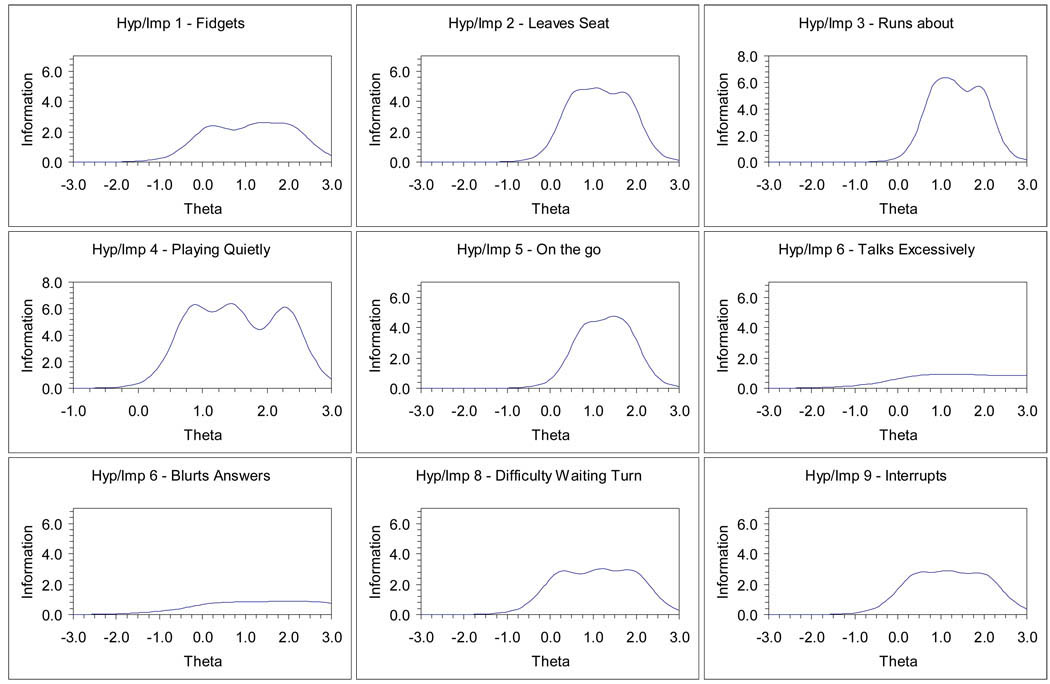

Symptom parameters for each of the nine hyperactivity/ impulsivity symptoms are presented in Table 1. The IIFs for each of the hyperactivity/ impulsivity symptoms are presented in Figure 5. Information values for each symptom for varying theta values, or levels of the latent trait, are presented in Table 2. Overall, Symptom 13 (“playing quietly”) provided the most information across a broad range of the latent trait. Symptoms 11, 12, and 14 also provided substantial amounts of information. Symptoms 10, 17, and 18 only provided a moderate amount of information. Symptom 15 and 16 provided relatively little information at any point along the continuum of the latent trait, compared to the other symptoms. The discriminations for the hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms were generally moderate to large, indicating that all nine symptoms differentiated well between individuals above and below the each symptom’s difficulty parameters. However, Symptoms 15 (“talks excessively”) and 16 (“blurts out answers”) barely met the acceptable level of 1.0. This is reflected in low slopes on the ICCs for these two symptoms, which are presented in Figure 6. Symptoms with the highest discrimination parameters were Symptoms 11 (“leaves seat”), 12 (“runs about”), 13 (“difficulty playing quietly”), and 14 (“on the go”).

Figure 5.

Item Information Functions for polytomously scored hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, shown by individual symptoms. High levels of information indicate high reliability a given point along the hyperactivity/impulsivity latent trait.

Figure 6.

Item Characteristic Curves for hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms. Each curve indicates the likelihood for a level of a symptom to be endorsed at a given level of the hyperactivity/impulsivity latent trait. The first curve for each symptom is for a response of 0, the second curve is for a response of 1, and so forth.

Unlike the inattention symptoms, the difficulty parameters for the hyperactivity/ impulsivity symptoms increased by varying amounts (theta values between .42 and 1.31) across response options as opposed to the stable .40 to .80 change for inattention symptoms. For example, there was only a change of 0.42 standard deviations between b1 and b2 for Symptom 12, but there was a 1.31 standard deviation difference between b1 and b2 for Symptom 16. All of the ICCs show distinct shifts between response options; however, Symptom 14 (“on the go”) shows only a minimally distinct ICC for a response of 2.

Similar to the inattention symptoms, although less dramatic, the hyperactivity/impulsivity difficulty parameters within a response level (i.e., b1, b2, and b3) spanned a large range of the latent trait. However, the high and low ends of each difficulty column did not overlap. There was a distinct separation between the highest difficulty for b1 (.86 for Symptom 12) and the lowest difficulty for b2 (1.12 for Symptom 11). The difference was less pronounced between the b2 and b3, where the highest difficulty parameter for b2 (1.73 for Symptom 16) was only slightly less than the lowest difficulty parameter for b3 (1.75 for Symptom 14). Although the difficulties for comparable responses span a wide range of the latent trait (i.e., theta), there appears to be some inconsistency between difficulty values for different responses (e.g., a response of 1 for a symptom does not necessarily have a similar difficulty as a response of 2 for another symptom).

Using the polytomous data, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity symptoms were separated into four groups based on the similarity of their difficulty parameters (see Figure 7). Group 1 consisted of Symptoms 10 and 17, which both provided comparable information about the latent trait. Group 2 consisted of Symptoms 11 and 18; Symptom 11 provided more information than Symptom 18. Group 3 consisted of Symptoms 12, 13, and 14; these three symptoms provided more information than symptoms from any other group. Finally, Group 4 consisted of Symptoms 15 and 16, which did not provide significant information about the latent trait.

Figure 7.

Item Information Functions for polytomously scored hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, shown by symptom groups. Hyperactivity/Impulsivity symptoms were separated into four groups based on the similarity of their difficulty parameters. Group 1 consisted of Symptoms 10 and 17. Group 2 consisted of Symptoms 11 and 18. Group 3 consisted of Symptoms 12, 13, and 14. Group 4 consisted of Symptoms 15 and 16. Symptoms with higher Item Information Functions than other symptoms in the group are more reliable symptoms.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the current ADHD diagnostic symptoms by obtaining psychometric data on the symptoms for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in preschool children and to compare dichotomous and polytomous scoring methods. Examination of psychometric information for the data obtained in this study revealed that although all symptoms fit their respective latent traits well (i.e., had acceptable discrimination parameters), several symptoms within each trait provided redundant information for a given level of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity severity (i.e., had comparable difficulty parameters). These findings also compare favorably to findings by Gomez (2008) for adolescents. The similarities in symptom parameters between age groups and across different types of raters (i.e., Gomez used ratings by parents and classroom teachers whereas, this study used ratings by intervention instructors) appear to be robust and thus can be interpreted with confidence. These findings are further bolstered by the similarities between symptom b parameters in this study and symptom PPP in Power et al., (2001). Those symptoms with the highest b parameters were the same symptoms with high PPP. Results also suggested that the information provided by the polytomous scoring method was more detailed and generally more useful for obtaining the severity of ADHD than the information provided by the common dichotomous scoring method. Overall, the findings from this study enhance the body of knowledge regarding the ADHD diagnostic symptoms in young children and can be used in refinement of these symptoms in future revisions of the DSM.

Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties

Diagnostic Categorization

In evaluating the psychometric properties of the ADHD symptoms, it is important to consider the overall purpose for using these symptom parameters. As previously mentioned, in IRT, there is not a single reliability score for an entire scale. Reliability, or standard error, is calculated for all levels of symptom severity on a scale (e.g., a scale can be very reliable at the high of the scale and not reliable at the low end of the scale). Inclusion of a symptom only improves the reliability of the scale near the difficulty values of that symptom. For example, including a symptom that has a high difficulty score only improves the reliability of the scale at the high end of the latent trait; there would be no improvement of reliability at the low end of the latent trait. If multiple symptoms with comparable difficulty parameters were included in the construction of a scale, the reliability around the level of symptom severity indicated by the difficulty parameter would be high. The resulting scale would reliably categorize individuals with symptom severity above and below the difficulty values of the redundant symptoms; however, the scale would not provide reliable information regarding the severity of symptomology.

If the purpose of examining these parameters is to develop a diagnostic measure that fits the medical model of the DSM where individuals are categorized into diagnosis versus no diagnosis, then symptoms with overlapping parameters are ideal. However, no evidence has identified empirically the symptom severity of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity at which a diagnosis should be made. It is difficult to obtain this formation without first having a reliable measure of the range of the inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity latent traits. Thus, the focus of this part of the discussion will be on refinement of the diagnostic symptoms for assessing the range of the inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity constructs. Issues surrounding the determination of the diagnostic cut-point will be discussed later.

Continuous Measurement

To develop a scale of symptoms that measures the broad range of the latent trait of ADHD, symptoms with difficulty parameters across the range of ADHD severity (i.e., symptoms with both low and high difficulty parameters) should be retained from the current symptom list and those symptoms that provide little unique information should be removed (e.g., Inattention Symptom 3 – Does not listen). Although symptoms that provide redundant information improve reliability of the scale at a specific point along the latent trait continuum, they can result in a non-uniform measure of the latent trait. In most clinical settings, endorsement of six inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms is required for a diagnosis of ADHD. This diagnostic system imposes categorical judgment on a continuous variable. The use of multiple symptoms that provide redundant information would result in a “double-counting” of one indicator, which could artificially inflate the symptom count. A more tangible example of this would be in an education setting. If a mathematics test were constructed with several items that span the range of mathematical ability, none of which provided redundant information, the test would be a uniform measure of mathematics ability across the range of the latent trait. If the test had many items with identically low difficulty parameters (i.e., easy items), however, the test scores would be inflated artificially at the low end of the scale (e.g., the sum of correct answers to five easy items are not equivalent to a correct answer on a more difficult item). Identification and removal of similar items at the low end of the scale (i.e., items that provide comparable information to other items) would result in a uniform measure of mathematics ability. Utilizing the current symptoms for the constructs of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, several symptoms provide redundant information, which results in the potential to artificially inflate the overall severity score for these dimensions.

Types of Symptoms

Symptoms should be grouped together based on the similarities of their difficulty parameters to evaluate the similarity of symptoms within a construct, as was done in Figure 4 and Figure 7. In determining which symptoms with similar difficulty parameters should be considered for removal, three types of symptoms can be found. The first type of symptom is one that does not provide adequate information (i.e., discrimination parameters equal to or below 1.0). The second type of symptom is one that provides adequate information but is less informative than other symptoms with comparable difficulty parameters. The third type of symptom is one that provides adequate information identical to other symptoms with comparable difficulty parameters.

If the purpose of psychometric property evaluation is to develop a diagnostic construct that assesses the range of the latent trait then the most informative symptoms that have difficulty parameters spanning the range of the latent trait should be retained. Symptoms that do not provide adequate information (first type mentioned above) or less information than symptoms with comparable difficulty parameters (second type mentioned above) should be considered for removal from future revisions of the DSM. Symptoms that have redundant information (third type mentioned above) should be evaluated further based on their longitudinal stability and differential symptom functioning (e.g., parameter differences based on sex, ethnicity, age, and rater type) to determine which symptoms should be retained (i.e., symptoms that yield comparable information with little evidence of differential symptom function would be preferred over symptoms with evidence of differential symptom functioning).

Evaluation of inattention symptoms

In the specific case of the inattention symptoms assessed in these analyses, all symptoms of this construct had high discrimination parameters and provided useful information about inattentive behaviors. Thus, there were no symptoms that should be considered for removal based on providing inadequate information. As previously discussed, the inattention symptoms were separated into four groups based on their difficulty parameters. In Group 1, Symptoms 1, 3, 4, and 6 all had comparable difficulty values. Symptoms 1, 3, and 6 fit in the second category of symptoms that had acceptable discrimination parameters but are not as good as other comparable symptoms. Symptom 4 provided significantly more information than all the other symptoms in this group due to its very high discrimination parameter. Thus, Symptom 4 is a more informative symptom and should be considered for retention in future revisions of the DSM prior to consideration of Symptoms 1, 3, and 6. In Group 2 (Symptoms 2 and 8) and Group 3 (Symptoms 5 and 9), symptoms had comparable discrimination and difficulty parameters and provided redundant information. Because these symptoms provided redundant information, one symptom from each group may be unnecessary in the development of a measure of the construct of inattention that spans the entirety of the latent trait. Finally, only one symptom fit into Group 4, and thus, no comparison to other symptoms could be made; further evaluations with broader samples of children should be used to obtain stronger psychometric information about this symptom. Although certain inattention symptoms (e.g., Symptom 4) provide significantly more information than other comparable symptoms, several of the inattention symptoms provided nearly or completely redundant information. Further evaluation of the redundant symptoms is needed to determine which symptoms provide the most stable information over time.

Evaluation of hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms

The hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms also exhibited a range of fit within the developmental continuum of the latent trait. As was the case with the inattention symptoms, the hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms were divided into four groups based on their difficulty parameters. Symptoms 15 and 16 provide relatively little information about hyperactive/impulsive behaviors; so, it may be reasonable to remove these two symptoms when evaluating preschool children for a diagnosis of ADHD. In Group 1, both Symptom 10 and 17 provided nearly completely redundant information; thus, an individual displaying a specific level of hyperactivity/impulsivity is likely to receive the same rating on both symptoms; further evaluations of the symptoms is needed to determine which of these two symptoms should be retained. In Group 2, although Symptoms 11 and 18 had comparable difficulty parameters, Symptom 11 had a significantly higher discrimination parameter and thus provided more unique information; Symptom 11 should be considered for retention in future revisions of the DSM prior to consideration of Symptom 18. In Group 3, all three symptoms (12, 13, & 14) had high discrimination parameters; however, Symptoms 12 and 13 provided marginally more information than did Symptom 14. As with the inattention symptoms, several hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms provided redundant information and require further evaluation to determine which symptoms should be removed.

Future Directions

Stability of symptoms over time

Before removing any symptoms from the ADHD diagnosis in future revisions of the DSM, it is important to examine the longitudinal change in the utility of each diagnostic symptom, as a symptom may become more or less relevant over time (e.g., “climbs excessively” may be more indicative of ADHD for elementary children than for preschool children). Rather than removing symptoms altogether, it may be prudent to specify which symptoms should be considered at different ages. In comparing the results of this study with those of elementary age children in Gomez (2008), there was little variation in the rank ordering of symptom difficulty parameters. Only Inattention Symptom 3 (“does not listen”) appeared to be an indicator of more severe inattention in adolescents than in preschoolers. Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Symptom 15 (“talks excessively”) appeared to be an indicator of more severe hyperactivity/impulsivity in preschoolers than in adolescents. The primary differences between the findings from Gomez (2008) and the current study are in the hyperactivity/impulsivity discrimination parameters. The impulsivity symptoms (Symptoms 16, 17, and 18) have higher rank order discrimination parameters in adolescents than in preschool children. Caution should be exercised in attributing differences in these results and those of Gomez (2008) to age because other factors (e.g., type of rater, measure used, and time of assessment) could contribute to these differences. Although the small--but growing--body of research on the psychometric properties of the current ADHD symptoms includes cross-sectional analysis, no longitudinal investigations exist yet.

Adding new symptoms to the DSM

Another important issue to consider is the possibility of supplementing the current ADHD symptoms with new symptoms that are better indicators of ADHD. Several rating scales have been developed that include a number of symptoms beyond the 18 included in the current DSM, and evidence indicates that these symptoms are good indicators of ADHD. For example, “excitable/impulsive” and “cannot remain still” are two hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms from the Conner’s Teacher Rating Scale that have difficulty parameters that span the range of their latent traits (Purpura & Lonigan, 2009). In future revisions of the DSM, additional symptoms should be considered to develop diagnostic categories for ADHD that are as clear and accurate as possible across a wide range of ages.

Scoring techniques

In addition to decisions regarding which symptoms should be included in future revisions of the DSM, decisions regarding proper scoring techniques should also be evaluated. In current clinical practice, symptoms are frequently scored in a dichotomous manner. In contrast, researchers often use polytomously scored symptoms. As found in this study, the total scores within inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity for the two scoring techniques were highly correlated, which means that either scoring method is adequate. Decisions about which scoring method to use should be made based on the purpose of rating behavior.4 If the purpose of rating behavior is to measure the level of a trait, as is often the case in conducting research studies, polytomous scoring is the better method. Polytomous scoring allows for the development of a broad abilities test that can assess behaviors across the spectrum of the latent trait. This continuous behavioral data is useful in research because it enables researchers to relate the total level of a latent trait to other domains (e.g., academic achievement, social functioning). Alternatively, if the purpose of assessing behavior is to diagnose children with ADHD (i.e., differentiate between individuals above and below a specific cutoff) then dichotomous scoring would be the more appropriate method. In dichotomous scoring, endorsement of symptoms should be centered on the theta value that is most indicative of functional impairment. This allows separation of children into groups of those with functional impairment severe enough to warrant diagnosis and those falling within a “normal” range of behavior. To identify an appropriate theta (i.e., impairment cut point), scores on measures such as the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006) can be compared to symptom ratings. The theta value on the behavior rating scales that is indicative of clinical impairment, as indicated by the IRS, would be a reasonable value to utilize as a clinical cut point for diagnosis. Further, this theta value could be converted into a total severity score on the behavioral rating form for ease of clinical diagnosis.

The above rationale for employment of dichotomous scoring for diagnosis assumes that for all symptoms, category choices on the rating scale are equated (e.g., for all symptoms, choosing a “2” indicates the same level of the latent trait). The problem with the current method of dichotomization is that it was developed without support from empirical evidence; therefore, a score of a 2 on one symptom might not indicate the same level of a behavior with respect to the underlying behavioral construct as a score of a 2 on a different symptom. In the traditional dichotomization of ADHD rating scales, scores of 0 and 1 indicate normal behavior and scores of 2 and 3 indicate abnormal behavior. Using the traditional scoring for the data in this study, endorsement of Inattention Symptom 8 required a theta (latent trait) value of 1.13, but endorsement of Inattention Symptom 9 required a theta value of 1.86, which is a difference in the underlying trait of inattention of almost a full standard deviation. In cases such as this, markedly different levels of severity of the underlying latent trait (i.e., inattention) would be assigned the same classification of either “normal” or “abnormal.” When developing a symptom cutoff using dichotomously scored data, all ADHD symptoms should be centered as close as possible on the same latent trait value. For example, a cutoff of 3 on Symptoms 2 and 8 and a cutoff of 1 on Symptom 7 could be used to reduce variability across symptoms. Centering on a latent trait value enhances discrimination between individuals above and below a specified level of latent trait and makes dichotomous scoring a valid way of diagnosing ADHD.

Limitations

The findings from this study provide a foundation upon which future revisions of the DSM can be built; however, two limitations to this study should be addressed. First, children in this study were rated by intervention instructors, not classroom teachers or parents. Ratings from different sources may provide different information and should be examined through differential symptom functioning analyses. Symptoms that exhibit stability across raters, sexes, ethnicities, and ages, and are strong indicators of their latent constructs could be identified and selected for future revisions of the DSM. Second, the sample utilized in these analyses was predominantly African American and thus not racially diverse. Previous research has not found differential symptom functioning in an alternative measure of ADHD-spectrum behaviors (Purpura & Lonigan, 2009); therefore, it is likely that results will remain consistent across racial groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study provide valuable information for the refinement of the ADHD diagnostic symptoms for future revisions of the DSM. Symptoms with inadequate psychometric properties should be removed, and redundant symptoms should be evaluated for removal based on the longitudinal stability of symptom psychometric properties. Further, it may be beneficial to clinicians and researchers to include additional symptoms taken from other diagnostic measures of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity to supplement the current symptoms and provide for diagnostic symptoms that span the developmental continuum of ADHD. This study provides a foundation on which to build the area of psychometric evaluation of diagnostic symptoms in general. This work in refining the ADHD diagnostic symptoms for diagnostic application in a preschool population can easily be expanded to diagnosis of ADHD in all ages, including adults, as well as in refining the diagnostic symptoms for all clinical domains in the DSM. Ultimately, this type of DSM refinement research could result in a stronger and more accurate diagnostic system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD30988) and a grant from the Institute of Education Science, U.S. Department of Education (R305B04074). Views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and have not been reviewed or approved by the granting agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pasX.

Although this study examines the psychometric properties of ADHD symptoms, the traditional IRT terminology of “Item Information Function” is utilized to maintain consistency across studies that utilize this methodology.

Exact SES status by child was not obtained as part of this study. However, 19% of the children attended Head Start centers, which have an income maximum for eligibility. The remaining children were primarily from county-run Title I preschools that served predominantly low to middle income children.

A multi-level IRT model was run in Mplus with the small-group instructor at the cluster level (there were 15 total clusters). The variance accounted for at the cluster level was non-significant (p = .06). Therefore, non-independence of ratings was not a concern for the remaining analyses.

When dichotomous data are obtained from polytomously scored data, the dichotomous difficulty parameters are equal to the difficulty parameter for the point at which the dichomization occurred. For example, in the case of a four-option Likert scale such as the ADHD-IV Rating Scale, when it is dichotomized in the same manner used in this paper, the dichotomous difficulty parameter is equivalent to the b2 difficulty parameter. Different parameters may be obtained as a result of method variance if the scoring were initially completed in a dichotomous manner; however, in most clinical and research settings, the symptoms initially are scored polytomously and then dichotomized.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Balsis S, Gleason MEJ, Woods CM, Oltmanns TF. An item response theory analysis of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria across younger and older age groups. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:171–185. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales – Revised: Long Form. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Heath Systems; 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales – Revised: Short Form. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Heath Systems; 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown RE. Prevalence and correlates of ADHD symptoms in the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2005;9:392–401. doi: 10.1177/1087054705280413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associations Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Erhart M, Döpfner M, Ravens-Sieberer U BELLA study group. Psychometric properties of two ADHD questionnaires: comparing the Conners’ scale and the RBB-HKS in the general population of German children and adolescents—Results of the BELLA study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:106–115. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-1012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Jr, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, et al. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske U, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Pilkonis PA. An application of item response theory to the DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:418–433. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follette WC. Introduction to the special section on the development of theoretically coherent alternatives to the DSM system. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1117–1119. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances A, Mack A, First MB, Jones C. DSM-IV: Issues in development. Psychiatric Annals. 1995;25:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Stallings M, et al. An item response theory analysis of DSM-IV conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:42–50. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R. Item response theory analyses of the parent and teacher ratings of the DSM-IV ADHD Rating Scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:865–885. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Burns GL, Walsh JA. Parent ratings of the oppositional defiant disorder systems: Item response theory analyses of cross-national and cross-racial invariance. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton RK, Swaminathan H, Rogers HJ. Fundamentals of Item Response Theory. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Weisz JR. Diagnostic agreement predicts treatment process and outcomes in youth mental health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:711–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Martin C, Mezzich A, et al. Application of item response theory to quantify substance use disorder severity. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Lee SS, Willcutt E. Instability of the DSM-IV Subtypes of ADHD From Preschool Through Elementary School. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:896–902. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Kipp H, Ehrhardt A, Steve S, et al. Three-year predictive validity of DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4–6 years of age. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2014–2020. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns H, et al. Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:204–214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199602000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. Antisocial behavior: More enduring than changeable? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:393–397. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical theories of mental test scores. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Loughran SB. Agreement and stability of teacher rating scales for assessing ADHD in preschoolers. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2003;30:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.1. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Computer program] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Andrews TA, Eiraldi RB, Doherty BJ, Ikeda MJ, DuPaul GJ, Landau S. Evaluating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using multiple informants: The incremental utility of combining teacher with parent reports. Psychological Assessment. 1998a;10:250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Costigan TE, Leff SS, Eiraldi RB, Landau S. Assessing ADHD across settings: Contributions of behavioral assessment to categorical decision making. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:399–412. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Doherty BJ, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Karustis JL, Eiraldi RB, Anastopoulos AD, DuPaul GJ. The predictive validity of parent and teacher reports of ADHD symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1998b;20:57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Purpura DJ, Lonigan CJ. Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale for preschool children: A revised, brief, age-specific measure. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;38:263–273. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland AS, Lesesne CA, Abramowitz AJ. The epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A public health view. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2002;8:162–170. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff H, Rothbart MK. Attention in early development: Themes and variations. New York: Oxford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Schuckit MA. The development of a research agenda for substance use disorders diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) Addiction. 2006;101:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira EG, Fischel JE. The impact of preschool inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity on social and academic development: a review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:755–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark S. MODFIT: A computer program for model-data fit. University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign; 2001. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]