Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether the geographic density of alcohol retailers was greater in geographic areas with higher levels of demographic characteristics that predict health disparities.

Methods. We obtained the locations of all alcohol retailers in the continental United States and created a map depicting alcohol retail outlet density at the US Census tract level. US Census data provided tract-level measures of poverty, education, crowding, and race/ethnicity. We used multiple linear regression to assess relationships between these variables and retail alcohol density.

Results. In urban areas, retail alcohol density had significant nonlinear relationships with Black race, Latino ethnicity, poverty, and education, with slopes increasing substantially throughout the highest quartile for each predictor. In high-proportion Latino communities, retail alcohol density was twice as high as the median density. Retail alcohol density had little or no relationship with the demographic factors of interest in suburban, large town, or rural census tracts.

Conclusions. Greater density of alcohol retailers was associated with higher levels of poverty and with higher proportions of Blacks and Latinos in urban census tracts. These disparities could contribute to higher morbidity in these geographic areas.

The geographic density of alcohol retailers is a community risk factor that may influence behavior. Alcohol access within a neighborhood may constitute a social influence as drinking behavior is observed and social norms are created in that neighborhood; there may be an accessibility effect resulting from convenience of and proximity to opportunities to purchase alcohol; there may be increased advertising within neighborhoods that have more alcohol retail outlets1; or the alcohol point of sale may have an influence on the neighborhood itself, changing the characteristics of the neighborhood.

To date, previous work researching the impact of retail alcohol density has mainly focused on regional or local assessments, except for a study that examined urban centers at the zip code level.2 The methodologies of the regional studies have also varied, with assessments at a variety of geographic levels: counties,3 cities,4–6 zip codes,7,8 block groups,9 and census tracts.10–14 Such area-level variation may make interpretation or generalizing difficult because individuals' activities often cross administrative boundaries. There have been no national studies on retail alcohol density in nonurban settings; previous nonurban analyses were embedded within regional or state assessments. In addition, it is not known whether potentially important findings regarding the effects of alcohol availability can be applied to locales that have not been directly studied.

To better understand the association between retail alcohol density and demographic predictors of health disparities, we created a continuous density map of alcohol retailers across the continental United States, and we assessed how these points of sale related to demographic characteristics at the census tract level.

METHODS

Points of alcohol sale were for all establishments that the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) identified as selling alcohol in the continental United States. Among these establishments, we designated liquor stores, taverns and bars, grocery stores, gas stations, and convenience stores as potential points of sale. We did not include restaurants as points of sale because we felt that restaurants were less likely to be a primary point of sale for individuals seeking alcohol. This approach is supported by the work of Gruenewald, who found a positive association between alcohol retail outlet density and violence, but only for bars and taverns.15

We then reviewed alcohol sale laws for continental US municipalities and counties by querying each state (via publicly available Internet information or by telephone call) in October 2007 to determine legal points of sale in each municipality and county (e.g., grocery stores, gas stations, and convenience stores). We adjusted our designation of retail alcohol establishments accordingly, such that a given type of store was assumed to sell alcohol if it were legally allowed to do so. The data supplier (Dun & Bradstreet, Short Hills, NJ) geocoded each alcohol retail establishment to its exact address, and we used a geographic information system (ArcGIS 9.3, ESRI, Redlands, CA) for subsequent analysis.

Retail Alcohol Density at the Census Tract Level

We used the geographic coordinates of alcohol retail establishments to develop a census tract–level measure of retail alcohol outlet density. Because census tracts do not necessarily correspond to boundaries that affect alcohol purchasing patterns, census tracts may be an inaccurate unit of geography when describing utilization of alcohol outlets. For example, residents on the periphery of one census tract may in fact obtain alcohol in an adjoining tract; thus, the location of retail outlets outside a census tract could affect the alcohol-seeking behavior of residents within that census tract.

We used kernel density estimation methods with an adaptive bandwidth to create a density surface of retail alcohol availability. We used the LandScan background population dataset provided by Oak Ridge National Laboratory to generate the surface, using an 841 m2 resolution.16 These cells formed the basis for the overall density estimation, providing a fine level of detail and variability (total number of cells = 18 609 356). We then computed a retail alcohol outlet density that accounted for the underlying population of each cell by expanding the bandwidth until 3 points of alcohol sale were included in the analysis area. This bandwidth was then applied to create the kernel used in the probability distribution for the density approximation. For areas of the country that are sparsely populated, we restricted the bandwidth to 25 km to prevent it from expanding to a spatially unreliable distance. The unit of density in this model is alcohol retail outlets per person, which we then scaled to outlets per 1000 people.

Average density within each census tract was calculated on the basis of the densities of the LandScan cells contained within the tract. For cells bisected by a census tract border, we used the proportion of the cell in the census tract and its associated density to compute the overall average for the tract. This average offers a better assessment of access to alcohol for all residents of the census tract, because the alcohol density determination for the cells at the periphery of the census tract (cells that contribute to the average) considers the possibility of purchase in the adjacent census tract. This variable—the average alcohol retail outlet density per 1000 persons within a given census tract—served as the dependent variable.

Tract-Level Demographic Predictors of Health Disparities

We focused on the following health disparity predictors in each census tract: race/ethnicity, poverty, education, and urban crowding. Census information was extracted from summary files 1 and 3 from the 2000 US Census for all census tracts in the continental United States.17,18 The independent measures included percentage of the population that was Black or Latino, percentage of families in poverty, percentage of adults with less than a high school education, median number of rooms per housing unit, and median number of people per household.

Statistical Analyses

Median and interquartile ranges were used as summary indicators, because many variables were skewed toward zero. The dependent variable, retail alcohol density per 1000 population, was log-transformed to reduce skewness. Using the full data set of all census tracts within the continental United States (census tract N = 65 321), we plotted 2-way associations. We log-transformed the following variables to make their relation with the dependent variable more linear: percentage Black, percentage Latino, percentage of families in poverty, and percentage of adults in the tract who attained less than a high school education. This allowed for illustration of nonlinear associations at the upper 25% of the distributions for these health disparity indicator variables.

We used criteria based on the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification system to classify census tracts as urban or rural.19 The RUCA system considers commuting patterns in larger metropolitan or town areas when designating categories. We explored the crude relation between the dependent and independent variables by RUCA categorization to determine whether relationships held for urban as well as nonurban areas, on the basis of a 4-level categorization (urban, suburban, large town, small town/rural).20 We ultimately used a dichotomous categorization of urban versus nonurban to reflect differences found in associations for urban census tracts versus those for nonurban census tracts.

All variables were examined to determine bivariate relationships with the dependent variable. We conducted multiple linear regression with a Bonferroni adjustment to identify independent relationships between alcohol density and the hypothesized measures of health disparity.

RESULTS

Of the approximately 65 000 census tracts in the United States, about 45 000 are considered urban under a 2-tiered RUCA classification scheme. In 2000, urban census tracts had a higher proportion of minority residents, less poverty, higher education, and much higher retail alcohol outlet density (median = 7.4 outlets per 1000 people, compared with 4.8 outlets per 1000 people overall) than did nonurban census tracts. Measures of family and crowding were similar, but because of the large sample size, all P values for the comparisons were statistically significant (P < .05; data not shown).

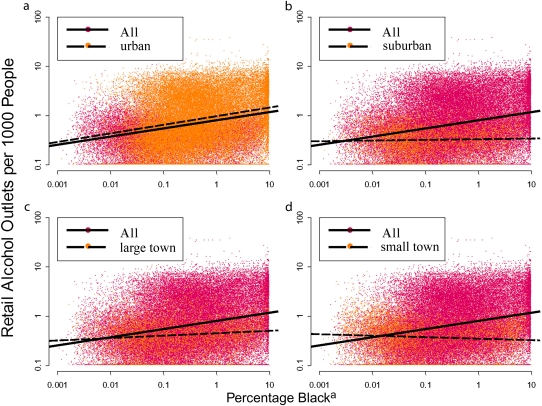

The 2-way plots stratified under the 4-tiered RUCA system indicated that the relationships between retail alcohol density and the independent variables of interest were different for urban census tracts than for suburban, large town, and small town/rural census tracts. There were substantial and significant associations between disparity indicators and retail alcohol density within urban census tracts and little or no relationship among census tracts that were less urban. Figure 1 demonstrates how the association between the density of alcohol outlets per person and the proportion of residents of Black race within each census tract varied by RUCA category.20 For each graph, data for each of the subgroup and its regression line (illustrated by a dotted line) are superimposed on data for the entire sample and its regression line (illustrated by a solid line).

FIGURE 1.

Relationship between percentage of Black population and number of alcohol retailers per 1000 population in (a) urban (n = 44 883), (b) suburban (n = 6385), (c) large town (n = 6536), and (d) small town/rural (n = 7537) areas: US Census tracts, continental United States, 2000.

Note. Census tracts are categorized according to the 4-tiered Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification system.19 Each dotted line indicates the regression line for that graph's RUCA category. The background points and solid lines represent the national sample and are repeated for all graphs, for purposes of visual comparison. Percentage of Black population is log scaled to account for outliers in the model. A 1-point increase in the x-axis represents an increase of 10 percentage points.

Because of the large sample size, all slope differences were statistically significant (P < .001), and all were significantly different from zero. However, the regression lines clearly show that an important positive relationship exists within the urban census tracts. The association with urban census tracts drives the overall relationship, as the regression slopes for all other categories are close to zero. Given the strength of the relationship within the urban census tracts, we focused the remaining analyses on urban tracts only.

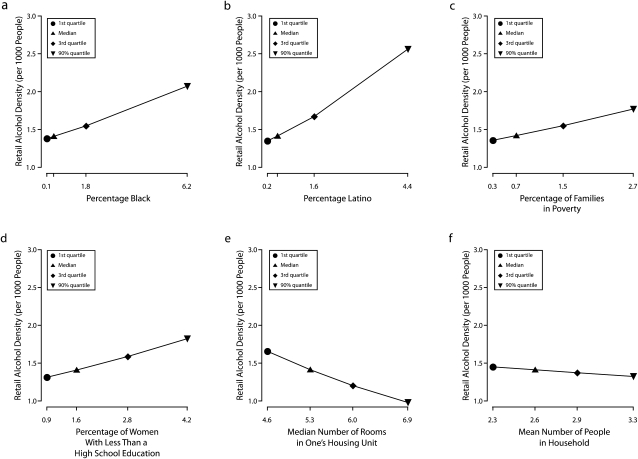

Figure 2 illustrates the independent relationship between census tract–level predictors of health disparities and retail alcohol density in urban census tracts. All relationships were statistically significant (P < .001). There were important positive relationships between retail alcohol density and higher proportions of residents of Black race and Latino ethnicity, higher proportions of families living below the federal poverty level, and higher proportions of women with less than a high school education. For these variables, the relation was nonlinear, with the slope of the association increasing as the health disparity indicator became larger.

FIGURE 2.

Independent associations between retail alcohol density per 1000 population and (a) percentage of Black population, (b) percentage of Latino population, (c) percentage of families in poverty, (d) percentage of women with less than a high school education, (e) median number of rooms in one's housing unit, and (f) average number of people in the household: US Census urban tracts, continental United States, 2000.

Note. Graphs demonstrate where median, interquartile range, and 90th percentile would lie on the regression line. For example, for percentage of Black population, the 90th percentile is 62%, and the third quartile for percentage families in poverty is 15%. The curves are based on a multivariate regression with residual standard error: 0.986 on 42 842 degrees of freedom, adjusted R2 = 0.2668, and F statistic = 2599 on 6 and 42 842 degrees of freedom, with 2034 observations deleted because of missing values. Variables were scaled to make relationships linear. A 1-point increase in the x-axis represents an increase of 10 percentage points.

The nonlinear increase was especially evident in the highest quartile for each measure (the area of interest for health disparities research). The largest association was for percentage of Latino population: all else being equal, retail alcohol outlet density was twice as high as the median in communities at the 90th percentile for proportion of Latino residents (median = 1.3; 90th percentile = 2.6 per 1000 persons). With regard to crowding within a household, as the number of rooms in a housing unit increased (a proxy for less crowding in a household), retail alcohol outlet density decreased. By contrast, there was a small decrease in retail alcohol outlet density as the number of residents in a household increased.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed 2 previous findings, but on the national level. First, retail alcohol density is associated with poverty, education, and race/ethnicity at the census tract level in urban areas throughout the continental United States, providing strong evidence that this is not a regional finding. Higher proportions of residents of Black race and Latino ethnicity, higher proportions of families living in poverty, and overall lower education attainment among neighborhood residents all predict higher density of alcohol retail outlets per 1000 population. Importantly, the relationships were nonlinear, with larger increases in alcohol retail density as the health disparity risk factor became more pronounced. This was especially true for communities above the 75th percentile with respect to race/ethnicity, poverty, and education. We suggest that this type of nonlinear relationship points to a more consequential health disparity than a linear one, and future research should draw attention to such nonlinearity when assessing health disparities.

The second important finding is that these relationships were weak in nonurban census tracts. Although we are unable to establish a causal link, this finding suggests, in agreement with earlier work,21 that increased demand for alcohol among the poor may not be what prompts retail alcohol density increases in poor urban areas; if demand were the driver of supply of alcohol retailers, urban census tracts and nonurban census tracts with similar demographic profiles would show similar increases in alcohol outlet density. This discrepancy may be caused by corporate alcohol interests finding nonurban areas to be less important than urban areas; the economics of retailing being different in nonurban areas; or zoning laws for mixed commercial/residential use varying by locale. Another key finding in this study is how greatly the findings of a geographic analysis can vary by RUCA category.

Others have studied the effect of retail alcohol density, but to our knowledge this is the first work to create a nationally representative, smoothed, continuous surface of retail alcohol exposure at a fine resolution. This model was applied to aggregate data at the census tract level in 2 distinct steps: (1) creating a national density map of retail alcohol exposure independent of administrative boundaries that may be applied to data of any scale, and (2) applying this map to the specific scale of census tracts to assess relationships between alcohol exposure and predictors of health disparities. This process could be repeated with relative ease at another aggregate level; rescaling geographic analysis at the aggregate level is necessary to understand potential impacts of the modifiable area unit problem, in which units of varying sizes or shapes may lead to variation in results.22

This work builds on regional findings. Romely et al. found that Blacks in urban zip codes faced a higher density of liquor stores than did Whites in urban zip codes, but this study did not consider more rural communities.2 Our findings were similar but at a different aggregate level and considered other important routes of exposure, including grocery stores, convenience stores, and gas stations. Others have examined alcohol exposure in urban environments but did not consider exposure at the national level.12,23 The findings from all of these studies point to the importance of considering the alcohol environment in studies of alcohol use and alcohol-related health outcomes.

We suggest that retail alcohol density should be considered as a risk factor in studies of individual risk among urban samples. This national-level dataset on retail alcohol density can readily be linked to other datasets containing alcohol drinking behavior and participant address information to determine neighborhood alcohol risk. Thus, the availability of these data should reduce barriers to considering this risk factor in future research.

There are limitations to this study. Although our analysis was at the detailed level of the census tract, it is possible that these relationships may vary on the basis of different administrative boundaries, such as county or city limits. We did not consider restaurants as a potential form of exposure because of limitations on data accessibility and variation in possession of a liquor license at the local level. It is also possible that the NAICS data misclassified some establishments and that we may have counted establishments as retailers when they in fact were not (i.e., some gas stations and convenience stores may not have sold alcohol even though they legally could have). Finally, it is possible that migration patterns may limit the future utility of our estimates of minority populations and poverty in studies of the association between these factors and alcohol access.

We believe that public health professionals and policymakers should consider variations in retail alcohol exposure among disparate groups. The strong association between retail alcohol density and predictors of health disparities may have implications at both the individual and the community levels, creating an opportunity to reduce the risks of morbidity and mortality in the community.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA77026 and AA015591).

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because this study used publicly available US Census data and commercially available information on retail stores.

References

- 1.Alaniz ML. Alcohol availability and targeted advertising in racial/ethnic minority communities. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(4):286–289 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romley JA, Cohen D, Ringel J, Sturm R. Alcohol and environmental justice: the density of liquor stores and bars in urban neighborhoods in the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(1):48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gliksman L, Rush BR. Alcohol availability, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related damage. II. The role of sociodemographic factors. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47(1):11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Rerner LG, Lery B, Needell B. Exploring the spatial dynamics of alcohol outlets and child protective services referrals, substantiations, and foster care entries. Child Maltreat. 2007;12(2):114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuntsche E, Kuendig H, Gmel G. Alcohol outlet density, perceived availability and adolescent alcohol use: a multilevel structural equation model. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(9):811–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts RK, Rabow J. Alcohol availability and alcohol-related problems in 213 California cities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7(1):47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Ring L, LaScala EA. An ecological assessment of the population and environmental correlates of childhood accident, assault, and child abuse injuries. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(11):1969–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW, Treno AJ. Outlets, drinking and driving: a multilevel analysis of availability. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(4):460–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorman DM, Speer PW, Gruenewald PJ, Labouvie EW. Spatial dynamics of alcohol availability, neighborhood structure and violent crime. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(5):628–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluthenthal RN, Cohen DA, Farley TA, et al. Alcohol availability and neighborhood characteristics in Los Angeles, California and southern Louisiana. J Urban Health. 2008;85(2):191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freisthler B, Midanik LT, Gruenewald PJ. Alcohol outlets and child physical abuse and neglect: applying routine activites theory to the study of child maltreatment. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(5):586–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaVeist TA, Wallace JM., Jr Health risk and inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(4):613–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scribner R, Cohen D, Kaplan S, Allen SH. Alcohol availability and homicide in New Orleans: conceptual considerations for small area analysis of the effect of alcohol outlet density. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60(3):310–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scribner RA, Cohen DA, Fisher W. Evidence of a structural effect for alcohol outlet density: a multilevel analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):188–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruenewald PJ, Freisthler B, Remer L, LaScala EA, Treno A. Ecological models of alcohol outlets and violent assaults: crime potentials and geospatial analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(5):666–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oak Ridge National Laboratory LandScan Global Population Database. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Available at: http://www.ornl.gov/sci/landscan. Accessed October 27, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Census Bureau Census 2000 Summary File 1. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Census Bureau Census 2000 Summary File 3. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of Washington, Seattle. Using RUCA data. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php. Accessed June 29, 2010

- 20.Washington State Department of Health A four-tier consolidation of the RUCA system at the sub-county level. Available at: http://www.doh.wa.gov/Data/guidelines/RuralUrban2.htm#fourtier. Accessed June 29, 2010

- 21.Gruenewald PJ. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(6):870–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Openshaw S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem. Norwich, UK: GeoBooks; 1984. Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography; vol 38 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorman DM, Speer PW. The concentration of liquor outlets in an economically disadvantaged city in the northeastern United States. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32(14):2033–2046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]