Abstract

Objectives. To determine the influence of disease-related variables on hand cortical bone loss in women with early inflammatory arthritis (IA), and whether hand cortical bone mass predicts subsequent joint damage.

Method. Adults aged ≥16 years with recent onset of IA were recruited to the Norfolk Arthritis Register between 1990 and 1998, and followed prospectively. At baseline, patients had their joints examined for swelling and tenderness and had CRP and disease activity 28-joint assessment score (DAS-28) measured. Radiographs of the hands were performed in a subgroup of patients at Year 1 and at follow-up, which were assessed using digital X-ray radiogrammetry (DXR). They were also evaluated for the presence of erosions using Larsen’s method. Linear mixed models were used to investigate whether disease-related factors predicted change in DXR–areal bone mineral density (BMDa). We also evaluated whether DXR–BMDa predicted the subsequent occurrence of erosive disease.

Results. Two hundred and four women, mean (s.d.) age 55.1 (14.0) years, were included. Median follow-up between radiographs was 4 years. The mean within-subject change in BMDa was 0.024 g/cm2 equivalent to 1% decline per year. After adjustment for age, height and weight, compared with those within the lower tertile for CRP, those in the upper tertile had greater subsequent loss of bone. This was true also for DAS-28 and Larsen score. Among those without erosions on the initial radiograph (121), DXR–BMDa at baseline did not predict the new occurrence of erosions.

Conclusion. Increased disease activity and severity are associated with accelerated bone loss. However, lower BMDa did not predict the new occurrence of erosive disease.

Keywords: Inflammatory arthritis, Digital X-ray radiogrammetry, Norfolk Arthritis Register, Radiological erosions

Introduction

Individuals with inflammatory arthritis (IA) are at increased risk of bone loss and fracture. The level of disease activity is linked with greater bone loss, as measured at the spine, hip or hand using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [1–4].

Radiogrammetry, developed in the 1960s, was based on morphometric measurements of cortical bone width (metacarpal bones) on hand radiographs to provide an estimate of bone mass [5]. The method was widely used and inexpensive; however, with manual use of callipers for the measurement precision was limited [coefficient of variation (CV)% = 8–11%] [6]. Other X-ray-based absorptiometry methods (DXA and QCT) for quantitative assessment of the skeleton subsequently replaced radiogrammetry. However, over the past decade computer vision techniques [active shape/appearance models (ASM/AAM)] have been applied to the measurements [digital X-ray radiogrammetry (DXR) Pronosco A/S, HERLEV, Region Hovedstaden, Denmark] resulting in improved precision (CV = 0.6–1.0%) [7–11]. Areal bone mineral density (BMDa) assessed using DXR has been shown to correlate well with central and peripheral DXA [12].

Hand radiographs are part of routine management of RA and IA, and therefore DXR provides a method for quantifying BMDa in these patients. Data from cross-sectional studies of RA patients suggest that a reduction in DXR–BMDa is associated with markers of disease severity [13–20]. Less is known about the influence of disease activity and functional variables with data from both cross-sectional and prospective studies providing inconsistent results [18, 20–23]. If hand bone loss using DXR is to be considered as an outcome measure or prognostic indicator of IA, it should be associated with measures of disease activity and severity.

We studied women recruited to the Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR), a unique primary care-based cohort of adults with recent onset of IA, in which information about disease activity is recorded in a standardized fashion. The aim of this analysis was to assess the validity of DXR as a research tool in patients with IA by determining the influence of disease-related variables on hand cortical bone loss in early IA. We also examined whether hand cortical bone mass can predict the subsequent development of erosive disease.

Methods

Patients

Patients were recruited from the NOAR, a primary care-based inception cohort of adults aged ≥16 years with early IA based in Norfolk, UK. Patients are included in the register if they have two or more swollen joints for a period of at least 4 weeks, with a symptom onset since 1 January 1990. Detailed methods for the study have been published previously [24]. All aspects of the study were approved by the Norwich Research Ethics Committee. All patients gave written informed consent before entering into the study.

Assessment

At baseline, patients were assessed by a research nurse using a structured questionnaire and completed the British version of the HAQ [25]. The nurse-administered questionnaire covered smoking, previous hormone therapy use and menopausal status. The nurse also examined the joints for swelling, tenderness and deformity. A blood sample was taken for the measurement of CRP and RF. Patients were followed prospectively including assessment at 5 years. Height and weight were measured in a standardized manner at 5 years.

Radiographs

The 1987 ACR classification criteria for RA were applied at the baseline and first-year visits [26]. Radiographs of the hands and feet were performed 1 year after the baseline assessment if patients satisfied the ACR criteria for RA or if the presence of erosions would enable them to satisfy these criteria [26]. Radiographs were performed at Year 5 on all subjects who consented, and then again at Year 10 if erosive change was present on the 5-year radiograph. Radiographs were independently scored by two observers using Larsen’s method [27]. In 2005, hand radiographs from participants who had at least two sets of radiographs were analysed using DXR (Sectra Pronosco X-Posure system; Sectra Imtec AB, Linköping, Sweden). After digitization of the X-ray the narrowest parts of the shafts of the second, third and fourth metacarpals were identified and, for set lengths of these metacarpals (second = 2 cm; third = 1.8 cm and fourth = 1.6 cm), the cortical width, bone width, metacarpal index (MCI) and BMD (BMDa g/cm2) were calculated automatically. Further details have been described previously [11]. The precision (hand analysis only) in this cohort (n = 30) with duplicate digitization and analysis was CV = 0.19% and standardized coefficient of variation (SCV) = 0.35%.

Analysis

The analysis was restricted to women with an onset of symptoms before 2000, an initial radiograph performed within 2 years of the baseline assessment and at least one follow-up radiograph. The relatively small number of men fulfilling these criteria precluded meaningful analysis. Using baseline joint counts, we calculated a (CRP-derived) disease activity 28-joint assessment score (DAS-28) [29]. Linear regression was used to determine the association between DXR and BMDa assessed on the initial radiograph and the various arthritis and non-arthritis-related risk factors assessed at baseline, with DXR–BMDa as the dependent variable and adjustments made for age, height and weight. Results are expressed as β-coefficients (g/cm2) and 95% CI. Linear mixed models were used to determine the impact of baseline arthritis and non-arthritis-related variables on the within-subject change in DXR–BMDa (using serial radiographs) with the results expressed as mean change in DXR–BMDa with time (g/cm2/year). Among patients, who were free from erosions on their initial radiograph, we used logistic regression to determine whether DXR–BMDa predicted the occurrence of new erosions in the subsequent radiographs.

We explored (also using linear regression) whether DXR–BMDa based on assessment of the initial radiograph predicted change in disease-related variables between Years 1 and 5. The changes in disease-related variables were logarithmically transformed if their distribution was skewed. Finally, we used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to examine the correlation between change in DXR–BMDa and change in disease-related factors between Years 1 and 5. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA, 2008).

Results

Subject characteristics

Two hundred and four women, mean (s.d.) age 55.1 (14.0) years, were included in the analysis. Mean height was 1.6 m and weight 69.4 kg; 17.7% were current smokers; 45% were post-menopausal and of these, 13.0% reported taking HRT (Table 1). The median swollen joint count was 8 and tender joint count 8; 37% of patients had a positive RF and 81% satisfied the ACR criteria for RA at baseline (Table 2). With respect to the radiographs at Year 1, the mean (s.d.) Larsen score at Year 1 was 8.8 (11.8) and 39% of patients had radiological erosions.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics

| Variable | n = 204 |

|---|---|

| Age at interview, mean (s.d.), years | 55.1 (14.0) |

| Heighta, mean (s.d.), m | 1.6 (0.1) |

| Weighta, mean (s.d.), kg | 69.4 (13.2) |

| Age at natural menopauseb, mean (s.d.), years | 49.3 (4.5) |

| Post-menopausal, % | 45.1 |

| Current smoker, % | 17.7 |

| Ever taken OCP, % | 43.6 |

| Ever taken HRTb, % | 13.0 |

aHeight and weight were measured at the fifth anniversary visit. bOf the 45.1% women who were post-menopausal.

Table 2.

Disease-related characteristics measured at baseline

| Variable | n = 204 |

|---|---|

| CRP, mean (s.d.), mg/l | 19.7 (38.6) |

| DAS-28, mean (s.d.) | 4.6 (1.3) |

| HAQ score (0–3), mean (s.d.) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Number of swollen joints (0–28), median (IQR) | 8 (4–14) |

| Number of tender joints (0–28), median (IQR) | 8 (3–15) |

| Number of both swollen and tender joints (0–28), median (IQR) | 5 (1–9) |

| RF positive (titre ≥ 1/40), % | 36.9 |

| Satisfied ACR RA criteria (4/7 definition), % | 80.9 |

| Currently taking steroids, % | 8.9 |

DXR–BMDa

One hundred and twenty-two had two films and 82 had three or more. The median time between first and follow-up radiographs was 4 years (interquartile range 3.8–4.4). Mean BMDa on the initial radiograph was 0.527 and 0.499 g/cm2 on the subsequent film. The mean within-subject change in BMDa was −0.024 g/cm2, an ∼1% decline per year.

Determinants of BMDa and change in BMDa

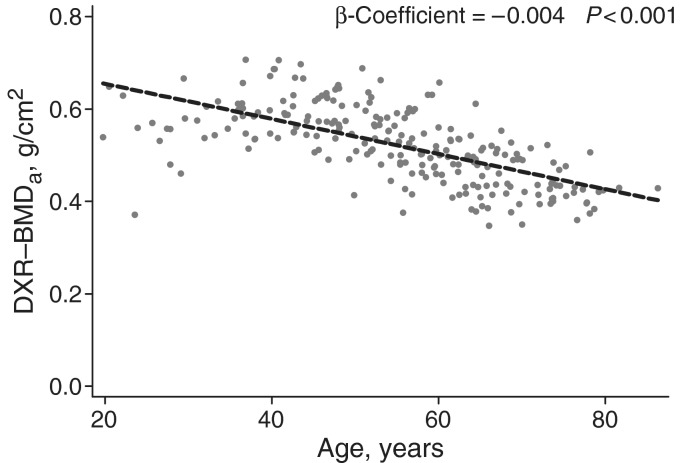

Age at baseline was associated with a lower BMDa at baseline (β-coefficient per 10 years = −0.035; 95% CI −0.041, −0.029), see Fig. 1. Ever use of the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) was significantly associated with higher BMDa (β-coefficient = 0.024; 95% CI 0.004, 0.045) as was HRT use (β-coefficient = 0.020) although the CIs around the parameter estimates embraced unity. Parity and smoking were not linked with BMDa. A higher swollen joint count was associated with lower BMDa (upper vs lower tertile, β-coefficient = −0.028) (Table 3). Individuals satisfying the ACR criteria had a lower BMDa than those who did not (β-coefficient = −0.028; 95% CI −0.050, −0.007). BMDa was lower in those with higher CRP, Larsen score, HAQ score and DAS-28 although the CIs around the parameter estimates embraced unity.

Fig. 1.

DXR–BMDa at Year 1 by age.

Table 3.

Influence of disease-related factors on DXR–BMDa at Year 1 in women

| DXR–BMDa, g/cm2 | |

|---|---|

| β-coefficienta (95% CI) | |

| Swollen joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | −0.022 (−0.042, −0.001)* |

| Upper | −0.028 (−0.047, −0.008)* |

| Tender joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | 0.003 (−0.017, 0.023) |

| Upper | 0.005 (−0.016, 0.026) |

| Both S + T joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | 0.006 (−0.014, 0.026) |

| Upper | −0.010 (−0.031, 0.011) |

| CRP tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | −0.003 (−0.028, 0.022) |

| Upper | −0.008 (−0.032, 0.017) |

| DAS-28 | |

| <3.2 | Referent |

| 3.2–5.1 | −0.007 (−0.038, 0.024) |

| >5.1 | −0.004 (−0.037, 0.028) |

| HAQ score tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | −0.018 (−0.039, 0.002) |

| Upper | −0.010 (−0.030, 0.010) |

| Larsen score at Year 1 tertiles | |

| Lower | Referent |

| Mid | −0.012 (−0.033, 0.010) |

| Upper | −0.018 (−0.038, 0.002) |

| Erosions at Year 1 (yes vs no) | −0.017 (−0.034, 0.001) |

| RF positive (yes vs no) | −0.004 (−0.024, 0.015) |

| Satisfy ACR criteria (yes vs no) | −0.028 (−0.050, −0.007)* |

| Current steroid use (yes vs no) | −0.006 (−0.037, 0.026) |

aAdjusted for age, height and weight. *P < 0.05. S + T: swollen and tender.

Those in the highest tertile of CRP had a greater rate of subsequent bone loss than those in the lowest tertile group (−0.007 vs −0.003 g/cm2/year) (Table 4). This was true also for DAS-28 (−0.005 vs −0.001 g/cm2/year) and Larsen score (−0.007 vs −0.004 g/cm2/year). None of the other arthritis-related variables predicted accelerated bone loss.

Table 4.

Influence of disease-related factors on change in DXR–BMDa in women

| Mean changea (95% CI) in DXR–BMDa, g/cm2/year | |

|---|---|

| Swollen joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| Mid | −0.006 (−0.008, −0.004) |

| Upper | −0.004 (−0.006, −0.002) |

| Tender joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.006 (−0.008, −0.004) |

| Mid | −0.004 (−0.006, −0.003) |

| Upper | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| Both S + T joint count tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| Mid | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| Upper | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003) |

| CRP tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.003 (−0.005, −0.001) |

| Mid | −0.004 (−0.007, −0.002) |

| Upper | −0.007 (−0.010, −0.005)* |

| DAS-28 | |

| <3.2 | Ref: −0.001 (−0.004, 0.004) |

| 3.2–5.1 | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003)* |

| >5.1 | −0.005 (−0.008, −0.003)* |

| HAQ score tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.004 (−0.006, −0.003) |

| Mid | −0.004 (−0.006, −0.002) |

| Upper | −0.007 (−0.008, −0.005) |

| Larsen score at Year 1 tertiles | |

| Lower | Ref: −0.004 (−0.006, −0.002) |

| Mid | −0.003 (−0.005, −0.001) |

| Upper | −0.007 (−0.009, −0.005)* |

| Erosions at Year 1 | |

| No | Ref: −0.004 (−0.006, −0.003) |

| Yes | −0.006 (−0.007, −0.004) |

| RF positive | |

| No | Ref: −0.004 (−0.006, −0.003) |

| Yes | −0.006 (−0.008, −0.004) |

| Satisfy ACR criteria | |

| No | Ref: −0.004 (−0.007, −0.001) |

| Yes | −0.005 (−0.006, −0.004) |

| Current steroid use | |

| No | Ref: −0.005 (−0.006, −0.004) |

| Yes | −0.006 (−0.010, −0.002) |

aAdjusted for age, height and weight. *P < 0.05 compared with referent category. S + T: swollen and tender.

We then examined whether change in disease-related variables between Years 1 and 5 was associated with baseline DXR–BMDa and also change in DXR–BMDa between Years 1 and 5. Change in disease-related variables was not associated with either baseline DXR–BMDa or change in DXR–BMDa between Years 1 and 5. Change in DXR–BMDa was similar in those taking steroids at Year 1 and/or Year 5 compared with those not taking steroids at either time point.

DXR–BMDa and joint damage

Among those without erosions on the initial radiograph (n = 121), after adjusting for age at onset, height and weight, DXR–BMDa did not predict the development of erosions (odds ratio/per s.d. change in DXR–BMDa = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.4,1.2). Mean (s.d.) Larsen score was 8.8 (11.8) on the first radiograph and 19.2 (22.2) at follow-up. DXR–BMDa at baseline (expressed as a Z-score, with adjustments for age at onset, height, weight and baseline Larsen score) did not predict a change in Larsen score (after log transformation) during follow-up (β-coefficient = −0.18; 95% CI = −0.46, 0.1).

Discussion

In this population-based inception cohort of women with IA, BMDa assessed by DXR declined by 1% per year. Measures of disease activity including CRP and DAS-28, and disease severity predicted subsequent cortical bone loss in the hand. However, bone mass did not predict the development of erosive disease.

Our study used standard methods of clinical assessment. The patients were deliberately selected to include all cases of IA and not just those with RA. Indeed, we have shown that assigning criteria for RA is unstable in this setting during the first 5 years of disease [24]. Clinical assessment of disease activity is subject to measurement error; in an attempt to minimize this, all of the assessments were undertaken by trained research nurses, and formal assessment of inter- and intra-observer variation in assessment of joint counts was good. Any misclassification related to measurement error would tend to reduce the likelihood of finding significant associations. The hand radiographs were assessed on the same radiogrammetry device and precision was good (standardized CV 0.35%). The procedure for taking hand radiographs was, however, not standardized. It is possible that differences between machines used may have contributed to some imprecision; however, the effect of any such imprecision would be to tend to reduce the chance of finding significant associations. Subjects who had undergone hand radiographs had more severe disease as determined by higher joint counts and CRP. Such selection factors are, however, unlikely to have influenced the strength of the observed biological associations, which are based on an internal comparison of those who contributed data. DXR provides an estimate of cortical bone, which is less metabolically active than trabecular bone, and therefore potentially less responsive to change or metabolic effects. Bone loss using radiogrammetry has, however, been shown to be associated with clinically relevant outcomes, including fracture, in patients with RA and elderly women [13, 30]. Finally, our data were related to a cohort of Caucasian women living in the Norfolk (UK) area and so may not be applicable beyond this group.

Quantitative measurements by DXR from hand radiographs have been proposed as outcome measures and prognostic indicators of disease course in RA [17, 18, 22]. However, there are few data from prospective studies that examine the influence of disease-related factors, including disease activity and function on subsequent bone loss assessed using DXR. If bone loss is to be a valid outcome measure in IA, it should reflect changes in both disease severity and disease activity. Data from cross-sectional studies suggest an association between DXR–BMDa and markers of disease severity including Larsen score [13–15, 17–19], Sharp scores [15, 20] and Steinbrocker scores [14, 15, 17]. Jensen (2004) in a 2-year prospective study reported accelerated bone loss in patients with erosive disease [21], whereas Guler-Yuksel (2009) reported no link with erosive disease at baseline, but change in erosive status from baseline to 1 year did predict subsequent bone loss [23]. Our data are broadly consistent with these findings.

In relation to disease activity, data from prospective studies provide discrepant results: with disease activity as assessed using DAS-28 linked with bone loss in one, but not another, study [22, 23]. Our data, which are based on a cohort of patients with relatively early disease confirm that active disease assessed using the DAS-28 and CRP is associated with accelerated bone loss. Change in disease activity was not correlated with change in DXR–BMDa suggesting that radiogrammetry is not a marker of persistent disease activity. As with disease activity there are few prospective data examining the impact of function and the data are conflicting [22,23].

As expected, DXR–BMDa decreased with age. DXR–BMDa was associated with increased past use of OCP and HRT, though the latter failed to attain statistical significance, probably due to small numbers.

In a small pilot study of 24 RA patients, change in DXR–BMDa between baseline and Year 1 predicted erosive disease at 4 years [31]. In a larger study, based on the European Research on Incapacitating Disease and Social Support (EURIDISS) cohort, bone loss in the first year was associated with progressive joint damage assessed by the Sharp score at 5 and 10 years [32]. In contrast to these observations, our study suggests that bone mass assessed at a single time point is unrelated to progressive joint damage. It may be that serial radiographs are required to provide an estimation of change in bone mass to predict worsening joint damage, and measurement at a single time point is not predictive of joint damage. Alternatively, differences in the study design/populations sampled may partly explain these negative findings. We also found no evidence that bone mass as assessed by DXR–BMDa assessed at a single time point was associated with the subsequent increase in disease activity or impaired function suggesting that it is not a marker of disease evolution.

In conclusion, DXR–BMDa is a simple, sensitive and precise method of detecting change in hand cortical bone mass in women with early IA. Increased disease activity and severity are associated with accelerated bone loss, supporting the role of DXR as a research tool, not only in new studies but also retrospectively as hand radiographs are an integral part of disease management in patients with IA.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants and general practitioners in NOAR. NOAR is supported by funding from Arthritis Research UK.

Funding: Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Arthritis Research UK.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gough AK, Lilley J, Eyre S, Holder RL, Emery P. Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1994;344:23–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devlin J, Lilley J, Gough A, et al. Clinical associations of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurement of hand bone mass in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1256–6218. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.12.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forslind K, Keller C, Svensson B, Hafstrom I. Reduced bone mineral density in early rheumatoid arthritis is associated with radiological joint damage at baseline and after 2 years in women. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2590–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deodhar AA, Brabyn J, Pande I, Scott DL, Woolf AD. Hand bone densitometry in rheumatoid arthritis, a five year longitudinal study: an outcome measure and a prognostic marker. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:767–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.8.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett E, Nordin B. The radiological diagnosis of osteoporosis: a new approach. Clin Radiol. 1960;11:166–74. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(60)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams P, Davies G, Sweetnam P. Observer error and measurements of the metacarpal. Br J Radiol. 1969;42:192–7. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-42-495-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies RH, Twining CJ, Cootes TF, Waterton JC, Taylor CJ. A minimum description length approach to statistical shape modeling. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21:525–37. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.1009388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen JT, Andersen PB, Rosholm A, Bjarnason NH. Digital X-ray radiogrammetry: a new appendicular bone densitometric method with high precision. Clin Physiol. 2000;20:330–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2000.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosholm A, Hyldstrup L, Backsgaard L, Grunkin M, Thodberg HH. Estimation of bone mineral density by digital X-ray radiogrammetry: theoretical background and clinical testing. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:961–9. doi: 10.1007/s001980170026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen SP. The metacarpal index revisited: a brief overview. J Clin Densitom. 2001;4:199–207. doi: 10.1385/jcd:4:3:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward KA, Cotton J, Adams JE. A technical and clinical evaluation of digital X-ray radiogrammetry. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:389–95. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyldstrup L, Nielsen SP. Metacarpal index by digital X-ray radiogrammetry: normative reference values and comparison with dual X-ray absorptiometry. J Clin Densitom. 2001;4:299–306. doi: 10.1385/jcd:4:4:299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haugeberg G, Lodder MC, Lems WF, et al. Hand cortical bone mass and its associations with radiographic joint damage and fractures in 50–70 year old female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: cross sectional Oslo-Truro-Amsterdam (OSTRA) collaborative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1331–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.015065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottcher J, Malich A, Pfeil A, et al. Potential clinical relevance of digital radiogrammetry for quantification of periarticular bone demineralization in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis depending on severity and compared with DXA. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:631–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottcher J, Pfeil A, Rosholm A, et al. Digital X-ray radiogrammetry combined with semiautomated analysis of joint space widths as a new diagnostic approach in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3850–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottcher J, Pfeil A, Heinrich B, et al. Digital radiogrammetry as a new diagnostic tool for estimation of disease-related osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis compared with pQCT. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:457–64. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0560-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bottcher J, Pfeil A, Mentzel H, et al. Peripheral bone status in rheumatoid arthritis evaluated by digital X-ray radiogrammetry and compared with multisite quantitative ultrasound. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottcher J, Pfeil A, Rosholm A, et al. Computerized quantification of joint space narrowing and periarticular demineralization in patients with rheumatoid arthritis based on digital x-ray radiogrammetry. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:36–44. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000191594.76235.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen T, Hansen M, Jensen KE, Podenphant J, Hansen TM, Hyldstrup L. Comparison of dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), digital X-ray radiogrammetry (DXR), and conventional radiographs in the evaluation of osteoporosis and bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:27–33. doi: 10.1080/03009740510017986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jawaid WB, Crosbie D, Shotton J, Reid DM, Stewart A. Use of digital x ray radiogrammetry in the assessment of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:459–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.039792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen T, Klarlund M, Hansen M, et al. Bone loss in unclassified polyarthritis and early rheumatoid arthritis is better detected by digital x ray radiogrammetry than dual x ray absorptiometry: relationship with disease activity and radiographic outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:15–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.013888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff M, Haugeberg G, Kvien TK. Hand bone loss as an outcome measure in established rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year observational study comparing cortical and total bone loss. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R81. doi: 10.1186/ar2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guler-Yuksel M, Allaart CF, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, et al. Changes in hand and generalised bone mineral density in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:330–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.086348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Symmons DP, Silman AJ. The Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S94–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirwan JR, Reeback JS. Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified to assess disability in British patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1986;25:206–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/25.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen A, Dale K, Eek M. Radiographic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis and related conditions by standard reference films. Acta Radiol Diagn. 1977;18:481–91. doi: 10.1177/028418517701800415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glüer CC, Blake G, Lu Y, Blunt BA, Jergas M, Genant HK. Accurate assessment of precision errors: how to measure the reproducibility of bone densitometry techniques. Osteoporos Int. 1995;5:262–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01774016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells G, Becker JC, Teng J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint disease activity score (DAS28) and European league against rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:954–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouxsein ML, Palermo L, Yeung C, Black DM. Digital X-ray radiogrammetry predicts hip, wrist and vertebral fracture risk in elderly women: a prospective analysis from the study of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:358–65. doi: 10.1007/s001980200040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart A, Mackenzie LM, Black AJ, Reid DM. Predicting erosive disease in rheumatoid arthritis. A longitudinal study of changes in bone density using digital X-ray radiogrammetry: a pilot study. Rheumatology. 2004;43:1561–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoff M, Haugeberg G, Odegard S, et al. Cortical hand bone loss after 1 year in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts radiographic hand joint damage at 5-year and 10-year follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:324–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]