Abstract

Objectives. We conducted a trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a cervical cancer control intervention for Vietnamese American women that used lay health workers.

Methods. The study group included 234 women who had not received a Papanicolaou (Pap) test in the last 3 years. Experimental group participants received a lay health worker home visit. Our trial endpoint was Pap test receipt within 6 months of randomization. Pap testing completion was ascertained through women's self-reports and medical record reviews. We examined intervention effects among women who had ever received a Pap test (prior to randomization) and women who had never received a Pap test.

Results. Three quarters of the women in the experimental group completed a home visit. Ever-screened experimental group women were significantly more likely to report Pap testing (P < .02) and to have records verifying Pap testing (P < .04) than were ever-screened control group women. There were no significant differences between the trial arms for women who had never been screened.

Conclusions. Our findings indicate that lay health worker–based interventions for Vietnamese American women are feasible to implement and can increase levels of Pap testing use among ever-screened women but not among never-screened women.

Over 10% of Asian Americans are of Vietnamese descent, and the Vietnamese American population now exceeds 1 250 000.1 The majority of Vietnamese Americans came to the United States as refugees or immigrants over the last 3 decades.2 Cancer registry data show that in the United States, the incidence rate of cervical cancer among Vietnamese women is over twice that among non-Hispanic White women (16.8 vs 8.1 per 100 000).3 Further, the President's Advisory Commission on Asian Americans recently identified cervical cancer among Vietnamese women as one of the most important health disparities experienced by Asian American populations.4

According to American Cancer Society guidelines, women should be screened for cervical cancer every 1 to 3 years, depending on their risk factors for disease and previous screening history.5 Additionally, national cervical cancer screening goals for the year 2010 specify that at least 97% of women should have received a Papanicolaou (Pap) test on at least 1 occasion, and 90% of women should have received a Pap test within the previous 3 years.6 However, California survey data for 2003 indicated that only 70% of Vietnamese women aged 18 years and older had received Pap testing in the previous 3 years, compared with 84% of White, 87% of Black, and 85% of Hispanic women.7

Lay health workers are community members who are not certified health care professionals, but have been trained to promote health or provide health care services within their community. The Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews recently concluded that interventions based on lay health workers represent a promising approach to disease prevention, and recommended further research on the effectiveness of approaches using lay health workers for different health topics and demographic population subgroups.8 We have previously described our development of a cervical cancer control intervention for Vietnamese American women that used lay health workers.9 In this report, we provide findings from our randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the lay health worker–based intervention in improving levels of Pap test receipt among Vietnamese immigrants in Washington State.

METHODS

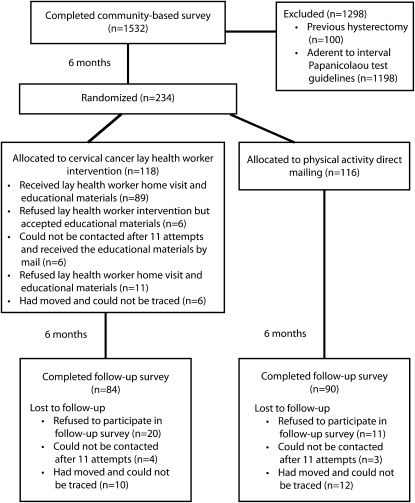

The study design is summarized in Figure 1. Trial participants were women who participated in a community-based survey conducted in metropolitan Seattle, Washington, over a 12-month period during 2006 and 2007. Women were eligible for participation in our community-based survey if they were of Vietnamese descent, aged 20 to 79 years, and able to speak Vietnamese or English. The survey was conducted face-to-face in women's homes. Respondents provided information about their Pap test history and demographic characteristics. A total of 1532 women completed surveys, and the survey response rate was 72%. Our sampling and survey methods have been described in detail elsewhere.10,11

FIGURE 1.

Overview of a cervical cancer control intervention using lay health workers: Vietnamese American women, Seattle, WA, 2006–2007.

Community-based survey respondents were eligible for the trial if they had a uterus and did not adhere to guidelines for interval Pap testing. Because regular Pap testing is no longer recommended for women aged 70 to 79 years who have a history of previous testing, survey respondents in this age group were eligible only if they had never been screened. Women aged 20 to 69 years were eligible if they had not been screened for cervical cancer in the previous 3 years.5

Eligible women were randomized into the trial 6 months after they participated in the community-based survey. Immediately after randomization, individuals in the experimental group received a cervical cancer control intervention using lay health workers (which included the use of audiovisual and print educational materials); control group participants received a mailing of physical activity print materials (pamphlet and fact sheet), as well as a pedometer with instructions for use.

Our primary trial outcome was completion of Pap testing within 6 months of randomization. Outcome ascertainment was based on responses to a follow-up survey. We also attempted to use medical records to verify self-reports of Pap testing in the interval between randomization and completion of the follow-up survey.

All study materials were translated into Vietnamese by standard methods.12 All project personnel who had direct contact with participants (survey interviewers and lay health workers) were bicultural, bilingual Vietnamese American women.

Consent Procedures

Participants provided written consent for the community-based survey, trial follow-up survey, and release of medical records, as well as verbal consent for the lay health worker–based intervention. During the community-based survey consent process, women were explicitly told that they might be offered health education in the future (if they participated in the community-based survey).

Randomization

We randomized 234 women into the trial. Our random assignment was performed separately for the women who had never received a Pap test (n = 106) and the women who had received at least 1 Pap test but had not been screened recently (n = 128). A project coordinator assigned women to the experimental or control group by using computer-generated randomization lists. The randomization order was based on date of completion of the community-based survey.

Educational Materials

We used findings from an earlier qualitative study to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate materials for use in the cervical cancer control intervention using lay health workers. Our material development has been described in detail elsewhere.9 Project materials included a Vietnamese-language DVD (with English subtitles) and a pamphlet (with both Vietnamese and English text). These materials provided basic information about cervical cancer and the Pap test (within the context of Vietnamese traditional beliefs about women's health) and emphasized the importance of Pap testing for all women (including those who are asymptomatic, not currently sexually active, or postmenopausal). Several visual aids were also developed by the project: a graph showing cervical cancer incidence rates by race/ethnicity, a gynecologic anatomy diagram, and a figure showing how cervical cancer progresses.

Lay Health Workers

Two lay health workers were selected, both of them fluently bilingual ethnic Vietnamese women who had grown up in Vietnam and were conversant with Vietnamese culture. These women were married with children, which would help traditional Vietnamese participants feel comfortable and confident about discussing reproductive concerns with them. Neither of the lay health workers was a certified health professional. The lay health workers were trained to act as role models, give social support, and provide tailored responses to each woman's individual barriers to Pap testing (e.g., believing that Pap testing is unnecessary for asymptomatic women).9

Lay Health Worker–Based Intervention

Lay health workers made up to 11 attempts to complete a home visit with each experimental group participant. Women who refused a home visit were offered the educational materials (DVD and pamphlet). If a lay health worker was unable to contact a participant, the educational materials were mailed to her home. During home visits, lay health workers systematically asked participants if they could watch the DVD together, offered participants a copy of the DVD and pamphlet, and showed participants the visual aids. Finally, the lay health workers attempted to complete follow-up telephone calls with participants 1 month after completed home visits to offer further assistance, as necessary.

Follow-Up Survey

To trace individuals who had recently moved, we used contact information for friends or relatives (provided at the time of the baseline survey) and the national change-of-address system. Interviewers made up to 11 follow-up attempts to contact (including weekday, weekend, and evening attempts). All follow-up interviews were conducted face-to-face in participants' homes. Respondents received a small financial incentive for completing the follow-up survey. Each respondent to the follow-up survey was asked whether she had ever had a Pap test and, if so, when she was last screened. Other questions assessed exposure to the Pap testing educational materials. Interviewers in the follow-up survey were unaware of each participant's trial randomization assignment.

Medical Record Reviews

Respondents to the follow-up survey who reported that they had received Pap testing in the 6-month interval since their random assignment were asked to provide information about the date of testing, as well as the name and location of the clinic or doctor's office where testing was performed. Each of these participants was also asked to sign a medical release form giving project staff permission to request medical record verification of her self-reported Pap test. A copy of the Pap test result was then requested (from the relevant clinic or doctor's office) via a form that provided the participant's name, age, and self-reported date of testing. The project staff contacted each health care facility up to 3 times (twice by mail and once by telephone).

Process Evaluation

Process data were collected to document the implementation and content of our cervical cancer control intervention. Specifically, lay health workers routinely completed forms addressing the outcome of home visit attempts (e.g., agreed to participate in a home visit, refused a home visit but accepted the educational materials, or refused a home visit and the health education materials). Lay health workers also documented use of the project DVD, pamphlet, and visual aids, as well as follow-up telephone calls. A home visit was considered complete if the lay health worker was able to complete a discussion about Pap testing at a woman's home.

Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcome analysis included all randomized individuals and assumed that participants without follow-up data were not screened after randomization. We also conducted a secondary outcome analysis that included only randomly assigned women with follow-up data. Experimental group women who did not receive the cervical cancer control intervention were included in study analyses. Our outcome evaluation was conducted with follow-up survey data and then repeated with medical records data. We conducted stratified analyses and examined intervention effects among women who had ever received a Pap test (prior to randomization) and women who had never received a Pap test (as well as among the study group as a whole). The Fisher exact test was used to evaluate statistical significance with respect to differences in proportions between the arms. Unconditional logistic regression was also performed to adjust the intervention effect for demographic variables.

RESULTS

Our follow-up survey response is detailed in Figure 1. Eighty-four (71%) of the 118 women who were randomized to the experimental arm and 90 (78%) of the 116 women who were randomized to the control arm completed follow-up surveys. The proportions of women in the experimental and control groups who provided follow-up data were not significantly different.

Study Group Characteristics

Only 1 of the trial participants who completed a follow-up survey (randomized to the experimental arm) was born in the United States. The baseline characteristics of all women assigned to the experimental and control arms are given in Table 1. Our 2 trial groups were equivalent with respect to demographic characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Vietnamese American Women Randomized to Experimental and Control Arms of a Cervical Cancer Control Intervention Using Lay Health Workers: Seattle, WA, 2006–2007

| Characteristic | Experimental Group (n = 118), No. (%) | Control Group (n = 116), No. (%) | P |

| Age, y | .51 | ||

| < 50 | 56 (47) | 49 (43) | |

| ≥ 50 | 62 (53) | 65 (57) | |

| Education, y | .69 | ||

| < 12 | 64 (54) | 59 (51) | |

| ≥ 12 | 54 (46) | 57 (49) | |

| Marital status | .49 | ||

| Currently married | 77 (65) | 81 (70) | |

| Not currently married | 41 (32) | 35 (30) | |

| Years in United States | .13 | ||

| < 15 | 83 (70) | 70 (61) | |

| ≥ 15 | 35 (30) | 45 (39) | |

| English proficiency | .6 | ||

| Does not speak well or at all | 50 (42) | 54 (47) | |

| Speaks well or fluently | 68 (58) | 62 (53) | |

| Pap testing history | .9 | ||

| Ever screened | 64 (54) | 64 (55) | |

| Never screened | 54 (46) | 52 (45) |

Note. Pap test = Papanicolaou test. Numbers may not total to the full sample because of missing data.

Medical Records Verification

Twenty-eight participants in the experimental group and 16 in the control group reported that they had received a Pap test in the 6-month interval between randomization and follow-up. We were able to request medical records for 25 of the 28 experimental group participants and all 16 of the control group participants. (The 3 other participants refused to sign a medical records release or provided insufficient information about the clinic where Pap testing was performed.) All of the health care facilities responded to our requests for information about cervical cancer screening. Medical records verified self-reported Pap testing for 18 (64%) of the 28 experimental group women and 8 (50%) of the 16 control group women who self-reported Pap testing.

Outcome Analyses

Table 2 provides findings from our primary outcome analyses (all randomized women), as well as our secondary outcome analyses (all women with follow-up data). Among all randomized women, 24% of the experimental group reported Pap testing after randomization, compared with 14% of the control group (P = .07). Medical records verified Pap test receipt for 15% of the 118 experimental group participants and 7% of the 116 control group participants (P = .06). Our stratified analyses documented an intervention effect for women who had received at least 1 Pap test during their lifetime (but had not received a Pap test in the 3 years prior to randomization). Among women who had never been screened for cervical cancer at baseline, there were no significant differences in Pap testing completion rates between the experimental and control groups. Findings from the unadjusted analyses were unchanged in logistic regression analyses (with adjustment for demographic characteristics).

TABLE 2.

Papanicolaou (Pap) Testing Among Vietnamese American Women Randomized to Experimental and Control Arms of a Cervical Cancer Control Intervention Using Lay Health Workers: Seattle, WA, 2006–2007

| Group | Experimental Group, No. (%) | Control Group, No. (%) | P | AORa (95% CI) |

| All randomized womenb | ||||

| Self-reported Pap testing | ||||

| All women | 28 (24) | 16 (14) | .07 | 1.78 (0.88, 3.60) |

| Ever-screened women | 20 (31) | 8 (13) | .02 | 3.15 (1.20, 8.27) |

| Never-screened women | 8 (15) | 8 (15) | >.99 | 0.85 (0.28, 2.58) |

| Pap testing verified by medical records | ||||

| All women | 18 (15) | 8 (7) | .06 | 2.37 (0.94, 5.97) |

| Ever-screened women | 13 (20) | 4 (6) | .03 | 3.63 (1.06, 12.45) |

| Never-screened women | 5 (9) | 4 (8) | >.99 | 1.00 (0.24, 4.19) |

| Women with follow-up datac | ||||

| Self-reported Pap testing | ||||

| All women | 28 (33) | 16 (18) | 0.02 | 2.17 (1.03, 4.56) |

| Ever-screened women | 20 (43) | 8 (16) | 0.004 | 4.25 (1.50, 12.01) |

| Never-screened women | 8 (22) | 8 (21) | >.99 | 0.80 (0.25, 2.60) |

| Pap testing verified by medical records | ||||

| All women | 18 (21) | 8 (9) | 0.03 | 2.84 (1.09, 7.39) |

| Ever-screened women | 13 (28) | 4 (8) | 0.01 | 4.59 (1.28, 16.48) |

| Never-screened women | 5 (14) | 4 (10) | 0.73 | 1.17 (0.26, 5.30) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. In the experimental group, percentages reflect within-sample percentages, not total sample percentages.

Adjusted for age, education, marital status, years in United States, and English proficiency.

For the experimental group, the sample size was n = 118; for the control group, the sample size was n = 116.

For the experimental group, the sample size was n = 84; for the control group, the sample size was n = 90.

Process Measures

Lay health workers were able to complete home visits with 75% of the women randomized to our experimental arm (Figure 1). The remaining women refused a home visit but accepted the educational materials (5%), could not be contacted after 11 attempts and received the educational materials by mail (5%), refused a home visit and the educational materials (9%), or had moved and could not be traced (5%). Twenty-five of the 28 experimental group women who reported a Pap test at follow-up had completed a home visit with a lay health worker (1 woman had received the educational materials by mail and 2 had refused the home visit and educational materials).

Project personnel reported watching the DVD with 80% of the 89 home-visit participants. Our 3 visual aids were shown during 94% of home visits, and the DVD and pamphlet were both provided at the end of all visits by lay health workers. Follow-up telephone calls were successfully completed with 84% of the home-visit participants. Three quarters (75%) of the 84 experimental-arm women with follow-up data reported that they had watched the DVD and 55% reported that they had read the pamphlet.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that lay health worker–based interventions for Vietnamese American women are acceptable to the community, are feasible to implement, and can increase levels of Pap testing use among women who have previously been screened for cervical cancer (but are nonadherent with guidelines for interval screening). Specifically, 84% of the 106 women that our lay health workers were able to contact completed a home visit. Additionally, we demonstrated an intervention effect among previously screened women by using a conservative approach that assumed that all women without follow-up data were unscreened, as well as that failure to retrieve a medical record of Pap testing always meant that the woman was truly unscreened.

A previous California study13 randomized Vietnamese American women to lay health worker–conducted group education plus media-based education (combined intervention) or to media-based education alone (media-only intervention). Women provided information about their Pap testing history 4 months after randomization. The combined intervention was more effective than the media-only intervention in increasing the rate of previous Pap testing receipt (from 66% to 82% vs 70% to 76%; P < .001). Among those who had never been screened, significantly more women in the combined intervention group (46%) than in the media-only group (27%) obtained Pap tests (P < .001).13 It is possible that the California intervention for previously unscreened women was more effective than our intervention because of differences in the intervention intensity or components. Specifically, the California intervention included 2 face-to-face educational sessions with lay health workers (rather than 1 face-to-face educational session) and use of a flipchart (rather than a DVD).

In our study, 33% of experimental group women with follow-up data and 18% of control group women with follow-up data reported Pap testing (P = .02). Previous studies have evaluated lay health worker–based interventions for women among other racial/ethnic minority groups who are nonadherent to Pap testing guidelines, with similar results. Another Washington State study focused on Chinese American women. Six months after randomization, 37% of the experimental group and 22% of the control group reported Pap testing (P = .07).14 A Texas study focused on low-income Hispanic women. Interviews with the women 6 months after the intervention revealed that Pap testing completion was significantly higher among the experimental group (40%) than among the control group (24%).15

Our study's strengths included a randomized controlled design, as well as use of both self-report and medical records data for endpoint ascertainment. Several studies have found that the accuracy of screening test self-reports among Asian American women is relatively low, compared with the accuracy among non-Hispanic White women.16,17 For example, one study was able to verify self-reports of Pap testing for 85% of non-Hispanic White women but for only 68% of Chinese women and 67% of Filipina women.16 We were able to request medical records for 41 (93%) of the 44 women who reported Pap testing following randomization, and were able to verify Pap testing for 24 (59%) of these 41 women. Asian naming systems may result in misfiling of test results and difficulty finding medical records. It is therefore possible that at least some of the women whose self-reported recent Pap testing could not be verified had in fact received a recent Pap test.

Our study had several limitations that should be recognized. First, we recruited individuals living in one geographic area of the United States, and the results may not be applicable to all Vietnamese American women. Second, only individuals who agreed to complete a baseline survey were eligible for participation in the trial, and survey responders may be more receptive to health education programs than survey nonresponders. Third, although we requested the medical records of all individuals who reported Pap testing since randomization, we made no attempt to verify the accuracy of self-reports among women who reported that they had not been tested. It is possible that some of these individuals received a Pap test, without their knowledge, during a gynecologic examination for a health problem. Finally, our follow-up interval was only 6 months, and some trial participants may have received Pap testing after their follow-up survey.

Our results add to the evidence concerning the effectiveness of approaches using lay health workers to control cervical cancer among Vietnamese and other Asian immigrant communities.13,14,18 Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of lay health education for other racial/ethnic minorities and groups with limited English proficiency, as well as other screening modalities (e.g., fecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy). It will also be important for researchers to conduct dissemination studies focusing on the adaptation and implementation of cervical cancer control interventions using lay health workers in community health centers and other community-based organization settings.15

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA-115564), a cooperative agreement from the National Cancer Institute (U01-CA-114640), and a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48-DP-000050).

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's institutional review board.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau The American Community–Asians: 2004. American Community Survey Reports. Washington, DC: US Dept of Commerce; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan S, Lee E. Families with Asian roots. : Lynch EW, Hanson MJ, Developing Cross-Cultural Competence. Baltimore, MD: Paul Brookes Publishing; 2004:241–245 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, Ries LA. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(3):227–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.President's Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders—Addressing Health Disparities: Opportunities for Building a Healthier America. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2003:21–23 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):342–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2000:3–23 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holtby S, Zahnd E, Lordi N, McCain C, Chia YJ, Kurata J. Health of California's Adults, Adolescents, and Children. Sacramento: California Dept of Health Services; 2006:23 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewin SA, Dick J, Pond P, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Libr. 2005;(1):2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke NJ, Jackson JC, Lam DH, et al. Good health for New Years: development of a cervical cancer control outreach program for Vietnamese immigrants. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(4):244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Nguyen T, et al. Pap smear receipt among Vietnamese immigrants: the importance of health care factors. Ethn Health. 2009;14(6):575–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor VM, Nguyen TT, Do HH, Li L, Yasui Y. Lessons learned from the application of a Vietnamese surname list for survey research. J Immigr Minor Health. October 2, 2009 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ, et al. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(2):212–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock J, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, et al. Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1693–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Jackson JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to promote cervical cancer screening among Chinese women in North America. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):670–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Saavedra-Embesi M, Chan W, Vernon SW. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: a breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):936–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPhee SJ, Nguyen TT, Shema SJ, et al. Validation of recall of breast and cervical cancer screening by women in an ethnically diverse population. Prev Med. 2002;35(5):463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasick R, Stewart S, Bird J, D'Onofrio C. Quality of data in multiethnic health surveys. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(suppl 1):223–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird JA, McPhee SJ, Ha NT, Le B, Davis T, Jenkins CNH. Opening pathways to cancer screening for Vietnamese-American women: lay health workers hold a key. Prev Med. 1998;27(6):821–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]