Abstract

Prize-based contingency management (CM) is efficacious in treating cocaine abuse, and the chance-based procedures of prize CM may be appealing to those who gamble. Using data from three randomized trials, we evaluated whether cocaine abusers who had wagered in the month before treatment (n = 62) responded more favorably to prize CM than those who had not (n = 278). Participants were randomized to standard care (SC) or SC plus prize CM. Although prize CM was related to better outcomes overall, recent gambling was not associated with outcomes across or within treatment conditions. Gambling participation before treatment entry was associated with reductions in gambling over time, and this effect was more pronounced among those assigned to CM. These data suggest that prize CM is equally efficacious for substance abusers who do and do not gamble, and they extend prior studies indicating that prize CM does not increase gambling.

Keywords: treatment outcome, contingency management, cocaine dependence, gambling

1. Introduction

Contingency management (CM) treatments are highly efficacious in decreasing drug use (Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, & Badger, 2006; Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006). In these interventions, participants receive tangible reinforcers, such as retail goods and services, upon objective evidence of behavior change, such as submission of drug-negative urine samples (Petry, 2000). A recent meta-analysis of psychosocial treatments (Dutra et al., 2006) found CM to be the intervention with the greatest effect size in treating substance use disorders.

Prize CM was popularized with the completion and dissemination of the National Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (NIDA CTN) studies (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005a). In these treatments, participants earn the opportunity to draw from a bowl and win prizes of varying magnitudes for submitting drug negative urine samples. Randomized trials have established the efficacy of prize CM in reducing drug use across a variety of substance abusing populations and settings (Alessi, Hanson, Tardif, & Petry, 2007; Alessi, Petry, & Urso, 2008; Ghitza et al., 2007; Ledgerwood, Alessi, Hanson, Godley, & Petry, 2008; Peirce et al., 2006; Petry, Martin, Cooney, & Kranzler, 2000; Petry, Martin, & Finocche, 2001a; Petry et al., 2004, 2005a; Petry, Alessi, Marx, Austin, & Tardif, 2005b; Petry, Martin, & Simcic, 2005c; Petry et al., 2006a; Petry, Alessi, Hanson, & Sierra, 2007; Petry, Weinstock, Alessi, Lewis, & Dieckhaus, 2010; Preston, Ghitza, Schmittner, Schroeder, & Epstein, 2008; Tracy et al., 2007).

Because not every drug-negative sample results in tangible reinforcement, this treatment contains an element of chance, and participants typically win prizes 50% of the time they earn draws. Further, the amount of reinforcement varies randomly, such that most often patients win small $1 prizes, other times $20 prizes, and on rare occasion $100 prizes. Due to the chance-based nature of the procedures, some have expressed concern that prize CM may promote increased gambling (Petry et al., 2006b). Given the high rates of co-morbidity between substance abuse and pathological gambling (Gerstein et al., 1999; Kessler et al., 2008; Petry, Stintson, & Grant, 2005d; Welte, Barnes, Weiczorek, Tidwell, & Parker, 2001), patients in recovery from pathological gambling are excluded from participating in prize CM treatments. However, to date, this criterion has only excluded nine patients screened in CM studies (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005a,b,c, 2006a, 2007, 2010). Further, prize CM is not gambling, because by definition gambling involves risking something of value. In prize CM treatments, participants do not risk anything, and they only stand to gain.

Petry et al. (2006b) evaluated the effects of prize CM on gambling among 803 stimulant abusing patients participating in the NIDA CTN trials of prize CM. Gambling was assessed before, during, and 3 months after study initiation in patients randomly assigned to standard care or standard care plus prize CM for 12 weeks. No differences in gambling over time were noted between those assigned to the prize CM versus standard care conditions, and not a single patient receiving prize CM developed clinically significant increases in gambling (Petry et al., 2008). These data provide evidence that the prize CM procedure does not increase gambling in stimulant abusers who are not in recovery from pathological gambling.

Although prize CM does not increase gambling, gambling participation rates vary across individuals, and substance abusers who gamble are likely to differ from those who do not. For example, recreational gamblers have more psychiatric, substance use, and legal problems than non-gamblers (Cunningham-Williams et al., 2000; Desai, Maciejewski, Pantalon, & Potenza, 2006; Morasco, vom Eigen, & Petry, 2006; Pietrzack, Morasco, Blanco, Grant & Petry, 2007; Westermeyer et al., 2008). Recreational gamblers with substance abuse disorders are likely to be male, unmarried, and have an early onset of gambling (Lui, Maciejewski, & Potenza, 2009). Although Hall et al. (2000) did not find that gambling status was associated with retention or drug abuse treatment outcomes, Ledgerwood and Downey (2002) reported that methadone patients identified with gambling problems were more likely than their non-gambling counterparts to use cocaine and drop out of substance abuse treatment prematurely. Thus, substance abusers who gamble may have poorer treatment outcomes than those who do not.

On the other hand, prize CM may be appealing to substance abusers who gamble. Because of the chance-based procedures, individuals who engage in gambling activities on their own may find prize CM particularly reinforcing, and they may be more likely to remain involved in prize CM treatments than participants who do not gamble.

The primary purpose of this study was to examine main and interactive effects of gambling participation and treatment condition (standard care or CM) to determine whether prize CM was more efficacious among substance abusers who gamble than their counterparts who do not gamble. This question has never before been empirically addressed. In addition, to confirm and extend prior studies on the safety of prize CM, we also examined if participation in prize CM treatments impacted gambling behaviors over time.

2. Method

Participants

We analyzed data from participants (n = 393) enrolled in one of three randomized studies of prize-based CM (Petry et al., 2004; Petry et al., 2005b; Petry et al., 2006a). Inclusion criteria in all three studies were initiating outpatient treatment at one of four community-based substance abuse treatment programs, age 18 or older, past-year Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for cocaine abuse or dependence, and able to comprehend study procedures. Exclusion criteria were significant uncontrolled psychopathology (e.g., active suicidal ideation, mania, psychosis), and in recovery for pathological gambling, although no potential subjects in these studies were excluded for this reason. The four clinics provided similar treatment services, and mean age, years of cocaine use, and education level of participants did not differ across clinics (all p's > .05). Participants provided written informed consent, approved by the university's Institutional Review Board. Study procedures were in accord with the standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation of the institution in which the experiments were done and in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Procedures

This study is a retrospective analysis of data collected in three clinical trials (Petry et al., 2004; Petry et al., 2005b; Petry et al., 2006a). All studies evaluated the efficacy of one or more prize CM conditions when added to standard care (SC) relative to SC alone. The CM conditions varied across studies, and reinforced either abstinence from substances or completion of goal-related activities or both. One study (Petry et al., 2005b) also included a second CM condition that employed a voucher-based CM approach, and the 53 participants assigned to this condition were not included in the present report because they were not exposed to prize CM, leaving 340 participants for analysis. The three trials had equal treatment durations and intensities and assessed outcomes using the same instruments and at the same time intervals, providing a rationale for combining results from the SC and the CM conditions across studies.

Participants provided demographic information and completed baseline questionnaires. Modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) evaluated psychiatric disorders. The Addiction Severity Index assessed psychosocial functioning in seven domains: alcohol use, drug use, medical, employment, legal, family/social relationships, and psychiatric. Composite scores provide information on the severity of problems in each domain; these scores range from 0.00 to 1.00, with higher scores indicating greater problems.

The ASI has been adapted to include a gambling section. This section includes items about past month days and dollars wagered, along with days experienced self-reported gambling problems and subjective reports of being troubled by gambling problems. The ASI-Gambling section has good internal consistency, test-retest reliability and validity in assessing gambling in both primary gamblers and in substance abusers (Lesieur & Blume, 1991; Petry, 2003; Petry, 2007). In addition, days and dollars wagered in the past month as determined by the ASI are highly correlated with collateral reports of frequencies and amounts gambled (Petry et al., 2006c).

At baseline and during the 12-week treatment programs, participants provided urine samples that were tested for cocaine and opioids using OnTrak TesTstiks (Varian Inc., Walnut Creek, CA) and breath samples that were screened for alcohol using the Alco-sensor IV Alcometer (Intoximeters, St. Louis, MO). Sample collection was scheduled for 3 days per week in weeks 1–3 (e.g., Monday, Wednesday, and Friday), 2 days per week in weeks 4 through 6 (e.g., Tuesday and Friday), and 1 day per week in weeks 7 through 12. Although the number of scheduled samples was 21 in all studies and conditions, the number of samples submitted differed across studies (Petry et al., 2004: M = 9.3, SD = 6.0; Petry et al., 2005b: M = 12.2, SD = 5.9; Petry et al., 2006a: M = 11.1, SD = 5.4), F (2, 337) = 6.69, p < .001, and treatment condition (SC: M = 9.3, SD = 5.3; CM: M = 11.6, SD = 6.0), F (1, 338) = 11.96, p < .001. Thus, in order to include an outcome variable that was unaffected by missing samples, we also report upon percent negative samples submitted.

Research staff scheduled post-treatment evaluations 3 months after treatment initiation. At the evaluation, participants completed the ASI and submitted urine and breath samples. Depending on the study, they received payments of $30 – $35 for completing the post-treatment evaluation, and the overall completion rate was 82.6%, which did not differ by baseline gambling participation status, treatment condition, or study (all p's > .13).

Treatments

After completing the baseline evaluation, participants were randomly assigned to a treatment condition. The main papers provide full descriptions of the treatments (Petry et al., 2004, 2005b, 2006a), and only brief overviews are described below.

Standard Care

The three studies each provided intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment. It consisted of group therapy sessions, which discussed topics such as relapse prevention, coping and life skills training, AIDS education, and 12-step involvement. During the initial 2 – 4 week intensive phase, group sessions occurred on 3 – 5 days per week. Aftercare consisted of one group per week and was provided for up to 12 months. In addition to this SC, study participants submitted up to 21 breath and urine specimens as described earlier.

Prize CM

In addition to SC described above, participants assigned to prize CM conditions received reinforcement for submitting negative urine and breath samples and/or completing goal-related activities. Abstinence was reinforced when samples tested negative for all three substances tested: alcohol, cocaine, and opioids. To receive reinforcement for activities, participants completed objectively verifiable tasks consistent with their treatment plans (e.g., if a goal was medical, then an activity may be attending a doctor's appointment and providing a receipt; see Petry, Tedford, & Martin, 2001b). For conditions in which both activities and abstinence were targeted, reinforcement schedules were independent, such that failure to complete activities did not affect abstinence reinforcement and vice versa.

Data Analysis

Participants were divided into two groups based on their response to an item in the baseline ASI-Gambling section: how many days in the past month have you wagered in any form, including lotteries, scratch tickets, bingo, slots or other casino games, card games, sports, etc.? Those who reported gambling on one or more days were compared with those who had not wagered at all with respect to demographic and baseline variables using independent t-tests and χ2 tests. Although not all continuous variables were normally distributed, t-tests are robust to departures from normality when sample size is large (Lumley, Diehr, Emerson, & Chen, 2002), and non-parametric tests yielded similar results to those reported herein.

MANCOVA was used to examine the relationship between recent gambling participation and primary treatment outcomes: weeks retained in treatment, longest duration of abstinence (LDA), and percent negative samples submitted. LDA was defined as the highest number of consecutive weeks of objectively verified abstinence from alcohol, cocaine, and opioids (range = 0 – 12 weeks). Positive samples for one or more drugs, and unexcused or missed samples, broke the period of abstinence. The percent negative samples submitted (for cocaine, alcohol, and opioids) was calculated with the number of samples submitted in the denominator, such that missing samples did not impact this variable. Independent variables included main and interaction effects of gambling participation status (no recent gambling vs. recent gambling), treatment condition (SC or CM), and study (Petry et al., 2004, or 2005b, or 2006a).

We also assessed if any changes in gambling occurred over time. ASI-gambling composite scores at the baseline evaluation were subtracted from ASI-gambling composite scores obtained at the post-treatment evaluation such that a change score was derived. These change scores were normally distributed and served as the dependent variable. Univariate analysis of variance evaluated the impact of pre-treatment gambling status, treatment condition, and study, along with the interaction effects of these variables, on ASI-gambling change scores. Analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows (v.15).

3. Results

Table 1 presents demographic and baseline characteristics of participants with and without recent gambling participation. Compared to those who had not wagered in the month before starting treatment, those who had wagered were significantly more likely to be male and enrolled in the Petry et al. (2004) and (2006a) studies relative to the Petry et al. (2005b) study. Participants with recent gambling participation were also significantly more likely to have higher incomes and more medical and alcohol problems, but fewer employment problems, than those who had not gambled in the month before starting outpatient treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline and Demographic Characteristics by Recent Gambling Participation Status

| Variables | No recent gambling participation | Recent gambling participation | Statistic (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 278 | 62 | ||

| Treatment Condition | χ2 (1) = 0.000 | .99 | ||

| Standard Care | 33.8 (94) | 33.9 (21) | ||

| CM + Standard Care | 66.2 (184) | 66.1 (41) | ||

| Study | χ2 (2) = 9.26 | .01 | ||

| Petry et al. (2004) | 34.5 (96) | 38.7 (24) | ||

| Petry et al. (2005b) | 29.5 (82) | 11.3 (7) | ||

| Petry et al. (2006a) | 36.0 (100) | 50.0 (31) | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 36.2 (8.2) | 36.8 (8.5) | t (338) = −0.50 | .62 |

| Male Gender | 47.1 (131) | 71.0 (44) | χ2 (1) = 11.54 | .00 |

| Race | χ2 (2) = 5.14 | .08 | ||

| African American | 54.8 (149) | 41.9 (26) | ||

| Caucasian | 33.1 (90) | 48.4 (30) | ||

| Other | 12.1 (33) | 9.7 (6) | ||

| Marital Status- Single | 53.6 (149) | 48.4 (30) | χ2 (1) = 0.62 | .74 |

| Employed Full-time | 42.8 (119) | 67.7 (44) | χ2 (1) = 12.64 | .00 |

| Income (mean, SE) | $9,493 ($932) | $13,755 ($1770) | t (338) = −2.0 | .05 |

| Variables | No recent gambling participation | Recent gambling participation | Statistic (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Education (mean, SD) | 11.5 (0.11) | 11.9 (0.16) | t (338) = −1.6 | .10 |

| Negative Baseline Toxicology (for opioids, cocaine and alcohol) | 81.6 (226) | 79.0 (49) | χ2 (1) = 0.22 | .64 |

| DSM-IV Alcohol Dependence | 51.1 (142) | 58.1 (36) | χ2 (1) = 0.99 | .32 |

| DSM-IV Cocaine Dependence | 84.9 (236) | 88.7 (55) | χ2 (1) = 0.60 | .44 |

| Addiction Severity Index Scores (mean, SD) | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.23 (0.22) | 0.29 (0.25) | t (338) = −2.10 | .04 |

| Drug | 0.16 (0.09) | 0.16 (0.09) | t (338) = 0.27 | .79 |

| Medical | 0.21 (0.33) | 0.31 (0.36) | t (338) = −2.19 | .03 |

| Employment | 0.74 (0.29) | 0.62 (0.32) | t (338) = 2.94 | .00 |

| Legal | 0.13 (0.21) | 0.15 (0.22) | t (338) = −0.85 | .40 |

| Family/Social | 0.19 (0.23) | 0.22 (0.23) | t (338) = −0.90 | .37 |

| Psychiatric | 0.28 (0.24) | 0.31 (0.23) | t (338) = −0.88 | .38 |

| Gambling | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.11 (0.07) | t (338) = −24.34 | .00 |

| Past month days gambled | 0.0 (0.0) | 5.4 (6.6) | t (338) = −13.64 | .00 |

| Past month dollars wagered | 0.0 (0.0) | 69.8 (228.0) | t (338) = −5.74 | .00 |

| Past month days of gambling problems | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.1) | t (338) = −0.47 | .64 |

| How troubled by gambling problems in past month* | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | not applicable | |

Notes. Values denote percent (n) unless otherwise indicated.

Coded on a 0 to 4 likert scale.

CM = Contingency Management; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Revision IV.

Multivariate analyses found no statistically significant effects of recent gambling participation on the primary treatment outcomes, F (3, 328) = 0.97, p = .41. Table 2 shows the main outcomes (retention, LDA, and percent of negative sample) for patients with and without recent gambling activities, based on their treatment group assignment.

Table 2.

Treatment Outcomes by Baseline Recent Gambling Participation Status and Treatment Condition

| No recent gambling participation | Recent gambling participation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Treatment Outcomes | Standard Care | CM | Standard Care | CM |

| N | 94 | 184 | 21 | 41 |

| Retention in treatment (weeks) | 5.4 (0.4) | 7.5 (0.3) | 6.0 (0.8) | 7.6 (0.8) |

| Longest Duration of Abstinence (weeks) | 3.5 (0.4) | 5.7 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.9) | 5.3 (0.8) |

| Percent Negative Samples | 83.6 (2.8) | 85.1 (2.0) | 80.8 (6.2) | 84.7 (5.6) |

Notes. CM = Contingency management plus standard care. Values represent adjusted means and standard errors.

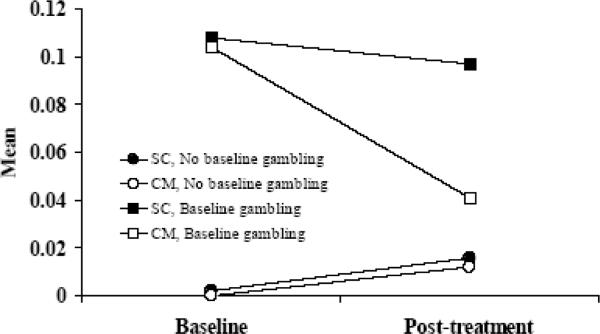

In evaluating the effects of baseline gambling participation, study, and treatment condition on ASI-gambling change scores, the interaction effect between baseline gambling participation and treatment condition was statistically significant, F (1, 271) = 4.47, p < .05. Those who initiated treatment having not gambled in the past month showed slight increases in ASI-gambling scores over time. As a group, those who began treatment having gambled in the prior month showed reductions in ASI-gambling scores over time, but these declines were particularly pronounced for those who were randomly assigned to CM relative to SC conditions. Figure 1 shows mean pre- and post-treatment ASI-gambling scores for participants with and without gambling participation at baseline and assigned to the two treatment conditions. Actual mean scores are presented rather than change scores for ease of interpretation. No other main or interaction effects were significantly associated with ASI-gambling change scores (p's > .05).

Figure 1.

Addiction-Severity Index Gambling scores at baseline and post-treatment. Mean values are plotted for patients randomized to contingency management treatment (CM; open symbols) and patients randomized to standard care treatment (SC; filled symbols). Patient groups are further divided based upon self-reports of any gambling in the month before baseline (squares) or not (circles).

4. Discussion

Data from this study are consistent with other reports (Cunningham-Williams et al., 2000; Petry, 2005) in that men were more likely to report recent gambling activities than women. While half the sample was male, males comprised 71% of the participants who had wagered in the month before initiating substance abuse treatment. In addition and similar to other studies (Desai et al., 2004; Pietrzak et al., 2007), cocaine abusers with recent gambling experience had more significant alcohol problems than their counterparts who had not recently gambled. However, contrary to most epidemiological studies that find gambling is associated with lower socioeconomic status (e.g., Gerstein et al., 1999; Welte et al., 2001), substance abusers who had recently gambled had higher incomes and lower employment problems than their counterparts who had not recently gambled. In part, the truncated socioeconomic group from which this sample was drawn may lead to differential results. In lower socioeconomic groups, having a larger income and full-time employment may allow more expendable funds for occasional gambling. In addition, the present sample contained no individuals with substantive self-reported gambling problems, and low socioeconomic status may be more strongly linked with gambling problems than gambling participation per se. Westermeyer et al. (2008) also noted that Native American recreational gamblers had greater social competence (higher incomes, more social stability) than their non-gambling counterparts.

Less than 20% of this sample wagered in the month before receiving substance abuse treatment. Even among those who had gambled, rates of gambling participation were fairly modest, with an average of 5 gambling days, and no one self-reported recent troubles related to gambling. This level of gambling appears low in drug abuse treatment populations, which find rates of problem and pathological gambling to be 5% to 20% (Cunningham-Williams et al., 2000; Hall et al., 2000; Steinberg, Kosten, & Rounsaville, 1992; Toneatto & Brennan, 2002). Although individuals in recovery from problem gambling would have been excluded from these studies, no potential participants were excluded for this reason. Rates of gambling participation would likely have been higher if greater than a 30-day window was evaluated. Further, the ASI assessed gambling participation and self-reported severity of gambling problems. Although reliable and valid for assessing the severity of gambling problems over time (Lusier & Blume, 1991; Petry, 2003, 2007), this instrument is not designed to diagnosis pathological gambling.

Gambling participation as defined by self reports of any gambling in the month before substance abuse treatment was not related to treatment outcomes, including retention, durations of abstinence achieved, or percent negative samples submitted. Those who had gambled and those who had not gambled evidenced similar retention and drug abuse treatment outcomes, regardless of the study in which they participated or the treatment intervention to which they were assigned. Thus, gambling participation status did not impact response to prize CM interventions, and gamblers and non-gamblers were equally likely to benefit from this treatment.

Consistent with other studies (Petry et al., 2006b, 2008), prize CM does not increase gambling. To the contrary, analyses indicated a significant gambling status by treatment condition interaction effect on ASI-gambling composite change scores. Specifically, participants who had not gambled in the month before initiating treatment showed no change to modest increases in ASI-gambling scores. Because of floor effects, reductions in ASI-gambling scores were not possible in this group. Those with gambling participation before treatment showed no change to modest reductions in ASI-gambling change scores when assigned to standard care conditions but greater reductions in ASI-gambling change scores when assigned to prize CM conditions. Thus, gambling, albeit mild given the low ASI-gambling composite scores overall, decreased significantly in the prize CM conditions relative to SC among cocaine abusers who had wagered in the month prior to starting treatment. These data confirm and extend the safety of prize CM procedures with respect to gambling behaviors.

Although these results are limited by the short timeframe over which gambling was evaluated and the overall low rates of gambling in this sample, these data suggest that prize CM is efficacious in substance abusers who do and those who do not gamble before entering substance abuse treatment. A standardized instrument assessing pathological gambling status was not included in the assessment battery, and no participants reported being “in recovery” from pathological gambling. Thus, data from this study do not speak to the safety or efficacy of prize CM treatments with pathological gambling substance abusers.

Strengths of the study include the large sample size, inclusion of four community-based clinics, and analysis across three studies, all leading to generalization of the findings. Data from this study confirm that prize CM treatments do not increase gambling, and they provide new evidence that prize CM interventions decrease gambling participation relative to standard care among patients who gamble in the month before treatment entry. Thus, prize CM is a safe and efficacious treatment in cocaine abusers who are not in recovery from problem gambling prior to entering treatment.

Acknowledgements

This research and preparation of this report was funded by NIH grants P30-DA023918, R01-DA14618, R01-DA13444, R01-DA018883, R01-DA016855, R01-DA021567, R01-DA022739, R01-DA027615, R01-DA024667, R21-DA021836, P60-AA03510, P50-DA09241, and M01-RR06192.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alessi SM, Hanson T, Tardif M, Petry NM. Low-cost contingency management in community substance abuse treatment settings: A transition to delivering incentives in group therapy. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:293–300. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi SM, Petry NM, Urso J. Contingency management with prize incentives promotes smoking abstinence in residential substance abuse treatment patients. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:617–622. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cummingham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL, Ben-Abdallah A. Problem gambling and comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders among drug users recruited from drug treatment and community settings. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2000;16:347–376. doi: 10.1023/a:1009428122460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Pantalon MV, Potenza MN. Gender differences among recreational gamblers: association with the frequency of alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:145–153. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW, et al. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbin M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein DR, Volberg RA, Toce MT, Harwood H, Johnson RA, Buie T, et al. Gambling Impact and Behavior Study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. National Opinion Research Center; Chicago, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Epstein DH, Schmittner J, Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Preston KL. Randomized trial of prize-based reinforcement density for simultaneous abstinence from cocaine and heroin. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;75:765–774. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GW, Carriero NJ, Takushi RY, Montoya ID, Preston KL, Gorelick DA. Pathological gambling among cocaine-dependent outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1127–1133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, C., Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, Shaffer HJ. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, Petry NM. Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis. 2008;41:517–526. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Downey K. Relationship between problem gambling and substance use in a methadone maintenance population. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. Evaluation of patients treated for pathological gambling in a combined alcohol, substance abuse and pathological gambling treatment unit using the Addiction Severity Index. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1017–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui T, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. The relationship between recreational gambling and substance abuse/dependence: Data from a nationally representative sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, Chen L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health datasets. Annual Review of Public Health. 2002;23:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier J, Heil S, Mongeon J, Badger G, Higgins S. A meta-analysis of voucher- based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasco BJ, vom Eigen KA, Petry NM. Severity of gambling is associated with physical and emotional health in urban primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, et al. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: A National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide for the application of contingency management procedures in standard clinic settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Validity of the Addiction Severity Index in assessing gambling problems. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2003;191:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000071589.20829.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Pathological Gambling: Etiology, Comorbidity and Treatments. American Psychological Association Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Concurrent and predictive validity of the Addiction Severity Index in pathological gamblers. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:272–282. doi: 10.1080/10550490701389849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, Sierra S. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence vs adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006a;74:592–601. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: Contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005b;73:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Ammerman Y, Bohl J, Doersch A, Gay H, Kadden R, Molina C, Steinberg K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006c;74:555–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kolodner KB, Li R, Pierce JM, Roll JR, Stitzer ML, et al. Prize-based contingency management does not increase gambling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006b;83:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Finocche C. Contingency management for group treatment: A demonstration project in an HIV drop-in program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001a;21:80–96. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Stintson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005d;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville B. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: How low can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99:349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Martin B. Reinforcing compliance with non-drug-related activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001b;20:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F. Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: Integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005c;73:354–359. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Roll JM, Cohen A, et al. Effects of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment program: A National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:1148–1156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Roll JM, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Stitzer ML, Pierce JM, Blaine J, Kirby K, McCarty D, Carroll KM. Monitoring serious adverse events in psychosocial treatment trials: Safety or Arbitrary Edits? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:1076–1082. doi: 10.1037/a0013679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Weinstock J, Alessi SM, Lewis MW, Dieckhaus K. Group-based randomized trial of contingencies for health and abstinence in HIV patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:89–97. doi: 10.1037/a0016778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Morasco BJ, Blanco C, Grant BF, Petry NM. Gambling level and psychiatric and medical disorders in older adults: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:301–313. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000239353.40880.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Ghitza UE, Schmittner J, Schroeder JR, Epstein D. Randomized trial comparing two treatment strategies using prize-based reinforcement of abstinence in cocaine and opiate users. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:551–563. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Badger GJ. An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis. 1996;29:495–504. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MA, Kosten TA, Rounsaville BJ. Cocaine abuse and pathological gambling. American Journal on Addictions. 1992;1:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T, Brennan J. Pathological gambling in treatment-seeking substance abusers. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K, Babuscio T, Nich C, Kiluk B, Carroll KM, Petry NM, Rounsaville BJ. Contingency management to reduce substance use in individuals who are homeless with co-occurring psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;33:253–258. doi: 10.1080/00952990601174931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Barnes G, Weiczorek W, Tidwell MC, Parker J. Alcohol and gambling pathology among U.S. Adults: prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:706–712. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J, Canive J, Thuras P, Thompson J, Kim SW, Crosby RD, Garrard J. Mental health of non-gamblers versus “normal” gamblers among American Indian veterans: a community survey. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2008;24:193–205. doi: 10.1007/s10899-007-9084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]