Abstract

Background and purpose:

Statins (HMG CoA reductase inhibitors) have beneficial effects independent of reducing cholesterol synthesis and this includes their ability to acutely activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). The mechanism by which this occurs is largely unknown and thus we characterized the pathways by which statins activate NOS, including involvement of scavenger receptor-B1 (SR-B1), which is expressed in endothelial cells and maintains cholesterol concentrations.

Experimental approach:

Nitric oxide production was monitored in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) exposed to lovastatin (LOV) or pravastatin (PRA) for 10–20 min, alone or following pre-exposure to the end product of HMG-CoA reductase (mevalonate), G protein inhibitors (pertussis/cholera toxins), phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor (U-73122), or intracellular and extracellular calcium chelators – BAPTA-AM and EGTA (respectively), or a function blocking antibody to SR-B1.

Key results:

Both statins increased NO production in a rapid, dose-dependent and HMG-CoA reductase-independent manner. Inhibiting Gi protein or PLC almost completely blocked statin-induced NO generation. Additionally, removing extracellular calcium inhibited statin-induced NO production. COS-7 cells co-transfected with eNOS and SR-B1 increased NO production when exposed to LOV or high-density lipoprotein (HDL), an agonist of SR-B1. These effects were not observed in COS-7 cells with eNOS alone or co-transfected with bradykinin receptor 2, indicating specificity for SR-B1. Further, pretreatment of BAEC with blocking antibody for SR-B1 blocked NO responses to statins and HDL.

Conclusions and implications:

LOV and PRA acutely activate eNOS through pathways that include the cell surface receptor SR-B1, Gi protein, phosholipase C and entry of extracellular calcium into endothelial cells.

Keywords: lovastatin, pravastatin, nitric oxide, scavenger receptor-B1, endothelial cells, eNOS, phospholipase C, calcium

Introduction

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors – statins – are used to lower cholesterol in patients at risk of coronary artery disease and are currently the most frequently prescribed class of drugs. The ability of statins to reduce morbidity and mortality rates among cardiovascular patients (Group, 1994; Auer et al., 2001; Waters, 2006) involves inhibition of HMG CoA reductase, the enzyme responsible for the production of mevalonate and the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of cholesterol. Statins have been shown to have various beneficial effects on vascular function and cells in both human (Dupuis et al., 1999) and animal studies (Faggiotto and Paoletti, 2000; Koh, 2000) that result from inhibition of HMG CoA reductase. The reduction in the levels of inflammatory cytokines and activity of NADPH oxidase observed with statin treatment can be prevented with mevalonate pretreatment (Inoue et al., 2000).

On the other hand, it has become apparent that statins also have beneficial vascular effects unrelated to their lowering effect on cholesterol (Kaesemeyer et al., 1999; Farmer, 2000; Liao and Laufs, 2005; Waters, 2006). Several animal studies have shown cholesterol-independent vascular effects in which statins protect against stroke and preserve ischaemic-reperfused myocardium (Lefer et al., 1999; Yamada et al., 2000; Di Napoli et al., 2001). Additionally, beneficial clinical effects of statins in acute cardiac conditions have been shown to occur independently of cholesterol lowering (Fonarow, 2002; Poldermans et al., 2003; Wassmann et al., 2003; Ridker et al., 2008).

Previously, our laboratory observed a rapid elevation of NO production (<10 mins) in endothelial cells treated with pravastatin (PRA) or simvastatin, which was inhibited by the NOS inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (Kaesemeyer et al., 1999). Others have also shown that statins can rapidly phosphorylate and activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) via PKA and PI-3K/Akt (protein kinase B) pathways (Kureishi et al., 2000) and that pretreatment with mevalonate does not prevent these events (Harris et al., 2004). Thus, these actions appear not to be dependent on inhibition of HMG CoA reductase.

As the action of statins in producing nitric oxide is very rapid, we reasoned that the mechanism might involve cell surface receptors and elevation of calcium levels necessary for the interaction with calmodulin and subsequent activation of eNOS. The scavenging receptor type-B1 (SR-B1) is expressed in endothelial cells at the caveolae and maintains caveolar cholesterol concentration and eNOS localization (Uittenbogaard et al., 2000). SR-B1 binds to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) leading to trafficking of cholesterol esters from cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis (Peng et al., 2004). HDL has been shown to have beneficial vascular effects in endothelial dysfunction, by promoting cholesterol efflux (Assanasen et al., 2005) thereby reducing the formation of atherosclerosis plaques (Noor et al., 2007). The binding of HDL to SR-B1 also activates eNOS (Yuhanna et al., 2001). However, a link between the acute effects of statins and SR-B1 is not known.

The aim of our study was to determine the mechanisms involved in the acute activation of eNOS induced by statins. We hypothesized that statins rapidly activate NOS through pathways involving the SR-B1 receptor, a G protein coupled receptor, phospholipase C (PLC) activation and enhanced calcium levels for NOS activation, independent of HMG CoA reductase inhibition.

Methods

Bovine aortic endothelial cell (BAEC) cultures

Freshly isolated cultures of BAEC obtained at our institution were maintained and used between passages of 3 and 6 in M199 medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% foetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin (100 U·mL−1) and streptomycin (100 µg·mL−1). Low passage cells were used for experimental purposes in order to minimize the possibility of cell transformation or phenotypic drift that can occur with repeated sub-culturing. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

COS cell culture and transient transfections

COS-7 cells, an African green monkey kidney fibroblast cell line, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing penicillin, streptomycin and 10% FCS. Cells were grown to 90–95% confluency in 12-well plates and subsequently transfected using wild-type (wt) eNOS according to the manufacturer's instructions (LipofectAMINE 2000, Invitrogen). After 24 h the cells were treated using the experimental protocols outlined in the figure legends. In other experiments, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with the cDNA encoding eNOS and either of the endothelial-specific surface receptors: bradykinin receptor 2 (B2) and SR-B1. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were exposed to bradykinin, HDL, lovastatin (LOV) or PRA for 10 or 20 min. These procedures have been described previously (Church and Fulton, 2006).

NO measurement

We used two methods to measure NO – DAF fluorescence which assays NO formation in living cells and chemiluminescence which measures NO production and release in cell conditioned media. DAF-2DA DAF-2DA is the fluorescent dye, 4, 5-diaminofluorescein diacetate; it is a cell-permeable derivative of DAF-2, which is hydrolysed by intracellular esterases to release the NO-sensitive dye DAF-2. NO reacts with DAF-2 to yield bright green fluorescent triazolofluoresceins, which can be quantified using excitation-emission specific for this dye (Ex: 485 & Em: 538 nm). For experimental purposes, cells were plated and grown in 96-well black plates with clear bottoms (Fisher Scientific) for 48 h and then incubated with DPBS containing L-arginine (10−5 M) and HEPES (5 × 10−4 M) for 20–25 min. Cells were exposed to the dye (10−5 M) for another 30 min and then washed with buffer. After the addition of fresh buffer, the cells were treated with statins (10−7–10−5 M) and monitored for changes in fluorescence intensity over a 10 or 20 min period. Readings were taken using a fluorescent plate reader (Polar Star Optima; BMG technologies, Cary, NC, USA). The rise in fluorescence intensity is proportional to the amount of NO formed in the cells (Lampiao et al., 2006) and is prevented by the NOS inhibitor L-NAME. The effects of the different treatments are reported as % increase in fluorescence intensity over control readings during that period.

Chemiluminescence

For this method, cells were incubated in fresh serum-free medium for 20 min and samples were collected for basal reading. Cells were then treated with statins (10−7–10−5 M) for 10 or 20 min and samples collected for treatment reading. In order to measure nitric oxide formation, nitrite (NO2−), the stable breakdown product of NO in aqueous medium was analysed using NO-specific chemiluminescence. Samples containing NO2− were refluxed in glacial acetic acid containing sodium iodide. Under these conditions NO2− was reduced to NO, which was quantified by a chemiluminescence detector after reaction with ozone in a Sievers Nitric Oxide Analyzer (Model 280i, Ionics Instruments, Boulder, CO, USA). The amount of nitric oxide generated was quantified by measuring the difference in NO levels in samples before and after treatment (Fulton et al., 1999).

Treatment with inhibitors

Inhibitors of Gi (pertussis toxin) and Gs (cholera toxin) subunits were used to determine the role of G protein coupled receptors in statin-induced NO release

Upon confluency, BAECs were incubated for 2 h with 2 × 10−4 M pertussis toxin or 10−4 M cholera toxin. Cells were then washed and exposed to statins (10−6 M) for 20 min. NO was detected using chemiluminescence.

Effects of the PLC inhibitor, U-73122 on acute activation of eNOS by statins

Bovine aortic endothelial cells were pretreated with the PLC inhibitor U-73122, 10−5 M, for 60 min and subsequently treated with statins for 10–20 min. NO production was measured using DAF-2DA. U-73122 is a membrane permeable aminosteroid PLC inhibitor that has been shown to inhibit this enzyme in human platelets and neutrophils and have preference for the β isoform (Wang, 1996; Hou et al., 2004).

Effects of intracellular calcium chelation using BAPTA-AM

Bovine aortic endothelial cells were pre-incubated with DPBS containing calcium and the intracellular calcium (Ca2+) chelator BAPTA-AM (2 × 10−5 M) for 30 min. Subsequently DAF-2DA was used to detect NO production in response to statins (10−6 M) treatment for 10–20 min.

Effects of extracellular calcium chelation using calcium-free medium and EGTA

Bovine aortic endothelial cells were washed and pre-incubated with calcium-free DPBS containing the extracellular Ca2+ chelator EGTA (10−4 M) for 30 min and subsequently exposed to statins (10−6 M) for 10–20 min. NO was detected using DAF-2DA.

Effect of an SR-B1 blocking antibody on NO responses to LOV, PRA and HDL

Bovine aortic endothelial cells were pretreated with the SR-B1 blocking antibody (1:200 dilution) (Kielczewski et al., 2009) for 1 h in serum-free media. Samples were taken at −20 min and 0 min (just prior to LOV, PRA or HDL exposure) and +20 min after exposure to statins (10−6 M) or HDL (100 µg·mL−1). NO was detected using chemiluminescence.

Western blot analysis

Bovine aortic endothelial cell or COS-7 cells transfected with the SR-B1 receptor were grown to confluency, lysed and their protein content was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Then 50 µg of protein was loaded per well, separated by electrophoresis using 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then blocked using 5% milk, probed with primary and secondary antibodies and developed by chemiluminescence using ECL reagent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Bands were observed using Gene Snap (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (anova) with the Tukey post test. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. Experiments were performed 4–7 times. Values for each experiment were obtained from 2–4 replicate samples, which were averaged.

Materials

Lovastatin, PRA, DAF-2DA, U-73122, HDL, and cholera and pertussis toxins were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Medium M-199 used for culturing BAECs and Dulbecco's phosphate buffer saline (DPBS), with and without calcium, and DMEM were obtained from Gibco, Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA constructs encoding for eNOS and the B2 have been described elsewhere (Church and Fulton, 2006). Expression clones for the scavenger receptor class B, member 1 (SR-B1) were derived from human aortic cDNA. Antibodies to SR-B1 for blocking receptor function and for protein expression were obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA). BAPTA-AM, EGTA, ionomycin, L-arginine, L-NAME and Na mevalonate were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

NO production in BAECs in response to LOV and PRA

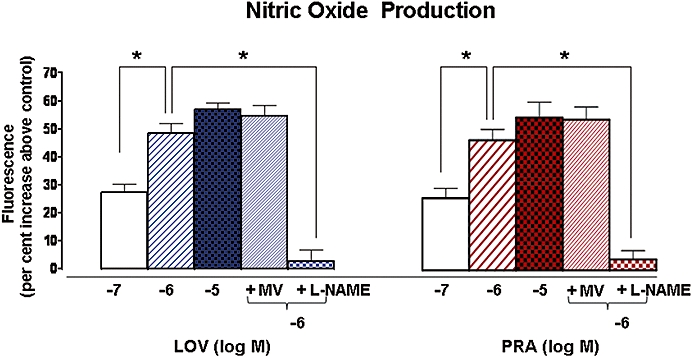

Lovastatin and PRA produced rapid and dose-related increases in endothelial cell NO production (Figure 1). Both statins produced maximum responses at a concentration of 10−6 M. The increases in NO production in response to 10−6 M LOV and PRA were 48 ± 3.4% and 43 ± 4%, respectively, and these actions were completely blocked by pretreatment with L-NAME (10−3 M, 30 min). These data indicate that statins acutely activate eNOS. Pretreatment with mevalonate (5 × 10−4 M, 30 min) did not block activation of NOS by either statin, indicating that their action on NOS is unrelated to HMG-CoA reductase inhibition.

Figure 1.

Effect of L-NAME and mevalonic acid pretreatment on NO produced in response to LOV and PRA. NO production was measured as an increase in DAF-2 fluorescence intensity in BAECs exposed to LOV or PRA (10−7 to 10−5 M) alone for 10 min without (−) or with (+) pretreatment with L-NAME (10−3 M) or mevalonate (5 × 10−4 M) for 30 min. n-values for each group are 5–7. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values between treatment groups with P < 0.05. LOV, lovastatin; NO, nitric oxide; PRA, pravastatin.

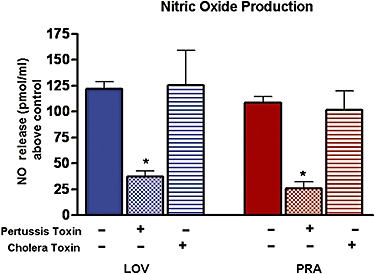

Effects of inhibitors of G protein coupled receptor subunits Gi and Gs, pertussis and cholera toxin, on NO produced in response to LOV and PRA

Our hypothesis is that the rapid NO response to statins involves a cell surface receptor and signalling pathways which quickly activate NOS. In order to investigate the role of G-coupled receptors, BAEC were treated with specific inhibitors of the G protein subunits – pertussis toxin (2 × 10−4 M) for Gi and cholera toxin (10−4 M) for Gs – for 2 h and then exposed to LOV and PRA. NO production in response to LOV and PRA was reduced by 70% and 81%, respectively, by pretreatment with pertussis toxin, while cholera toxin had no effect on LOV-induced NO production (Figure 2). This suggests that the statin-mediated NO production is probably mediated through the Gi but not the Gs subunit.

Figure 2.

Effects of pertussis (PT) or cholera (CT) toxin on NO produced in response to LOV and PRA. BAEC were exposed to the Gi and Gs subunit inhibitors, pertussis toxin (2 × 10−4 M) or cholera toxin (10−4 M), for 2 h prior to addition of LOV or PRA (10−6 M) for 20 min and measurement of NO production by chemiluminescence. Control NO production was 51.8 ± 6.3, 48.7 ± 4.5 and 56.3 ± 7.4 pmol·mL−1, respectively, after pretreatment with buffer control (−), pertussis (+) or cholera toxins (+). n-values for each group are 4–7. *Indicates difference in values between buffer(−) and pretreatment groups (+) with P < 0.05. BAEC, bovine aorta endothelial cells; LOV, lovastatin; NO, nitric oxide; PRA, pravastatin.

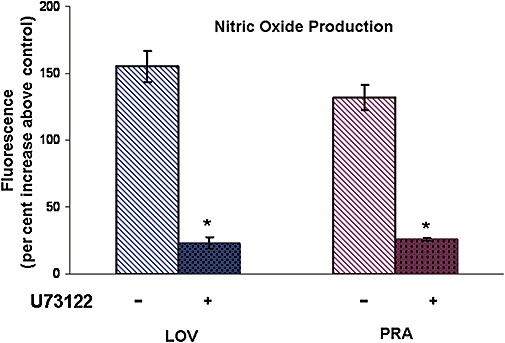

Effects of PLC inhibition on NO produced in response to LOV and PRA

Activation of PLC is known to lead to rapid activation of NOS via elevated levels of intracellular calcium and formation of the Ca2+/calmodulin complex (Sterin-Borda et al., 2002). Pretreatment of BAEC with the PLC inhibitor, U-73122 (10−5 M, 60 min) markedly inhibited the NO produced in response to both statins (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of inhibition of phospholipase C (PLC) on statin-induced NO production. BAEC were pretreated with the PLC inhibitor U-73122 (10−5 M) for 60 min before exposure to LOV or PRA (10−6 M) for 10 min. NO production was measured as an increase in DAF-2 fluorescence intensity. n-values for each group are 4–7. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values between buffer control (−) and pretreatment group (+) with P < 0.05. BAEC, bovine aorta endothelial cells; LOV, lovastatin; NO, nitric oxide; PRA, pravastatin.

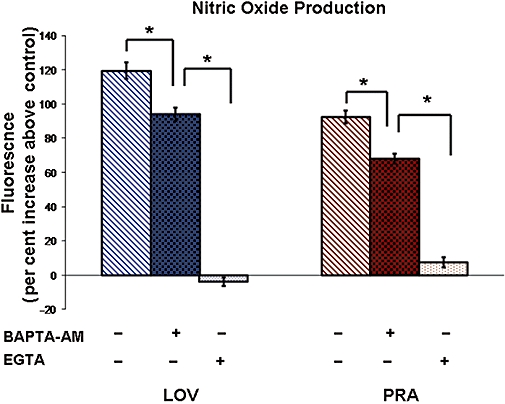

Effects of calcium chelators on NO produced in response to LOV and PRA

BAEC were incubated in calcium-free DPBS containing EGTA (10−4 M, 30 min), then exposed to the statins, and NO production was measured. Removal of extracellular calcium by EGTA blocked statin-induced NO production (Figure 4), indicating the importance of extracellular calcium to this response.

Figure 4.

Effect of intracellular calcium chelation (BAPTA-AM) and extracellular calcium removal and chelation (EGTA) on statin-induced NO production. NO production in BAEC in response to exposure to the statins (10−6 M) for 10 min was measured in the absence (−) and presence (+) of the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM (5 × 10−5 M) or the extracellular calcium chelator EGTA (10−4 M, and medium lacking calcium). NO production was measured as an increase in DAF-2 fluorescence intensity. Cells were exposed to these pretreatments 30 min prior to addition of to statins. n-values for each group are 4–7. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values among buffer control (−) and pretreatment groups (+) with P < 0.05. BAEC, bovine aorta endothelial cells; NO, nitric oxide.

Pretreatment of cells with BAPTA-AM (a chelator of intracellular calcium, 2 × 10−5 M, 30 min) in buffer containing calcium reduced NO production to LOV by 26% and that to PRA by 34% (Figure 4). Thus, intracellular calcium is moderately involved in statin-induced NO production.

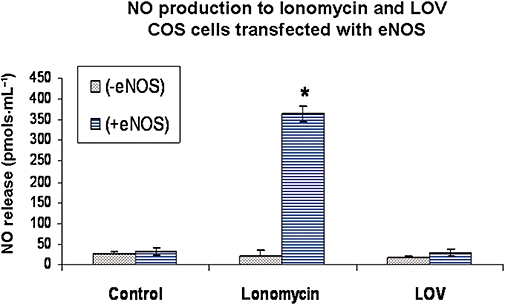

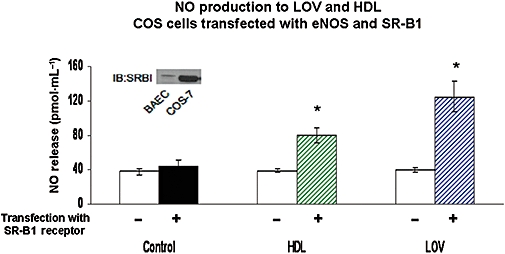

Role of endothelial receptor SR-B1 in LOV-induced NO production in COS Cells

COS-7 cells are an immortalized line of kidney fibroblast cells from the African green monkey that express relatively few surface receptors and are easily transfected to produce recombinant proteins. Figure 5 shows NO production in COS-7 cells transfected with purified wild-type eNOS. When these cells were exposed to a calcium ionophore (ionomycin, 10−6 M), NO production rapidly increased by 9.5-fold (Figure 5). However, LOV (10−6 M) did not cause a significant increase in NO production. HDL (50 µg·mL−1) also did not alter NO production in cells transfected with eNOS alone (Figure 6, – SR-B1). These data suggest that the statin and HDL-induced NO production involve cell surface receptors that are found in endothelial cells.

Figure 5.

Nitric oxide (NO) production in COS-7 cells transfected with wild-type eNOS. NO formation (pmol·mL−1) was measured in COS-7 cells without or with transfection with wild-type eNOS. Transfections were carried out using purified eNOS cDNA for 4–6 h. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were exposed to control saline, ionomycin (10−6 M) or lovastatin (LOV, 10−6 M) for 30 min and NO production measured by chemiluminescence. n-values for each group are 4–6. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values between transfected and non-transfected groups with P < 0.05. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; LOV, lovastatin.

Figure 6.

Effects of addition of SR-B1 to COS cells, transfected with eNOS, on NO produced in response to HDL and LOV. COS cells were transfected with purified cDNA for eNOS (−) alone or also with SR-B1 (+). Transfection of cells was carried out for 4–6 h; after 48 h cells were exposed to HDL (50 µg·mL−1) or LOV (10−6 M) for 20 min and NO production was measured by chemiluminescence. n-values for each group are 4–6. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values between groups with (+) and without (−) transfection with SR-B1 with P < 0.05. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LOV, lovastatin; SR-B1, scavenger receptor-B1.

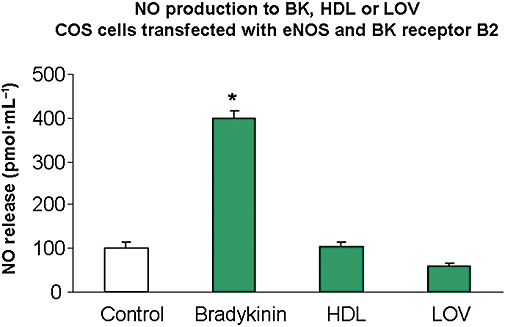

In order to investigate the role of endothelial receptors in statin-induced NO production, COS cells were co-transfected with eNOS and with either of two endothelial receptors – SR-B1 or B2– for 4–6 h and incubated overnight in regular DMEM. Cells were pre-incubated in serum-free medium for 2 h before exposure to LOV (10−6 M) or HDL (50 µg·mL−1) for 30 min.

In cells also transfected with SR-B1, the addition of LOV caused about a threefold increase in NO production compared with control, indicating that statins can interact with SR-B1 to stimulate NO production (Figure 6). HDL, a known agonist of SR-B1, also increased NO production in SR-B1-transfected cells, but to a lesser extent, about twofold (Figure 6). A higher dose of HDL (100 µg·mL−1) did not raise NO production significantly above that observed for the 50 µg·mL−1 dose (not shown).

Western blot analysis of the COS cells transfected with SR-B1 showed prominent expression of this receptor protein, but not in non-transfected COS cells. By comparison, an equal amount of protein from BAECs showed a lesser but definite expression band for SR-B1 (Inset, Figure 6).

In cells transfected with the B2 receptor, the addition of bradykinin (1 µM) caused an approximately fourfold increase in NO production. Addition of either HDL or LOV to these cells containing the B2 receptor did not affect production of NO (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effects of bradykinin (BK) receptor B2 on NO produced in response to HDL and LOV in COS cells. NO production in response to bradykinin (BK), HDL and LOV was measured in cells transfected with both bradykinin receptor 2 (B2) and eNOS. Transfection was carried out using purified cDNA for B2 cDNA (200 ng·mL−1) along with eNOS (500 ng·mL−1) for 4–6 h. Forty-eight hours later, these cells were exposed to saline (control), bradykinin (10−6 M), HDL (50 µg·mL−1) or LOV (10−6 M) for 20 min and NO production was measured by chemiluminescence. n-values for each group are 4–7. Asterisk (*) indicates difference in values between control and treatment groups with P < 0.05. B2, bradykinin receptor 2; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LOV, lovastatin.

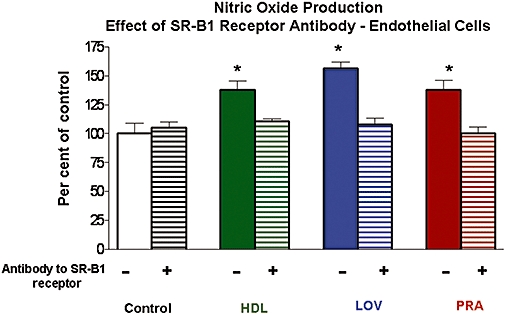

Effect of SR-B1 receptor blockade on NO produced in response to LOV, PRA and HDL in BAEC

To assess whether SR-B1 in endothelial cells mediates the observed statin-induced NO responses, we utilized a function blocking antibody (Ab) specific to SR-B1 (Kielczewski et al., 2009). Pretreatment of BAEC with this SR-B1-Ab prevented the NO response to LOV and to PRA (Figure 8). Additionally, SR-B1-Ab pretreatment blocked NO production in response to HDL (Figure 8). HDL is known to activate endothelial cell NOS via SR-B1 (Yuhanna et al., 2001). Western blot analysis of the BAEC cells showed definite expression of SR-B1 (Inset, Figure 6).

Figure 8.

Effects of blockade of SR-B1 in BAEC on NO produced in response to LOV, PRA and HDL. NO production in response to LOV or PRA (each at 10−6 M) or HDL (100 µg·mL−1) without or with pretreatment with a SR-B1 blocking antibody (1:200 dilution) was measured by chemiluminescence. Control NO production in untreated cells [Control (−)] was 44.7 ± 6.2 pmol·mL−1. Cells were exposed to the blocking antibody for 1 h prior to addition of LOV, PRA or HDL. n-values for each group are 4–7. Asterisk (*) indicates differences in values between control verses LOV, PRA or HDL and SR-B1 blocking antibody treatment groups with P < 0.05. BAEC, bovine aorta endothelial cells; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LOV, lovastatin; PRA, pravastatin; SR-B1, scavenger receptor-B1.

Discussion and conclusions

Our studies showed that treatment of endothelial cells with LOV or PRA rapidly increased NO production. This rise in NO was blocked by L-NAME, a NOS inhibitor, confirming the role of eNOS in acute statin-induced NO production. Pretreatment of the cells with mevalonate did not prevent the activation of NOS by these statins, indicating that inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase is not involved. NO production in response to statins was very rapid and therefore probably dependent on changes in intracellular signalling events. The finding that two statins, LOV and PRA, share these actions indicates that these effects can be attributed to this class of drugs. In addition, these effects occur at concentrations in the therapeutic dose range for humans (Pentikainen et al., 1992; Laufs et al., 1998).

Treatment of cells with pertussis toxin blocked the statin-induced NO production by about 75% indicating that Gi subunits of G protein coupled receptors are prominently involved in this action on endothelial cells. The Gs subunit inhibitor, cholera toxin did not alter statins' action on NO production, suggesting that the effect is specific with regard to receptor activation involving the Gi subunit of the G protein coupled receptor. Additional studies using endothelial cells with specific mutants of Gi subunits are needed to more fully define the interaction of statins with G protein coupled receptors.

The ability of the PLC inhibitor U-73122 to almost completely block NO production in response to the statins indicates that PLC is crucial for this rapid activation of NOS. PLC is a family of isozymes (α, β and δ) that are activated by agonists binding to G-protein coupled receptors and is involved in the elevation of intracellular calcium, which leads to activation of eNOS (Venema et al., 1996). PLC can also be activated by local glycosphingolipid changes in the plasma membrane and requires calcium in nanomolar concentrations (Wilde and Watson, 2001). Activation of PLC leads to its translocation to the plasma membrane resulting in the breakdown of membrane PIP2 to form diacyl glycerol (DAG) and inositol-3-phosphate (IP3) within cells. DAG activates protein kinase C, which in turn can activate L-type Ca2+ channels (Keef et al., 2001). IP3 also causes release of calcium from intracellular/endoplasmic reticulum pools as well as facilitating the entry of extracellular calcium. In order to determine the role of calcium in the rapid effects of the statins on NOS, we used the chelator EGTA and calcium-free buffer to prevent calcium-entry. This treatment resulted in complete blockade of NO production in response to LOV. Thus, entry of extracellular calcium appears crucial to statin-induced NOS activation. Increased cytosolic calcium promotes binding of calcium-activated calmodulin to eNOS and its dissociation from the inhibitory caveolin-1. In addition, extracellular calcium is required in nanomolar concentrations for PLC activation. Thus, it is possible that the absence of extracellular calcium had a dual effect on statin's action on eNOS by both blocking PLC activation and decreasing cytosolic calcium, which would prevent the activation of eNOS. Chelation of intracellular calcium with BAPTA partially blocked statin-induced NOS activation suggesting that intracellular calcium is involved, but is only secondary to the entry of extracellular calcium. These data are consistent with those from a previous study demonstrating that extracellular calcium influx is more important for eNOS activation than intracellular pools (Church and Fulton, 2006).

COS-7 cells expressing only eNOS failed to respond to LOV, yet ionomycin elicited a robust response. This finding suggests that statin-induced NO production is unique for endothelial cells and that endothelial cell surface receptors are required for eNOS activation. When endothelial receptors for bradykinin (B2) or HDL (SR-B1) were co-transfected with eNOS in COS cells, LOV was observed to significantly increase NO production only in cells expressing the SR-B1 receptor. The increase in NO production to LOV was significantly higher than that of the maximum effective dose of the SR-B1 agonist HDL and suggests that LOV has a higher efficacy than HDL in activating eNOS via SR-B1. Addition of maximally effective doses of LOV and HDL did not elicit an additive effect on NO production indicating that similar mechanisms/pathways are involved (data not shown).

Our experiments in COS cells transfected with SR-B1 provide evidence that LOV may be acting via this cell surface receptor. Importantly, these data are corroborated by experiments in BAEC pretreated with a blocking antibody to SR-B1. Our results demonstrate that HDL and the statins LOV and PRA utilize SR-B1 to activate eNOS in endothelial cells. Pretreatment with a blocking antibody to SR-B1 prevented NOS activation by all three agents. SR-B1 is a scavenging receptor that binds HDL and is involved in bi-directional transport of cholesterol esters from HDL into and from cells. In addition to HDL, SR-B1 binds to a broad range of ligands including AcLDL, OxLDL, VLDL, BSA, anionic phospholipids and apoptotic cells (Krieger, 2001). The role of SR-B1 in stimulating nitric oxide production in endothelial cells and its cardioprotective effects are well documented (Yuhanna et al., 2001), as has been the anti-atherosclerotic effects of HDL (Noor et al., 2007). Recently, it has been reported that blockade of SR-B1 results in the progression of atherosclerosis, despite increased levels of HDL (Kitayama et al., 2006), indicating a critical role for the SR-B1 receptor in the actions of HDL. The observed actions of LOV and PRA via SR-B1 suggest that statins may affect cholesterol trafficking and nitric oxide production by a novel means, unrelated to inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. The ability of statins to activate eNOS requires calcium and PLC but may also involve additional signalling events such as AMP kinase and Akt activation (Kureishi et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2006). While our data suggest that SR-B1 is necessary for LOV to activate eNOS, the mechanism by which SR-B1 transduces intracellular signals and the requirement for Gi in this process requires further investigation.

In summary, our data indicate that there is a rapid and direct mechanism of eNOS activation by statins, which is independent of HMG-CoAR inhibition but involves signalling via specific endothelial receptors, namely the SR-B1 receptor. Critical signalling events including the entry of extracellular calcium and activation of PLC also play a major role in eNOS activation by statins. This mechanism of eNOS activation by statins may be important for their therapeutic use in acute (Di Sciascio et al., 2009), as well as chronic cardiovascular conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the participation of Alia Shatanawi and Joi Livingston, and very helpful and insightful comments of Dr Ruth B. Caldwell. This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL 070251 and EY011766 (to R.W.C) and RO1 HL085827 (to J.D.F.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BAECs

bovine aortic endothelial cells

- B2

bradykinin receptor 2

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- LOV

lovastatin

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PRA

pravastatin

- SR-B1

scavenger receptor-B1

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Assanasen C, Mineo C, Seetharam D, Yuhanna IS, Marcel YL, Connelly MA, et al. Cholesterol binding, efflux, and a PDZ-interacting domain of scavenger receptor-BI mediate HDL-initiated signaling. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:969–977. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer J, Berent R, Eber B. Lessons learned from statin trials. Clin Cardiol. 2001;24:277–280. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960240404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church JE, Fulton D. Differences in eNOS activity because of subcellular localization are dictated by phosphorylation state rather than the local calcium environment. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1477–1488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli P, Antonio Taccardi A, Grilli A, Spina R, Felaco M, Barsotti A, et al. Simvastatin reduces reperfusion injury by modulating nitric oxide synthase expression: an ex vivo study in isolated working rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51:283–293. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sciascio G, Patti G, Pasceri V, Gaspardone A, Colonna G, Montinaro A. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Tardif JC, Cernacek P, Theroux P. Cholesterol reduction rapidly improves endothelial function after acute coronary syndromes. The RECIFE (reduction of cholesterol in ischemia and function of the endothelium) trial. Circulation. 1999;99:3227–3233. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.25.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiotto A, Paoletti R. Do pleiotropic effects of statins beyond lipid alterations exist in vivo? What are they and how do they differ between statins? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2000;2:20–25. doi: 10.1007/s11883-000-0091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer JA. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2000;2:208–217. doi: 10.1007/s11883-000-0022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonarow GC. Statin therapy after acute myocardial infarction: are we adequately treating high-risk patients? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2002;4:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11883-002-0032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, et al. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group SSSS. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Blackstone MA, Sood SG, Li C, Goolsby JM, Venema VJ, et al. Acute activation and phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H560–H566. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00214.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C, Kirchner T, Singer M, Matheis M, Argentieri D, Cavender D. In vivo activity of a phospholipase C inhibitor, 1-(6-((17beta-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (U73122), in acute and chronic inflammatory reactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:697–704. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue I, Goto S, Mizotani K, Awata T, Mastunaga T, Kawai S, et al. Lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has an anti-inflammatory effect: reduction of MRNA levels for interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, cyclooxygenase-2, and p22phox by regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in primary endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2000;67:863–876. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaesemeyer WH, Caldwell RB, Huang J, Caldwell RW. Pravastatin sodium activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase independent of its cholesterol-lowering actions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:234–241. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keef KD, Hume JR, Zhong J. Regulation of cardiac and smooth muscle Ca(2+) channels (Ca(V)1.2a,b) by protein kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1743–C1756. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielczewski JL, Jarajapu YP, McFarland EL, Cai J, Afzal A, Calzi SL, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 mediates vascular repair by enhancing nitric oxide generation. Circ Res. 2009;105:897–905. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama K, Nishizawa T, Abe K, Wakabayashi K, Oda T, Inaba T, et al. Blockade of scavenger receptor class B type I raises high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels but exacerbates atherosclerotic lesion formation in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:1629–1638. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.12.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KK. Effects of statins on vascular wall: vasomotor function, inflammation, and plaque stability. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:648–657. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger M. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a multiligand HDL receptor that influences diverse physiologic systems. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:793–797. doi: 10.1172/JCI14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampiao F, Strijdom H, Plessis SS. Direct nitric oxide measurement in human spermatozoa: flow cytometric analysis using the fluorescent probe, diaminofluorescein. Int J Androl. 2006;29:564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2006.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer AM, Campbell B, Shin YK, Scalia R, Hayward R, Lefer DJ. Simvastatin preserves the ischemic-reperfused myocardium in normocholesterolemic rat hearts. Circulation. 1999;100:178–184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao JK, Laufs U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor R, Shuaib U, Wang CX, Todd K, Ghani U, Schwindt B, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol regulates endothelial progenitor cells by increasing eNOS and preventing apoptosis. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Akmentin W, Connelly MA, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Williams DL. Scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) clustered on microvillar extensions suggests that this plasma membrane domain is a way station for cholesterol trafficking between cells and high-density lipoprotein. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:384–396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentikainen PJ, Saraheimo M, Schwartz JI, Amin RD, Schwartz MS, Brunner-Ferber F, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of lovastatin, simvastatin and pravastatin in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;32:136–140. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1992.tb03818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Kertai MD, Krenning B, Westerhout CM, Schinkel AF, et al. Statins are associated with a reduced incidence of perioperative mortality in patients undergoing major noncardiac vascular surgery. Circulation. 2003;107:1848–1851. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066286.15621.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterin-Borda L, Gomez RM, Borda E. Role of nitric oxide/cyclic GMP in myocardial adenosine A1 receptor-inotropic response. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:444–450. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Lee TS, Zhu M, Gu C, Wang Y, Zhu Y, et al. Statins activate AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114:2655–2662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uittenbogaard A, Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, Blair A, Smart EJ. High density lipoprotein prevents oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced inhibition of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase localization and activation in caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11278–11283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema RC, Sayegh HS, Kent JD, Harrison DG. Identification, characterization, and comparison of the calmodulin-binding domains of the endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6435–6440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JP. U-73122, an aminosteroid phospholipase C inhibitor, may also block Ca2+ influx through phospholipase C-independent mechanism in neutrophil activation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1996;353:599–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00167177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann S, Faul A, Hennen B, Scheller B, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Rapid effect of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibition on coronary endothelial function. Circ Res. 2003;93:e98–e103. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099503.13312.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters DD. What the statin trials have taught us. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde JI, Watson SP. Regulation of phospholipase C gamma isoforms in haematopoietic cells: why one, not the other? Cell Signal. 2001;13:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Huang Z, Dalkara T, Endres M, Laufs U, Waeber C, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent cerebral blood flow augmentation by L-arginine after chronic statin treatment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:709–717. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhanna IS, Zhu Y, Cox BE, Hahner LD, Osborne-Lawrence S, Lu P, et al. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. 2001;7:853–857. doi: 10.1038/89986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]