Abstract

siRNA mediated transcriptional knockdown of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), alone or in combination, inhibits uPAR and/or MMP-9 expression and induces apoptosis in the human glioblastoma xenograft cell lines 4910 and 5310. siRNA against uPAR (pU-Si), MMP-9 (pM-Si), or both (pUM-Si) induced apoptosis and was associated with the cleavage of caspases-8, -3 and PARP. Furthermore, protein levels of the Fas receptor (APO-1/CD-95) were increased following transcriptional inactivation of uPAR and/or MMP-9. In addition, Fas siRNA against the Fas death receptor blocked apoptosis induced by pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si, thereby indicating the role for Fas signaling in pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si-mediated apoptotic cell death of human glioma xenograft cells. Thus, transcriptional inactivation of uPAR and/or MMP-9 enhanced localization of Fas death receptor, Fas-associated death domain-containing protein (FADD), and procaspase-8 into lipid rafts. Additionally, disruption of lipid rafts with methyl beta cyclodextrin (MβCD) prevented Fas clustering and pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si-induced apoptosis, which is indicative of co-clustering of Fas death receptor into lipid rafts in glioblastoma xenograft cells lines 4910 and 5310. These data indicate the crucial role of the clusters of apoptotic signaling molecule-enriched rafts in programmed cell death, acting as concentrators of death receptors and downstream signaling molecules, and as the linchpin from which a potent death signal is launched in uPAR and/or MMP-9 down regulated cells.

Keywords: uPAR, MMP-9, siRNA, Lipid raft, apoptosis, Fas

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary tumor in the central nervous system in adults and is also one of the most difficult tumors to treat effectively. Unfortunately, despite the technological advances in imaging, improvements in surgical techniques, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the prognosis of patients with the most common invasive and metastatic tumors remains poor (1). Tumor cells acquire these invasive and metastatic characteristics mainly due to their ability to produce and activate proteolytic enzymes, such as serine, metallo- and cysteine proteases, which are able to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components and breakdown other natural barriers to tumor invasion and metastasize (2). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) belong to a family of zinc-containing extracellular endopeptidases that selectively degrade components of the extracellular matrix, such as proteoglycans, laminin, and fibronectin (3). In cancer patients, MMPs also play an important role in disease progression and their activities are reported to associate with tumor promotion, angiogenesis and invasion (4, 5). The serine protease, urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and its receptor (uPAR), are believed to play an important role in migration, cellular adhesion, differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis and this signaling requires direct interactions of uPAR with a variety of extracellular proteins and membrane receptors (6). Association of uPA with its receptor, uPAR, provides an inducible, transient, and localized cell surface proteolytic activity (7, 8) which is recognized as a major factor in tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Previous evidence indicates that converging cascade activated by the urokinase- type plasminogen activator/plasmin system and MMP-3 enhances MMP-9 activation and tumor cell invasion (9). Therefore, both MMPs and uPAR represent very potent therapeutic targets. In the present study, we investigated the effects of siRNA mediated targeting of uPAR and MMP-9 in glioma xenograft cells as both these molecules have been reported to contribute to glioma progression (2).

Lipid rafts are liquid-ordered membrane microdomains, enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol, which are thought to function as platforms for signal transduction by selectively compartmentalizing receptors and signaling effectors (10). Characteristically, proteins associated with lipid rafts are insoluble in the non-ionic detergent Triton X-100 and can be distinguished from the detergent-insoluble cytoskeleton by their low density on sucrose gradients. Both uPAR and MMP-9 are known lipid raft proteins (10,11). Fas is a major member of the death receptor family, a subgroup of the tumor necrosis factor receptor super family, characterized by a cytoplasmic death domain that is responsible for the transmission of apoptotic signaling through interaction with death domain-bearing adaptor molecules (12). Because lipid rafts have been found to be essential for the initiation of Fas-mediated cell death signaling, it is thought that Fas-mediated apoptosis is triggered by its localization and clustering in membrane rafts (10, 13-17). Stimulation of Fas results in receptor oligomerization and recruitment of the adaptor molecule, Fas-associated death domain-containing protein (FADD), through interaction between its own death domain and the clustered receptor death domains. In turn, FADD recruits procaspase-8 via a death effector domain interaction forming the so-called death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) and leading to apoptosis (18).

RNA interference (RNAi) is a specific and efficient gene silencing mechanism, which takes place at a post-transcriptional level. In the present study, we used a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-promoter driven plasmid construct in order to deliver small interfering RNA molecules that target mRNA of uPAR and/or MMP-9. We also demonstrated that uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibition induced caspases-9 mediated apoptosis in SNB19, glioblastoma cell lines (19). However, as most established cell lines do not exactly mimic the in vivo behavior of human glioma, we performed experiments using two human xenograft cell lines 4910 and 5310, derived from human tissues and maintained in mice. These cell lines displayed a close resemblance to respective patient tumors (20). In the present study we sought to determine the mechanisms underlying the induction of apoptosis in uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibited cells. Here, we show that uPAR and/or MMP-9 downregulation in the xenograft cells leads to apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. We also show that cell death is mediated by the clustering of Fas into lipid rafts, and demonstrate that disruption of lipid raft inhibited the initiation of apoptosis in uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibited cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Reagents

4910 and 5310 xenograft cell lines (kindly provided by Dr. David James, University of California at San Francisco), were generated and maintained in mice and are highly invasive in the mouse brain (20). At the 3rd or 4th passage of xenograft cells from mice heterotopic tumors were frozen and these frozen stocks were used for further experimental studies up to the 10th passage to obtain consistent results. Xenograft cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Inc., Frederick, MD). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. We used the following antibodies in this study: anti-MMP-9, anti-uPAR, anti-Fas, anti-Fas-L, anti-FADD, anti-CD71 (Transferrin receptor), anti-α-tubulin, anti-Flotillin-1, anti-Flotillin-2, (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Caspase-3, anti-Caspase-8, anti-active-caspase-8 (Cell Signal Technology, Boston, MA), anti-PARP (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), anti-GAPDH (Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton, CO). HRP conjugated and Alexa fluor 488, Alexa fluor 595 secondary antibodies and Fas siRNA (siRNA sequences for Fas siRNA 5′GAAGCGUAUGACACAUUGAtt3′ and UCAAUGUGUCAUACGCUUCtt 3′, 5′CCCAAACAUGGAAAUAUCAtt3′ and 5′ UGAUAUUUCCAUGUUUGGGtt 3′, and 5′GAACCCAUGUUUGCAAUCAtt3′ and 5′ UGAUUGCAAACAUGGGUUCtt 3′; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were also used in this study. The other materials used in this study were Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), DAB peroxidase substrate, methyl beta cyclodextrin (MβCD), Caveolae /Raft isolation kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), Caspase-8 inhibitor (IETD-FMK; Millipore, Billerica, MA), ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), MTT cell growth assay kit (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA).

Construction of plasmids and transfection

A pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) plasmid with a CMV promoter was used to construct the siRNA-expressing vector. The siRNA constructs for uPAR (pU-Si), MMP-9 (pM-Si) and a bicistronic for both of them (pUM-Si) were prepared as described previously (19). Non-specific siRNA expressing vector, Control-siRNA (pControl-Si) was constructed using the following sequence: 5′-GCACGGAGGTTGCAAAGAATAATCGATTATTCTTTGCAACCTCCGTGC-3′. 4910 and 5310 xenograft cells were transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si using Gene Expresso™ DNA in vitro transfection reagent (Lab Supply Mall, Gaithersburg, MD) as per the manufacturer's instructions. For overexpression of uPAR or MMP-9, cells were transiently transfected 24 hrs before siRNA transfection with expression vector containing the human uPAR or MMP-9 open reading frame.

Gelatin Zymography

For preparation of tumor conditioned medium, the medium was removed from 4910 and 5310 cells after 48 hrs of transfection, washed with PBS; 3 ml of serum-free medium was added and incubated for overnight. MMP-9 gelatinolytic activity in conditioned medium was determined by gelatin zymography as described previously (21). Briefly, conditioned medium containing equal amounts of protein were resolved over gelatin-SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The gels were washed with 2.5% Triton X-100 to remove SDS followed by overnight incubation at 37°C in Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer. The gel was stained with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue in 10% acetic acid and 10% isopropanol and subsequently de-stained. Gelatinolytic activities were identified as clear zones of lyses against a blue background.

Immunoblotting

4910 and 5310 cells were transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si for 60 hrs. Whole cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in RIPA lysis buffer with 1 mM sodium orthovenadate, 0.5 mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and 10 μg/mL leupeptin as described previously (21). Equal amounts of protein was resolved over SDS-PAGE (6-15% gels) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Proteins were detected with primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Comparable loading of proteins on the gel was verified by re-probing the blots with an antibody specific for the housekeeping gene product GAPDH.

Semi-quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIZOL reagent as per the manufacturer's instructions. For the synthesis of first strand cDNA, we used 2 μg of total RNA and poly-dT primers, and a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Tor amplify this cDNA and determine the mRNA transcript level, PCR reaction was performed using the following primers: MMP-9: 5′-TGGACGATGCCTGCAACGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCGTGCGTGTCCAAAGGCA-3′ (reverse); uPAR: 5′-TTACCTCGAATGCATTTCCT-3′ (forward) and 5′- TTGCACAGCCTCTTACCATA -3′ (reverse); and GAPDH: 5′-GGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCTTCACCACCATG GAGAAGGCT-3′ (reverse). PCR products were resolved over 2% agarose gels, visualized, and photographed under ultraviolet light.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using a modified MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay as a measurement of mitochondrial metabolic activity. Cells were seeded on 96-well cell culture plates at 100 μL/well (2 × 103 cells/well) and incubated overnight. Next, cells were transfected as described above with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si and incubated at 37°C. After 12 to 96 hrs, MTT reagent was added and cells were incubated for 4 hrs at 37°C. The rate of absorbance of formazan, which is a dye produced by live cells, was measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) at 550 nm. The percent of cell viability was calculated as the ratio of absorbance of treated cells at 550 nm to absorbance of control cells at 550 nm × 100.

Lipid raft isolation

Lipid rafts were isolated from cells using a caveolae/rafts isolation kit as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 60 hrs after siRNA transfection, CTxB-HRP solution was added, cells were kept on ice for 1 hr and washed with ice cold PBS. Cells were lysed in 1 mL of Triton-X-100 containing lysis buffer and fractionated by gradient centrifugation using OptiPrep gradient medium (35%, 30%, 25% 20% and 0% from bottom to top). Ten fractions (~1 mL each) were collected from the top of the gradient. To determine the location of lipid rafts in the discontinuous OptiPrep gradient, 2 μL of the individual fractions were subjected to dot blot analysis for location of GM1-containing lipid rafts (CTxB-HRP binding). Fractions positive for GM1 (fractions 2-4) were pooled and 30 μL of the pooled fractions were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and processed as described in the immunoblotting section.

Cholesterol depletion

After 36 hrs of transfection, cells were washed in serum-free medium and pretreated with 2.5 mg/mL MβCD for 30 min at 37°C in serum-free medium. Cells were then washed three times with PBS, complete culture medium added, and cells incubated for a further 24 hrs. Either cells were processed for TUNEL analysis or cell lysates were processed for immunoblotting as described in appropriate sections.

Orthotopic animal models

4910 and 5310 xenograft glioblastoma cells (2 × 105) were injected intracerebrally into nude mice as previously described (22). Tumors were allowed to grow for 10-12 days, and animals were separated into groups (six animals per group). ALZET osmotic pumps (model 2004, ALZET Osmotic Pumps, Cupertino, CA) were implanted for plasmid delivery (dose: 3-6 mg/kg body weight) as described previously (23). After 6 weeks or when the control animals started showing symptoms, animals were euthanized. The brains were collected and fixed in buffered formaldehyde. To visualize tumor cells and to examine tumor volume, the brain sections were stained with hematoxilin and eosin (H&E).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

We checked for apoptosis in orthotopic tumor sections of siRNA-treated mice and 4910 and 5310 cells treated with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si as described previously (24). Briefly, 5 × 103 cells were plated in 8-well chamber slides and transfected with plasmids as described above. After 60 hrs, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature, and permeabilized on ice in 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 0.1% sodium citrate in PBS for 2 min (for cells) or 8 min (for tissue sections). To determine the number of apoptotic cells in the tissue sections, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Samples were then incubated in TUNEL reaction mixture in a dark humidified atmosphere for 1 hr at 37°C and washed with PBS. 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining mounting solution was used for nuclear counterstaining. Samples were imaged with an Olympus BX-60 research fluorescence microscope attached with a CCD camera. The apoptotic index was defined as follows: apoptotic index (%) = 100 × (apoptotic cells/total cells).

Immunofluorescent and immunohistochemical analyses

4910 and 5310 cells (5 × 103) were cultured in chamber slides and transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si for 60 hrs. For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated on a shaker with anti-Fas antibody (1:100 dilutions) for 1 hr at 4°C. Samples were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 hr with Alexa fluor-488-conjugated secondary antibody. Next, samples were washed with PBS and stained with 8 mg/mL Alexa fluor-595-CTxB subunit as a raft marker. Samples were then analyzed using a confocal microscope. Co-localization assays were analyzed by excitation of the corresponding fluorochromes in the same section. Negative controls, using a mouse IgG, showed no staining.

For immunohistochemical analysis, tissue sections (4-5 μm-thick) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, washed with PBS, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton-X-100, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies for uPAR, MMP-9, Fas or active caspase-8 as described previously (24). Tissue sections were then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB peroxidase substrate; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution, counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted. The images were captured with an Olympus BX-60 fluorescent microscope attached with a CCD camera.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error (S.E.) of at least three independent experiments, which were each performed at least in triplicate. Results were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t-test to assess statistical significance. Statistical differences are presented at probability levels of p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001.

RESULTS

siRNA against uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibits respective proteins at transcription level in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells

We first examined the effect of plasmid mediated expression of siRNA constructs for uPAR (pU-Si) and MMP-9 (pM-Si) alone and in combination (pUM-Si) on protein and mRNA expression levels in 4910 and 5310 glioblastoma xenograft cells. Cells were transfected with mock (PBS), control-siRNA (pControl-Si) and the above mentioned constructs. MMP-9 protein that secreted into the conditioned medium was examined using gelatin zymography. MMP-9 gelatinolytic activity was higher in cells transfected with mock and pControl-Si. The gelatinolytic activity of MMP-9 was reduced in cells treated with siRNA against MMP-9 alone and in combination as compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected cells (Fig. 1A). However, there was not much change in the levels of MMP-2 gelatinolytic activity in 4910 and 5310 cells after transfection with these constructs. To support these results, we performed immunoblot analyses using anti-MMP-9 antibody. MMP-9 protein levels were decreased by more than 75% in cells transfected with pM-Si and pUM-Si compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected cells as quantified by densitometric analysis (Figs. 1A-B). Similarly, uPAR expression was decreased by ~80% in cells transfected with pU-Si and pUM-Si when compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected cells (Figs. 1A-B). To determine whether decreased levels of uPAR and MMP-9 were caused by gene transcription, we examined the mRNA transcript levels of uPAR and MMP-9 using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in figures 1A-B, uPAR and MMP-9 mRNA transcript levels were decreased in cells transfected with pU-Si and pM-Si respectively and also in pUM-Si transfected cells by more than 80 % (p<0.01; pUM vs pControl-Si ).

Figure 1. siRNA against uPAR and/or MMP-9 induces transcriptional inactivation of uPAR and/or MMP-9 in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells.

4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells were transfected as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells were transfected with mock, control siRNA (pControl-Si), pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si. The medium was aspirated after 48 hrs of incubation, 3 mL of serum-free medium was added, and cells were incubated overnight. (A) Top: Gelatin zymographic analysis for secreted MMP-9 activity in the tumor conditioned medium. The experiments were repeated three times and a representative zymogram is shown. Middle: Immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates for uPAR and MMP-9 expression in cell lysates, which were prepared 60 hrs after siRNA transfection. The experiments were repeated three times and a representative blot is shown. The blot was stripped and re-probed with GAPDH antibody as a loading control. Bottom: Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis for uPAR and MMP-9 mRNA transcripts in mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si and pM-Si-transfected cells. Total RNA was extracted from transfected cells and cDNA was synthesized as described in Materials and Methods. The PCR reaction was set up using the first-stand cDNA as the template for uPAR and MMP-9. PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels. GAPDH served as a control. (B) Top: Protein band intensities were quantified by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The levels of uPAR and MMP-9 protein were normalized to protein levels in mock-transfected cells. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.01, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected control cells. Bottom: Amplified DNA band intensities were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The levels of uPAR and MMP-9 mRNA transcripts were normalized to the mock-transfected cells product. GAPDH served as a control. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.01, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected cells. (C) The effect of siRNA against uPAR and/or MMP-9 on 4910 and 5310 glioblastoma xenograft cell viability was determined by MTT assay. 4910 and 5310 cells were transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si. After 12 to 96 hrs of incubation, MTT reagent was added and cells were incubated for another 4 hrs at 37°C. The absorbance of formazan in DMSO was measured with a microplate reader at a wavelength of 550 nm. The percent of viability was calculated as a ratio of mean absorbance of sample to mean absorbance of control-siRNA × 100. Points: mean of three experiments; bars: SE.

uPAR and/or MMP-9 siRNA decreases cell viability in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells

siRNA against either uPAR or MMP-9, alone or in combination, decreased cell viability in 4910 and 5310 cells compared to mock and control-siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 1C). Transfection with pU-Si and pM-Si decreased viable cells by ~35% in individual siRNA (pU-Si or pM-Si) treated cells and up to 50% in pUM-transfected cells when compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected cells at 48 hrs. Notably, we observed a 75-80% decrease in cell viability in pUM-Si-transfected cells as compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected cells at 96 hrs (Fig. 1C).

Transcriptional inactivation of uPAR and/or MMP-9 induces apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells

uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition displayed morphological signs of apoptosis, including cell shrinkage and eventual disintegration into numerous apoptotic bodies within 60 hrs of treatment (data not shown) in glioma xenograft cells. These observations suggest that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition can induce apoptosis in these cell lines. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the effect of uPAR and/or MMP-9-siRNA on the induction of apoptosis in the glioblastoma xenograft cell lines 4910 and 5310 (Figs. 2A-C). TUNEL analysis indicated that inhibition of either uPAR or MMP-9, alone induced apoptosis in about 35 % of the cells. However, the percentages of apoptotic cells after simultaneous inhibition of uPAR and MMP-9 increased up to ~65% as compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected controls in both, 4910 and 5310 cells (Figs. 2A-B). To confirm this apoptotic response, we performed immunoblot analysis using anti-caspase-3 and -8, and anti-PARP antibodies. uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition resulted in cleavage of caspase-8 followed by caspase-3, with subsequent cleavage of 116 kDa PARP to an 85 kDa (Fig. 2C). To further confirm the role of uPAR & MMP-9 inhibition in the induction of apoptosis, we overexpressed uPAR and/or MMP-9 in cells transfected with pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si. Figures 3A and B indicate that transfection with uPAR and MMP-9 cDNA restored uPAR and MMP-9 levels to that of the controls. Accordingly, restoring uPAR and MMP-9 expression in pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si transfected cells prevented uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptosis as determined by TUNEL analysis (Fig. 3B).

Figure 2. siRNA against uPAR and/or MMP-9 induces apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells.

4910 and 5310 cells were plated and transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si and incubated for 60 hrs. (A) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) enzyme assay (Insets: negative control). (B) Quantification of apoptotic cells. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.001, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected cells. (C) Immunoblot analyses for caspase-3, caspase-8, Fas, Fas-L, FADD and PARP in total cell lysates were carried out. The blots were stripped and re-probed with an antibody against the housekeeping gene GAPDH to verify equal loading.

Figure 3. Overexpression of uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibits uPAR and/or MMP-9 downregulation-induced apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells.

4910 and 5310 cells were plated and 24 hrs before siRNA transfection, cells were transfected with cDNA expressing vectors for uPAR (puPAR) and MMP-9 (pMMP-9), alone or together (pUM; co-transfected with puPAR and pMMP-9). After siRNA transfection, cells were incubated for 60 hrs. (A) Immunoblot analyses for caspase-8, Fas, FADD, PARP, uPAR and MMP-9 in total cell lysates were carried out. The blots were stripped and re-probed with an antibody against the housekeeping gene GAPDH to verify equal loading. (B) The TUNEL assay was carried out and the percent of apoptotic cells were quantified. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.05, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected cells.

uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition induced Fas and caspase-8 mediated apoptosis in glioma xenograft cells

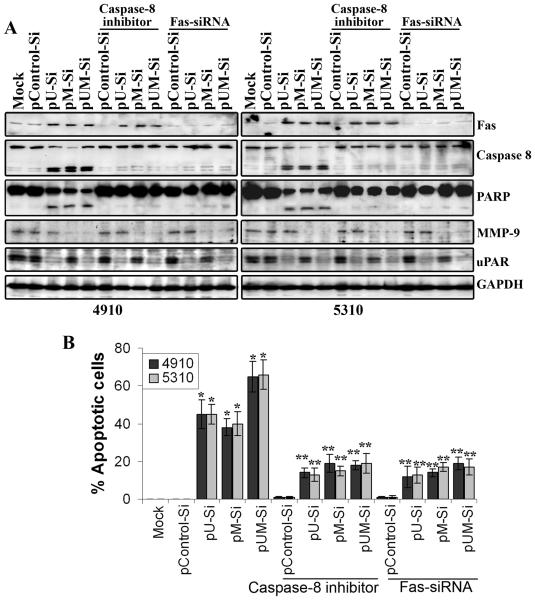

Fas (CD95/APO-1) belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family and triggers an apoptotic signal (25). Immunoblotting revealed that Fas expression was induced in glioma xenograft cells transfected with pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si as compared to mock and pControl-Si-transfected controls, suggesting either uPAR or MMP-9 inhibition induced Fas levels in these cells (Fig 2C). Further, down regulation of Fas using Fas-siRNA in pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si transfected cells prevented the initiation of apoptosis, suggesting that Fas mediated apoptosis in uPAR and MMP-9 inhibited 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells (Figs. 4A-B). We next examined the expression of molecules involved in Fas-mediated apoptosis at a protein level. As shown in figure 2C, glioma cells transfected with uPAR and MMP-9 expressed relatively abundant FADD and cleaved-caspase-8 levels as compared with mock and pControl-Si-transfected controls. To further confirm whether Fas oligomerization can actually induce the activation of caspase-8-mediated apoptosis in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated glioma cells, we evaluated the effect of cell-permeable caspase-8 inhibitor (IETD-fmk) in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated cells. As shown in figures 4A and B, caspase-8 inhibitor inhibited uPAR and/or MMP-9 siRNA induced apoptosis by more than 60%. These results suggest that transcriptional inactivation of uPAR and/or MMP-9 inducing Fas and caspase-8-mediated cell death in uPAR and/or MMP-9 siRNA transfected 4910 and 5310 glioblastoma xenograft cells.

Figure 4. Involvement of Fas and caspase-8 in uPAR and/or MMP-9-siRNA inhibition-induced apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 cells.

36 hrs after siRNA transfection, 4910 and 5310 cells were incubated without or with 50 mM IETD-FMK for 1 hr. (A) Sixty hrs after transfection, cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses using antibodies specific for Fas, caspase-8, PARP, uPAR and MMP-9. The blots were stripped and re-probed with an antibody against the housekeeping gene GAPDH to verify equal loading. (B) Sixty hrs after transfection, cells were analyzed for apoptotic cell population by TUNEL staining. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells were quantified and shown in the graph. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.01, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected cells. **p<0.05, significant difference from various siRNA-transfected cells.

Localization of Fas into lipid rafts modulates the apoptotic pathway in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated cells

Fas-mediated apoptotic signal can be activated independently of the Fas/FasL interaction via the sole redistribution of Fas into the lipid rafts (14, 17). We therefore tested for localization of Fas in lipid rafts in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated glioma cells by immunofluorescence. Immunofluorescence co-staining of GM1, which is a raft marker (26), and a specific anti-Fas antibody revealed localization of Fas in the lipid rafts in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated glioma xenograft cells (Fig. 5A). To further confirm the Fas and raft co-clustering, we isolated lipid rafts from 4910 and 5310 glioblastoma xenograft cells transfected with pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si (Supplementary Fig. 1). Lipid rafts were isolated based on their insolubility in Triton-X-100 lysis buffer at 4°C and fractionated by discontinuous OptiPrep (OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium; Sigma St. Louis, MO) gradient centrifugation as per manufacturer's instructions. GM1-containing lipid rafts, at the upper part (mostly in fractions 2–4) of the OptiPrep gradient (Supplementary Fig. 1A), were identified using CTxB conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (14). The GM1 enriched fractions (lipid raft fractions; 2-4) and non-GM1 enriched fractions (non-lipid raft fractions; 7-9) were pooled separately and analyzed for the known raft and the non-raft marker proteins. Known raft proteins such as caveolin-1, flotillin-1, and flotillin-2 were present in lipid raft fractions and absent in non-lipid raft fractions (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Similarly, non-lipid raft marker, transferrin receptor (CD71/TfR; a non-raft-membrane marker protein) and α-tubulin (a cytoskeletal protein) were only present in the non-lipid raft fractions (27) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Next, we analyzed lipid raft fractions for caspase-8, Fas and FADD by immunoblot analysis. Fas and death receptor downstream signaling molecules FADD and procaspase-8 were in the raft fractions (Fig. 5D). These data show that all the constituents of the key apoptotic complex, DISC, i.e., Fas, FADD and pro-caspase-8, are localized into lipid rafts.

Figure 5. siRNA against uPAR and/or MMP-9 induces co-clustering of membrane rafts and Fas/CD95, and involvement of lipid rafts in uPAR and/or MMP-9-siRNA-induced apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenograft cells.

(A) 4910 and 5310 cells were plated and transfected with mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si or pUM-Si and incubated for 60 hrs. Cells were stained with a specific anti-Fas/CD95 antibody, followed by a Alexa fluor-488- conjugated secondary antibody (green fluorescence), and a Alexa fluor-595-labeled cholera toxin B (CTxB) subunit to identify lipid rafts (red fluorescence). Areas of co-localization between membrane rafts and Fas/CD95 in the merge panels are shown in yellow. The representative images of three independent experiments are shown (Insets: negative control). (B) Thirty-six hrs after siRNA transfection, 4910 and 5310 cells were pretreated with 2.5 mg/mL methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) for 30 min. Sixty hrs after transfection, cells were analyzed for apoptotic cell population by TUNEL staining. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells were quantified and shown in the graph. Columns: mean of triplicate experiments; bars: SE; *p<0.01, significant difference from pControl-Si-transfected cells. **p<0.01, significant difference from respective siRNA-transfected cells. (C) Immunoblot analyses for uPAR, MMP-9, Fas, FADD, caspase-8 and PARP in total cell lysates were carried out. The blots were stripped and re-probed with an antibody against the housekeeping gene GAPDH to verify equal loading. (D) Sixty hrs after siRNA transfection, CTxB-HRP solution was added to cells and were kept on ice for 1 hr. Lipid raft fractions from siRNA-transfected cells were subjected to immunoblot analyses for caspase-8, Fas, Fas-L, FADD, uPAR and MMP-9. The blots were stripped and re-probed with flotillin-1 to verify loading.

We next investigated the role of lipid rafts in apoptosis induced uPAR and MMP-9 inhibited cells. We therefore determined whether the disruption of the lipid rafts would be able to abrogate the apoptotic signal in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated cells. Integrity of the lipid rafts depends on the concentration of cholesterol in the plasma membrane (28), and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), a chelator of cholesterol, dismantles these lipid rafts (14). Treatment with MβCD inhibited uPAR and/or MMP-9 knockdown-induced apoptosis in both 4910 and 5310 cells (Fig. 5B). To further confirm whether lipid raft disruption with MβCD treatment inhibited uPAR and MMP-9 downregulation induced apoptosis in glioma cells, we evaluated expression of Fas and cleavage of caspase-8 and PARP in siRNA and MβCD treated samples by immunoblot analysis. The Fas and Fas L expression was induced in pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si transfected cells irrespective of MβCD treatment (Fig 5C). However, MβCD treatment inhibited uPAR and MMP-9 siRNA induced cleavage of caspase-8 and PARP (Fig. 5C). Further, depletion of cholesterol with MβCD in uPAR or/and MMP-9 downregulated cells did not alter the Fas expression as determined by the immunocytochemical analysis (Supplementary Figure-2). Taken together, these results suggest that localization of Fas in the lipid rafts environment mediates the apoptotic action of pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si in 4910 and 5310 glioblastoma xenograft cells.

Transcriptional inactivation of uPAR/MMP-9 induces apoptosis in 4910 and 5310 glioma xenografts in vivo

To directly evaluate the effect of uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition alone and in combination on tumor formation in vivo, we stereotactically implanted glioma cells intracranially in nude mice. The tumors that arose were challenged with intratumoral injections of pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si by implanting ALZET osmatic mini pumps. Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained tumor sections showed about 55-70% reduction of tumor volume in the brains of mice treated with either pU-Si or pM-Si compared to mock and pControl-Si-treated tumors (p<0.01 vs Mock-treated tumors; Figs. 6A-B). Notably, treatment with pUM-Si regressed tumor growth by more than 85% (p<0.01 vs Mock) compared to mock and pControl-Si treated tumors (Figs. 6A-B). Further, as shown in the Supplementary Figure 3 invasiveness of the tumor cells into normal brain tissue of mice was decreased in these tumor sections.

Figure 6. siRNA against uPAR/MMP-9 inhibits 4910 and 5310 xenograft tumor growth in vivo.

(A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed as per standard protocol and representative pictures of tumor sections from mock, pControl-Si, pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si-treated mice are shown. Tumor portion in sections is shown in dotted yellow circle. (B) Quantification of tumor volume. Tumor volume in pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si-treated animals is normalized with tumor volume in mock-treated animals. Columns: mean tumor volume of six; bars: SE; *p<0.05, significant difference from Mock-treated controls. (C) Immunohistochemistry was carried out for uPAR, MMP-9, Fas and active-caspase-8 using specific antibodies. Also shown is the negative control where the primary antibody was replaced by non-immune serum (insets). (D) TUNEL staining for apoptotic cells indicating cell death in uPAR and/or MMP-9 siRNA-treated mice as compared to mock and pControl-Si-treated mice. (Insets: negative control). Quantification of apoptotic cells in 4910 and 5310 xenograft tumor sections from uPAR and MMP-9 siRNA-treated mice. *p<0.01, significant difference from pControl-Si-treated mice.

To determine whether siRNA against uPAR and MMP-9 caused Fas mediated apoptosis in vivo, tumor sections were immunoassayed for uPAR, MMP-9, Fas and active-caspase-8. Apoptotic content was determined by TUNEL assay. Consistent with our in vitro results, tumor sections from mice treated with the siRNA constructs showed decreased staining for uPAR and MMP-9 compared to pControl-Si treated tumors (Fig. 6C). However, intense staining for Fas and active-caspase-8 was observed from tumor sections of mice that received pU-Si, pM-Si and pUM-Si treatments (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the apoptotic index of tumor cells quantified by the number of positive cells for TUNEL staining showed a moderate increase in the number of apoptosis cells with pU-Si and pM-Si treatments. The number of apoptotic cells was drastically increased in the tumor sections from mice that received pUM-Si treatment (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition induced apoptosis in glioma cells in vitro (19) and suppressed pre-established tumor growth in vivo (23). In the present study, we sought to determine the effect of uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition on two xenograft glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Here, we demonstrate that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition by plasmid-mediated delivery of uPAR (pU-Si) and MMP-9 (pM-Si) siRNA either alone or in combination (pUM-Si) caused programmed cell death in glioma xenograft cells in vitro and in vivo. We also show that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition triggered localization of Fas into lipid rafts leading to the induction of a Fas-mediated apoptotic signal. To our knowledge, this study is the first to link a molecular target of either uPAR or MMP-9 to the previously well-described redistribution of Fas into the lipid rafts and leading to the elimination of glioma cells.

uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition caused apoptosis in glioblastoma in vitro and in vivo as demonstrated by TUNEL staining and caspase-3 activation. Two main pathways: intrinsic and extrinsic pathways leading to caspase activation have been characterized (29). The extrinsic pathway is activated by ligand-bound death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family (30). Fas (CD95/APO-1) belong to the TNF receptor super family and mediate programmed cell death. Here, we demonstrate that the apoptosis-inducing ability of uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition depends on Fas induction. Fas expression was induced in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated glioma xenograft cells. We show that siRNA-mediated downregulation of Fas prevented uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptosis, thereby demonstrating the involvement of Fas in apoptosis. One of the major findings of the present study is that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition leads to high levels of Fas and increases activation of caspases-3 and -8. Previous reports demonstrated that tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) sensitizes the cells for Fas-mediated apoptosis by upregulation and activation of caspases-8 and -3 (31). In the present study, caspase-8 inhibitor decreased apoptosis in uPAR and MMP-9 downregulated glioma cells suggesting that uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptosis is at least due in part to caspase-8 activation. A recent study by Alfano et al underlines the importance of uPAR signaling in prevention of apoptosis by resistance of cancer cells to anoikis (apoptosis induced by loss of anchorage). uPAR expression promotes cell survival by activating anti-apoptosis factor Bcl-xL transcription through the MEK/ERK- and PI3K/Akt-dependent pathways (32). Similarly a compound 5a, an MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor, enhances apoptosis induced by ligands of the TNF receptor superfamily, specifically TNF alpha, TRAIL, and the Fas-crosslinking antibody. Further, they also show that mechanism requires a ligand–receptor interaction and activation of caspase-8 (33).

Previous reports have indicated that cytotoxic drugs induce cell death by triggering Fas clustering in the lipid raft environment (34-37). The mobilization of Fas into the lipid rafts/microdomains has been associated with an increased efficiency of the apoptotic pathway (14, 38, 39). Treatment of glioma cell transfected with uPAR and/or MMP-9 siRNA led to increased aggregation of Fas on the cell surface. Furthermore, Fas was found to be co-localized with lipid raft marker, using Alexa Fluor 555-labeled cholera toxin subunit-B, which possesses a high affinity for the monosialoganglioside GM1 that is concentrated into the microdomains (40).

Formation of lipid raft platforms, where a large amount of signaling molecules are brought together, increases DISC formation and therefore potentiates Fas signaling. The initial events in Fas signaling are largely dependent on the local concentration of the three major components of the DISC-Fas, FADD and caspase-8 and oligomerization of any one component is sufficient to mount an apoptotic response (41). FADD consists of two protein interaction domains: a death domain and a death effector domain that interacts with a death effector domain on pro-caspase-8. Aggregation of initiator caspases at the DISC leads to their autoactivation (42) and they, in turn, activate effector caspases causing the cell to undergo apoptosis. Our studies indicate that both FADD and caspase-8 were localized in the lipid raft fraction. Disruption of the lipid rafts with the methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), a chelator of cholesterol that dismantles these lipid rafts (43), was able to abrogate the uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptotic signal. Further, immunofluorescence experiments indicate that overall Fas levels and Fas recruitment to the cell membrane did not change with MβCD treatment confirming that lipid environment is essential for Fas-mediated apoptosis in uPAR and MMP-9 inhibited cells. The Fas-mediated apoptotic signals can be blocked by dominant negative-FADD, antisense FADD, caspase-8 inhibitors, or by MC159 and E8 (44-48). In the present study, we showed that the caspase-8 specific inhibitor, IETD-FMK, inhibited uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptosis. Taken together, these findings suggest that Fas elicits the apoptotic signal through recruitment of the DED-containing proteins FADD and pro-caspase-8. Co-localization of death receptors and downstream signaling of apoptotic molecules in lipid rafts were previously demonstrated in cancer chemotherapy. These anti-tumor drugs, edelfosine and aplidin, reorganize membrane rafts, promoting their clustering and redistributing their protein content to trigger apoptosis in a Fas-dependent manner (13, 14).

The induction of apoptosis by inhibition of uPAR and MMP-9 in a variety of cancers was also shown previously by other researchers (31, 33, 49, 50) and by us (19, 23, 51-53). These evidences show that downregulation of uPAR and MMP-9, both of which are cell surface proteins, are able to initiate intracellular cell death signaling. However, the mechanisms underlying this regulation of apoptotic signaling are not yet clear and need to be investigated.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrate that uPAR and/or MMP-9 inhibition-induced apoptosis in glioma cells is Fas-dependent and works through localization and co-clustering of Fas into membrane rafts, and the anti-tumor effect relied on the redistribution of Fas into the lipid rafts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Noorjehan Ali for technical assistance, Shellee Abraham for assistance in manuscript preparation, and Diana Meister and Sushma Jasti for review of this paper. We thank Dr. David James, University of California at San Francisco for the gift of 4910 and 5310 cell lines.

This research was supported by N.I.N.D.S Grant NS 047699 (to J.S.R.). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Abbreviations used

- uPAR

urokinase plasminogen activator receptor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- MβCD

methyl beta cyclodextrin

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- CTxB

cholera toxin subunit B

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling

- PARP-1

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- FADD

Fas-associated death domain-containing protein

- GM1

monosialotetrahexosylganglioside

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

Reference List

- 1.Sporn MB. Carcinogenesis and cancer: different perspectives on the same disease. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6215–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao JS. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martel-Pelletier J, Welsch DJ, Pelletier JP. Metalloproteases and inhibitors in arthritic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:805–29. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis: a moving target for therapeutic intervention. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1237–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Gelatinases (MMP-2 and -9) and their natural inhibitors as prognostic indicators in solid cancers. Biochimie. 2005;87:287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Alessio S, Blasi F. The urokinase receptor as an entertainer of signal transduction. Front Biosci. 2009;14:4575–87. doi: 10.2741/3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillay V, Dass CR, Choong PF. The urokinase plasminogen activator receptor as a gene therapy target for cancer. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Yu BW, Rahman KM, Ahmad F, Sarkar FH. Induction of growth arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by 3,3-diindolylmethane is associated with induction and nuclear localization of p27kip. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:341–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos-DeSimone N, Hahn-Dantona E, Sipley J, Nagase H, French DL, Quigley JP. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) via a converging plasmin/stromelysin-1 cascade enhances tumor cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13066–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patra SK. Dissecting lipid raft facilitated cell signaling pathways in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785:182–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster LJ, De Hoog CL, Mann M. Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5813–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peter ME, Krammer PH. The CD95(APO-1/Fas) DISC and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajate C, Del Canto-Janez E, Acuna AU, et al. Intracellular triggering of Fas aggregation and recruitment of apoptotic molecules into Fas-enriched rafts in selective tumor cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:353–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gajate C, Mollinedo F. The antitumor ether lipid ET-18-OCH(3) induces apoptosis through translocation and capping of Fas/CD95 into membrane rafts in human leukemic cells. Blood. 2001;98:3860–3. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grassme H, Cremesti A, Kolesnick R, Gulbins E. Ceramide-mediated clustering is required for CD95-DISC formation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5457–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reis-Sobreiro M, Gajate C, Mollinedo F. Involvement of mitochondria and recruitment of Fas/CD95 signaling in lipid rafts in resveratrol-mediated antimyeloma and antileukemia actions. Oncogene. 2009;28:3221–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheel-Toellner D, Wang K, Singh R, et al. The death-inducing signalling complex is recruited to lipid rafts in Fas-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:876–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peter ME, Krammer PH. Mechanisms of CD95 (APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:545–51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Simultaneous downregulation of uPAR and MMP-9 induces overexpression of the FADD-associated protein RIP and activates caspase 9-mediated apoptosis in gliomas. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:783–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannini C, Sarkaria JN, Saito A, et al. Patient tumor EGFR and PDGFRA gene amplifications retained in an invasive intracranial xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncol. 2005;7:164–76. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chetty C, Bhoopathi P, Joseph P, Chittivelu S, Rao JS, Lakka SS. Adenovirus-mediated siRNA against MMP-2 suppresses tumor growth and lung metastasis in mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2289–99. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kargiotis O, Chetty C, Gogineni V, et al. uPA/uPAR downregulation inhibits radiation-induced migration, invasion and angiogenesis in IOMM-Lee meningioma cells and decreases tumor growth in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:937–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakka SS, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, et al. Specific interference of uPAR and MMP-9 gene expression induced by double-stranded RNA results in decreased invasion, tumor growth and angiogenesis in gliomas. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21882–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chetty C, Bhoopathi P, Lakka SS, Rao JS. MMP-2 siRNA induced Fas/CD95-mediated extrinsic II apoptotic pathway in the A549 lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncogene. 2007;26:7675–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–56. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schon A, Freire E. Thermodynamics of intersubunit interactions in cholera toxin upon binding to the oligosaccharide portion of its cell surface receptor, ganglioside GM1. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5019–24. doi: 10.1021/bi00438a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu H, Wakim B, Li M, Halligan B, Tint GS, Patel SB. Quantifying raft proteins in neonatal mouse brain by ‘tube-gel’ protein digestion label-free shotgun proteomics. Proteome Sci. 2007;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-5-17. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31–9. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–6. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–8. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi T, Okamoto K, Kobata T, Hasunuma T, Sumida T, Nishioka K. Tumor necrosis factor alpha regulation of the FAS-mediated apoptosis-signaling pathway in synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:519–26. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<519::AID-ANR17>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alfano D, Iaccarino I, Stoppelli MP. Urokinase signaling through its receptor protects against anoikis by increasing BCL-xL expression levels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17758–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyormoi O, Mills L, Bar-Eli M. An MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor, 5a, enhances apoptosis induced by ligands of the TNF receptor superfamily in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:558–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aragane Y, Kulms D, Metze D, et al. Ultraviolet light induces apoptosis via direct activation of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) independently of its ligand CD95L. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:171–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett M, Macdonald K, Chan SW, Luzio JP, Simari R, Weissberg P. Cell surface trafficking of Fas: a rapid mechanism of p53-mediated apoptosis. Science. 1998;282:290–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Micheau O, Solary E, Hammann A, manche-Boitrel MT. Fas ligand-independent, FADD-mediated activation of the Fas death pathway by anticancer drugs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7987–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang D, Lahti JM, Grenet J, Kidd VJ. Cycloheximide-induced T-cell death is mediated by a Fas-associated death domain-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7245–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hueber AO, Bernard AM, Herincs Z, Couzinet A, He HT. An essential role for membrane rafts in the initiation of Fas/CD95-triggered cell death in mouse thymocytes. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:190–6. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muppidi JR, Siegel RM. Ligand-independent redistribution of Fas (CD95) into lipid rafts mediates clonotypic T cell death. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:182–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viola A, Schroeder S, Sakakibara Y, Lanzavecchia A. T lymphocyte costimulation mediated by reorganization of membrane microdomains. Science. 1999;283:680–2. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chinnaiyan AM, O'Rourke K, Tewari M, Dixit VM. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1995;81:505–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91:443–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Membrane compartmentation is required for efficient T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;8:723–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beltinger J, Hawkey CJ, Stack WA. TGF-alpha reduces bradykinin-stimulated ion transport and prostaglandin release in human colonic epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C848–C855. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.4.C848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bush JA, Cheung KJ, Jr., Li G. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells through a Fas receptor/caspase-8 pathway independent of p53. Exp Cell Res. 2001;271:305–14. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y, Lai MZ. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation leads to a FADD-dependent but Fas ligand-independent cell death in Jurkat T cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8350–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delmas C, End D, Rochaix P, Favre G, Toulas C, Cohen-Jonathan E. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 reduces hypoxia and matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression in human glioma xenograft. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6062–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo J, Sun Y, Lin H, et al. Activation of JNK by vanadate induces a Fas-associated death domain (FADD)-dependent death of cerebellar granule progenitors in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4542–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besch R, Berking C, Kammerbauer C, Degitz K. Inhibition of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor induces apoptosis in melanoma cells by activation of p53. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:818–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li C, Cao S, Liu Z, Ye X, Chen L, Meng S. RNAi-mediated downregulation of uPAR synergizes with targeting of HER2 through the ERK pathway in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2010 Jan 8; doi: 10.1002/ijc.25159. Epub ahead of print; PMID: 20063318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhoopathi P, Chetty C, Kunigal S, Vanamala SK, Rao JS, Lakka SS. Blockade of tumor growth due to matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition is mediated by sequential activation of beta1-integrin, ERK, and NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1545–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707931200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Kunigal S, Lakka SS, Joseph P, Estes N, Rao JS. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 Inhibition Down-Regulates Radiation-Induced Nuclear Factor-{kappa}B Activity Leading to Apoptosis in Breast Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3617–26. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pulukuri SM, Gondi CS, Lakka SS, et al. RNA Interference-directed Knockdown of Urokinase Plasminogen Activator and Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Inhibits Prostate Cancer Cell Invasion, Survival, and Tumorigenicity in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36529–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.