Abstract

Consistent left-right asymmetry requires specific ion currents. We characterize a novel laterality determinant in Xenopus laevis: the ATP-sensitive K+-channel (KATP). Expression of specific dominant-negative mutants of the Xenopus Kir6.1 pore subunit of the KATP channel induced randomization of asymmetric organ positioning. Spatio-temporally controlled loss-of-function experiments revealed that the KATP channel functions asymmetrically in LR patterning during very early cleavage stages, and also symmetrically during the early blastula stages, a period when heretofore largely unknown events transmit LR patterning cues. Blocking KATP channel activity randomizes the expression of the left-sided transcription of Nodal. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that XKir6.1 is localized to basal membranes on the blastocoel roof and cell-cell junctions. A tight junction integrity assay showed that KATP channels are required for proper tight junction function in early Xenopus embryos. We also present evidence that this function may be conserved to the chick, as inhibition of KATP in the primitive streak of chick embryos randomizes the expression of the left-sided gene Sonic hedgehog. We propose a model by which KATP channels control LR patterning via regulation of tight junctions.

Keywords: left-right asymmetry, KATP channels, Kir6.1, tight junctions, Xenopus

Introduction

The large-scale body plan of an organism strongly determines major aspects of its physiology and behavior. Most vertebrates exhibit an external bilateral symmetry that belies a consistently biased internal left-right (LR) asymmetry, and perturbations in normal LR patterning result in defects that can be medically significant (Peeters and Devriendt, 2006; Ramsdell, 2005).

Studies over the last 15 years have begun to reveal the pathways determining laterality in embryonic development (Aw and Levin, 2008; Basu and Brueckner, 2008; Speder et al., 2007; Vandenberg and Levin, 2009). Consistent alignment of internal organs requires an initial chiral element to be oriented with respect to the anterior-posterior and dorso-ventral axes. This information is then transmitted and amplified to the developing organs that undergo asymmetric morphogenesis (Brown and Wolpert, 1990; Levin, 2006). In vertebrates, the downstream steps involve activation of molecules from hedgehog, FGF, EGF-CFC, BMP, and other families (Burdine and Schier, 2000; Levin, 1998), which induce a conserved (Yost, 1999; Yost, 2001) left-specific Nodal signaling (Whitman and Mercola, 2001a; Yost, 2001) gene cascade from the node to the left lateral plate mesoderm (Whitman and Mercola, 2001b). However, the symmetry-breaking steps upstream of asymmetric gene expression are more controversial (Levin and Palmer, 2007; Tabin, 2005).

One model proposes that net unidirectional extracellular fluid flow established by cilia at the node organizer during late gastrulation sets up gradients of morphogens that drive asymmetric gene expression (Basu and Brueckner, 2008; Tabin and Vogan, 2003). On this proposal, the chiral centriole/microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) is amplified into multicellular LR asymmetry by establishing the direction of ciliary motion with respect to the other two axes.

A different model (Levin and Nascone, 1997; Levin and Palmer, 2007) focuses on the role of the centriole/MTOC in biasing intracellular cytoskeletal organization (Danilchik et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2007). The chiral cytoskeleton allows molecular motors (kinesin and dynein) to localize specific cargo to the Left and Right blastomeres. This includes ion channels and pumps whose asymmetric localization sets up differential voltage gradients on the Left and Right sides. This, in turn, establishes asymmetric gene expression (Aw and Levin, 2009; Levin, 2006). Work in chick, frog, sea-urchin, zebrafish, and Ciona have implicated several ion transporters in left-right asymmetry (Adams et al., 2006a; Duboc et al., 2005; Hibino et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2002; Raya et al., 2004; Shimeld and Levin, 2006).

In Xenopus, recent work identified the V-ATPase H+ pump (Adams et al., 2006b), H+/K+-ATPase exchanger (Levin et al., 2002), and the KCNQ1 and Kir4.1 potassium channels (Aw et al., 2008b; Morokuma et al., 2008) as required for LR patterning upstream of left-sided Nodal expression. The resulting endogenous asymmetric changes in ion flux and transmembrane potential operate during early cleavage stages (Adams et al., 2006b; Levin et al., 2002).

Here, we describe the identification of a new player in LR patterning, the ATP-sensitive K+-channel channel (KATP). KATP channels belong to the family of inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channels (Kubo et al., 2005; Nichols, 2006; Noma, 1983; Reimann and Ashcroft, 1999). They are gated by the ratio of ATP:MgADP in the cell, and hence couple the metabolic state of the cell to its membrane potential. When the ATP:MgADP ratio is elevated, KATP channels close causing membrane depolarization, and Ca2+-entry through voltage sensitive Ca2+-channels. Conversely, when the nucleotide ratio is decreased, KATP channels open, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization and cessation of Ca2+-entry. KATP channels are comprised of four pore-forming Kir6.x subunits (either Kir6.1 or Kir6.2), surrounded by four regulatory sulphonylurea receptor subunits (SUR1 or SUR2), which are members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. KATP channels are found in many tissue types, including the pancreatic β-cell (Ashcroft et al., 1984; Findlay et al., 1985), brain (Ashford et al., 1988), and striated and smooth muscle (Spruce et al., 1985; Standen et al., 1989), with different tissues expressing KATP channels with differing physiological properties. The critical roles that KATP channels play have been highlighted by KATP mutations that underlie several important human diseases, including hyperinsulinism, diabetes (Masia et al., 2007; Shimomura, 2009; Sivaprasadarao et al., 2007), heart disease (Bienengraeber et al., 2004; Kane et al., 2005; Miki and Seino, 2005), and hypertension (Chutkow et al., 2002; Kane et al., 2006).

We carried out loss-of-function experiments in Xenopus which demonstrate that KATP is necessary for normal embryonic asymmetry. KATP was required in LR patterning during very early cleavage and also during blastula stages, a developmental period during which very little is known with respect to the LR pathway. We provide evidence that KATP may regulate tight junctions, which are known to be important for correct LR patterning (Brizuela et al., 2001; Simard et al., 2006; Vanhoven et al., 2006). We present functional data that show that this function may be conserved to the chick. Our findings identify a novel role for the KATP channel, and reveal a new molecular component functioning in the time period between early physiological asymmetries (Fukumoto et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2006) and subsequent ciliary flows during neurulation (Schweickert et al., 2007).

Materials and Methods

Animal husbandry

Xenopus embryos were collected according to standard protocols (Sive et al., 2000) in 0.1X Modified Marc's Ringers (MMR) pH 7.8 + 0.1% Gentamicin and staged according to (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967).

Laterality assays

Xenopus embryos at st. 46 were analyzed for position (situs) of 3 organs: the heart, stomach, and gallbladder (Levin and Mercola, 1998a). Heterotaxia was defined as reversal in position of one or more organs. Only embryos with normal dorsoanterior development (DAI=5) were scored in order to avoid scoring instances of secondary randomization due to errors in the DV or AP axial patterning (Danos and Yost, 1996), and only clear left- or right-sided organs were scored. Percent heterotaxia was calculated as number with heterotaxia divided by the number of total scorable embryos, i.e. embryos normal in all other ways, with DAI=5. A χ2 test (with Pearson correction for increased stringency) was used to compare absolute counts of heterotaxic embryos.

Molecular biology

Degenerate PCR of KATP subunits was carried out using standard PCR procedures using Takara Bioscience's KOD HotStart DNA Polymerase. cDNA libraries for RACE PCR were generated from RNAs from stage 10.5, 15 and 25 embryos using Clontech's sMART RACE kit. DNxKir6.1-pore construct was created using standard mutagenesis PCR procedures to mutate the pore loop GFG to AAA. This motif has critical roles in selectivity and pore function (Doyle et al., 1998; Heginbotham et al., 1994; Jiang et al., 2003; Slesinger et al., 1996). DNxKir6.1-ER construct was created by fusing the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-retention motif KHILFRRRRRGFRQ to the C terminus of xKir6.1 (Schwappach et al., 2000). Because channel assembly occurs in the ER, this dominant-negative (DN) construct is expected to assemble with and trap wild-type (WT) subunits in the ER, hence inhibiting their function at the plasma membrane (Ficker et al., 2000). Dominant-negatives against Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 were gifts of Peter Backx (Zobel et al., 2003). DNKir2.3 was a gift of D. Wray (Bannister et al., 1999).

Xenopus microinjection

For microinjections, capped, synthetic mRNAs (Sive et al., 2000), generated using the Ambion mMessage mMachine kit were dissolved in water and injected into embryos in 3% Ficoll using standard methods (100 msec pulses in each injected cell with borosilicate glass needles calibrated for a bubble pressure of 50-60 kPa in water). Each injection delivered between 1-3 nL or 0.5-3 ng of mRNA into the embryo, usually into the middle of the cell in the animal pole, except for the left-right sorting experiments at one cell, in which injections were made off center. 30 minutes post-injection, embryos were washed into 0.5X MMR for 30 minutes, and then cultured in 0.1X MMR until desired stages.

Drug exposure

Our pharmacological screen has been previously described (Adams et al., 2006a; Levin et al., 2002). Xenopus embryos were incubated in pharmacological blockers or openers during the stages of interest depending on the experiment (for the initial drug screen, embryos were incubated from Stage 1 cell to Stage 16, typical doses listed in Supplemental Table 1.), and then transferred to 0.1x MMR and scored for organ reversals at stage 46. Drug dosages were titered to ensure that the dorsoanterior index of the treated embryos was normal (DAI= 5). KATP channel blocker HMR-1098 was a gift from H. Gogelein (Dhein et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2009; Gogelein et al., 2001; Kaab et al., 2003; Light et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2003)) and used at 1.45 mM. In the chick experiments, chick embryos were incubated in the respective drugs from the beginning of incubation to Stage 4+ before being processed for in situ hybridization. Repaglinide was used at a final concentration of 10.6 μM and diazoxide was used at 200 μM.

Immunohistochemistry

Xenopus embryos were fixed for 2 hours at room temperature in MEMFA, transferred to ethanol through a 25%/50%/75% series, and then stored at −20 °C in 100% ethanol. When ready to be sectioned, they were rehydrated, cleared for 2 × 15 minutes in Citrisolv (Fisherbrand), washed once with 50%/50% Citrisolv/paraffin, incubated in 4 changes of paraffin for 30 minutes each, and then embedded in paraffin. 5μm thick sections through paraffin-embedded embryos were made on a manual steel microtome. Sections were mounted onto VWR Superfrost Plus slides by floating on a warm water bath, then dewaxed with Citrisolv and rehydrated.

For immunohistochemical studies, antigens were unmasked by boiling sections in 0.01M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 4 minutes at 60% power in a microwave in plastic coupling jars. Slides were cooled in coupling jars for 30 minutes on the bench top, then washed 3 × 3 minutes in 1X PBS, blocked in 5% goat serum in 1X PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated with the appropriate dilution of primary antibody in blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies anti-Kir6.1 (Alomone Labs), and anti-SUR2 (Pu et al., 2008) were diluted at 1:250, 1:250. Slides were then washed twice for 3 minutes in 1X PBS, and incubated with Alexa 647 secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) at 1:200 dilution in 1X PBS for 1 hour at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Slides were then washed twice for 3 minutes in 1X PBS and mounted using VectorShield Media with a coverslip and analyzed.

Western blotting

Thirty Xenopus embryos were resuspended in 520 μl lysis buffer (1% Triton X100, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris pH 7.6, 2 mM PMSF). Protein solution was mixed at 1:1 with Laemmli sample buffer (Biorad) containing 2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol. The proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane. After washing, the membrane was blocked with 5% dry milk in 1X PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and then incubated overnight in a Mini-PROTEAN II multiscreen apparatus (Biorad) at 4 °C with the primary antibody, diluted in 5% dry milk in PBST (1:2000 for anti-Kir6.1 (Alomone Labs), 1:1000 for anti-SUR2, 1:1000 for anti-c-myc (Sigma)). After washing, the blots were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated second antibody (1:20,000) and developed using Pierce SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Chromogenic in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Harland, 1991). Xenopus embryos were collected and fixed in MEMFA for two hours at room temperature (23°C), washed in PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 and then transferred to ethanol through a 25%/50%/75% series and stored at −20 °C until ready to be processed. Probes for in situ hybridization were generated in vitro from linearized templates using DIG labeling mix from Invitrogen. Chromogenic reaction times were optimized for signal to background ratio.

Detection of KATP channel activity

Measurements of membrane potential in Xenopus laevis embryos were made using sharp electrode impalements in a small (600 μl) Plexiglass recording chamber mounted on the stage of a binocular microscope (SMZ-1, Nikon Instruments). The chamber was constantly perfused by a laminar gravity flow through multiple inlet lines allowing rapid solution changes, connected to a manifold at the inlet to the chamber. The chamber was also connected through Ag/AgCl electrodes in 1% agar bridges to the current-sensing headstage of a voltage clamp amplifier (OC-725C Oocyte Clamp, Warner Instruments) controlled by pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). The exchange rate for the external solution surrounding the embryo was about 95% in less than a minute. Experiments were performed at room temperature (23°C). Intracellular recording electrodes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (TW-150-F4, WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA), filled with 3 M KCl, and had initial resistance of 0.3-1.0 MΩ. Data were digitized on-line and stored on a computer, or were digitized at 2 kHz onto videotape (Neuro-corder DR-890, Neuro-Data Instruments) for off-line analysis. Membrane potentials were recorded in 0.1X MMR, with addition of azide, 250 uM diazoxide (Sigma) or 5μM glibenclamide as indicated (diazoxide and glibenclamide were dissolved as stock solution in DMSO, then diluted to <1% DMSO). A single embryo was simultaneously impaled with two electrodes in separate regions during a typical experiment.

Rubidium efflux assay for KATP channel activity

COSm6 cells were plated at a density of approximately 2.5 × 105 cells per well in 30 mm 6-well tissue culture dishes and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10 mM glucose (DMEM-HG), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The next day, cells were transfected by incubation for 1 hr at 37°C in serum-free DMEM-HG medium containing 2% Fugene-6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN USA), and 400 ng each of combinations of the following cDNAs as described for each experiment: pCDNA-xKir6.1, pCDNA-mKir6.2, pECE-SUR1, pCDNA-DNxKir6.1-pore and pCDNA-DNxKir6.1-ER. Cells were incubated in the presence of the transfection mixture for 12-24 hrs.

For the rubidium flux experiments, 86RbCl (1 mCi/ml) was added in fresh growth medium, 48 hr after transfection. Cells were incubated for an additional 24 hr and then incubated for 10 minutes at 25°C in Krebs-Ringer solution with metabolic inhibitors (2.5 μg/ml oligomycin plus 1 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose). At selected time points, solution was aspirated from the media for counting of 86Rb+ in a scintillation counter, and replaced with fresh solution.

Biotin-labeling assay for tight junction permeability

We used a biotin labeling assay (as described in Merzdorf et al., 1998) to probe tight junction permeability of embryos. Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) is a modified biotin with long 22.4 Åspacer arms making the molecule too large to bypass tight junctions. It contains a highly charged sulfo-group, which prevents it from entering the cell membrane. The biotin group allows it to covalently label primary amines like lysine side chains and N-terminal alpha amines. Hence, only exposed amines on the surface of the embryo will be labeled, and not membranes of inner blastomeres, unless cell-cell tight junction barriers are broken. Just before Stage 7, embryos were placed in 0.1X MMR cooled to 10 °C. Embryos were then transferred to fresh 1mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LCBiotin (Pierce) in 0.1X MMR with 10mM HEPES (pH 7.8), and labeled at 10 °C for 12 minutes. After labeling, embryos were rinsed twice with cooled 0.1X MMR and fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde made fresh from paraformaldehyde in 80mM sodium cacodylate, at room temperature for 1 hour, then dehydrated in ethanol and stored before sectioning and processed for immunohistochemistry with streptavidin-Alexa 555 (Molecular Probes).

Chick whole-mount in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Nieto et al., 1996). Sonic hedgehog probe was as described in (Levin et al., 1995); cKir6.1 probe was as described in (Lu and Halvorsen, 1997).

Image acquisition

Immunofluorescence samples were mounted onto glass slides for viewing, and were imaged using the Semrock CY5-4040A (Ex 628/40-Di 660/18, Em 692/40) cube set on an Olympus BX61 microscope with an ORCA AG digital CCD camera (Hamamatsu) with IPLabs software at approximately 23 °C. Lenses used were: 4X U Plan S-Apo NA=0.16, 10X U Plan S-Apo NA=0.4, 20X U Plan S-Apo NA=0.70, 40X U Plan S-Apo NA=0.90, and 60X Plan Apo Oil NA=1.45.

Results

KATP channel function is necessary for correct LR patterning

To identify ion-dependent signals in left-right (LR) patterning, we carried out a hierarchical pharmacological screen (Adams and Levin, 2006a; Adams and Levin, 2006b). Embryos were incubated in different blockers of ion channels and pumps and then scored for the sidedness of the heart, stomach and gall bladder at Stage 46 (Fig. 1A-E). Only embryos with no other observable abnormalities were scored, in order to rule out secondary effects from toxicity. Embryos in which any of these three organs was reversed were scored as “heterotaxic’. We found that potassium channel blockers, but not sodium, chloride or calcium channel blockers, caused statistically significant rates of heterotaxia. Using inhibitors that distinguish among various families of potassium channels, we then found that 6 blockers of KATP caused heterotaxia (Supplement 1 and Supplemental Table 1).

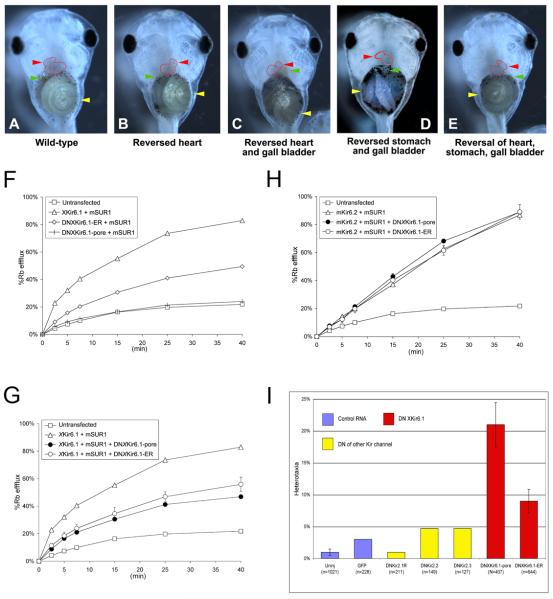

Figure 1. The KATP channel is necessary for correct left-right patterning.

A) Untreated embryo exhibiting normal situs (situs solitus). B-E) Embryos treated with KATP channel blocker HMR-1098 (1.45mM) (Dhein et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2009; Jovanovic and Jovanovic, 2005; Light et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2003) from Stage 1 cell to Stage 16 (then washed out into 0.1x MMR and allowed to develop to Stage 46 before being scored for organ situs) exhibit heterotaxia, including B) reversed heart C) reversed heart and gall bladder D) reversed stomach and gall bladder E) Reversed heart, stomach and gall bladder. F-G) Rubidium flux assays of COSm6 cells expressing various KATP subunits. F) xKir6.1 with mouse SUR1 (mSUR1) dramatically increased the rate of efflux compared to untransfected cells by about four-fold, suggesting the formation of function KATP channels. Expression of DNxKir6.1-pore or DNxKir6.1-ER with mouse SUR1 (mSUR1) show that the ER mutant is able to conduct K+ currents with mSUR1, whilst the pore mutant is non-conductive. G,H) DNxKir6.1-pore and DNxKir6.1-ER knock down activity of KATP channels consisting of WTxKir6.1 and mouse SUR1 (F), but not those consisting of mouse Kir6.2 and mouse SUR1 (G). I) Injection of dominant-negatives against xKir6.1 causes significant levels of heterotaxia, but not injection of GFP, or dominant-negative mRNAs against other Kir channels DNKir2.1 (Zobel et al., 2003), DNKir2.2 (Zobel et al., 2003) and DNKir2.3 (Bannister et al., 1999).

We cloned Xenopus laevis KATP subunit xKir6.1 (Supplement 2) by degenerate PCR. The amino acid sequence of xKir6.1 is highly similar to human and mouse Kir6.1 (93% similar), and related to human/mouse Kir6.2 (84% similar, alignment not shown). To inhibit KATP activity with molecular specificity, we introduced mRNAs coding for dominant-negative (DN) mutants against the pore-forming subunit of the Xenopus KATP channel. DNxKir6.1-pore has a mutation in its pore-loop motif, which acts as a DN when co-expressed with endogenous subunits (Lalli et al., 1998; Tinker et al., 1996; van Bever et al., 2004). DNxKir6.1-ER is a mutant of xKir6.1 fused to an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-retention motif (see Methods). A DN effect of ER-retained mutants on oligomeric complexes has been successfully used in functional studies (Kang et al., 2009; Zerangue et al., 1999).

We ensured that these DNs reduced KATP activity using a Rb+ flux assay, in which Rb+ serves as a surrogate for K+ (Figures 1F-H). Non-transfected COSm6 cells show a low basal rate of K+ efflux (Figure 1F). Expression of DNxKir6.1-pore or DNxKir6.1-ER with mouse SUR1 (mSUR1) show that the ER mutant conducts K+ currents with mSUR1, whilst the pore mutant is non-conductive (Figure 1F). Co-expression of xKir6.1 with mouse SUR1 (mSUR1) dramatically increased the rate of efflux compared to untransfected cells by about four-fold, suggesting the formation of function KATP channels (Figure 1G). Co-expression of either DNxKir6.1-pore or DNxKir6.1-ER with xKir6.1 and mouse SUR1 decreased K+ efflux by about 43% at the 45 min time-point for DNxKir6.1-pore and by about 33% for DNxKir6.1-ER (Figure 1G), suggesting that these constructs indeed act as dominant-negatives against KATP channels formed with xKir6.1 and mouse SUR1. The DNs did not disrupt KATP channels formed with mouse Kir6.2 and SUR1 (Figure 1H), showing that they are specific against KATP channels comprising Kir6.1.

We injected each DN mRNA into one-cell Xenopus embryos, and scored them for LR asymmetry at stage 46. DNxKir6.1-pore and DNxKir6.1-ER both caused statistically significant rates of heterotaxia (21% and 9% respectively, p<0.01), while numerous control injections (dominant-negatives against Kir2.1 (Zobel et al., 2003), Kir2.2 (Zobel et al., 2003) and Kir2.3 (Bannister et al., 1999), and GFP and β-galactosidase mRNA) were without effect (Figure 1I).

Thus, inhibition of the KATP channel via several KATP blockers, and molecular knockdown of xKir6.1 (but not of closely-related Kir channels) via two different DN strategies, both cause significant heterotaxia in Xenopus embryos. We conclude that functional KATP channels are necessary for correct LR patterning in Xenopus.

KATP functions at both early and late cleavage stages in LR patterning

In order to determine when KATP functions in LR patterning, we incubated embryos in the KATP blocker, HMR-1098 (Dhein et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2009; Gogelein, 2000; Gogelein et al., 2001; Kaab et al., 2003; Light et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2003), that caused the highest rate of heterotaxia in our initial screen (Supplement 1), over different time intervals. Embryos were placed into HMR-1098 starting at different times, washed thoroughly at Stage 19, allowed to develop to Stage 46, and then scored for heterotaxia. We found that embryos from different mothers often exhibited significantly different responses in these experiments (Figure 2A), and hence scored embryos from each mother separately.

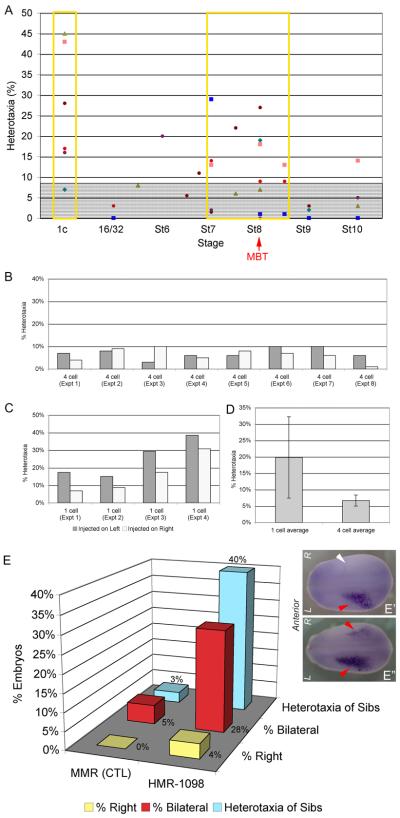

Figure 2. The KATP channel functions in both early and late cleavage in LR patterning, and signals to the left-sided Nodal signaling cascade.

A) Embryos were incubated in KATP channel blocker HMR-1098 starting from the indicated stages, and washed out at ~Stage 19. Each differently-colored dot represents embryos from a different mother. The gray shaded area on the chart indicates 9% heterotaxia, which is the level of heterotaxia required in a dish of 100 embryos to achieve significance of heterotaxia over a dish of controls with 2% heterotaxia in a chi-squared test. Significant rates of heterotaxia were observed when embryos were incubated in HMR-1098 starting from one cell, and from about Stage 7 to Stage 8.5. MBT, mid-blastula transition (see text for details). B) Dominant-negative xKir6.1-pore does not cause significantly different rates of heterotaxia when it is injected on the left versus the right side of the embryo at four cell (difference is not significant, p>0.6 by paired t-test). C) When asymmetric injections were repeated at one cell, it was found that injection on the left gives a consistently higher rate of heterotaxia than injection on the right, and left injected embryos exhibit a consistently higher rate of heterotaxia than right-injected embryos in every experiment (p<0.01 by paired t-test). D) Injections in one half of the embryo at one cell causes approximately 3X as many embryos with heterotaxia as compared to injections in one half of the embryo at four cell, showing that the KATP channel has a role in LR patterning at the earliest cleavage stages. E) KATP channel blocker HMR-1098 randomizes Nodal. Wild-type embryos typically exhibit Nodal expression only on the left side of the embryo (E′). Control embryos incubated in 0.1XMMR media alone exhibited only 4% incorrect Nodal staining (right-sided or bilateral staining), and control sibling embryos exhibited a similar 3% rate of background heterotaxia. However, embryos incubated in HMR-1098 exhibited 33% right-sided (image not shown) and bilateral Nodal staining (E″), compared to the 40% rate of heterotaxia seen in sibling embryos incubated in HMR-1098 (E).

Embryos that were incubated in HMR-1098 blocker starting from either one cell stage or stage 7-8.5 showed significant levels of heterotaxia (Figure 2A). This suggests that KATP functions in LR patterning at both very early cleavage stages, and at a time period just before the mid-blastula transition (stage 7-8), (Newport and Kirschner, 1982a; Newport and Kirschner, 1982b)).

Some components of the laterality pathway function asymmetrically, such that LR patterning defects are only observed when knockdown or overexpression of the gene occurs on one side (Toyoizumi et al., 2005). Hence, we injected embryos with DN mRNA on either the left or right side at 4-cell stage, with -galactosidase (β-gal) mRNA as a lineage tracer to enable retrospective staining and sorting, then scored them for LR patterning defects at stage 46. WT and heterotaxic embryos were then fixed and stained for β-gal to confirm the sidedness of the original injection. We found that embryos injected at 4-cell exhibited the same level of heterotaxia whether they were injected into the left or right sides, suggesting that KATP channel functions bilaterally at later stages (Figure 2B).

We next asked whether the earlier (prior to the 4-cell stage) role of KATP may be unilateral. Since the cleavage and pigment differences that allowed us to distinguish L and R at 4-cell stage were not present at stage 1, embryos were injected at the 1-cell stage, off center, again with (β-gal) mRNA as a lineage tracer to enable retrospective staining and sorting. Because the embryos were injected off-center, they most often received the DN only on one side of the first cleavage plane, which usually divides the embryo into left and right (Klein, 1987; Masho, 1990). Similarly, injection of only one cell at the 2-cell stage is routinely used to target half the embryo, allowing the untreated contralateral half to serve as an internal control (Harvey and Melton, 1988; Vize et al., 1991; Warner et al., 1984). Staining for β-gal and post-sorting allowed us to determine which half received DN mRNA. Strikingly, embryos injected on the left side were consistently and significantly more likely to develop heterotaxia than those that had been injected on the right side (p< 0.01 by paired t-test) (Figure 2C). Thus, we conclude that, in contrast to the later stages, the early period of KATP function is asymmetric, taking place on the left side.

Taken together, the pharmacological and timed injection results suggest that KATP has two separate roles in laterality: a very early, LR asymmetric role, and a later bilateral role.

KATP channel function is upstream of the left-sided Nodal signaling cascade

The left-sided Nodal signaling cascade is a highly conserved step in LR patterning (Boorman and Shimeld, 2002). Hence, we asked whether disruption of KATP activity alters left-sided Nodal expression. Only 5% of control embryos exhibited incorrect Nodal expression (right-sided or bilateral staining; n=57) when assayed by in situ hybridization, comparable to the 3% rate of organ heterotaxia seen in sibling embryos (Figure 2E). In contrast, embryos incubated with HMR-1098 from the one cell stage to Stage 19 exhibited 28% incorrect Nodal staining (non-left-sided expression), and siblings of these HMR-1098 embryos exhibited 40% heterotaxia (n=25; Figure 2E). We conclude that KATP functions upstream of the left-sided transcription of Nodal.

Localization of Kir6.1 protein in LR-relevant developmental stages

In order to gain insight into the function of KATP in LR patterning, we characterized KATP localization in embryos during the relevant stages. To test the specificity of an anti-Kir6.1 antibody, xKir6.1 was fused to a short myc epitope tag (xKir6.1-myc), and injected into one-cell Xenopus embryos. Lysates of injected embryos were collected at Stage 11 (one day later), after allowing the injected mRNA to be translated to detectable levels, and probed with anti-myc (Campbell et al., 1992; Hu et al., 1995) or anti-Kir6.1 (Foster et al., 2008) in Western blotting. Both antibodies recognized the protein product of the injected mRNA, at molecular weights ~60-, ~120-, ~180-kDa and higher (Figure 3A, lanes 2 and 5), indicative of specific multiples of the monomeric band. This suggests that the injected xKir6.1-myc fusion protein was forming multimers, as expected of an oligomeric channel. Therefore, the anti-Kir6.1 antibody, which specifically recognizes a myc- tagged xKir6.1 protein, recognizes xKir6.1. We hence used this antibody to probe endogenous xKir6.1.

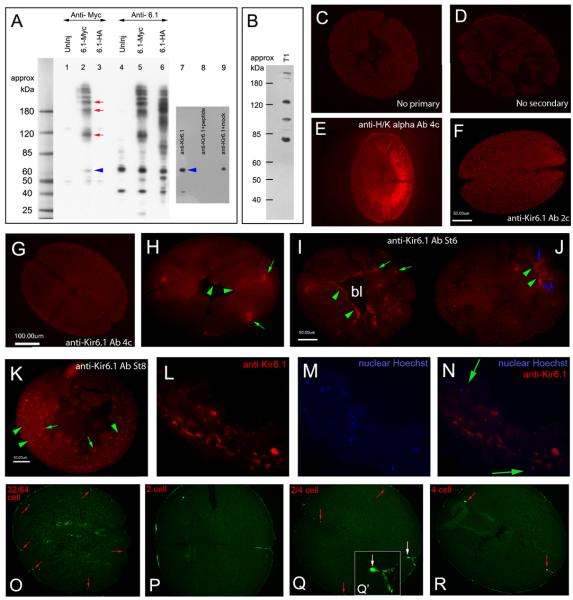

Figure 3. Immunolocalization of Xenopus Kir6.1 and SUR2A.

A) Western blotting with anti-myc and anti-Kir6.1 antibodies against lysates from Stage 11 embryos injected at one cell with xKir6.1-myc mRNA. The blot confirms that both antibodies recognize products with molecular weights at multiples of 60kDa (lanes 2 and 5). Although this is slightly larger than the up to ~51kDa size recognized for Kir6.1 in other studies (Foster et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 1997), it runs at the same size as the Kir6.1-myc construct probed with anti-Myc (blue arrow, lane 2), confirming that the anti-Kir6.1 antibody recognizes xKir6.1 protein. The higher molecular weight bands were not observed in lysates from uninjected embryos (lanes 1 and 4). Lysates of uninjected one-cell Xenopus embryos shows that 1-cell embryos contain maternal xKir6.1 protein (lanes 4 and 7, blue arrow). Pre-incubation of the antibody with Kir6.1 peptide (lane 8), but not with a Kir6.2 peptide (lane 9), abolished immunoreative bands. Anti-myc recognized a faint band at about 45-kDa in uninjected embryos (lane 1); this may be endogenous c-myc. B) A SUR2 antibody recognizes several bands in one cell Xenopus lysates, including a 130 kDa band, approximately the size of SUR2 (150 kDa). C-K) Immunofluorescence with anti-Kir6.1 antibody on sections from early to late cleavage stage in Xenopus embryos. C) Control sections without primary or (D) secondary antibodies exhibit low level staining and low levels of yolk autofluorescence. E) Positive control anti-H/K-ATPase antibody shows expected left-right asymmetric localization. F, G) At two to four cell stage, xKir6.1 exhibits low levels of expression and indistinct localization. H) At Stage 6, xKir6.1 is localized to intracellular domains (green arrows) and to isolated regions on plasma membranes facing the blastocoel (green arrowheads). I, J) At stage 7, Kir6.1 is localized to intracellular domains (I, green arrows) and membranes on the basal face of animal cap cells lining the blastocoel (J, green arrowheads). Intercellular punctate staining is also observed (J, blue arrows). K) At Stage 8, xKir6.1 remains localized to intracellular domains (K, green arrows) and to plasma membrane in many parts of the embryo (K, green arrowheads). L-N) When intracellular domains recognized by anti-Kir6.1 (L) are co-localized with nuclear DNA (M), they appear to lie peripheral to the nucleus (N), suggestive of endoplasmic reticulum localization. O-R) Immunofluorescence with anti-SUR2A antibody in early cleavage Xenopus embryos show punctate, tight junction-like staining at from two cell to stage 32/64 cell. Q′ is a close up of the staining at the junction of a cleaving two to four cell embryo, indicated with a white arrow in Q.

Western blotting with anti-Kir6.1 against uninjected one-cell Xenopus lysates indicated two bands, at ~40- and ~60-kDa (lane 7). (The ~40kDa band is not recognized by anti-myc in xKir6.1-myc-injected embryos, and may be a non-specific band or an xKir6.1 splice variant present in early embryos). The ~60 kDa band is close to the 51 kDa size for Kir6.1 (Foster et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 1997). Importantly, the detected ~60-kDa band ran at about the same size as the ~60-kDa band produced by the overexpressed xKir6.1-myc. The identification of Kir6.1 in 1-cell embryos shows that Kir6.1 maternal protein is present from one cell, consistent with an important role in early developmental patterning. Pre-incubation of the antibody with Kir6.1 peptide (lane 8), but not preincubation with Kir6.2 peptide (lane 9), completely removed observed bands.

A SUR2-specific antibody (Pu et al., 2008) detected several bands in one cell Xenopus lysates, one of which, at about 130kDa, is close to the expected size of SUR2A (150 kDa) and may be a splice variant (Figure 3B).

We carried out immunofluorescence with anti-Kir6.1 and anti-SUR2A, focusing on stages where KATP plays a role in LR patterning. Western blotting showed that xKir6.1 was present from the one cell (Figure 3A, lane 7) stage through at least stage 12 (not shown). However, immunofluorescence on sections of embryos from the 2- to 8-cell stage revealed low levels of signal (Figures 3F,G compare to positive control anti-H/KATPase in Fig. 3E), perhaps due to endogenous yolk autofluorescence. At Stage 6, xKir6.1 begins to localize to intracellular domains (green arrows) and to isolated regions on plasma membranes facing the blastocoel (green arrowheads) (Figure 3H). This pattern continues at stage 7 (Fig. 3I,J), when Kir6.1 localizes to basal membranes surrounding one face of the blastocoel (Figures 3I,J) as well as to punctate bright spots between cells, particularly near the basal surface (Fig. 3J, blue arrows). Colocalization studies (Fig. 3L-N; shown at Stage 8) show that the intracellular domains recognized by anti-Kir6.1 lie peripheral to the nucleus, consistent with ER localization. At Stage 8, xKir6.1 remains localized to intracellular domains (Fig. 3K, green arrows) and to plasma membrane in many parts of the embryo (Fig. 3K, green arrowheads).

Immunofluorescence with anti-SUR2 in early cleavage Xenopus embryos showed punctate, tight junction-like staining during cleavage stages, including at 32/64 cell (Fig. 3O) and two and four cell stages (Fig. 3P-R). Thus, components of KATP are present in early frog embryos with a cellular localization consistent with channel function.

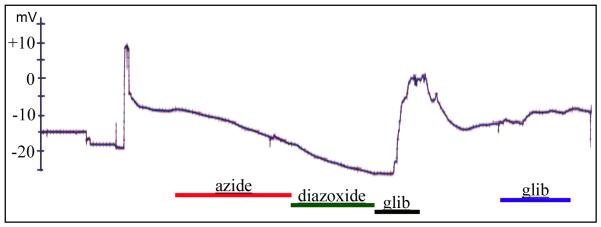

KATP currents can be detected in a subpopulation of Xenopus blastomeres

Because of the known role for voltage gradients in LR patterning, and the control of the membrane potential by KATP in many cell types, we hypothesized that Kir6.1 channels may function in LR by controlling membrane voltage. Sharp electrode voltage measurements in 18 different blastomeres from ten different embryos between the 1-cell stage to St. 6 did not reveal any sensitivity to KATP channel blocker glibenclamide or opener diazoxide (data not shown). However, at about Stage 7, three of twenty blastomeres measured from ten different embryos responded in a manner typical of KATP channels, exhibiting the predicted response to combinations of the treatments diazoxide, azide and glibenclamide, e.g. hyperpolarizing in response to diazoxide, depolarizing in response to glibenclamide and repolarizing upon removal of glibenclamide (Figure 4). This suggests that there are KATP channel currents in early Xenopus embryos. However, this rate of response is uncharacteristically low, suggesting that the channels may lie within inner layers of the embryo, or only within a small domain of cells that may not be electrically coupled to external blastomeres, and hence are undetectable by impalement through external membranes.

Figure 4. KATP channel activity in the early cleavage Xenopus embryo is detectable in a few surface blastomeres.

Whole cell electrophysiological recordings from random locations in developing cleavage stage Xenopus embryos revealed three of 20 blastomeres impaled that responded in a manner typical of KATP channels, exhibiting the predicted response to combinations of the treatments diazoxide, azide and glibenclamide, e.g. hyperpolarizing in response to azide, hyperpolarizing in response to diazoxide, depolarizing in response to glibenclamide and repolarizing upon removal of glibenclamide. Figure 4A shows a representative trace of one of the three responding blastomeres.

KATP channels do not control asymmetry by modulating blastocoel potassium levels

Maintenance of K+ composition in the endolymph by K+-channels is critical for the proper function of the mammalian inner ear (Lang et al., 2007), which uses an H,K-ATPase-Kir4.1-KCNQ1 circuit similar to that found in early frog LR patterning (Aw et al., 2008b; Marcus et al., 2002; Shibata et al., 2006; Van Laer et al., 2006). Because the xKir6.1 potassium channel is localized to basal membranes surrounding the blastocoel during stage 7 (Figure 3I, J), we tested the hypothesis that the KATP channel controls embryonic asymmetry by modulating the potassium currents of the blastocoel.

To determine whether potassium concentration in the blastocoel is important for correct LR patterning, we altered potassium levels in Stage 7 embryos, and assayed LR patterning. We first increased blastocoel potassium by injecting 4 nl of 2.7M potassium gluconate. In an embryo with blastocoel volume of about 100nl, this would raise blastocoel potassium by about 25-fold. This did not cause significant rates of heterotaxia (less than 1%). Conversely, we next decreased blastocoel potassium, by injecting up to 4nl of 2M K+-chelator, Kryptofix 2,2,2. This resulted in a final concentration of chelator in the blastocoel of up to 80 mM, more than sufficient to chelate potassium (Beny and Schaad, 2000; Bussemaker et al., 2002). This also did not cause significant heterotaxia (<1%). Our data suggest that blastocoel potassium concentration is not important for LR patterning, and hence this is unlikely to be a mechanism by which K+ channels function in laterality.

KATP channels regulate tight junctions in Xenopus

A second possible model for KATP function in LR was also suggested by our immunofluorescence studies. Anti-SUR2 showed a punctate, tight junction-like localization (Merzdorf et al., 1998) at 2- to 64-cell cleavage stages (Figure 3O-R). The Kir6.1 antibody also appears to localize to cell-cell junctions and intercellular membranes at about Stage 6 (Figure 3I,J).

The 3 types of cell-cell junctions, tight junctions, adherens/anchoring junctions, and gap junctions, have all been shown to play important roles in LR patterning (Brizuela et al., 2001; Chuang et al., 2007; Garcia-Castro et al., 2000; Kurpios et al., 2008; Levin and Mercola, 1998b; Levin and Mercola, 1999; Simard et al., 2006; Vanhoven et al., 2006). Interestingly, KATP channels co-localize with and control tight junction permeability in organs with regulated tight junctions (Jons et al., 2006).

Hence, we tested the hypothesis that KATP is required for LR asymmetry by regulation of tight junction function in the early embryo. During development, Xenopus embryos exhibit tight junctions from the two cell stage (Merzdorf et al., 1998). We used a biotin labelling assay (Merzdorf et al., 1998) to probe tight junction permeability of cleavage stage embryos that had been injected with KATP channel DN, DNxKir6.1-pore. After incubation of embryos in Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin, a membrane and tight junction impermeant biotin derivative that will only label exposed amines on the embryo surface, embryos were fixed, sectioned and probed with streptavidin-Alexa 555. Embryos were scored as positive for inner membrane staining only if biotin labeling occurred on membranes at least one cell layer deep, as the regular process of cell cleavage of outermost blastomeres during the labeling window may allow biotin to label the second cell layer.

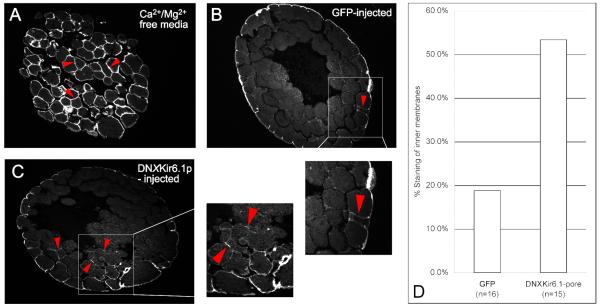

As a positive control, embryos were incubated for 2 hours in Ca2+- and Mg2+- free 0.1X MMR, which breaks tight junctions and induces cell dissociation. 100% of these embryos exhibited extensive staining of inner membranes (Fig. 5A). Negative control embryos injected with GFP mRNA showed faint staining of inner membranes (rarely more than one cell layer deep) in 19% of the embryos (3/16) (Fig. 5B). In contrast, DNx6.1p-injected embryos showed extensive staining of inner membranes, often several cell layers deep, in 53% (8/15) of embryos (Fig. 5C,D).

Figure 5. Dominant-negative DNxKir6.1-pore against the KATP channel changes tight junction properties of early cleavage stage Xenopus embryos.

A tight-junction and membrane impermeable biotin that labels surface proteins allowed probing of tight junction integrity in Xenopus embryos (Merzdorf et al., 1998). A) Incubation of embryos in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free media caused breaking of tight junctions and extensive labeling of inner membranes. B) Control embryos injected with Venus-GFP mRNA showed faint staining of inner membranes, but not more than one cell layer deep (red arrowhead and inset). C) Embryos injected with DNxKir6.1-pore showed extensive staining of inner membranes, often several cell layers deep (red arrowheads and inset). D) In total, 3/16 embryos (19%) injected with control GFP mRNA exhibited staining of membranes one cell layer or more deep, and 8/15 (53%) of embryos injected with DNxKir6.1-pore mRNA exhibited staining of membranes one cell layer or more deep.

These data demonstrate that DNxKir6.1 expression changes the intercellular adhesion properties and/or tight junction integrity of early Xenopus embryos. Since KATP channels have been shown to control tight junctions (Jons et al., 2006), and appropriate functioning of tight junctions is necessary for left-right patterning (Brizuela et al., 2001; Simard et al., 2006; Vanhoven et al., 2006), we propose that KATP disruption randomizes LR asymmetry via changes in the properties of tight junctions in the early embryo.

KATP function in the LR pathway is conserved in chick embryogenesis

Several ion channel and pump proteins have been shown to function in LR patterning in chick embryos (Adams et al., 2006b; Levin et al., 2002; Raya et al., 2004). The chick is an important model species for understanding asymmetry because its blastoderm architecture is typical of most mammals. Hence, we wanted to test whether KATP channel function in LR patterning is conserved to the chick.

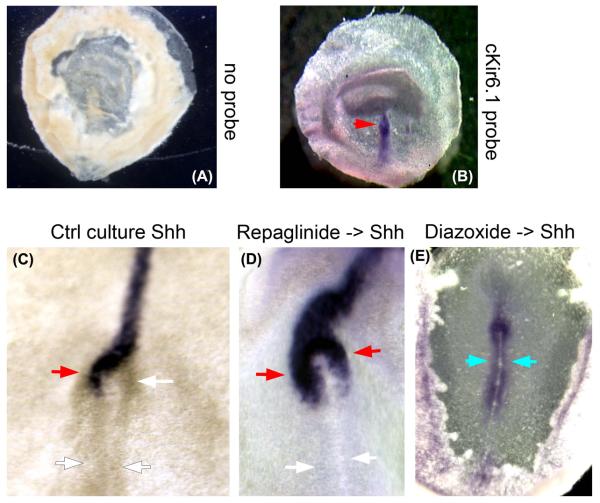

Chick Kir6.1 (cKir6.1) is transcribed throughout the early primitive streak in gastrulating chick embryos in a symmetrical manner, at precisely the time at which differential membrane voltage gradients are establishing asymmetric gene expression (Levin et al., 2002) (Figure 6A,B). In order to test whether KATP function is important for chick LR asymmetry, we analyzed the expression of a key early left-sided gene, Sonic hedgehog (Levin et al., 1995), following bilateral exposure to activators and blockers in ovo from st. 1 to st. 5. Shh is a standard readout in the chick because it is a known determinant of the highly conserved left-sided Nodal domain and subsequent organ situs (Levin et al., 1997; Pagan-Westphal and Tabin, 1998).

Figure 6. KATP function in the LR pathway is conserved in chick embryogenesis.

A, B) Chick Kir6.1 is transcribed throughout the early primitive streak in a symmetrical manner, at the time during which differential membrane voltage gradients are establishing asymmetric gene expression (Levin et al., 2002). C) Control embryos exposed to vehicle alone exhibited 94% left-sided Shh. D) 29% of embryos exposed bilaterally to 10.6 μM KATP blocker repaglinide (Dabrowski et al., 2001; Gromada et al., 1995) exhibited randomized expression of Shh (p<0.01 by chi-squared test). E) Bilateral exposure to 200 μM KATP activator diazoxide (D'Hahan et al., 1999) randomized Shh, also inducing a unique phenotype not known to be observed after any other treatment: expansion of Shh expression posteriorly from the node into the mid-streak.

Whereas embryos exposed to vehicle alone exhibited 94% left-sided Shh (Figure 6C) and only 6% incorrect Shh (right-sided, bilateral or no Shh expression), bilateral exposure to the KATP channel blocker repaglinide (Dabrowski et al., 2001; Gromada et al., 1995) randomized expression of Shh (Figure 6D), such that 29% of embryos exhibited incorrect Shh expression (p<0.01 by chi-squared test). Bilateral exposure to the KATP channel activator diazoxide (D'Hahan et al., 1999) likewise randomized Shh, and also induced expansion of Shh expression posteriorly from the node into the mid-streak (Figure 6E), a unique phenotype not previously described as a consequence of any other known treatment. Thus, the expression of cKir6.1 at the place and time where ionic signaling is being transduced into gene expression changes (Raya et al., 2004), along with the randomization of LR marker Shh following pharmacological treatments targeting KATP channels, are consistent with a role of KATP channels in chick LR patterning.

Discussion

KATP channels are involved in left-right patterning

Upstream of asymmetric gene expression, the left-right (LR) patterning pathway in numerous vertebrate and invertebrate model species involves a variety of physiological signals, including calcium fluxes (Schneider et al., 2007), voltage gradients (Adams et al., 2006b; Levin et al., 2002), and flows of endogenous small molecule signals such as inositol polyphosphates (Albrieux and Villaz, 2000; Sarmah et al., 2005) and neurotransmitters (Fujinaga and Baden, 1991; Toyoizumi et al., 1997), via ion channels and pumps. LR-relevant ion transporters include Ca2+ channels (Garic-Stankovic et al., 2008; Hibino et al., 2006; McGrath et al., 2003; Pennekamp et al., 2002), KCNJ9 (Aw et al., 2008b) and KCNQ1 (Morokuma et al., 2008) potassium channels, as well as pumps, including the ER Ca2+ pump (Kreiling et al., 2008), and H+ pumps (Adams et al., 2006b), H+/K+ exchangers (Levin et al., 2002), and Na+/K+ exchangers (Ellertsdottir et al., 2006).

The hierarchical pharmacological screen that led to the identification and molecular validation of several H+ and K+ transporters in Xenopus laevis (Adams and Levin, 2006a; Adams and Levin, 2006b) also implicated the KATP channel (Supplement 1). This screen, which assays the position of 3 internal organs, has a maximum detectable incidence of randomization of 87% (because fully-randomized organs occasionally land in their correct positions by chance, thus being scored as wild-type). Blocking of KATP caused heterotaxia rates of up to ~50%, comparable to levels seen after knockdown of other proteins involved in LR patterning (Adams et al., 2006a; Hadjantonakis et al., 2008; Kishimoto et al., 2008; Maisonneuve et al., 2009; Morokuma et al., 2008; Yamauchi et al., 2009), suggesting the KATP channel as a component of LR patterning. The range of heterotaxia rates caused by different blocker drugs is likely a function of both drug efficacy (these drugs were developed in mammals and may have differing efficiency against Xenopus KATP channels) as well as solubility in aqueous solution. Interestingly, the drug that causes the highest rate of heterotaxia, HMR-1098, is the most water-soluble of all the KATP drugs used in the screen. Of note, our strict requirement of only analyzing embryos of dorso-anterior index (DAI) = 5 required that we titer all mRNA and blocker reagents to low levels which result in tadpoles with no defects other than randomization. Thus, the penetrance of the observed phenotypes would be significantly higher at higher levels of KATP inhibition.

A similar assay also implicated KATP function in chick (Fig. 6), showing that KATP's function in LR asymmetry is conserved to at least one other vertebrate species. The chick is a particularly important model system for understanding the evolutionary aspects of asymmetry because it develops in a flat blastodisc typical of most mammals. While physiological mechanisms establishing consistent asymmetries prior to the formation of the chick node have begun to be investigated (Levin et al., 2002), our follow-up experiments focused on the frog system because of the greater accessibility of the early Xenopus embryo to electrophysiological experiments. We confirmed the involvement of KATP channel function using gene-specific dominant negative constructs (DNs) (Fig. 1). Unlike morpholinos or interfering RNA (RNAi), which cannot directly affect the function of proteins that are already present, DN mutants function at the protein level by assembling with wildtype subunits and abrogating protein function. Hence, once translated, DNs can probe the role of KATP at the earliest stages of LR, including targeting maternal protein that may not turn over for many cell cycles. This is especially important in light of our findings that maternal xKir6.1 is present from the one cell stage (Figure 3A).

Our DN mutants against xKir6.1 specifically inhibit the activity of KATP channels comprising xKir6.1 (Figure 1G), but not those comprising mouse Kir6.2 (Figure 1H). It is still debated as to whether heteromeric KATP channels consisting of both Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 occur in native tissues (Kono et al., 2000; Pountney et al., 2001; Seharaseyon et al., 2000), and our data suggests that, in our system, Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 do not oligomerize. These xKir6.1 DN mutants cause significant rates of heterotaxia, corroborating the pharmacological data and indicating that KATP – and specifically, KATP channels formed of xKir6.1 - is necessary for LR patterning in Xenopus laevis.

KATP channels are expressed in multiple tissues in adult vertebrates. The Kir6.2 isoform is prominent in striated muscle, pancreatic islet cells and neurons. Loss- or gain-of-function mutations cause congenital hyperinsulinism (Huopio et al., 2002) and diabetes (Gloyn et al., 2004; Koster et al., 2000), respectively. In the latter case, diabetes can also be associated with developmental delay and epilepsy, due to aberrant neuronal activity (Gloyn et al., 2004). The above data demonstrate a novel function for xKir6.1-based KATP channels in development. In mammals, the orthologous Kir6.1 isoform is prominent in smooth muscle, and genetic knockout animals exhibit coronary vasospasm due to the loss of hyperpolarizing currents in the coronary vasculature (Miki and Seino, 2005), but to date, there are no reports of developmental abnormalities in these animals.

When does the KATP channel act in the LR pathway?

By adding the channel inhibitor HMR-1098 at different time points, we probed KATP channel function beginning at different developmental stages without requiring immediate drug wash-out, since the critical differentiating time period is in the beginning of the time interval, not the end. These experiments in Xenopus (Figure 2A) showed that two periods during development appear to be key for the role of KATP in LR patterning—the very early cleavage stages, and a time period just prior to the midblastula transition. This latter time period is particularly interesting, as very little is known about mechanisms of left-right patterning in Xenopus during the stages following physiological activation of ion currents, gap junctions, and serotonergic signaling (Levin, 2006; Levin et al., 2006), but prior to the function of cilia (Schweickert et al., 2007) and asymmetric Nodal transcription (Lohr et al., 1997; Sampath et al., 1997).

In chick, while cleavage-stage mechanisms have not been probed, a post-gastrulation cascade of asymmetric signaling factors is known upstream of asymmetric Nodal transcription (reviewed in (Levin, 1998)). While further characterization will be required to determine whether differential KATP activity is responsible for the different transmembrane potential observed on the L and R sides of the primitive streak (Levin et al., 2002), our data suggest that the role of KATP is upstream of Shh expression at stage 4, and takes place during or prior to other known roles of ion transport in directing subsequent asymmetric gene expression (Figure 6). As with the H,K-ATPase and V-ATPase, the radically different embryonic architecture between the cleavage-stage frog and the chick blastoderm makes it likely that while the function of these transporters are conserved, the precise mechanism by which they establish the LR-relevant gradients may differ (Levin, 2006; Speder et al., 2007). The randomization of Shh expression by global applications of both KATP inhibitors and activators, suggest that differential (asymmetric) activity of KATP channels on the Left and Right sides of the chick embryo is crucial. However, the symmetric expression suggests that this differential activity must arise at the translational level or at the level of gating of mature channel proteins.

The early timing of the first phase of KATP activity in the LR pathway in frog is underscored by our DN experiments, since the rate of heterotaxia (average ~7%) observed in embryos injected at four cell, though statistically significant in our large sample sizes, was much lower than the rate seen in embryos injected at one cell (~ 20%, Fig. 2D), even though in both cases, ~1ng of mRNA was injected into each embryo. Because it takes ~1 hour for injected mRNA to be translated into protein (based on our observations using reporter mRNAs (Aw et al., 2008a)), injection of DN at one cell will result in knockdown of the channel starting from around two to four cell stage. Similarly, injections of the DN at four–cell should result in knockdown starting at about 8-16/32 cell. While the precise profile of mutant protein level vs. time in living embryos is unknown, these data clearly indicate a function for KATP in the LR signaling pathway that is completed during the first few cleavage stages, since equivalent injections at the 4-cell stage are too late to perturb it.

The fact that KATP is necessary for LR patterning at early stages is consistent with our finding that the loss of KATP channel activity leads to randomization of Nodal expression. Thus, the early events controlled by KATP feed into asymmetry through the conserved Nodal-mediated cascade.

How do KATP channels signal to downstream LR pathway components?

A variety of LR patterning molecules exert their effects by unilateral activity. Examples include Sonic hedgehog and Activin (Levin et al., 1995), serotonin (Fukumoto et al., 2005), Zic-3 (Kitaguchi et al., 2000), and Vg1 (Hyatt and Yost, 1998). This is true of the KATP channel at the early period (1-4 cell) of its functioning, since the DNxKir6.1-pore has a greater effect when injected on the left side (Figure 2C). However, other LR pathway components are not asymmetric in their localization; these include gap junctions (Levin and Mercola, 1998b) and syndecans (Kramer et al., 2002). Similarly, the later period of KATP channel activity (Stage 6.5-8) shows no evidence of sidedness in either chicken or Xenopus. This observation is compatible with a role for the KATP channel in regulating tight junctions (see below), as tight junctions occur relatively symmetrically and uniformly around the frog embryo (Merzdorf et al., 1998; Sanders and Dicaprio, 1976).

What is the direct physiological function of KATP in the LR pathway? We used whole-cell electrophysiology to measure KATP currents, and detected channel activity to a limited extent. However, unlike for the H+,K+-ATPase and V-ATPase (Adams et al., 2006b; Levin et al., 2002), consistent asymmetric effects on ion flux or transmembrane potential in early embryos could not be observed. Whole-cell electrophysiology is a very robust assay, and our minimal ability to detect KATP currents was surprising. However, in light of our immunofluorescence results (Figure 3), which show xKir6.1 localized to inner membranes and cell junctions in the embryo, a likely interpretation of our data is that KATP channels in cleavage stage Xenopus embryos lie in domains that may not be electrically coupled to all external blastomeres accessible to microelectrode recordings. Another possibility is that the KATP channel functions in LR asymmetry by a mechanism other than regulation of membrane voltage. Non-ion conducting functions for ion channels have been demonstrated for several channels, including potassium channels (reviewed in (Kaczmarek, 2006)). For example, sodium channel β subunits are themselves cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) that mediate cell adhesion by interacting with other CAMs (Malhotra et al., 2000; McEwen and Isom, 2004).

From our immunofluorescence data and previous work demonstrating KATP regulation of tight junctions (Jons et al., 2006), we hypothesized that KATP channels might regulate tight junction function in Xenopus embryos. Indeed, a biotin assay of tight junction function (Merzdorf et al., 1998) showed that injection of DNxKir6.1-pore alters tight junction integrity in the cleaving embryo, when KATP functions in LR patterning (Figure 5). 53% of embryos exhibited breakage of junctional integrity; although this is lower than the degree of tight junction collapse exhibited by embryos incubated in Ca2+- and Mg2+- free media (100%), the incomplete penetrance is not surprising, as mRNA injections will be more mosaic in nature than incubation in aqueous solution, and mRNA levels are titered down to levels that allow normal overall embryo development, in order to score LR-specific phenotypes. A functional role for KATP channels in inner membranes at tight junctions is consistent with the low detection of KATP channel activity in surface blastomeres (Figure 4), since changes in tight junctions can alter electrical coupling between cells in ways that are not robustly detected at the surface. Also, uniform presence of tight junctions throughout the embryo would explain why KATP expression is not LR-asymmetric at these later stages.

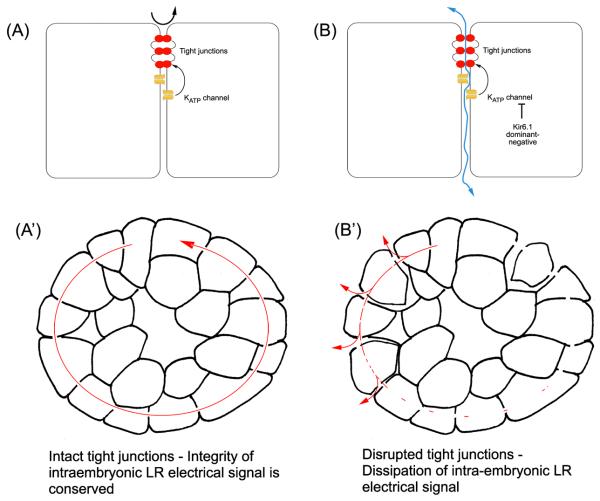

Although this model links KATP to a significant body of work establishing the role of cell junctions in LR asymmetry (Brizuela et al., 2001; Chuang et al., 2007; Garcia-Castro et al., 2000; Kurpios et al., 2008; Levin and Mercola, 1998b; Levin and Mercola, 1999; Simard et al., 2006; Vanhoven et al., 2006), it also raises additional important questions: 1) Why are cell junction proteins important for LR patterning, and 2) How do KATP channels regulate tight junctions?

One model of LR patterning, involving asymmetric morphogen transport across gap junctions down an intra-embryonic electrical gradient (Adams et al., 2006a; Esser et al., 2006), would require functioning tight junctions. Because tight junctions hold cells together, they provide robust support for gap junction contacts to ensure a continuous electrical circuit. Tight junctions also prevent water from the extracellular medium from entering between cells (Fig. 6A), preventing short circuit and leakage of the electrochemical gradient (Fig. 6A′). Breaking of tight junctions (Fig. 6B) would cause dissipation of the potential gradient, hence disrupting the driving force that initiates LR patterning (Fig. 6B′). The role of tight junctions in regulation of the cytoskeleton (Lockwood et al., 2008; Van Itallie et al., 2009) is also intriguing, as the cytoskeleton is critical for the establishment of asymmetries of left-right protein determinants (Aw et al., 2008a; Morokuma et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2005).

How does KATP regulate tight junction integrity? Although several ion channels have been implicated in the regulation of tight junction function (reviewed in (Rajasekaran et al., 2008)), including KATP (Jons et al., 2006), the mechanisms involved remain elusive. Tight junction function is highly regulated by multiple signaling networks (Matter and Balda, 2003). One possibility is that ionic changes could cause alterations in the phosphorylation states of tight junction proteins (Marshall et al., 1999). Another possibility is that conformational changes associated with KATP channel gating could signal to tight junction regulatory molecules (Hegle et al., 2006). It has been shown that overexpression of the tight junction protein claudin alters cell adhesion properties of tight junctions in Xenopus, and induces LR patterning defects in both Xenopus and chick (Brizuela et al., 2001; Simard et al., 2006). Hence, it is possible that disruption of KATP causes an upregulation of claudin that leads to alterations in tight junction function. Finally, although we have shown that dominant-negative xKir6.1 alters the integrity of cell-cell contacts important in left-right patterning, we cannot rule out the possibility that it also exerts effects on other key early processes in LR, including gap junctional communication and serotonin transporter activity.

Conclusions

We have identified a new role for the KATP channel as a component of embryonic left-right patterning. In Xenopus, it acts during a period of time when relatively little is known about laterality determination mechanisms - after the earliest steps that set up differences among L and R blastomeres, but prior to later events such as asymmetric gene expression. This intriguing timing of action suggests that it could link the earliest physiological steps in LR patterning to downstream pathways like the left-sided Nodal signaling cascade. While effects on membrane potential cannot be completely ruled out, it appears to function by exerting effects on tight junction integrity, a property of crucial importance to voltage- and planar cell-polarity-based mechanisms for coordinating cell orientation within the blastoderm. Our experiments in the chick suggest that the role of the biomedically-important KATP in LR patterning may be conserved to other organisms, providing another fascinating example of the same molecular components being used to impose spatial patterning upon embryos of radically different developmental architecture. Future work will address the mechanistic details of tight junction-dependent spread of laterality information during embryogenesis. Understanding the synthesis of the physiological, biophysical, and transcriptional events that reliably pattern the third axis in a world that does not macroscopically distinguish Left from Right will have profound ramifications for developmental, cell, and evolutionary biology as well as biomedicine.

Supplementary Material

We carried out a hierarchical pharmacological screen (Adams and Levin, 2006a; Adams and Levin, 2006b) to identify ion-dependent signals in left-right (LR) patterning. Embryos were incubated in different blockers of ion channels and pumps (a sampling of drugs and respective doses used in this screen is given in Supplemental Table 1) from Stage 1 cell to Stage 16, and then washed out into regular 0.1X MMR media and allowed to develop to Stage 46, before being scored for sidedness of the heart, stomach and gall bladder (Fig. 1A-E). Only embryos with no other observable abnormalities were scored, in order to rule out secondary effects from toxicity. Embryos in which any of these three organs was reversed were scored as “heterotaxic’. Both broad potassium channel blockers and specific blockers again the KATP channel, HMR-1098 but not blockers against sodium, chloride and calcium blockers, caused statistically significant rates of heterotaxia.

Alignment of cloned Xenopus laevis Kir6.1 with Kir6.1 homologues from rat, mouse, rabbit, guinea pig, human, chicken and zebrafish shows high level of amino acid sequence conservation.

Figure 7. A model of how disruption of tight junctions by the KATP channel might cause defects in LR patterning.

A) In a normal embryo, tight junctional integrity is conserved in the presence of functional KATP channels, preventing paracellular flow and leakage (black arrow). A′) In the context of the embryo, functionally robust tight junctional seals would support proper gap junction function and prevent short circuit caused by paracellular leakage, allowing conservation of the intraembryonic LR electrical signal (see text for details). B) The disruption of KATP channels by xKir6.1 dominant-negatives causes loss of tight junctional integrity and hence paracellular leakage (blue arrow), which would alter both transepithelial potentials, and secondarily, transmembrane voltage gradients in the blastomeres. B′) Disruption of tight junctions is predicted to cause rapid dissipation of the intraembryonic LR electrical signal.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ivy Chen and current members of the Levin lab for many useful discussions. We are grateful to Blanche Schwappach, Asipu Sivaprasadarao, and Frances Ashcroft for their expert advice regarding KATP molecular and cell biology. We also thank H. Gögelein for HMR-1098 compound, Peter Backx for DNKir2.1 and DNKir2.2 constructs, and D. Wray for DNKir2.3 construct. ML gratefully acknowledges funding support from the NIH (R01-GM077425) and the American Heart Association (Established Investigator Grant 0740088N); SAW was supported by the A*STAR overseas National Science Scholarship from the Agency for Science and Technology (Singapore); NQS is supported by NIH (HL093626) and the American Heart Association (0630268N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams DS, Levin M. Inverse drug screens: a rapid and inexpensive method for implicating molecular targets. Genesis. 2006a;44:530–40. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams DS, Levin M. Strategies and techniques for investigation of biophysical signals in patterning. In: Whitman M, Sater AK, editors. Analysis of Growth Factor Signaling in Embryos. Taylor and Francis Books; 2006b. pp. 177–262. [Google Scholar]

- Adams DS, Robinson KR, Fukumoto T, Yuan S, Albertson RC, Yelick P, Kuo L, McSweeney M, Levin M. Early, H+-V-ATPase-dependent proton flux is necessary for consistent left-right patterning of non-mammalian vertebrates. Development. 2006a;133:1657–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.02341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams DS, Robinson KR, Fukumoto T, Yuan S, Albertson RC, Yelick P, Kuo L, McSweeney M, Levin M. Early, H+-V-ATPase-dependent proton flux is necessary for consistent left-right patterning of non-mammalian vertebrates. Development. 2006b;133:1657–1671. doi: 10.1242/dev.02341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrieux M, Villaz M. Bilateral asymmetry of the inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium signaling in two-cell ascidian embryos. Biology of the Cell. 2000;92:277–84. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(00)01066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Harrison DE, Ashcroft SJ. Glucose induces closure of single potassium channels in isolated rat pancreatic beta-cells. Nature. 1984;312:446–8. doi: 10.1038/312446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford ML, Sturgess NC, Trout NJ, Gardner NJ, Hales CN. Adenosine-5′-triphosphate-sensitive ion channels in neonatal rat cultured central neurones. Pflugers Arch. 1988;412:297–304. doi: 10.1007/BF00582512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw S, Adams DS, Qiu D, Levin M. H,K-ATPase protein localization and Kir4.1 function reveal concordance of three axes during early determination of left-right asymmetry. Mech Dev. 2008a;125:353–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw S, Adams DS, Qiu D, Levin M. H,K-ATPase protein localization and Kir4.1 function reveal concordance of three axes during early determination of left-right asymmetry. Mech Dev. 2008b;125:353–372. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw S, Levin M. What's left in asymmetry? Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3453–3463. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw S, Levin M. Is left-right asymmetry a form of planar cell polarity? Development. 2009;136:355–66. doi: 10.1242/dev.015974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Young BA, Sivaprasadarao A, Wray D. Conserved extracellular cysteine residues in the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir2.3 are required for function but not expression in the membrane. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:393–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu B, Brueckner M. Cilia: multifunctional organelles at the center of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:151–74. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beny JL, Schaad O. An evaluation of potassium ions as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:965–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienengraeber M, Olson TM, Selivanov VA, Kathmann EC, O'Cochlain F, Gao F, Karger AB, Ballew JD, Hodgson DM, Zingman LV, Pang YP, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. ABCC9 mutations identified in human dilated cardiomyopathy disrupt catalytic KATP channel gating. Nat Genet. 2004;36:382–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorman CJ, Shimeld SM. The evolution of left-right asymmetry in chordates. Bioessays. 2002;24:1004–11. doi: 10.1002/bies.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizuela BJ, Wessely O, De Robertis EM. Overexpression of the Xenopus tight-junction protein claudin causes randomization of the left-right body axis. Dev Biol. 2001;230:217–29. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NA, Wolpert L. The development of handedness in left/right asymmetry. Development. 1990;109:1–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdine R, Schier A. Conserved and divergent mechanisms in left-right axis formation. Genes & Development. 2000;14:763–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussemaker E, Wallner C, Fisslthaler B, Fleming I. The Na-K-ATPase is a target for an EDHF displaying characteristics similar to potassium ions in the porcine renal interlobar artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:647–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AM, Kessler PD, Fambrough DM. The alternative carboxyl termini of avian cardiac and brain sarcoplasmic reticulum/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases are on opposite sides of the membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9321–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CF, Vanhoven MK, Fetter RD, Verselis VK, Bargmann CI. An innexin-dependent cell network establishes left-right neuronal asymmetry in C. elegans. Cell. 2007;129:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutkow WA, Pu J, Wheeler MT, Wada T, Makielski JC, Burant CF, McNally EM. Episodic coronary artery vasospasm and hypertension develop in the absence of Sur2 K(ATP) channels. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:203–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI15672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Hahan N, Moreau C, Prost AL, Jacquet H, Alekseev AE, Terzic A, Vivaudou M. Pharmacological plasticity of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels toward diazoxide revealed by ADP; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 1999. pp. 12162–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski M, Wahl P, Holmes WE, Ashcroft FM. Effect of repaglinide on cloned beta cell, cardiac and smooth muscle types of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Diabetologia. 2001;44:747–56. doi: 10.1007/s001250051684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchik MV, Brown EE, Riegert K. Intrinsic chiral properties of the Xenopus egg cortex: an early indicator of left-right asymmetry? Development. 2006;133:4517–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.02642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danos MC, Yost HJ. Role of notochord in specification of cardiac left-right orientation in zebrafish and Xenopus. Developmental Biology. 1996;177:96–103. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhein S, Pejman P, Krusemann K. Effects of the I(K.ATP) blockers glibenclamide and HMR1883 on cardiac electrophysiology during ischemia and reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:273–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc V, Rottinger E, Lapraz F, Besnardeau L, Lepage T. Left-right asymmetry in the sea urchin embryo is regulated by nodal signaling on the right side. Dev Cell. 2005;9:147–58. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AG, Rees ML, Gioscia RA, Zachman DK, Lynch JM, Browder JC, Chicco AJ, Moore RL. PKC-permitted elevation of sarcolemmal KATP concentration may explain female-specific resistance to myocardial infarction. J Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellertsdottir E, Ganz J, Durr K, Loges N, Biemar F, Seifert F, Ettl AK, Kramer-Zucker AK, Nitschke R, Driever W. A mutation in the zebrafish Na,K-ATPase subunit atp1a1a.1 provides genetic evidence that the sodium potassium pump contributes to left-right asymmetry downstream or in parallel to nodal flow. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1794–808. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser AT, Smith KC, Weaver JC, Levin M. Mathematical model of morphogen electrophoresis through gap junctions. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2144–59. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker E, Dennis AT, Obejero-Paz CA, Castaldo P, Taglialatela M, Brown AM. Retention in the endoplasmic reticulum as a mechanism of dominant-negative current suppression in human long QT syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2327–37. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay I, Dunne MJ, Petersen OH. ATP-sensitive inward rectifier and voltage- and calcium-activated K+ channels in cultured pancreatic islet cells. J Membr Biol. 1985;88:165–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01868430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DB, Rucker JJ, Marban E. Is Kir6.1 a subunit of mitoK(ATP)? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:649–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinaga M, Baden JM. Evidence for an adrenergic mechanism in the control of body asymmetry. Dev Biol. 1991;143:203–205. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90067-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto T, Kema IP, Levin M. Serotonin signaling is a very early step in patterning of the left-right axis in chick and frog embryos. Curr Biol. 2005;15:794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro MI, Vielmetter E, Bronner-Fraser M. N-Cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule involved in establishment of embryonic left-right asymmetry. Science. 2000;288:1047–51. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garic-Stankovic A, Hernandez M, Flentke GR, Zile MH, Smith SM. A ryanodine receptor-dependent Cai2+ asymmetry at Hensen's node mediates avian lateral identity. Development. 2008 doi: 10.1242/dev.018861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL, Pearson ER, Antcliff JF, Proks P, Bruining GJ, Slingerland AS, Howard N, Srinivasan S, Silva JM, Molnes J, Edghill EL, Frayling TM, Temple IK, Mackay D, Shield JP, Sumnik Z, van Rhijn A, Wales JK, Clark P, Gorman S, Aisenberg J, Ellard S, Njolstad PR, Ashcroft FM, Hattersley AT. Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1838–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogelein H, Englert H, Kotzan A, Hack, Rudiger, Lehr K-H, Seiz W, Becker RHA, Sultan E, Scholkens BA, Busch AE. HMR 1098: An Inhibitor of Cardiac ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channels. Cardiovascular Drug Reviews. 2000;18:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gogelein H, Ruetten H, Albus U, Englert HC, Busch AE. Effects of the cardioselective KATP channel blocker HMR 1098 on cardiac function in isolated perfused working rat hearts and in anesthetized rats during ischemia and reperfusion. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s002100000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]